By Flint Whitlock

It was, as the phrase goes, another perfect day in paradise. As the sun rose above the Pacific in the clear, cloudless sky east of the Hawaiian Islands, on December 7, 1941, the giant U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, on the island of Oahu, was just beginning to stir.

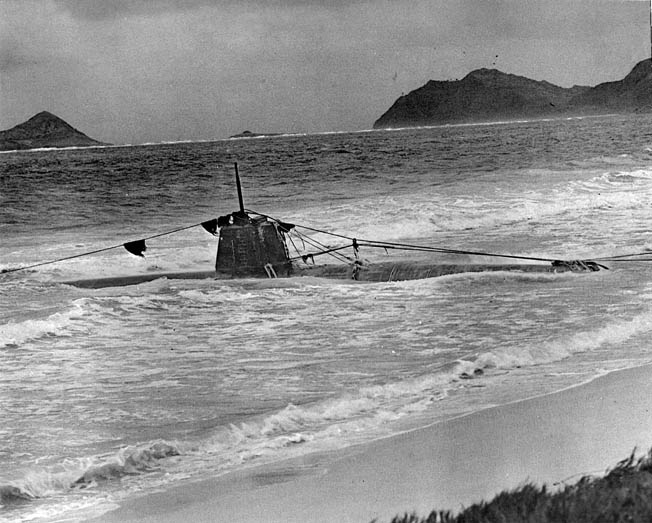

At 6:30 am, USS Antares (AKS-3), a U.S. Navy stores and supply ship of more than 11,000 tons, was approaching the mouth of the inlet leading into Pearl Harbor towing a steel barge. On the bridge of Antares was her skipper, Commander Lawrence C. Grannis. He suddenly noticed an unexpected object about 1,500 yards off the starboard quarter, something that looked suspiciously like the conning tower of a submarine.

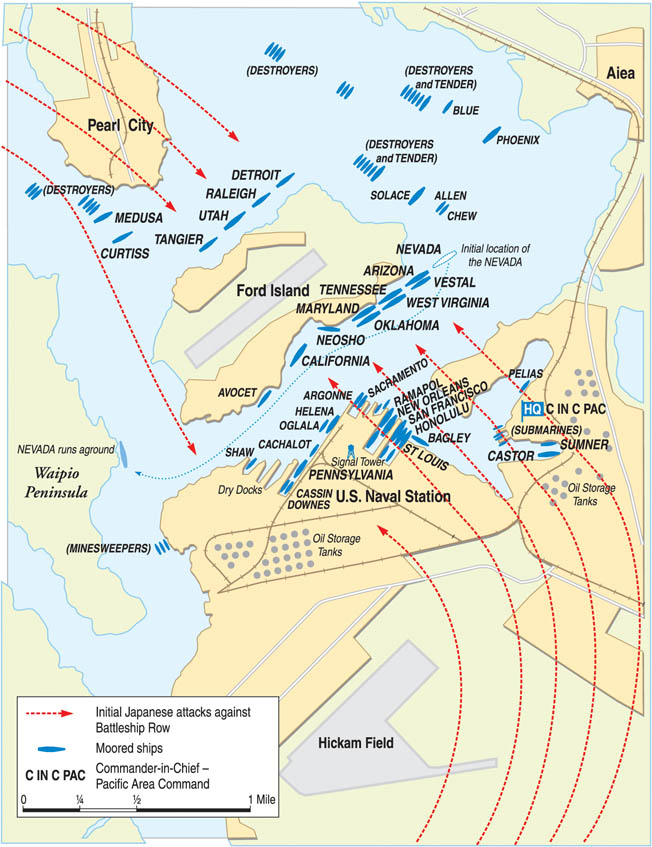

Grannis was indeed correct. The conning tower belonged to a 46-ton, 78-foot-long Type A Japanese midget submarine that carried two torpedoes and a two-man crew. It was one of five brought from Japan by five I-class mother submarines and launched five or six hours before the planned 8:00 am aerial attack was set to begin. Its mission was to enter the harbor, lie in wait, and torpedo whatever ships it could find once the general attack was underway.

As Antares was unarmed, Grannis radioed the nearby destroyer Ward of his finding; officers aboard Ward confirmed the sighting and at 6:40 went to general quarters. There was no reason why a submarine should be lurking in that area, especially one that appeared to be trying to sneak into the harbor behind Antares during the brief minutes when the narrow channel’s antisubmarine nets would be open.

Closing quickly on the submarine, which was now about five miles from the harbor’s entrance, Ward’s skipper, Captain William Outerbridge, brought the destroyer to within 50 yards of the unidentified craft and gave the order to fire. The first salvo of four-inch shells missed, but then a round struck the conning tower at the waterline and the boat keeled over. As the sub passed beneath Ward’s hull, depth charges were dropped on it. It popped to the surface momentarily, then went under for good.

Outerbridge sent a message detailing his actions to the 14th Naval District watch officer, Lt. Cmdr. Harold Kaminski, who passed it along to higher headquarters. The report caused a stir, and soon it seemed that everyone was trying to get in touch with someone at a higher level who could decide what the sighting and sinking meant and what to do next.

A call went to Admiral Husband E. Kimmel’s quarters on shore, where the admiral was preparing for a round of golf with Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short, commander of the U.S. Army’s Hawaiian Department; Kimmel was commander in chief of the U.S. Fleet in the Pacific. He threw on some clothes and was chauffeured to CinCPac headquarters, wondering if this was just another false alarm; there had been several “sightings” of Japanese ships, planes, and subs in the previous months, but they had all turned out to be nothing.

This time, as events would soon prove, this sighting and sinking was anything but nothing. It was, in fact, the precursor of a world-changing event, but no one at the time could appreciate just how momentous it was about to become.

50 Warplanes on the Radar

As Gordon W. Prange, Katherine V. Dillon, and Donald M. Goldstein wrote in At Dawn We Slept, arguably the most detailed and comprehensive account of the attack, “The Navy’s most serious error in this pre-attack submarine chapter of the Pearl Harbor story was its failure to advise the Army that a destroyer had sunk an obviously hostile submarine in the Defensive Sea Area. The incident might have provided just the added weight needed to move the Hawaiian Department from the No. 1 alert to No. 2 or 3, because a submarine snooping near Pearl Harbor could scarcely have been charged up to local saboteurs.”

To most of the military personnel in the Hawaiian Islands, the early-morning sinking of the midget submarine, however, passed unnoticed. Aboard the two dozen ships anchored in the shallow waters, hundreds of sailors were still in their racks, sleeping off a little too much drinking and carousing in Oahu’s bars and houses of ill repute on Hotel Street the night before. (The five aircraft carriers that normally called Pearl Harbor their home station were either on maneuvers far out to sea or in port in California, or had been transferred to the Atlantic).

Elsewhere, chaplains were preparing for their weekly church services, and cooks in shipboard messes and in mess halls on land were frying eggs and bacon and brewing gallons of coffee. Belowdecks on Arizona, the band was donning crisp white uniforms and getting ready to assemble on deck to play its daily rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the national colors were raised on the fantail.

At Schofield Barracks, U.S. Army soldiers of both the 24th and 25th Infantry Divisions, like their Navy counterparts, were either asleep or rolling slowly out of bed to begin their day. The same was true at the Army Air Bases at Hickam, Wheeler, and Bellows; the Marine airstrip at Ewa; the Naval Air Stations at Keneohe and Ford Island; and the tiny Haleiwa fighter strip. There the P-40 Warhawks and P-36 Hawks and B-17 Flying Fortresses were lined up in perfect rows so that they could be more easily guarded against sabotage—orders from General Short.

At 7:00 am, atop a mountain known as Kahuku Point 230 feet above the sea on the north shore of Oahu, two enlisted men—Privates Joseph Lockard and George Elliott––were about to shut down their radar set at Opana Mobile Radar Station. Bleary eyed, the two men had been up all night practicing with the radar equipment—something brand-new for the Army.

Just before he threw the power switch to “off,” Lockard noticed something unusual—an image on the oscilloscope indicating a large number of planes––more than 50—approaching the island. Neither he nor Elliott had any idea what it was. Elliott called the Information Center at Fort Shafter, where the pursuit officer and assistant to the controller, 2nd Lt. Kermit Tyler, was about to go off duty and get some shut-eye.

“Sir,” said Elliott, “there seems to be a large formation of planes headed our way.” He neglected to report that he estimated the number to be at least 50 planes.

Tyler thought for a moment, then remembered being told earlier that a dozen B-17s coming from California would be arriving in Oahu that morning. Those must be the bombers, Tyler assumed. “Well, don’t worry about it,” he told Elliott, then left the center without passing this information along to anyone else.

Deciding that the officer knew more than they did, Lockard and Elliott killed the power to the radar set and got ready to depart. The time was 7:20.

Meanwhile, a hundred miles north of Oahu, the vanguard of Operation Z—the long aerial train of warplanes that had been launched from a flotilla of carriers—was closing in on its unsuspecting target.

Rising Tensions Between the United States and Japan

In his request before Congress for a declaration of war against Japan delivered on December 8, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt stated that the attack, while “sudden and deliberate,” was also “unprovoked and dastardly.” From the Japanese point of view, however, it was far from “unprovoked.” Trouble between Japan and the United States had been brewing for many years, with the wheels of conflict set in motion shortly after the Great War ended in 1918.

Japan had been on the side of Great Britain and the United States, and had taken Pacific bases away from the Germans. As a result, Japan expected that she would be rewarded in some way, but was shocked and insulted when the Washington Arms Control Treaty of 1921-1922 determined the reduced size of the naval fleet that Japan would be allowed to have. Although Japan’s democratic government grudgingly accepted the treaty, the ultranationalists and the hard-line militarists who held great power in the government were outraged, feeling the treaty was a slap in the face.

If the Western powers would not grant Japan equal status, they vowed, then they would chart their own course with their own national interests in mind. With few natural resources of its own, Japan was dependent on foreign trade, but the hard-liners began plotting ways to invade its Asian rivals and grab the oil, coal, iron ore, nickel, copper, rubber, aluminum, magnesium, and other resources needed to expand and create an unrivaled military force.

Another slap came in 1930 when the London Naval Conference set further limits on the Imperial Japanese Navy and further aggravated the militarists. In September 1931, the Japanese manufactured an incident that gave them a pretext for invading Manchuria. After being accused of cruelties against Manchurian civilians and rebuked in 1933 by the League of Nations, Japan walked out of that body.

In 1937 Japanese troops at the Marco Polo Bridge in Shanghai exchanged fire with Chinese troops, and Japan, whose puppet government was by now operating under almost the full control of the militarists, launched a full-scale invasion of China, whose Nationalist leader, Chiang Kai-Shek, the U.S. supported. Three years later, Japan invaded French Indochina to seize the oil resources there, then signed the Tripartite Pact with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, thus creating the so-called “Axis.” This set the stage for a confrontation with the United States, which had decided to impose economic sanctions against Japan for her aggressive behavior.

The Blueprint For Pearl Harbor

In November 1940, with hostilities in Europe having broken out, Japan’s attention was captured by the surprise British raid on the Italian fleet anchored at Taranto. Although obsolescent, the British biplanes, operating from carriers, delivered a blow that sank or badly damaged three of the Royal Italian Navy’s modern battleships against a loss of just two planes.

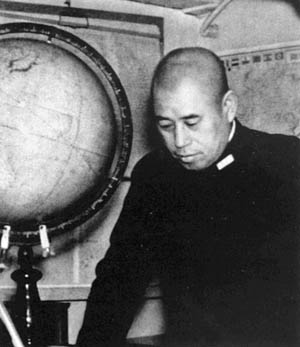

The attack inspired Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander in chief of Japan’s Combined Fleet, to begin thinking of how a similar attack––if war with the United States could not be avoided––could neutralize American military might in the Pacific. He began formulating a broad concept that would be a decisive, devastating katana thrust into the heart of America’s interests in the region––an attack against the U.S. Pacific Fleet in Hawaii and elsewhere.

To help refine the concept into a detailed, workable plan, Yamamoto called upon the advice and expertise of such officers as his chief of staff, Admiral Shigeru Fukudome; chief of the Japanese Naval Staff, Rear Admiral Osami Nagano; chief of staff of the XI Air Force, Rear Admiral Takijuro Onishi; and Commander Minoru Genda, a young, brilliant tactician and expert in naval aviation. For months the men discussed, argued, conceived, and discarded various ideas on how best to carry out such an attack—especially one that would require the undetected movement of a large fleet over vast distances.

Ironically, probably no one in Japan was more doubtful about a successful outcome than Yamamoto. In the 1920s, he had been a student at Harvard; later, he served as naval attaché in Washington. He knew firsthand the vastness of America’s industrial might and capacity; when it came to the ability to wage and sustain a long war over immense distances, America was the elephant, Japan the flea. His nation’s only hope was to strike such a crushing blow that America, left helpless and exposed, would be unable to prevent Japan from taking all the territory it wanted—or so the Japanese militarists believed—and would sue for peace.

Yamamoto was unconvinced that Japan could prevail in a protracted war. In a January 1941 letter to one of Japan’s arch-nationalists, he wrote, “Should hostilities break out between Japan and the United States, it would not be enough that we take Guam and the Philippines, nor even Hawaii and San Francisco. To make victory certain, we would have to march into Washington and dictate the terms of peace in the White House.”

Thus began a long, secretive process to launch a war that many (but not all) in Japan saw as “inevitable.” The planning went forward, and eventually a blueprint was drawn up.

The Collapse of Diplomatic Negotiations

To string the Americans along and make them think that peace was possible even while plans for war marched ahead, Japan sent a new ambassador, Kichisaburo Nomura, to the United States in February 1941 to engage in protracted negotiations with Secretary of State Cordell Hull that were little more than a smokescreen hiding his nation’s true intentions. Nomura himself was kept in the dark as to what those intentions were and dutifully carried out his assignment, believing that his efforts just might forestall all-out conflict.

In the summer of 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt persuaded Congress to freeze Japanese assets in the United States and shut off exports of oil and scrap iron, further infuriating Japan’s hard-liners. The militarists, led by General Hideki Tojo (who would become prime minister in October 1941), felt that only one course of action was open to them: war with the United States and the other Western powers—mostly the British, French, and Dutch—who had colonies in Asia and the Pacific.

But it was the United States that represented the most serious threat to Tojo’s goals of conquest and expansion. To neutralize American power and influence in the region—unless diplomatic moves resulted in the United States backing down from its “hostile attitude” toward Japan—Japan’s military leaders would have to seize the initiative and strike a blow from which America would have a difficult time recovering. It would be an immense undertaking, one that would require tremendous sacrifice and effort, and with no assurance of success.

If Japan were not allowed to trade freely with the West, Tojo argued, then Japan, which Tojo and his followers regarded as morally and racially superior to other cultures, would take the resources it needed. Tojo noted, “It goes without saying that when survival is threatened, struggles erupt between peoples, and unfortunate wars between nations result.”

Preparing Yamamoto’s Plans

With the failure of diplomacy almost a foregone conclusion, Tojo moved ever closer to launching a preemptive strike. While Japanese diplomats talked peace in Washington, a large naval task force would allow itself to be seen heading from Japanese home waters toward Southeast Asia—Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong, Dutch East Indies, French Indochina (today Vietnam), and Siam (today Thailand). Thus, while Western eyes were concentrating on this movement (and perhaps even moving assets there to counter any hostilities), another task force would secretly head north and east, aiming at Hawaii. A third force would target the Philippines, which were then an American territory. Swift and violent attacks would be used to decimate American military installations, ships, airfields, and warplanes.

Although racked with internal doubts and conflicts about what he saw coming, Yamamoto felt that as commander in chief of the Combined Fleet, he must obey orders and do his duty–—no matter how wrongheaded those orders were. In January 1941, he began looking for ways that Japan could inflict the greatest damage on the United States while suffering the least amount of pain.

Gradually the tactical concept took shape. A force of six aircraft carriers would steam through the often-stormy waters of the northern Pacific, doing its best to avoid any sea or air patrols. About 200 miles north of Hawaii, the carriers would launch a combined aerial armada of torpedo planes, fighters, and bombers before dawn on a Sunday to catch the Americans at their most vulnerable; dawn attacks have always been the mainstay of military operations.

The attackers would arrive in several waves, each with a specific mission. Midget subs would inflict further damage, and fleet submarines would lurk near Oahu to sink any American ships found coming or going. With a divine grant of fortune, the American fleet would be crippled, American airpower destroyed, and American morale crushed, and within a matter of a couple of hours the attackers would return safely to their carriers, which would then slip away as secretly as they had arrived, safe from counterattack.

At last the Naval General Staff approved Yamamoto’s plan and pilots began training for their secret mission. As the British did before Taranto, the Japanese modified aerial torpedoes to work in the shallow waters of Pearl Harbor. Spies in Hawaii fed Japan with a steady stream of information about what ships were in harbor and where they were berthed.

While the physical assets were being assembled at naval bases across Japan, the personnel, too, were being selected and briefed on the ultrasecret operation. Commander Minoru Genda was named air officer in charge of the aerial assault. His friend, Lt. Cmdr. Mitsuo Fuchida, was appointed to command the First Air Fleet and would lead the initial wave to the target. Only Japan’s most skilled pilots would be chosen to take part.

A relentless period of training and exercises commenced for the aircrews at Kagoshima Bay in southern Kyushu, an area that bore a strong resemblance to Pearl Harbor. Using specially modified aerial torpedoes that would not lodge themselves in the bottom mud of shallow Pearl Harbor, the torpedo-bomber pilots practiced relentlessly. The dive-bombers and high-level bombers, too, dropped hundreds of dummy bombs to perfect their aim. After months of intense training, the Japanese carrier pilots were, without a doubt, the best-trained aviators in the world.

Breaking the Japanese Code

In the meantime, a flurry of messages flew back and forth between Hawaii and Washington, D.C. What the Japanese did not know was that in August 1940, after 18 months of trial and error, American cryptanalysts had finally broken Japan’s fiendishly difficult J-19 diplomatic code (known as “Purple”) by a protocol code-named “Magic.”

Despite this breakthrough, however, the Americans had not yet been able to decipher the codes for Japan’s Army and Navy, nor did many Purple messages lend themselves to easy interpretation—the “winds” messages, for example, which outlined various contingencies for going to war with either the United States, Great Britain, or the Soviet Union, were too obtuse to make much sense.

(After years of trying, the Japanese naval code, dubbed “JN-25” by the American cryptanalysts, was finally cracked in January 1942 by the Combat Intelligence Unit under the command of Commodore John Rochefort working in the basement of the 14th Naval District Administration Building at Pearl Harbor––with the aid of the rudimentary IBM ECM Mark III computer.)

Whenever a new diplomatic message was received, translated, and interpreted, the people at the War Department and Navy Department would send updates to Hawaii; what they thought were alerts and warnings of possible impending hostile action by the Japanese were often viewed by the commanders in Hawaii as being vague and inconclusive, full of unhelpful contradictions and unsupported conclusions. It was no wonder that General Short devoted most of his efforts to preventing sabotage at the island’s military facilities by the local Japanese population rather than preparing to repel an all-out aerial assault.

While Washington seemed to believe its warnings to Hawaii were clear enough, the Army and Navy in Hawaii were fumbling every opportunity to get ready to fend off the coming surprise attack.

Operation Z Underway

While the Kido Butai, the Imperial Japanese Navy “Operation Z” strike force, waited for orders to sail, diplomatic negotiations were reaching a critical point in the U.S. capital. In early November, Japan had sent special envoy Saburo Kurusu, a hard-liner, to Washington to assist the mild-mannered Ambassador Nomura in the negotiations. The two diplomats were instructed to ensure that an agreement (primarily aimed at getting the United States to end its freezing of Japanese assets and back down on its demands that Japanese forces leave China) was signed by November 25. Unknown to Nomura and Kurusu, if the agreement was not reached by then, Japan would give orders for Operation Z to proceed. (The deadline was later pushed back to November 29.)

The United States refused to deal the cards that the Japanese had laid before them, and negotiations appeared to be at an end. Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, head of Kido Butai, received orders to put the plan into motion.

True to expectations, the naval force sent by Japan toward Southeast Asia was spotted and watched intensely by the Western powers. At the end of November, during this bit of deception, the Kido Butai, consisting of six aircraft carriers, two battleships, two heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, nine destroyers, and several oilers, all under Admiral Nagumo, sailed undetected northward from Tankan Bay in the Kuriles, heading for Kwajelain and then the Aleutians.

On December 5, 1941, a Soviet freighter, the Uritsky, bound for Vladivostok from San Francisco, spotted the Japanese fleet. It could have raised an alarm but remained silent; the Soviets, perhaps knowing of Japan’s intentions, had notified the Japanese in advance that the Uritsky would be in the area. The Japanese, for their part, had warned that they would sink any foreign ship they encountered. The Soviets, in turn, said they would declare war on Japan if the transport, loaded with Lend-Lease goods, were fired upon. If allowed safe passage, however, the Russians promised not to alert anyone to the sightings of a Japanese battle fleet in northern Pacific waters.

Aboard his flagship, the battleship Akagi, Admiral Nagumo lifted the veil of secrecy and announced to the captains of the task force’s ships that Japan, unless it received a last-minute recall message from Tokyo, was going to war with the United States and that the fate of the empire rested on the success of every man involved in the mission. The message was then delivered by the captains to the crews of their various ships.

To underscore the importance of the mission, on December 6 Nagumo ordered that the Imperial Japanese Navy’s most precious relic—the flag that had flown over Admiral Togo’s ship during the 1905 victory over Russia at the battle of Tsu-Shima––be raised above the Akagi.

A disturbing bit of information then arrived; intelligence reported that none of the five U.S. carriers were at Pearl Harbor. Although disappointed, Nagumo did not let the news cause him to cancel or delay the attack. The fact that plenty of battleships and cruisers and destroyers were in harbor was reason enough to proceed as planned. Signal officers stood near their radio sets to listen for the “recall” message, just in case.

At this point, however, the historic waters get muddy. Some sources say that it became obvious that Pearl Harbor was the target of an intended Japanese attack and that President Roosevelt and others close to him pretended not to know in order to ensure American involvement in the war, while others say the opposite.

At any rate, Ambassadors Nomura and Kurusu were waiting at the Japanese embassy in Washington on that fateful Sunday, December 7, for instructions to arrive from Japan. The instructions were delayed, then had to be decoded, translated, and typed in English. By the time Nomura and Kurusu were ready to meet with Secretary of State Hull, the strike force was in the air, approaching the island of Oahu.

Nagumo’s Kido Butai had taken up station 230 miles north of Oahu early on December 7. Radio silence was total; communication between ships was conducted by lamps and flags. Preparations were then made for the launch. The planes were fueled and loaded with bombs, torpedoes, and machine-gun ammunition. Pilots solemnly said good-bye to each other and to their crews on the carriers’ decks. The mechanics and armorers presented their pilots with hachimaki––the traditional white headbands decorated with the red “rising sun” symbol and inspirational slogans written in kanji characters––and wished them well on their journey.

Tora Tora Tora

The strike force was launched just before dawn, with 43 Mitsubishi A6M2 “Zero” fighters lifting off to provide cover over the fleet while the rest of the first wave––89 Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” level bombers and 51 Aichi D3A2 “Val” dive-bombers––took off and assembled in midair. With the first wave launched, the crews on the carriers hustled to bring the second wave up to the flight decks on elevators.

Flying in the lead plane over black waters, Commander Mitsuo Fuchida was nervous, his mind and body in a heightened state of readiness. Did the Americans know that he and his men were coming? Would they meet a wall of American planes as they approached Oahu? Would the crews on the ships at Pearl Harbor be on the alert, ready to fill the sky with anti-aircraft munitions? He did not know, and he needed to know because it would dictate which of Genda’s attack patterns would be employed. If surprise were gained, Fuchida would fire one “Black Dragon” flare indicating that the torpedo bombers were to lead the attack. If the Americans were on the alert, he would fire two flares, indicating that surprise had been lost and that the fighters were to go in first.

Somehow the signals got botched. As he approached Oahu, Fuchida mistakenly thought that the fighters had missed the first “one flare” signal, so he fired another flare for their benefit. But the torpedo bomber pilots had seen the first flare and then the second and thought it meant that surprise had been lost and fell back in the formation.

In the end, the mix-up in signals made no difference. As Fuchida glided above Pearl Harbor, he saw that the sky was clear of American planes and the decks and AA gun tubs of the ships below appeared to be empty. At 7:53 he transmitted the success signal—Tora, Tora, Tora (“Tiger, Tiger, Tiger”)––back to the fleet. His planes banked into the attack.

Just minutes before, an unsuspecting Captain Howard D. Bode, commander of the battleship Oklahoma, had left the ship for liberty and was being carried to shore by a launch; he had left Commander Jesse L. Kenworthy, Jr., in charge during his absence.

One of the first Americans to become aware of the attack was Rear Admiral William R. Furlong, whose quarters were aboard the old minelayer Oglala, berthed at 1010 Dock across the channel from the southeast side of Ford Island. He saw the initial flight of aircraft, assumed they were American, and cursed the pilot who was careless enough to allow an unsecured bomb to fall from his undercarriage and explode on the island. Moments later, Furlong saw the red ball insignia on the plane’s fuselage. He sounded the attack alarm and ordered all ships at Pearl to sortie. For most it was too late.

The First Bombs on Pearl Harbor

The first to feel the bombs was the Naval Air Station at Ford Island. Next came the airfields at Hickam, Wheeler, Bellows, Ewa, and Kaneohe; Genda knew that if the first attacking wave could knock out the American planes before they could get airborne, his pilots would have unfettered access to the ships anchored in the harbor and would only need to worry about the AA fire.

In Pearl Harbor, author H.P. Willmot wrote, “At the time of the attack, there were 394 aircraft on Oahu, of which 139 Army and 157 Navy aircraft were operational. Of these only 88 were fighters, but such was the fury and violence of the assault that only a handful of them were able to try to get into the air to give battle on equal terms.”

American pilots tried their best to scramble their planes and to get airborne to battle the Japanese formations, but almost all their efforts were in vain. The Kaneohe Naval Air Station was hard hit, with all 33 of its aircraft destroyed on the ground. At Ewa, located west of the entrance to Pearl Harbor, 33 of the 49 aircraft stationed there were destroyed or disabled. At Wheeler, Hickam, and Bellows Army Airfields, 77 planes were knocked out in a matter of minutes. By the time the attacks on the airfields were over, 164 American aircraft had been destroyed and another 129 damaged, although some estimates are even higher.

At Haleiwa Fighter Strip, northwest of Honolulu at Kaiaka Bay, a small group of American pilots of the 47th Pursuit Squadron drove wildly in two cars from Wheeler Field, dodged strafing bullets along the way, jumped into their P-40s, and took off. Second Lt. George Welch scored four victories, while Kenneth Taylor and three other pilots downed three additional Japanese aircraft; some reports had Army pilots shooting down as many as 12 planes. Both Taylor and Welch would be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

While the airfields were being hit, other planes went after Schofield Barracks, bombing and strafing the installation while American soldiers ran around in panic, searching for weapons and ammunition with which to fight back.

During this period, Fuchida’s high-altitude bombers, torpedo planes, and divebombers directed their attention toward the ships, many of which were lined up like fat sitting ducks along Battleship Row on Ford Island’s southeast side.

But the first ship to be attacked was Utah, an old battleship that had been planked over and converted into a gunnery training ship, moored on the opposite side of Ford Island at F11. She looked to the Japanese pilots like an aircraft carrier and soon caught the brunt of the attack, along with the cruiser Raleigh. The enemy pilots slammed two torpedoes into Utah, causing her to almost immediately capsize. The attack killed at least 54 men, who still remain entombed within her.

At Battleship Row, the torpedo planes came in low and launched their fish. West Virginia was hit at 7:57 by Lieutenant Murata Shigeharu; Lieutenant Jinichi Goto, leading a second column of torpedo planes, set his sights on nearby Oklahoma, moored at F5 inboard of Maryland. He and another pilot both struck home. These were followed by further attacks, and soon Oklahoma was ablaze and listing badly. At 8:00, a torpedo penetrated the hull amidships near frame 65 and an enormous belch of flame rocked every inch of her.

The scene aboard Oklahoma was sheer bedlam. Sailors were running everywhere, some trying to get to their battle stations, some trying to get below to escape flaming fuel oil and flying ordnance, others jumping overboard. Kenworthy gave the order to abandon ship, but it was too late. The ship quickly keeled over, dooming more than 400 sailors trapped within her.

As the Japanese planes continued swooping in and dropping more bombs and torpedoes, alarms were going off all over the harbor. Men barely awake and in various conditions of undress were suddenly energized by bursts of adrenaline and sprinted for their guns, retrieving the anti-aircraft and machine-gun ammunition, quickly loading, and peppering the sky that was now swarming with enemy planes.

One pilot, streaking low across Ford Island, took aim at Pennsylvania, moored in dry dock. But, seeing that the mooring slip would block his missile’s path, he diverted his flight toward nearby Oglala. His aerial torpedo went too deep, slipped under Oglala’s hull, and slammed into the light cruiser Helena, tied up inboard of her; the subsequent explosions wrecked both ships.

“This is No Drill”

While all this was happening, Admiral Kimmel, at his office at CinCPac headquarters, was, incredibly, being briefed over the phone by Commander Vincent Murphy about Ward’s attack on a mystery sub when a breathless courier rushed into Murphy’s office with a report on the obvious: “Sir, there’s a message from the signal tower, saying the Japanese are attacking Pearl Harbor and this is no drill!”

Indeed. At the Pacific Fleet’s Message Center, the word was already going out: “Air raid on Pearl Harbor X This is no drill.”

The battleship Pennsylvania was in a somewhat protected position––in Dry Dock No. 1, with the destroyers Cassin and Downes docked at her head and the submarine Cachelot at her stern; three spaces away in another dry dock was the destroyer Shaw.

Bill Trimmer was a 23-year-old Electrician Third Class aboard Pennsylvania. At about 7:50 on the morning of December 7, he went below to the electrical shop on the third deck for muster at his duty station. “I had just gotten into the shop,” he said, “when the PA system came on, sounding ‘General quarters, air defense, and this is no drill!’ A lot of background noise of planes roaring and bombs exploding could be heard.”

Trimmer took off running for his battle station on the fifth deck in the forward distribution room, where he donned headphones that connected him to the battleship’s various electrical departments.

At precisely 8:00 am, a flight of 18 aircraft from the carrier Enterprise, at sea 200 miles to the west, arrived over Oahu, planning to land at Ford Island, and flew into the maelstrom. Radioing back to the ship, the pilots told the carrier what was happening and the ship’s skipper, George D. Murray, changed course and headed west, out of range of any potential attackers.

The Big E’s pilots, however, were caught in the battle over Pearl. Gunners on ship and shore did not bother to first check the identity of the new arrivals; they simply continued blasting away at anything that had wings, assuming all were foes. Several were shot down in the melee. One of the Enterprise pilots, Ensign Manuel Gonzales, radioed, “Please don’t shoot! Don’t shoot! This is an American plane.” Moments later, he ordered his aircrewman, Leonard J. Kozelek, to bail out: neither man was ever heard from again.

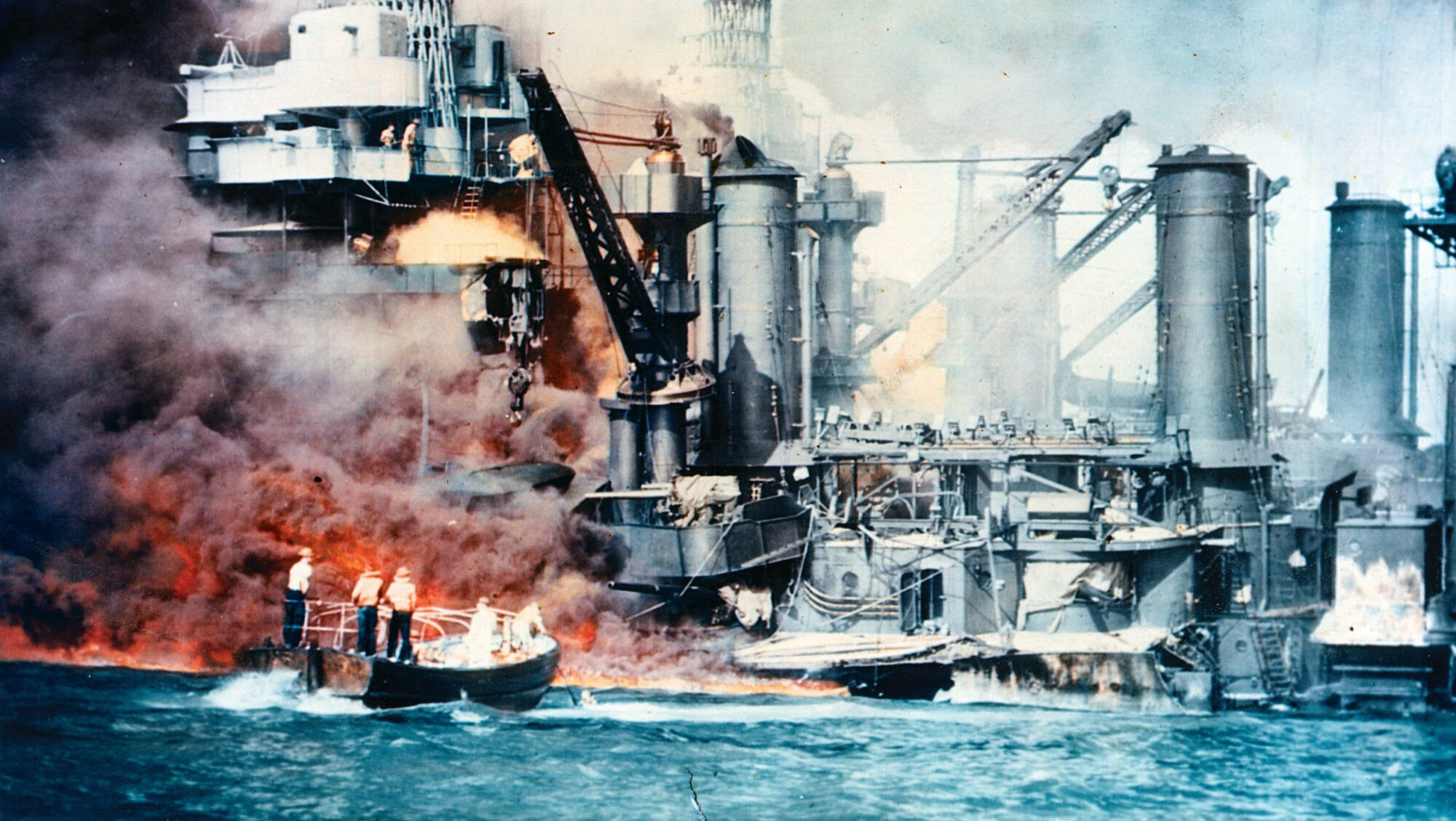

Shortly after 8:00, the USS Arizona, tied to her mooring F7, caught the attention of the torpedo planes. Although aging, the 29,000-ton Arizona was still a powerful symbol of American naval might and a prime target of the Japanese, but, although protected outboard by Vestal, she was still not immune to the torpedoes; one slid under Vestal and slammed into her hull.

At 8:05, California, tied up alone at berth F3, was struck by two aerial torpedoes. The ship’s hatches were open, awaiting a full inspection, and allowed torrents of water to pour in; she quickly sank with just her superstructure protruding from the water.

Then the high-altitude bombers came over with their deadly ordnance. One bomb hit Arizona’s boat deck between the No. 4 and No. 6 guns, splitting the deck wide open and touching off fires. Men rushed with hoses to fight the flames, but with no water pressure, they were helpless.

At 8:10 came the coup de grace for Arizona. A dive-bomber pilot, Tadashi Kusumi, and his bombardier, Noburu Kanai, took aim. Their lone Type 99 bomb struck near the No. 2 turret and exploded in the forward magazines full of shells for the 14-inch guns. Suddenly the old ship detonated in a terrible fireball and shockwave, throwing debris and pieces of sailors hundreds of feet into the air. Gone in an instant were 1,177 of her crew and Marine detachment, along with her skipper, Captain Franklin van Falkenburgh and Rear Admiral Isaac Kidd, both of whom had been on the bridge. Burning oil flared out from her, and the badly damaged Vestal was quickly tugged out of harm’s way.

Two bombs also found Tennessee and West Virginia at F6, causing both to sink. A whirling piece of jagged debris from the exploding Tennessee scythed through the air and into the bridge of West Virginia, disemboweling her captain, Mervyn Bennion. Doris “Dorie” Miller, an African American cook aboard West Virginia, carried wounded sailors to safety, then tried to help his dying captain. When that proved impossible, he rushed to a .50-caliber machine gun and blazed away until ordered to abandon ship. For his courage, Miller was awarded the Navy Cross.

Commander Fuchida, circling high above the devastation, recalled, “By 8:00 there were no enemy planes in the air…. While my group circled for another attempt, others made their runs, some trying as many as three before succeeding. We were about to make our second bombing run when there was a colossal explosion in Battleship Row [the Arizona]. A huge column of dark red smoke rose to 3,000 feet. It must have been the explosion of a ship’s powder magazine. The shock was felt even in my plane, several miles away.”

Focusing Fire on the Nevada

In far-off Washington, D.C., the shock was about to be felt there. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was in his White House study with adviser Harry Hopkins in the early afternoon when Frank Knox, Secretary of the Navy, phoned. “Mr. President,” Knox said, “it looks like the Japanese have attacked Pearl Harbor.” As Doris Kearns Goodwin noted in No Ordinary Time, “Hopkins said there must be some mistake; the Japanese would never attack Pearl Harbor. But the president reckoned it was probably true—it was just the kind of thing the Japanese would do at the very moment they were discussing peace in the Pacific. All doubt was settled a few minutes later when Admiral [Harold] Stark [head of the U.S. Navy] called to confirm the attack.”

Back in Hawaii, the nightmare was continuing. The flight of a dozen unarmed B-17s that Lieutenant Tyler mistakenly assumed were represented by the earlier radar sighting suddenly arrived in the midst of the battle. Originally scheduled to land at Hickam, the flight leader told his pilots to land anywhere they could. All of the planes were attacked and hit, but only one was lost.

All along Battleship Row, ship after ship was exploding, burning, dying. Nevada, moored alone at F8 at the northeast end of the row, had been under partial steam and she, along with five destroyers, was able to get underway. Her skipper, Captain Francis W. Scanland, was ashore that morning, so Lt. Cmdr. Francis Thomas was at the helm as she made her way south to the exit channel.

Seeing Nevada making a run for it, the Japanese descended upon her like hawks on a field mouse, hoping to sink her in the channel and bottle up the harbor. Bombs crashed all around her, but the ship’s gunners engaged in a running gun battle with the attackers, downing three of them.

Suffering from a huge torpedo wound, Nevada, listing to port and down at the head, was slowing. Then someone on the bridge spotted signal flags that had been raised at the Naval District Headquarters, ordering the ship to stay clear of the channel. So Thomas swung her in a wide arc and backed her into the shore on the Waipio Peninsula across from Hospital Point.

Dead in the water and ablaze, Nevada continued to attract a crowd and received a further pummeling. The old girl then settled onto the bottom of the shallow harbor (where she would remain for the next two months while repairs were being made; she would fight again in support of the Allied landings in Normandy in June 1944). Of her crew of nearly 1,500, 50 officers and men died on her on December 7, and 109 were wounded.

At 8:17, the destroyer Helm, the first ship to get underway that morning, had reached the harbor entrance and encountered another midget sub outside. Although contact was lost, Helm radioed her sighting to the fleet. At 8:30, the destroyers Breese and Monaghan, and the seaplane tender Curtiss and repair ship Medusa, saw another sub and went into the attack, sinking it with deck-gun fire and depth charges.

Bill Trimmer on the Pennsylvania

The Japanese attack was building in intensity. At 8:40 am, the second echelon, a flight of high-level horizontal bombers from the carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, led by Lt. Cmdr. Shigekazu Shimazaki and Lieutenant Tatsuo Ichihara, arrived over smoke-shrouded Pearl Harbor. Their mission was to bomb the hangars and other permanent facilities at Hickam Field and elsewhere; despite the smoke, their bombardiers’ aim was true and they inflicted much damage. Even the naval hospital was not spared.

Curtiss was then hit by a bomb that exploded on her main deck, killing 20 and wounding another 58. Still in the fight, though, her gunners zeroed in on another bomber that crashed into one of her big topside cranes and exploded but caused only minor damage to the ship.

The “Kate” dive-bombers, too, were still engaged in their deadly business, dropping their 250-pound eggs––whenever the pilots could glimpse their targets through the thick, roiling smoke––on whatever ships seemed to be the least damaged.

The Americans were now peppering the air with munitions of all types; the bombers had to fly through a thick storm of lead and steel being thrown up at them. Gunners on Maryland and Helena downed three of the attackers, and those on other ships chalked up further scores. Fuchida reported, “Enemy anti-aircraft fire began to concentrate on us. Dark gray puffs burst all around. Most of them came from the ships’ batteries, but land batteries were also active.”

Throughout the harbor, chaos and casualties continued to mount. At about 9:00, dive-bombers struck Pennsylvania in dry dock. Bill Trimmer, aboard the immobilized battleship, recalled, “A bomb blew our power lines in two. All the lights went out and all the machinery stopped running. It was pitch dark until we turned on our battle lanterns––large, battery-powered lights. Our emergency lights then came on, taking their power from batteries. They were very dim, but better than the battle lanterns.

“I could hear all kinds of reports coming over the headphones, such as, ‘There goes the Cassin, the Downes, the Oklahoma, the California, and the West Virginia.’ I’m reporting all this to our chief, a man named Moorehouse. There was a little humor down there when one of the men asked Chief Moorehouse, in all sincerity, if he thought this would make the papers back in the States. The Chief said, ‘I guess so.’

“It was about this time that I felt the ship shudder and a loud boom come from starboard aft. We had been hit with a 500-pound bomb that penetrated two-and-a-half decks and exploded.”

Trimmer asked permission to go topside for a look around; Moorehouse granted the request. Coming up during the brief lull between attack waves, Trimmer was greeted by scenes of utter devastation. The destroyers Downes and Cassin, resting in the same dry dock as Pennsylvania, were shattered wrecks engulfed in flame. Within the dry dock and beyond, the water was covered with a carpet of floating debris. Ships of all description were burning, listing, capsizing, sinking. Sailors young and old were in the water, some hurt, some burned, all swimming for their lives.

Trimmer said, “I was feeling so helpless knowing I couldn’t reach them; to jump in to help, I would just become another victim. Other sailors worked frantically everywhere to douse the fires and prepare for a follow-up attack, which was not long in coming.”

Trimmer was right. As Pennsylvania’s anti-aircraft guns opened up on the next wave of onrushing planes, he “flopped face down on the six-foot-wide starboard catwalk, looking to where our gunners were shooting at a Japanese torpedo plane. The pilot was flying very slow and low. As they say in basketball, I thought he had ‘good hang time.’ The plane was low—about 100 feet—and about 50 yards down the starboard side of our ship. The plane had dropped its torpedo and was flying with its rear gunner strafing anything he could. I could see his machine gun firing at the anti-aircraft guns just above me. At that time I was hit in the head and shoulder with fragments and thought I was going to die.”

Trimmer’s wounds were not as serious as he first feared, and he scrambled to the ship’s stern, where he encountered scenes of horror. “I saw one kid that had been hit laying there, and I pulled him up under Number Three turret and went to help others. I left the boat deck to go down to the afterdeck, where they were bringing out the dead and wounded. I helped with this and won’t ever write about it because it was so gruesome. I also tried to help fight the fire caused by the bomb. I didn’t have a mask and the fumes were heavy, so I couldn’t do much.”

Not far from Pennsylvania was the destroyer Shaw, held in Floating Dry Dock No. 2. At 9:12, a quick succession of three bombs penetrated her fuel tanks, which then, at 9:30, touched off Shaw’s forward magazine and caused a giant belch of fire, smoke, and flying debris.

Japan’s Devastating Victory

The Japanese pilots, searching for more targets, found them away from Battleship Row. The destroyer tender Dobbin, moored at the north end of Ford Island, came under attack and was blasted unmercifully. The cruisers Honolulu and St. Louis, docked at the Southeast Loch’s finger piers, were attempting to make steam and get underway, but an explosion crippled Honolulu. St. Louis somehow managed to escape and was moving by 9:31 past all the flaming wreckage of the harbor, heading toward the exit channel. Miraculously, she made it to open water––and even hit and sank the fourth of five midget submarines lost by the Japanese.

Military personnel weren’t the only ones to suffer, for what goes up must come down. In Honolulu, Pearl City, Red Hill, Ewa, Wahiawa, Waipahu, and elsewhere, the anti-aircraft ammunition that was fired at the Japanese planes and missed began raining down with deadly effect. Off-target Japanese bombs also took their toll. Thirty-two civilians were killed in Honolulu, with the worst mass casualties occurring at the intersection of Kukui Street and Nuuanu Avenue. A shell dropped onto a restaurant there, killing the Japanese-American owner, his three children, and another relative, along with seven diners having breakfast. A bomb exploded at Judd and Iholena Streets, killing three members of the McCabe family in a car while on their way home from church. The final civilian death toll was reported as 69.

By the time the attack ended, 2,403 American soldiers and sailors were dead or missing, and 1,178 more lay wounded. The most devastating attack in American military history was over by 9:45 as the Japanese pilots headed north to their awaiting carriers.

It had been a tremendous victory. More than 30 American warships had been either sunk or damaged to varying degrees. The American air force in Hawaii was all but wiped out—all at a cost of just 29 aircraft, five midget submarines and one large submarine, and 65 men.

In the face of great disaster came great heroism. For their actions on December 7, 1941, 15 men would receive the Medal of Honor, making that day’s total unique in the history of America’s highest military decoration: Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd (USS Arizona, posthumous), Captain Mervyn S. Bennion (West Virginia, posthumous), Captain Samuel G. Fuqua (Arizona), Captain Franklin van Falkenburgh (Arizona, posthumous), Commander Cassin Young (Vestal), Lieutenant John W. Finn (Kaneohe Naval Air Station), Lieutenant Jackson Pharris (California), Ensign Francis C. Flaherty (Oklahoma, posthumous), Ensign Herbert C. Jones (California, posthumous), Warrant Officer Thomas Reeves (California, posthumous), Chief Boatswain Edwin J. Hill (Nevada, posthumous), Machinist’s Mate Robert R. Scott (California, posthumous), Chief Watertender Peter Tomich (Utah, posthumous), Machinist Donald K. Ross (Nevada), and Seaman James Ward (Oklahoma, posthumous).

When they landed back on their carriers’ decks, many of the Japanese pilots were bursting with enthusiasm and eagerness to return for another strike. There were still plenty of targets to be hit—especially the fuel farms, submarine pens, and shore installations, not to mention the absent American carriers—but Admiral Nagumo said no. The task force must return to Japan before the Americans could locate it; the carriers and other ships would be needed for further operations in the event that the United States failed to capitulate. Incredulous, many in Genda’s air staff tried to get the admiral to change his mind but it was no use. Kido Butai would return to Japan immediately.

Nomura’s Ignorance of the Attack

In Washington at 2:40 pm, Ambassador Nomura knew none of this by the time he and special envoy Kurusu were ushered into Hull’s office carrying the long-delayed translation of the final part of Japan’s message—the part that said that, in light of America’s intransigence, Japan was breaking off diplomatic efforts to reach a consensus and that war was likely to follow—a message that Hull had already read, thanks to the Magic intercepts.

Once in Hull’s office, Nomura and Kurusu were not offered chairs. Instead, Hull, burning with a barely contained fury, told them, “I must say that in all my conversations with you during the last nine months, I have never uttered one word of untruth. This is borne out absolutely by the record. In all my 50 years of public service I have never seen a document that was so crowded with falsehoods and distortions––infamous falsehoods and distortions on a scale so huge that I never imagined until today that any government on this planet was capable of uttering them.”

Then, with a nod of his head toward the door, Hull dismissed the Japanese representatives. Hurt and puzzled, Nomura did not learn until he returned to his office that his country had already struck the first blow.

The Roberts Commission

Two days after the bombs stopped falling, the recriminations and hunt for scapegoats began. On December 9, Navy Secretary Knox flew to Oahu to initiate his own investigation; Kimmel told him that, contrary to Washington’s belief, he had received no warning of a possible attack until the attack was already underway.

Courts of inquiry and formal hearings (the “Roberts Commission”) began in late 1941, and both Kimmel and Short were ultimately held responsible for “dereliction of duty;” both officers retired in February 1942, and both would request courts-martial as a way of clearing their names. Further congressional hearings would take place.

Roosevelt’s role was not seriously scrutinized at the time but has since been the subject of criticism and charges of collusion in order to get America into the war. Several books and magazine articles have attempted to put the blame directly on the president’s shoulders and to claim that a conspiracy and cover-up were then at play. (See the sidebar by Donald M. Goldstein.)

Patrick N.L. Bellinger, who had been in command of all scouting aircraft in the Pacific Fleet, later called the attack on Pearl Harbor “a deep-eyed deliberate plan to get this country into war with Japan and Germany by needling the Japanese into making the first war move…. In my opinion, Roosevelt and his cohorts criminally failed to keep Admiral Kimmel informed of information that was available—information that the simplest mind would have known was of vital importance to the protection of the Pacific Fleet.”

Whether this was true or not still remains, after 70 years, a matter of intense speculation and debate. Beyond dispute, however, is the fact that America’s involvement in the war led to the ultimate defeat of the Axis powers, ushered in a new world order, and quite literally saved the free world from destruction at the hands of the Germans and Japanese.

As Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson noted later on December 7, “When the news first came that Japan had attacked us, my first feeling was of relief that the indecision was over and that a crisis had come in a way which would unite all our people…. For I feel that this country united has practically nothing to fear while the apathy and divisions stirred up by unpatriotic men have been hitherto very discouraging.”

Awakening a Sleeping Giant

Instead of causing the United States to retreat and allow Japan unfettered rampage throughout Asia and the Pacific, as Tojo predicted, the exact opposite happened. No longer isolationist or “neutral,” America and the American industrial machine, although idled by the Great Depression, began turning out military goods at an unprecedented rate, while millions of aroused Americans rushed to recruiting offices to prepare themselves for a fight to the death with the country’s enemies.

Although Yamamoto is widely (and erroneously) quoted as having said after the Pearl Harbor raid, “I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve,” Yamamoto’s actual words were written to Ogata Taketora, the ultra-nationalist editor of the Tokyo newspaper Asahi Shimbun on January 9, 1942: “A military man can scarcely pride himself on having ‘smitten a sleeping enemy’; it is more a matter of shame, simply, for the one smitten. I would rather you made your appraisal after seeing what the enemy does, since it is certain that, angered and outraged, he will soon launch a determined counterattack.”

Yamamoto was certainly correct. And he would not live to see the end of the war that he and his country’s leaders, along with Adolf Hitler, had provoked––a war that caused the deaths of 50 million people and changed forever the course of world history.

Minor error: “Aboard his flagship, the battleship Akagi…” should have read aircraft carrier, not battleship. IIRC, the ship was converted from a battle cruiser.

Super article but nothing new

Agreed. The story needs to be told again considering current events in the region.

A comment on English in the title: What is the origin of the so-called word “Awoken” in the title?! The real word is “Awakened”.

The deceit, treachery, and incompetence of the US government and military leadership, including Roosevelt, Stimson, Navy Secretary Knox and General Marshall lost 3000 American lives tragically and unnecessarily. That should also go down in infamy.