By Arnold Blumberg

Scouts for the U.S. Third Army on foot and in armored vehicles cautiously approached the town of Luneville on the east side of the Moselle River in the rolling hills of north- eastern France on September 15, 1944. As the lead M8 armored car of C Troop, 42nd Cavalry Squadron reached the outskirts of the fog-shrouded town, a shell fired from a German 88mm gun slammed into it. The startled Americans quickly fled the area.

Although no one knew it at the time, the shot heralded the beginning of the Battle of Arracourt, an 11-day armored fight between U.S. Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army and German General of Panzer Troops Hasso von Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army.

Over the next four days, the 4th Armored Division of Maj. Gen. Manton Eddy’s XII Corps fought against Generalleutnant Eberhard Rodt’s 15th Panzergrenadier Division for control of Luneville. On September 16, the Americans vigorously attacked the town from the south, fiercely opposed by panzergrenadiers who had been reinforced a day earlier by six tanks and an equal number of antitank guns. The Germans were forced from the town, and the Americans formed a defensive cordon around the city.

On September 17, the Germans made a concerted effort to reclaim Luneville. Their efforts were thwarted by the cavalry troops and tanks and armored infantry from Combat Command R, U.S. 4th Armored Division. The fight for the town heated up on September 18 as two battle groups from Colonel Heinrich von Bronsart-Schellendorf’s 111th Panzer Brigade, supported by units from Generalleutnant Edgar Feuchtinger’s 21st Panzer Division, attacked Luneville from the southeast. At the same time, Colonel Erich von Seckendorf’s 113th Panzer Brigade struck the Americans from the northeast. By 12 PM, reinforcements from Combat Command A, 4th Armored Division in the form of Task Force Hunter, which comprised a company of tanks, infantry, and tank destroyers, arrived and drove the Germans from Luneville and the surrounding area. However, fighting for the town continued on September 19 when the 15th Panzergrenadier Division returned to cover the withdrawal of German forces from the town.

In the struggle for control of Luneville, 1,070 Germans were either killed or captured and 13 armored fighting vehicles were destroyed. American losses amounted to several hundred GIs dead and wounded, and the loss of approximately 10 armored fighting vehicles. With Luneville secured, Patton’s Third Army planned to use the entire 4th Armored Division as its spearhead in a rapid advance toward the German frontier.

At U.S. Third Army headquarters, the American reaction to the German attack at Luneville in mid-September was one of little concern. The enemy effort was so weak and disjointed that the Americans believed it was merely a poorly coordinated local counterattack. Although Third Army intelligence knew of the presence of the 111th Panzer Brigade in the area, it did not know of the 113th Panzer Brigade’s whereabouts, nor did it have any hard evidence that a large enemy armored attack was planned for the immediate future.

Activated in April 1941, the 4th Armored deployed to France in July 1944 and was com- manded by Maj. Gen. John S. Wood. The division’s main fighting units were three brigade-sized formations known as Combat Command A, B, and R (which stood for reserve). Each was orga- nized around a single tank battalion composed of 53 Sherman M4 medium tanks and 17 Stuart M5A1 light tanks, an armored infantry battalion of three companies totaling 1,000 men transported on M2 and M3 armored half-tracks, and an armored field artillery battalion with 18 self-propelled 105mm guns. The 4th Armored Division was augmented by the independent 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion. This unit controlled three companies with a total of 36 M18 Hellcat tank destroyers. A divisional reconnaissance squadron composed of four troops in 48 M8 armored cars gave the American armored divisions a solid scouting asset, which by 1944 was better than the much-diminished reconnaissance battalions attached to German panzer and panzergrenadier divisions.

Although the Americans were unaware of it, the 4th Armored Division’s intended advance over the next 11 days would be disrupted and blocked by a German armored counterattack that was second only to the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944 as the largest armored contest between U.S. and German Armies in the European Theater of Operations. The Lorraine armored battles proved to be classic meeting engagements where both sides were simultaneously conducting offensive maneuvers with neither side possessing any significant numerical or distinct defensive advantage. The U.S. Third Army commanders did not realize, as the third week of September began, that the fight for Luneville put up by the Germans occurred because that was where the German offensive in the Lorraine was supposed to be launched.

The prolonged armored battle in Lorraine followed the collapse of Wehrmacht resistance in France and Belgium and the resultant swift advance of the Western coalition forces across the breadth of France following Patton’s breakout from the Normandy bridgehead on July 30. While the overall Allied pursuit of the German Army toward the western margin of the Reich was most impressive, the Supreme High Command of the German Army (Oberkommando des Heeres, or OKH) was most concerned about the lighting speed of Patton’s Third Army.

Despite crippling fuel shortages that periodically retarded its progress, the Third Army managed to drive 400 miles from Normandy to the west bank of the Moselle River. The enemy forces defending Lorraine along the Moselle line belonged to General of Panzer Troops Otto von Knobelsdorff’s First Army, which comprised six infantry and three panzergrenadier divisions. For the most part, these divisions had been replenished with underequipped and poorly trained replacements. First Army possessed fewer than 200 armored fighting vehicles of all types. The Luftwaffe units supporting the First Army had only 110 aircraft.

While operating in Lorraine, Patton’s Third Arm was composed of Eddy’s XII Corps, Maj. Gen. Walton Walker’s XX Corps, and Maj. Gen. Wade Haislip’s XV Corps. The Third Army brought to the Arracourt fight eight well-equipped divisions, including three armored and four attached tank battalions. The Third Army had 933 tanks, of which 672 were M4 Sherman medium tanks and 261 were M5A1 Stuart light tanks. In addition, the U.S. Army Air Corps backed up Third Army with 400 fighters and fighter bombers from its XIX Tactical Air Command.

In compliance with the wishes of the Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Patton was directed to liberate Lorraine and then breach the Siegfried Line defenses guarding Germany’s western frontier. Once those daunting objectives were achieved, Third Army was to cross the Rhine River and capture the cities of Frankfurt and Mannheim. This fatal stab into Germany would ensure the Allied capture of the Saar Region, which furnished coal and steel for the Hitler’s war machine.

Patton ordered his 4th Armored Division toward the German border on September 19. In

accordance with that plan, the division’s CCB was to push on from the Delme-Chateau-Salins area, 16 miles north of Luneville, to the city of Saabrucken, while CCA was to advance from its location at Arracourt, which was situated 10 miles north of Luneville, and capture the German city of Saareguemines.

To deal with the threat posed by Patton’s Third Army, Hitler ordered Manteuffel to launch a bold counterattack. Manteuffel had proven his skill at handling panzer forces on the Eastern Front where he commanded the 7th Panzer Division of Army Group Center during its advance toward Moscow in 1941. Man- teuffel’s attack, which had a tentative start date of September 5, was to originate west of the Vosges Mountains and drive across the Langres Plateau toward the Moselle River. However, this proved impossible since Fifth Panzer Army’s headquarters was not able to redeploy from the northern sector of the front in the Netherlands to Strasbourg until September 9.

Moreover, Manteuffel had the enormous task of assembling his three panzer and three panzer grenadier brigades from a variety of different regions. This was a complex task given that some of them were deployed on the front lines. Because of Patton’s swift advance, the German attack ultimately was pushed back to September 15.

Frustrated by the series of delays, Hitler ordered the offensive to begin regardless of whether all of the allotted forces had arrived at the staging area. Fully realizing the unrealistic time table for the attack and the inadequate forces to be committed to it, Manteuffel was deeply skeptical that his attack would succeed. With so few battle-worthy panzer divisions in the Lorraine sector of the Western Front, the German attack on the U.S. Third Army would have to depend on the new panzer brigades that had been formed in the late summer of 1944. Nearly all of the Third Reich’s tank production during that time had been diverted to equip the new armored formations. Many of the new panzer brigades were slated for service on the Eastern Front. Indeed, Hitler had established the panzer brigade program in an effort to keep pace with the Soviet Union’s robust tank pro- duction. However, the concept of these new panzer formations on which Hitler placed such great hope was deeply flawed.

Rather than a balanced combined arms unit, such as that fielded by the German Army’s panzer divisions deployed at the outset of World War II, the new panzer brigades contained mostly tanks and panzergrenadiers. They sorely lacked sufficient artillery, engineer, and logistical assets. Designed for quick counterattacks, they were ill suited for sustained periods of frontline combat.

The first of these brigades were numbered 101 to 110. They actually were similar to a reg- iment in strength and had only one tank bat- talion. Their armor included 36 PzKpfw Panther medium tanks and 11 Pz IV/70 tank destroyers. These brigades’ infantry component consisted of 2,100 panzergrenadiers in six companies transported in SdKfz 251 half-tracks that mounted 20mm cannons.

In response to the shortcomings of the first series of panzer brigades, a second series desig- nated 111 to 119 was fielded in August 1944. These contained two battalions of tanks, one of which had 36 Pz.Kpfw V Panthers and the other of which had 36 Pz.Kpfw IVs. The infantry complement was expanded to a regi- ment of two panzergrenadier battalions of three companies each, as well as a heavy weapons company. In addition, each brigade had one armored reconnaissance company, assault gun company, and engineer company. Due to the shortage of SdKfz half-tracks, most of the 4,800 troops in these brigades had to travel in trucks, which severely limited the cross-country capability of the brigade.

Manteuffel, tasked with using Panzer Brigades 106, 111, 112, and 113 in the attack against

Patton’s forces in Lorraine, was particularly concerned about the combat reliability of these units. He had little confidence in their fighting ability due to the absence of any artillery in the brigades, a lack of radio equipment for communications, and insufficient armored recovery and maintenance services. He also pointed out that the men in the new panzer brigades had not been trained in combined- arms tactics.

Lieutenant General Walter Kruger, who led LVIII Panzer Corps, was deeply critical of the battle worthiness of the new panzer brigades. “Panzer Brigades 111 and 113 … were makeshift organizations,” he wrote. “Their combat value was slight. Their training was just as incomplete as their equipment. They had been given no training as a unit and they had not become accustomed to coordinating their subunits.” His disgust for the caliber of troops sent to the front from rear-echelon formations was evident in his description of them as “barrel-scrapings.” The concerns of the senior panzer leaders involved in the forthcoming mission about the usefulness of the panzer brigades to be employed did not bode well for its success.

Knobelsdorff was so alarmed in early September by the approach of Patton’s Third Army to the Moselle River that he wanted to launch an immediate spoiling attack against Walker’s XX Corps before it could cross the river. Knobelsdorff intended to send Colonel Franz Bake’s 106th Panzer Brigade against Maj. Gen. Raymond McClain’s 90th Division on the extreme left flank of Third Army. But before he could send the 106th Panzer Brigade into action, Knobelsdorff had to promise Hitler that he would return it to First Army’s reserve within 48 hours.

The 106th Panzer Brigade, which was organized in two groups, moved under cover of dark- ness on the night of Sept. 7-8 toward the American flank. With the arrival of darkness, the attack groups split up at Audun-le-Roman. The first attack group drove northeast toward Landres, and the second attack group turned southeast toward Trieux.

Having failed to reconnoiter the enemy’s position, at 2 AM the first attack group rumbled past McClain’s headquarters, which was situated on a wooded hill south of Landres. Curious as to the nature of the traffic, a member of the crew of a Sherman tank guarding the headquarters realized after an hour that it was a German column. He alerted nearby artillery crews. The Americans knocked out a half-track, but one of the German Panthers blew up the Sherman. A number of American artillerymen were killed in the sharp firefight. The first attack group disengaged and continued south.

McClain immediately issued orders to his infantry battalions to engage the Germans. The U.S. 712th Tank Battalion started up its Shermans and they caught up with the back of the first attack group column and fired on it. Meanwhile, U.S. bazooka teams from a tank destroyer platoon prepared to engage the Germans at first light.

Much to the consternation of the Germans, the Americans stood their ground rather than retreating. A battle unfolded at dawn when the first attack group split up to attack the town of Mairy from two directions. The town was vigorously defended by the 1st Battalion, 58th Infantry, which had 3-inch antitank guns. Additionally, the Americans were supported by 105mm howitzers. The panzer grenadiers attacked into the town on halftracks, but they could not dislodge the Americans.

After nearly three hours of hard fighting, the Germans began to disengage. One half of the attack group was able to retire, but the other half was targeted by the U.S. artillery where it was positioned in a sunken road west of Mairy and completely destroyed.

The second attack group pushed west from Trieux toward Avril, but the Americans were at Avril in force. They used their antitank guns to repulse a half-hearted attack by the Germans probing their positions. The defeat of the 106th Panzer Brigade in the Battle of Mairy left it badly crippled and of limited use during the forthcoming Battle of Arracourt.

Four days later, elements of Brig. Gen. Holmes E. Dager’s CCB, 4th Armored Division and infantry from the 35th Infantry Division crossed the Moselle south of the railroad hub of Nancy. The following day, September 13, Combat Command Langlade, named after its commander French Colonel Paul Girot de Langlade, part of Haislip’s XV Corps, foiled a spoiling attack at Dompaire by Panzer Brigade 112.

After its defeat at Dompaire, the 112th Panzer Brigade was in no shape to engage in combat for the time being. In addition, the 107th and 108th Panzer Brigades were withdrawn from Lorraine and placed in reserve to help defend the German city of Aachen against an imminent attack by the U.S. First Army. These events would seriously weaken the offensive Hitler had envisioned to serve as a hammer blow to Patton’s Third Army.

Not only were the forces marked to participate in Manteuffel’s main attack altered, but the scheme itself was changed just before it was to be launched. With Patton’s tanks in control of Luneville and the German forces assembled northeast of the town, Manteuffel aimed his assault against the American southern flank toward the town of Arracourt, which lay 10 miles north of Luneville. Hitler’s ambitious panzer attack of mid-September had devolved from its ambitious objectives of striking Patton in the flank, cutting his lines of communication, and destroying him to the much lesser goal of eliminating the spearhead of the U.S. Third Army.

On September 14, the foot soldiers of the 80th Infantry Division of the XII Corps spilled over the river to the north of the city. That same day, 4th Armored Division’s CCA, led by Colonel Bruce Clarke, reached the east bank of the Moselle just below Nancy. Eddy asked Clarke if he felt it was safe to cross his CCA to the east bank. Clarke passed along the query to Lt. Col. Creighton W. Abrams, who commanded the 37th Tank Battalion attached to CCA. “That is the shortest way home,” said Abrams, pointing to the east bank.

Clarke approved the order and Abrams’ tank battalion crossed the river. Once across it continued its lightning advance and by nightfall had driven 20 miles into the German rear. The American advance beyond the Moselle threatened to create a breach between the German First Army and General of Infantry Friedrich Wiese’s Nineteenth Army to its south. This would enable Patton’s tanks to race across the German border and into the Saar Basin. OKH realized that the unrelenting pressure from Patton would require an immediate and vigorous counterstrike against his army.

By mid-September 1944, Wood’s 4th Armored Division had a complement of 163 tanks supporting its 15,000 troops. The well-trained division, which had only been in combat since late July, had been fortunate not to have sustained heavy casualties. The 4th Armored Division had encountered few German tanks since it broke out of Normandy and sped across France. This was because it had not faced determined German panzer units until it reached Lorraine. As a result, the 4th Armored’s troops had no real experience facing German tanks.

On September 19, Manteuffel finally unleashed the armored offensive in Lorraine that Hitler had been demanding since late August. The morning of the attack dawned as it had the last several days with intermittent rain and thick fog in the low-lying areas. The terrain around Arracourt was agricultural, with gently rolling hills and tracts of woods. While the hills were not particularly high, some of them offered good vantage points for surveying the surrounding farmland. These vantage points would play an important role in the coming fight.

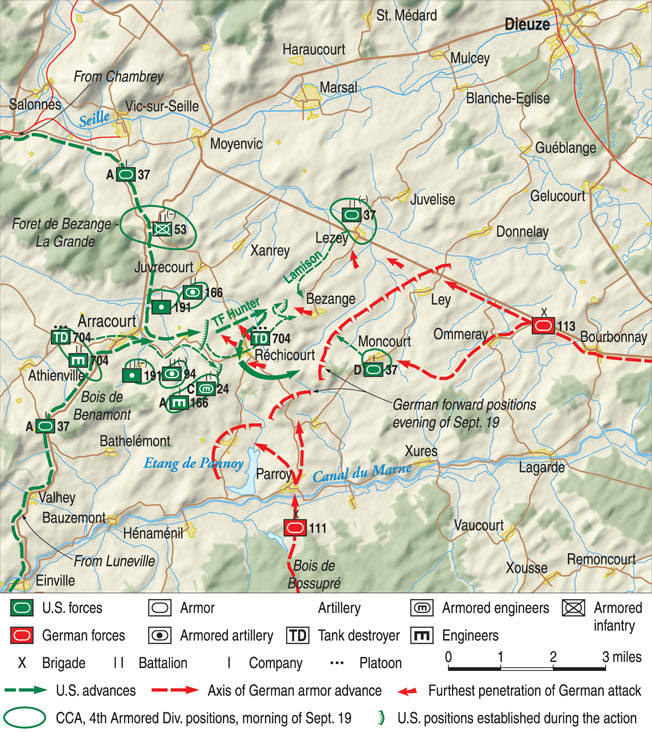

Fifth Panzer Army’s strike on September 19 took the form of two simultaneous thrusts. One thrust consisted of the 113rd Panzer Brigade advancing northwest from the town of Bourdonnay along the Metz-Strasbourg road toward Lezey-Moyenvic. The other thrust involved the 111th Panzer Brigade striking the Third Army’s center by way of the Parroy-Arracourt axis.

The objective of the operation was to link-up with Colonel Enrich von Loesch’s 553rd Volks- grenadier Infantry Division north of Nancy at Chateau-Salins, thus closing the breach the Americans had previously opened between the German First Army and the Nineteenth Army to its south. Barring the Germans’ way was Clarke’s CCA, which had deployed in 4th Armor’s southern sector around Arracourt. The division’s northern zone near Chateau-Salins was covered by CCB.

When the German tanks began to roll on the morning of September 19, CCA’s main components were the 25th Cavalry Squadron, 37th Tank Battalion, and the 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion. CCA was understrength since Task Force Hunter, amounting to one third of the combat command’s strength, had been detailed the day before to aid the fight for Luneville. Clarke’s command post was at the Riouville farm a half mile east of Arracourt. Guarding the command post was a platoon of Hellcats, two battalions of M7 105mm self-propelled howitzers, and a battalion of tractor-drawn 155mm artillery pieces.

CCA’s left flank was shielded by B Company, 37th Tank Battalion and C Company, 10th Armored Infantry Battalion. This small task force linked CCA with CCB to its west. CCA’s center consisted of the balance of the 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion, which was deployed on the southeast ridge of the Bezange Forest overlooking Moyenvic. The right margin of the combat command consisted of the unit’s headquarters company and C Company, 37th Tank Battalion, which held the village of Lezey. At the village of Moncourt, on the eastern por- tion of CCA’s zone, stood a platoon of Stuart tanks belonging to D Company, 37th Tank Battalion. Screening CCA’s front was a line of out- posts manned by the troopers of the 25th Cavalry Squadron. Near the center of CCA’s position was the 166th Engineer Battalion.

The first contact CCA had with the enemy near Arracourt occurred at 7 AM when fire from a Stuart light tank destroyed a German half- track near Moncourt. Shortly afterward, five Panther tanks emerged from the fog and forced D Company to retreat to the main 37th Tank Battalion assembly area near the hamlet of Bezange-la-Petite. The Americans spotted another column of German armor moving along the Metz-Strasbourg road.

Notified of the enemy’s advance, Colonel Clarke ordered Captain William Dwight, 37th Tank Battalion’s liaison officer, to take a platoon of tank destroyers and establish a blocking position on Hill 246 approximately 800 yards from the village of Rechicourt-la-Petite. It was 7:45 AM when Dwight, with four M18 Tank destroyers under Lieutenant Edwin Leiper, reached the summit of Hill 246. No sooner had the crews assumed firing positions than they saw a single Ger- man tank emerge from the woods at the base of the hill.

The lead tank destroyer, commanded by Sergeant Stacey, opened fire, striking the enemy tank with its first shot. More German tanks were seen, and Stacey destroyed a second target in quick succession. A third German tank hit Stacey’s Hellcat, which caused injuries to the crew, but it was able to move under its own power back to Arracourt. Another Hellcat destroyed the Pz IV that had disabled Stacey’s gun. Two more German tanks were knocked out as they tried to reverse into the wood.

As the German armor withdrew, so did Leiper’s three remaining M18s, which rumbled onto a neighboring height. Leiper noticed a string of German tanks on a road running along the hills between Rechicourt and Bezange-la-Petite. The Americans unleashed a fusillade of armor-piercing shells at the new target. To make sure the tanks were completely destroyed, they called in an artillery strike from nearby M7 105mm guns. The torrent of American artillery shells destroyed five Pz IV tanks.

The fog and occasional rain had thus far prevented American airpower from coming into play; however, some help from the sky was forthcoming. Major Charles “Bazooka Charlie” Carpen- ter, the head of the 4th Armored Division’s reconnaissance aircraft detachment, was flying in the area. He dove in his L-4H single-engine reconnaissance airplane on German tanks trying to work their way around Leiper’s position. Although he was unable to hit the tanks with his 2.36-inch rockets, he alerted Leiper to the threat to his rear.

Reacting to the German threat, Leiper pulled one of his vehicles around and hit two German tanks. But a third German tank destroyed two Hellcats in quick succession. Leiper withdrew toward Arracourt with his remaining Hellcat. As he did, he was joined by three Sherman tanks sent by Abrams. While mopping up an enemy infantry platoon, one was hit by a panzergrenadier armed with a panzerfaust.

As Leiper battled south of Arracourt that morn- ing, farther north C Company, 37th Tank Battalion, commanded by Captain Kenneth Lamison, engaged German armor along the Metz-Strasbourg road. In the initial contact, Lamison and his fellow tankers disabled three Panthers that emerged from the thick fog. Recoiling from that loss, the Germans withdrew south of the highway.

Lamison hurriedly sent a platoon of Shermans to a commanding ridge near Bezange-la-Petite to trap the retreating foe. The American tankers sprung the ambush. From a flanking position, they knocked out four enemy tanks. Then, the Shermans hid on a reverse slope before their opponent could return fire. Due to the fog, the Germans could not pinpoint the origin of the fire. As they looked around anxiously, the Shermans popped up over the crest of the ridge and finished off the four remaining Panthers. As the action on the ground escalated, Bazooka Charlie again entered the fray, this time successfully striking two German tanks with his rockets from an altitude of 1,500 feet.

At 9:30 AM another German tank column approached CCA’s command post. CCA’s command center had ordered B Company, 37th Tank Battalion to shift to CCA’s command center. B Company arrived at its destination 45 minutes later. To deal with the developing threat, C Company, 37th Tank Battalion deployed on a ridge 500 yards from the command post. Sending salvos of 75mm armor-piercing shells at their antagonists, the Shermans knocked out several enemy tanks.

A German force of 14 tanks neared CCA’s headquarters at 12 PM. This was the southernmost assault of the day. Although it is not known exactly which German unit made the assault, it likely was the 111th Panzer Brigade. In a series of quick engagements, the platoon of Hellcats assigned to shelter the headquarters knocked out eight Panther tanks. The remaining Panthers withdrew rapidly.

At mid-afternoon, A Company, 37th Tank Battalion, which was part of Task Force Hunter sent to Luneville the day before, returned to Arracourt. Clarke and Abrams immediately paired A Company with B Company. “Dust off the sights, wipe off the shot, and breeze right through,” they instructed the company leaders. The two tank units then swept across the zone east of Arracourt. Leaving a single tank platoon from A Company to guard CCA’s command post, Hunter formed up southwest of Rechicourt with 24 Shermans and Dwight’s Hellcats.

Within minutes, the American tankers were hitting the remaining enemy armor in the area from front and flank, resulting in eight German tanks knocked out and approximately 100 German infantry casualties. The Americans lost three tanks. This was the last major engagement of the day. The U.S. forces engaged reported losing a total of five Shermans, three Hellcats, and six killed and three wounded.

As night fell, the 113th Panzer Brigade withdrew to Moncourt having suffered the loss of 43 tanks, mostly Panthers, and approximately 200 infantry. Due to its late disengagement at Luneville on September 18, coupled with its late arrival at its staging point for the attack on Arracourt on the following day, the 111th Panzer Brigade played virtually no part in the battle on September 19. As a result, the 113th Panzer Brigade attacked alone and unsupported. Nevertheless, OKH ordered Manteuffel to continue the attack the next day.

Although outnumbered 130 tanks to 45, Manteuffel instructed Kruger’s 58th Panzer Corps to attack from Arracourt toward Moyenvic on September 20 using the 111th Panzer Brigade. If repulsed, the Germans were to draw the Americans back to the Marne-Rhine Canal where flak guns and tanks from Panzer Brigade 113 awaited them.

American opposition on that day included not only the 37th Tank Battalion and some tank destroyers, but also the 35th Tank Battal- ion, 10th Armored Infantry Battalion, 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion, and three field artillery battalions.

On the morning of September 20, in accordance with Patton’s orders of the previous day, 4th Armored Division advanced toward the German border. The Americans advanced in the early morning in two columns. Abrams led the 37th Battalion and Lt. Col. Charles Odems led the 35th Tank Battalion.

Trailing the American columns was Clarke’s command post, which was attacked by the lead elements of the 111th Panzer Brigade. The threat was relieved by the lively fire from the towed guns of the 191st Field Artillery Battalion, which fired its 155mm howitzers at a range of only 200 yards. After two tanks were hit, the rest of the German force withdrew. U.S. forces sent to assist the headquarters destroyed five Panther tanks that day.

By late morning, the two U.S. task forces had traveled six miles from their start line. Fearful that more German forces were in the Parroy Forest sector and might attack the division’s rear, Wood returned both task forces to Arracourt to clear that region of the enemy.

After returning to his launch point, Abrams sent a team composed of tanks and armored infantry to the north of the Parroy Forest. When C Company, 37th Tank Battalion crested a rise near the town of Ley, it was met by a German ambush containing tanks and 75mm Pak 40 antitank guns. The first German volleys destroyed six Shermans. In return, the Americans knocked out seven German tanks and three enemy antitank guns.

Later in the day, A Company, 10th Armored Infantry Battalion and A Company, 37th Tank Battalion took Moncourt. They did this by ini- tiating the assault with tanks and following up the armored attack with an infantry assault. By day’s end, the Germans had lost 16 tanks, 257 dead, and 80 captured. The 111th and 113th Panzer Brigades had only 54 tanks left from the 180 with which they started the offensive. The U.S. 4th Armored Division lost 18 Shermans.

The 4th Armored Division rested on September 21, and the Germans reinforced their strike force at Arracourt with elements of Generalleutnant Wend von Wietersheim’s 11th Panzer Division from the Alsace area. Unfortunately for the Wehrmacht, the 11th Panzer Division, to which the 111th Panzer Brigade was attached, had a tank strength of just 40 Panthers and Panzer IVs.

In the predawn hours of September 22, the 11th Panzer began its mission to seal off the 4th Armor’s penetration by gaining control as far west as the Bezange Forest-Arracourt Blois de Benamont area. The attack was redirected to seize the village of Juvelize and then push north through Lezey. A supporting thrust was to be made by the 113th Panzer Brigade toward Ley.

The first encounters of the day occurred around 9:15 AM in thick fog between light Stu- art tanks of the screening D Troop, 25th Cavalry Squadron and German panzergrenadiers aided by 12 tanks, which quickly destroyed four American Stuarts. Hellcats from B Com- pany, 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion, responded to the German assault and knocked out three Panthers before withdrawing. In response, B and C Companies of the 37th Tank Battalion deployed between Juvelize and Lezey and beyond the latter town.

By noon, elements of 111th Panzer Brigade had occupied Juvelize, while the 113th reached Lezey. During their advance, American ground attack aircraft struck both panzer brigades. To block the enemy’s move any farther south, Abrams established a defensive line consisting of tanks from two of his companies, supported by infantry, on Hill 257 just northwest of Juvelize. As German armor continued to advance, American tanks on Hill 257 fired on them at ranges from 400 yards to 2,000 yards, destroying 14 tanks and effectively stopping the enemy’s attempt to reinforce the town. Abrams then ordered his B Company, together with A Company, 10th Armored Infantry Battalion, to take the town. They successfully achieved their objective. The 111th Panzer Brigade subsequently withdrew from the area.

German casualties at Juvelize amounted to 16 tanks, 250 men killed, and 185 captured. The U.S. forces engaged lost seven killed and 13 wounded. As for equipment, the Americans lost seven Stuarts and one Sherman tank.

On September 23, the Germans licked their wounds and waited for the remainder of the 11th Panzer Division. As for the Americans, Patton’s desire to continue his advance toward Germany was frustrated by a lack of supplies, which were being funneled to the Allied forces engaged in Operation Market Garden in Holland. As a result, Eisenhower ordered Patton to switch to the defensive.

On September 24, the 11th Panzer Division advanced on the lightly defended town of Moyen- vic. Over the next few hours the Germans conducted small battalion-sized probes supported by a few tanks against the Americans, but each probe was repulsed. The Germans lost 10 tanks and 300 troops.

The following day, the 11th Panzer Division made a minor attack from Moyenvic. Larger assaults were made at Juvelize, Lezey, and Ley. By this time, the 4th Armored was in the process of shortening its defensive line by pulling back to Rechicourt-Arracourt. That day, CCA and CCB reported destroying 10 enemy tanks and killing 300 enemy soldiers, while suffering 212 casual- ties. The fighting on September 26 was limited due to bad weather. However, the two sides exchanged artillery fire.

The tempo picked up on September 27 when Manteuffel sought to secure Hills 318, 265, and 293 on the southern flank of 4th Armored guarded by CCB. These hills overlooked the German positions in the Parroy Forest and placed any German movement there under the threat of American artillery and tank fire.

The 224 men of A Company, 10th Armored Infantry Battalion, who were deployed between Hills 265 and 318, put up a spirited defense of their position that day. They held their ground in the face of repeated assaults by tanks and infantry from the 11th Panzer Division throughout the long day.

Meanwhile, the 110th Panzergrenadier Regiment supported by tanks from the 11th Panzer Division attacked C Company and a platoon of tank destroyers holding Hill 265. A German battle group took Hill 318 from elements of the U.S. 51st Armored Infantry Battalion in heavy fighting, which sparked continuous fighting over the next 24 hours. The struggle for neighboring Hill 265 was almost as intense with the Americans barely holding the high ground. They were able to hold on primarily because of strong artillery support.

In preparation for a last-ditch effort to capture Hills 265 and 318, Wietersheim sent reinforcements to the German units deployed opposite CCB’s positions on the two strategic hills. On September 29, the 111th and 113th Panzer Brigades, as well as portions of the 110th Panzergrenadier Regiment, made a coordinated assault on the objectives. The early morning attack, in dense fog that limited observation to a few dozen yards, pushed the 51st Armored Infantry back 500 yards. This gave the Germans control of the forward crest of Hill 318 by late morning.

In response, Clarke sent a company of Sherman tanks from the 8th Tank Battalion to retake the hill, and the fighting reached a new level of intensity. The fog lifted just in time for P-47 Thunderbolts of the U.S. 405th Fighter Group to foil the next German attack. The air strikes forced the German tanks into the clear where they were systematically picked off by American artillery and tank fire.

In the afternoon, the Germans were forced to retreat from Hill 318 after a loss of 23 tanks. At Hill 265, the Germans pushed the Americans back to the reverse slope, but the Americans held on. With no reinforcements expected, the Germans abandoned the height.

The fighting on September 29 marked the last major attempt by the Fifth Panzer Army to cut Third Army’s armored spearhead near Arracourt. The failed effort of the previous four days cost the Germans 36 tanks, 700 killed, and 300 wounded.

The end of September 1944 found the fighting in Lorraine at a stalemate. Deprived of supplies, Patton could not switch to the offensive. As for the German Army, its panzer force had been so badly mauled that it was incapable of further offensive action against Patton’s Third Army.

Patton’s next challenge was to capture fortress Metz on Third Army’s left flank. After Metz fell to the Americans on December 13, Third Army advanced toward the Siegfried Line. Before Decem- ber was over, Patton’s Third Army would be engaged in another great armored clash, known as the Battle of the Bulge.

Once again, the author has failed to include the critical part the 2d Cavalry Group played in this action, other than the brief mention of the 42d Squadron M-8 being hit to start the battle. It was a coordinated attack on the 16th of September 1944 by 42d Squadron from the south, southeast, southwest, and east that ran the Germans out of Luneville and secured the city.

And it was the 42d Squadron who first engaged the German tanks on the 18th as they were given the mission to delay the German advance on Luneville until the rest of the 2d Cavalry Group could withdraw through the town. On this day in Luneville, the commander of the 42d Squadron, Lt. Col. Pitman, was KIA, and the 2d Cavalry Group commander, Col. Reed, was seriously wounded.

Thank you for pointing out the omission. My Dad was in Co. C, 42nd Squadron.

For more on the 2nd Cavalry Group, please see our story:

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/cavalrymen-stand-at-luneville/