By Nathan N. Prefer

They had been staring at it for the past four months. That small, rubble-strewn town of Cisterna di Littoria in central Italy just inland from the ports of Anzio-Nettuno, had become their nemesis. They had fought over it before and been defeated. It had cost them two battalions of the 6615th Ranger Force (Darby’s Rangers) and many others. It had been bombed, shelled, and strafed, but it was still defended tenaciously by the German Army. If anything, it symbolized the frustrations of the men of the American VI Corps.

The VI Corps, part of the Fifth U.S. Army, had come ashore in Italy at Anzio on January 22, 1944. After establishing a beachhead against minimal opposition, the troops had begun an advance inland with the objective of outflanking the German army defending the Cassino front miles to the south. There the German Tenth Army had been holding back the Fifth Army and Eighth British Army, which were attempting to clear southern Italy and capture Rome. The VI Corps mission was to compromise the German defenses of the Gustav Line and force the enemy to withdraw or surrender.

It did not work out as planned. After spending a week organizing the beachhead, the VI Corps commander ordered an advance to the Alban Hills, which overlooked the main highway in use by the Germans. But the German Army was much faster, and troops from all over northern Italy, southern Germany, and the Balkans had been rushed to the Anzio area. By the time VI Corps received orders to advance, an entirely new German army, the Fourteenth, was surrounding it. Allied intelligence failed to discover the existence of this new army before the attack was launched on January 29, 1944.

The attack centered on Cisterna, a small town that happened to be the hub of several roads running east and north, directions in which VI Corps needed to go to cut the German lines of communication and reach Rome. A railroad also ran northeast from Cisterna. The plan was for Colonel William O. Darby to infiltrate his 1st and 3rd Ranger Battalions through the German lines at night. At daybreak the remaining battalion, the 4th, would lead the 3rd Infantry Division in an attack to capture Cisterna and advance east. A few tanks from the 751st Tank Battalion and a platoon of the 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion were in reserve.

The infiltration began at 0100 hours on January 30, 1944, and soon developed into a disaster. Initially, however, it went as planned. Using a long drainage ditch, the two infiltrating Ranger battalions moved deep into the German lines. But when the ditch ended the Rangers were forced into the open along the Feminamorta-Cisterna road. Soon a German sentry gave the alarm, and within moments the two battalions were fighting for their lives. Fighting off tanks and infantry supported by machine guns, mortars, and artillery, the lightly armed Rangers were outgunned. Frantic efforts by the 4th Ranger Battalion to relieve them, even when supported by tanks and artillery, failed. When it was over later that day, some 12 Rangers had been killed, 36 wounded, and 743 captured. In attempting to reach their brother Rangers, the 4th Ranger Battalion suffered 30 killed and 58 wounded. The battle marked the end of “Darby’s Rangers.”

Cisterna remained unreachable by the Americans for the next four months. A ferocious German counterattack designed to destroy the British-American beachhead failed only by a thread. The American and British lines were pushed back in some places to the “Final Beachhead Line” after which evacuation or surrender would be the only choice left to VI Corps. But the Allies prevailed, despite crippling losses suffered by the 45th Infantry Division and the 1st British Infantry Division. A stalemate ensued beginning at the end of February 1944 and lasted into May.

Things had changed by May 1944. The Allies had more troops and equipment available on both the Cassino and Anzio fronts. The weather was improving, allowing Allied air power to make its presence felt. Lt. Gen. Mark Wayne Clark, commanding Fifth Army, which included VI Corps at Anzio, was ordered to implement a plan to break through the German defenses. Known as Operation Diadem, it included attacks against the Gustav Line and a breakthrough at Cassino after which the VI Corps would launch a massive attack, hoping to cut off the retreating Tenth Army.

Once again the focus of any breakout from the Anzio beachhead was Cisterna. Control of the roads and railroad leading north to Rome and east across the German lines of communication was essential to a successful breakout.

The Germans had not been idle. A major regrouping of their forces began in March with the arrival of a fresh Jäger division from the Adriatic coast. Five German divisions divided into two corps faced VI Corps at Anzio. The I Parachute Corps controlled the 4th Parachute Division, 65th Infantry Division, and 3rd Panzergrenadier Division. The LXXVI Panzer Corps included the 362nd and 715th Infantry Divisions. In all, Col. Gen. Eberhard von Mackensen’s Fourteenth Army had 70,400 men facing the approximately 90,000 Allied troops at Anzio.

The VI Corps, now commanded by Lt. Gen. Lucian King Truscott, Jr., who had replaced Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas, was different as well. Of the many units that had fought at Anzio since January, most were still there. New arrivals included the veteran 34th Infantry Division and remaining elements of the 1st Armored Division. Along the British sector of the corps front, the exhausted 56th Infantry Division had been replaced by the 5th British Infantry Division. The veteran 1st British Infantry Division remained, but one of its brigades was replaced due to its earlier heavy losses.

Selected for the assault force for the breakout battle were the veteran 1st Armored Division, 3rd Infantry Division, and the Canadian-American 1st Special Service Force, also known as the “Devil’s Brigade.” The 34th Infantry Division relieved the 3rd Infantry Division along the front lines on March 28, 1944, to allow it to train replacements and prepare for the coming battle. It would also attach one of its infantry regiments to the 1st Armored Division, which under a new table of organization was short of infantrymen for the type of battle to come. The 45th Infantry Division, 1st Special Service Force, and 36th Engineer Combat Regiment would hold the front lines and protect the flanks of the main attack. The 36th Infantry Division, which had only arrived on the beachhead on May 22, would be the corps reserve force.

Major General Ernest Nason Harmon commanded the 1st Armored Division. Born February 26, 1894, in Lowell, Massachusetts, he was commissioned in the cavalry from West Point in 1917. He served in France during World War I and in a number of prestigious staff and instructor appointments between the wars. General Harmon’s decorations included the Distinguished Service Cross, two Silver Stars, the Bronze Star, and a Purple Heart. Promoted to major general in August 1942, he commanded the 2nd Armored Division until transferred to the 1st Armored Division in 1943, after seeing significant combat in North Africa and Sicily.

General Harmon had a plan for his attack that involved “snakes.” One of the known main obstacles to breaking the German defenses in front of Cisterna was the existence of mines. Literally thousands of them lay buried between the American and German front lines.

Harmon’s engineers came up with “snakes,” 400-foot-long steel pipes filled with explosives that were towed into position by tanks and then set off by machine-gun fire, to detonate the hidden mines. Tests showed that these devices would clear a 15-foot-wide gap in any minefield. Enemy mines buried as deep as five feet were detonated. The problem was that the long pipes were unwieldy and could not be towed for any great distance. Harmon left the decision to use or not use them up to two subordinate commanders. Colonel Maurice W. Daniel, leading Combat Command A (CCA), decided to use them. Brig. Gen. Frank Allen, Jr., commanding Combat Command B (CCB), held his in reserve in anticipation of stronger minefields farther along his route near the railroad running northwest from Cisterna

Attacking Cisterna directly was the veteran 3rd Infantry Division. Its commander, Maj. Gen. John Wilson “Iron Mike” O’Daniel, was born in Newark, Delaware, on February 15, 1894, and served in the Delaware National Guard before graduating from Delaware College. Commissioned in the infantry in 1917, he served in France during World War I. General O’Daniel had been the assistant commander of the 3rd Division before assuming command in February 1944, when General Truscott was promoted to VI Corps command. Among his decorations were the Distinguished Service Cross, two Silver Stars, four Bronze Stars, two Air Medals, and a Purple Heart. General O’Daniel planned to use all three of his infantry regiments abreast to seize Cisterna.

The attack began with a diversionary thrust by the 1st and 5th British Infantry Divisions on the beachhead’s left flank. Preceded by a heavy artillery barrage, the two British divisions attacked during the night of May 22, 1944, against the I Parachute Corps, in an effort to draw German attention to that area of the beachhead. The British kept up their diversionary attack for 24 hours before returning to their starting positions.

The first direct blow at Cisterna came by chance. The diversionary attack was to be supported by a heavy artillery barrage and air support by some 60 fighter bombers of XII Tactical Air Command. But heavy overcast obscured the German front lines, and the aircraft moved to the secondary target, Cisterna. The town was left burning and battered.

With the 135th Infantry Regiment, 34th Division attached, the 1st Armored Division attacked an hour after first light on May 23, 1944. CCA, attacking west of Le Mole Creek, found the terrain fairly even and slightly rising at first but soon came upon a series of creeks and draws that slowed progress. The snakes cleared not only the minefields, but when used close enough to German strongpoints knocked the defenders unconscious or so dazed them as to make them unable to resist. Daniel’s tanks rolled forward, leaving the infantry to mop up bypassed enemy positions. By noon, CCA was approaching the railroad.

Attacking to the east of Le Mole Creek, General Allen’s CCB had less luck. Like CCA, CCB included a battalion of medium tanks, two battalions of infantry, a battalion of light tanks, and two companies of tank destroyers as the assault force. A battalion of infantry and a battalion of medium tanks were kept in reserve. But Allen had opted not to use the snakes. To further complicate his situation, friendly minefields had not been properly marked due largely to confusion when the 34th Division had relieved the 3rd Division.

Within minutes of beginning its advance, Company D, 13th Armored Regiment was out of the fight, and Company E had to assume the assault mission. To help replace the heavy losses, a platoon of Company B, 701st Tank Destroyer Battalion was added to the assault force. The 3rd Battalion, 6th Armored Infantry, however, followed the tank tracks through the minefields and managed to maintain the advance while behind them Company C, 16th Armored Engineer Battalion cleared the mines by hand. Continuing forward, CCB brushed aside moderate resistance and reached the railroad by midday.

A hasty German counterattack, probably by the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division, against the flank of the attack forced American infantry to give ground. But a strong artillery barrage and an appearance by Combat Command Reserve (CCR) under Colonel Hamilton H. Howze repulsed this attempt to stall the American breakout.

It was during these attacks that Technical Sergeant Ernest H. Dervishian of the attached 135th Infantry distinguished himself. He and four members of his platoon found themselves well in advance of the supporting armor. Enemy artillery and sniper fire covered the area as the Richmond, Virginia, native led his men toward a railroad embankment. Spotting several enemy soldiers in a nearby dugout, Sergeant Dervishian ordered his men to provide covering fire. He attacked the Germans with his M-1 carbine, forcing their surrender. His men then captured 15 more enemy soldiers in nearby dugouts.

After sending his prisoners to the rear, Dervishian saw nine Germans fleeing across a ridge. His fire wounded three of the enemy, and the sergeant dashed forward alone to capture the rest. Four more men arrived, and Dervishian sent them to protect his flank. These new men were driven back by heavy enemy machine-gun fire. One of his men was killed and another wounded. German grenades began falling nearby. Ordering his men to withdraw, Dervishian attacked the gun alone, captured it, and then turned it on a second enemy machine gun. Seeing movement in a nearby dugout, Dervishian grabbed a German machine pistol and began firing both machine gun and machine pistol at the two different enemy positions. Quickly, five German soldiers in each of the two positions surrendered. Turning over the prisoners to his men, Dervishian continued on alone, knocking out a third enemy machine gun before returning to his platoon. For his leadership and gallantry on May 23, 1944, Sergeant Dervishian was promoted to second lieutenant and awarded the Medal of Honor.

Not far away, Staff Sergeant George J. Hall, also of the attached 135th Infantry Regiment, was with his company as it advanced across the level terrain. Three enemy machine guns and several snipers opened fire, pinning the Americans to the ground. Volunteering, he crawled forward through this murderous fire until he reached a position within hand grenade range of the first enemy gun. Tossing four grenades in quick succession, he knocked out the gun and crew. Four prisoners were ordered to crawl to American lines while Hall continued on alone. Seizing a supply of German grenades found in the machine-gun position, he repeated his exploit at the next enemy post, all the while under direct machine-gun and sniper fire. After five of their comrades fell to Hall’s borrowed grenades, the remaining five Germans surrendered. Sending his prisoners back, Sergeant Hall began an advance on the third enemy gun. As he did so an enemy artillery barrage hit the area, severing his right leg.

Although suffering excruciating pain, he tried to crawl the 75 yards back to his company. The pain was unbearable. “I lay there and rested a while and gathered my wits,” he said later. “I was still under fire and I knew I’d have to do something. I studied it for a while and then pulled my sheath knife and cut through two tendons that were holding my right leg on. I was able to crawl after that.”

With two enemy guns knocked out, Hall’s company was now able to maneuver and knock out the remaining gun. Sergeant Hall died several days after the action and received a posthumous Medal of Honor.

The enemy minefields continued to present a problem, however. When two infantry platoons supporting the armored attack became disorganized, 2nd Lt. Thomas W. Fowler, a tank platoon commander, stepped forward and earned the Medal of Honor. The officer from Wichita Falls, Texas, took charge and reorganized the tank-infantry assault. He then made a personal reconnaissance through the minefield, clearing a path as he went. Subsequently, he returned to the infantrymen and led them through the field a squad at a time.

Under enemy small arms fire he then went ahead alone to find a route for the infantrymen to their objective and led several tanks through the same minefield. When the two infantry platoons came to their objective, Fowler led the attack, personally capturing several Germans. Seeing a dangerous gap between his unit and its neighbors, he again led the way and placed the infantry in a better tactical position. Returning to his tanks under heavy mortar, small arms, and artillery fire, he brought them forward.

German tanks counterattacked, hitting one of Fowler’s tanks and setting it afire. Without regard for his personal safety, Fowler tried to rescue the crew of the burning vehicle. Only when the enemy tanks were about to overrun him did he retreat a short distance, where he began treating at least nine wounded infantrymen. Fowler was later killed in action and was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor.

In total, 11 Medals of Honor would be awarded to American soldiers who made the Anzio beachhead breakout possible. At the end of the first day, the 1st Armored Division had achieved its initial objective at a cost of 35 killed, 137 wounded, and one missing in action. The attack had pierced the German main line of resistance and pushed the 362nd Infantry Division back a mile. The penetration threatened the junction between the Fourteenth Army’s I Parachute and LXXVI Panzer Corps.

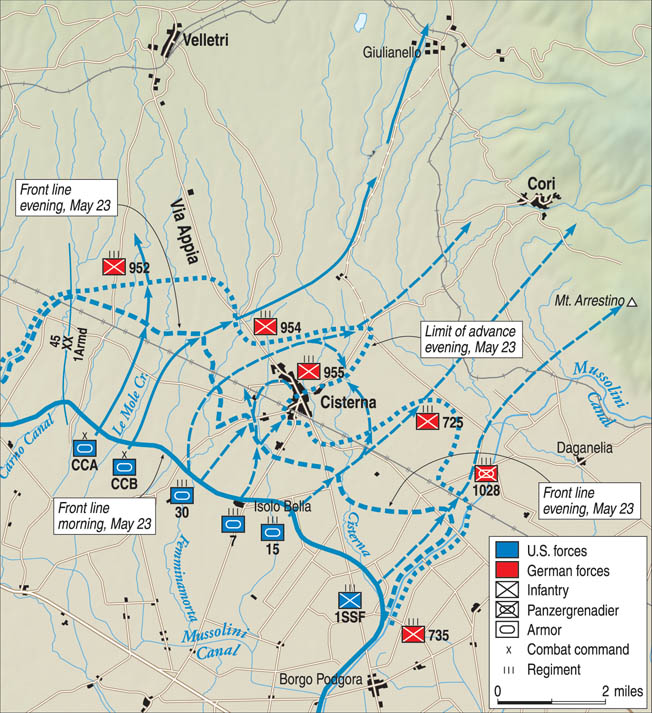

In the four months since it landed at Anzio on January 22, 1944, the 3rd Infantry Division had suffered 1,074 killed, 4,302 wounded, and 919 missing by the time of the May attack. An additional 6,455 men had been lost due to non-battle causes. General O’Daniel’s plan of attack placed the 30th Infantry Regiment on the left, the 7th Infantry Regiment in the center, and the 15th Infantry Regiment on the right. The idea was that the center regiment would hold the Germans at Cisterna in place while the two flanking regiments encircled the town. They would be facing the 955th Infantry Regiment of the 362nd Infantry Division and elements of the 715th Infantry Division. Reinforcing the front was the 1028th Panzergrenadier Regiment. Intelligence estimated the division faced four enemy battalions on the front lines with three more in reserve. As in the 1st Armored Division’s zone, mines would be a serious threat.

Colonel Richard G. Thomas, commanding the 15th Infantry Regiment, had an additional problem. His orders required him to wheel inward after bypassing Cisterna to complete the planned encirclement. But that would turn him away from his right flank neighbor, the 1st Special Service Force. To avoid leaving a dangerous gap that might be exploited by the enemy, he created a special task force commanded by Major Michael Paulick around Company A, a platoon of medium and light tanks from the 751st Tank Battalion, and a section from the 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion. Reinforced with machine guns, mortars, and engineers, this task force was to cross the Cisterna Canal and drive east to cut Highway 7, blocking any enemy interference with the main attack.

Like General Harmon, General O’Daniel was anxious to find some way to reduce his casualties in the attack. The 3rd Infantry Division came up with the “battle sled,” an open-topped narrow steel tube mounted on flat runners and wide enough to carry one infantryman in a prone position. The battle sled served as protection against shell fragments and small-arms fire and was used to transport infantrymen through enemy fire in what were perceived as portable foxholes. A battle sled team of 60 men had been organized in each of the division’s three regiments. Five tanks towed 12 sleds. Unfortunately, this experiment came to naught when drainage ditches forced the infantry to continue the advance on foot.

The attack of the 30th Infantry hit strong resistance from the beginning. Colonel Lionel C. McGarr’s regiment faced small arms fire, self-propelled guns, and artillery even before it crossed the line of departure. Yet the attack made progress. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions bypassed enemy strongpoints to maintain the momentum of the advance. Company I actually reached its objective at Ponte Rotto ahead of schedule. But it was pinned down by both enemy and friendly fire. American artillery hit the area, and the company had lost radio contact with the rear.

After about 30 minutes Staff Sergeant Cleo A. Toothman, a squad leader, heard one of his men, Pfc. John Dutko, yell, “Toothman, I’m going to get that 88 with my heater!” Toothman added, “He always called his BAR a ‘heater.’” Pfc. Dutko then raced 500 yards through heavy fire as machine-gun bullets followed him in the dirt. The German 88mm gun also fired, but he kept moving. Diving into a convenient shell hole, Dutko took a short rest.

He jumped out of the hole and again raced for the enemy gun.

This time Pfc. Charles R. Kelley followed him. Dutko meanwhile raced ahead so that only one enemy machine gun could track him. He attacked this gun with grenades and knocked it out. Then he stood erect and began walking toward the 88mm gun, firing his BAR from the hip. After killing the five-man crew, Dutko wheeled around and killed the crew of a second machine gun. The third gun, however, opened fire. Dutko was wounded but managed to kill the crew of the third machine gun before falling dead across the position. Dutko received a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Company E also ran into trouble near Ponte Rotto. Enemy machine-gun fire cut down four men and pinned down the rest. “Pfc. Patrick L. Kessler, an antitank grenadier in my platoon,” recalled Pfc. Nicholas Rusinko, “ran 50 yards through a hail of machine-gun fire to a point where three of us were huddled in a ditch and suggested that we form an assault team to knock out the gun, which we instantly agreed to. Using us as a base of fire, Pfc. Kessler climbed out of the ditch and began to crawl toward the machine-gun position. He succeeded in making his way about 50 yards forward before the Krauts spotted him and fired directly at him. Bullets struck so close to him that Kessler was almost obscured by the dust. Later I learned that he had been lightly wounded.”

Charging like a broken-field runner, Kessler got to within two yards of the enemy position, kneeled down, and shot the gun crew with his Springfield M1903 bolt-action rifle. As he sent prisoners to the rear two more enemy guns and several riflemen opened fire on the company from about 175 yards away. Ten men who had stood up after Kessler knocked out the first gun were cut down. Kessler crawled to a nearby BAR man, acquired his weapon, and began crawling through a minefield toward the enemy.

Private Alan C. Smith saw what happened next. “Just as he crawled out of the minefield, Pfc. Kessler occupied a position in a ditch about 50 yards from the Kraut strongpoint and engaged in a duel with the two machine guns. Throughout this action, the German artillery and mortar fire kept coming in. Pfc. Kessler had fired about four magazines into the Krauts when an artillery shell landed almost directly on top of him. For a moment we all thought that his number was up, yet when the smoke had cleared away, Pfc. Kessler had risen to his feet and was walking toward the machine guns, firing his BAR from his hip as he advanced.”

After knocking out the two guns and taking 13 prisoners, Kessler was escorting the prisoners to the rear when two enemy snipers opened fire on him. His prisoners made a break for it, but before they could get far Kessler fired a BAR burst on either side of them, halting the escape attempt. With his prisoners under control, Kessler opened fire on the snipers, both of whom quickly surrendered to him. Kessler was later killed and received a posthumous Medal of Honor.

The 7th Infantry struggled. Enemy artillery fire delayed its start for 20 minutes. Tanks were lost to mines. General O’Daniel ordered additional smoke cover and supporting artillery, and soon the 7th Infantry began to make progress. Small German tank-led counterattacks also slowed the advance, but these were soon driven back. The 7th Infantry’s frontal attack on Cisterna ground forward slowly, halted by an enemy strongpoint near a locale known as Isola Bella. An attempt to bypass the strongpoint failed, and a frontal attack cost several more casualties. In attacking beyond Isola Bella, Company K lost two commanders killed in the space of a few hours. The Germans had the advantage of higher ground and prepared defenses.

The 15th Infantry Regiment was to bypass Cisterna on the southeast and seize Highway 7 and the railroad. The plan called for two battalions to attack with a third in reserve. Resistance was stronger than expected and the ground to cover more extensive, so all three battalions were soon attacking while Major Paulick’s task force struggled to maintain contact with the 1st Special Service Force. During the attack, Company L, which began the assault with 150 men, found only about 40 available for duty at the end of the first three hours. The survivors were attached to Company I.

Infantrymen carried forward on the battle sleds were able to make some progress supported by the tanks that had pulled them. Company E, low on ammunition after struggling forward, launched a successful bayonet attack that cleared a German strongpoint. Company G bypassed some resistance and began to clean out the small town of Fosso de Cisterna, capturing more than 100 of the enemy. Meanwhile, Task Force Paulick pushed ahead against strong opposition and friendly mines, losing a company commander, two medium tanks, a light tank, and a tank destroyer before securing its objective.

Staff Sergeant Joseph M. Brown remembered the advance, and in particular Pfc. Henry Schauer, calling him “the best BAR-man I have ever seen.”

When the task force was halted by enemy resistance, Pfc. Schauer climbed out of a ditch and walked slowly toward the enemy. Four German snipers made Schauer their prime target. With one burst from his BAR he killed two snipers at 170 yards; he then took out the two others with individual bursts from his BAR. Running to catch up with his buddies, he spotted a fifth sniper whom he dispatched on the run. When two German machine guns opened up on the group, everyone hit the ground except Schauer.

Second Lieutenant James M. Dorsey, Jr., remembered, “The man acted as though nothing could kill him. He assumed the kneeling position on the bank of a ditch. Bullets from both machine guns swept about him, miraculously missing him by inches. Fragments from enemy shells, which burst no more than 15 yards from him, hit the ground all around him. He permitted none of this fire to ruffle his composure. Pfc. Schauer engaged the first machine gun, the one 60 yards away, opening up on it with a full clip of ammunition. In one long burst of fire he killed the gunner and the man alongside him. He put a new magazine in his BAR, fired two short bursts, and killed the two remaining Germans who ran to man the weapon.”

In similar fashion, Schauer knocked out the second gun. The following day he took on an enemy armored vehicle and machine gun, killing the entire crew while standing fully exposed to its fire. For his heroics Schauer, of Scobey, Montana, was awarded the Medal of Honor and promoted to technical sergeant.

While the main attack went in against Cisterna, the neighboring 45th Infantry Division launched an attack to protect the corps’ left flank. Here the success of the advance threatened the rear of the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division, which in turn protected the flank of the I Parachute Corps. This caused the German command to launch a tank-supported counterattack. General Truscott rushed up a battalion from the 1st Armored Division, and the situation was soon stabilized. On the right flank of the attack, the 1st Special Service Force had reached Highway 7 and the railroad. This greatly aided the 15th Infantry’s advance to the same objectives. But here, too, a tank-supported counterattack threatened to penetrate the thin lines of the Devil’s Brigade. Reinforcements were rushed forward and a slight withdrawal made before the threat was neutralized.

The Germans quickly realized they were in considerable difficulty. They had few reserves, and the ferocity of the attack made it clear that this was the long-awaited breakout from the Anzio beachhead. General Traugott Herr, commanding LXXVI Panzer Corps, requested permission to withdraw. General von Mackensen, commanding Fourteenth Army, refused to make the decision and referred the withdrawal request to Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, the highly capable German commander in Italy.

Kesselring refused the request. He feared that a withdrawal would expose a gap between his Tenth and Fourteenth Armies that the Allies would exploit. Instead he suggested to von Mackensen that he commit his reserves at Cisterna to halt the American advance. But General von Mackensen was unwilling to do that because he believed that the main attack would come not at Cisterna, but in the Aprilia-Albano sector of his front. This would put the Allies on the Alban Hills, a perfect blocking position to halt any retreat of the Tenth Army from the Cassino front. In fact, General Clark was considering doing just that, but for the moment the main Allied thrust was aimed in fact at Cisterna.

At the front the 362nd Infantry Division had committed all its reserves against the attacks of the 1st Armored and 3rd Infantry Divisions. So had the 715th Infantry Division. Each division had already lost nearly half its strength. By nightfall on the second day of the Allied offensive, Kesselring realized that the Fourteenth Army could not hold the beachhead. He began suggesting to Col. Gen. Heinrich Gottfried von Vietinghoff, commanding the Tenth Army on the Cassino Front, that he consider his withdrawal options. That same night, May 23, von Mackensen ordered his I Parachute Corps to withdraw to a secondary defensive line.

Although it took some time, the decision by the German commanders that the Anzio beachhead could no longer be contained soon made itself felt at the front. Although the Germans still stoutly defended what positions they needed to cover their withdrawal, they were, in fact, now retreating. By midday on May 24, CCB of the 1st Armored had crossed Highway 7, cutting one of two major routes of withdrawal for the Germans. Cisterna was nearly cut off. General Allen then went after the remaining route of German withdrawal. This road, the Cori Road, was attacked by Lt. Col. Frank F. Carr’s battalion of light tanks. Colonel Daniel’s CCA continued to push the remnants of the 362nd Infantry Division past the Mole Canal.

Colonel Carr’s battalion moved quickly to accomplish its task. Difficulty in crossing a railroad embankment, minefields, and long-range artillery fire delayed the advance. Traffic congestion contributed as well, as other tanks of CCB clogged the same access roads. It was two hours before Carr could assemble at Highway 7 and begin his assault, but once underway with the 91st Field Artillery Battalion in support, the advance moved swiftly. Overrunning enemy tanks and antitank guns unprepared for the American attack, the battalion began to encircle Cisterna. Supported from a distance by an armored infantry battalion and some medium tanks, the light tank battalion had all but trapped the German defenders.

But the job of taking Cisterna still rested with General O’Daniel’s 3rd Infantry Division. The heaviest fighting on May 24 and 25 was in the 7th Infantry Regiment’s sector. The 1st Battalion was brought forward from reserve and sent in to clear the ruins. Initially the advance was lightly opposed, but around 0930 Company C encountered heavy resistance near the railroad tracks. Additional enemy forces controlled the nearby high ground. The entire area was crisscrossed by machine guns, rifles, and 88mm guns. Antipersonnel and antitank mines covered all approaches to the enemy positions.

Company C attacked, infiltrating one platoon at a time across the railroad tracks. Once across, the Americans mopped up each enemy position in turn. The attack, however, disorganized the company, and it was replaced by Company A. Company A quickly cleared the high ground against modest opposition, which in turn allowed Company C to finish clearing out the railroad area defenses. By the afternoon of May 24, the 1st Battalion, 7th Infantry was following the 3rd Battalion into Cisterna itself. The Germans had, as usual, made good use of the shattered rubble that had once been the town of Cisterna, and the advance was strongly opposed. But the defenders were now cut off, low on ammunition, and without hope of relief. By late afternoon on May 25, Cisterna was being mopped up by the 3rd Battalion, 7th Infantry.

Lieutenant Colonel Everett W. Duvall’s 2nd Battalion, 7th Infantry approached Cisterna from another direction, targeting the railroad station. Although initial opposition was light, as it crossed the railroad tracks about 600 yards south of the town, the battalion was struck by machine-gun, mortar, and self-propelled artillery fire. Companies E and G attacked and in a fierce fight cleared the area of the enemy despite heavy casualties.

Company F entered Cisterna early on the morning of May 25 and cleared a third of the town. A large castle in the town center delayed the clearing for a while until two medium and two light tanks from the 751st Tank Battalion arrived. The sole entrance to the castle was covered by an enemy antitank gun blocking any attempt to enter. Company F put a machine gun atop a house to suppress the enemy’s fire while a medium tank raced through the castle entrance and knocked out the gun.

Some 250 prisoners were brought out of a cave under the castle and another 60 from caves in the area. After four of the bloodiest months in American military history, Cisterna had fallen.

Nathan N. Prefer is the author of several books and articles on World War II. His latest book is titled Leyte 1944, The Soldier’s Battle. He received his Ph.D. in Military History from the City University of New York and is a former Marine Corps Reservist. Dr. Prefer is now retired and resides in Fort Myers, Florida.

Looking for more information on the 3rd div 30th regiment co E during anzio,

“The Allied amphibious landing at Anzio, south of Rome, was intended to initiate a lightning strike against the City of Light…”

Paris, not Rome, is what has long been called the “City of Light,” or “Lights” — “La Ville-Lumière” — partly due to its early installation of gas lights but is actually due to its historical legacy. It used to be named such because Paris was the native place of the Age of Enlightenment and was known as a center of education and ideas throughout entire Europe.

Rome, on the other hand, has always been known as “The Eternal City.”

The author refers to Rome as the “City of Light;” however, Paris has always been called “La Ville Lumiere” for both its early installation of many many gas lights as well as having been the intellectual center of Europe for many years.

Rome has always been called “The Eternal City.”

Oddly enough, the link for this piece uses the above.

My uncle, Leo Feinstein from Brooklyn NY, was a combat engineer attached to the 2nd Ranger Battalion since the invasion of Sicily. He took part in the Rangers’ night attack at Cisterna, where they had the ill fortune to come out of the ditch into a Panzer regiment that Allied intelligence had missed. The fighting was so intense that he put some of the soil he lay on in an envelope, so that if he was killed his family would have some of the ground he died on. He was in a dwindling group that was led by Sergeant Robert Ehalt, who led his five remaining men back to their lines. Every other man in both Ranger battalions was either killed or captured, and many of those wounded. Eventually, about one third of the captured Rangers managed to escape back to American lines.

After that debacle he was sent to the 1st Special Service Force. The Anzio bridgehead took a pounding from a 15- inch naval rifle mounted on a rail car that was rolled back under camouflaged cover after only a few shots so it couldn’t be located and targeted. My uncle was one of a patrol sent out to find “Anzio Annie”. He had the bad fortune to step on a “Bouncing Betty” mine, a nasty device with a spring underneath. When the pressure of a foot was released, the mine, filled with ball bearings, would bounce up three feet and go off. Having been an engineer, he recognized that he had cocked the spring, kept his foot on it, and the mine went off under his foot.

He not only lived but kept his foot and his toes, at the cost of two years in hospitals treating complications.

Ironically, when he moved to Maryland in the ’60s he lived near Aberdeen Proving Grounds and found himself downrange from Anzio Annie again.

How do I get a list of Army Rangers who fought with Darby? My wife’s dad is one of them.

PFC Dutko was in Company A, not I. My grandfather, PFC George Schultz, D.S.C., was also a BAR man with Company A and was in the battle too…in fact his Distinguished Service Cross was awarded for actions the same day (May 23, 1944) after single-handedly attacking a German stronghold of 3 MG’s and wiping it out (and later wiping out another stronghold by himself). The actions were remarkably similar Dutko’s, though of course poor Dutko lost his life while my grandfather survived, albeit with a mortar round blowing off the center of his lower lip before the assaults and a flesh wound in the arm from a MG during it.

Horrible day by any measure.

ERRATA: This article says that SSgt. George J. Hall died just a few days after his MOH action. According to DoDs Medal of Honor website (https://www.defense.gov/News/Feature-Stories/story/Article/3035320/medal-of-honor-monday-army-staff-sgt-george-j-hall/), as well as other sources, “Unfortunately, Hall’s post-war life was cut short by complications related to his injuries at Anzio. He died on Feb. 16, 1946, nearly two years after that day in battle. He was 26. “