By David A. Norris

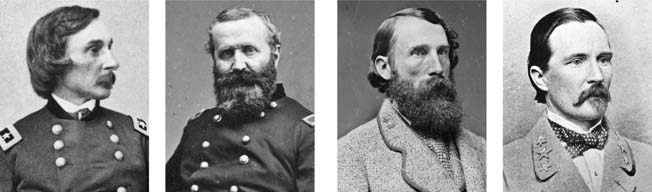

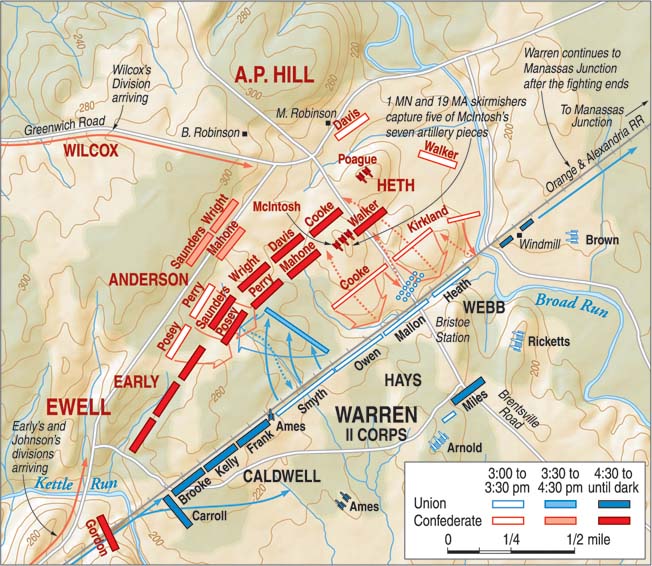

It took only moments for a golden opportunity to turn into a trap. Several days of pursuit in October 1863 through northern Virginia at last brought Lt. Gen. Ambrose Powell Hill within sight of the retreating Union troops of the Army of the Potomac. Without waiting for all of his men to come up, Hill sent two brigades of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s division after the Yankee soldiers retreating across Broad Run. It seemed Heth needed to pause his advance only a few minutes in order to brush aside some skirmishers from his right, but the skirmishers were merely a screen in front of the 8,000 men of Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s II Corps. It looked like Hill’s III Corps of General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia just might crack the Union lines on October 14 in the Battle of Bristoe Station.

An antebellum railroad bed provided the bluecoats with an excellent fortified position, and Warren’s muskets felled hundreds of Heth’s men before they could reach them. Yet there was a weak spot in the Union line where the Brentford Road crossed the Orange and Alexandria Railroad; the flat terrain there offered no cover for the defenders. A charge by Brig. Gen. John R. Cooke’s North Carolinians threatened to break through the 42nd New York.

Lee needed a victory. The three-day Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863 had ended the second Confederate invasion of the North. Withdrawing across the Potomac River into Confederate territory, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was pursued by the victorious Army of the Potomac under Union Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade. Meade followed the Confederate retreat without provoking a major battle. Lee continued giving ground, in the process abandoning Culpeper Courthouse for Meade to take over as his headquarters on September 13. Lee eventually pushed south across the Rapidan River before halting near Orange Courthouse.

The two sides had taken up new positions along the Rapidan line. Lee was operating without Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s 12,000-strong I Corps. With Chattanooga, Tennessee, threatened by Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland, Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered Lee to send Longstreet’s corps to join General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee in northern Georgia. Although Lee objected to the division of his army, Davis told him that the threat to Chattanooga called for drastic measures.

On September 9, the I Corps troops of the Army of Northern Virginia began boarding trains at Orange Court House. Part of Longstreet’s corps reached Bragg in time to help the Confederates win their decisive victory at Chickamauga Creek on September 19-20.

Without Longstreet’s detachment, Lee was down to about 48,000 officers and men. Even with his diminished numbers, Lee kept an eye open for the possibility of a new campaign before the onset of winter. His chance came in late September when Lt. Gen. Joseph Hooker was detached from Meade, taking the XI and XII Corps with him. Like Longstreet’s men, Hooker’s troops were earmarked for the Trans-Appalachian Theater.

Hooker’s transfer left Meade with an army of 78,000. With the odds against him so sharply cut down, Lee planned a new offensive. On October 9, the Confederates left their camps northeast of Orange Courthouse. They crossed the Rapidan and then headed northeast on a course roughly parallel with the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, which was a few miles to their east. “Our progress was slow, as the march was by circuitous and concealed roads, to avoid the observation of the enemy,” wrote Lee. Dividing his cavalry, the Rebel commander left Fitz Lee to hold the old line south of the Rapidan, and sent Lt. Gen. James Ewell Brown Stuart’s cavalry corps to protect the right of the main army.

With Lee on the move, Meade withdrew toward the Rappahannock. His intention was to reach Centreville. Meade was closer to Centreville than the Confederates, and he had the additional advantage of taking the most direct route, which was nearer the path of the Orange and Alexandria. Several miles to their west, Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s II Corps and Hill’s III Corps pushed forward in hope of overtaking Meade before he could settle into stronger defenses at Centreville.

An October 13 attack by Stuart’s cavalry on a Union wagon train ignited the First Battle of Auburn. A tempting prize, the train carried 100 ammunition wagons and 125 ambulances and stretched for two miles along the roads. But Stuart’s scouts had failed to detect two nearby large bodies of Union infantry, the II and III Corps.

Brigadier General John Buford, who led the First Division of Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton’s cavalry corps, escorted the wagons. Late in the day, Stuart realized that his riders were trapped between the wagon train and several thousand foot soldiers. Stuart hid his men in a ravine all night, only a few hundred yards away from some of the camps of Warren’s corps. At 3 am on October 14, Warren’s men broke camp and resumed their march parallel to the railroad, never realizing how close they were to Stuart.

Meanwhile, Ewell’s II Corps and Hill’s III Corps had reached Warrenton, about eight miles west of Auburn, on the night of October 13. Early on the morning of October 14, both corps marched east on different roads with plans to unite at Greenwich. Ewell had a more direct route through Auburn Mills, while Hill’s men marched farther north through New Baltimore and skirted around Buckland Mills.

After a short march, Brig. Gen. John C. Caldwell’s brigade of the II Corps crossed Cedar Run and stopped on a hill overlooking the creek. The Union men fell out, and soon blazing campfires glowed in the half-light across the hilltop as the soldiers waited for their morning coffee to boil. “[It] had not fully dawned and heavy mists in the valley enveloped them in almost impenetrable obscurity,” recalled Warren.

The path assigned to Ewell brought him up behind Caldwell’s troops. While mist cloaked the approaches to the hill, the Yankee campfires threw the bluecoats into high relief for the Rebel artillery. At 6:15 am, the explosions of Confederate shells startled the camp. “The first shell … smashed the hospitable coffee-pot which Father Corby, Dr. Powell [the regiment’s chaplain, and their surgeon] and the writer were filling for breakfast that was rudely interrupted,” recalled a veteran of the 108th New York. A more lethal shellburst killed seven men.

Caldwell’s men abandoned their coffee to find cover on the far edge of the hilltop. Officially, the Second Battle of Auburn, this clash of the morning of October 14, also was known as the Battle of Coffee Hill. Warren’s corps withdrew and pressed on to Catlett’s Station and beyond, heading for Bristoe Station, just beyond which they would cross Broad Run.

Ewell was delayed by the early morning clash at Auburn, and therefore it was Hill who next drew closer to the Yankees. Heth’s division reached Greenwich at 10 am. Captain John A. Sloan of the 27th North Carolina in Cooke’s brigade remembered the exuberant optimism of his men that day. At Greenwich they walked through a deserted Union camp. “Their camp-fires were still burning, many articles of camp equipage were lying around, everything showing that a panic had seized them and that their retreat was hasty and terrified,” wrote Sloan. “We hastened on in pursuit, at a rapid rate, capturing their stragglers at every turn.” Yankee coats, knapsacks, and other gear littered the roads, adding to the impression that the enemy was in headlong retreat. “It was almost like boys chasing a hare,” recalled another North Carolinian.

The II Corps had been, wrote Sergeant John H. Rhodes of Battery B, 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery “almost continually on the march or in line of battle since the morning of the 12th.” Rhodes’ battery was one of the first Union units to reach Bristoe Station.

Thirty miles southwest of Washington, D.C., Bristoe Station sat on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, just southwest of the railroad’s bridge across a creek called Broad Run. Five miles or so to the north were the fields where the First and Second Battles of Manassas were fought in 1861 and 1862, respectively.

Established when the railroad came through in 1850, Bristoe Station served the rural community of Bristow, which was a short distance to the west. (Many wartime sources used the spelling Bristow Station.) During the earlier fighting in the area, much of Bristow was destroyed. Sergeant Rhodes recalled that the village had disappeared and that there were “only a few burnt chimneys remaining.”

Riding with his staff, Hill received reports that he was closing in on the enemy. They scooped up about 150 stragglers and learned that they were on the heels of Maj. Gen. William Henry French’s Union III Corps. Ahead of his troops, Hill paused early in the afternoon on a rise west of Bristoe Station. Below, he saw thousands of Union troops. Most of them were already beyond Broad Run, and safe for the moment.

But the Rebels tiring 15-mile march did not appear to be for nothing after all. It looked like the last of the rear of Meade’s army was still squeezing across the ford at Broad Run near Bristoe Station. Some soldiers marched toward and beyond the stream, while others rested and relaxed on the plain. It presented a golden opportunity to strike and shatter a substantial piece of the Union Army when it was awkwardly sprawled across both sides of the stream. The men of the 27th North Carolina “were in the highest spirits, confident not only of victory, but of destroying or capturing everything in front of us,” wrote Sloan.

Broad Run was no great obstacle. Soldiers could march across the railroad bridge that spanned the creek, or they could easily ford the stream above and below the bridge. Hill decided “that no time be lost, and hurried up Heth’s division, forming it in line of battle along the crest of the hills and parallel to Broad Run.” At the point where the Confederates approached Broad Run, the stream ran roughly north to south before bending to the east below the railroad bridge.

Hill had ridden some distance ahead of his infantry. At every passing moment, he fretted that the enemy was slipping away. Heth was about 11/2miles west of Bristoe Station when orders arrived from Hill. The orders stated that Heth was to arrange three of his brigades “in line of battle perpendicular to the road … holding the Fourth Brigade as a reserve, which was to continue its march by the flank,” Heth wrote in his battle report.

Heth deployed William W. Kirkland’s 1,500 men with their right flank touching the road and brushing against the left of Cooke’s 2,500-man brigade. Henry H. Walker’s brigade, following behind, was ordered to move to Kirkland’s left, and Joseph. R. Davis’s brigade was held in reserve.

Kirkland was still shuffling his troops when a courier dashed up with an urgent message from Hill. Because the Yankees were “retreating rapidly and that expedition was necessary,” Hill instructed Heth to push ahead immediately “with the two brigades then in line.”

When Heth’s soldiers stepped into a cleared stretch of land, they saw the enemy about three quarters of a mile ahead of them. Several guns of Lt. Col. William T. Poague’s battalion perched on a hilltop and opened fire on the Yankees. Heth saw that Poague’s shells “threw them into much confusion, and all that were in sight retreated across Broad Run.”

“On seeing this, General Hill directed me to move by the left flank, cross Broad Run, and attack the fugitives,” wrote Heth. But before Heth could change direction, “a heavy column of the enemy” was spotted to his right. Heth hesitated, and asked for Hill’s instructions. The commander had Heth wait for 10 minutes, then ordered him to resume his advance by the left flank.

Cooke, whose men were closest to the enemy, personally went to Heth. The Yankees, warned Cooke, would assault his right as he moved forward. Hill assured them that Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson’s division was being dispatched to cover Cooke’s right.

The Orange and Alexandria tracks shot as straight as an arrow toward the bridge over Broad Run. The tracks ran atop artificial embankments and, where needed, made cuts through small hills. Between the embankments and cuts, the railroad offered a line of fortifications extensive enough to protect several thousand troops.

Unknown to Heth and Hill, the troops of Warren’s II Corps knew the Confederates were approaching on their left and rushed to occupy the ready-made defenses provided by the railroad bed. Sergeant Milton Ellsworth of the 19th Massachusetts recalled that a bit earlier that day, the regiment crossed Kettle Run, a stream that passed under the railroad just over one mile southeast of Bristoe Station. For the march from Auburn that morning, the 59th New York had been posted as flankers on Warren’s left, but the New Yorkers were pulled back into line after the army crossed the creek. Ellsworth was suspicious because their regiment was still shadowed by soldiers.

Although the unknown flankers were reportedly wearing blue coats, when the matter was reported to Warren, the general sent the 59th New York to confront them. The mystery men opened fire, revealing themselves to be Confederates. The enemy fire was heavy enough to drive the New Yorkers back, and the 19th Massachusetts fell back to the railroad. Finding they were at a stretch where the rails ran over an embankment about three feet high, the bluecoats used it as a breastwork and took cover behind it.

The bluecoat divisions of Brig. Gens. John C. Caldwell, Alexander Hays, and Alexander S. Webb were arrayed from the Union left to the right. Behind them on ground 30 to 40 feet higher in elevation were three batteries with a total of 16 guns. Four guns of Lieutenant Thomas Frederick Brown’s Battery B of the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery also were within range on high ground across Broad Run. Brown’s guns stood near a windmill built before the war to pump water for passing locomotives.

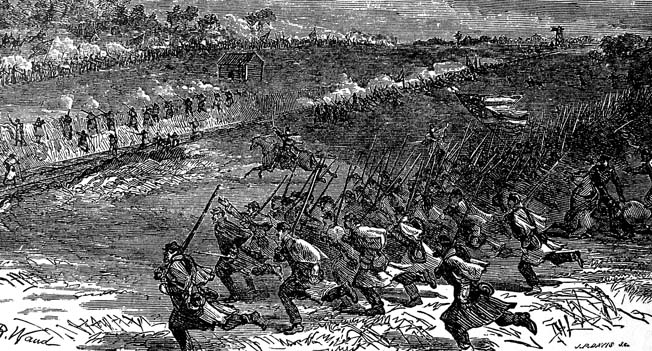

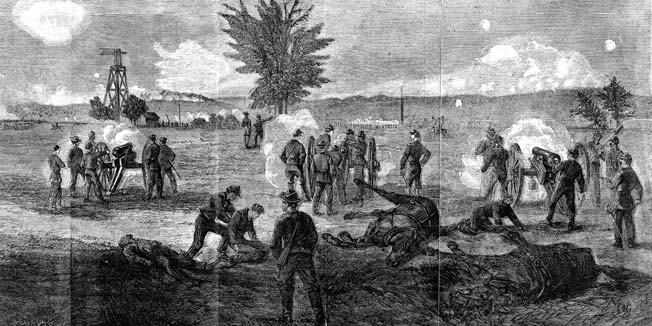

Warren’s men had just settled into their new defensive line when Kirkland and Cooke pressed forward after 2 pm, their combined front roughly parallel with the streambed of Broad Run. But this put the Rebels at an oblique angle to the divisions of Webb and Hays. Cooke was within half a mile of the railroad, and both Rebel brigades were subject to enfilading artillery fire. As the Union skirmishers pulled back, heavy musket fire poured from the railroad cuts and embankments.

The Confederate brigadiers pivoted to maneuver their men into line parallel with the railroad. Once in line, they pushed forward to drive the enemy from its position. The strength of the Yankee line at that point was still unclear to the Rebels. Sergeant Ellsworth wrote afterward of his regimental commander “directing the colors to keep down and out of sight” as the Confederates closed in on them.

“We had scarcely emerged from the woods and began to advance down the hill, when Gen. Cooke … was shot and fell from his horse severely wounded,” wrote Sloan. “Col. Gilmer, in command of our regiment, was shot down about the same moment.”

Command of Cooke’s brigade devolved to Colonel Edward D. Hall of the 46th North Carolina. Lt. Col. George Whitfield took over for Gilmer. Whitfield warned Hall that his regiment must either charge or fall back, rather than remain where they were, trapped in the open. Hall ordered a charge. Without waiting for the rest of the brigade to assemble, Whitfield led his men “double-quicking down the hill, our men falling at every step,” wrote Sloan. “When we came to within a few yards of the railroad, the enemy rose up from behind the embankment and poured a volley into our ranks which almost swept the remnant of us out of existence. At this juncture some of our company sought shelter in a little shanty on our left, where they were afterwards captured by the enemy.”

Across the creek, Brown’s battery had an admirable firing position to rake the charging Confederate infantry. But the Rhode Islanders were isolated from their own infantry, and the gunners were menaced by a small force of Rebel skirmishers.

A bugler named John F. Leach managed to corral 13 Union stragglers partly by brandishing his saber. Mounted on a battery horse, Leach took charge of his hastily assembled force. As if he were an officer, the bugler rode up and down his little line of infantry. Three of his men combined their fire to kill a Confederate sniper who was shooting at them from a tree. Leach was later trapped under his horse when his mount was shot down. While dragging himself back to his feet, the bugler was injured when an enemy shell exploded and slashed his right leg with an iron fragment. Yet the motley band of stragglers held, leaving Brown’s guns free to bombard Kirkland’s men. After his injuries were patched up, Leach survived the battle and the war.

Cooke’s men pushed to within 40 yards of the railroad. The 19th Massachusetts “lay quietly, having the greatest confidence in our ability to take care of them, until they came very near to us, when we arose and emptied our guns in their faces and cheered and charged over the road,” wrote Ellsworth.

Three color bearers of the 27th North Carolina were shot down in only a few minutes. Corporal William C. Story picked up the banner and held it for the rest of the battle. Lt. Col. Whitfield was shot, and command of the 27th fell to Major Joseph C. Webb, who ordered the regiment to withdraw. The remaining men pulled back to take cover behind the crest of a hill.

Some of Cooke’s troops reached the point where the Brentsville Road crossed the rail bed. That section of the Union line was held by the 42nd New York, known as the Tammany Regiment,” of Colonel James E. Mallon’s brigade. The New Yorkers occupied a vulnerable spot in the Union line, a stretch where the rail bed transitioned from cut to embankment, leaving a piece of level ground with no premade defenses.

The Tammany Regiment’s losses at Antietam and Gettysburg had been made up with conscripts who found themselves in their first battle. Part of their line, manned by these new conscripts, wavered until Mallon steadied them. Starting the war as a private, Mallon rose quickly in rank. He was commissioned a colonel of the 42nd New York on March 17, 1863. Mallon and most of the regiment were Irish American, and so they appreciated their new colonel taking command on St. Patrick’s Day.

Mallon rallied the regiment along the Brentsville Road. He then ordered a charge that drove back the Rebels and restored the line. During the fierce fighting Mallon fell mortally wounded when a bullet struck him in the stomach. His men carried him a short distance behind the lines where surgeons and assistants had found a ditch deep enough to provide some shelter while they gave emergency aid to the wounded. Behind them, Union guns on the crest of a hill lobbed shells over their heads toward the Confederates. Mallon lingered there for half an hour until he died, becoming the highest ranking Union officer killed at Bristoe Station.

On the Confederate left, Kirkland was struck by a bullet that smashed into his left forearm. About 1,000 yards northeast of the spot where Mallon fell by the Brentsville Road, some of Kirkland’s troops broke through the Union defenses and poured down the steep slope of the railway cut. The 11th North Carolina, on the extreme left of the Rebel battle line, had the most success. Followed by some of the 52nd North Carolina, the Confederates found themselves in the approximately 100-yard gap that separated Webb’s right flank from the Broad Run railroad bridge. The 82nd New York of Colonel Francis E. Heath’s brigade, which anchored Webb’s right, lost seven men killed and 19 wounded. The 82nd had the distinction of suffering the highest number of men killed in any of the Union regiments that fought that day.

To the left of the 82nd New York was the 15th Massachusetts, also of Heath’s brigade. So far, the Massachusetts regiment had fought the battle while divided into two ranks. The soldiers in the front rank lay on their left sides, firing over the iron rail, while the rear rank reloaded and passed up their muskets. Approximately 20 Rebels made it far enough down the tracks to lay down flanking fire into the 15th Massachusetts. The regiment suffered two killed and nine wounded during the battle. Most of the casualties occurred during the moments that Kirkland’s charge hit its peak.

Once in the sights of Union muskets ahead of and beside them, Kirkland’s troops also were raked by Brown’s Rhode Island guns just across the stream. Shells lobbed by other Union batteries posted behind Webb and Hays burst among them. Command of the 11th North Carolina fell to a captain, the highest ranking officer still on his feet. Several hundred of Kirkland’s brigade surrendered rather than be shot down scrambling out of the railroad cut into an open field swept by muskets and artillery. Webb reported that the Confederates who attacked his division lost 300 prisoners and two battle flags. Many of the captives were rounded up while taking shelter in some old huts in an abandoned camp built during one of the previous campaigns fought in the area.

Although the Confederates were close to breaking through parts of the Yankee formations, their bold charge was in vain. Hill had sent them ahead while failing to provide reinforcements to exploit their temporary success and decisively break Warren’s II Corps. Both of Heth’s embattled and unsupported brigades reeled back, leaving behind hundreds of casualties.

On the Rebel left, Walker’s men were pulled back from across Broad Run, but it was too late. By the time Walker was in place, the attack had already collapsed.

As the Rebel onslaught lost steam and rolled backward, Cooke’s men flowed past a detachment of Major David G. McIntosh’s artillery battalion. When ordering Heth’s brigades forward, Hill had sent McIntosh’s guns to cover them from a rise overlooking the battlefield. Hill had failed to get word to the brigade commanders, though, and Colonel Hall had been unaware of the need to protect the guns. “Our losses both by casualties and straggling shortened our line so much that … the left of the brigade was some distance to the right of the guns,” wrote Hall.

McIntosh, however, wrote of the retreating infantry “falling back through the guns.” The major said that he tried to rally the foot soldiers, but he was unable to stop any of them. One of the artillery officers, Lieutenant William T. Wilson, was knocked down and wounded by a shell.

Stranded without support, the Confederate guns kept up their fire. Aside from a round or two of canister thrown at the enemy foot soldiers, they concentrated on the more distant enemy artillery. A courier set out to notify Hill that McIntosh’s guns were in peril, and their position was untenable. Hill never received the message.

Leaving seven guns in action, McIntosh left for a short time to find a new firing position for two of his guns. One of the guns met with an accident. Feeling it unwise to open fire with a single gun, the major returned to the other guns. Upon his return to the battalion, he found that his other seven guns had fallen silent. Lieutenant Samuel Wallace reported that he no longer had enough men able to work the pieces. Later reports counted three gunners dead and two officers and three dozen men wounded at Bristoe Station. Forty-four of the battery’s horses were disabled in the action. The major ordered his men, who had taken cover in the bush, to drag the guns away by hand.

As the men prepared to haul away their pieces, enemy soldiers appeared over the crest of a hill in their front. They were skirmishers from the 1st Minnesota and the 19th Massachusetts of Webb’s division. The skirmishers swarmed over five of the Rebel guns. His gunners outnumbered, McIntosh ordered his men to withdraw, pulling away their caissons and limbers as quietly as possible. Colonel Hall and General Walker dispatched soldiers to protect McIntosh’s guns, but by the time they arrived, the Yankees had rolled their prizes away.

Sergeant Daniel Corrigan of the 19th Massachusetts set out on foot to take the enemy guns, but he rode back in triumph. Two companies of the regiment were thrown out in front as skirmishers after their regiment helped make prisoners of many of Cooke’s men. The wary lieutenant in charge of the skirmish line kept most of his men close at hand, but he allowed Corrigan and two other men to man the guns. Corrigan “limbered up one of those taken by the Nineteenth, mounted the saddle leader and drove it in triumph down the field and over the railroad track with a bump into the lines, amid a shower of balls from the enemy and a storm of cheers from his comrades,” recalled a fellow soldier.

On the Confederate left, Anderson sent forward the brigades of Brig. Gens. Carnot Posey and Edward A. Perry. They also found Warren’s infantry comfortably protected by the railroad. The two guns placed by the railroad further protected the Union infantry. Federal skirmishers tried to cut into the gap between Anderson’s left and Heth’s right, but Posey and Perry pushed them back. The clash on this part of the field was brief, but Posey fell with a mortal wound. Some Confederate guns were dragged into position and traded shots with the Union artillery, but night soon fell and the firing ended.

Behind the tracks, Warren’s men waited. About 9 pm, a staff officer brought new orders to the 19th Massachusetts. The II Corps was withdrawing beyond Broad Run. The staff officer relayed instructions that “no word of command was to be given above a whisper, and each man was to keep his hand on his canteen and dipper to keep them from rattling.” Striking matches was forbidden, and smokers could only dream of their pipes or cigars. As the Yankees slipped away into the night, Rebel campfires flared only a few hundred yards away. Occasionally the retreating Yankees heard scraps of Confederate fireside conversations, or the despairing groans of wounded men still lying between the lines. After daybreak on October 15, Meade’s troops settled into their old campsites and earthworks around Centreville.

There was no triumph in the Confederates holding the ground where they had fought hours before. Captain Sloan wrote that after dusk soldiers “with litters and canteens of water, repaired to the battlefield to take care of the wounded.” Hill’s troops were poised to continue the fighting when the sun rose again. But the morning sun shone upon no enemy troops, just the empty defenses along the railroad that the Yankees had abandoned in the dark hours before.

Bristoe Station was a brief battle with heavy losses for the South. The Confederates had about twice as many troops on hand at Bristoe Station as the Union, which was atypical for a Civil War battle. But Hill had deployed only a fraction of his forces, leaving two brigades to bear the full brunt of the resistance against three Union divisions.

Confederate losses were nearly three times those of the Northern forces. Heth reported 143 killed, 773 wounded, and 445 missing, for a total of 1,361. Cooke lost approximately 700 men and Kirkland slightly more than 600. Heaviest hit was Cooke’s 27th North Carolina, which suffered 290 men and 33 officers killed, wounded, or captured. Each of the two Confederate brigades that attacked the Yankees along the railroad lost more men than Warren’s entire corps. Because of the shelter offered by the embankments and cuts, Union losses amounted to only 540 casualties.

Anderson’s division, barely involved in the action, had only 54 casualties. But Posey had been killed, and Cooke and Kirkland were both severely wounded. The two wounded generals would not return to action for months.

Hill expressed ambivalence about his management of the battle. “I am convinced that I made the attack too hastily, and at the same time that a delay of half an hour, and there would have been no enemy to attack,” he wrote in his battle report. “In that event I should have equally blamed myself for not attacking at once.”

Heth defended the performance of his troops. “No military man who has examined the ground, or who understands the position and the disproportionate number of contending forces, would attach blame to these two brigades for meeting a repulse,” wrote Heth. “Had they succeeded in driving the enemy in their front before them … it is probable that the two brigades would have been captured by the enemy unengaged on their right.”

Many of the Confederate officers and soldiers who fought at Bristoe Station felt a deep sense of betrayal at the way the battle was managed at the top. “A worse-managed affair than this fight at Bristoe Station did not take place during the war,” wrote Captain John A. Sloan, summarizing the feelings of many of the survivors. “With the rest of our corps in the rear, at a moment’s call, Cooke’s and Kirkland’s North Carolina brigades were made to fight this battle alone.”

A dreary rain fell on the battlefield as Lee looked over the scene of the disaster with Hill on the following day. The Army of Northern Virginia could ill afford the losses incurred for no appreciable gain. “Bury these poor men and let us say no more about it,” Lee told Hill.

Three days after Bristoe Station, Lee wrote Confederate President Jefferson Davis that Meade “is now reported to be fortifying at Centreville.” Attacking the fortifications would be costly, and turning Meade’s flank would simply drive him to safety in the vast tangle of defenses surrounding Washington, D.C. Feeding the army from the countryside around Centreville was impossible for any length of time because the region had been picked clean from continual campaigning. The Yankees had burned the railroad bridge over the Rappahannock, thereby rendering the Orange and Alexandria useless to the Rebels. Thus, Lee returned to the Rappahannock.

At Lincoln’s urging, Meade opened a final operation in late 1863. Pushing south across the Rapidan River, Meade sought to bring battle to Lee’s army. But, the Confederates fortified a strong defensive position behind a stream called Mine Run. On the morning of November 30, Warren observed the well-placed Confederate lines. Knowing an attack would be repelled at a horrendous cost, Warren cancelled the assault, which could well have been a mirror image of Bristoe Station. Meade concurred, and the Union troops withdrew to go into winter quarters above the Rappahannock, ending the active campaigning of the fateful year of 1863 in the Eastern Theater.

The Union offensive that began in the spring of 1864 marked a new phase of the war in Virginia. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who became commander of all Union armies in March of that year, would accompany the Army of the Potomac in the field. Although the cautious Meade would remain the army’s commander, he would be under Grant’s direction. Unlike the slow maneuvering and minor clashes of the fall 1863 campaigns, the fighting of 1864 would open with the Battle of the Wilderness; thereafter, Grant’s aggressive tactics would keep the armies clashing nearly every day until the collapse of the Army of Northern Virginia, and the Confederacy itself, in April 1865.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments