By Thomas Haymes

On the evening of Saturday November 22, Lieutenant Robert Crisp of the 4th Armored Brigade came upon the airfield at Sidi Rezegh. He describes what he saw as he crested the southern escarpment overlooking the airfield:

“Straight ahead and below, in the middle distance, lay the square, clean pattern of a desert airfield, its boundaries marked by neat lines of wrecked German and Italian fighter planes, its center littered with shattered tanks from some of which the smoke was rising black into the blue sky.

“On my left the desert stretched away covered with thin-skinned vehicles, but strangely empty of human movement. On my right, and between our two tanks and landing ground, the slope and bottom of the escarpment was crawling with the limp dark figures of men digging slit trenches, putting down mines, clustered around anti-tank and field guns or, unbelievably, cooking a meal. On the other side of the depression the opposite escarpment was full of men, less active than those below, and every now and again I saw a flash of gunfire.

“Neither Tom [the other Honey commander] nor I could tell whether any of the men, vehicles or guns were enemy or friendly. The only positive identification we had were the tanks on the airfield … all the burning ones were British Crusaders.”

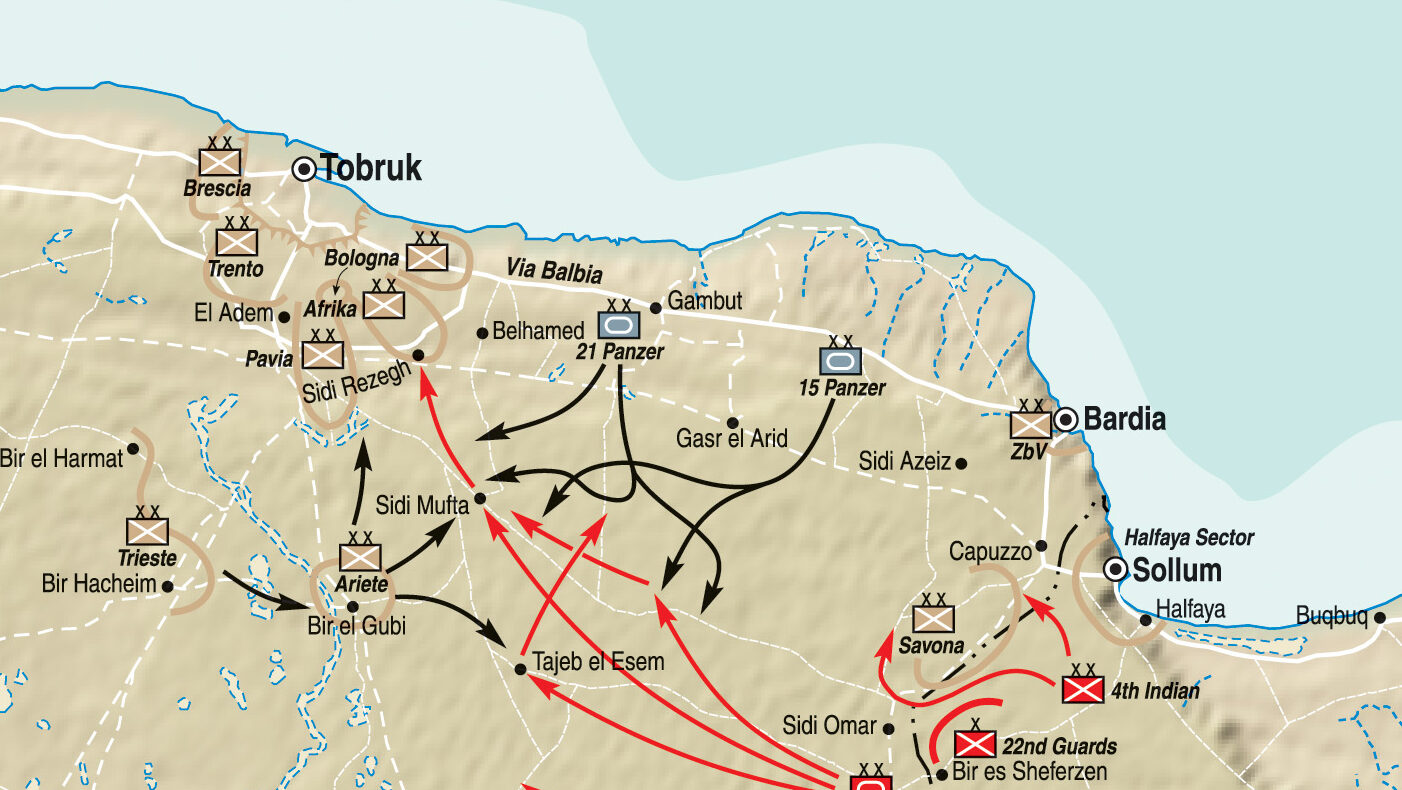

The men that Lieutenant Crisp saw on the bottom of the escarpment were the remnants of the 7th Support Group and 7th Armored Brigade while the troops on the far escarpment were members of the German Afrika Division.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments