By Arnold Blumberg

After the crushing Union defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln relieved Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside from command of the Army of the Potomac. However, impressed with his assumption of full responsibility for the failure at Fredericksburg, Lincoln assigned the humiliated officer to head the Department of the Ohio encompassing the states of Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and most of Kentucky.

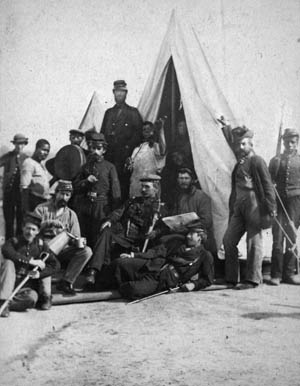

Taking up his new duties in mid-March 1863, Burnside spent the next several months securing Kentucky from guerrilla forces, cracking down on seditious civilians residing north of the Ohio River, and creating a field force for the long-awaited invasion of East Tennessee, an operation his superiors in Washington had urged him to undertake. Burnside’s field force, totaling 31,000 men, was organized into two corps: three infantry divisions comprising his old command, the IX Infantry Corps, plus two divisions of the XXIII Corps and a cavalry corps of two divisions.

At the end of May, Burnside prepared to cross his army over the Cumberland River into East Tennessee to guard the left flank of Union Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland as it marched through the Volunteer State to the critical Confederate railroad center at Chattanooga. However, before Burnside could advance, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, general-in-chief of the Union armies, directed him to send 8,000 of his men to Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, then besieging Vicksburg, Mississippi. Burnside dutifully sent two divisions (8,600 soldiers) of the IX Corps. With most of his veteran IX Corps gone, Burnside was hard pressed to find enough troops to defend Kentucky, let alone mount a serious incursion into East Tennessee.

In late July, Halleck’s badgering of Burnside to mount a full Union invasion reached a crescendo, even though IX Corps was still with Grant on the Mississippi River, and Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan’s Confederate cavalry was boldly raiding through Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio. Burnside responded that he could scrape together 12,000 men for the enterprise, but that it would weaken the defense of the Bluegrass State and make his lines of communication into East Tennessee vulnerable. Halleck, unmoved by his subordinate’s plight, ordered an immediate move on Knoxville.

Burnside’s March to the Tennessee River

On August 16, Burnside’s command, principally XXIII Corps (IX Corps, only 6,000 strong, would not join him until October), in five columns spread over a 100-mile distance, began its march to the Tennessee River on atrocious, bottomless mountain roads without sufficient transport to carry food or forage through a picked-over landscape destitute of resources. The Federal forces went on half rations immediately after commencing their march. The columns melded into one as they neared the Tennessee River at Kingston on September 2, 40 miles to the east. The day before, Federal cavalry had occupied Knoxville without a fight. Burnside pushed some of his mounted men 50 miles south of the Tennessee to connect with Rosecrans’s left as it swept toward Chattanooga. Meanwhile, Southern forces of the Confederate Department of East Tennessee, outnumbered and spread thin, retreated 100 miles southwest of Knoxville. Another 2,000 Confederates garrisoning Cumberland Gap, 60 miles north of the city, were captured by Burnside’s invaders on September 9 with scarcely a shot being fired.

Burnside intended to use Knoxville as a fortified camp from which Union forces would control East Tennessee, but his resolve was soon shaken by reports that reinforcements from Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had boarded trains in the Old Dominion and were heading his way. It was true. Elements of Lee’s army were heading south, but East Tennessee was not their intended destination. Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s formidable I Corps (two infantry divisions and one artillery battalion) had been dispatched to the western theater in response to the imminent loss of Chattanooga by General Braxton Bragg and his luckless Army of Tennessee. The city fell to the Federals on September 9. Its capture meant that the door to the interior of the Confederacy was thrown open, presaging an enemy invasion of the Confederate heartland. To forestall such a strategic catastrophe, the Richmond government had sent Longstreet and two-thirds of his corps from Bristol, Virginia, on an 800-mile roundabout journey via Georgia to Bragg’s assistance. The first trains carrying Longstreet’s veterans rolled toward Chattanooga the same day the city fell.

Burnside’s assumption that Lee’s reinforcements were meant to eject him from East Tennessee was a reasonable one. Longstreet had been sent to join Bragg in northern Georgia due to the mistaken belief that Rosecrans and Burnside intended to combine against Bragg. Had he known that Burnside was moving on Knoxville instead, Lee wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, he would have sent Longstreet there instead to contest the Federal occupation of East Tennessee and protect the integrity of the Confederacy’s east-west communications. The move against Burnside made other military sense as well since his was the smaller army, his flank was in the air, and his supply line to Kentucky was very precarious.

As Burnside pondered whether he could defend his area of responsibility (nearly 200 miles of front, and 200 miles from his supply base in Kentucky) with only 20,000 men, he began to receive a string of disconcerting messages from Halleck, who directed him to forward to Rosecrans as many men he could spare as soon as possible since Bragg was about to attack at any moment. Burnside sent two infantry divisions and some cavalry, about half his combat strength, south of the Tennessee River to join Rosecrans. However, these troops were blocked by Southern forces and ultimately returned to Burnside.

Holding the Knoxville Area

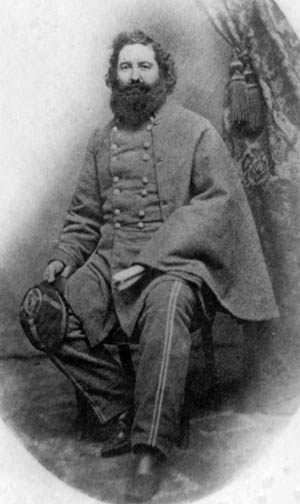

After Longstreet had spearheaded the Confederate victory at the Battle of Chickamauga on September 19-20, a growing rift between him and Bragg prompted Jefferson Davis to propose that Longstreet be sent north to oust the Union forces occupying East Tennessee. Bragg readily agreed. Longstreet strongly disagreed, warning, “We thus expose both to failure, and really take no chance to ourselves of great result.” Later he would say, “It was the fate of our army to wait until all good opportunities had passed, and then, in desperation, seize upon the least favorable movement.” Nevertheless, Longstreet began implementing the scheme on November 4 when the first 12,000 men and two artillery battalions (35 guns), supported by 5,000 horse soldiers under Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, left the vicinity of Chattanooga. On November 13, after moving by rail and road, Longstreet’s force appeared just south of the Tennessee River near the town of Loudon.

Longstreet initially planned to approach Knoxville from the south, but without enough wagons to carry the pontoons he needed to cross the rivers and creeks along the way, he had to move his bridging equipment by rail as close to the Tennessee as possible. This forced him to cross to the north bank of the waterway miles west of Knoxville, then strike east toward the city. Once across, he wanted to bring his enemy to battle as soon as possible. An early fight was essential to conserve his troop strength and dwindling supplies and deny Burnside the opportunity to be reinforced.

Meanwhile, Burnside was informed that his new immediate superior, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who had replaced the ill-starred Rosecrans, intended to attack Bragg near Chattanooga, thus forcing Longstreet to return to the Army of Tennessee. In Grant’s opinion, Burnside must control the Knoxville area as long as possible while Bragg was disposed of. Grant would then send a relief force to Burnside within a week of defeating Bragg. Burnside agreed; he would delay Longstreet’s advance on Knoxville then hold the city as long as he could.

The Battle of Campbell’s Station

On November 14, the Confederates lurched over the Tennessee under a rainy sky, with Brig. Gen. Micah Jenkins’s infantry division leading the way at Hough’s Ferry just short of Loudon and 40 miles west of Knoxville. As Jenkins crossed, Longstreet’s other division, under Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, diverted enemy attention from the real crossing site with a move to the northeast. A further diversion was undertaken by Wheeler’s cavalry to threaten Knoxville from the south side of the river.

While Longstreet’s advance guard spilled over the Tennessee, Burnside concentrated his nearest combat units, Brig. Gen. Julius White’s 2nd Division, XXIII Corps, near the ferry, and Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero’s 1st Division, IX Corps, at Lenoir’s Station on the Tennessee & Georgia Railroad, and sent them to confront the enemy spearhead. After shaking out a thin battle line, White and Ferrero drove the Confederate skirmishers for a mile and a half until the arrival of Southern reinforcements, darkness and pelting rain halted the Union advance. Burnside ordered a night attack but cancelled it. Instead, he decided to give up the fight at the river in order to lure Longstreet toward Knoxville, farther away from Bragg, while Grant struck the Confederate army at Chattanooga.

At dawn on the 15th, the Federal columns commenced their retreat to Lenoir’s Station, and by dusk had formed a strong defensive shield north and northeast of that place to cover the next Union retrograde movement toward Knoxville. As Burnside put more men, guns, and wagons in motion from Lenoir’s on the road to Knoxville that night, Jenkins’s division, with McLaws to its north, approached Lenoir’s. Throughout the early-morning hours of the 16th, Burnside pulled out of Lenoir’s Station and headed for Campbell’s Station, 10 miles farther up the rail line. Soon Jenkins and McLaws were hard on the Federals’ trail.

Throughout the cold November day, the Confederates came up against a succession of enemy blocking positions at Little Turkey Creek, Smith’s Hill, Road Junction, Turkey Creek, and Loveville. These actions, ranging from intensive skirmishing to prolonged artillery duels, coupled with unsuccessful Confederate flanking movements, lasted until 6 pm. The series of fights on the 16th, collectively referred to as the Battle of Campbell’s Station, cost the Union 318 men killed, wounded, and missing. Jenkins lost 174 men from all causes; McLaws never reported his loss tally. As dark settled over the area, Burnside continued his retreat to Knoxville under drizzly skies and over ankle-deep muddy roads. By 4 am on the 17th, the first of White’s and Potter’s 5,000 men straggled into the city. Longstreet’s force did not follow, but bivouacked on the field at Loveville that night.

General Sander’s Stand

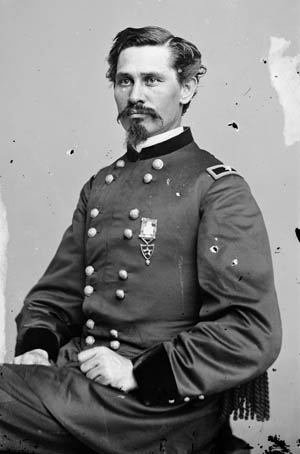

Bestirring themselves on the morning of November 17, the foot soldiers of McLaws’ division led the chase toward Knoxville. Four miles west of the town they collided with four regiments belonging to Brig. Gen. William P. Sanders’s 1st Cavalry Division. Sanders and his troopers had for the past several days blocked the path of Wheeler’s cavalry trying to reach Knoxville from the south over the Tennessee River. After frustrating Wheeler, they traveled west to help delay Longstreet’s main force. During the day the blue riders took up three successive positions along the Kingston Road just outside Knoxville, delaying the Confederate infantry while Burnside got his men to work creating a defensible line to protect the city.

Posting 600 men behind three-foot-high rail breastworks, in a line stretching from the Tennessee River to the wooded valley of Third Creek, and resting his right on a bare hill a little farther to the north, only two miles west of Knoxville, Sanders was able to foil repeated attacks made by clouds of Confederate skirmishers from 10 am to 1 pm on November 18. As Colonel E. Porter Alexander, Longstreet’s chief of artillery, stated afterward, “Here these fellows held, and just would not quit for anything our skirmishers could do to them.” Sanders, suicidally exposing himself, walked the fence line rallying his men.

Finally, Longstreet ordered a full-scale attack on Sanders’s position, preceded by a preliminary artillery bombardment followed by an assault delivered by Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw’s infantry brigade of McLaws’ division. The Confederates went in at 3 pm and drove the Federal cavalrymen from their works, mortally wounding their commander. “I told Sanders not to expose himself,” a grief-stricken Burnside said, “but he would do it.” Union losses in all totaled nearly 300 men; the Confederates lost 140.

As heroic as Sanders’s delaying action was on the 18th, it was unnecessary. Longstreet had determined earlier that day that he could not attack the growing Union defenses—slim as they were—with any chance of success. Sanders had only blocked the enemy along the Kingston Road. Jenkins’s force, north of the Kingston highway, had an unobstructed march to the main Union line protecting Knoxville on the 18th, but instead of attacking spent the entire day skirmishing with the Federals manning that part of the city’s defensive line.

The Defenses of Knoxville

On November 19, Longstreet closed in on Knoxville’s protective perimeter. For days thereafter he simply observed the Union positions. Lacking sufficient manpower or tools to completely encircle the city, he could not starve it into submission. The Confederates were themselves chronically short of supplies. Longstreet demurred when it came to a direct assault on Knoxville. His army was small (about 14,000 men and 35 cannons), and the chances of success in such an endeavor were uncertain against a fortified opponent 12,000 men strong with 51 pieces of artillery. Each day the Confederate general pondered how to take the city.

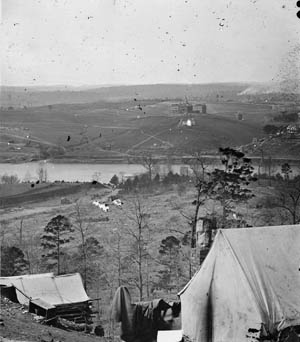

Knoxville, the prize that would once again assure Confederate control of East Tennessee, was the largest city in the predominantly pro-Union area. Most of the town was perched atop a half-mile-wide plateau between two creeks, standing 150 feet above the Tennessee River. The railroad to the north squared off the city’s boundary. East Knoxville, across First Creek, occupied two hills. Flint Hill rose near the river and the railway; 80 feet higher was Temperance Hill. Farther east and higher than the others was Mabry’s Hill on the Dandridge Road. West of town, the University of Tennessee sat on another plateau beyond Second Creek. A mile down river flowed Third Creek, which ran to the Tennessee.

Knoxville’s defenses had been in preparation since September of that year, and had been in the charge of Burnside’s chief engineer, Captain Orlando M. Poe. By mid-November, Poe had constructed 13 redoubts and batteries made of thick, wide parapets located on advantageous ground along the 100-foot-high ridge that started two miles northeast of town and paralleled the Tennessee River. Three more forts were constructed south of the river.

At the extreme northwest corner of the city’s defense system stood a star fort originally built by the Confederates and called Fort Loudon. Anchoring the entire Union defensive line, this bastion, the strongest work in the Federal defense scheme, was renamed Fort Sanders by the Federals after the fallen cavalry leader. It had an eight-foot-wide, six-foot-deep ditch around it, with a surrounding parapet 12 feet high. The irregular-quadrilateral star configuration was 95 yards on the west side, 125 yards on the north and south sides, and 85 yards on the east face. Two strongpoints on the northwest and southwest corners were built, with a single Napoleon smoothbore cannon sited in the northwest one. Because the ground in front of the northwest bastion sloped sharply in front of the position, the gun could not fully protect the site, and that sector of the fort remained a weak one. Unfortunately for the Federals occupying it, the fortification formed a salient that diffused the defenders’ fire. Situated as far down the hill crest as possible, its location also prevented the Federals from covering adequately all the ground along the line of approach.

In an attempt to remedy these shortcomings, Poe creatively used the remains of a forest fronting Fort Sanders. The woods had been cut down to tree stumps, and Poe strung reels of telegraph wire around the stumps, creating an entanglement both treacherous and almost invisible. In addition, an abatis was erected at a point between the northwest corner and a row of rifle pits 80 yards from the fort. The work’s parapets were reinforced with large bales of cotton covered with animal hides

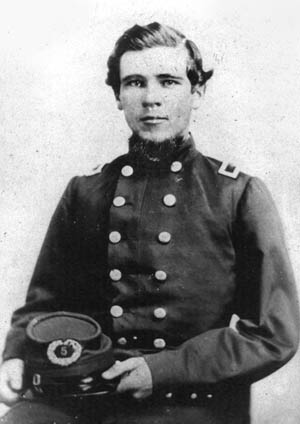

The Federal garrison of Fort Sanders comprised about 335 infantry picked from the 79th New York, 29th Massachusetts, 2nd Michigan, and 20th Michigan Infantry Regiments. The foot soldiers were supported three companies of artillery commanded by Lieutenant Samuel N. Benjamin, Captain William W. Buckley, and Captain Jacob Roemar, totaling 12 guns and 105 artillerymen. Benjamin, chief of artillery for IX Corps, was the de facto commander of the garrison. Stationed immediately to either side of the fort were an additional 500 men who could respond quickly to an attack on the post. Farther to the rear stood about 2,000 infantry in Colonels Benjamin C. Christ’s and William Humphreys’ brigades. Even with all the force concentrated at Fort Sanders, Poe admitted that the salient “caused us great anxiety.”

As the days dragged on, numerous petty skirmishes and sorties flared before the Federal main defensive line. Confederate sniper fire was especially galling, but sniper fire alone was not going to crack the Union lines. Alexander favored an attack on Fort Sanders, and from the early stages of the siege he concentrated his artillery fire against that post to weaken it preparatory to a ground assault. Longstreet was not so sure. He favored sending some of his men to the south side of the Tennessee and threatening Knoxville from the south, but all his preliminary attacks on this front ended in failure.

Longstreet Plans His Attack

Finally, on November 27, Longstreet determined to break the impasse at Knoxville with a full-blown assault on the Union entrenchments. The arrival of two infantry brigades (2,600 men) from Bragg’s army as reinforcements spurred him to that decision. Longstreet’s original target was Mabry’s Hill, with a diversionary advance on Fort Sanders. But later that day, standing 400 yards from Fort Sanders, Longstreet observed a Union soldier from the fort walking along the position’s protective ditch. It appeared to be only waist high and therefore not an obstacle to an attack. Longstreet did not realize that the enemy soldier had traversed the deep ditch on planks that been placed across it.

The attack, set for the 28th, was postponed until the 29th due to rain. McLaws’ men, stationed closest to Fort Sanders, were assigned the lead role. McLaws planned to maneuver a heavy skirmish line of 3,000 men to within 200 yards of the fort’s northwest bastion during the night. The Confederate skirmishers, it was hoped, would suppress the fire from the enemy entrenchments that would normally be directed at the assaulting force, as well as drive the enemy advance picket line back to within 80 yards of the fort’s northwest corner.

The main assault contingent was made up of two columns. On the right were Brig. Gen. Goode Bryan’s and Humphreys’ Georgia and Mississippi brigades, some 1,350 men. To the left was Brig. Gen. William Wofford’s Georgia brigade, under Colonel Solon Z. Ruff (1,080 soldiers). Behind the initial attacking formations, Jenkins’s three-brigade division (2,625 men) was ready to support McLaws’ left column, as was Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson’s newly arrived two-brigade division. They would widen the penetration of the Federal line if the fort was taken by the first assault troops. McLaws made no provision to fill in the ditch fronting the enemy position with fascines or employ scaling ladders since he, like Longstreet, wrongly assumed that the trench around Sanders was shallow.

Assault on Fort Sanders

The gray skirmish line started its advance at 10 am on the 28th, quickly gaining ground that brought them to within 80 to 120 yards of their objective. However, the Federals now knew an attack on Sanders was in the offing the next morning. They strengthened their lines in anticipation of such an attack. Unofficial reports of Bragg’s defeat at Chattanooga and his subsequent retreat to northern Georgia reached the Confederate camp that night, and McLaws recommended postponing the attack on Fort Sanders until they could better ascertain the situation. Longstreet refused. “It is a great mistake to suppose that there is any safety for us in going to Virginia if General Bragg has been defeated,” he said, “for we leave him at the mercy of his victors, and with his army destroyed our own had better be also, for we will not only be destroyed but disgraced. There is neither safety nor honor in any other course than the one I have chosen.” The attack would proceed.

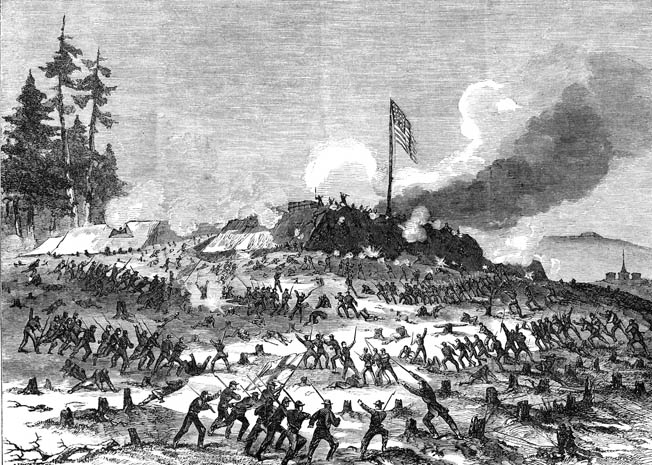

At 6 am on an intensely cold and foggy November 29, 20 Confederate artillery pieces opened fire on Fort Sanders as 6,000 of their infantry comrades waited to advance against the fort. The cannons in Fort Sanders did not at first reply, the Union gunners wishing to reserve their fire for the expected enemy infantry attack. At 6:20 am, the Confederate storming columns moved to the attack in utter silence. The first 150 yards of their trek was through tangled brush, but after that they reached open ground, reformed their ranks, and moved on. In the dim light many Confederates fell blindly over the wire obstacles and then encountered the abatis fronting the fort, causing confusion and hesitation in the columns. As the head of the gray assault force came within 50 yards of Fort Sanders’ northwest corner, the Union defenders opened fire, bringing down an estimated 60 Confederates.

As McLaws’ two rows of soldiers neared the fort, all command and control evaporated as more than 2,000 men rushed headlong toward the same target. At the same time, the mass of men came to an abrupt halt as it came to the deep, wide ditch fronting the northwest bastion of Fort Sanders. The attackers were surprised by its height—more than 18 feet—with an angled slope of 70 percent coated with a hard, slippery surface of icy mud. Orlando Poe, watching the Confederate assault, was moved to grudging admiration. “Although suffering from the terribly destructive fire to which they were subjected, they soon reached the outer brink of the ditch,” he reported. “There could be no pause at that point, and, leaping into the ditch in such numbers as nearly to fill it, they endeavored to scale the walls.”

Faced with the unexpected impediment, many Confederates jumped into ditch to avoid enemy fire, or were pushed by the pressure of those behind them. Others took shelter outside the ditch and fired at the Union parapet. The defenders, in their turn, blazed away at the enemy with rifle-muskets and double and triple canister rounds. Despite the desperate Union fire, some Confederates managed to surge into the fort twice within six minutes. The first attempt was easily repulsed, but the second saw the Southerners enter through the gun embrasures, plant three Confederate flags upon the parapet, and nearly overwhelm the Union garrison before the gray surge was pushed back. The cruel fact for the Confederates was that too few of them could climb out of the ditch and over the parapet at any one time to decisively tilt the balance of force in the Confederates’ favor. All who did so were either killed outright or quickly captured.

The fight degenerated into a bloody stalemate, with more and more Federal reserves pouring into Fort Sanders, doubling its original strength. Among those engaged was Lieutenant Sam Benjamin. He fought close up with his pistol and then started throwing lighted artillery shells into the mass of enemy soldiers struggling in the ditch. Benjamin’s improvised hand grenades, as well as flanking fire by the 20th Michigan Infantry Regiment hitting the Confederates in the ditch from the east, broke Confederate morale. Many in the ditch tried to flee or surrender.

The ditch had become a veritable death trap, reminiscent of a scene in Dante’s Inferno. “There was no need to take carefully aim,” recorded William Todd of the 79th New York. “The brave rebels crowded up to the ditch and almost every bullet fired by us found a death mark. Many tried to scramble out by making a platform of the bodies of their dead comrades, but few came out alive, and those only to be a mark for our unerring rifles. To most of those who entered, it was indeed the ‘Last Ditch.’”

It did not help the Confederate cause that Jenkins’s men failed to adequately support McLaws. Had they done their job, the murderous fire coming from the 20th Michigan would not have been directed at the Confederates trying to gain entrance in to the northwest strongpoint of Fort Sanders. Other units of Jenkins’s command also failed to attempt to break the Federal lines east of the fort as they were originally ordered to do. Johnson’s troops, which started the fight between 800 and 1,000 yards from Fort Sanders, pushed to within 250 yards of the Federal position but fell back to the main Confederate line when they saw McLaws’ attack apparently fail.

A 40 Minute Battle

Longstreet was near Johnson’s command when he noticed a flood of men making their way back from Fort Sanders. Informed by a staff officer that the attack could not succeed due to the wire entanglements and intense enemy fire, he brushed off Johnson’s plea to allow his men to carry on the offensive and instead ordered a general retreat. McLaws, consulting with his subordinate combat leaders, authorized his division to fall back 400 yards from Fort Sanders, then to the Confederate starting line. It was 6:45 am. The entire attack on Fort Sanders had lasted 40 minutes, half of that time being the struggle for control of the fort’s parapet.

After the battle was over, an eight-hour truce was made between the parties to recover the dead and wounded. The Federals collected 250 prisoners. In addition to the captured, the Confederates left behind 129 killed, 458 wounded, and 226 missing. In exchange for their gruesome losses, Longstreet’s men inflicted only 50 Union casualties, 20 of which occurred inside Fort Sanders.

Longstreet shouldered the blame for calling off the attack, but he severely criticized McLaws for the way the attack was carried out in the first place, blaming him for not having fascines and scaling ladders on hand. Longstreet’s reason was without foundation since every Confederate leader involved in planning the battle, including Longstreet himself, had assumed that such items were not needed since the ditch appeared to be no real hindrance. On the other side of the hill, Burnside lavished equal praise on Poe and Benjamin. To the rank and file defenders of Fort Sanders, the victory was sweet revenge, a virtual Battle of Fredericksburg in reverse.

Advised officially of Bragg’s crushing defeat at Lookout Mountain, Longstreeet at first was going to retreat from Knoxville but soon changed his mind. He reasoned that by holding on at Knoxville he would force Grant to send a force to relieve Burnside, thus taking some pressure off Bragg’s beaten army. In this, he was correct. Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman marched to Knoxville with 30,000 men, reaching the city on December 6. Longstreet had retreated the night before. He and his reduced army remained in East Tennessee throughout the winter and early spring, making occasional feints toward Knoxville, until Davis ordered him back to Virginia on April 17. Five days later Longstreet and his men were back in the Old Dominion and reunited with the Army of Northern Virginia, the bitter memories of the unfortunate East Tennessee operation behind them.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments