By Ludwig Dyck

On Christmas morning, 800 ad, a tall, powerfully built man walked up the steps of Saint Peter’s basilica in Rome. Highly pious but by no means meek, Charles, ruler of the Frankish empire, had come—so he thought—simply to attend mass. In his mid-fifties, Charles retained the characteristic vigor for which he was known, his muscles hardened by years of warfare and his two favorite pastimes, hunting and swimming. He usually preferred the blue cloak and cross-gartered leggings of his own people, but today he had obliged Pope Leo III, who had personally asked him to wear a long tunic, Greek mantle, and shoes of Roman fashion. In his classical garb, Charles stood out among the locals like a visiting deity, which in a sense he was. His fair skin, golden hair, piercing blue eyes, and great height marked him as a man of the cold, gloomy northern realms.

If Charles had had any inkling of the elaborate ceremony about to take place, he likely would have avoided the entire affair. He was a no-nonsense sort of individual, a man more accustomed to giving orders than to taking them. But as a scrupulously practicing Catholic, he felt it his duty to obey a summons from the pope, even one who had a good deal more reason to obey Charles than the Frankish king had to obey him. In a spirit of faithful cooperation, Charles had agreed to attend mass wearing the fulsome costume of a classical hero.

“The Most Pious Augustus”

Once inside the church, Charles was surprised and somewhat taken aback by the emotional greeting accorded him by the pope. Leo, having barely escaped imprisonment and mutilation by his political enemies on spurious charges of perjury and adultery, owed his recent reinstatement to Charles, who had publicly shown his support of the pope and demanded that he be restored to his seat as bishop of Rome. Now the grateful Leo returned the favor by placing a golden crown on the king’s startled head while the entire congregation cried out a blessing: “To Charles, the most pious Augustus, crowned by God, mighty and pacific emperor, life and victory!” After 324 years, there was once again an emperor in the West—not that Charles, better known to history as Charlemagne, needed a papal decree to make him emperor. He had already been one in fact, if not in name, for many years.

Through Charles’ great heart pumped the blood of the Franks, one of the major Germanic tribal groups. Centuries earlier the Franks poured into Roman Gaul from their homelands on the lower Rhine. The Western Roman Empire was in its death throws and the great migrations were in full swing. Axe wielding Frank infantry, mailed Goth cavalry and fearsome Hun archers, among a colorful array of tribes, carved up the carcass of the Western Empire. The final act came in 476 AD, when a barbarian general disposed the last of the West Roman Emperors. Through sheer force and deceit, King Clovis (c.465-511) consolidated the Franks’ hold on Northern Gaul and spread their suzerainty over much of Europe. Born a pagan, Clovis’ shrewd mind saw the Catholic Orthodox Church as a potential ally and unifying force. Clovis allowed himself to be baptized, along with thousands of his troops.

Hedonistic Excesses

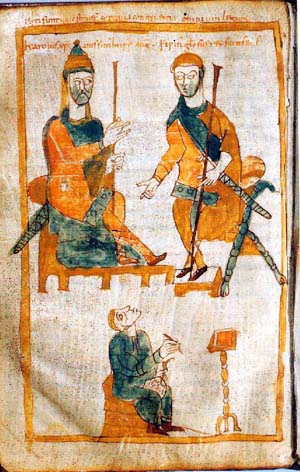

Hedonistic excesses inevitably sapped the vigor of Clovis’s dynasty, the long-haired Merovingians. Their power gradually gravitated into the hands of their leading officials, the Arnulfing, or as they later became known, the Carolingians. The most famous of these usurpers was Charles Martel—the Hammer—who in 732 repulsed a Moorish invasion of Europe at the Battle of Tours and henceforth was immortalized as a savior of Christendom. Martel’s grandson, eight-year-old Charles, must have looked up to his grandfather with awe. Born out of wedlock, Charles was the oldest of three children born to Pepin III, known by the unflattering nickname Pepin the Short. While his father was disposing of the last of the Merovingian kings in 751, Charles was learning from grizzled veterans how to use the weapons of war—the spear, the round shield with its heavy iron boss, the single-edged short sword, and the most powerful weapon of all, the double-edged long sword. It was a skill that would stand him in good stead in years to come.

The western Europe of Charles’s youth was fragmented by tribal rivalries, the growing power of the Catholic Church, the encroachment of Islam, and the waning influence of the Byzantine Empire. All these factions jockeyed for advantage and territory. When a tear-stained Pope Stephen II threw himself at Pepin’s feet in 754 and begged for his aid against the “most evil Lombards,” he was hoping that Pepin would help the Church retain its tenuous hold on Rome and the rest of Italy. At the time, the most prominent power in Italy was Lombard King Aistulf, who had just swallowed up the last Byzantine lands around Ravenna and was threatening to do the same to Rome, swearing that “the Romans would all be butchered unless they submit themselves to his dominions.”

Honoring the Franks’ Ancient Alliance

Fortunately for the Church, Pepin decided to honor the Franks’ ancient alliance, which went back to the days of Clovis. Pepin not only wrested the Byzantine lands away from the Lombards but, instead of handing them back to their rightful owner, the Byzantine emperor, he gave them to the Church instead. In gratitude, the pope anointed Pepin and his sons, Charles and his younger brother Carloman, as his rightful heirs. Besides the Lombards, Pepin also fought Saxon and Moorish raiders. More often than not, Charles was at his father’s side. After a lengthy campaign, the kingdom of Septimania on the Spanish border was conquered and subdued in 759, after which time its renowned Goth cavalry became a loyal ally. The rebel kingdom of Aquitaine, however, gave Pepin more trouble. During the eight-year-long Aquitaine War, Pepin’s Bavarian vassal, Duke Tassilo, refused to send any help, thus beginning a long feud between him and the Carolingians. Pepin, preoccupied by the fighting in Aquitaine, was unable to resolve the feud and bring Tassilo back into line.

When Pepin died in 768 at the age of 54, his kingdom was divided in Frankish tradition between his two sons. From the start, the two brothers did not get along. Egged on by court flatterers, Carloman resented having to share his father’s lands with a “bastard”—Pepin had not yet married their mother, Berta, when Charles was born—and refused to help his brother in Aquitaine. Like his father, Charles was left to fight alone. Nevertheless, Charles drove the rebel leader into Gascony, whose duke not only surrendered the fugitive, but also submitted his province to Charles. Carloman was infuriated by his brother’s success.

In 770, Charles married the second of his five wives, Desiderata, daughter of Lombard King Desiderius. Engineered by Charles’s mother, it was an effort to smooth out the traditional enmity between Lombards and Franks, but it failed miserably. The pope, fearing a diminution of his own power, was outraged, cursing the union of the Frankish people with the “perfidious and foully stinking race of the Lombards.” Charles was none too happy himself. Claiming that Desiderata was ill and barren, he sent her back to her insulted father within the year. Relations with the Lombards soured further when Carloman suddenly fell ill and died. When Charles annexed Carloman’s kingdom, Desiderius sheltered the anti-Charles nobles of Carloman’s court, along with Carloman’s wife, Gerberga, and his infant sons. Together, Gerberga and Desiderius hatched various plots to check Charles’s growing power.

In 772, Desiderius made another grab for the Papal States, attempting to bully the pope into declaring that Carloman’s son, not the bastard Charles, was the true ruler of the Franks. Charles strove to resolve the situation without resorting to violence, offering Desiderius 14,000 solidi in compensation for the Papal lands. Desiderius foolishly interpreted Charles’s goodwill as a sign of weakness and refused the offer. Although it was late in the year and the weather had turned foul and cold, Charles believed there was no time to be lost. In a two-pronged attack, his Frankish warriors descended upon Italy. Charles led one column down the shoulder of Mont Cenis, while his uncle, Count Bernard, moved through the St. Bernard pass, thereafter named after the count’s patron saint.

Cold wind, rain, and sleet whipped at the Franks, who drew their cloaks about them and lifted one weary leg after another. The slowly moving columns, burdened by pack horses, leather-covered ox carts, and a wide array of herdsmen, cooks, carpenters, and merchants, pushed steadily onward. When Charles’s column descended into the valley of Susa, the hardest part of the trek was behind it. The soldiers may have breathed a sigh of relief, but they soon saw to their dismay the powerful Lombard fortifications that stretched across the valley ahead. Prince Adelghis, son of Desiderius, had come to contest Charles’s entry into Italy. Undaunted, Charles ordered an immediate assault.

With brawny arms lifting banners and battle horns resounding with a thunderous bellow, the Franks fell upon the Lombard parapets and towers. Lombard bows twanged and arrows thudded into shields and faces. Lombard swords hacked through shoulder bones, blood poured through rent mail, and spears thrust and parried as the Franks tried vainly to scale the ramparts. Charles was contemplating a retreat when, according to legend, a wandering minstrel happened by. The ministrel sang of a secret mountain pass that led to the rear of the Lombard lines: “What reward shall be given to the man who shall safely conduct Charles into Italy?” the singer wondered, “on paths where no spear will be hurled, nor shield raised against him?”

Whatever the truth of the legend, Charles did send a detachment along a high trail, which ever afterward was known as “the Way of the Franks.” The next morning, at dawn, he renewed his frontal assault. Suddenly, the Lombards heard the tramp of marching feet, the clatter of arms, and the neighing of horses—not just in front of them but behind as well. Outflanked, the Lombard army broke in panic, while Frankish cavalry rode down the stragglers. Soon, Prince Adelghis had had enough. He fled to Verona and from there eventually made his way to the safety of the Byzantine court.

Unlike his son, Desiderius was not yet ready to give up yet. He abandoned Susa and rallied his troops for a last stand at Pavia. Meanwhile, Charles reunited with Bernard’s column and advanced unopposed on the Lombard capital. In fanciful prose the Monk of Saint Gall, one of Charles’s biographers, captured the scene. Watching from a high tower, Desiderius was awed by the size of the Frankish army and the sight of Charles himself: “From the west a mighty gale, the wind of the true north [blew], which turned the bright daylight into frightful gloom,” the monk wrote. Charles “rode ever on, topped with his iron helm, his fists in iron gloves, his iron chest and his Platonic shoulders clad in iron cuirass. He raised an iron spear high against the sky. [I]n his other hand his unconquered sword.”

Like Charles, his personal warriors, the “scara,” sported chain mail armor, iron coifs, and helmets. A scara’s full arms and horse were of enormous expense, costing 40 solidi—as much as a dozen cows. Only the king, his lords, and bishops could afford such splendidly equipped warriors. The military value of mail was such that any merchant exporting mail shirts was forced to forfeit his property. The bulk of the soldiers made due with a spear, a bow, and a shield, all provided by their home villages. Charles’s entire armed forces numbered an estimated 30,000 heavily cavalry and 120,000 local levies. Most of these troops were absorbed in garrison duty; the field army rarely numbered above 35,000. Charles counted on his scara to breach Pavia’s defenses, but once again the Lombards held the Franks at bay.

Lacking powerful siege equipment, Charles had to settle for a lengthy investment. A siege camp, including a chapel, sprang up beneath Pavia’s mighty walls, graced by the arrival of Charles’s new young queen, Hildegaard. Before winter passed, Charles found time to visit Rome, where he was given a triumphant reception. Roman soldiers lined the Flamian way, children waved palms and olive branches and sang hymns of praise to the puissant savior of the Church. Meanwhile, disease and famine did much of Charles’s dirty work for him, wearing down Pavia’s defenders. In June 774 the city fell and Charles seized the Iron Crown of the Lombards for himself. Desiderius was exiled to a monastery.

Even this was not the end of the Desiderius feud. One of his daughters, Liutberga, wife of Tassilo, goaded her husband to move against Charles. Not that Tassilo need any prodding—what he needed were powerful allies. He looked to Italy, where half the Lombard lands still remained in the hands of their dukes. There was no questioning the loyalty of Eric, Duke of Friuli, nor that of Hildebrand, Duke of Spoleto, but Arichis, Duke of Beneveto, was another matter. Arichis eagerly allied himself with Tassilo, and the two were further strengthened by an alliance with Constantine VI, the Byzantine boy-emperor who was still fuming because he had been denied Charles’s daughter in marriage.

Charles crushed the brewing conspiracy before it could get out of hand. In 787, flexing his military muscle sufficed to intimidate Beneveto into submission. To spare the people the ravages of war, Charles accepted Arichis’s overtures of peace and made Arichis’s son Grimoald duke in his stead. The following year, Grimoald seemingly proved his loyalty by fighting with Duke Hildebrand against Byzantine invaders from Sicily. In years to come, however, Grimoald would prove to be an unruly vassal. In Bavaria, meanwhile, Tassilo contemptuously refused to acknowledge Charles’s suzerainty until he was confronted by a massive three-pronged assault. Then, like his father-in-law Desiderius, Tassilo meekly surrendered and was shipped off to a distant monastery.

Before his fall, Tassilo had unwisely opened a new Pandora’s box by inviting the much-feared Avars across his borders. From their homelands in Turkestan, the Avar warlords had migrated west to settle in the old Roman province of Pannonia (now Hungary), subjugating the local Slavs. Under their “Kagan,” the great Khan, they had rapidly become a menace to their Slav, German, and Byzantine neighbors. For years, even the Byzantine emperor was forced to pay them an annual tribute of an astounding 80,000 gold solidi. Five years earliler, swarthy Avar chieftains with brightly colored strands interwoven into their hair had visited Charles’s Royal and Military Assembly in Saxony. They talked of peace, but Charles considered them little better than wolves and worried that, if given the chance, they would sink their teeth into his growing empire.

In 788, with new insurrections brewing among Charles’s Bavarian and Italian vassals, the Avars saw their chance. They unsuccessfully attacked Friuli, then advanced into Bavaria. Again they were defeated and their terror-stricken warriors chased into the Danube River to drown. After so many defeats, the Avars reconsidered the wisdom of trying to challenge the mighty king of the Franks. In 790 their envoys came to Charles’s palace at Aachen to negotiate a mutually acceptable border with Francia along the River Enns. It was too late—the time for talk had passed.

At the assembly, enthusiastic cheers greeted Charles’s proposal to take the war to the Avars. On the banks of the Enns, Charles held mass for three days, imploring God’s help for the welfare of the army and victory over the Avars. Near Vienna, Avar pickets beheld the ominous sight of Charles’s great army approaching on both banks, with a flotilla of warships sailing between them. Whether or not God was really on Charles’s side that day, the Avars decided to abandon their defenses without a fight. At the same time, Frankish cavalry led by Charles’s son, the 14-year-old Pepin, struck the Lombards in Italy. A prideful Charles wrote to his wife, “Our beloved son tells us that the Lord God gave them overwhelming triumph: so great a number of men have never been killed in battle.” Victory seemed assured when disaster struck. Pestilence broke out among the horses, devastating the cavalry, and alarming news arrived of a palace revolution instigated by Charles’s neglected bastard son, Pepin the Hunchback.

Charles immediately returned home to squash the revolt, and for several years he was kept busy by the Saxons and other affairs. In 795, reports of dissension among the Avars surfaced when the emissaries of the highest Avar “tundun,” or chancellor, appeared at Charles’s court. The emissaries declared that the tundun wished to submit himself and his people to the Christian faith. The Avars had indeed turned upon each other, and in the ensuing civil war Duke Eric of Friuli, sensing easy prey, unleashed his Lombards under a Slav general named Wonimir. On the plains of Pannonia, armored Lombard and Avar horsemen sliced through each other’s ranks. The more disciplined Lombards completely shattered the Avars’ ring, a series of fortified earthworks surrounding Pannonia. Duke Eric faithfully sent the vast Avar treasures back to Charles.

That same year the tundun and his followers were baptized as Christians, but soon broke their fealty. A second Frankish army under Pepin was needed to hold the ring and secure the rest of the treasure. In all, 15 wagons loaded high with gold and silver coins rolled into the court at Aachen. A gratified Charles lavished gifts on his friends and allies and used the wealth to complete his magnificent palace and chapel. After three more years of sporadic fighting, the Avars and their lands were fully incorporated into Charles’s empire.

Even more savage than the Avar war was the one against the Saxons. By the end of the great migrations, the Saxons occupied most of northern Germany. Unlike most of the other Germanic peoples, they had never embraced Christianity and stayed true to their old gods of nature. The Saxons were the most poorly equipped of Charles’s many foes. Cavalry and armor were all but unheard of—a spear, an axe or, if he was lucky, a sword was all a Saxon soldier could count on. What the Saxons lacked in equipment, however, they made up for in brutality. A terrible cycle of raids, counterraids, murder, robbery, and arson was the order of the day along the Saxon-Frank border.

In 772, fuming with anger, a vengeful Charles crossed the Rivers Eder and Diemel. Deep in the Saxon heartland, at Eresburg, he destroyed the sacred, all-sustaining pillar of the Saxons, the wooden Irminsul. There had been sacrificed to Othin eight different beasts and one man, hung from branches, their blood soaking the earth at the Saxon holy site. There, too, were treasures of gold and silver to enrich the Frankish war chest. The Irminsul’s destruction only served to unite the Saxons under a powerful guerilla leader, Widukind, whose vengeful warriors set fire to Frankish villages and churches, looting, raping, and killing at will. Everywhere, Frankish villagers fled in terror before the grim Saxon army. As soon as Charles’s heavily armed troopers arrived, Widukind’s raiders took to the woods or melted into the general population.

Unable to come to grips with the partisans, Charles released his Franks on the hapless Saxon villages. He had come to stay, and his men set to work building new strongholds or capturing old ones. The Saxons struck back, infiltrating a Frankish camp in 775 and butchering the sleeping garrison. The following year the Saxon army demolished the Frankish stronghold at Eresburg, but faltered at Syburg, which resisted both the clumsily built Saxons siege engines and the torch. By 777, the Frankish banner fluttered over many of the circular palisades, ramparts, and moats that protected the strongholds of Saxony.

Widukind had fled to his kinsman, the pagan king of Denmark, but returned to lead another uprising in 778. The following year the Franks tore through the Saxon ramparts at Bochult. In the aftermath of the battle, churchmen in lavish robes moved among dead and dying, aiding the few doctors, chanting psalms, and giving last rites. The clergy also became a permanent fixture of the Saxon wars, as Charles further consolidated his hold on the land by establishing mission districts.

In 782, news arrived of Slavic raiders on eastern Saxon borders. Charles sent three high-ranking commanders—Adalgis, Geilo, and Worad—to take care of the intruders. The three marched their soldiers east, where to their horror their Saxon auxiliaries deserted in another massive uprising led by the elusive Widukind. When Charles heard this, he sent in reinforcements under his cousin, Count Theodoric. The Saxons awaited the four Frank commanders on the slopes of Süntel Mountain. Theodoric ordered a pincer movement, much to the annoyance of the other three commanders. Confident that they did not need Theodoric’s help, Adalgis, Geilo, and Worad attacked prematurely. With a blare of trumpets they spurred their cavalry up the slope, right into the Saxon lines bristling with spears. It was a slaughter. The Saxon ranks stood unbroken, the Frank cavalry a writhing mess of dying and trampled horses and men. Both Adalgis and Geilo, along with five counts and 19 other nobles, perished in the attack.

A raging Charles came storming back across the Rhine, but once again the Saxon army vanished into the villages and forests, while Widukind found safety among the Danes. Charles’s fury knew no bounds. In a grisly bloodbath at Verden, some 4,500 Saxons were rounded up and beheaded. And if that alone did not prove his point, Charles had churches built near his Saxon military outposts and ordered the death penalty for any Saxon who refused baptism or committed even the slightest transgression against Christianity.

The next few years saw incessant raids, battles, and assaults on castles as Charles pushed through Saxony and into the lands of the Slavs. Those Slavs who readily submitted to Frankish dominion he treated as allies. The others were subject to the same brutalities he had shown the rebellious Saxons. In 785 Widukind, after two more defeats, at Detmold and at Osnabrück, finally surrendered. He had had enough bloodshed and accepted that the Christian god was stronger than Othin. Widukind was baptized at Attigny. As a sign of respect for his old adversary, Charles stood as Widukind’s godfather. With Widukind gone, peace seemed assured until 793, when the annihilation of Count Theodoric and his entourage by a Saxon ambush reopened the war.

Charles’s final answer was forced deportations—7,000 Saxons in 794, every third household and 1,600 leaders in 798. This finally did the trick, as increasing numbers of Saxons remained loyal and the centers of resistance shrank to the eastern borders of their realm. In 804, when 10,000 Saxons—their entire population east of the Elbe—settled in Francia, the last embers of resistance flickered out. Christianity had been hammered into the Saxons through 30 years of war. They learned their lessons well. Centuries later their descendants, the Teutonic Knights, marched east to convert the pagan Baltic peoples at the point of the sword.

Charles fought longer in Saxony than anywhere else, but it was in Spain that he fought arguably his most famous battle, which was, ironically, also his greatest defeat. During the 777 Assembly at Paderborn, a deputation of exotic strangers caused much attention among the tall, fair-skinned Franks and Saxons. Suleiman ibn Al-Arabi, the governor of Barcelona and Gerona, had come to ask Charles’s help against his rival, the Emir Abd al Rahman of Cordova. Suleiman was ready to hand over his own cities to the Frankish leader and promised that the governor of the key strategic city of Saragossa would do so as well. Charles liked what he heard, and in 778, over 40,000 Franks and allied Lombards, Bavarians, Burgundians, Provençals, Bretons, and Goths crossed the Pyrenees to meet at Saragossa’s gates. The enraged Muslims inside the city refused to open the gates to the infidels. For a month Charles laid siege to Saragossa. Although Suleiman kept his word and submitted both Barcelona and Gerona to Charles, he was unable to offer any concrete help. Branded as a traitor to the Muslim cause, Suleiman was assassinated by an emissary of Abd al Rahman. Frustrated, Charles called off the siege and headed home. On the way he vented his anger on the less fortified city of Pamplona, razing the walls and sacking the city.

Disaster befell the Frankish column on its way through the narrow pass of Roncesvalles. Hidden in the woods and shrubs lurked thousands of wild hill folk, the Basques. They patiently watched as the Franks marched through the forbidding countryside. After a long wait, the column’s rear guard and baggage trains came into view. The day was hot and the Frank soldiers huffed in their heavy mail and wiped rivulets of sweat from their brows. Suddenly, with a low rumble, boulders began bouncing down the slope toward them, crushing whoever was caught in their wake. Storms of arrows whistled through the air, piercing shields and flesh. With a roar, the lightly armed Basques swept down the slope. A furious chaotic melee erupted. Overwhelmed, the Franks fought to the last man. Among the fallen was Roland, prefect of the Breton march. Darkness shrouded the crimson, corpse-filled pass. The Basques looted the baggage and quickly disappeared into the night. Although a humiliation for Charles, the episode was later immortalized in the famous “Song of Roland.” In the song, the Basques are changed to Saracens and Roland becomes the brave hero who blows his horn, a desperate call for help, too late to be saved.

The turn of the century marked the end of Charles’s great conquests. Battles continued to rage on virtually every border of his realm, but they were for the most part wars of consolidation. Brittany rebelled repeatedly and was never really conquered. In the east, the withering of the Avar and Saxon wars gave way to escalating conflicts with the Slavs. Led by Charles’s namesake son, the Franks conquered the Serbs and Bohemians. In Italy, Charles’s second son, Pepin, king of Italy, was kept busy with the unfaithful Grimoald of Beneveto. Ortona and Lucera were besieged, and there were skirmishes with the Byzantines over control of Venice.

With old age creeping upon him, Charles left most of the fighting to his sons. He remained behind at Aachen, enjoying its hot springs and busying himself with the administration of his empire. The latest and most dangerous threat to his power was the advent of the Vikings. From Norway, the sons of Odin hit the British Isles the earliest and the hardest. The Danes under King Godofrid made war on Charles’s Slavic allies and raised a colossal rampart along the Danish-Saxon border from the Baltic to the North Sea. In 810, Godofrid’s huge fleet of 200 ships crushed the Frisians, who were part of the Saxon kingdom. Godofrid boasted that he could not wait to meet Charles in open battle. Never one to ignore a direct challenge, Charles mounted his battle charger for the last time. Even at the uncommonly old age of 70, the king was still an imposing figure. Before the two forces could clash in combat, Godofrid was murdered by one of his retainers. His fleet returned home and his successor hastily made peace with Charles. In the future, there would be much war between the Vikings and the Franks, but not while Charles still lived.

In carving out the first pan-European empire, Charles had not refrained from using overt violence to obtain his goals, but within his realm there existed a state of peace unknown in the West since the days of the Pax Romana. Charles ruled with a firm but steady hand, keeping his soldiers on a tight leash and forbidding widespread pillaging and drunkenness. Whenever possible, scouts marked out the routes of Charles’s military campaigns, warning villagers of approaching battles and even advising them of the exact number of cattle and sheep that would be requisitioned when the army passed through. Instead of sowing destruction, Charles fostered the liberal arts by building monasteries, schools, and a great bridge across the Rhine. At his court in Aachen the intellectual elite of Europe gathered in what became known as the Carolingian Renaissance.

Charlemagne’s ascendancy was not lost on the rest of the Western world. There was ongoing correspondence with the various kings of the British Isles and the Byzantines. Harun-al Rachid, the opulent Caliph of Baghdad and enemy of the Spanish Emirate of Cordova, became Charles’s lifelong friend. One of his gifts to the great barbarian king of the north was an elephant named Abbul Abuz.

In 823, Charles personally crowned his remaining legitimate son, Louis the Pious, King of Aquitaine, as his co-emperor and successor. Originally, Charles had intended to split his empire in traditional Frankish fashion among his three sons, but both Pepin and Charles the Younger had died prematurely. Unfortunately for the Franks, Louis had inherited his father’s love for learning but not his warlike nature. When, on January 28, 814, Charles succumbed to old age after 47 years as king of the Franks, Louis found himself unequal to the task of carrying on his father’s legacy. It was not long before blood feuds and political infighting fragmented the empire. The days of empire were over, anyway. The medieval age had begun. Still, Charles the Great—Charlemagne—long would be remembered as the ideal king, the champion of Christ, the father of Europe, and the inexhaustible source of glorious legends.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments