By David H. Lippman

In the high summer of 1944, the United States was coiling a massive fist in the Central Pacific aimed directly at the Mariana Islands, specifically Saipan, Tinian, and Guam. By taking these islands in the Marianas, the Americans could turn them into airbases for their Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers, which could in turn pound Japan’s factories and cities into rubble.

Saipan was the major target.To seize this island chain from the Japanese, the Americans assigned the U.S. Fifth Fleet, under Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, centered around 15 aircraft carriers and 10 fast battleships, 535 combatant ships and auxiliaries in all. The assault force would consist of 130,000 Marines and Army troops organized into the 3rd Amphibious Corps and the 5th Amphibious Corps. The latter formation, under Lt. Gen. Holland M. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith, was tasked with invading Saipan. It consisted of the 2nd Marine Division and the 4th Marine Division. Its floating reserve was the Army’s 27th Infantry Division, drawn from the New York State National Guard.

Operation Forager, as the descent on the Marianas was called, was a massive assault: Saipan was 3,500 miles from Pearl Harbor, and troops were embarked from Hawaii and the West Coast. A seaborne logistical framework of enormous proportions would be needed to keep the invading ships and men supplied with shells, bullets, and food. D-day was set for June 15.

The 43,682 Defenders of Saipan

The defense of Saipan was headed by the newly organized 31st Army, under Lt. Gen. Hideyoshi Obata, which was also responsible for the Caroline and Palau Islands. To hold these islands, Tokyo began pulling troops from the Manchurian border with the Soviet Union. Among the young men in the Japanese 118th Regiment was Sergeant Takeo Yamauchi, a conscripted Russian-language student, who admired Soviet communism. “We were laid out on shelves like broiler chickens. You had your pack, rifle, all your equipment with you,” he said later.

Obata now had an army of 22,702 men on Saipan, but it was an incredibly disorganized force. The naval forces were commanded by Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, commander of the attack on Pearl Harbor and the disaster for the Imperial Japanese Navy at Midway in June 1942. Nagumo had been assigned to command Saipan’s 6,690 officers and sailors, which included 800 men of the 1st Special Naval Landing Force, Japan’s version of America’s Marines, and 400 men of the 55th Naval Guard Force.

It all added up to 43,682 Japanese defenders on the rocky, craggy island, but Obata was not one of them. When the Americans arrived, their invasion caught him returning from an inspection trip to the Palaus, and he got no farther than Guam. The land battle would be conducted by Lt. Gen. Yoshitsugu Saito, centered on his own 43rd Infantry Division. His other forces included the 47th Independent Mixed Brigade, the 7th and 16th Independent Engineer Regiments, the 3rd Independent Mountain Artillery Regiment and its two dozen 75mm guns, the 25th Antiaircraft Regiment, and the surviving 36 medium T-97 and 12 light tanks of the 9th Tank Regiment.

Saito’s plan was simple: defeat the enemy on the beaches. To do so, Saito planned immediate counterattacks to weaken the Americans. Saito’s tanks would then deliver the knockout punch. Problem was, he did not know where the Americans would land, so he had to defend the entire coastline.

A Methodical Invasion Plan

The Americans, schooled in Japanese tenacity by bloody battles in the Solomons, New Guinea, and Tarawa, approached the invasion of Saipan with the thoroughness and technical skill that would be their hallmark throughout the Pacific campaigns. Both the Marines and the Army relied on solid combinations of artillery, armor, and infantry in battle, with the Army’s well-proven tactic of “holding attacks” to draw off the main defenders while a second force sought an opening on the flanks to defeat the enemy.

Operation Forager got down to business on June 11, when Spruance’s vast fleet steamed to within 200 miles of the Marianas and the carriers began turning into the wind to launch 200 Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters to hammer the 14 Japanese airfields on the islands. A heavy naval bombardment followed.

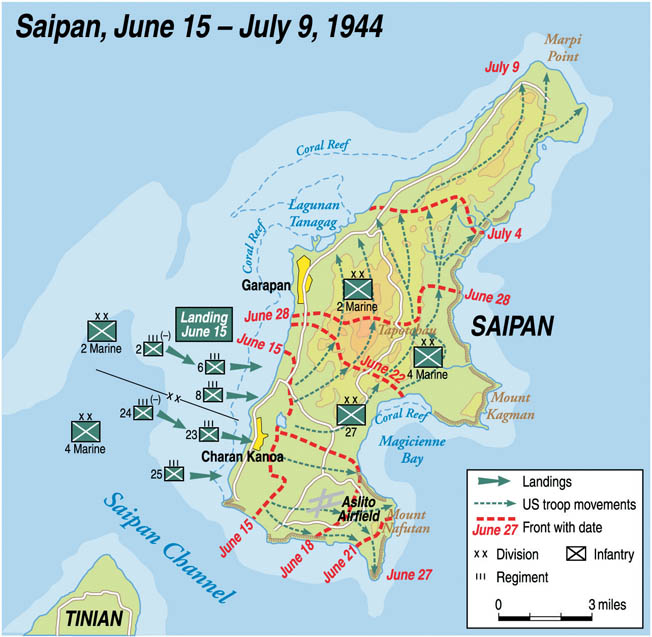

The American landing target was the four-mile long beachfront that stretched from a mile south of Garapan through Charan Kanoa and down to Agingan Point, just above the southwestern tip of the island. The beaches were designated Red, Green, and Blue, from north to south. The northern beach was the responsibility of the 6th and 8th Regiments of the 2nd Marine Division, while the 23rd and 25th Regiments of the 4th Marine Division would take the southern sector. Each battalion was responsible for about 600 yards of front.

The First American Wave

At 7 am, the shelling stopped, and 34 LSTs (Landing Ship Tanks) steamed up to the line of departure, two miles from shore, and began disgorging amtrac armored amphibious vehicles. More than 719 of them, jammed with eight battalions of Marines, headed ashore as 155 planes roared over them, strafing and bombing the beaches. The first wave of Americans hit the beach at 8:44 am.

Like a week before in Normandy on the other side of the world, chaos immediately reigned. The 2nd Battalion, 8th Regiment landed on Green Beach 1 instead of Green Beach 2, the 3rd/8th’s chosen assault site. Marines from the 6th Regiment landed on the wrong stretch of Red Beach. In a matter of minutes the commanding officers of all four invading battalions of the 6th and 8th Marines were wounded.

Saito had placed his guns well, keeping them concealed and in depressions to avoid destruction from American shells, and now they hammered the invaders. The shelling was so intense that the Americans thought the beach was mined. On the southern beaches, Yellow 1 and 2, the 25th Marines also came ashore under heavy fire. The 1st/25th Marines hit Yellow 2 Beach, and the battalion’s LVTs (Landing Vehicles Tracked) headed back out to sea without unloading ammunition, mortars, or machine guns. The battalion was pinned down for an hour. The 2nd/25th was able to get 700 yards inland, but the 23rd Regiment achieved only 100 yards inland.

Despite the heavy fire, the Americans refused to be dislodged from their beaches. With their usual determination and firepower, the Marines attacked into Charon Kanoa, it was the first time American troops had invaded a full-scale Japanese community. By noon, however, the 6th Marines had suffered 35 percent casualties, and the regiment’s boss, Colonel James Risely, aware that most of his senior officers were dead or wounded, assigned junior officers to take over higher duties.

Landing the M4 Shermans

Meanwhile, three companies of the 8th Marines faced Japanese guns and pillboxes in a woodland called Afetna Point, which enabled the enemy to pour enfilading fire on the Americans. The 8th Marines fought through pillboxes, shrubs, dense foliage, and Japanese troops. Company G of the 2nd/8th Marines had been issued a generous supply of shotguns, and the Americans used them with good effect against the Japanese.

South of Afetna Point, the 4th Marine Division pushed forward, struggling to gain a large concrete ramp that would be a perfect landing spot for the 46 gleaming new M-4 Sherman tanks, whose 75mm guns were superior to any Japanese machine, and a platoon of specially equipped flame tanks mounting Canadian Ronson flame guns that could spew a stream of fire up to 80 yards. The problem was getting the tanks ashore. Some of the tanks made it, but others never reached the shore, their landing craft sunk on the run-in by Japanese guns.

Although the tanks were having trouble coming ashore, the 4th Marine Division’s artillery was in battery soon after the landing. Two battalions of 75mm pack howitzers and three of 105mm howitzers were landed and began a spectacular artillery duel with Japanese guns, which gave the division’s commander, Maj. Gen. Harry Schmidt, some relief. His command post was a foxhole 50 yards from the water under heavy Japanese fire.

“I Couldn’t Even Shoot Anymore”

Life was no easier for the Japanese defenders. Sergeant Yamauchi and his pals were holding their ground at 2 pm when a second lieutenant came up, the adjutant from battalion headquarters. Yamauchi charged. Only two men joined him. “I suddenly felt something hot on my neck. Blood. I’m hit, I thought. But it was just a graze. I was too petrified to move. I couldn’t even shoot anymore,” Yamauchi recalled.

Realizing his attack was doomed, he ordered his two buddies to withdraw, but both were hit, one dead, the other wounded in the face. Yamauchi ran back to his trench alone to find the adjutant had disappeared, the rest of his squad still dug in.

Counterattack on the Beachhead

By sunset, 20,000 Americans had gained a beachhead some 10,000 yards long and 1,000 yards deep, half the terrain expected to be taken, manned by most of the two divisions supported by seven artillery battalions and most of two tank battalions. Several hundred Americans were dead.

Saito was confident, but his men were not. He ordered only 36 T-97 tanks and 1,000 infantrymen of the 136th Infantry Regiment, under Major Tirashi Hirakushi, a former public relations officer, to attack. Someone brought up the regimental colors to inspire the men. Yamauchi and his battered squad were told to hold the trenches while the rest of the men attacked.

Chaos reigned from the beginning. Hirakushi was relieved of his job of leading the attack and ordered to find the general, or at least his body. Another officer was assigned to head the attack at the last minute, which weakened unit cohesion. The new boss mounted the lead tank and ordered his men forward. Before the tank had gone half a mile, an American shell disabled it. Yamauchi heard his pals shuffling forward and fell asleep from exhaustion. The Americans were only 100 meters away.

With their usual ferocity, the Japanese infantry charged into the Marine defenses. As they lurched forward, the Marines lit up the sky with flares and .50-caliber machine-gun fire, waking up Yamauchi. The 6th Marines had heard the Japanese boots, tanks, clattering swords, and finally their bugles blaring battle calls. American machine guns began ripping into the Japanese attack. More than 700 Japanese soldiers died without gaining any ground.

Yamauchi decided he would play dead, lying face down in his trench. He had heard the Americans shot up Japanese corpses but was willing to take a chance to survive the battle. After several days, he rejoined a ragtag Japanese unit.

Attack on the Southern Flank

On the southern flank, the Japanese hurled a strong attack, backed by artillery and mortars, against the 25th Marines. The Japanese used civilians, including women and children, to mask their approach, and the Americans at first thought this was a civilian surrender. But when they neared the American lines, the Marines saw through the ruse and opened fire with 105mm howitzers, breaking up the attack.

Finally, at 5:30 am, about 200 Japanese charged for the Charan Kanoa pier, at the seam between the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions. The 3rd/23rd destroyed the enemy, but the Japanese were able to briefly grab the pier and damage it badly.

50% Casualties For Marine Officers

Tokyo was sending more help than inspiring words. The Combined Fleet had left its lairs in Japan and Singapore, bristling with guns, planes, and hate for Americans, and was headed for the Marianas. The Americans knew they were coming. Spruance delayed the June 18 date for the invasion of Guam and ordered the U.S. Army’s 27th Infantry Division to commence landing on Saipan.

As dawn broke on Saipan, the Americans resumed the offensive. They did not advance too deeply on this second day of the invasion, instead devoting their energy to consolidating their positions, mopping up, and most importantly, unloading the rest of the two Marine divisions and bringing ashore Maj. Gen. Ralph Smith’s 27th Infantry, starting with the division’s 165th Infantry Regiment, under Colonel Gerard W. Kelley.

Meanwhile, Japanese ferocity had a sharp impact on the battlefield. The 2nd Marine Division ended the day with half of its company and battalion officers dead or wounded. In the 4th Marine Division’s sector, Lt. Col. Maynard Schultz, boss of the 1st/24th Marines, was killed by artillery. Also impacted by Japanese shells were five companies of black Marines, the first employed in combat in the war, who came under fire while hauling ammunition and supplies to the front lines.

Another Japanese Armored Attack

That night, the Japanese tried to counterattack again. Saito sent in the 136th Infantry Regiment and Colonel Takashi Goto’s 9th Tank Regiment to launch a coordinated attack at 5 pm against the 6th Marine Regiment. The Navy’s 1st Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force would take part as well. But his men were so disorganized, the attack did not go in until 3:30 am, with Goto himself saddling up in his command T-97 tank and infantrymen riding the huge vehicles, some blaring bugles.

When the Japanese tanks lumbered toward battle, they made a vast noise that alerted the Marines and worried Jones. He had been told the Japanese might have as many as 200 tanks on Saipan. It sounded to him like all 200 were headed straight for him.

In their dugouts, the Marines watched as the tanks rolled over and past them. Captain James Rollen leaped out of his foxhole and fired a grenade launcher at a T-97. It bounced off, and Rollen staggered out of the battle, eardrums damaged by concussion. Captain Norman Thomas took over moments later and was quickly killed.

As dawn broke, so did the Japanese attack. The surviving Japanese began retreating toward Mount Tipo Pale, while an offshore destroyer hurled shells after them, blasting a surviving tank. The Marines counted 31 wrecked T-97s and the bodies of more than 700 mangled Japanese soldiers and Marines, for a loss of about 70 leathernecks.

Advancing Across Saipan

Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith now cut orders to have the 2nd Marine Division be the northern pivot of a wheeling attack by Maj. Gen. Harry Schmidt’s 4th Marine Division, which would push across the farmlands of southern Saipan to the east coast at Magicienne, then drive northward into the central highlands. The 27th Infantry would operate on the 4th Division’s flank, reaching for Aslito Airfield. Once that was accomplished, the three divisions would undertake the daunting task of storming Mount Topatchau and driving across the island to the northern peak at Marpi Point.

Loud, crusty, and opinionated, Holland Smith had a common touch and concern for his Marines. Admiral Spruance provided regular gifts of five-gallon drums of ice cream from his ships’ reefers, and every time they arrived Smith would shout out from his front window that any leatherneck in earshot should hurry over for the ice cream.

Steadily the Marines and GIs began their advance across Saipan. Under their boots and vehicles, the island’s dirt roads turned to dust and mud. The southern third of Saipan was dominated by well-tended farms and villages, which grew sugar cane, corn, peas, cantaloupe, and potatoes.

At his tactical headquarters, Saito, having recovered his composure, studied his maps on the 17th and determined that he could not hold southern Saipan until the Imperial Navy had steamed up, smashed the American fleet, and relieved the garrison. Nevertheless, Saito was determined to hold the island, slowly retreating, buying time, and inflicting casualties.

Capturing Conroy Field

On the 18th, Holland Smith ordered his three divisions forward to sweep the southern portion of Saipan and take Aslito Airfield, enabling land-based planes to operate from Saipan. The 165th Infantry Regiment drew the assignment and went forward with artillery and tank support. At 10 am, the troops crossed the airfield and pronounced it secured 16 minutes later.

The airfield was renamed Conroy Field in honor of Colonel Gardiner J. Conroy, who had commanded the 165th in its invasion of Makin and been killed there. The Marines soon renamed it Isely Airfield after a naval aviator who had been shot down over Saipan. The 165th moved on toward Nafutan Ridge, where they came under heavy Japanese fire.

Meanwhile, the 4th Marine Division advanced in the face of intense Japanese machine-gun fire and a sudden counterattack by two tanks. The tanks caused 15 casualties before they were driven off by bazookas and artillery.

That same day the Japanese made their major effort to defeat the U.S. Navy at the Battle of the Philippine Sea and suffered immense losses, withdrawing from the scene.

Nafutan Point

The next American land objective was Nafutan Point, a short peninsula dominated by a high, craggy ridge, and Mount Nafutan, which stood 407 feet high. The Japanese defenders numbered about 1,050 men from the remnants of the 317th Independent Infantry Battalion and the 47th Independent Mixed Brigade along with some other stragglers. Behind them were frightened Japanese civilians. In command was Captain Sasaki, boss of the 317th.

The 27th Division was given the job of clearing Nafutan Point and came under heavy fire from Japanese pillboxes. The 105th Infantry tried to place shaped charges against the pillboxes to blast them open, but the fire was too heavy. The Americans tried outflanking the enemy, struggling through an exploding Japanese artillery dump. The 165th struggled through a slope made up of a coral formation studded with sharp rocks, pocked with holes, deep canyons, crevasses, and caves, overgrown with vines, small trees, and bushes. Fortunately, the natural defenses were tougher than the Japanese.

After dark, the Japanese tried a 20-man counterattack, which was broken up. A group of 20 to 30 civilians stumbled into an American position and all were killed.

On June 20, Ralph Smith’s GIs continued to struggle to gain Nafutan Point, using smoke screens to conceal their flanking movements. When the 1st Battalion of the 105th Infantry came under Japanese fire from snipers in a town, Lt. Col. William O’Brien, commanding the battalion, ordered the settlement burned down, with tanks, antitank guns, and flamethrowers doing the job. With artillery and tank support, the GIs steadily squeezed the Japanese, suffering light casualties, one man dead in the 105th and six in the 165th. With two regiments of the 27th engaged, the division’s third regiment, the 106th, finally came ashore to serve as corps reserve. Meanwhile, the two Marine divisions pivoted on the invasion beaches to prepare for the big drive to clear the island from south to north.

On the 21st, the 27th continued to attack Nafutan Point. At 9:30 am, the 1st/105th moved forward slowly without opposition, but at 12:55 pm it came under heavy mortar and automatic weapons fire in open terrain. The GIs withdrew and summoned tanks. On the 27th’s extreme left, the fresh 2nd/105th, under Lt. Col. Leslie M. Jensen, went into attack in extremely difficult terrain, facing the nose of Mount Natufan, a sheer cliff that split the battalion front like the bow of a ship. The cliff was only 30 feet high, but the approach to it was a steep slope through a cane field’s stubble, which lacked cover.

The battalion jumped off on schedule at 9:30 am and was immediately hit by the usual small arms, machine-gun, and mortar fire. The Americans assaulted the cliff and reached its top, but could not hold on. Jensen called for rations, water, and artillery, which fired at point-blank range. The Americans ultimately forced the Japanese to withdraw.

Slow Advance Toward Smith’s Line

However, the American advance was still moving slowly. On the 22nd, at 6 am, the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions, backed by 18 battalions of artillery and naval and air support, launched a coordinated attack and made substantial gains on the lower slopes of Mount Tapotchau. The Marines faced counterattacks and heavy enemy fire, which was aggravated when a Japanese ammunition dump exploded

Back at Nafutan Point, the 105th Infantry struggled against the Japanese, gaining little ground. Holland Smith warned Ralph Smith that if the 105th did not advance he would fire its colonel. Ralph Smith responded that the Japanese were holding difficult terrain.

Meanwhile, the battle raged on. Holland Smith ordered the 27th Division into the main attack, leaving Nafutan to a single rifle battalion and a platoon of six light tanks and very little artillery amid mountainous terrain.

Studying his maps, the 4th Marine Division’s commander, General Harry Schmidt, regarded Holland Smith’s plan as overly optimistic and penciled in a line for reorganization 2,000 yards short of Holland Smith’s objective line. Even so, the Marines struggled to reach the line on Schmidt’s map.

“Death Valley”, “Purple Heart Ridge”, and “Hill Love”

On the 23rd, the Army’s 106th and 165th Regiments were ordered to attack a ridge north of their lines and a valley just west of it. The 3,600 Japanese defenders were from two units, the 118th and 136th Infantry Regiments. The Americans would come to name the valley “Death Valley” and the hills “Purple Heart Ridge.”

Seven American regiments, two Army and five Marine, would make the assault. The first American objective was “Hill Love,” and the 1st/165th led the way with a platoon of tanks from the 762nd Provisional Tank Battalion. The 3rd/165th tried to attack a little cove in the mountain wall studded with Japanese machine guns and their crews.

The Battle of the Caves

What the Army would call the Battle of the Caves raged on ferociously. The 762nd Tank Battalion sent 72 Shermans into action—only 18 were left at the day’s end. The 3rd/106th came under Japanese mortar fire that took 31 men in less than a minute.

Watching this futile attack, Holland Smith fumed over the Army’s poor showing. Studying the island from the 1,554-foot Tapotchau summit with a powerful Japanese telescope he found there, Holland Smith assessed Saipan’s mountains and valleys. His Marines were taking a pounding but taking ground. The 2nd Marine Division had lost 2,514 men, while the 4th had lost 3,628. The 27th Division’s two fresh regiments would now have to be the main assault force.

Two Branches, Two Different Tactical Approaches

Now the differences between the Marine Corps and Army approach to war began to plague the American drive. Holland Smith and his Marines stressed high-cost frontal assaults and relied on speed, aggression, and violence to achieve their goals. Ralph Smith and his GIs favored the Army’s standard holding attack, which relied on one force holding the enemy under pressure while a second force outflanked the defenders, relying on movement and firepower.

Holland Smith believed the 27th was “flat and listless,” and he blamed Ralph Smith. He called in Army Maj. Gen. Sanderford Jarman, who was to take command of the island once it was secured and ordered him to visit Ralph Smith and convey the corps commander’s displeasure. Holland Smith warned Ralph Smith that if the 27th was not an Army Division “and there would be a great cry sent up more or less of a political nature,” he would immediately relieve Ralph Smith.

Holland Smith gave his subordinate one more day to make progress, but the Japanese were as stolid and ferocious as ever. The 5th Amphibious Corps attacked on Saturday, June 24, with the 8th Marines digging Japanese positions out with satchel charges, bazookas, and flamethrowers.

At least the Marines had a sense of progress, despite suffering 812 casualties in the 4th Division over the 23rd and 24th and 333 in the 2nd for the same two days.

Meanwhile, Saito had angled his defenders to give a rough reception to the 27th Infantry in Death Valley, which in turn fronted Saito’s headquarters. The Japanese general was determined to hold on, and he had 4,000 men backed by most of the 9th Tank Regiment’s T-97s in position to do so. All of his caves deployed machine guns, mortars, or 75mm guns.

“Start Moving at Once”

As June 24 dawned, Ralph Smith moved through his frontline units, personally directing the assault. The 165th Infantry jumped off right on time at 8 am, seeking to storm Purple Heart Ridge—actually a series of hills connected by a ridgeline running in a northerly direction. The two lead battalions came under heavy fire, and many men were pinned down or killed. One battalion only advanced 150 yards for the entire day.

The 106th headed into Death Valley and came under such heavy mortar fire that many GIs had to fall back behind the line of departure. Ralph Smith radioed his commanders: “Advance of 50 yards in 1½ hours is most unsatisfactory. Start moving at once.”

Jarman Takes Command of the 27th Infantry

Around noon, a Marine jeep pulled up at 27th Infantry Division’s forward command post, and a captain of the adjutant general’s staff hopped out, saluted, and handed Ralph Smith a sealed envelope. Inside was a terse message from Holland Smith relieving Ralph Smith of his post. Maj. Gen. Jarman was to take over the 27th immediately.

Controversy would rage over this abrupt mid-battle dismissal, but the changes at the top did little to change the situation on the ground. Holland Smith’s three divisions had now created a U-shaped front, with the 27th in the base of the U.

Jarman studied the maps and plans inherited from Ralph Smith and decided to use them, pushing the 106th Regiment eastward toward Chacha Village and then swerving northward to flank Purple Heart Ridge. But as the 106th did so, it came under murderous fire from Saito’s well-protected 31st Army headquarters. The 106th Regiment was stalled by difficult terrain and determined Japanese fire. Jarman asked Ayers why the 106th did not skirt the eastern slope of Purple Heart Ridge or make any progress, and Ayers could offer neither excuse nor “explanation of anything he did during the day,” Jarman reported later. “He stated he felt sure he could get his regiment in hand and forward the next morning. I told him he had one more chance and if he did not handle his regiment I would relieve him.”

The attack up Death Valley did little better. Jarman ordered artillery hurled directly against Hell’s Pocket and Mount Tapotchau, but the Army made no progress. Short of water, food, and ammunition, the exhausted troops pulled back, wounded men being carried by their buddies.

Driven Off Mount Tapotchau

The Marines, however, did better. The 4th Marine Division finally occupied the whole of Kagman Peninsula, cutting the front down by 3,000 yards, while 2nd/8th Marines and 1st/29th Marines fought for Mount Tapotchau, the island’s highest point. Pushing off at 7:30 am, the leathernecks worked their way up to the top by scaling the cliffs. The Army had drawn off so many Japanese defenders to the sides of Tapotchau and Purple Heart Ridge that the Marines were able to reach the top almost unmolested.

Saito appreciated the situation as well, understanding the mess he was in. As he moved his tactical headquarters from Mount Tapotchau to a small cave one mile north of the lost pinnacle, he had only 1,200 able-bodied men and three tanks left of all Japanese Army frontline units.

On the 26th, the Japanese tried a predawn attack against the 1st/6th Marines. It failed.

The Americans continued their offensive. The Marines had turned the U-shaped salient into a death trap for the Japanese men defending it, and the 27th Infantry continued its bloody struggle for Purple Heart Ridge. The 106th Infantry sent in M7 self-propelled howitzers, Sherman tanks, and finally M-8 self-propelled artillery to chisel the Japanese out of their cliffs and caves. The 104th Field Artillery lobbed 360 rounds of 105mm shells into the Japanese positions, but the Japanese kept up heavy return fire. Seeing the 106th unable to gain ground, Jarman kept his promise and fired Colonel Ayers, appointing division chief of staff Colonel Albert K. Stebbins as regimental commander.

The Marines made small gains on Purple Heart Ridge, but mostly the leathernecks took a breather before resuming the assaults the next day.

“Seven Lives For One’s Country”

Far to the south, 500 Japanese troops, isolated by the 105th Infantry on Nafutan Point, lined up to make a midnight charge against the Americans. Captain Sasaki, commanding the 317th Independent Infantry Battalion and the other trapped forces, told his men, “The password for tonight will be ‘Seven lives for one’s country.’”

The Japanese infiltrated through the American lines and at 2:30 am on the 27th hit Aslito Airfield and the emplacements of Marine artillery units. The Marine gunners fired their weapons at point-blank range or reached for their rifles and grenades, fending off the enemy. The 14th Marine Artillery Regiment killed 143 Japanese at the cost of 33 killed and wounded.

On the 27th, Jarman ordered his GIs to reorient their attack. He had only four battalions under his control—Holland Smith was giving direct orders to the rest—but Jarman was determined to clean up Death Valley with the 106th Infantry. The 3rd/106th attacked at 6:20 am and came under immediate machine-gun fire, forcing the GIs to retreat. At 10:20, division ordered 25 minutes of artillery fire, but the artillery spotters had to hold their fire for half an hour trying to figure out where the American troops actually were to avoid hitting their own men.

Following the artillery barrage, the Americans attacked, and this time found a litter of enemy dead and not a shot fired. They moved through the terrain and up Hill King, finding a party of Japanese hiding in rocks and grass. The Americans threw grenades and pulled back to allow their mortars to destroy the position. Hill King was in American hands.

“A Handful of Japs”

The 3rd/106th kept moving through Death Valley, through cane fields, into the floor of the valley, pushing ahead despite heavy fire and shortages of ammunition and water. A platoon of light tanks was dispatched to provide the infantrymen with covering fire and supplies. Joined by the 165th, the 106th Infantry steadily attacked across Death Valley, getting into a severe hand-to-hand fight that left seven American casualties and 35 Japanese killed. The 1st/106th was assigned to mop up Hell’s Pocket.

The 4th Marine Division continued its advance on the right backed by 1st/165th, 3rd/165th, and 1st/105th from the 27th Division. The 4th Marines moved ahead rapidly. The 2nd Marines made slower progress, reaching the outskirts of the capital, Garapan.

Meanwhile, Saito, Nagumo, the 31st Army’s chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Keiji Igeta, and other top Japanese officers convened to figure out what to do. It was decided simply to delay the Americans as long as possible.

Holland Smith was annoyed that the 105th had progressed so slowly against “a handful of Japs.” He had a point—American leadership had been halting and slow, coordination poor, but the Japanese were in strong defensive terrain. The slow advance added to Holland Smith’s gripes against the Army and Ralph Smith.

On the 28th, the 27th Infantry Division got its third new boss in a week, as Maj. Gen. George Griner was sent out from Hawaii to take over the division from Jarman. He inherited a division still struggling to finish off Purple Heart Ridge. As usual, the Japanese defenders did not open fire until the Americans were practically on top of them. Finally, however, Hell’s Pocket was cleaned out.

The Marines advanced slowly, battling terrain and Japanese defenses. American fighter bombers added to the horror with a misdirected airstrike that hit the 1st/2nd Marines with three rockets, causing 27 casualties.

Taking Fourth of July Hill on Independence Day

The next day, June 29, the Americans continued to grind their way northward with the Marines driving on the flanks, isolating the Japanese defenses. The Marines advanced slowly into Garapan.

Under Griner, the 27th fought better. At 2 pm, three of the division’s battalions jumped off to attack the northern end of Death Valley with Holland Smith himself watching from Mount Tapotchau. The Marine general was pleased and “expressly complimented” the division’s performance to Griner.

On the last day of June, the 27th finished its bitter struggle to capture Death Valley and Purple Heart Ridge. “No one had any harder job to do,” said Marine General Harry Schmidt later. Fighting raged on in Garapan. GIs assaulted Hill Uncle-Victor backed by heavy artillery fire, advancing 400 yards and finally clearing out Death Valley.

Sergeant Takeo Yamauchi was ordered to withdraw with his pals in single file amid pouring rain. American troops opened fire on them, knocking Yamauchi’s glasses off his face. He and some buddies hid in a bunch of rocks, staying there until July 3.

The Americans now moved on the major town of Tanapag, finally looking down on it from the high ground. The 2nd Marine Division secured Garapan, finding Saipan’s capital a mass of rubble from artillery fire.

On July 2 and 3, the Japanese continued to retreat in a piecemeal manner, while the Americans picked their way slowly and carefully behind them. The 24th Marines stormed Fourth of July Hill but were forced back each time by Japanese machine guns and mortars. The leathernecks pulled back and let the artillery take over, pounding the hill all night long. By 11:35 am on Independence Day, Fourth of July Hill was in American hands.

Hara-Kiri Gulch

The American advance continued in a heavy downpour, which mired the tanks, but the 1st/165th reached the top of the last ridge over Flores Point seaplane base. In the Army’s center, the 106th Infantry Regiment fought into the seaplane base joined by the 8th Marines.

Saito set up a new headquarters in the valley south of the village of Makunsha named Paradise Valley by the Americans and Hell Valley by the Japanese.

Holland Smith now had his plans ready for the third and final phase of the Saipan drive. The objectives were now Marpi Point and Marpi Airfield at the northern tip of Saipan.

With the island narrowing, he could not put three divisions in the line, so he pulled out the 2nd Marine Division to rest and prepare for the coming invasion of Tinian. The 4th Marine Division would advance on the right, 27th Infantry on the left. The Army assault would begin on July 5.

The attack went in at 1:30 pm with the usual opening barrage of artillery and air attack. The 27th Infantry attacked a canyon 50 yards wide and 400 yards long covered with undergrowth and trees. An ideal position, the Americans named it Hara-Kiri Gulch.

Company K of the 165th hit Hara-Kiri Gulch first, doing so with tanks. Japanese troops darted out from ditches and slapped mines on the tanks, which disabled them. The Americans sent in more tanks and made repeated attacks, but the Japanese returned heavy fire.

“We Three Will Commit Suicide”

Among the 200 to 300 defenders of Paradise Valley was Sergeant Takeo Yamauchi. He and two other soldiers stayed concealed there through July 8. He told the two men sharing his dugout that Japan was going to lose the war.

Saito told an assembly of officers that the final stand was at hand. That evening, the headquarters group ate the last of their food. Hirakushi asked if Igeta and Saito would participate in the final assault. Nagumo, who had said almost nothing during the whole retreat, finally spoke for the three officers: “We three will commit suicide.”

Tanapag Falls to the 27th

At dawn on July 6, the Americans resumed the offensive. They were beginning to sense victory. Most of the island had been taken, and while Japanese defense remained fierce it was uncoordinated, splintered, and steadily weakening.

Company K of the 105th Infantry, under 1st Lt. Roger Peyre, joined by a platoon of light tanks under 1st Lt. Willis K. Dorey, attacked through a deep gully at 10:30 am and came under heavy Japanese fire. Peyre’s men moved out of a coconut grove into a counterattack down a cliff that was climaxed by a gigantic explosion that sent Japanese bodies and limbs in all directions.

All day the Americans continued their drive. The 27th captured Tanapag, the last significant town on Saipan. That evening, the 1st and 2nd/105th deployed in an elongated semicircle. The 3rd/105th camped inland and several hundred yards south of the other two battalions. The GIs did not know it, but the artillery of 3rd/10th Marines were setting up behind them to bring Marpi Point under fire.

At Saito’s cave, a sentry reported that an enemy tank was “peering over” the edge of the cliff above. Saito, conferring with Igeta and Nagumo, summoned Hirakushi and told the major that the three flag officers intended to commit suicide at 10 am. Command of the final assault would devolve upon Colonel Eisuke Suzuki of the 135th Infantry Regiment.

One Last All-Out Attack

When Hirakushi woke from a deep sleep, it was past sunset. He found his soldiers and sailors assembling outside, armed with rifles, swords, and even bamboo spears as officers sorted them into groups in the moonlight to the line of departure. More than 3,000 Japanese including civilians entered the coastal plains. Hirakushi heard Japanese troops shouting battle cries, and then rifle fire sputtered from a ridge signaling the attack. Hirakushi’s men charged down the beach toward Tanapag without waiting for the command, and the major followed his men. As he charged, an explosion surrounded him. Then he passed out.

The Americans knew something was coming. A single prisoner had divulged the Japanese intent, saying that they were planning an all-out attack before dawn by everyone who could carry a rifle or spear.

The Japanese stormed over the two defending Army battalions, killing or wounding 650 GIs. Another group of Japanese troops stormed through a winding canyon and into the 3rd Battalion, but these Americans were too well emplaced and could not be dislodged.

As the Japanese attack flowed south, Marine artillery deployed behind the GIs opened fire, knocking out a Japanese tank, but the enemy stormed through to the gunners’ emplacements. The assault forced the Americans back into the streets of Tanapag. For the next four hours, the GIs, out of communication with their command posts, short of ammunition and water, with no means to evacuate wounded men, hung on against repeated Japanese attacks.

Smith responded with massive force. Navy cruisers sprinted to the scene and hurled shells at the beaches. An Army tank unit finally entered the fray. American artillery fired at anything that moved, driving American troops into the water. Griner sent his 165th Infantry Regiment to attack the Japanese on their right flank, into Hara-Kiri Gulch, driving the enemy out of the plain.

By mid-afternoon, the Japanese attack petered out against determined American defense and overwhelming firepower. Army and Navy medics passed through the many scattered bodies and found surviving Japanese. On a U.S. Navy hospital ship, Major Hirakushi woke up, bandages on his head and shoulder, and his left hand handcuffed to a bed.

Suicides on Saipan

As the Americans regained the ground lost in the initial Japanese assault, Holland Smith pulled the battered 27th Infantry Division out of the line and assigned the Marines to finish off the defenders. The 2nd Marine Division began mopping up, attacking on the 7th at 11:30 am. The 6th Marines found a pocket of resistance of about 100 Japanese troops, who finally succumbed around 6:30 pm. All day long on the 8th and 9th, the 8th Marines investigated caves, finding disorganized Japanese groups dug in.

On July 9, the 4th Marine Division grabbed the ridge that overlooked Marpi Point and the cliff wall that fronted the sea. Saipan was secured.

At Marpi Point, a plateau some 833 feet above a shore of jagged coral rocks, 5,000 men, women, and children were trapped by the Marines. Fearing horrible deaths and eternal shame at the hands of the leathernecks, the Japanese civilians began killing themselves. Whole families waded and swam out to sea to drown themselves. The orgy of suicides went on through July 12.

Sergeant Takeo Yamauchi Surrenders

Some Japanese men held out, among them Sergeant Takeo Yamauchi, whose dugout was ignored on the 8th and 9th. On July 10, American warships fired on his area, killing one of his men. Yamauchi suggested to his crew that they swim out to where the bow of a sunken ship was jutting out of the sea, but most of the men were no longer responding to rank and authority.

That evening, Yamauchi and some like-minded pals tried to swim to the ship, but the waves were too strong and most of the men turned back to shore. Just one sailor and Yamauchi were left in the water when an American machine gun opened fire. Yamauchi and his sailor colleague found a cave with a sergeant, several soldiers, and about 20 Japanese civilians, including women with crying babies. They huddled in the cave under a road. Late on the 13th, Yamauchi slipped out of the cave and made his way to a tree, planning to surrender at daybreak.

There he found four Japanese civilians—a middle-aged couple, a man a little older than himself, and a teenage girl. The middle-aged woman gave Yamauchi some porridge in an old tin can, his first meal in days. Then he just stood up and walked off through the jungle, the teenage girl and the couple following him. A Marine appeared in the jungle and ordered Yamauchi’s party to halt and took them all prisoner.

“Hell is Upon Us”

Scattered fighting and roundups continued on Saipan for weeks—it was not until August 10 that the Americans could truly say the island was secure. By then, the Americans were moving on Tinian and Guam.

With the island of Saipan in hand, it was time for the Americans to tally the cost. More than 70,000 Americans took on 30,000 Japanese. The Americans had lost 3,225 dead, 13,061 wounded, and 326 missing. The Japanese losses were even greater. The Americans buried 23,811 Japanese defenders and took 1,780 prisoners, including 921 Japanese (17 of them officers), and 838 Koreans.

The loss of Saipan sent terrible shockwaves through Japan. The nation was already reeling from the naval debacle in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Privately, the Japanese leadership was also less bombastic. Admiral Shigeyoshi Miwa, describing the impact of the loss of the Marianas to Japan, put the situation succinctly to the emperor, saying: “Hell is upon us.”

Originally Published December 29, 2016

Updated March 7, 2017

Nice read.

I am trying to trace my father’s footsteps. He passed a few years ago with very little detail and his military records were destroyed in a fire at the Defense Dept.

He was in the 27th Infantry. I don’t know which regiment, but either the 165th or 106th from reading your piece.

My father was an Infantryman in the 27th Division on Saipan during the battle … he was in Headquarters Company … served as a.30 Cal Machine Gunner … survived the Banzi Attack … near the end of the battle … I am pleased to meet anyone … who had relatives or anyone who served in the 27th Division during the battle.

Danehy A Carson

I’m trying to trace my father’s campaigns in the Pacific . I’ve found his name in the roll call of the Presidential Unit Citation 6th Division at Okinawa , 3rd Amphibious Unit . recognizing the patch that he had . I’ve also seen a penciled drawing of the Island of Saipan , penciled from atop a troop transport . I’m looking for the Division he was in before the 6th was formed on Guadalcanal ! My father didn’t talk about the war ! He passed in 1992 . His name was listed in the roll call as Sams Charles . Charlie Sams Jr. Was later recalled during The Korean War . Stationed in San Diego as a hand to hand instructor . at the rank of Sergeant

When I was in Japan on business my hosts took it upon themselves to say to me that WWII was not “fair” to Japan – “seven nations against Japan”, “only country to have an atomic bomb dropped on it.. ” like they felt that somehow war had to be “fair”…. These people were a racist lot too but they were my hosts… so I did not want to be impolite… The story of how difficult it was to take Saipan and the costs involved are but one of many justifications for the use of the atomic bomb to end the war… I wanted to end this ridiculous conversation so I asked them… “why did Japan start the war” … their answer after conferring with one another was “Japan thought they could WIN the war” .. My sharp and loud response was “Japan was WRONG”… they then agreed that war was a very bad thing…. Too bad the Japanese could not have come to this conclusion in the 1930’s / early 1940″s….. The expenditure of blood and treasure to take Saipan again was one of many very valid justifications to use Atomic Weapons on Japan… but the context of historical fact seems to be lost on people – not by any means on me. It makes people like Pierre Dupont, Graves and Oppenheimer to be hero’s… for the countless lives they saved. The Japanese both earned and deserved to have atomic weapons dropped on them…

No country deserves to have atom bombs dropped on them. Not all Japanese were bad,to many innocent people who did not want a war died. Japan was on the verge of defeat but the yanks just had to try out the atom bombs on someone.

The Japanese were ready to commit national suicide after the second bomb at Nagasaki. It the Emperor had not told them to surrender, millions more would have died. Read up just a bit more on your history.

If the atomic bombs had not been dropped the napalm bombing which had been devastating Japanese cities would have destroyed many more cities and killed many more civilians and an invasion would have killed many more Japanese soldiers and civilians and American soldiers. The Atomic bombs saved many lives.

Why is there no mention of the “Wind Talkers” in the Battle for Saipan?