By Ray Argyle

Flying a tortuous route from North Africa tothe French coast of Normandy via Casablanca and Gibraltar, an unarmed Lockheed Lodestar of the Free French Air Force broke through cloud cover over the English Channel on the morning of Sunday, August 20, 1944.

The plane carried Free French leader General Charles de Gaulle, bound for a crucial meeting in Cherbourg with General Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander of Allied forces in the invasion of Europe. “I left for Paris,” General de Gaulle would write laconically in his Mémoires de Guerre,of the day he flew out of Algiers. He was returning to France with but one mission: to seize Paris in time to save it from a Communist takeover or from last-minute destruction by the fleeing Germans.

The Lodestar pilot, Colonel Lionel de Marmier, uncertain of his bearings, asked for permission to land in England. “Non,” replied de Gaulle, peering at a road map on his lap as he tried to identify a familiar landmark. With the plane’s gas tanks nearly empty, de Gaulle sighted the landing strip at Maupertuis, south of Cherbourg. “La-bas [over there],” he signalled, pointing to the ground. The Lodestar’s engines coughed out their last ounces of fuel as the plane thudded to a landing. Safely on the ground, de Gaulle received an ominous report from General Marie-Pierre Koenig, head of the Free French Forces of the Interior (FFI). “There has been an uprising in Paris. We need to move quickly.”

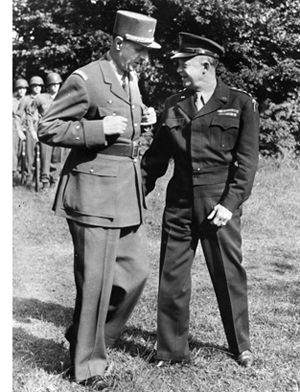

Two hours later, de Gaulle was at Eisenhower’s headquarters. The pace of the Allied advance was picking up all along the front, General Eisenhower told de Gaulle. The U.S. First Army under General Courtney Hodges was about to leap the Seine River north of Paris, while General Bernard Montgomery’s British and Canadian forces were advancing toward Rouen on the east bank of the Seine.

De Gaulle was surprised to hear no mention of Allied plans to occupy Paris. “I don’t see why you cross the Seine everywhere, yet at Paris and Paris alone you do not cross.”

This was the first meeting of the two generals since before D-Day and both were edgy and tired. The Allies did not want to risk the destruction of Paris and the heavy loss of civilian life that might come from a direct assault, General Eisenhower explained. It would be preferable to bypass the city, returning to it afterward.

“The fate of Paris is of fundamental concern to the French government,” de Gaulle told the Supreme Commander. If necessary, he would order the Free French 2nd Armored Division into Paris on his own.

General de Gaulle’s difficult relations with the Allied commander were well known. Since 1940, he had been struggling to assemble his country’s forces in opposition not only to Germany but also to the traitorous government of Marshal Philippe Pétain that had installed itself at Vichy after the French defeat. Now, four years and two months later, de Gaulle was in control of much of the old French Empire as the undisputed leader of the Free French and their army, navy, and air force that were fighting under the French Tricolor and the Cross of Lorraine. By the end of the war, the Free French would have two million men in arms.

De Gaulle’s proudest achievement was the building of the French 2nd Armored Division, which he had entrusted to a titled French patriot, Jacques-Philippe Leclerc de Hautecloque. It had become de Gaulle’s strongest striking force and had joined other Allied troops in Normandy on August 1. Four French divisions had fought with valor in Italy, and the French First Army had landed on the Mediterranean coast, along with the U.S. VI Army Corps, just a week before de Gaulle’s arrival in Normandy.

The French general’s claim to equal treatment as an Allied war leader and his insistence on reclaiming his country’s “grandeur” was a cause of unending friction among the Allies. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, while sympathetic to de Gaulle, acceded to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s distrust of the Free French leader. The president leaned toward putting liberated France under an Allied military government as an alternative to what he saw as an incipient de Gaulle dictatorship.

All of these factors, plus the decision to exclude de Gaulle from D-Day planning, made for testy relations. There had been a ferocious blow up when de Gaulle, invited to England just ahead of D-Day, refused to provide liaison officers to assist Allied forces unless he was assured they would be recognized as the supreme civil authority in liberated territory.

This idea conflicted with President Roosevelt’s dictate that the French people should have the opportunity after the war to choose, if they wished, a government other than one headed by de Gaulle. A “School of Military Government” had been set up at the University of Virginia in 1942 to train officers to manage civil affairs in former enemy-occupied lands. These “60-day marvels,” as they came to be known, would face insurmountable tasks without the support of French administrators.

General Eisenhower handled the crisis skilfully. He obtained approval from the president to consult with the Free French on civil administration with the caution that “such dealings shall not constitute recognition [of a de Gaulle government].” After backing away from Roosevelt’s plan for a military administration of France, he turned his attention to dealing with the powerful German forces still entrenched there.

Since D-Day, the 56 German divisions that awaited the Allied assault had been reduced to 40, many mere skeleton forces. After the closing of the Falaise Gap, which saw the capture of 200,000 Germans and 50,000 dead, General S. George Patton hoped to lead the U.S. Third Army in a dash for the Rhine while General Montgomery’s British and Canadian forces pushed up the coast toward Belgium and Holland.

As Paris held no strategic military value, a pincer movement around the city was contemplated. Allied military planners had no desire to take on the job of maintaining order in Paris or of feeding the city’s five million hungry inhabitants. This would require the diversion from the front lines of 4,000 tons of food and supplies daily, something the hard-pressed U.S. Quartermaster Corps hoped to avoid.

As de Gaulle and Eisenhower talked through Sunday morning in Cherbourg, a full-scale uprising of the French Forces of the Interior—the Resistance—was underway in Paris. Barricades were going up, and German troops were being picked off by Resistance fighters armed with seized weapons. General Dietrich von Choltitz, the German commander of the Paris garrison, was weighing Adolf Hitler’s command that “Paris must not fall into enemy hands, or if it does, only as a field of rubble.” Choltitz told Swedish diplomat Raoul Nordling, “I am a soldier. I get orders. I execute them.”

The uprising had been forced on the French Committee of National Resistance (CNR), the united underground assembled by de Gaulle delegate Jean Moulin, by the Communist leadership of the Paris Liberation Committee. “Paris is worth 200,000 dead,” declared Colonel Rol-Tanguy, its Communist head. Gaullist members of the CNR, fearful of letting the Communists take ownership of the uprising, had no choice but to back the rebellion.

After walkouts by Metro drivers, postmen, and telegraph workers, the city’s 15,000 policemen went on strike. On Saturday, the day before General de Gaulle’s return to France, they seized the Prefecture of Police on the Ile de la Cité. “The hour of liberation has come,” a police order declared. That day, a German Tiger tank had attacked the Police Prefecture, and 50 Germans had died in the fighting.

Nordling, as a representative of neutral Sweden, was in a position to negotiate with both sides. He met with General Choltitz to work out a truce, telling him that the Resistance was mainly against the French Vichy government that had been cooperating with Germany. The truce the two arranged provided for the Germans to recognize the French Resistance fighters as regular soldiers, not as terrorists. Not only that, the Germans would make an orderly evacuation from the city. The Resistance reluctantly accepted the truce, but sporadic fighting continued.

By midweek, 400 barricades had made the streets of Paris virtually impassable to heavy trucks or tanks. At each, young men—and some young women—clambered about, proudly displaying FFI armbands or bits of military uniforms picked up from dead Germans. To existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, the uprising was “a symbolic rebellion in a symbolic city.” Those who could not play in the Resistance “felt left out of the game.”

Knowing that only the arrival of French forces would prevent further fighting, Nordling got Choltitz’s permission to send a secret mission through the lines to advise General de Gaulle to come quickly. At the same time, Rol-Tanguy agreed to send his chief of staff, Major Roger Gallois, through the Allied lines. Traveling with a Paris doctor who had a Red Cross pass allowing him safe passage, the two drove to a sanatorium in Bretèche, 20 miles west of Paris.

Just before dark, Gallois slipped through a forest and found himself at an American forward base. Several hours passed before he was interviewed by an intelligence officer who recognized the value of Gallois’s information. An uprising was underway in Paris, barricades were being erected, and the German high command had accepted a truce. Major Gallois was brought before a sleepy General Patton at 2 amon Tuesday, August 22. A lively discussion ended with Patton producing a bottle of champagne and offering a toast to victory.

General Eisenhower received Patton’s account of this new disclosure as he was reading a fresh letter sent to him by de Gaulle urging a move on Paris. The French general was keeping abreast of events unfolding in Paris via messages from the Resistance and from Underground newspapers that were being printed in the capital. Devouring the first uncensored papers to be published in Paris since the start of the occupation, de Gaulle was “pleased by the spirit of the struggle” reflected in their columns.

Emboldened by what he was reading, de Gaulle prepared his letter for the Supreme Commander. “The information I have received from Paris today,” he wrote, “makes me think that in view of the almost complete disappearance of the police and of the German forces in Paris and the extreme shortage of food there, serious trouble is to be expected in the capital very shortly. I believe it necessary to have Paris occupied by the French and Allied forces as soon as possible even if it means a certain amount of fighting and a certain amount of damage within the city.”

General Eisenhower pondered de Gaulle’s letter as well as a cabled message from diplomat Nordling telling of the situation in Paris. Military action was now needed, Eisenhower decided. He scrawled a note across the top of the letter before sending it to his assistant, General Walter Bedell Smith: “It looks now as if we’d be compelled to go into Paris. Bradley and his G-2 think we can and must walk in.”

At the airport in Le Mans, liberated a week earlier, Free French General Jacques Leclerc swung his cane as he paced nervously, awaiting the arrival of U.S. General Omar Bradley, commander of ground forces in the region. With Leclerc was the Resistance chief of staff, Major Gallois. Over the noise of the still running engines of Bradley’s plane, they were told of Eisenhower’s decision: “You win. They’ve decided to send you straight to Paris.”

Standing on the Le Mans airstrip, General Bradley impressed on the two French officers the seriousness of the steps they were taking.

“A grave decision has been made and we three bear the responsibility for it: me, because I am giving the order to take Paris; General Leclerc, because he is the one who has to carry out this order; and you, Major Gallois, because it is based on the information that you have brought that we have acted.”

The order from General Eisenhower had come just in time to prevent an irreparable split in the Allied front. General de Gaulle, irritated and frustrated by what he considered to be further stalling, had already given Leclerc the order to launch a reconnaissance column toward Paris. The road to Paris was now open to whoever dared take it.

Within a few hours of receiving the green light to move on Paris, Leclerc assembled his 2nd Armored Division and was giving final instructions to his officers. By now, the division consisted of 16,000 battle-hardened men, 200 U.S. Sherman tanks, 4,000 cars and armored vehicles, and more than 600 artillery pieces. It would jump off at dawn on Wednesday, August 23, with three columns taking separate routes on the 240-kilometer track eastward to the capital. The largest column, under Colonel Pierre Billotte, was to throw every ounce of its strength along an arc aiming at Fresnes, site of an infamous prison 20 kilometers from the capital. That would put Billotte in a position to slam into the city via Versailles and the Porte d’Orléans, the old southern gateway to Paris.

General de Gaulle by now had reached Chateau Rambouillet, the old country home of French presidents 50 kilometers southwest of Paris. Soldiers of General Leclerc’s command were camped among the rain-soaked bushes surrounding Rambouillet. Seated in the Chateau’s ornate Salle des Fêtes, de Gaulle and two senior officers dined on cold, canned American C rations. After dinner, de Gaulle had Leclerc ushered into the room. Leclerc outlined his battle plans for the next day, pointing out the routes for each of his three columns.

De Gaulle pondered the report of his young commander and, after a brief moment, nodded his assent. The general stood and held out his hand. They shook. “How lucky you are,” de Gaulle said. Then, apparently with thoughts of the bloody aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 in mind, he added, “Go quickly. We cannot afford another Commune.” That night, de Gaulle relaxed with a book from the chateau’s library.

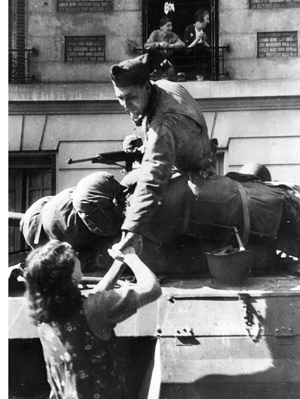

At 6 o’clock Thursday morning, Leclerc’s three columns were on the move along a front 30 kilometers wide. German troops put up strong resistance around the town of Trappes, and the advance went slowly as delirious crowds embraced their French liberators, offering kisses and wine. The day-long procession led General Bradley to complain that the French were “dancing their way into Paris.” He ordered the dispatch of the U.S. 4th Infantry Division into Paris, ensuring the French would not be alone in the liberation of their capital. When word came that the temporary truce in Paris had been broken by Communist units, Leclerc decided to send an advance detachment into the city.

At a crossroads near Trappes, Leclerc encountered Captain Raymond Dronne, a veteran of the African battles in which the Free French had cleared France’s central African colonies of Nazi sympathizers and had gone on to help U.S. forces oust German armies from Tunisia.

“Dronne, what the f— are you doing here,” Leclerc demanded to know. Dronne explained that his company of tanks and armored cars had been commanded to return to reserves. “Never carry out an idiotic order,’ Leclerc answered. “Get on into Paris immediately,” he added.

“Is my objective to be the heart of Paris?” Dronne asked.

“That’s right, Paris. Tell the Resistance not to lose heart, that tomorrow morning the entire division will be there.”

Dodging German formations, Dronne’s three tanks and a dozen armored cars entered Paris through the Porte d’Italie. There was no serious resistance, and once in the city the column was engulfed by crowds blocking their way. “Les Americains!” someone shouted. “Ce sont des Français,” an even more excited voice called out. German sharpshooters fired at the column as it passed the Gare d’Austerlitz, but Dronne moved his men on quickly without returning the shots. Once across the Seine River, the column had unimpeded access to the Hotel de Ville (city hall) of Paris. The clock showed 9:22 pmwhen Dronne’s jeep parked in the square. He and his men were surrounded by Resistance forces that had taken over the building. One after another, the churches of Paris began to ring their bells, with the great 14-ton bell of Notre Dame Cathedral the last to join the chorus.

While Paris slept uneasily, forward units of General Leclerc’s 2nd Armored Division spent the night probing the outer ring of the German defenses. Warnings had come from the Resistance of enemy troop concentrations, some supported by German armored units. Shortly after midnight, an advance detachment that had secured the Pont de Sevres on the Seine made its way across the bridge. They could hear sounds of German soldiers advancing toward them. German machine guns set up along the road began firing, and in a half hour battle the Germans lost three armored cars and three guns before retreating. French officer Jacques Massu estimated they had killed 40 to 50 Germans and taken a dozen wounded men prisoner. For the rest of the night, French patrols fanned out from the site of the battle, alert to any return of the enemy.

At dawn on Friday, August 25, French and American units fought their way into Paris, picking off scant resistance from 15,000 German defenders. Parisians surged into the streets to welcome their liberators. At 6 am, as Simone de Beauvoir would later write, she ran along the Boulevard Raspail to see “the Leclerc division parade on the Avenue d’Orléans and along the sidewalk, an immense crowd applauded. From time to time a shot was fired; a sniper on the roofs, someone fell, was carried off, but no one seemed upset: enthusiasm stamped out fear.”

While troops of the U.S. Fourth Division camped at the Bois de Vincennes and took control of eastern Paris, the first soldiers of the Free French 2nd Armored reached German headquarters at the Hotel Meurice around 2 pm. Lieutenant Henri Karcher, anxious to reconnect with his Parisian family, rushed the front door with three of his men. Smashing it open, Karcher spotted a large picture of Adolf Hitler hanging in the lobby. He turned his machine gun on it, ducked behind the reception desk, and threw a grenade in the direction of a German soldier who was firing at him from behind a pile of sandbags. The German fell dead, his helmet clattering to the floor.

Karcher bounded up the stairs to the first floor, where he confronted a German who quietly agreed to take him to General Choltitz. Asked if he was ready to surrender, Choltitz replied, “I am.” He was spirited to the Prefecture of Police, where he signed the surrender order. It was in the name of the Provisional Government of the French Republic. Just as General Leclerc was about to sign the document, the Communist leader of the Resistance, Colonel Rol-Tanguy, burst into the room. He was furious he had not been invited to the ceremony and demanded that he be allowed to sign the surrender agreement.

From the Prefecture, Choltitz was driven to Gare Montparnasse to await the arrival of General de Gaulle. De Gaulle arrived at 4 pmand was taken to Platform No. 3, where General Leclerc, his uniform now sweat stained, welcomed him. When de Gaulle was shown the surrender document, however, he berated Leclerc for having permitted Rol-Tanguy to sign it. “This is not exactly right,” he told him.

The ceremony completed, de Gaulle was driven through sniper fire to his old War Ministry office, where he found “not a piece of furniture, not a rug, not a curtain had been disturbed.” Then it was on to l’Hotel de Ville, where the leaders of the Resistance awaited him. A tumultuous roar filled the building as de Gaulle made his way to the foot of the grand staircase leading to the great salon on the first floor.

Once in the hall, people surged around him. Everyone began talking at once. De Gaulle had not prepared a speech, and he had no podium from which to address the crowd. Bareheaded, his gesturing hands keeping time with his words, de Gaulle uttered his memorable line of defiance: “Paris outraged! Paris broken! Paris martyred! But Paris liberated!” The next day Free French forces paraded down the Champs Elysees, hailed by a million Parisians. A week later de Gaulle ordered men of the Resistance into the army and set out to form a provisional government. His arrival had come in time to thwart Communist plans to set up a new Paris Commune and before the Germans could begin destruction of the city. The race to liberate Paris had been won.

Ray Argyle is a Canadian journalist and author of several books, including The Paris Game: Charles de Gaulle, the Liberation of Paris, and The Gamble That Won France. During his long association with France, he has closely tracked the political careers of Charles de Gaulle and his successors. He is working on a book on Vincent van Gogh’s years in France.

Certainly De Gaulle was a rather disagreeable person but he recognized, when Roosevelt seemingly did not, a post war Communist threat. Same goes for Italy who had similar plans for a post war government. Few realized until much later how close both of these countries came to being Russian satellites.

fdr was mighty chummy with uncle joe. fdr definately had socialistic leanings as we can see even before the war. uncle joe played fdr and churchswill like a fiddle.