By Kevin M. Hymell

Shortly after 8 am on June 6, 1944, a German officer overlooking the Vierville-sur-Mer Draw on Omaha Beach reported that the soldiers defending the beach were repelling the Americans: “The enemy is in search of cover behind the coastal zone obstacles. A great many motor vehicles—and among these ten tanks—stand burning at the beach. The obstacle demolition squads have given up their activity. Debarkation from the landing boats has ceased; the boats keep further seawards.… A great many wounded and dead lie on the beach.”

But there was one caveat in this upbeat message: “Some of our strong points have ceased firing; they do not answer any longer when rung up on the telephone.”

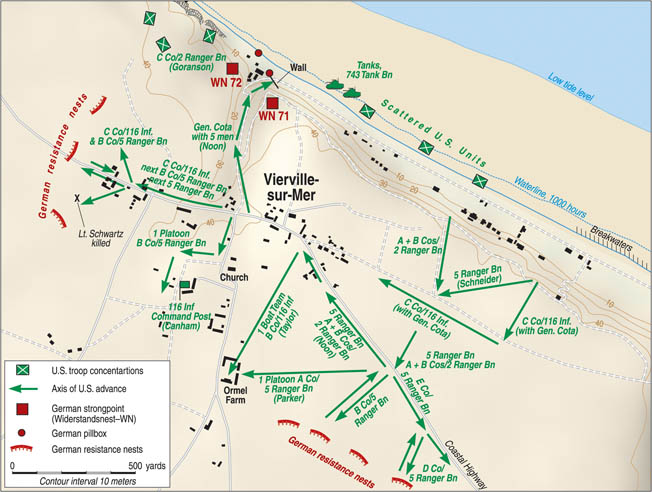

The Vierville-sur-Mer Draw, a road that cut between the cliffs overlooking Omaha Beach, was the Americans’ most important objective within the four-mile-long, crescent-shaped shoreline. Of the five draws leading inland, only the Vierville Draw possessed a paved road, the best option for getting armor and vehicles off the beach. The road ran almost the length of the beach then turned south through the draw and continued into the small town of Vierville-sur-Mer. The hard-surfaced road eventually joined the coastal highway, offering high-speed connections to Utah Beach to the west and to the British and Canadian beachheads to the east. The Germans also understood the draw’s importance and built strong defenses to defeat a direct Allied assault.

Pillboxes stood on either side of the draw while a third blocked its entrance from the beach. The pillbox on the east side included an 88mm cannon, while the one on the west side housed a French 7.5cm KF 231(f) cannon. The pillbox in the center housed a 50mm gun. Atop the cliffs on either side of the draw were formidable independent strongpoints called Widerstandsnests (WN), each manned by two squads, usually armed with machine guns and mortars. WN 71 stood on the east and WN 72 stood on the west. A third WN, designated 73, stood 200 yards west of WN 72. A fortified house stood in front of WN 73. Most of the German defensive positions fired across the beach, not out to sea, ensuring that the German gunners had enfilading fire on assaulting troops.

Between the beach and the pillboxes ran a 21-foot-high sloped seawall topped with coils of barbed wire. The beach at low tide spanned more than 400 yards, most of which was covered with Belgian gates (anti-tank steel gates), mines atop angled logs so landing craft would snag them and explode, and Czech hedgehogs (angled iron antitank obstacles). The beach, the road, and the sloping cliff bluffs were all seeded with mines. Mortar positions were dug in behind the bluffs. To prevent vehicles from using the exit, the Germans also built two concrete walls, measuring 125 feet long, nine feet high, and six feet thick. The Americans needed to destroy both walls if they hoped to move their armor off the beach.

General Leonard “Gee” Gerow, the V Corps commander responsible for Omaha Beach, intended to give his soldiers the firepower and support they needed to crack the Vierville Draw. He and his staff designated the beaches west-to-east in front of draw as Charlie, Dog Green and Dog White. The plan of attack called for DD tanks (amphibious tanks driven by propellers and surrounded by canvas skirts) and tanks of the 743rd Tank Battalion, delivered by Landing Craft Tanks (Armored) [LCT(A)s], to land first at Dog Green, followed by the infantry.

The task of capturing the draw went to Lt. Col. John Metcalfe’s 1st Battalion, 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division. The regiment, a National Guard unit, traced its lineage to Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson’s Stonewall Brigade. Soldiers from Virginia made up most of the unit, while men from Delaware and Maryland–– many of whom had drilled together long before the unit was federalized in 1941––comprised the remainder. The men, calling themselves the “Stonewallers,” wore a distinctive blue and gray yin yang symbol on their helmets and left sleeves, a symbol of post-Civil War unity between the North and the South.

According to the plan, the Stonewallers’ Company A would land on Dog Green Beach directly in front of the draw at 6:30 am. Simultaneously, Company G would land on Company A’s left, east of the company, with F and E Companies landing farther east on Dog White, allowing all the companies to support each other. Charlie Beach, to the right of A Company, was designated for a company of Rangers.

Seven minutes after Company A’s assault, demolition teams from both the 121st and the 146th Engineer Combat Battalions were to land and blow up obstacles, clearing a path for the follow-on forces. The rest of 1st Battalion—Companies B, D, and C—would follow behind Company A at 7 am. Within a half hour, two field artillery battalions would land via amphibious trucks known as DUKWs.

The company of Rangers landing on Charlie Beach was called Ranger Force B, and consisted of Captain Ralph Goranson’s Company C of the 2nd Ranger Battalion. Their mission was to capture Pointe de la Percée, a rock cliff between Omaha Beach and Pointe du Hoc to the west. Ranger Force C, consisting of Lt. Col. Max Schneider’s 5th Ranger Battalion and Companies A and B of the 2nd Ranger Battalion, would be used as a reserve force for the draw, if they were not needed at Point du Hoc, which would be under assault by Lt. Col. James Rudder leading Ranger Force A.

The Opening Assault

The Allied plan broke down almost immediately. In the predawn darkness the LCT(A)s transporting the tanks scattered and could not reorganize, forcing the infantry to land without heavy fire support. Further hampering the landings, naval preparatory salvos set fire to the grass on the sloping bluffs, obscuring distinctive landmarks, such as Vierville’s church steeple. On board the landing craft, rough seas drenched the soldiers, making many seasick. The landing plan further unraveled when three landing craft, an LCT(A), and two infantry landing craft sank on the way into shore.

The strong current and grass fires pushed landing craft east and impeded visual navigation for the follow-up units. Companies G and F, 2nd Battalion, 116th Infantry, which were supposed to land adjacent to A’s left flank, landed so far to the east that A Company’s soldiers could not see them; the soldiers of Company G raced off their landing craft and were surprised to find themselves at the Les Moulins Draw. A few amphibious tanks landed simultaneously and were masked by smoke, saving the unit from accurate enemy fire. Meanwhile, Company A landed on schedule, 6:30 am, at the right place, Dog Green Beach, without the benefit of covering smoke and completely alone.

Six British Landing Craft Assault (LCAs) carried Company A into battle. Their armored doors, fixed onto the front ramps, allowed only a single soldier at a time to exit, unlike the American LCVP (Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel), which allowed three columns to exit together. Captain Taylor Fellers, the company commander, led the men from his craft directly in front of two pillboxes protecting the draw. Inaccurate enemy mortar rounds fell all around as they waded to the beach. The men crawled forward, staying ahead of the rapidly incoming tide. Suddenly, German machine guns raked the beach, killing Feller and all 31 men in his LCA.

The Germans then brought other landing craft under fire. Gunners targeted the craft exit ramps as they fell, killing the men as they charged forward. For the enemy, it was a shooting gallery. Laden with equipment and holding their rifles above their heads, the Americans were slow-moving targets. Some men drowned immediately after plunging off the ramp. Pfc. Gil Murdock jumped into water over his head. He inflated his life preserver belt and resurfaced, only to realize that his landing craft had backed away and was making another run at the beach, with the ramp still lowered. The ramp knocked Murdock under water. When he resurfaced a second time, he grabbed the back bumper of the craft and rode it to the beach.

Those who made it out of the water sprinted across the beach toward the seawall. Some dropped behind the German obstacles for protection. Dead and wounded men filled the beach. Men screamed at others to take cover, but their voices were drowned out by enemy fire. A soldier with a gaping hole in his head and clutching rosary beads stumbled forward and knelt in the sand to pray, only to be cut in half by German machine-gun fire.

A bullet caught Lieutenant Edward Tidrick in the head, knocking him into the sand. He raised himself up and, despite blood flowing from his throat, ordered, “Advance the wire cutters!” Those were his last words. German machine-gun fire stitched him from head to waist.

The men scrambled to stay alive along the seawall, but with enemy machine guns firing parallel to the beach and snipers dominating the high ground, the Americans found little safety. Men who escaped drowning when their landing craft deposited them too far from shore were killed while they tried to climb over the seawall or hide behind it. Those still alive felt alone, surrounded by so many dead bodies. The Germans killed more than 100 of Company A’s 155 soldiers.

An LCT(A) landed simultaneously with Company A and immediately drew mortar and machine-gun fire. The ramp dropped and three tanks from the 743rd Tank Battalion rolled onto the beach, joining two DD tanks that had made it ashore. The Germans immediately knocked out one of the DD tanks; its dead commander hung from the turret hatch, but the other tank continued to maneuver and fire. The Germans dropped a round on the LCT(A)’s ramp, ripping it off.

Some of the infantrymen took refuge behind the tanks, but with the draw still defended, the tanks had little room to maneuver. Some of the tanks had to roll over the dead bodies of the infantrymen to survive. “The saddest relic of that advance,” recalled Corporal William Preston, “was an almost entire pair of Army-issue long johns that remained entangled for days on one of our tank’s tracks.”

Tanks that managed to stay out of the line of fire from the 88 were still exposed to other German guns. The tanks fired tracers at the pillboxes to mark them for Navy cruisers, which shelled the targets. The tanks that survived the opening round roared back to the waterline where they plowed back and forth in the surf firing at enemy positions.

The Rangers of Captain Ralph Goranson’s C Company fared better than the Stonewallers. They came ashore on Charlie Beach, just east of the Vierville Draw. Goranson had two plans for the assault. Plan One called for exiting through the draw, which the Stonewallers would have cleared. Plan Two called for scaling the cliffs of Charlie Beach, a difficult task since his Rangers lacked the specialized scaling equipment possessed by the Rangers assaulting Pointe du Hoc. He would only resort to Plan Two if the Germans still controlled the draw.

As Goranson’s 65 Rangers approached the beach, enemy small arms and artillery fire splashed the water around their two landing craft. The men charged out of their boat, waded ashore, and struggled up the rocky beach as fast as their equipment allowed, all while under heavy German fire. As Goranson ran off his LCA, a German 88 shell exploded on the ramp, ripping it off. Another round tore into the center of the LCA. A mortar round that threw Lieutenant Sidney Salomon forward as he ran up the beach killed most of the men behind him. When enemy machine-gun fire began stitching the sand in front Salomon, he jumped up and ran for the safety of the cliff wall. By the time the stunned survivors reached the base of the cliff, they realized their numbers had been cut in half.

At the cliff base Lieutenant William Moody looked at Captain Goranson and asked, “Plan Two?” Goranson responded, “Right.” Suddenly, a Ranger shouted out, “Mashed potatoes! Mashed Potatoes!” No one knew what he meant until a German grenade—known by the slang term “potato masher”—exploded nearby.

The Rangers began scaling the cliffs. Lieutenant Moody led a group of Rangers to the top; they made it using bayonets and hand holds to assist each other. Once on top, they dropped toggle ropes to the others below. When Goranson reached the top he made an important battlefield decision: Instead of heading west to attack the Germans on Pointe de la Percée in support of the Rangers at Pointe du Hoc, he would attack east and clear the German positions wreaking havoc on the men of the 116th. It was the right call.

The second wave of the 1st Battalion, 116th Infantry, now headed to Dog Green. Some of the men spent the journey bailing water out of their landing craft with their helmets. As 12 landing craft carrying Companies B and D approached the beach, the soldiers saw only dead bodies in the water and on the sand. The ramps lowered, and the men, who had expected the battle to have moved inland, stumbled into a live battlefield. Much like Company A, many were hit as they exited their landing craft. Only three LCA captains had the wherewithal to change course, swinging to the east to land their Company B soldiers on Dog White Beach.

Most of the men landing on Dog Green waded ashore in waist-deep water. One Company B landing craft struck a mine and exploded, showering another craft with wood, metal, and body parts. Captain Ettore Zappacosta, the company commander, exited first from his craft and was shot while on the ramp. “I’m hit!” he called out before dropping beneath the waves.

German machine gunners then targeted the tightly packed men. Only one soldier from Zappacosta’s craft survived the onslaught. An explosion rocked another LCA. Someone yelled “Abandon ship!” and soldiers tossed themselves over the sides. Other LCAs’ ramps dropped and the men plunged into the surf amid a storm of machine-gun fire and geysers from mortar rounds.

Two soldiers, Lieutenant Leo Pingenot and Staff Sgt. Odell Padgett, made it ashore, climbing over boulders until they reached the base of the cliff on Charlie Beach. Looking back they saw the rest of their men in the water. “Are you hit?” Padgett shouted. The men answered back no, they were just seeking cover in the obstacles. With Pingenot and Padgett’s shouts of encouragement, the rest of the men made it to shore. Those who stayed behind the hedgehogs on the shoreline were easy targets for German mortars. The Company B survivors followed the Rangers up the cliff facing Charlie Beach.

The men in the water and on the beach fought back as best they could. After German machine-gun fire shattered part of Private Harold Baumgarten’s rifle, he balanced it on a hedgehog and fired at a German helmet in a machine-gun nest up on the bluff. The machine gun stopped firing, but as Baumgarten tried to eject the spent casing, the rifle broke in half. Seconds later, an enemy shell explosion drove shrapnel into his cheek, tearing out teeth and gums.

Sergeant Thomas Valence fired his rifle vainly at a concrete bunker. When a sergeant asked George Roach what he was shooting at, he told him, “I don’t know. I don’t know what I’m firing at.”

As Company D headed to the beach, one craft floundered in the surf. A German 88mm shell hit another LCA, blasting through its ramp and blowing out its interior doors. Only a handful of the Stonewallers from the craft made it to the seawall. Another landing craft dropped off its men too far from the shore, leaving them to swim to the beach. Other soldiers waded through the water, watching their landing craft attract fire.

When a medical LCA dropped its ramp, the Germans opened fire, killing almost everyone onboard. Their bodies drifted in with the tide. Soldiers in the water pushed the wounded ahead of them to get them to the shore. “All the Germans had to do to wipe us out was send a squad of armed men down the beach,” Private Baumgarten later wrote.

A single landing craft from Company D touched down 200 yards east of Vierville. Clusters of German artillery exploded on the beach and in the water as the ramp lowered. The craft rose and fell in the waves. As the first man jumped off mid-ramp, the craft dropped on top of him, killing him instantly. The rest pulled themselves over the sides. Sergeant John Slaughter washed up to the water’s edge and found himself under a mine-topped German obstacle. He watched the Germans gun down one of his comrades running across the beach, then the corpsman who ran out to help him.

Ordering the rest of his squad to follow, Slaughter charged off the beach, racing the 400 yards to the seawall. The survivors of the squad followed. Once under cover, they realized their weapons were jammed with salt water and sand. Slaughter took off his assault jacket, spread his raincoat on the sand, and began cleaning his M-1 rifle. When he saw bullet holes in his pack and coat, he became weak in the knees and his hands shook.

Also landing at the base of the cliffs where the Rangers had landed were three British LCAs, carrying Lt. Col. John Metcalfe and his 1st Battalion headquarters. Metcalf’s team took heavy casualties running from the surf to the cliff and found themselves pinned down by the intense enemy fire. For most of the day, Metcalfe could do practically nothing to lead his men, but when a soldier came by looking for a noncommissioned officer to take out a sniper, Metcalf volunteered to do it himself. A medic watched as Metcalfe went forward then followed after him.

Sometime around 7:20 am, less than an hour after the first wave landed, Dog Green Beach was closed. Three companies had already been decimated in less than an hour. Generals Gerow and Omar Bradley, the First Army commander, had deemed further assaults on Vierville Draw as suicidal. The beach and water were red with blood. Equipment littered the beach. Tanks burned furiously. Bodies floated in the water like driftwood, more like the results of a sinking ship than a battle.

Reinforcements Arrive

With Dog Green closed, the next 116th unit to land, Company C, was diverted east. Its landing craft touched down almost directly between the Les Moulins and Vierville Draws on Dog White Beach, just east of the Company B soldiers who had diverted from Dog Green. The company almost lost its commander when Captain Berthier Hawks rushed down the ramp and into water over his head, crushing his foot in the process. He climbed back on board as the boat moved closer.

Another LCA reached the shore and the men were ordered to go over the side. Most climbed over but three soldiers lay down in the craft and refused to leave. Another of the landing craft hit an obstacle that flipped it onto its side. Men spilled out and most of their heavy weapons—flamethrowers, Bangalore torpedoes, and demolition charges—fell into the water.

The Stonewallers heading into shore struggled to stay ahead of the incoming tide. Looking behind them, they saw floating dead bodies. Most of the men made it to the beach, where a soldier with a missing leg screamed for a medic. The men took cover in a number of breakwaters—rows of small wooden walls that jutted into the water, built to prevent beach erosion. These breakwaters protected them from flanking fire and gave them a chance to recover from seasickness and the ordeal of reaching the beach.

Next to touch down at approximately 7:50 am was Lt. Col. Max Schneider’s Ranger Force C of more than 600 soldiers. Having never received the reinforcement signal from Colonel Rudder on Pointe du Hoc, the Rangers headed for Omaha Beach. Schneider’s 5th Ranger Battalion and Companies A and B from 2nd Battalion approached beaches straddling both Dog Green and Dog White. The 2nd Battalion Rangers landed first and struggled through waist-deep water while their landing craft came under fire. One of the craft hit a mine and blew up. The fire was so intense that the Rangers who made it ashore retreated back into the water for protection and to let the high tide carry them in. “Dead men seemed to be everywhere,” said Company B Ranger Captain Edgar Arnold.

When Lt. Col. Schneider, still aboard his landing craft, saw the fire ripping apart the 2nd Battalion men, he told his British landing craft captain, “I’m not going to waste my battalion on that beach!” He decided to head farther east and landed on the heels of the Stonewallers’ Company C. Men ran up the shoreline, but only half reached the safety of the breakwaters, leaving the beach strewn with dead bodies.

Only one Ranger did not charge the beach. Father Joe Lacy, the Ranger’s 39-year old, overweight chaplain, remained at the water’s edge, pulling wounded forward, ahead of the rising tide. He treated their wounds and calmly prayed over the dead and dying, ignoring the enemy fire. Before his landing craft had reached the shore, he had warned the soldiers that if he saw any of them praying on the beach he would kick them in their rears. “You leave the praying to me and you do the fighting.” He kept his word—and then some.

Right behind the Rangers came two Landing Craft Infantry (LCIs): LCI-91 and LCI-92. LCIs were 160-foot-long craft capable of delivering 200 men via two foot ramps that dropped down from either side of the bow. LCI-91’s ramps dropped and soldiers from the backup headquarters for the 116th’s 1st Battalion headed into the surf until a teller mine on a pole exploded on the port bow. The ramps retracted and LCI-91 pulled away, returning 100 yards to the west to continue its job.

The ramps dropped again and the men exited. As the last of the men departed, an 88mm shell exploded the ship’s fuel tanks. Then enemy fire hit a soldier armed with a flamethrower and ignited his tanks, spreading fire all over the deck. He jumped overboard with even the soles of his shoes on fire.

The ship’s captain ordered everyone over the side. Men jumped in and found themselves in water over their heads. LCI-92 approached close to LCI-91 and suffered the same fate. LCI-92, carrying engineers from the 121st Engineer Combat Battalion, caught an 88 round in the midsection. The resulting explosion and fire tossed men overboard. Others, some of whom were on fire, jumped in.

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Ploger, the commander of the 121st ECG, almost drowned but inflated his life belt before the water overwhelmed him. Once ashore, Ploger ran 150 yards up the beach and had dropped into a shell hole when a German bullet hit him in the left ankle. He looked behind himself and could not see any members of his team.

Sergeant Deb Peters, who made it ashore by pulling himself along the telephone poles topped with mines, made it to the beach and hid behind a tank until an 88 round hit it, killing the men around him and embedding shrapnel in his cheek.

Six bulldozers loaded with boxes of dynamite made it ashore, two of which were immediately disabled by artillery. The engineers who had survived their fiery and watery ordeal found their efforts to destroy beach obstacles on the waterline blocked by infantrymen hiding behind them.

Despite the massive amounts of German fire, increasing numbers of Stonewallers and Rangers assembled on the beach and were ready to fight. Finally some leadership arrived as well. As Lt. Col. Schneider’s craft headed to the beach, an LVCP landed ahead of it. Aboard were Brig. Gen. Norman “Dutch” Cota, the 29th Infantry Division’s assistant commander, and Colonel Charles Canham, the 116th’s regimental commander, and their staffs. When they splashed their way up to the waterbreaks on Dog White, Cota knew he had to get the men moving and fighting.

Waving his pistol in the air, Cota shouted at the stunned soldiers to advance. When a lieutenant asked Cota what they should be doing, Cota told him, “Well, Lieutenant, we’ve got to get them off the beach. We’ve got to get them moving.” He then made his way to the men lying on the sand, tapping them on their rears and telling them, “Twenty-Nine, let’s go!”

When Cota found Lt. Col. Schneider, the two officers exchanged salutes and Cota gave Schnieder his marching orders: “Colonel, you are going to have to lead the way. We are bogged down. We’ve got to get these men off this goddamned beach!” Cota then turned to the Rangers and shouted, “Rangers! Lead the way!”

Meanwhile, Colonel Canham saw one of his C Company soldiers take a bullet to the chest while trying to cut through barbed wire. Canham crawled to the man, pulled the wire cutters out of his dead hand, and continued the job. As he finished, a German bullet tore though his wrist. A medic bandaged Canham’s wrist as he shouted out, “All of you who want to die, stay where you are, and those who want to live, come with me.”

To his officers and NCOs he said, “Get these men the hell off this goddamned beach and go kill some goddamn Krauts!” When a lieutenant colonel in a captured pillbox yelled for him to take cover, Canham shouted back, “Get your ass out of there and help me get these men the hell off this beach!” He then helped lead the men of Company C to the base of the cliff.

Back at the Vierville Draw

Meanwhile, atop the cliff on Charlie Beach, and west of the draw, Captain Goranson’s Company C Rangers, with the help of some Stonewallers from Company B, attacked a trench line connecting a pillbox, WN 73, and the fortified house, which had already been shattered by naval gunfire. The Americans surrounded the house and then advanced up the hill, wary of Germans lurking in the shadows. Soldiers tossed phosphorous grenades into dugouts and trenches between WN 73 and WN 72. Ranger Lieutenant Sidney Salomon reached the top of the ridge and captured an enemy soldier near an unmanned 80mm mortar position.

German soldiers in the damaged house fired on anyone passing by. Some Rangers returned the favor. Sergeant Belcher stuck his rifle over the edge of a trench only to be confronted by a German pointing a rifle at his head. Both men fired and both weapons jammed. The German ducked back into his position, but Belcher and another Ranger leaped into the trench and gunned down the German and two of his comrades.

The men then spotted a pillbox pouring fire onto the beach. Belcher kicked open the pillbox’s door and tossed in a phosphorous grenade. Flaming Germans soon poured out, screaming as the phosphorous burned their clothes and skin; Belcher and the other Rangers shot them down.

The Americans spent the rest of the day eradicating the Germans from the bluffs east of the draw. Goranson tried to contact elements of the 116th Regiment on his radio. He believed his Rangers were the only living troops on the beach until he finally reached someone in Company B.

Down on the beach, soldiers on the opposite side of the draw continued to fight. Some Company D soldiers and other survivors assembled a .30-caliber machine gun and fired it at the pillbox housing a German 88mm gun. Tracers ricocheted around the opening until the machine gun jammed and had to be moved.

The Dog White Assault

Back on Dog White Beach, Schneider’s Rangers, the Stonewallers of Company C, and the survivors of Company B began their assault. A soldier wielding a BAR crawled forward to where Colonel Canham had torn a partial hole through the wire. He placed a Bangalore torpedo through the rest of the wire and ignited it. The explosion cleared most of the way. The BAR man then dropped his body onto the remaining wire to form a human bridge and allowing the men to cross over.

Another Company C soldier, armed with a Bangalore torpedo, climbed through a gap in the seawall, jumped a strand of barbed wire, and was preparing to set the torpedo off under a second double-coil line of barbed wire when a German shot him down. A lieutenant reached the torpedo and lit the fuse. After the explosion, men rushed through the second gap and across the road paralleling the beach.

The men made their way to a grassy field that led to the base of the bluffs overlooking the beach. There they found a line of German trenches that enabled them to reach the bluffs without tripping any mines. Under the cover of smoke from the grass fires, Stonewallers climbed up the bluffs diagonally to the right in single file, checking for mines as they went. A machine gun in a pillbox halfway up the hill opened fire, impeding the advance––until a soldier with a flamethrower shot a stream of flame into its firing slits, incinerating the Germans inside.

Next to advance were Schneider’s 5th Rangers. They quickly blasted four lanes through the barbed wire and charged over the seawall, across the road, and to the bluffs. Like the other units, the Rangers ascended the bluffs diagonally to their right. Unfortunately, the smoke that had worked wonders covering the other forces, blew right into their faces, choking the men. Captain John Raaen put on his gas mask, only to find he had forgotten to remove the covering plug, almost suffocating himself. He finally fixed it and walked forward. After three steps he was out of the smoke, but he was so furious with himself that he kept the mask on for another 50 feet.

As more and more Rangers reached the top of the bluff, they came under crossfire from two enemy machine guns. General Cota showed up and declared “Now, let’s see what you are made of. This is how ya tell the men from the boys.” The Rangers headed down a ditch along a low hedge and flanked a German machine-gun emplacement. Not only did they bring it under fire, but one Ranger captured the German MG42 machine gun that had been firing on them. With this extra firepower, the men poured fire into the enemy trenches and at fleeing Germans.

Individually, the Rangers from Companies A and B, 2nd Rangers, made it to the road without having to wrestle with barbed wire—there was none in their path. They, too, ascended the bluffs. Ranger Sergeant William Courtney from Company A stood up on top of the ridge and shouted out, “Come on! The S.O.B.’s are cleaned out!” Just then an enemy machine gun opened up on him. He ducked, returned fire, and knocked out the gun nest. He stood up again, repeating his words. Other Rangers made it to the top and, in groups of twos and threes, knocked out strongpoints along the trench system and collected surrendering Germans.

As more and more troops followed up the bluff, a lost group from the 116th’s Company D arrived in a Landing Craft Mechanized (LCM). The men’s original LCA had been swamped and they transferred to the LCM, missing the follow-up assault. Now they joined the Rangers. Additionally, the 2nd Ranger’s B Company, which had landed before Schneider shifted the rest of his force to the east, also joined the fight.

Other small groups of men began to organize themselves and climb the seawall. One group of wounded men worked their way up the bluff near the draw and headed west toward Vierville until a German machine gunner firing from behind a low wall pinned them down. But when the German poked his head up, the wounded Private Baumgarten shot him dead. The group continued to skirmish with German soldiers, shooting any who surrendered.

Another group composed mostly of Company D men ascended the bluffs, following white tape they assumed had been placed by German work crews. Sergeant William Presley found a dead American naval officer with a radio strapped to his back and used it to call a destroyer, the USS Satterlee, to fire on a bunker housing a battery of Nebelwerfer rockets and 105mm mortars. The Navy salvos quickly destroyed it. In all, a force of some 600 Americans made it up the bluffs east of the draw.

South to Vierville and North to the Beach

Once past the bluffs, the soldiers of C Company reached a road that led them into Vierville around 10 am. They encountered no enemy resistance, only General Cota twirling a Colt .45 on his finger and chomping on his cigar. “Where the hell have you been, boys?” he asked.

As the men dug foxholes they came under fire. Fifteen soldiers were killed by unseen German snipers until a sergeant ordered, “Fire at those trees at the other end on the right!” The men opened fire and killed two Germans strapped to tree limbs. The town was captured, effectively flanking the draw, only 200 yards away.

Meanwhile, Colonel Schneider’s 5th Ranger force pushed farther south into the hedgerows, skirting Vierville as they focused on reaching Pointe du Hoc, four miles to the west. But the Rangers encountered fierce resistance. After fighting south for several hours, Schneider turned his men north to Vierville where, at around noon, they joined the Stonewallers. The combined force could not break through the Germans to their south and west. Already the hedgerow country was proving too difficult for infantrymen to maneuver.

General Cota approached the Rangers, asking them why they were being delayed. “Snipers,” one of them said. “Snipers?” retorted Cota. “There aren’t any snipers here!” A shot rang out, passing close to the general. “Well, maybe there are,” he said and walked off.

Colonel Canham showed up and ordered the Rangers to abandon their Pointe du Hoc mission and to spread out in the hedgerows and defend the ground taken. To Canham, it was more important to prevent the Germans from recapturing the Vierville Draw than risk a solid force of Rangers on a questionable mission.

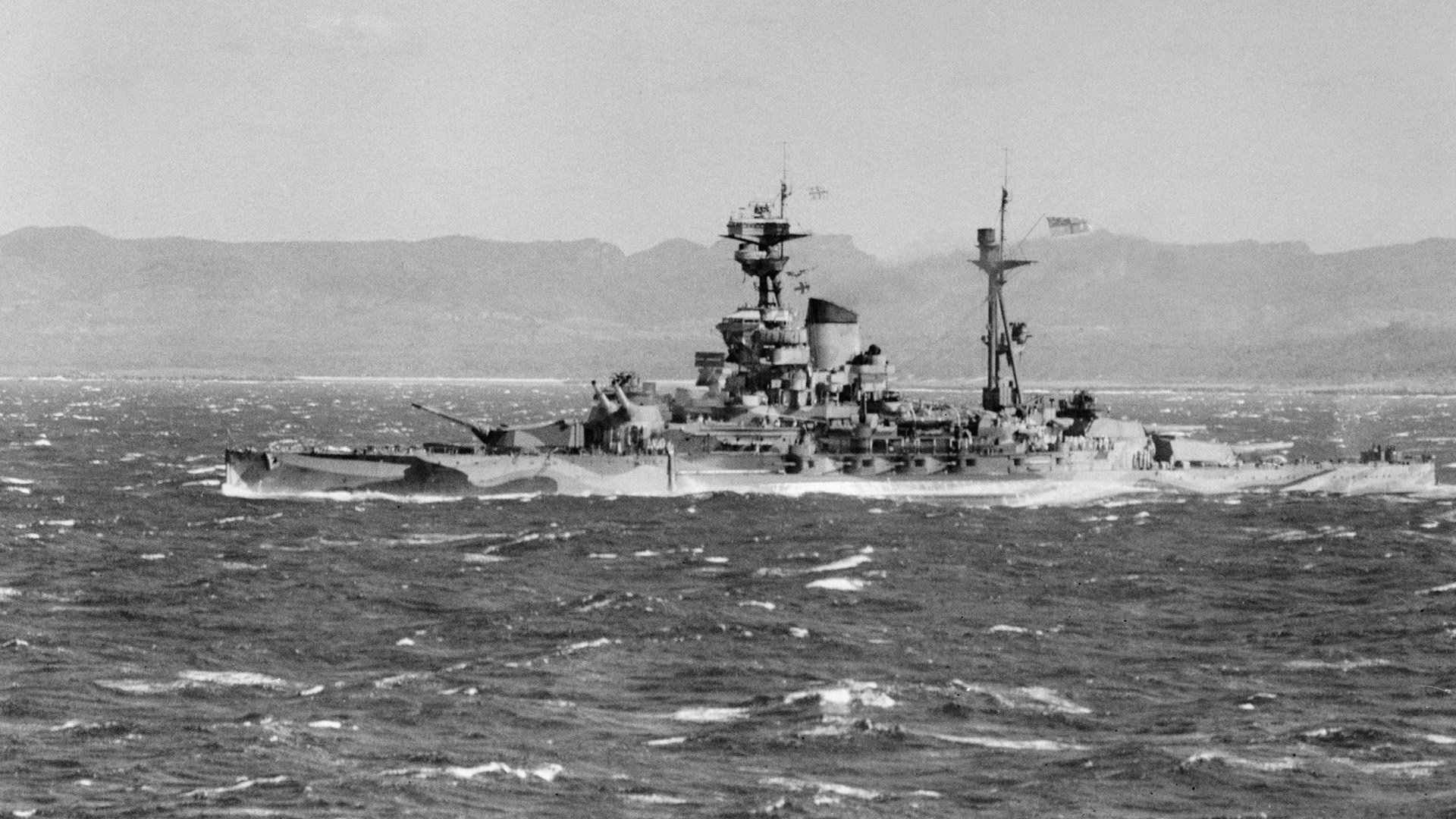

Out at sea, the destroyers USS McCook, USS Harding and USS Satterlee and the battleship USS Texas fired continuously at the Vierville Draw’s defenses. With the assistance of Navy shore fire control parties and signal men aboard landing craft close to the action, their salvos destroyed a number of bunkers disguised as houses. The Texas had opened the morning assault, firing over the DD tanks as they headed to shore. The Harding fired 40 shells at the steeple of the Vierville church, completely destroying it. The Satterlee, which had spent the morning firing on Pointe du Hoc, knocked out the Nebelwerfer, as requested by Sergeant Presley. Twenty minutes after noon the McCook fired on the cliff at Charlie Beach, knocking a large artillery piece off the cliff ledge. Unfortunately, it also caused a rock slide, killing wounded men lying below.

Some of those men were from 1st Battalion headquarters. Major Thomas Dallas, the battalion’s executive officer, fired orange smoke to mark their position. The Navy misinterpreted the signal and fired on the party. “Goddamn it,” Dallas yelled at his signal officers, “tell those sons-of-bitches to stop the firing!” Two signalmen fashioned semaphore flags from sticks and handkerchiefs and signaled the ship to stop firing; the crew of the McCook had mistaken them for surrendering Germans. Dallas later reported that more men were killed by naval fire than enemy fire.

While the McCook rained fire on the Vierville bluff, General Cota led his small force north to the draw where his men quickly captured a number of Germans who came out of their bunkers with their hands up or waving white flags. The naval bombardment had done its job. Cota’s team led their prisoners down toward the beach, until the general spotted two Germans on top of WN 71. “Come on down here, you sons-of-bitches,” he called while waving his pistol at them. They followed suit.

Cota then pointed to WN 71 on the cliff, telling his aide-de-camp to keep a sharp eye out for the enemy. Sure enough, Germans stationed inside the cliff soon opened fire, but American return fire drove five of them from their positions. Later, an additional 54 prisoners were taken from the cave inside the cliff.

Cota’s group reached the pillbox on the east side of the draw (the one with the 88), but as they passed through an opening in the two antitank walls the Germans prisoners became frantic, yelling, “Minen! Minen!” out of fear of German-laid minefields. Cota dismissed their cries and ordered them forward with a sweep of his hand. The wary men obeyed and the Americans and their prisoners walked back down to the beach. The Americans now held the Vierville Draw but the double wall between the pillbox and the cliff still blocked the way for vehicles. It had to be destroyed.

Cota found Colonel Lucius Chase of the 6th Engineer Special Brigade, who offered numerous excuses why he couldn’t destroy the walls. Cota pointed to a bulldozer with 20 cases of TNT strapped to it and told him to use it. Continuing down the beach, Cota came across another bulldozer loaded with TNT and asked one of the huddled soldiers behind the seawall to drive it over to the draw. Other scattered engineers converged on the draw and prepared the wall for demolition.

First, the engineers posted men on either side of the walls to make sure no Americans would be near the explosion. Then they snaked Bangalore torpedoes through the protective barbed wire and detonated them. The walls were ready for destruction, but the engineers worried that they might be reinforced with steel rods, requiring more explosives than they possessed.

With no other options, the engineers built a short wooden platform for the TNT so the detonation would not destroy the road beneath. They laid four boxes of TNT along the bottom of the first wall, then stacked three more boxes on top of the end boxes, forming a U-shaped charge. They then opened one box, attached a blasting cap to a block of TNT, and pulled the igniter. The men rushed to safety behind the seawall. There was a huge blast.

When the rain of concrete rubble ceased and the smoke cleared, the men were surprised to discover that both walls had been destroyed. There had been no steel reinforcement. A bulldozer roared forward and cleared the debris off the road. It was 4 pm––just 91/2 hours after the first wave landed.

The road inland was now open. Tanks, trucks, jeeps, and other vehicles could safely roll off landing craft, cross the beach, and head up the road into the villages and towns beyond. The most important objective on Omaha Beach was now in American hands. It had been a deadly effort, but the Americans of the 116th Regiment, the Rangers, and their support units gained the initiative and drove the Germans from the vital draw.

of all the many descriptions I’ve read about fighting on bloody Omaha,

this is the most powerful.

I visited Omaha Beach in 1962. I stood on top of one of the pillboxes which looked down on the beach area. Even then I wondered how our boys ever made it across that beach and up that hill while enduring the firepower of the German army. I spent 2 years in Paris working with the Church of Christ.

That bunker at WN72 did not house a “50-caliber machine gun”. Germans did not have 50-caliber machine guns. That bunker housed a 5cm Kwk 38 I/42 on a swivel.

I’m fairly certain that the unnamed BAR man in the paragraph “The Dog White Assault” was my father. When he was disabled by a stroke in 1990. He remained under VA care in North Little Rock AR (Towbin

VA Med Ctr) until his death in 2004. He had not shared any of his war experiences until becoming a resident at Towbin. He was cited on the battlefield for the Bronze Star but did not receive it until a chaplain at Towbin arranged a ceremony in January 1996(?) one year after my mother had passed away. He was also responsible for taking out a sniper hidden in the chimney of a destroyed building after receiving an order (probably from.Canaham) “Cut ‘I’m down, Arkie!” as they entered Vierville. Dad said he used his BAR every day until being wounded while trying to get closer to an MG 42 nest on the approach to St.Lo on July 3rd. Average life expectancy for a BAR man after firing in an engagement was something like 7 seconds. That was longer than a radio man but still miraculous that he survived and fathered me and my 3 siblings to adulthood.