By Pat Mctaggart

The latter half of 1943 had German forces in the east staggering under a series of hammer blows that saw the Soviet Red Army advance hundreds of kilometers westward on the central and southern sectors of the Eastern Front. After the massive battle in the Kursk salient, the Soviets launched their first great summer offensive late in July.

In a month and a half, Smolensk, Bryansk, and Kirov had been liberated in the central sector, with German forces retreating to the Sozh River and beyond. By September 30, Soviet troops had taken most of the northern shore of the Sea of Azov in the southern sector and had recaptured key cities that included Kharkov, Stalino, and Poltava while pushing the Germans back almost to the Dnieper River.

Luckily for the Germans, the Soviets outran their supply lines and had to call a halt to operations while men and material were brought forward. Both sides had suffered horrendous losses since July 1, and although the Russians could replace theirs with conscripts from newly liberated territory, it would take time to outfit them and give them the basics of command and combat.

While German forces battled the Soviets in a fighting retreat, thousands of forced laborers and German engineers were tasked with building a massive defensive line. On August 11, Hitler signed an order calling for the construction of the so-called “Eastern Wall.” Although it went against his propensity to fight for every foot of conquered land, Hitler had to face reality for once after the post-Kursk Soviet offensive.

The Wotan Line and the Panther Line

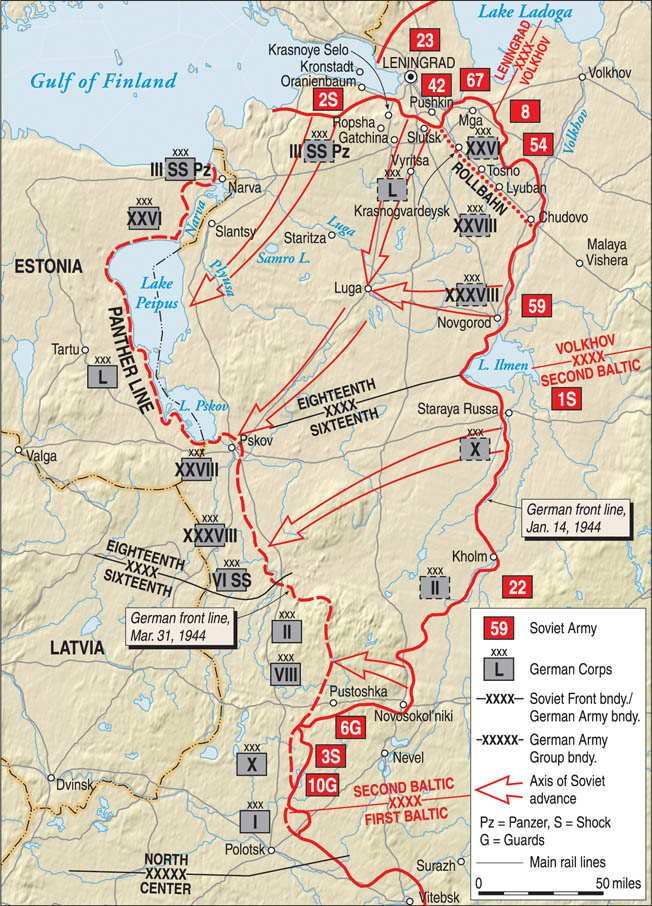

The line was to run from the Black Sea to the Baltic States. In the south, the majority of the defenses would be along the western bank of the Dnieper. North of Kiev it would run along the Desna River to Chernihiv and then continue northward in a line east of Gomel, Orsha, Nevel, and Pskov, ending on the southern tip of Lake Pskov. Continuing north along the western shore of Lake Pskov, it would then follow the Narva River north to the Gulf of Finland.

Toward the end of August, OKH (Oberkommando des Heeres—the German Army High Command) adopted two code names for the northern and southern sectors of the line. The part of the Eastern Wall that would eventually be manned by Army Groups A and South would be the “Wotan Line,” while the area occupied by Army Croups Center and North was code named the “Panther Line.”

Once it was fully constructed and manned, Hitler hoped his Eastern Wall would be such a formidable barrier that the Red Army would bleed itself dry trying to penetrate it. In essence, it would be a throwback to the trench warfare and the battles of attrition that Hitler himself had experienced in World War I.

There were three basic problems with the line. The first was the time it would take to construct. Soviet advances had already pushed German troops dangerously close to the proposed line, with some already occupying the half-built defenses. The second was manpower. Once the position was finally reached, some German units were so depleted that there was only one soldier to every 50 meters of front.

The third problem concerned the extreme southern sector of the Wall. Since the Dnieper curved west around Zaporizhzya to empty into the Black Sea west of the Crimean Peninsula, the line stretching from Melitopol to Zaporizhzya was constructed on land totally unsuited for its purpose since there was no river barrier to use as an additional plus for defensive positions. The Germans were forced to hold that area to protect the 17th Army, which occupied the Crimea.

The Collapse of the Wotan Line

Once reinforcements and supplies arrived, the Russians continued to batter the Germans. Kiev fell to the Red Army in November, and the 4th Ukrainian Front broke the lines of the German Sixth Army, which was holding the Melitopol area. Farther north, Soviet troops were able to establish bridgeheads across the Dnieper, taking several key positions in the half-completed Wotan Line. By the end of the year, most of the vaunted line had been overrun in the central and southern sectors of the Eastern Front.

While the situation was deteriorating in the center and the south during the summer, the sector occupied by Field Marshal Georg von Küchler’s Army Group North remained eerily quiet. The army group had been besieging Leningrad since 1941, and the front in that sector had been the object of several heavy Soviet attacks throughout the next two years, but the lines remained relatively stable.

In August, von Küchler received intelligence indicating a Soviet buildup in the Oranienbaum bridgehead—an area on the coast of the Gulf of Finland west of Leningrad that was held by the 2nd Shock Army. Farther south, in the sector held by General Christian Hansen’s Sixteenth Army, reports showed that a buildup was also occurring at the boundary of Army Group Center and Army Group North opposite the key rail junction city of Nevel.

Von Küchler responded to the possible threats by pulling five divisions out of the line to form a ready reserve to counter any Soviet attacks. Two of those divisions were lost almost immediately as Hitler, over the objections of the army group commander, sent them south to prop up other sectors of the front.

As Army Group Center withdrew to the Panther Line, Army Group North acquired General Karl von Oven’s XLIII Army Corps, which had occupied the northern flank of the retreating army group. This gave von Küchler three more divisions, but it also made him responsible for another 77 kilometers and the towns of Nevel and Novosokol’niki, which were the key communications centers between Army Group Center and Army Group North.

Making Gaps in the German Line

During the first week of October, a heavy overcast prevented further German aerial reconnaissance from taking place. This gave an opportunity for General Andrei Ivanovich Eremenko’s Kalinin Front (renamed the 1st Baltic Front on October 12) to move into attack positions without fear of German discovery.

On October 6, Lt. Gen. Kuzma Nikitovich Galitskii hit the 2nd Luftwaffe Field Division, which was occupying the northernmost sector of Army Group Center, with four rifle divisions and two tank brigades from his 3rd Shock Army. The 21st Guards Division and 78th Tank Brigade sliced through the German division, scattering its forces. Following units of the attack force poured through the lines of the disintegrating division and swung northeast toward Nevel. The poor showing of the 2nd Luftwaffe and other Luftwaffe field divisions prompted Hitler to approve the transfer of most of them to the Army, where they were known as feld (L) divisions. The neighboring 4th Shock Army also pushed forward, and by mid-afternoon the town was in Soviet hands.

Trying to restore the situation, von Küchler ordered his three remaining reserve divisions to attack the Russians around the town. Those units arrived piecemeal and had little effect in stopping the superior Soviet force, which had opened a gap of 24 kilometers between Army Groups North and Center.

Elements of only one reserve division were in the fight. Movement of the other two divisions had been disrupted by partisans, who had blown up the rail lines running directly to the town. With the resulting delay, von Küchler ordered German forces around Nevel to go into a defensive posture.

At the same time, the Soviet commanders called a halt to their offensive. The success of the initial assault had surprised the Russians, who had expected heavier enemy resistance. They now started to fortify their flanks, having learned bitter lessons in the past about the German tendency to let a salient develop before launching counterattacks that could, and in many cases did, trap and destroy the foremost elements of Soviet assault forces.

The impasse continued until November 2. Advancing under the cover of heavy fog, the 3rd and 4th Shock Armies hit Army Group Center’s Third Panzer Army, causing a 16 kilometer gap in the line. This allowed the 3rd Shock Army to turn northeast and hit Hansen’s Sixteenth Army flank. Von Küchler reacted by sending six battalions from General Georg Lindemann’s Eighteenth Army to Hansen, who used them to bolster his right flank. With the arrival of those troops the flank bent but did not break.

A Weak German Counterattack

By now, Hitler was livid. Not only had the Nevel salient remained intact—the new Soviet assault threatened to unhinge the entire front in the northern sector. He demanded that a counterattack eliminate the new bulge with a concentrated action by both Army Groups North and Center beginning on November 8.

Von Küchler objected in the strongest terms. He pointed out that the only way he could attack was to further weaken the Nineteenth Army, which was still in a static mode around Leningrad and Oranienbaum. He also pointed to German intelligence concerning a Soviet buildup in those areas. With the onset of winter, he was worried that a new enemy attack would occur in those areas since a Soviet offensive had occurred every winter since the war in the East had begun.

Hitler remained unmoved. He ordered that Army Group Center begin its attack on November 8, with von Küchler joining in on the 9th. An infantry and panzer division opened the attack on the 8th, making surprisingly good progress and advancing eight kilometers. The following day von Küchler postponed his own attack, saying no units could be spared for the assault. Furious, Hitler demanded that Army Group North begin its attack no later than November 10.

On the 10th, von Küchler made a halfhearted attempt to follow Hitler’s order by throwing just seven battalions against the Soviet northern flank. Russian artillery fire, followed by a counterattack, threw the Germans back with heavy losses. Once again, the debate over priorities raged between Hitler and his commander.

The Eighteenth Army Stretched Thin

While the two argued, the Soviets pressed forward. Their new salient was extended to a depth of 80 kilometers. A new threat appeared when the Russians started to turn east at the tip of the salient, threatening the right flank of the Sixteenth Army and bringing Red Army troops dangerously close to Novosokol’niki.

Von Küchler was summoned to Hitler’s headquarters, where the two heatedly discussed the new threat. Although obsessed with the Nevel bridgehead, Hitler finally agreed that Soviet forces threatening the flank should be dealt with before continuing to try and stabilize things at Nevel.

Once again it was Lindemann who paid the price with the loss of another division from his Eighteenth Army. Although his front still remained quiet, the gradual transfer of one division after another to the south stretched his defenses dangerously thin. The feld (L) divisions under his command held purely defensive positions and were of questionable combat worthiness, while regular army divisions were rarely up to strength.

Before von Küchler, who was waiting for the transferred division to arrive in the south, could attack, an assault by the 11th Guards Army hit Army Group Center on November 21. The two divisions that had attacked the Soviet bulge on November 8 were withdrawn to meet the new threat, further weakening Army Group North’s plan to reduce the salient. A sudden thaw in the last week of November further disrupted the German plan as the ground turned into a quagmire, forcing a postponement of the attack until December 1.

When the attack finally did get under way, the German divisions advanced a mere five kilometers into the Soviet bulge. Mechanized vehicles became stuck in the mud, and each step for the infantry became a struggle with nature. Even Hitler recognized the futility of continuing the attack on the Soviet western flank, so he ordered a halt to the assault and ordered von Küchler to resume plans to pinch off the Nevel salient.

Pulling Back From the Nevel Bulge

For the rest of December the Soviets in the western bulge took time to refit and regroup. They could be happy with the results of the previous month, as they had managed to make a considerable advance that endangered both Army Group Center and Army Group North. However, they had outrun their supply lines, and reinforcements to replace casualties that had been taken were being held in reserve for the general winter offensive that was being planned in Moscow.

Hitler finally realized that the Nevel salient could not be destroyed on December 16. Enemy pressure on the Third Panzer Army had forced the German line in that sector even farther back, endangering the communications hub at Vitebsk. For the next 10 days he kept a close eye on developments in the Vitebsk area while leaving the affairs of Army Group North to von Küchler.

On December 27, Hitler accepted von Küchler’s request to shorten his lines. The withdrawal took troops out of the Nevel bulge and pulled them back to a line running from just south of Novosokol’niki west toward Pusloshka. The pullback gave Hansen more troops to man the line and reinforce positions along the front in the west.

It should be noted that Army Group North was the only army group that had not yet retreated to the Eastern Wall’s Panther Line. Since September, a force of some 50,000 civilians and engineers had worked on the line in the north, building about 6,000 bunkers and laying 200 kilometers of barbed wire. Another 40 kilometers of trenches and antitank ditches were also dug. In addition, a series of secondary positions were also constructed, with strongpoints being built at Narva, Chudovo, Kingisepp, Luga, Krasnobvardeisk, and Novgorod.

Operation Blue: The German Retreat

The plan for retreating to the Panther Line started in September. It was codenamed Operation Blue. One of the main concerns that Army Group North planners had was the 900,000 civilians living in the area that was to be evacuated. It would be impossible to move them all, so security forces in the rear areas singled out adult males that would either be conscripted by the advancing Red Army or be used as workers for the Soviet war effort. In total, some 250,000 men had been forcibly transported to Latvia and Lithuania by the end of the year. Hundreds of thousands of tons of grain and potatoes were also scheduled to be sent to safe areas along with half a million cattle and sheep.

Planning for the retreat envisioned a staggered withdrawal that would start in mid-January and continue for the next couple of months until the spring thaw. However, on December 22 Hitler decided that he would not approve the implementation of Operation Blue unless the Soviets began a general offensive against the army group.

Toward the end of the month, the Eighteenth Army lost one of its best divisions, the 1st Infantry, which was sent south to shore up the front. Two more divisions were also transferred during the first days of January. With each loss, von Küchler protested directly to Hitler with no results. In return for these losses, Hitler sent SS Lt. Gen. Felix Steiner’s III SS Panzer Corps to bolster the Oranienbaum sector.

German Order of Battle At the Line

At the beginning of 1944, the units of Lindemann’s Eighteenth Army around Leningrad and the Oranienbaum bridgehead were stretched to the limit. The line surrounding Lt. Gen. Ivan Ivanovich Fediuninskii’s 2nd Shock Army was manned by Steiner’s Corps (SS Police Division, SS Nordland Division and 9th and 10th Feld (L) Divisions). The SS Nederland Brigade was also in transport to the corps.

A half circle ring on the southern sector of Leningrad ran from the Gulf of Finland about 30 kilometers southwest of the city through Pushkin and ended at the Neva River. General Wilhelm Wegner’s L Army Corps (126th, 170th, and 215th Infantry Divisions) and General Otto Sponheimer’s LIV Army Corps (11th, 24th, and 225th Infantry Divisions) occupied the sector. Facing Soviet units around the Siniavino Heights and the Pogos’te pocket was General Martin Grase’s XXVI Army Corps (61st, 121st, 212th, 227th, 254th Infantry and 12th Feld (L) Infantry Divisions and the Spanish Legion, composed of Spanish volunteers who had served in the withdrawn 250th “Blue” Division).

The final sector held by the Eighteenth Army was an area on the Volkhov River running from Kirishi to Novgorod. Along the river line were General Herbert Loch’s XXVIII Army Corps (21st, 96th, and 13th Feld (L) Infantry Divisions) and General Kurt Herzog’s XXXVIII Army Corps (2nd Latvian SS Brigade, 28th Jäger (Light) Division, and 1st Feld (L) Infantry Division).

South of Lake Ilmen, Hansen’s Sixteenth Army still maintained contact with Army Group Center. General Thomas Wickede’s X Army Corps (8th Jäger Division and 30th and 21st Feld (L) Infantry Divisions) held a line from Lake Ilmen to Kholm. On Wickede’s right flank, General Paul Laux’s II Army Corps (218th and 93rd Infantry Divisions) and SS Lt. Gen. Karl von Pfeffer-Wildenbruch’s VI SS Army Corps (331st and 205th Infantry Divisions) front ran from Kholm to the Novosokol’niki Heights. Holding the Nevel area were General Karl von Oven’s XLIII Army Corps (15th Latvian SS Division and the 83rd and 263 Infantry Divisions) and General Carl Hilpert’s I Army Corps (58th, 69th, 23rd, 122nd, and 290th Infantry Divisions). The final sector, running from Putoshka to Lake Nezherda was occupied by General Gustav Hoehne’s VIII Army Corps (81st and 329th Infantry Divisions and SS Combat Group Jeckeln).

The Soviets Prepare Their Grand Offensive

While the Germans were planning Operation Blue, general planning for a grand offensive against Army Group North began as early as September when Volkhov Front commander General Kirill Anfansevich Meretskov and Leningrad Front commander General Leonid Aleksandrovich Govorov presented almost identical ideas to Stavka (Soviet High Command). The plans called for offensives by both Fronts designed to cut off and destroy the Eighteenth Army before it could withdraw to the Panther Line.

On October 12, Stavka approved the initial plan and set about refining it. Included in the final operational plan was a two-pronged attack with the 2nd Shock Army bursting out of the Oranienbaum bridgehead and Col. Gen. Ivan Ivanovich Maslennikov’s 42nd Army attacking to the southwest from Leningrad.

The two armies were to link up at Ropsha about 25 kilometers southwest of Leningrad, trapping the German divisions that occupied the corridor between Leningrad and Oranienbaum. While the pincer attack was under way, Govorov would use Lt. Gen. Vladimir Petrovich Sviridov’s 67th Army to tie down German forces south of Leningrad. Once the first phase was accomplished, the three armies were to move westward and southwestward, overcoming other German divisions that were trying to reach the Panther Line.

On the Volkhov Front, Meretskov would use Lt. Gen. Ivan Teretevich Korovnikov’s 59th Army as his battering ram. Korovnikov would hit Herzog’s XXXVIII Army Corps with a force of nine divisions north of Novgorod while a smaller force would attack across the frozen Lake Ilmen. The two forces would then converge west of Novgorod, surrounding the city and eliminating German units trapped inside that pocket.

Farther south, General Markian Mikhail-ovich Popov’s 2nd Baltic Front would attack the Sixteenth Army, tying down its forces and preventing any reinforcements being sent to the Eighteenth Army. All three Fronts would be assisted by partisan brigades that occupied areas in the German rear. Those brigades were tasked with disrupting supplies and communications throughout the region.

105,000 Soviet Shells

Under cover of darkness, Soviet units moved into their well-camouflaged jump-off points on January 12 and 13. Massive piles of shells lay beside the artillery battalions of all three Fronts as the gunners zeroed in on preplotted enemy positions. Heavy snow began to fall as the clock ticked down to midnight, further concealing Russian assault units’ movements.

The snow added a surreal picture to the landscape as German soldiers in outposts strained to see into the area before them. Visibility was almost zero, and it was eerily quiet. Suddenly, the stillness was broken by the hum of motors overhead.

With the help of the partisans and aerial reconnaissance, the Soviets had pinpointed the weakest points in the German line. In the sector of Steiner’s Corps those points were in the positions of Colonel Ernst Michaels’ 9th Feld (L) and Brig. Gen. Hermann von Wedel’s 10th Feld (L) Divisions, which ran from the Gulf of Finland at Peterhof southwest to Zaostrovye. Although these former Luftwaffe divisions had been transferred to the Army, their personnel still lacked the basic ground combat skills of their Army comrades.

The noise grew louder as more than 100 Soviet night bombers approached. Even though the snow prevented visibly identifying targets, the Russians dropped their loads with credible accuracy. The German positions erupted in flames and explosions as the bombers passed overhead. For the rest of the night the troops of the two divisions frantically worked on rebuilding their shattered defenses and gathered their dead and wounded while worrying what would come after the raid.

At 0935 on the 14th, they found out. As the snow abated, the sky in the distance turned yellow and red as the Leningrad Front unleashed hell on the two divisions and other units of Steiner’s corps. In a 65-minute bombardment the Soviet artillery, assisted by guns of the Red Navy, fired almost 105,000 shells, obliterating the enemy defenses. The bombardment ended in a screaming crescendo as battery after battery of Katyusha rockets plunged into the German positions.

The Russian Advance Begins

As the artillery fire ended, Maj. Gen. Anatoli Iosiforovich Andreev’s 43rd Rifle Corps (48th, 90th, and 98th Rifle Divisions) and Maj. Gen. Pantelemon Aleksandrovich Zaitsev’s 122nd Rifle Corps (11th and 131st Rifle Divisions) hit the two former Luftwaffe divisions. They were supported by the 122nd and 43rd Tank Brigades. As they penetrated the shattered German lines, pockets of resistance desperately tried to stem the Russian advance to no avail.

The assault units were followed by the 43rd, 168th, and 186th Rifle Divisions and the 152nd Tank Brigade, which wiped out or captured any Germans that had survived the initial attack. By nightfall the Russians had overrun most of the primary German defensive positions, and Michaels and von Wedel’s divisions had virtually disintegrated.

Survivors of the divisions were rounded up by officers to form hedgehog positions in villages south and west of the breakthrough points. While Michaels formed combat groups in his sector he ordered a Lt. Col. Lassman to set up an all-around defense at the road junction at Ropsha. Lassmann sent out patrols to pick up stragglers from the front line and slowly formed his defense force.

The Russians continued to advance overnight, with Colonel Nikolai Georgovich Liashenko’s 90th Rifle and Colonel Petr Loginovich Romanko’s 131st Rifle Divisions, supported by Col. A.Z. Oskotskii’s 152nd Tank Brigade and the 2nd and 204th Tank Regiments, gaining an additional four kilometers of ground in the German’s secondary defense line. Additional reinforcements and heavy Soviet artillery fire prevented any threat of a counterattack to close the gap.

Attack Near the Pulkovo Heights

January 15 saw Maslennikov’s 42nd Army join the assault. The preliminary artillery barrage was even more impressive than the one the day before. About 2,300 guns, mortars, and rocket launchers hit a 17-kilometer section of the German line from Uritsk to Pushkin with more than 220,000 shells. At 1100, Maj. Gen. Nikolai Pavlovich Simoniak’s 30th Guards Rifle Corps attacked the center of the mangled enemy line west of the Pulkovo Heights with his 45th, 63rd, and 65th Guards Rifle Divisions, which were supported by Lt. Col. I.V. Protsenko’s 220th Tank Brigade.

The sector was held by the seasoned troops of Wegner’s L Army Corps, who had fared better through the bombardment than their comrades had the previous day. Strong primary and secondary positions had been built, and bitter fighting took place for every meter of ground. Bearing the brunt of Simoniak’s attack, Brig. Gen. Walther Krause’s 170th Infantry Division was forced to give up about five kilometers of ground to the well-trained and well-disciplined Guards divisions.

The 170th gave ground grudgingly, but not without cost. In Lt. Col. Johannes Arndt’s 131st Infantry Regiment, two battalion commanders, Captain Moeller and Captain Meyer, were killed while directing the defense. Their men held their positions and withdrew only when Russian troops threatened Arndt’s command post.

On Siamoniak’s right flank, Maj. Gen. Ivan Prokofevich Alferov’s 109th Rifle Corps had a tougher time as they tried to breach the defenses of Maj. Gen. Gotthard Fischer’s 126th Infantry Division. Alferov’s three rifle divisions (72nd, 189th, and 125th) only managed to advance about 1.5 kilometers against the determined German resistance.

It was the same on the left flank where Maj. Gen. Stepan Mikhailovich Bun’kov’s 56th, Colonel Konstantin Vladmirovich Vvedenskii’s 85th, and Colonel Sergei Petrovich Demidov’s 86th Rifle Divisions of the 110th Rifle Corps (Maj. Gen. Ivan Vasilevich Khozov) hit Maj. Gen. Bruno Frankewitz’s 215th Infantry Division. The costly advance through Frankewitz’s primary positions only gained as much ground as Alferov had.

The Nordland Division Counterattack

Almost 20 kilometers to the west in the III SS Panzer Corps sector, von Wedel and Michaels’ divisions were still holding out in some pockets. Meanwhile, Fediuninskii committed more forces into the expanding wedge in the German line. With the additional manpower the Russians were able to thrust forward to Sokuli, which fell after heavy fighting. With the capture of the town, the 2nd Shock Army was only a few kilometers from Ropsha.

Watching his lines crumble, Steiner ordered SS Brig. Gen. Fritz von Scholz’s Edler von Barancze’s 11th SS Panzergrenadier Division “Nordland” to counterattack. The Nordland Division was composed of Scandinavian volunteers (10 percent), native Germans (30 percent), and ethnic Germans from Romania. Among its members was Norwegian John Sandstadt, a member of the 1st Company of Nordland’s 23rd Panzergrenadier Regiment, who described the action:

“The counterattack collapsed completely under Soviet crossfire. We immediately lost 13 dead and many wounded. It was the same for the 2nd and 3rd companies. All the same, we were finally able to hold our [old] positions for some 10 days, with our three companies being reduced to the strength of one company.”

For the next two days the Soviet juggernaut pushed forward. On the 16th, the Volkhov Front’s 54th Army (Lt. Gen. Sergei Vasilevich Roginskii) attacked Loch’s SS VII Army Corps with the city of Lyuban as its objective. The attack faltered almost immediately as it ran into the prepared positions of Brig. Gen. Hellmuth Preiss’s 121st, Colonel Gottfried Weber’s 12th Feld (L), Brig. Gen. Johann-Albrecht von Blücher’s 96th, and Maj. Gen. Gerhard Matzky’s 21st Infantry Divisions.

A Soviet report stated: “The direction of the attack is toward Lyuban. However, the enemy’s resistance still has not been overcome. He is continuing to cling fiercely to every clump of ground and launching counterattacks. It is requiring bravery and selflessness to overcome him.”

The Battle For Krasnoye Selo

On the 18th, Lindemann demanded that his frontline forces be allowed to withdraw. The 126th and remnants of the 9th Feld (L) were threatened with encirclement. The battle for Krasnoye Selo was beginning, and the pincers of Fediuninskii’s and Maslennikov’s armies were moving forward south of Ropsha, threatening further encirclements when they met.

At Ropsha itself, Lt. Col. Lassmann received a final radio message from Colonel Michaels, who was still holding out with some of his men at Tuganty, about 15 kilometers south of Lassman’s position. His combat group was fighting against the advance elements of Fediuninskii’s assault forces, trying to prevent them from linking up with the 42nd Army. After giving Lassmann a report on the situation, he signed off by saying, “In this life, we will never see each other again.” Four days later Michaels was killed while defending his position.

While Lindemann, Hitler, and von Küchler were still discussing a pullback, Maslennikov pushed more units to the front to exploit the gains being made by Simoniak. Lindemann had no reserves left, as he had already committed Maj. Gen. Günther Krappe’s 61st Infantry Division to the fight. Events overtook the debate as Ropsha fell to Zaitsev’s 122nd Rifle Corps. On January 19, lead elements of the 2nd Shock and 42nd Armies met south of the town, while Krasnoye Selo fell to Simoniak’s forces.

During the evening of the 19th, Lindemann ordered the 126th and 9th Feld (L) Divisions to break through the tightening Soviet ring and make their way south. Maj. Gen. Fisher regrouped his division and started out at midnight with his 424th Infantry Regiment in the lead. Assault guns guarded the division’s flanks as the men moved through the darkness. Since the Soviets still had only forward elements of the 42nd and 2nd Shock Armies occupying the area of the breakout, the 126th and remnants of the 9th Feld (L) managed to break through during the early hours of the 20th.

A 20-Kilometer Gap

While the battle for the Oranienbaum corridor was taking place, the Volkhov Front’s 59th Army hit Herzog’s XXXVIII Army Corps with three rifle corps. The objective was to take Novgorod and dislodge the right flank of the Eighteenth Army. More than 130,000 artillery shells heralded the opening of Korvnikov’s offensive on the 14th. At 1050 the Soviets launched their attack from a bridgehead on the western bank of the Volkhov, expecting little resistance from the artillery-riddled German positions.

As the three divisions of Maj. Gen. Semyon Petrovich Mikulskii’s 6th Guards Rifle Corps advanced, they were met with devastating fire from the Silesians of Maj. Gen. Hans Speth’s 28th Jäger Division. Mikulskii’s divisions were supposed to be supported by Colonel K.O. Urvanov’s 167th Tank Brigade, but the swampy terrain and craters created by the initial artillery bombardment prevented the tanks from arriving in time to help. As a result, the Soviets were able to advance little more than a kilometer.

Farther south, an operational group under the command of Maj. Gen. Teodor Andreevich Sviklin, the army’s assistant commanding officer, had more luck. Sviklin’s men were able to cross frozen Lake Ilmen south of Novgorod, catching the troops of Luftwaffe Brig. Gen. Rudolf Petrauschke’s 1st Feld (L) Division flat footed. Overcoming light resistance, Sviklin secured a six-kilometer-deep by four-kilometer-wide bridgehead on the eastern shore of the lake, threatening the communications line between Novgorod and Shimsk.

January 15 saw Mikulskii, now reinforced with a rifle division and a tank brigade, advance seven kilometers. His forces were able to cut the rail line, defended by elements of Maj. Gen. Kurt Versock’s 24th Infantry Division, between Chudovo and Novgorod. Supported by the three rifle divisions of Maj. Gen. Pavel Alekseevich Artiushenko’s 14th Rifle Corps, Mikulski was able to advance into the main German defensive line and create a 20-kilometer gap in the enemy defenses.

Breaking Out of Novgorod

At Novgorod, Colonel Lothar Freutel’s 503rd Infantry Regiment of Maj. Gen. Conrad-Oskar Heinrichs’ 290th Infantry Division, which had been rushed forward to bolster Petrauschke’s division, formed a defensive barrier in the ruins of the city. The defenders also included elements of Petrauschke’s and Speth’s divisions and were supported by the 290th Artillery Regiment.

Enveloped from the north and south, Novgorod held out until January 19, when a breakout order was given. A member of the combat group defending the city recalled:

“On the night of January 19, those troops of the 28th Jäger Division in Novgorod received the order to break out. The seriously wounded had to be abandoned in the ruins, the medical staff volunteering to remain behind with them, and all who could carry weapons, including the walking wounded, tried to withdraw under cover of darkness.”

The combat group broke down into smaller sections, which were constantly attacked by the Red Air Force and Soviet artillery. In Freutel’s regiment, only three officers and 100 men came through alive. It was the same for the other units that participated in the breakout. On the morning of January 20, Maj. Gen. Ivan Nikolayevich Burakovskii’s 191st, Colonel Petr Ivanovich Olkhovshii’s 225th, and Maj. Gen. Petr Nikolaevich Chernyshev’s 382nd Rifle Divisions entered the city, encountering no resistance.

Retreat to the Rollbahn Line

With the fall of Novgorod, von Küchler realized that his army group was being outflanked. He once again requested that Hitler allow him to retreat. Engaging in a back and forth argument about just how far back the troops would withdraw, Hitler grudgingly gave permission to retreat to the so-called Rollbahn Line, which was one of the secondary defensive positions that had been built earlier. The subsequent shortening of the line meant that three divisions could now be used as a reserve. Hitler also agreed to move Brig. Gen. Erpo von Bodenhausen’s 12th Panzer Division into Sixteenth Army’s area.

Popov’s 2nd Baltic Front, operating south of Meretskov, was also causing trouble for the Sixteenth Army, but its early assaults met with little success. By mid-January it had carved out a small bridgehead that had severed the Nevel-Leningrad rail line, but little else was achieved. Counterattacks from Laux’s II Army Corps and Wickede’s X Army Corps forced Popov to go onto the defensive on January 20, but the danger of a renewed Russian attack prevented any transfer of German troops in the area to other endangered sectors.

Stavka gave its Front commanders little time to consolidate their gains. With urging from Moscow, Govorov resumed his offensive on the 21st. Masslennikov’s 42nd Army was given a number of missions. His troops were ordered to take Slutsk, Pushkin, and Tosno and then drive on to capture the important road junction at Gatchina. The capture of that town would enable him to continue advancing to the Luga River, where the Germans had set up another line of defense.

Meretskov was also ordered to head for the Luga. He charged Korovnikkov’s 59th Army with that task. In conjunction with Korovnikkov’s attack, Roginskii’s 54th Army was to take Lyuban and encircle and destroy Loch’s XXVIII Corps.

The attacks were supported by partisan units, which totally disrupted the interior German lines of supply and communication. During the month of January partisans destroyed several stretches of railroad tracks, blew up more than 300 bridges, and derailed 133 trains. The attacks were devastating to German morale. The history of the 11th Infantry Division describes the effect on troops who did not receive much needed food or clothing:

“Often the troops go for days in the icy cold without warm food, with wet clothing that would freeze stiff, with merely crumbs of frozen bread to eat and frozen tea in their canteens to drink. They would catch a few minutes of sleep when they could.…”

“I am Against All Withdrawals”

On the 21st, Mga fell to Soviet forces after German troops in the city made an orderly retreat. Lt. Gen. Filipp Nikanorovich Starikov was ordered to use his 8th Army to pursue and destroy the garrison, but the pursuing forces were overly cautious and the Germans were able to make good their retreat.

Meanwhile, Wegner’s L Army Corps was fighting a desperate battle around Gatchina against the spearhead of the 42nd Army. Once again, von Küchler flew to Hitler’s headquarters to demand freedom of action. He wanted to shore up his line as much as possible, and he argued that German forces holding Pushkin and Slutsk would be destroyed if they were not allowed to retreat.

“I am against all withdrawals,” Hitler replied. He said that he wanted the Soviets to bleed and incur as many casualties as possible before they descended on the Panther Line. Von Küchler argued, to no avail, that when the army group would finally be allowed to retreat to the line, it might not have the troops to man it.

A frustrated von Küchler returned to his headquarters having received little from Hitler. His lines were tenuous at best, and one decisive Soviet breakthrough could mean disaster for the entire army group.

Soviets Repulsed at Gatchina

On January 23, Meretskov launched what he hoped would be a final assault on the German forces at Gatchina. The defenders now consisted of a hodgepodge of units centered around the L Army Corps (170th and part of the 215th Divisions). Other units manning defenses in the area were the remnants of Maj. Gen. Ernst Risse’s 225th and Krappe’s 61st Infantry Divisions. Arriving in the area were Major Willy Jähde’s Tiger Detachment 502 and elements of the 12th Panzer Division.

To help Maslennikov accomplish his mission, Govorov released Maj. Gen. Vasilii Alekseevich Trubachev’s 117th Rifle Corps and Maj. Gen. Georgii Ivanovich Anisimov’s 123rd Rifle Corps from the Front reserve. Maslennikov ordered his two new corps to make a frontal attack on the German defenses. Farther south, Maj. Gen. Ivan Vasilevich Khazov’s 110th Rifle Corps would encircle German forces at Pushkin and Slutsk.

After a short artillery barrage, Trubachev and Anisimov moved forward. The Germans met the attacking Russians with a wall of fire that decimated the first ranks, but more kept coming. Fighting continued throughout the day and into the night, but the German line held. Although two of his corps had failed in their initial mission to take Gatchina, Maslennikov was able to report that the Germans had been pushed out of Pushkin by Khazov on the 24th, and that Khazov was pursuing the retreating enemy.

Von Küchler Replaced by Model

The next few days saw the Soviet advance move at a steady, if slow, pace. The rail line between Gatchina and Kingisepp was cut on the 27th, and Fediuninskii’s 2nd Shock Army was pushing Grase’s XXVI Army Corps toward Kingisepp itself. As the German lines continued to deteriorate, Hitler ordered von Küchler to attend a National Socialist leadership conference in Königsberg on the 27th.

At the meeting, von Küchler once again confronted Hitler. He told the Führer that the Eighteenth Army had already lost 40,000 men and that retreat was the only way to save it. Hitler gave him little time to continue. He said that he expected the Eighteenth Army and Army Group North to continue to hold. Nothing was said of reinforcements being sent to help fulfill the order.

Unbeknownst to von Küchler, his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Eberhard Kinzel, had already started the ball rolling. While von Küchler was gone, Kinzel informed Colonel Friedrich Foertsch, chief of staff of the Eighteenth Army, that the army must retreat no matter what. Knowing that Berlin would never approve, Kinzel issued the order verbally rather that in writing.

The plan was put into action even as von Küchler was arguing with Hitler. Strong rear guards were left behind at critical junctions to slow the Soviets while the main body of troops headed for the Luga River line. Presented with a fait accompli, von Küchler had no choice but to go along with the withdrawal.

Hitler was furious when informed of the withdrawal. Von Küchler was relieved, and General (soon to be Field Marshal) Walther Model was sent to take his place. Model was a favorite of Hitler’s and was known as “The Führer’s Fireman.” He was one of the few German generals who could make decisions contrary to Hitler’s orders and get away with it.

Even before taking off for his new assignment, Model issued his first order to Army Group North. “Not a single step backward will be taken without my express permission,” he telegraphed to his army group headquarters. “I am flying to Eighteenth Army this afternoon. Tell General Lindemann that I beg his old trust in me. We have worked together before.”

Caspar Sporck’s Iron Cross

Things were going from bad to worse for the Germans, and not even Model could stop the Soviets with his call to stand fast. The Luga River line had already been breached by the Russians, who had established several bridgeheads on the western bank. Only lack of supplies prevented the Soviets from exploiting their gains immediately.

In Steiner’s sector, the remnants of his shattered divisions fell back toward Narva and Kinigsepp under heavy Soviet pressure. The men were exhausted from the constant combat. Nordland’s John Sandstadt recalled:

“When we had some rest on January 27 our company consisted of one 1st lieutenant, five NCOs, and some 35 men. Our battalion commander, Fritz Vogt, appeared and handed several soldiers, including me, the Iron Cross 2nd Class. [It was] less as recognition for brave deeds than as a ‘premium’ for having survived the last 12 days.”

Although their ranks had been whittled down by the Russians, the men of the Nordland Division made the Soviets pay for their gains. An example can be found in the exploits of 21-year-old SS Corporal Caspar Sporck, a Dutch volunteer in Nordland’s 11th Armored Reconnaissance Battalion. Sporck was the commander of an armored personnel carrier that mounted a 75mm gun and was attached to the battalion’s 5th (Heavy) Company.

When Soviet tanks broke through the German line and entered the village of Gubanizy, Sporck moved his vehicle forward into the village. Playing a deadly game of hide and seek, Sporck drove among the houses catching tank after tank in the sights of his low-velocity cannon. The sharp crack of the 75mm was followed by an explosion that marked another victim. In all, Sporck destroyed 11 enemy tanks and sent the survivors fleeing from the village.

A few days later, Sporck guarded the flank of the division as it disengaged and made its way across the Narva River. He directed stragglers to the crossing point while fending off enemy armored vehicles attempting to overrun the division’s rear guard. His vehicle was one of the last to cross over into the German positions.

Sporck was awarded the Knight’s Cross for his actions. He survived the battle for Narva, but his luck ran out a few months later when he was severely wounded at the Stettin bridgehead. He died of his wounds on April 8, 1945, just a month short of the end of the war.

Actions such as Sporcks’s might have slowed the Russians down a bit, but nothing could stop the Red Army steamroller. By the end of January the survivors of the German corps on Army Group North’s left flank were mostly across the Narva River. Sponheimer’s LIV Army Corps was in the process of reforming as Army Abteilung Narva, which would eventually consist of Steiner’s corps and the LIV and XXVI Army Corps. Elements of the Panzergrenadier Division “Feldherrnhalle” and the 58th Infantry Division were also on their way to strengthen the Narva front. An Estonian SS Division along with Jähde’s Tiger tank detachment would also be available to stop the Russians.

Those German units were the first of Army Group North to occupy its part of the Panther Line. The Narva River position would be the scene of several bloody battles, but the Germans would continue to hold for months to come. Now it was up to the German divisions south of Lake Pskov to beat the Russian advance to their portion of the line.

Push to the Luga River

The forced retreat of the Germans to the Narva was not the only thing Model had to deal with. On January 25 the Red Air Force bombed German defenses at Gatchina. Minutes later, Maj. Gen. Mikhail Fedorovich Tikhonov’s 18th Rifle Corps (196th, 224th, and 314th Rifle Divisions), supported by Lt. Col. V.I. Protsenko’s 220th Tank Brigade, hit the mixed bag of German forces defending the town. Combat groups of the 11th, 126th, 215th, and 225th Infantry Divisions and the 9th Feld (L) Division fought the Russians at every turn. The battle raged well into the night before Tikhonov called off the attack to regroup.

The next day the attack continued. This time elements of Trubachev’s 117th Rifle Corps joined in the assault. By noon, Colonel Aleksei Vasilevich Batluk’s 20th Rifle Division and Colonel F.A. Burmitstrov’s 224th Rifle Division had reached the center of the town, forcing the Germans to withdraw to prevent encirclement. Tosno fell on the same day.

During the next few days the Eighteenth Army conducted a fighting withdrawal to the Luga, which, as mentioned earlier, had already been crossed by advance elements of the Red Army. Under increasing pressure, the XXVIII and XXXVIII Army Corps were pushed back even more. Their escape route would be cut off if the bulk of the Soviets reached the Luga ahead of them.

To force a wholesale breach of the Luga Line in the retreating Germans’ sector, Mikulski’s 6th Guards Rifle Corps was given the task of taking the town of Luga. He would be supported by Maj. Gen. Filipp Iakovlevich Solovev’s 112th Rifle Corps. Meanwhile, Artuishenko’s 14th Rifle Corps would strike south toward Shimsk.

What was thought to be a relatively easy operation became a plodding nightmare for the Russians. Mikulskii’s troops, struggling through the uneven terrain, ran into stronger than expected German positions before finally reaching the Luga River. The steadfast German defense gave the XXVIII and XXXVIII Army Corps time to make good their escape, pulling back to new positions that prevented their destruction.

“Schild und Schwert”

In the Sixteenth Army’s sector, Popov was planning another attack with his 2nd Baltic Front that was designed to support Meretskov’s efforts in the north. Luckily for the Germans, their intelligence detected signs of the coming assault and Hansen ordered a withdrawal to new positions farther west on January 30. When the attack came it stalled as soon as the new German line was reached. The resulting shortening of the line allowed Hansen to send reinforcements to Lindemann to help him in his struggle.

As he looked at Eighteenth Army’s situation, Model knew his “not one step backwards” order was impossible to implement. As a remedy he introduced the “Schild und Schwert” (Shield and Sword) maneuver. Historian Earl Ziemke credits Hitler himself with the idea in which withdrawals were permissible “if one intended later to strike back in the same or different direction in a kind of parry and thrust sequence.”

Using Shild und Schwert, Model authorized Lindemann to move west to a shorter line north and east of Luga. He then planned to use von Bodenhausen’s 12th Panzer Division, Brig. Gen. Kurt Siewert’s 58th Infantry Division, and any other divisions that could be spared to attack along the Luga River and line up with the units on the Narva.

The Russians, however, had their plans too. After a reshuffling of forces, Govorov and Meretskov were ready to continue their assaults. The 2nd Shock Army had been reinforced for its attack on the Narva Line. Although Fediuninskii was able to make some gains south of the city of Narva, his continued assaults would develop into bloody brawls where attack was met with counterattack. Little would be accomplished except the shedding of blood by both sides.

Maslennikov had more success than his neighbor to the north. His 42nd Army was able to cross the frozen Luga River on January 31, pushing Wegner’s L Army Corps to the south and southwest. The battered German divisions could do little but retreat while Russian forces remained in hot pursuit and were able to advance as much as 15-20 kilometers a day.

Slow Moving For the 12th Panzer

Stavka now set its sights on finally taking Luga. German intelligence reported that two strong Russian forces, one southwest of Novgorod and the other east of Lane Samro, were massing and that an attack on Luga was imminent. To accomplish the mission, part of the 42nd Army was to advance on Luga’s northwestern sector. Roginskii’s 54th Army would attack the city’s outlying defenses from the east. Sviridov’s reinforced 67th Army would support Masslenikov’s forces.

Model had no choice but to act quickly. He ordered Lindemann to form a line stretching west of Luga to the southern shore of Lake Peipus. The 11th, 212th, and 215th Infantry Divisions, which had barely escaped encirclement days earlier, were charged with defending Luga with what was left of their forces. Brig. Gen. Hellmuth Reymann’s 13th Feld (L) Division was to move up on the left flank and take positions from west of the city to the Plyusa River.

West of the Plyusa, the 58th and 21st Infantry Divisions occupied the line. The two divisions had been ground down to about four understrength battalions. The history of the 21st reports that by the first days of February all the officers of the III/Grenadier Regiment 24 had been killed or wounded and that its companies were now commanded by sergeants.

Farther west the 12th Panzer and 126th Infantry Divisions would prepare for a counterattack from their positions east of Lake Peipus. Moving into their assigned positions proved extremely difficult for the German divisions. The 12th Panzer, fighting poor road conditions, was also hampered by roadblocks constructed by the many partisan units in the area.

58th Division Encircled

To the west, the Schleswig-Holstein troops of Siewert’s 58th Division met with disaster on February 9. As the 58th moved toward its positions on the flank of Reymann’s division it ran into Demidov’s 86th Guards Rifle and Burmistrov’s 224th Rifle Divisions, which were also moving up to take new positions. The Russians reacted quickly, engaging the Germans and splitting the division in two. By the next day the 58th had one of its regiments surrounded with the rest of the division trying to fight off the same fate. The 21st and 24th Divisions, which were supposed to occupy Siewert’s flanks, had not yet reached their positions, which left the 58th on its own. A German report stated:

“Russian forces filtered past [the 58th] on both sides…. The 24th Infantry Division got nowhere and for most of the day had trouble holding the Luga-Pskov railroad line.”

The 12th Panzer finally made it to its jump-off positions on February 10, but its attack stalled almost immediately as it ran into three Soviet rifle divisions (128th, 168th, and 196th). Although the 12th was able to escape encirclement, its attack was stopped dead in its tracks.

Things went from bad to worse for Model on the 11th. The entire 58th Division was now surrounded while the 24th and 21st Infantry Divisions were fighting for their lives as more Soviet units poured through gaps in the German line. Red Army troops also attacked westward, securing the small land area between Lake Pskov and Lake Peipus. A Schild und Schwert action was now impossible as the Eighteenth Army tottered on the brink of collapse.

Retreat From the Panther Line

During the evening of the 11th, Lindemann met with Model. He told his commander that the only way his army could survive was to further shorten the line, which would once again provide divisions to fill gaps in his defenses. Although Model initially balked at the suggestion, he reluctantly agreed to it. When he submitted the plan to OKH he was met with a stony silence that indicated Berlin would not even consider it.

At Narva the Soviets made another push that threatened the city, but the Germans held on. Hitler was worried that a Russian incursion into the Baltic States would result in Finland suing for peace. He promised reinforcements for the Narva sector, ordering the recently activated 20th SS Division, composed mostly of Estonians, into the line. To save the Narva sector, Lindemann was forced to send some units to help in Narva’s defense, which further weakened his own line. They included the battered 58th, which had managed to fight its way out of the encircling Russians, losing one third of its men in the process.

Even Berlin could not now ignore the calamitous situation that was occurring in Army Group North. Hitler finally understood that the army group could not possibly keep fighting the war of attrition that he had hoped would stop the Russians. Luga had already been abandoned on February 12, and several other important towns and cities were on the verge of falling. With German forces being forced to pull back all along the Eighteenth Army’s front, he gave approval for OKH to let Model give the order for a general retreat to the Panther Line on February 17.

Merging the Volkhov and Leningrad Fronts

Just days before, the Soviet command structure facing Army Group North had undergone a sweeping change when Stalin dissolved the Volkhov Front, giving its armies to Govorov’s Leningrad Front. Meretskov, over his objections to Stalin, was given command of the Karelia Front, which ran from the north shore of Lake Ladoga to the arctic coast west of Murmansk. The front had basically been static for almost two years—mostly due to the fact that the Finns had already regained the land lost after the 1939-1940 Winter War with the Soviets and had no wish to obtain any Russian territory.

It is interesting to note that it was Meretskov who presided over the disastrous 1939 winter campaign against the Finns that cost the Red Army more than 300,000 dead, wounded, and missing. For his failure Stalin downgraded him and put him in command of an army. He was replaced by Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko, who finally brought the Finns to the peace table.

Putting Govorov in charge of all armies facing most of Army Group North stretched Leningrad Front’s command and control to the limit. The vast forces under Govorov were fighting on a front stretching from Lake Ilmen to Narva. There was a great deal of staff work to be done to coordinate attacks by the various armies he commanded, and maintaining tight control on operations would continue to plague the Front.

The Sixteenth Army’s Fighting Retreat

As the Eighteenth Army was about to begin its withdrawal, the Sixteenth Army had to plan to lengthen its line to protect its left flank. The 2nd Baltic Front had been quiet for the past few days, but German aerial reconnaissance had discovered truck convoys of 2,000-3,000 vehicles each heading to the north and northeast. The 2nd Baltic Front was once more on the move.

On February 18, Popov’s 1st Shock Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Gennadi Petrovich Korotokov, hit German forces around Staraya Russa and forced the town’s evacuation. A combat group of Maj. Gen. Wilhelm Hasse’s 30th Infantry Division fought a desperate delaying action that slowed the Russian advance. Centered around Colonel Georg Kossmala’s Grenadier Regiment 6, the combat group exacted a heavy toll on the enemy in its fighting retreat. Kossmala was awarded the oak leaves to the Knight’s Cross for his actions in the battle, as well as for previous actions.

Hansen knew his right flank was also in danger due to the intelligence reports concerning the spotted convoys. It was time for him to withdraw the entire Sixteenth Army to the Panther Line, meaning some units, especially those on his left flank, would have to march as much as 300 kilometers to reach the position.

Kholm, which had been an important bulwark on the Lovat River, fell on February 21. On February 23, the city of Dno, the longtime headquarter site of the Sixteenth Army, came under attack by a joint assault from Maj. Gen. Pavel Anfinogenovich Stepanankov’s 14th Guards Rifle Corps (1st Shock Army) and Maj. Gen. Boris Aleksandrovich Rozhdestyenskii’s 111th Rifle Corps of the 54th Army. The first attack occurred late in the day and was repulsed by energetic counterattacks from Maj. Gen. Friederich Volcaker von Kirchensittenbach’s 8th Jäger Division, two security regiments, and a regiment from the 21st Feld (L) Division.

During the night several supply warehouses were blown up, and the city’s important rail hub was destroyed. The following day Colonel Vasilii Mitrofanovich Shatilov’s 182nd, Maj. Gen. Grigorii Semyonovich Kolchanov’s 288th, and Colonel I. A. Vorob’ev’s 44th Rifle Divisions took the city with the help of the 137th Rifle and the 16th and 37th Tank Brigades.

Completing the Withdrawal

As the Germans retreated, Kortokov was joined in the pursuit by Lt. Gen. Vasilii Nikitovich Iushkevich’s 22nd Army, which put even more pressure on the enemy. The 22nd was met by Laux’s II Army Corps, which put up a spirited defense while protecting X Army Corps’ southern flank. By using skillful delaying actions at various strongpoints, the Germans were able to prevent the Soviets from splitting Army Group North in two.

Model was further put to the test when Maj. Gen. Fedor Andreevich Zuev’s 79th Rifle Corps of Col. Gen. Nikandr Evlampievich Chibisov’s 3rd Shock Army appeared on the scene. Zuev was expected to exploit any gains made against Hoehne’s VIII Army Corps but was dramatically slowed by the stiff resistance displayed by Maj. Gen. Johannes Mayer’s 329th Infantry Division. Nevertheless, by February 26 Popov’s Front had pushed the Germans back from positions along the Dno-Novosokol’niki rail line.

Looking at the threats to Pskov and the Sixteenth Army’s right flank, Hitler ordered Model to speed up the withdrawal. The German forces still west of the Panther Line retreated skillfully. The race that began in January was finished by March 1, when the line was totally occupied. Although fighting along the Narva River continued, the Russians made little progress in that area. Along the rest of the Panther Line, both sides had shot their bolts, and by early March they were both in a defensive mode.

The Liberation of Leningrad

The Red Army had liberated the southern Leningrad region and had finally broken the blockade of the city. It had pushed the Germans back 200 kilometers or more in most places and had badly mauled Army Group North, but it had failed to encircle and destroy the Eighteenth Army. It also lost the race to the Panther Line. Had it succeeded, the road to the Baltic States would have been open, and German defensive lines farther south would have become worthless.

Assaults were always costly, especially at this stage of the war. The three Soviet Fronts involved from January 14 to March 1 suffered 76,886 killed, captured, or missing, and 237,267 sick or wounded out of the 822,000 troops taking part in the operation. Later attempts to pierce the Panther Line in March and April cost thousands more casualties.

The Germans would hold their positions in the north until the summer, when the Soviets attacked and decimated Army Group Center. The wholesale retreat of Army Group Center finally unhinged the Panther Line in the north, paving the way to a Russian advance through the Baltic States and into East Prussia.

last photo description is not correct. the description is for the first photo. last photo shows German soldiers, not Russion.