By Erich B. Anderson

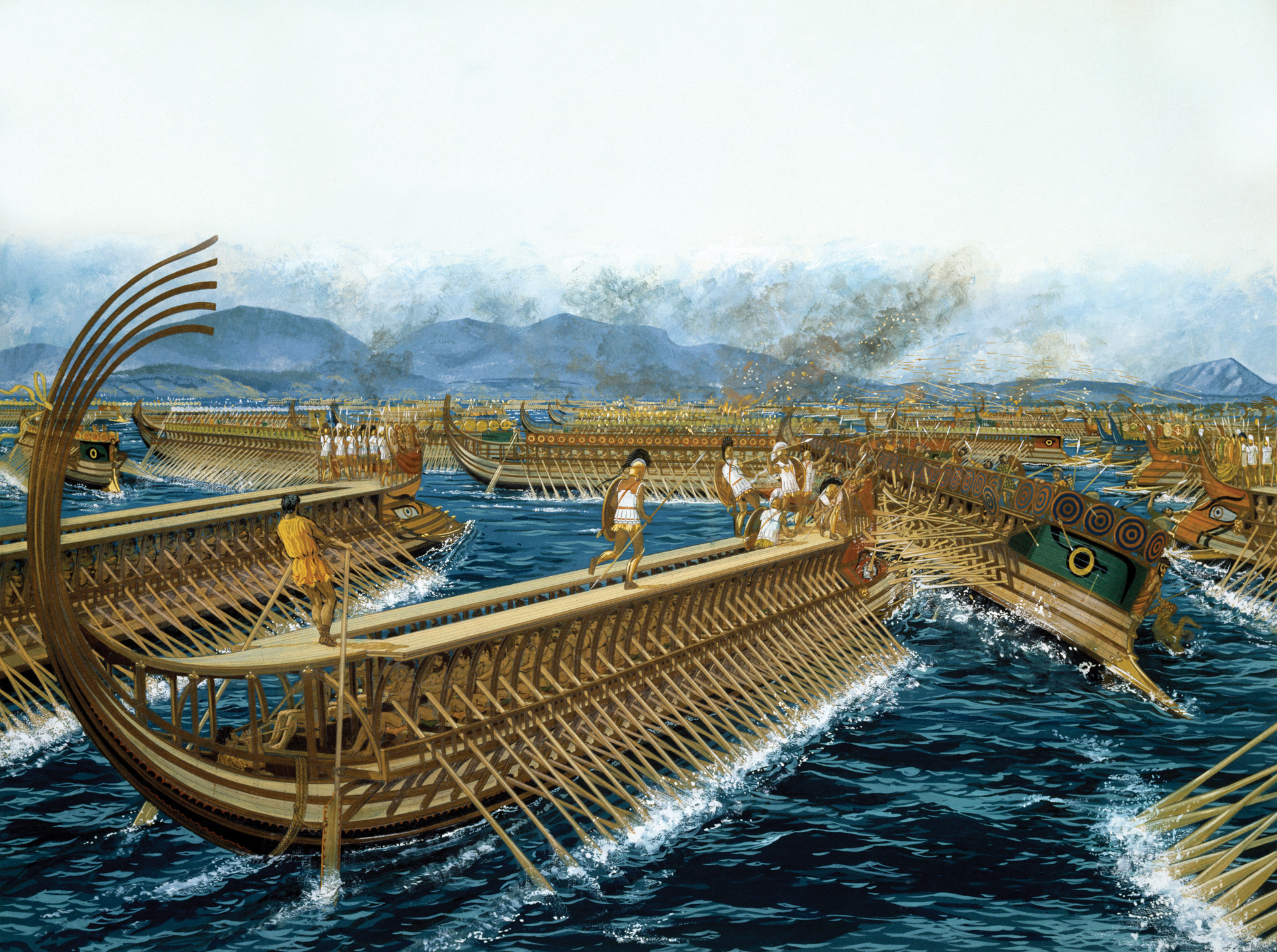

As the sun rose shortly after dawn on a morning in late September 480 BC, 170 rowers densely packed on three tiers within an Athenian warship strenuously pushed their oars to propel their vessel forward as fast as possible. The captain, Aminias of Pallene, had given the order for the crew to advance while nearly all of the other Greek ships in the fleet either stayed in place or moved slightly in reverse as they faced the huge armada of the formidable Persian Empire within the narrow Straits of Salamis. Aminias was one of, if not the first, Greek captain to decide to attack; thus, his command was carried out by the rowing master responsible for making sure the oarsmen rowed fast in unison, and the helmsman, who maneuvered the trireme to strike the closest vessel in the approaching Persian fleet.

Right before impact the pilot ordered the rowing master to have the crew quickly switch to backing water with their oars so the heavy, wooden ram covered with solid bronze at the prow of the ship did not penetrate too deep into the enemy vessel and get lodged. But the attempt was made in vain, for the ram of the Athenian trireme crashed into the Phoenician ship with such force that it became stuck, and the oarsmen could not reverse out of the penetrated vessel. With the two warships locked together, the Greek archers and hoplites on board began to combat the Persian marines of the Phoenician warship. A bloody fight ensued on the decks over control of the vessels. It was one of many ship-to-ship struggles that played out during the historic naval clash at Salamis.

Over a decade before Aminias and his crew initiated not only one of the greatest naval battles in antiquity, but also one of the most significant military encounters of Western civilization, the small city-state of Athens aroused the fury of the Persian kings who ruled over the most powerful empire the world had seen up to that time.

By supporting the formerly independent Ionian Greek cities during their revolt against the Persian Empire in 499 BC, the Athenians had earned the ire of King Darius. Swearing revenge against the Athenians, Darius in 490 BCled a great army into Greece. The Persians met the Athenian army in battle at Marathon that year. Although heavily outnumbered, the Athenians prevailed against the Persians.

Although Darius contemplated another invasion of mainland Greece, he died in 486 BCwithout achieving his vengeance. At the time of his death he was engaged in putting down a rebellion in Egypt. The unfinished business with Athens fell to Darius’s son Xerxes; however, Xerxes had other scores to settle first. After Xerxes crushed uprisings in Egypt and Babylonia, he was free to pursue his father’s goal of conquering mainland Greece.

As the Persians were occupied with the Egyptians and Babylonians, a new man named Themistocles was rising to power in Athens. The increasingly popular politician firmly believed that the best way to protect Athens from the threat of the Persian Empire was to greatly expand the fleet. The discovery of rich deposits of silver at Laurium enabled the Athenians to fill their coffers, and Themistocles successfully managed to convince his fellow citizens that the surplus wealth should be spent on overhauling and expanding the Athenian navy. The Athenians embarked on a ship-building program in 483 BCthat produced 200 new triremes.

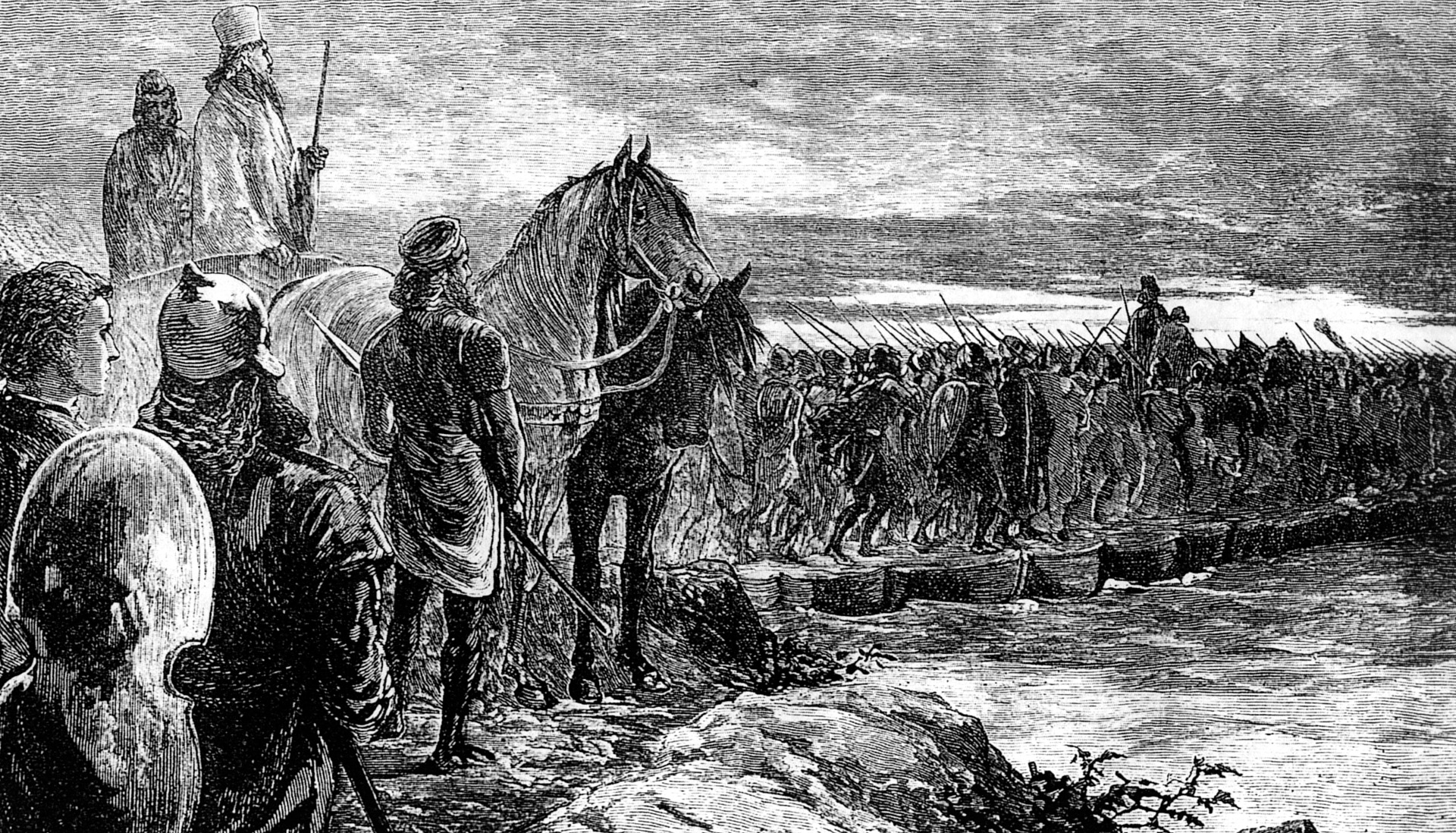

Xerxes raised an army of approximately 150,000 soldiers in the spring of 480 BC. His army crossed the Hellespont in May on two massive pontoon bridges built atop ship hulls lashed together with heavy cables and anchored at right angles to stabilize them in the swift current.

While the bridges were being built, a severe storm wrecked them. The event so angered Xerxes that he had the men supervising the construction put to death. For disrupting his plans, the Great King also had his men symbolically “punish” the water of the straits by whipping and branding it as if it were one of his unruly subjects. Afterward, the construction resumed and the bridges were completed.

Once on European soil, the Persian army coordinated its movements with the gigantic Persian fleet that numbered approximately 1,200 warships. The grand fleet was composed of squadrons of various subjugated peoples. The Phoenicians furnished 300 warships, the Egyptians furnished 200 warships, the Cyprians furnished 150, and the Ionians furnished 100. The Phoenician squadron was the strongest part of Xerxes’ navy. The marines on board the Persian warships were armed and armored like Greek hoplites, even though they might not have been Hellenistic in origin.

The average complement of soldiers on the Greek ships was 10 hoplites and four archers. In contrast, the Persian vessels included 14 of their own hoplites or archers as well as a contingent of 30 additional Medes, Sacae, or Persian warriors.

While Xerxes was the overall commander of both the land and naval forces, Persian military commanders served as admirals of the fleet. Chief among them was Ariabignes, a half-brother of the king and the son of Darius. The other leading admirals were Achaemenes, another son of Darius and full brother of Xerxes, Megabazus, and Prexaspes. Achaemenes led the Egyptian fleet, Ariabignes led the Ionians and Carians of southwest Anatolia, and Megabazus and Prexaspes led the rest of the fleet.

The Persian admirals were relatively inexperienced in naval warfare, thus their main purpose was to keep foreign subject commanders and captains in line. The real force behind the Persian fleet was a trio of Phoenician kings who were experts in naval tactics. These royal figures were Tetramnestus, king of Sidon; Matten, king of Tyre; and Merbalus, king of Aradus.

Before Xerxes had initiated the campaign with his troops, many Greek city-states met at the Isthmus of Corinth and decided to band together in the fall of 481 BC. They formed a confederation called the Hellenic League. Under the terms of the agreement, all hostilities between members were to cease immediately. This brought closure to the two decades of strife between Athens and Aegina.

The Spartans commanded both the land and sea forces of the Hellenic League. This was the case even though the Athenians and their supporters believed that the chief admiral of the fleet ought to be an Athenian since the city-state had contributed more ships than any other Greek member. However, the Spartans had the support of their Peloponnesian allies, so the Athenians were outnumbered in the league and were forced to concede the leadership not only on land, but also at sea. Like the role the Phoenicians and their rulers had in the Persian fleet, Themistocles and the Athenians were the true naval strategists of the allied Greek navy.

United against their common foe, the Greeks began to make preparations for their resistance. They proceeded with their plans despite the Oracle of Delphi’s prophecy that not only would disaster befall the Greeks, but also that the Athenians should flee. The prophecies further stressed that the only chance the Athenians had for survival was to put their faith in a wooden wall. Many Athenians interpreted this to mean that the construction of a wooden wall and palisade on the Acropolis would save them from the Persian onslaught. Themistocles made a less literal interpretation. He managed to convince a majority of the Athenians that the oracle was actually referencing the wooden bulkheads of the Athenian warships. As a result, the Athenians embraced Themistocles’ belief that the only way to stop the invasion of the Persian Empire was to defeat its naval forces at sea.

Many members of the Hellenic League believed that the best place to organize resistance to the Persians was at the Isthmus of Corinth, the narrow stretch of land that connected the Peloponnesian Peninsula with the rest of Greece. The Athenians argued that such a strategy would leave them vulnerable to the ravages of the Persian army. Furthermore, the Athenians observed that troops stationed at the isthmus could be easily outflanked by the Persian fleet. The Peloponnesian members of the league eventually came to appreciate the Athenians’ need for protection; as a result, the Greeks assembled an army to confront the Persians in Thessaly.

While the great Persian army was crossing the Hellespont, the Greeks sent an army of 10,000 hoplites to the Vale of Tempe in northern Thessaly. This army consisted of two contingents: one was led by the Spartan Evaenetus and the other was under the command of Themistocles. The journey north was made in vain, however, because the Greek commanders discovered there were too many passes for a force of their size to sufficiently hold against the enemy, so they withdrew to the Corinthian isthmus.

The two sides continued to debate the best way to defend their respective homelands. The Greeks ultimately decided to make a stand in central Greece at the narrow pass of Thermopylae. Where the army would be able to defend the pass while the fleet took up a position at Artemisium near the northern end of the island of Euboea. When the Greek navy took up its position in late August, it had 271 triremes. The commander of the Greek fleet was a Spartan named Eurybiades.

For the Persian fleet, Xerxes instructed his troops to build a canal through the Athos Peninsula. By traversing the landmass, as opposed to going around the southern tip, the vessels could avoid the storms that had devastated the fleet on the campaign led by Mardonius in 492 BC. The Persian land and sea forces rendezvoused in Therma before splitting up again so that the army could penetrate deeper into mainland Greece.

The Persian army reached the Greeks first at Thermopylae near the end of August. Waiting for them were 8,000 hoplites and light infantry led by the Spartan King Leonidas with his royal bodyguard of 300 elite soldiers. Meanwhile, the Persian fleet experienced great hardship on its way from Therma to Artemisium. Storms destroyed 400 warships. Persian woes continued after they reached the Greek fleet, for the Phoenicians sent a squadron of 200 vessels south around Euboea in an attempt to trap the Greeks between the two contingents of the Persian navy. Storms decimated the Phoenician squadron. Regardless of its heavy losses, the Persian fleet had approximately 700 warships by the time it reached the port of Aphetae. Their new position put them in close proximity to the Greek fleet at Artemisium.

The sight of such a huge fleet greatly intimidated the Greeks and caused many to lose heart. But bribery, as well as Themistocles’ strong leadership, enabled the Greeks to hold their army together. Shortly afterward, the Greeks received the good news that 15 Persian ships had accidently separated from the main fleet and sailed into the clutches of the Greek navy at Artemisium. The Greeks quickly captured the galleys. Intelligence gleaned from the captured Persians, as well as from a Greek informant in the Persian navy, alerted the Greeks to the southern movements of the Phoenician squadron. Word was then sent to the 53 Athenian warships in reserve to protect Athens and the rest of Attica from possible attack. If necessary, the reserve force was to intercept the Phoenician squadron so that it could not assault the main Greek fleet from the rear.

While the Persians were preoccupied with making repairs to some of the vessels damaged by the storm, the Greeks went on the offensive. When the two sides met, the Greeks proved that they were not foolishly overconfident, for even though the more numerous Persian ships surrounded their forces, the Greek triremes pulled off a brilliant defensive maneuver. The Greeks formed themselves into a circle to prevent the Persian fleet from using its superior numbers to overwhelm them. Eventually, the Greek captains became too confined within their circle, so they broke through the Persian lines. The Greek ships managed to escape (probably because they were lighter as a result of carrying fewer troops), seizing 30 Persian vessels during the fighting.

After reports of the misfortune that befell the Phoenician squadron reached the Greeks, the 53 ships of the Athenian reserve joined the rest of the allied fleet. The reinforced Greek fleet advanced again to confront the Persian naval forces. On the second day of combat at Artemisium, the Greeks achieved another minor victory when they sank several Cilician galleys. On the third day the fighting grew in intensity. When the larger Persian fleet once again encircled the smaller Greek navy, fierce fighting raged throughout the day. When it was over, both sides had incurred heavy losses.

Meanwhile, a traitor informed Xerxes of a path at Thermopylae that would allow his forces to surround the Greeks stationed there. When the Greek army learned that the Persians had discovered a way to attack them from the rear, a large number departed on the belief that the position was untenable.

Spartan King Leonidas resolved to make a stand defending the narrow space between a steep hillside and the sea. His small force consisted of 1,400 hoplites. Leonidas’s troops repulsed repeated Persian assaults for two days, inflicting heavy losses on the enemy while suffering relatively light losses themselves. On the third day, the Persians outflanked and annihilated Leonidas’s force. Leonidas and his elite royal bodyguard made a last stand in the defile in which they were all slain.

Following the Battles of Artemisium and Thermopylae, the Greek fleet withdrew to the island of Salamis near the coast of Athens. Putting their faith in the success of their large fleet, many Athenians had already evacuated from the territory of Attica to Salamis, the island of Aegina, or the city of Troezen, which was located in the eastern Peloponnese. With no allied forces north of the Isthmus of Corinth to halt the advancing Persian army the remainder of the inhabitants of Athens were evacuated. The few citizens who remained in Athens fortified themselves on the Acropolis, putting their faith in the words of the oracle of Delphi. Yet the fortifications were of scant use against such overwhelming numbers. By early September, the surrounding countryside of Attica was ravaged and the city of Athens was destroyed by the Persian troops.

After the Greek fleet helped evacuate the Athenian populace, the allied admirals once again debated whether they should withdraw to the isthmus. The location had become even more appealing to the Peloponnesians whose land forces remaining on the peninsula had begun to build a wall across the narrow stretch of land after the defeat at Thermopylae. The next day the Persian fleet arrived at the Bay of Phaleron to the east of Salamis. The Persian navy had been reinforced, therefore maintaining its strength of 700 vessels. In contrast, the Greeks had approximately 300 triremes.

Just when it seemed as if Eurybiades had made his decision to flee to the isthmus, Themistocles was said to have sent one of his most trusted servants, Sicinnus, to the Persians during the night to warn them about the flight of the Greek fleet. The sly Athenian admiral had his messenger tell the Persians that he had switched sides; however, he hoped his message would lure the enemy to the narrow confines of the Straits of Salamis where their advantage of superior numbers would be negated. At the same time, the advance of the Persians would also force the Greeks to engage in combat. It was a fight that Themistocles was confident his side could win.

The ploy worked exactly as Themistocles had planned, for Xerxes and his naval commanders immediately took steps to confront the Greek fleet. Even though it was nighttime, the crews and marines of the Persian fleet boarded their ships and moved to block all possible escape routes that the fleeing Greeks might use. The majority of the imperial ships shifted east toward Phaleron Bay, although the 200-strong Egyptian squadron sailed for the western side of the island of Salamis to block that path as well. Additionally, a contingent of 400 elite troops was sent to the island of Psyttaleia to assault any Greek individuals or ships that reached the coasts during the fighting.

Themistocles, with the help of his long-time Athenian rival Aristides, alerted Eurybiades and the other allied commanders of the Greek fleet to the actions of the Persians; this was backed up by a report from a Greek ship that had defected from the imperial forces. Since withdrawal to the isthmus was no longer an option, the Greeks agreed to board their ships and confront the Persians at dawn.

At sunrise the Greek fleet was in position with Eurybiades and the 16 Spartan ships in the traditional place of honor on the right wing, the large Athenian navy of 200 triremes on the left, and the 30 Aeginetan vessels and 14 other warships of the Greek allies in the center. The Greek reserve consisted of 40 Corinthian ships.

Xerxes watched the movement of his fleet from the mainland. He was amazed that the greatly outnumbered Greek navy had the audacity to give battle. The Persian fleet was not at all intimidated by the united front presented by the allied Greek fleet. Drums, pipes, and war chants created a terrific din as the opposing sides approached each other. Before the opposing fleets made contact, the Greeks paused briefly to maintain their formation before proceeding.

After the Athenian trireme captained by Aminias slammed into the Phoenician vessel and became stuck in it, the marines of both ships engaged in brutal combat. At first the two sides exchanged missile fire consisting of arrows and javelins before the more heavily armed Greek hoplites and Persian marines confronted each other. The Athenian crew was outnumbered, but it did not take long for their allies on other ships to rush in and help. With their aid, Aminias’s crew not only managed to dislodge their ship, but they also tore off the entire sternpost of the Phoenician vessel. Once free Aminias and his crew left the disabled ship so that they could attack their next target in the Persian fleet.

About the same time that Aminias’s vessel made contact with the enemy, an Aeginetan trireme successfully rammed into a Phoenician ship. A Greek trireme led by Democritus from the island of Naxos was the next vessel to attack. Lycomedes’ ship was the first to successfully capture a Persian vessel.

During the initial clash, a Corinthian contingent sailed to the northwest apparently to meet the threat posed by the Egyptian fleet in the western passage. But it might also have been trying to deceive the Persians into believing that the Greeks would not make a united stand. Numerous collisions occurred in the front ranks, and boarding parties became entangled. The fighting was general from the Cynosura Peninsula to the larger of the two Pharmakoussae Islands.

Near that island, on the western side of the battle, the Phoenicians on the Persian right wing attempted to seize the offensive from the Athenians by breaking through their front line. But the first two lines of the Athenian fleet were so densely packed together, and their flank was protected by the Pharmakoussae island, so the Phoenicians failed in their attempts. The confined space in which the combatants struggled also contributed to the Phoenicians’ failure. Moreover, the large crews on board their ships completely negated the superior speed and agility of their vessels. Despite the best attempts of their crews, the Phoenicians were unable to carry out crucial maneuvers.

Desperate to break through the Athenian line, yet exhausted from the overnight to early morning exertions, the Phoenician navy began to lose its cohesion. The Greek fleet stayed in line while also managing to exploit the deteriorating formation of the enemy. As the fighting progressed over the next few hours, the situation worsened for the Phoenicians, especially at 9 amwhen a strong, albeit routine, sea breeze began to blow throughout the straits, causing the surface of the water to become rough and choppy. While the lower and broader Greek ships were better able to deal with the sudden swell, the Phoenician triremes, with their high decks, bulwarks, and sterncastles, were affected much more by the wind and waves. Under these conditions many of the Phoenician crewmen could not properly control their ships and their sides and sterns became vulnerable to attack. The Greeks exploited these weaknesses with deadly efficiency.

While the Phoenicians initially were able to withstand the Greek assaults, eventually they succumbed to them. Because the Phoenicians were skilled mariners, their morale remained high. They refused to capitulate without a struggle. They were acutely aware that Xerxes was watching them from his perch on the coast of the mainland. What is more, the Phoenicians, as well as the rest of the Persian fleet, still outnumbered the Greeks. The presence of the massive Persian flagship of admiral Ariabignes towered over the lesser vessels like a floating fortress. It inspired the courage of crews in the Persian ships near it.

Aminias and his lieutenant, Socles, realized that the Greeks needed to destroy the Persian flagship. The marines on the Persian flagship showered on the Greek vessels nearest to them “arrows and javelins as from a city wall,” wrote Plutarch. “[Ariabignes] was a brave man, the strongest and most just of the king’s brothers. Aminias of Deceleia and Socles of Paiania, sailing together, rammed him head-on. The two ships were locked together by their bronze beaks. [Ariabignes] tried to board their trireme but the two Athenians hurled him into the sea with their spear thrusts.”

The death of Ariabignes and the loss of their flagship came as a heavy blow to the Persians. At that point, the Persian fleet’s command structure collapsed for there was no designated succeed successor to Ariabignes. The surviving captains gave conflicting orders that resulted in great confusion.

Inevitably, the chaos was too much for the Phoenicians, and their ships attempted to flee to safety. The Corinthians returned from the north and fell upon the Phoenician right wing, striking it in the flank. When the Phoenicians began to flee, the Corinthians pursued them and attacked them in the stern.

The Persian fleet was deployed five lines deep in some places. The Phoenician retreat precipitated a disaster as the retreating vessels crashed into the line behind them. The vessels in the rear continued to advance in an effort to impress their Great King with acts of bravery and self-sacrifice.

The dramatist Aeschylus described the effect the heavy winds and the unrelenting attacks of the Greeks had on the Persians, specifically the Phoenicians. “At first the Persian line withstood this shock; but soon our crowding vessels choked the channel, and none could help each other,” he wrote. “Soon their armored prows smashed inward on their allies, and broke off short the banks of oars while the Greek ships skillfully encircled and attacked them from all sides.”

Many ships were lost and more men perished in the sea, especially among the Persian and Mede marines that were on board. While the Greeks and Phoenicians were sea peoples and could swim, the Persians and their Asiatic allies had no real experience at sea. Many of these sailors and marines were unable to reach the shore and drowned.

A small group of Phoenicians, including captains and aristocratic warriors, managed to escape their damaged or captured ships and reached the coast. When they were brought before Xerxes, the Phoenicians desperately pleaded for the Great King to hear their case. Their failure in battle was not their fault, the Phoenicians claimed, but a result of the treachery of the Ionian Greeks in the Persian fleet.

As the Phoenicians made their accusations, Xerxes witnessed one of his ships, a Greek trireme from Samothrace, striking an Athenian galley from the stern quarter with its bronze prow. The Samothracian trireme successfully disengaged thereby avoiding entanglement. As the Samothracian vessel reversed away from the disabled Athenian ship, an Aeginetan trireme of the Greek navy rammed the Samothracian. The Samothracians hurled their javelins with deadly accuracy, thus killing the majority of the marines on the Aeginetan ship. After decimating the defenders, the Samothracians seized the enemy vessel.

Xerxes, who watched the Samothracian crew distinguish itself before his eyes, ordered the immediate decapitation of the Phoenician accusers. To justify this extreme act, the Great King stated that bad men should not slander those who are better than them.

By that point, the Phoenician line was entirely broken. Shortly afterward, the Cypriot line collapsed as well. Following the example of the Samothracian ship, the other Persian allies in the center and on the left side of the Persian fleet fared much better than the Phoenicians throughout the early phases of the battle.

The collapse of the Persian right wing meant that the Athenians and Aeginetans were free to attack the remaining resistance in the flank as the Spartans and the rest of the allied Greeks assaulted the enemy front line. The assault on the Persian flank eventually intensified to such an extent that the Cilicians and the rest of the Persian center broke. After witnessing the flight of the Phoenicians and the death of their admiral, Syennesis, the Cilicians could take no more. It was then that the Persian left wing also began to buckle.

As midday approached, Aminias began hunting for his next target. He came across the ship of Queen Artemisia of Halicarnassus. The idea that a woman was one of the enemy commanders so infuriated the Athenians that they put a price of 10,000 drachmas on her head. Unfortunately for Aminias, he and his men were unaware of the great worth of the vessel they pursued because they did not know that the Greek ship belonged to Artemisia. As the Athenian crew prepared to ram the retreating galley, Artemisia ingeniously ordered her men to aim their ship at one of the nearby Carian vessels. When Artemisia’s trireme slammed into the unsuspecting vessel, the ship sank and all of the Carians on board perished, including King Damasithymus of Calynda, a Carian city southeast of Halicarnassus.

The ploy worked perfectly, for Aminias suspected that the Greek ship had deserted the Persian cause and switched sides; thus, the Athenian captain and his crew searched for a different enemy galley to assault. Artemisia’s deception not only tricked Aminias, but also Xerxes. The Great King was aware of the encounter but did not know that his allied queen had attacked a fellow vessel in his own fleet. Rather than being punished for her treacherous act, Artemisia was praised for her martial performance.

The other Ionians and Carians valiantly held off the relentless assaults from their fellow Greek enemies, but they too were soon compelled to retreat. Aeschylus described the dire situation in which the Persian fleet found itself. “Crushed hulls lay upturned on the sea so thick you could not see the water, choked with wrecks and slaughtered men; while all the shores and reefs were strewn with corpses,” he wrote. “Soon in wild disorder all that was left of our fleet turned tail and fled. But the Greeks pursued us, and with oars or broken fragments of wreckage split the survivors’ heads as if they were tunneys or a haul of fish and shrieks and wailing rang across the water.”

In the final phase of the battle, the Athenians and Aeginetans exuberantly took on the remnants of the Persian fleet in increasing jubilation for their continuing triumph against such overwhelming odds. In this atmosphere of growing confidence, some of the Greeks playfully competed with their allies, who shortly before had been longtime rivals. As Themistocles’ flagship raced alongside the trireme commanded by Polycritus of Aegina, it was the Aeginetan vessel that managed to strike the enemy first. Once his target was removed, Polycritus yelled to the Athenian admiral and mocked him for saying Aegina was pro-Persian.

The former enemies continued to work in a synchronized fashion as they continued to carry out their devastating assaults on the retreating Persian ships. The Greeks did the most damage to the Persian fleet as it attempted to exit the straits and get back to Phaleron Bay. “The Aeginetans were lying in wait for them in the channel and did famous deeds,” wrote Herodotus. “For the Athenians dealing with those ships that put up some resistance or were trying to escape in the confusion and the Aeginetans dealt with those that were trying to get out of the straits. So any that escaped ran straight into the Aeginetans.”

The deadly flank attacks employed by the Aeginetans, along with the Corinithian reinforcements, effectively ended the naval Battle of Salamis. Any surviving ships in the Persian fleet fled to the safety of the bay in Attica.

Late in the day, with the straits no longer crammed with Persian ships, the path was open for the Greeks to attack the small Persian garrison stationed on the island of Psyttaleia. Aristides led a contingent of hoplites and support troops that landed on the coast when the Persian force was isolated with no hope of rescue by the battered Persian fleet. At the outset of the assault, Greek archers and slingers rained missiles down on the Persians. Greek hoplites and marines then rushed in to finish the job with their blades. They slaughtered the Persians to the last man.

Once the battle was over, the Greek ships towed as many disabled vessels as they could back to the coasts of Salamis. While the Greeks lost approximately 40 triremes, the Persians fared much worse, having lost more than 200 warships either destroyed or captured. Yet the imperial fleet still had hundreds of ships, so the Greeks were wary of of another major encounter. Such an attack never came. After Xerxes heard the advice of senior commanders Mardonius and Artemisia, the Great King decided to return to Asia. By destroying Athens, defeating the Spartans at Thermopylae, and establishing his rule over northern and central Greece, Xerxes had made a significant number of achievements, despite the outcome at Salamis. The loss at Salamis was certainly a major setback, but it was not the primary reason for his retreat. The approach of winter compelled the Persians to withdraw. The winter months made military operations extremely difficult on land and impossible at sea.

After the order for retreat was given, the fleet was the first to depart under the cover of night. A few days later, Xerxes and the army withdrew back to Thessaly. Once in friendly territory, yet still in Greece, the Persian army split up. Some of the troops accompanied the Great King as he traveled back to Persia. Others remained behind to serve under senior Persian military commander Mardonius. When the Greek fleet became aware of the flight of the Persian fleet, it quickly set off in pursuit. But the Greeks got only as far as Naxos before halting their pursuit.

The final showdown between the Persian Empire and the Greek city-states occurred the following year when Mardonius led his Persian army south to finish the conquest of Greece. The confederation of allied Greek city-states led by Sparta and Athens confronted the Persian troops at Plataea and vanquished them. Mardonius was slain in the battle. The Greeks then drove the Persians from their homeland.

Athens and her allies had successfully repelled an invasion by the mighty Persian Empire. In so doing, they remained free of oppression by a foreign power. From that point forward, Athens was free to achieve its full potential as manifested in the Golden Age of Athens.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments