By Eric Niderost

On April 20, 1945, Adolf Hitler, Reich Chancellor and Führer of Germany, emerged from his underground bunker in the center of Berlin. The Third Reich was in its death throes, and Hitler’s presence in Berlin only seemed to prolong the agony. Actually, Hitler believed that his presence in the city would inspire the soldiers and civilians to fight on.

Germany was on its last legs, but Hitler refused to accept reality, stubbornly clinging to the notion that victory might still be achieved against the odds. In rare moments of lucidity, he candidly admitted the war was lost. “I am not going to leave Berlin,” he declared to his closest associates. “I will defend the city to the end…. Either I win the battle of Berlin or I die in Berlin. That is my irrevocable decision.” He also ranted and raged about how he had been “betrayed” by all around him.

Even at this late date Hitler couldn’t resist playing the warlord. April 20 was his 56th birthday, and on this special occasion a public appearance might bolster morale for the coming fight. Soviet armies—over two million soldiers—were even now in the process of encircling the beleaguered Nazi capital, and within a day or two Berlin would be completely cut off.

With artillery rumbling ever closer, a group of uniformed boys had assembled in the Reich Chancellery garden, where Hitler could greet them and personally award them Iron Crosses for bravery in combat. Most of them were teenagers, members of the Hitler Youth or the Jungvolk, a literally junior Nazi branch that was composed of 10- to 14-year-olds. German newsreel cameras from the Wochenschau film unit were on hand to record the ceremony, although so few theaters were still open that the viewing audience was bound to be small.

Hitler shuffled forward to the line of boys, a weak smile playing on his lips. For those who only knew him from earlier newsreels, postage stamps, or even propaganda photos, his appearance must have been shocking. At 56, he looked 30 years older, his face puffy and gray, his signature mustache streaked with white. He was wearing a military cap and an army greatcoat, the collar curiously turned up. The ailing Führer was hunched over, and his left hand shook uncontrollably, a symptom of advancing Parkinson’s disease.

Hitler spoke a few words to each boy, but his trembling hand prevented him from actually pinning the medals on their tunics. That job was done by Hitler Youth leader Arthur Axeman, who stood by Hitler’s side. And then Hitler came to the youngest soldier, a 12-year-old with the ironic name of Alfred Czech. After all, Hitler’s rape of Czechoslovakia had helped propel Europe into war.

Czech had rescued some wounded German soldiers under heavy Russian fire near his home in Goldenau, Silesia (now Poland). “So, you are the youngest of all!” a smiling Hitler remarked as he patted the young boy’s cheek. “Weren’t you afraid when you rescued the soldiers?” Czech, dazzled by the honor and Hitler’s presence, could only murmur, “No, my Führer!”

Then Hitler asked the boys if they wanted to go home or to the front. “To the front, my Führer!” they obediently cried. Even as the Reich crumbled around him, Hitler still exerted a certain power over the minds of many Germans.

Young Czech survived, but most of the other lads were later killed in battles with the Russians. The waste of young lives in an obscene cause was one of the great tragedies in these last days of the war. Hitler, blinded by his own delusional megalomania, said to the boys, “Despite the gravity of these times, I remain firmly convinced that we will achieve victory in this [Berlin] battle, and above all for Germany’s youth and you, my boys.”

It was going to take more than Hitler’s fanciful rhetoric to stop the Allies, particularly the encroaching Russians. In fact, the capture of Berlin was going to be a bone of contention among the Allied powers.

In March 1945, the British and Americans were advancing rapidly from the west. By April 1, the U.S. Ninth and Sixth Armies had completed their encirclement of the Ruhr, ultimately bagging 325,000 German soldiers. Farther south, General George S. Patton Jr.’s celebrated Third Army was pushing forward, an advance that would take it into Czechoslovakia and within 30 miles of Prague.

After eliminating the Ruhr pocket, the U.S. Ninth Army reached the banks of the Elbe River on April 11. Earlier, it had been decided that the Elbe would be the future demarcation line between the Western Allies and the Soviets. Nevertheless, the Americans initially didn’t let politics stand in the way of their advance. At Magdeburg the U.S. 2nd Armored Division created a bridgehead across the Elbe, and the U.S. 83rd Infantry Division established another at Barby.

American tank crews were certain that the Ninth Army would push on to Berlin, regardless of what Prensident Frankin D. Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, or anyone else had agreed to. The bridgehead across the Elbe was enlarged, until the Americans were at Tangmunde, a scant 50 miles from the German capital. General William H. Simpson, commander of the Ninth Army, asked General Omar Bradley for permission to go on to Berlin. The request was forwarded to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme commander of Allied Expeditionary Forces in Europe.

On paper, at least, it seemed very feasible. The only German force blocking the road to Berlin was General Walther Wenck’s Twelfth Army. Wenck, nicknamed “the boy general” because he was the youngest general in the Wehrmacht, was nevertheless competent and generally liked by his men.

His command, a fairly new formation, was a mixed bag typical of the late-war German Army. Wenck had young cadets, 16- and 17-year-old soldiers, and units of the RAD (Reichsarbeitdienst, or the State Labor Service). The RAD men performed similar functions for the German Army as the U.S. Navy’s “Seabees” did for the Marines and soldiers in the Pacific—building roads and fortifications and doing general construction work. In this crisis, they had to trade their shovels for rifles.

Perhaps even more telling was the fact Wenck had no tanks and virtually no air cover. He explained, “If the Americans attack they’ll crack our positions with ease. After all, what’s to stop them? There’s nothing between here and Berlin.” But in the end it wasn’t German resistance that stopped the American advance, but orders from Eisenhower himself.

General Eisenhower was reluctant to risk American lives for “prestige” or political purposes. There was also a concern that the Nazis might stage a last stand in southern Germany. It seemed best to mop up remaining resistance as soon as possible and end the war. Though Eisenhower had made the decision, not everyone agreed with it.

Winston Churchill was strongly in favor of the Western Allies taking Berlin ahead of the Russians. Earlier in the war Churchill cautiously welcomed the Russians, operating under the old adage “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” but the Red Army’s rapid advance into Eastern Europe was a cause for alarm. Churchill rightly feared that the Russians would set up puppet Communist regimes in the countries they liberated from the Germans.

The prime minister felt that the Anglo-Americans should go as far east as possible. Demarcation lines like the Elbe River could always be sorted out and renegotiated if necessary. Churchill expressed his concerns in a letter to Roosevelt. “If the Russians take Berlin,” Churchill explained, “will not their impression that they have been the overwhelming contributor to the common victory be unduly imprinted in their minds, and may this not lead them into a mood that will raise grave and formidable difficulties in the future?”

Eisenhower sent a personal message to Josef Stalin, telling the Communist dictator about the American intention to focus on southern Germany and asking him what the Russian plans were. Duplicitous as always, Stalin lied about the coming Soviet offensive. He agreed that Berlin had “lost its former strategic importance,” so the main Russian objective would be Dresden. Some “secondary” forces might start moving on Berlin, but in any event the offensive would probably begin in May.

Stalin’s assertions were in fact a pack of lies. Furtive, devious, and paranoid, always suspicious of people’s motives and intentions, the Soviet leader automatically assumed that the Western Allies were as treacherous as he was. Stalin was certain that Eisenhower’s message was a clever ruse and that the Allies were going to make a dash to Berlin in spite of American assurances.

In fact, Stalin had every intention of taking Berlin before the British and Americans. First, there was the question of national prestige and honor. The Russian people had suffered more than any other nation, with the possible exception of China. The figures are disputed, but the Soviet Union lost somewhere between 20 and 25 million dead during World War II. Perhaps five to seven million of these were military deaths, and the rest were civilians. After so much suffering the Russians felt they deserved to capture the ultimate prize.

Stalin also had other motives for seizing the German capital before the Allies could reach it. Though it was one of the most closely guarded secrets of World War II, Stalin’s spy network had uncovered information about the Manhattan Project, the American plan to develop an atomic bomb. In 1938, German scientists at Berlin’s Kaiser Wilhelm Institute had experimented with nuclear fission. Stalin hoped to get equipment, scientific data, and even a German scientist or two to help the Soviet Union’s own quest for a nuclear device.

This was an opportunity not to be missed because Stalin knew that the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute would be located in the future American occupation zone. On April 1, he summoned two of his top generals, Marshal Georgi Zhukov of the First Belorussian (sometimes called White Russian) Front and Marshal Ivan Konev of the First Ukrainian Front, for a conference. Originally, Stalin had promised that Zhukov would have the honor of capturing the Nazi capital. The Russian dictator was going to keep his options open.

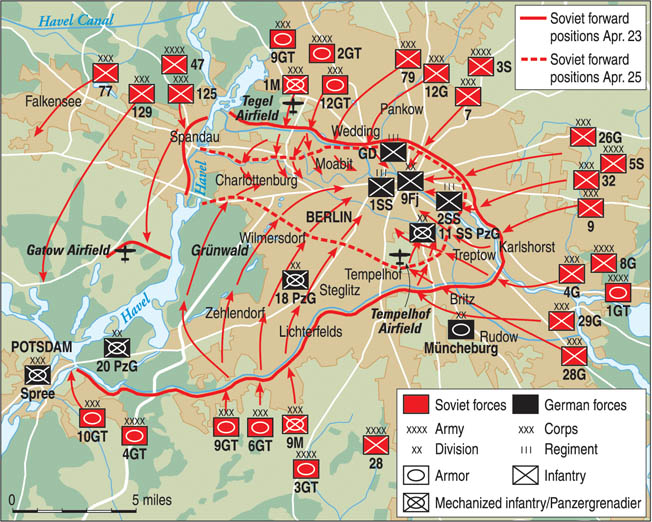

“Who is going to take Berlin? We or the Allies?” he asked the marshals. Stalin ordered each marshal to formulate his own attack plan and submit it within 48 hours. When their plans were finished, the marshals reported back to the Soviet leader for his approval. In general, Zhukov would launch an attack over the Oder River and take Berlin, while Konev would surround Army Group Vistula, secure Zhukov’s southern flank, and simultaneously push on to the Elbe. A third army group, the Second Belorussian Front under Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky, was to secure Zhukov’s northern flank by taking on German forces along the lower Oder River.

Stalin loved to stir up rivalries among his generals, which enabled him to exert more control over them. Drawing a pencil line on the situation map, Stalin designated each front’s movements to within 40 miles of the city. He also drew a demarcation line on the map, a boundary that was supposed to divide the two Russian army groups. Moving his hand steadily, he continued to draw the line until his pencil reached Lubben, just southeast of Berlin. He stopped drawing, leaving much of the south “open” and unmarked.

Not a word was spoken, but the message was loud and clear. If Konev could achieve a breakthrough, he would be permitted to capture Berlin from the south. The message was not lost on Zhukov either. He was more determined than ever to be the first into the capital of the Third Reich. Plans went ahead for the offensive, which was set for the early morning hours of April 16.

Marshal Zhukov was a hard-headed realist who knew that the capture of Berlin would not be as easy as some people thought. He later wrote, “Troops were expected to break through a deeply echeloned defense zone extending from the Oder River all the way to heavily fortified Berlin. Never before in the experience of warfare had we been called upon to capture a city as large and as heavily fortified as Berlin. Its total area was almost 350 square miles.”

While no pushover, Berlin’s defenses were not quite as formidable as Zhukov seemed to think. The city had been formally designated Fortress Berlin (“Festung Berlin”) in February, but planning had been confused, even chaotic, in the weeks that followed. The city had been divided into defense sectors, each with a designated letter from A to H. In addition, two concentric defense lines had been established, one roughly followed the city outline, while the other hugged the S Bahn (railroad line) that also encircled the great metropolis.

The inner, “last ditch” defense line protected the administrative district, where most of the government buildings such as the Reich Chancellery were located. The inner defense line centered on the island formed in the Spree River and the Landwehr Canal.

Berlin was also protected by three huge flak towers, the most notable being the Zoo Flak Tower in the Tiergarten. It was given this name because of its proximity to the world-famous Berlin Zoo.

The Zoo Flak Tower was actually composed for two ferro-concrete structures, Main Tower G and Tower L. The main tower was as high as a 13-story building and boasted walls 26 feet thick. Main Tower G looked like a castle keep, and indeed some of its functions paralleled its medieval counterpart. In the Middle Ages, the keep was usually the strongest and safest part of the castle. In similar fashion, the main tower was designed to accommodate 15,000 people during air raids. There was also a fully functional hospital within its concrete walls.

When all was said and done, the Zoo Flak Tower was primarily designed for the city’s defense. The tower’s roof had four twin mounts of 128 mm Flak 40s. The guns were loaded electronically, with gun crews loading ammunition into special hoppers. Some of the lower platforms featured 20mm and 37mm antiaircraft guns. The 350-man garrison had enough provisions to last a year.

When Allied bombing raids grew more intense, several thousand civilians crowded into the Zoo Flak Tower until living conditions became intolerable. The situation worsened when the Russians finally arrived. As many as 30,000 terrified Berliners crowded into quarters designed for half that number.

The Zoo Flak Tower also protected some archaeological treasures, including the 3,300-year-old bust of Queen Nefertiti that had been on display in the Egyptian Museum at Charlottenburg and the disassembled ancient Greek Altar of Zeus from Pergamon, removed from Berlin’s Pergamon Museum.

Berliners were a tough breed, determined to live as normally as possible. They would take trams to work, stoically ignoring the bomb craters in the streets and the wrecked, rubble-filled skeletons of buildings that arose on every side. Food was rationed, and scores of women would queue for even the most basic of items. The bombing was bad enough and shattered one’s nerves, but it was the Russian approach that was feared the most.

Berliners were being fed a constant diet of Russian atrocity tales, some true, some wildly exaggerated by Joseph Goebbels and the Propaganda Ministry. Stories of looting, rape, and murder of civilians were circulated almost every day. Nothing was said about what might have caused the Russians to behave in such a fashion. The Soviets wanted revenge, a payment in kind, for the terrible atrocities the German inflicted during four years of brutal war.

At times the fear of the Russians was almost palpable. Some of the terrorized citizens found relief in gallows humor. All around the city were signs that bore the legend LSR. It stood for Luftshutzraum, or “Air Raid Shelter,” but Berliners claimed the letters really stood for Lernt Schnell Russesch,” or “Learn Russian quickly.” But to most Berliners there was only one phrase that stood in high relief in their hearts and minds: “Bleib ubrig!” (“Survive!”).

German soldiers both inside and outside the city knew that the war was lost, but they continued to fight. There were two possible outcomes for a German soldier on the Eastern Front, death or capture. If captured, chances were that a soldier would end up a Stalinpferd, a “Stalin horse”—starved, beaten, and ultimately worked to death in a Siberian labor camp.

One German soldier explained how many in the Wehrmacht felt at that time. “We no longer fought for Hitler, or National Socialism, or for the Third Reich, or even for our finances or mothers or families trapped in bomb-ravaged towns. We fought from simple fear…. We fought for ourselves, so that we wouldn’t die in holes filled with mud and snow. We fought like rats.”

The Führer appointed General Helmuth Reymann to command of the city’s defense. Throughout the war, technically, Berlin had no garrison. There was the Berlin Guard Battalion, troops that had helped suppress the July 20, 1944, attempted coup against Hitler, but for “regular” troops Reymann only had some severely decimated German Army and Waffen-SS units, about 45,000 men in all.

Ironically, some of these men were not even Germans but were from all over Europe. There was, for example, the SS “Nordland” unit, composed mostly of Danes and Norwegians, but also an odd assortment of French, Hungarians, Romanians, and even some Swiss.

Whatever their origin, they proved to be some of Berlin’s best fighters. Most were fascist fanatics, to be sure, but they also fought with the courage of despair. They were turncoats and traitors to their countries, and they knew that, even if they survived the battle, they faced imprisonment or execution back home.

The regular troops were supplemented—if that was the word for it—by Volkssturm, Hitler Youth, and an odd assortment of city police and whoever else could be rounded up. The 40,000 Volkssturm were a mixed bag of older—sometimes really elderly men. Some had been soldiers, and some were veterans of World War I. Young boys of the Hitler Youth were also pressed into service, many of them around 14 years of age.

The city’s central administrative core, named “the citadel,” was a separate command. SS Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke, appointed by Hitler himself, took charge of this area. Mohnke commanded about 2,000 men, the core of which was the 800-man Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler Guard Battalion, the Führer’s personal bodyguard unit.

Later on April 20, right after the boys’ award ceremony, Hitler held a situation conference in his underground bunker. The bunker was a two-level complex made of reinforced concrete 50 feet below the ground. The upper story featured the kitchen, staff quarters, and living quarters for the Goebbels family.

The lower portion was the heart of the Führerbunker. There were 18 rooms, including Hitler’s bedroom, sitting room, and study. Eva Braun, Hitler’s secret mistress, occupied rooms right next to the Führer. A surgical suite, quarters for Hitler’s personal physician, and a guard room were also included. Perhaps the most important room was the telephone exchange, since it was the bunker’s link to the outside world.

The April 20 “birthday” conference was the last time that the Nazi hierarchy met together in one place. Most notable was Herman Göring, Reichsmarshal and head of the now largely defunct Luftwaffe. Others in attendance included SS Chief Heinrich Himmler, Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, Admiral Karl Dönitz, and architect and Armaments Minister Albert Speer.

When the group discussed the latest situation reports, it was clear that Germany was completely and irrevocably defeated, but Hitler still refused to accept reality, ordering nonexistent armies and divisions to come to the aid of the capital, shouting and screaming that he was surrounded by defeatists. Delusional as ever, Hitler announced that he was firmly convinced that the Russians would meet their “bloodiest” defeat at Berlin because of some last-minute “miracle” such as the sudden overwhelming influx of Speer’s top-secret “wonder weapons.”

Older than his years, ravished by overwork, stress, and Parkinson’s disease, he plainly wasn’t thinking clearly. Parkinson’s is a progressive, degenerative disease of the nervous system and can affect nerve cells in the brain. One symptom is a certain mental inflexibility.

Hitler’s health was also adversely affected by the injections he was given by his personal physician, Dr. Theodor Morell. Most members of the Führer’s entourage––even Eva Braun––felt Morell was an unprincipled quack, but Hitler depended on him. Morell pumped Hitler with a cocktail of 28 different drugs, either taken orally by pill or injection with a hypodermic needle. There were also vitamins, testosterone, an extract made of bull’s testicles, laxatives, sedatives, and opiates. Some injections were amphetamines, and the “anti-gas” pills Hitler swallowed actually contained strychnine.

Most of Hitler’s visitors found excuses to leave the city. Göring, for example, left to supposedly help organize the defense of southern Germany. It was all a transparent ruse, and Hitler wasn’t so far gone that he didn’t recognize what was going on. The symbolism was exact. The rats were leaving a sinking ship.

Colonel General Gottard Heinrici’s Army Group Vistula was Berlin’s principal field defense against the coming Russian assault. Heinrici had experience in fighting the Russians and was an expert in defensive warfare, but he knew he faced an impossible task, made worse by the fact that the Oder River “moat” had been breached and the Russians now had a bridgehead on the west bank at Kustrin.

In mid-April, Army Group Vistula had about 320,000 effectives, while the combined forces of Zhukov, Konev, and Rokossovsky had well over two million. There were two major formations in Army Group Vistula. The first was General Theodor Busse’s German Ninth Army, which occupied an area from the Finow Canal to Gruben—an area that included the all-important Seelow Heights. Busse had only 587 tanks, 55 of which were in repair and another 20 in transit.

The other major formation in Army Group Vistula was the aristocratic General Hasso Freiherr (Baron) von Manteuffel’s Third Panzer Army, on the Oder River to the north of the Ninth Army and stretched as far as Stettin. Manteuffel was also a short man, about five feet in height. A diminutive dynamo, he served with distinction in World War I and had a solid reputation as a panzer general.

Marshal Zhukov began his offensive to capture Berlin at precisely 4 am on April 16, 1945. The attack was preceded by the greatest artillery barrage ever experienced on the Eastern Front. Over 40,000 field guns, mortars, and Katyushka rocket launchers sprang to malevolent life, relentlessly pouring a heavy rain of explosives onto German positions. The Katyuska rockets, nicknamed “Stalin’s Pipe Organs,” were particularly feared by the Germans.

It was a barrage of apocalyptic proportions; the noise was deafening, while villages were pulverized and forests were set ablaze. The destruction was compounded by numerous sorties by the Soviet Air Force. It seemed that nothing living could survive such an onslaught, but Zhukov and his First Belorussian Front troops were in for a nasty surprise. Most of the shells landed in empty positions.

General Busse had anticipated a major Russian attack at the Seelow Heights, where the Berlin-Kustrin autobahn (highway) cuts through to the capital. Heinrici, ever the master of defensive warfare, knew exactly what to do. He abandoned the German forward positions, knowing they would be pulverized in the coming action. Instead he had his engineers fortify the crest of the heights, which rise about 150 feet and afford a great and commanding view of the Oder River area to the east.

But the wily general was not yet done. The Oder River’s floodplain was already quite soggy from the spring thaw of winter snow, but German engineers further flooded it by releasing water from a nearby swamp. The whole area in front of the heights became a morass, a swamp that would be a challenge for enemy tanks or any armored vehicles.

The hurricane of steel and fire ended after half an hour. It was time to launch the main assault. Col. Gen. Vasili Chuikov’s Eighth Guards Army was given the honor of spearheading the attack. It had been a long, hard road for the Eighth Guards, who had fought in the epic battle at Stalingrad. Now the prize—the “lair of the fascist beast” as one officer put it—seemed well within their grasp.

Russian women soldiers who were manning searchlights now turned them on, flooding the area with a blinding artificial illumination that created brightness of a hundred billion candlelight. The advancing T-34 tanks also turned on their headlights. The object, of course, was to blind the German defenders, but ironically many of the advancing Russians were blinded, too. A thin screen of dust and debris particles kicked up by the preceding barrage reflected light and made it hard for the Russians to see ahead.

The attack literally bogged down, the tanks finding the marshy ground almost too soft for their tracks. Slowed, they made tempting targets—almost sitting ducks—for the well-served German artillery, particularly the rightly feared 88, one of the best antitank guns of the war. Tank after tank was knocked out, but the Russian infantrymen pressed forward shouting their distinctive “Urrah!” cheers. Any T-34s that survived the 88s were taken out by fire from the panzerfaust—the German bazooka.

The Russian advance stalled, much to Zhukov’s embarrassment and chagrin. There was nothing left to do but press on, even at the cost of more and more casualties. Zhukov was even more upset by the realization that his rival Konev’s First Ukrainian Front was making good progress in the south. In fact, by the 17th Stalin was more than happy to give Konev the green light to swing around and take Berlin from the south. Even Rokossovsky’s Second White Russian Front, which was protecting Zhukov’s northern flank and taking on General von Manteuffel’s Third Panzer Army, was making slow, if steady, progress.

Manteuffel had his hands full but managed to fight on until April 25, when the Russians finally broke through. The fighting was so intense that some Russian soldiers found their way into Manteuffel’s headquarters where they managed to kill four of his staff and wounded four more. The general personally shot one Russian and dispatched another with a trench knife. Small but gutsy, von Manteuffel also risked his life doing reconnaissance flights in a Storch light airplane.

In the end nothing could stop Rokossovsky’s drive north. Manteuffel and what remained of his Third Panzer Army retreated to Mecklenburg to avoid annihilation. They later surrendered to the Americans.

Meanwhile, Konev’s advance in the south was so rapid it threatened the OKH command center in Zossen. General Hans Krebs, chief of the Army General Staff, was ordered to move the command center to a Luftwaffe air base not far from Potsdam. It was just in the nick of time because, not long after the German staff left, the Russians roared in on their tanks.

The “Ivans” could scarcely believe their eyes—there were two huge camouflaged complexes, Maybach I and Maybach II, with elaborate banks of telephones and teleprinters that could send and receive messages from far-flung Wehrmacht commands. This was the nerve center, the “brain” of the German Army and even as the Russians were shown around by an accommodating caretaker messages were coming in. The phone rang, and a Russian soldier answered it. On the other end of the line was a German general who asked, “What is happening there?” Bemused, the Russian said, “Ivan is here—go to Hell!”

Busse’s Ninth Army held out as long as it could, but it, too, had to give way. A portion of it fell back into Berlin, while the rest was surrounded and sealed off in a pocket in the Spree Forest; some soldiers managed to break out and surrender to the Americans. Once organized resistance was broken outside Berlin, it was only a matter of time before the Russians took the German capital.

The Seelow Heights defenders managed to hold for another two days, much to Zhukov’s frustration. The Russians, furious at the delays, attacked again and again with suicidal abandon. One German officer reported, “They come at us in hordes, in wave after wave, without regard to loss of life. We fire our machine guns often at point-blank range until they turn red hot. My men are fighting until they simply run out of ammunition. Then they are simply wiped out or completely overrun.”

There was nothing subtle about this kind of warfare. The Russians simply overwhelmed the defense by sheer weight of numbers. The Seelow Heights were finally taken on April 19, but not before the Russians lost an estimated 30,000 men and well over 700 tanks. But to Zhukov, it was worth it. There were a few scattered German units here and there, but essentially the road to Berlin was now wide open.

On April 20, Zhukov reported that the “long-range artillery of the 79th Rifle Corps of the 3rd Shock Army opened fire on Berlin. The guns were firing at extreme range and only the suburbs were hit.” The next day the 3rd Shock Army, 2nd Guards Tank Army, and 47th Army—all Zhukov formations—reached the outskirts of the city. The 1st and 2nd Guards Armies were given the “historic task to break into Berlin first and to raise the banner of victory.”

In essence two giant pincers—one from Zhukov, the other from Konev—were enveloping Berlin. Soon the pincers would become jaws, crushing and grinding the city between them. Hitler, still fantasizing, envisioned a counterattack that would involve SS Gruppenführer Felix Steiner and his Operational Group Steiner. In theory, Steiner and some other units would attack the northern pincers, but it came to nothing when Steiner reported that he simply did not have the men or equipment for such an attack.

By April 25, the trap was closed; Berlin was completely encircled by Zhukov and Konev. With the city cut off from the rest of the world, all pretense of normal life was abandoned. Postal service stopped, and the few remaining policemen were told to report to military units. Food became even scarcer, and most of the water mains were broken, creating acute shortages. Several million Berliners crowded into cellars or into the flak towers, where conditions went from bad to appalling, and waited for the end.

Sanitation became a problem when there was little or no water to be had. When the flush toilets became inoperable, the people crowded into the dank cellars used buckets. The stench from these makeshift chamber pots was unbearable, but to go outside was to risk death. There was no water to wash, so people wore the same dirty, sweaty clothes for days. Some people committed suicide in despair, and sometimes in all the chaos the bodies were not immediately removed.

Yet Berlin women once again showed an inner strength that was nothing short of amazing. As Russian shells began to hit the city, women in the food lines stubbornly refused to take cover. Food meant life, so it was worth the risk. It was said that a shell made a direct hit on a line of women while they patiently waited for rations. Those not immediately killed or wounded simply wiped the blood off their ration cards and reformed the shattered queue.

Fanatical SS units prowled for deserters, shooting or hanging suspects to provide an object lesson for others. As the Russians entered the suburbs and started encroaching on the city proper, the long-dreaded looting and rape began. German women tried to disguise themselves as men or purposely make their faces ugly, all to no avail. Young women and teens were special targets, but after a while virtually all women, even the elderly, were raped. Russian revenge would be complete.

Berlin was a city of broad avenues lined with 19th- and 20th-century apartment blocks. The German did have strongpoints, including turned-over trolley trams that were filled with rocks. Berliners didn’t think much of such defenses. They joked that it would take the Russians 21/2 hours to take the city—two hours of laughing their heads off and a half hour to break down the barriers.

In some respects the German defense was much more subtle. Snipers and machine guns were placed on upper floors because Russian tanks could not elevate their cannons high enough. Panzerfaust men were stationed in cellars to ambush unwary Soviet T-34s. At first Russian tanks went boldly down the centers of streets, but soon found they were sitting ducks if they used this method. They soon learned to hug the sides of the streets.

Colonel General Chuikov of the Eighth Guards Army wrote out some general assault guidelines that proved to be very effective. Small assault groups of seven or eight men armed with grenades, submachine guns, daggers, and sharpened spades would be the first to move forward. They would be backed up by reinforcement units that were heavily armed with machine guns and antitank weapons.

Since fighting was often from house to house and room to room, Russian sappers were on hand with pick axes and explosives to blast or bore though walls if necessary. German defenders often countered by throwing grenades into newly opened holes in the walls. Russian artillery was also employed to pound resisting buildings into rubble. The fighting was brutal and bloody, and many civilians were killed as they cowered in cellars, attics, and other hiding places.

On April 25, Hitler appointed General Helmuth Weidling as the new commander of “Fortress Berlin.” Weidling’s 56th Panzer Corps had been part of Army Group Vistula, and the general took what remained of his men back to Berlin after the Russian breakthrough. Initially, Hitler thought of executing Weidling because he had retreated in the face of the enemy but then relented and gave the surprised general his new command.

Weidling accepted the assignment, but an inspection tour was anything but encouraging. As he remarked, “The Potsdamer Platz and Leipzigerstrasse were under strong artillery fire. The dust from the rubble hung in the air like a thick fog … shells burst all around us. We were covered with bits of broken stones. The roads were riddled with shell craters and piles of brick rubble.”

The general devised a plan for Hitler to break out of Berlin before it was too late, but the Führer rejected it out of hand. “I don’t want to be wandering in the woods,” an irate Hitler told his new commander. He intended to stay “at the head of his men” and die in Berlin. The general was cautioned, however, to continue the defense as vigorously as possible.

Hitler still had one hope. If General Wenck’s Twelfth Army could disengage from the Western Front, it might be able to save Berlin from the Russian hordes. For a time it looked as if Wenck was indeed a miracle worker. His weary troops disengaged, turned around, and moved toward Berlin. The Russians, not expecting an attack from this quarter, were thrown off balance, and Wenck’s men did make some progress.

The Twelfth Army got close to the city but was finally halted at Potsdam. When he found he couldn’t break through, Wenck wisely did the next best thing. He fought hard to keep a corridor open to the west so that civilian refugees and scattered German units could take refuge or surrender to the Americans. For several days Hitler was always asking, “Where’s Wenck?”

The fighting raged on, and soon the Russians were approaching the citadel, or Government District. A Russian war correspondent, Lt. Col. Pavel Troyanovski, wrote, “Our guns sometimes fired a thousand shells into one small square, a group of houses, or even a tiny garden. The German firing points would be silenced, and the infantry would go into the attack.… At the height of the street fighting, Berlin was without water, without light, without landing fields, without radios stations. The city ceased to resemble Berlin.”

Meanwhile, Heinrici’s Army Vistula Group was being reduced to irrelevancy, and the general, who realistically viewed the war as lost, pleaded with his superiors to declare Berlin an open city so that the civilians could escape. But the Nazi leadership would have none of it and, on April 28, after Soviet forces had broken through at Prenzlau, Heinrici was relieved of command.

By April 29 the Government District was completely surrounded by Soviet forces, but the Eighth Guards Army in the Tiergarten and the 3rd Shock Army were held back by accurate fire from the Zoo Flak Tower. The gunners there were assisted by Hitler Youth, who were lending a hand even though they were not officially assigned to that position.

The 13-story tower afforded a panoramic view of Berlin, but the sweating German flak crews were too busy to pause and gaze at the view. Perhaps it was just as well. A German colonel named Wohlermann did have a look, and what he saw chilled him to the bone. There, spread out before him, was a vision of hell that would have tested even the powers of a Dante to describe. The colonel recalled later, “One had a panoramic view of the burning, smoldering, and smoking great city, a sight that shook one to the core.”

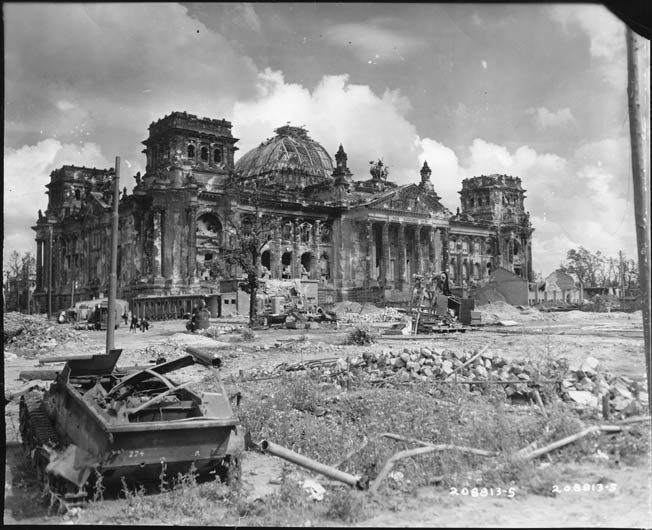

The Government District included Hitler’s Reich Chancellery, the Ministry of the Interior Building, the Kroll Opera House, and the most important symbol of all, the Reichstag or German Parliament building. Many of these structures were built around a large plaza called the Königsplatz, with the 220-foot Siegessäule (Victory Column) its centerpoint. Even in its battered condition, the Reichstag was an imposing structure, but had not been used since a mysterious fire had raged there in 1933.

The Reichstag had been turned into an Alamo, manned by about 5,000 stubborn defenders. The lower stories had been reinforced with concrete steel rails and all windows and doors had been bricked up and then pierced by loopholes. A water-filled antitank ditch fronted the building, and all the roads leading to the Reichstag and the Königsplatz were mined. With the Reichstag sheltered in the loop of the meandering Spree River, some German 88mm guns in the Königsplatz covered the Moltke Bridge, one of the spans across the Spree.

The Russians crossed over the Moltke Bridge and took the Interior Ministry after some hard fighting. The Russians nicknamed the Interior Ministry “Himmler’s house,” because that is where the headquarters of the Gestapo was located.

On the morning of April 30, Maj. Gen. Perevertkin of the 79th Rifle Corps was given orders to take the Reichstag by storm. This was a great honor, and it is worth noting that the 79th Rifle Corps was part of the 3rd Shock Army—one of the units under Marshal Zhukov, who had bested his rival Konev.

The 79th Rifle Corps’ attacks on the morning of April 30 were in two phases. One at 4:30 am and a second at 11:30 am were repulsed by heavy German small-arms fire. After unleashing an artillery barrage on the building, the Russians surged forward yet again. This time they broke into the Reichstag, but the fighting was not over. The German defenders used everything they had—grenades, pistols, machine guns, and panzerfausts within the shattered rooms and halls. The struggle was bloody and merciless.

German guns became red hot and useless from continued firing. Every room, every foot of ground was fiercely contested. The last defenders, trapped in a basement, held out until May 2. But for all intents and purposes, the Reichstag was taken on April 30. Russian soldiers climbed to the roof and displayed the crimson Communist banner of the Soviet Union. Later, when the flag raising was recreated for newsreel cameras, it became one of the iconic images of World War II. About half the Reichstag defenders were killed, and the rest were taken prisoner.

By this time, however, Adolf Hitler, fearing Russian capture, was dead, having committed suicide on the afternoon of April 30. First he had his dog Blondi poisoned, then he and Eva Braun, whom he had married less than 40 hours earlier in a ceremony in the bunker, closed the door to his quarters. Aides heard a shot and then entered to find their Führer dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head; his bride was sprawled on the sofa next to him. She had taken cyanide. The bodies were carried upstairs to the courtyard of the bunker and set on fire.

Before he died, Hitler had named Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels the new chancellor. Nazi fanatic though he was, even Goebbels recognized that further fighting was pointless. He sent General Krebs, who spoke Russian, to General Chuikov of the Eighth Guards Army at Schluenburgring near Templehof airport to negotiate an end to the fighting.

The meeting took place on May 1 at 4 am. Krebs was authorized to negotiate a ceasefire, truce, or armistice, but the Russians would have none of it—it was unconditional surrender or nothing. Krebs came back empty handed, and he later committed suicide in the bunker. Chuikov had lost patience with all the wrangling. “Pour on the shells,” he ordered. “No more talking.”

By this time, Goebbels was also dead, having killed himself while his wife poisoned their children and took her own life the day after Hitler’s suicide. Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz (who was not in Berlin) was named Reich President, Head of State, and Commander in Chief of the German Armed Forces.

It fell to General Weidling to finally surrender what was left of the German defenders. He was taken to General Chuikov’s headquarters at 6 am on May 2. Once the capitulation was signed, Weidling ordered all remaining German units to “cease resistance forthwith.”

All across Berlin dazed German defenders emerged from the rubble, hands held high. On May 2, 1945, at 3 pm, the battle of Berlin was officially over. Elsewhere in Germany a few pockets of resistance held out. Breslau, for example, did not surrender until May 6.

The Russian guns stopped firing, creating what one historian called “a great enveloping silence.” But the agony of defeat was not yet finished. Around 125,000 Berliners had died during the siege, many by suicide.

Once the shelling had stopped and the Soviets entered Berlin, a great wave of sexual assault swept across the city. Some German women killed themselves after being raped. Other victims—aged 12 to 70—were killed outright, sometimes being shot or having their throats cut after being ravaged by the victors.

One 17-year-old German girl’s experience was typical: “There were eight Russians…. I was incredibly afraid…. They tore the clothes from my body…. I screamed but afterward I had no tears anymore … then I thought how many more are still coming, and then I thought when this is over then there will be a shot in the back of the head.” Somehow she survived the ordeal.

Berlin was a silent, smoldering ruin, its buildings mere hollow shells, its streets filled with craters, debris, and corpses. There were no city services; water, food, and electricity were all but nonexistent.

The victorious Russians had at last gotten their revenge, but at a heavy cost. Between April 16 and May 8 (the official end of the war in Europe), Zhukov and Konev lost 304,887 killed, wounded, and missing—about 10 percent of their combined strength.

The fall of Berlin was also the fall of the Third Reich.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments