By Robert F. McEniry, Lt. Col. USAF (ret.)

General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Allied Commander Southwest Pacific Area, kept his promise to return to the Philippine Islands when his Sixth Army under the command of Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger landed at Leyte in October 1944.

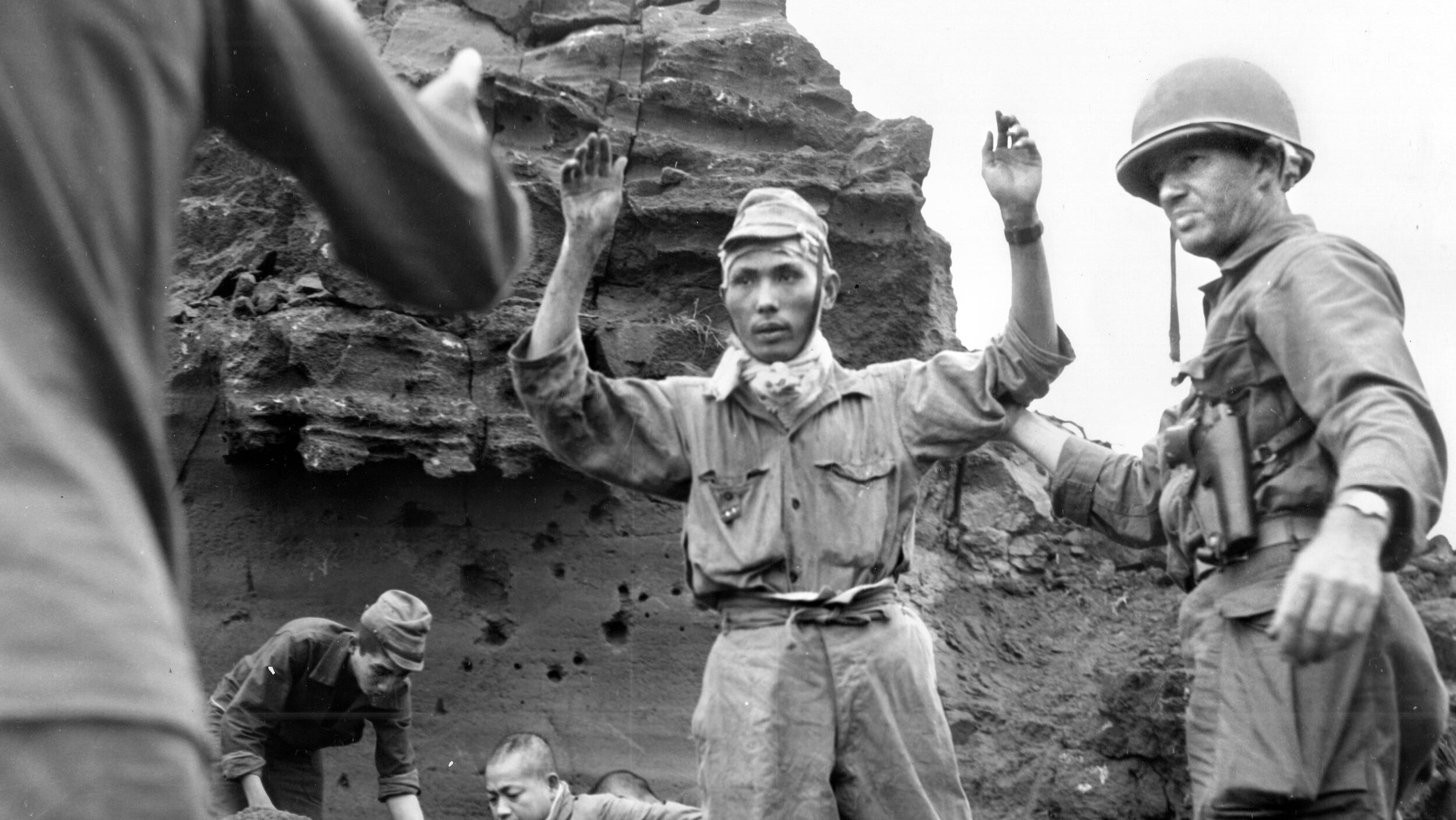

The Imperial Japanese response was swift. In the largest naval actions of the Pacific War the Imperial Japanese Navy fought and lost a series of bruising naval battles to Admiral William F. Halsey’s Third Fleet and Admiral Thomas Kinkaid’s Seventh Fleet in the Battle of Leyte Gulf during the same month. Even though the Imperial Japanese Navy had been thoroughly defeated, the Imperial General Headquarters still had over 410,000 soldiers in the Philippines under the command of General Tomoyuki Yamashita in the Japanese 14th Area Army and General Shigeyaku Suzuki’s 35th Area Army.

The Japanese also had considerable airpower in the Philippines with the 4th Air Army under Lt. Gen. Kyoji Tominga, the Imperial Japanese Navy 2nd Air Fleet under the command of Vice Admiral Shigeru Fukudome, and the 1st Air Fleet under Vice Admiral Takajiro Onishi. These Japanese air forces were primarily stationed on Luzon at the Clark Air Field complex and launched relentless conventional and kamikaze attacks on the U.S. Third and Seventh Fleets.

From October to the end of 1944, a total of 79 U.S. Navy warships, merchantmen, and amphibious vessels were sunk or damaged by land-based conventional and kamikaze attacks. Among the damaged warships were the aircraft carriers Intrepid, Franklin, Belleau Wood, Cabot, and Essex. The light carrier Princeton was sunk by a conventional land-based Japanese bomber attack.

Clark Field: A Crucial Japanese Airbase in the Philippines

General MacArthur ordered Fifth Air Force commander Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney to launch major land-based air raids against Luzon as soon as his planes were established on Leyte. The stage was being set for one of the largest medium- and light-bomber attacks of the Pacific War.

The target for the attack was Clark Field, operated by the Japanese since their conquest of the Philippines in 1942. The Japanese Navy units known to have been at Clark consisted of the 261st, 761st, 762nd, 752nd, and 901st Kokutai equipped with Mitsubishi G4M Betty bombers, and the 201st Kokutai equipped with Mitsubishi A6M5 Zero fighters.

Known Japanese 4th Air Army units at Clark included the 60th Sentai equipped with Kawasaki Ki-21 Sally bombers, the 208th Sentai equipped with Kawasaki Ki-48 Lilly bombers, the 26th Sentai equipped with Kawasaki Ki-43 Oscar fighters, the 13th Sentai equipped with Kawasaki Ki-45 Nick fighters, the 19th Sentai Equipped with Kawasaki Ki-61 Tony fighters, the 22nd Sentai equipped with Kawasaki Ki-44 Tojo fighter, the 62nd Sentai equipped with Kawasaki Ki-49 Helen bombers, and the 15th Sentai equipped with Kawasaki Ki-46 Dinah reconnaissance aircraft.

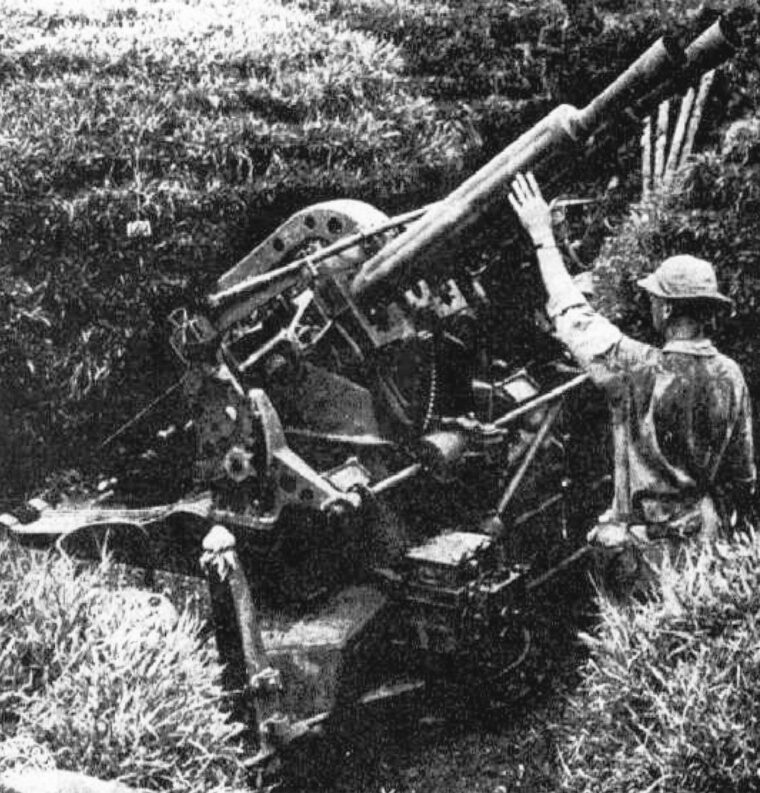

Clark airbase facilities consisted of six airstrips, Clark runways 1-6, and the five runways at Angeles City adjacent to Clark airbase. The antiaircraft defenses surrounding Clark were some of the most formidable in the Pacific Theater and as potentially hazardous as any heavily defended target in the European Theater. The Japanese defenses included 74 heavy antiaircraft guns of the 75mm Model 88, 237 medium guns of mixed types including Model 96 dual and triple 25mm, Type 40 40mm, Model 98 20mm, and Model 93 13mm twinbarreled AA weapons. The 174 light guns were dominated by Model 92 7.7mm machine guns.

These 485 guns were dispersed around the complex and manned by over 1,200 Japanese Army and Navy gunners. The Japanese also used combat air patrols of fighters to defend the airfields. In addition, 16 Japanese Army and Navy ground radars were present and still active with the potential of providing advanced warning to the Japanese defenders.

The Japanese also used ground-based visual observers to provide information on Allied aircraft passing nearby. They dispersed and heavily camouflaged their aircraft and constructed decoy aircraft and gun positions to protect their vital resources from air attack.

The Plan of Attack

The Fifth Air Force moved bomber and fighter units to Leyte and Mindoro as soon as their bases were ready for operations. Aircraft from Tanauan and Tacloban airfields on Leyte and San Jose airfield on Mindoro were slated to launch airstrikes against Clark, beginning on January 7, 1945.

The actual planning for the first mission was accomplished by the staff of the 310th Bomb Wing. From Tanauan airfield 48 Douglas A-20G Havoc aircraft of the 312th Bomb Group, commanded by Colonel Robert Strauss, would take off. The 312th was represented by 12 aircraft each from the 386th, 387th, 388th, and 389th Squadrons. The 312th had unique unit markings, each bomber emblazoned with a skull and crossbones on the nose, through which the machine guns fired.

From Tacloban, 40 North American B-25J-11 aircraft of the 345th Bomb Group, commanded by Colonel Chester Coltharp, would join the 312th. The 345th squadrons represented in the raid included the 498th, 499th, 500th, and 501st with 10 aircraft each. Coltharp was the strike leader for the mission. The 345th also had colorful aircraft markings. Known as the Air Apaches, their planes had an American Indian chief logo on the rudders. In addition, various aircraft had bat’s head images or hawk’s head images painted on the noses with additional personal markings.

The combined formation would fly northwest over the Visayan Sea until they were off the southwest coast of Mindoro, where 48 A-20G aircraft of the 417th Bomb Group, commanded by Lt. Col. Milton W. Johnson and consisting of 12 aircraft each from the 672nd, 673rd, 674th, and 675th Squadrons, would join the effort. The formation would be escorted by 24 Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters of the 8th Fighter Group, which would depart from San Jose and join up with the formation.

The formation would split into two waves on the run into the target. The first wave would consist of 24 A-20Gs of the 312th Bomb Group’s 388th and 389th Squadrons and all 40 B-25J aircraft of the 345th Bomb Group. The 312th aircraft were on the right side of the first wave formation with the 345th to their left. The second wave would consist of 24 A-20G aircraft of the 312th, 386th, and 387th Squadrons and the 48 A-20Gs of the 417th Bomb Group. The 312th was also on the right side of this formation with the 417th on the left.

The first wave would attack Clark flying northwest to southeast. The second attack wave would fly from northeast to southwest. The two waves would create a large X pattern over the target. The mission planners’ hope was that this would help the attackers locate and destroy all the dispersed and camouflaged aircraft hidden close to the airstrips.

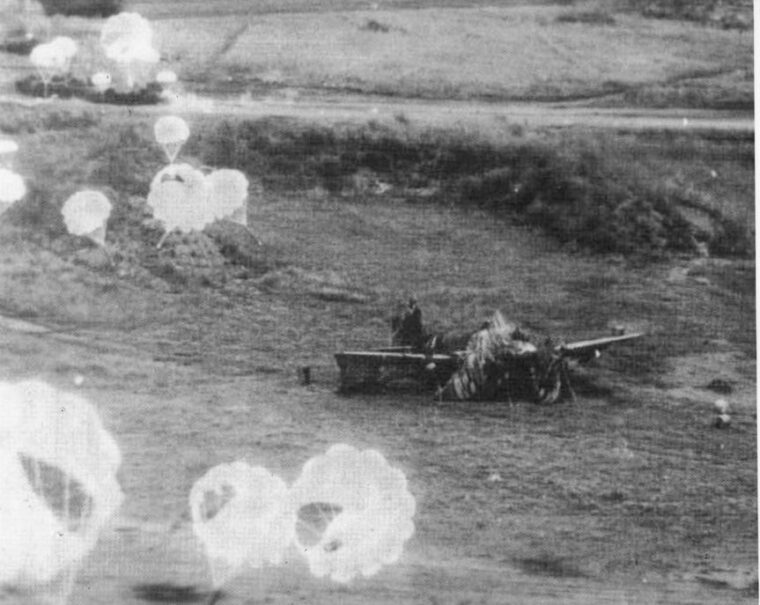

23-Pound Parafrags

The primary weapons for the mission would be thousands of 23-pound AM 40 parachute fragmentation bombs, otherwise known as parafrags. The mission planners also hoped that by flying up the west coast of Luzon the attackers would reduce the potential for detection from Japanese radar sites and confuse Japanese ground observers as to the mission’s true target. With three bomb groups attacking Clark from the north, it was hoped that an element of surprise could be achieved, catching the Japanese antiaircraft gunners flat-footed, reducing losses. Radio silence was to be maintained to prevent detection by Japanese listening posts.

Each of the three bomb groups came to the raid with different motivations. The 345th Bomb Group had lost over 200 dead, wounded, and missing ground personnel in a kamikaze attack on the Liberty Ship SS Thomas Nelson and lost an additional 22 dead and 40 wounded in a second kamikaze attack on the Liberty Ship SS Morrison R. Waite on November 12, 1944. The 417th Bomb Group had endured frequent air attack and had lost a number of aircraft on the ground. The unit also had lost its popular commander, Colonel Howard S. Ellmore, killed when his A-20G struck the superstructure of a Japanese merchant ship and crashed during a low-level attack on January 2, 1945. The January 7 raid would be the first group-size raid led by Ellmore’s replacement, Lt. Col. Johnson.

The 312th Bomb Group was the most recent of the three to arrive in the Philippines. An experienced group, the 312th’s flying element had just arrived days before this planned raid, eager to get in the fight.

Challenges of the Raid

The Japanese were not idle during this period. They were desperately trying to find ways to get aerial reinforcements to the Luzon bases and were to trying figure out ways to strike back at the growing American airpower in the region. Despite heroic efforts and ghastly sacrifices, nothing seemed to be slowing down the American airpower buildup despite the losses the Japanese inflicted. The Japanese knew that if land-based American airpower built up enough, Japanese air operations would be finished in the Philippines.

All the American aircrews were briefed on the mission on the night of January 6. The ground crews spent most of the night ensuring that the bombers were ready for the morning’s important mission. The aircrews were awakened at 4 am for breakfast and preflight checks. The 312th Bomb Group’s A-20Gs took off at 6:50 am into a bright, clear sky over Leyte. During the takeoff a 388th Squadron A-20G piloted by 2nd Lt. Eugene M. Bussard with gunner Sergeant Harvey Walker made one turn from Tanauan and crashed into the bay. Both airmen were killed. The cause of the crash was never determined but was presumed to be some type of mechanical failure.

Meanwhile, the 345th Bomb Group’s 40 B-25Js took off from Tacloban at the same time. Both groups joined up and set course northwest at 1,500 feet, cruising speed 200 miles per hour. This would be a long mission, over 1,000 miles round trip with an estimated 61/2 hours of flight time for these two groups.

The 48 A-20Gs of the 417th Bomb Group and the 24 P-38 escorts of the 8th Fighter Group joined the formation above Mindoro. The formation followed the west coast of Luzon, staying over the ocean and taking care to stay well clear of the U.S. Navy Lingayen Gulf invasion fleet to avoid friendly fire.

Suddenly, two Japanese single-engine fighters came out of the haze with a P-38 in hot pursuit and made a beeline for the invasion fleet. An enormous antiaircraft barrage erupted at the two Japanese planes. The fire was of no direct threat to the formation, but the aircrews did feel the concussions of some of the larger detonations. The fate of the Japanese planes was not known.

The formation flew north of Manila and Subic Bay. Forty miles north of Subic Bay, it turned east and broke into the two attack groups. Unfortunately, the weather started to deteriorate. A layer of low clouds had descended over the hilltops. This forced some of the flights to jockey for position. Some chose to follow the formation below the low clouds into the pass. Other flights, due to the narrowness of the pass below the cloud cover, decided to climb through the clouds, clear the hills, and drop back down to rejoin the formation. Thus, the cloud cover broke up the formation.

Another problem with the planned in-line formation was that the A-20G and B-25J aircraft had different attack speeds and flight characteristics. The A-20Gs had a difficult time making the turn and staying in formation without stalling out. This caused some of the 312th A-20Gs to break formation to maintain flight speed.

First Wave of Attack

The mandatory radio silence also meant that pilots from the different groups could not communicate what they were doing. All of these changes in formation almost had tragic results during the attack. As this jockeying for position was going on, one of the A-20Gs from the 389th Bomb Squadron started to lag behind the formation, streaming smoke from the right engine. Because of the radio silence, no one in the formation new what the status of the aircraft was. The aircraft, Sleepy Time Gal being flown by 2nd Lt. Harry Lillard with his gunner Corporal Henry F. Lutage, crashed in the target area, and both men were killed.

Once through the clouds and into the valley, the first wave made its turn to the southeast and accelerated to the attack speed of 250-275 miles per hour. The first wave was a loose gaggle of 64 aircraft jockeying for position. The worst aspect of this was some aircraft of the 389th Bomb Squadron found themselves out of formation on the left side, in front of aircraft from the 345th Bomb Group.

The B-25Js were forced to fly through some of the parafrag bombs released by the A-20s, and the B-25s had to be careful not to shoot down the A-20s that had inadvertently flown in front of them. The A-20s soon realized their mistake as B-25 machine-gun fire erupted all around them. Amazingly, no B-25s were hit by parafrags from the A-20s and no A-20s were hit by B-25 machine-gun fire, but it had been a close call.

Bomber pilots saw camouflaged Japanese aircraft and made straight for them, dropping parafrags and machine gunning any target that looked worthwhile. First Lieutenant Joseph Rutter of the 389th Squadron noted, “As we ran toward the trees and the ruined hangars beyond I worked the rudder pedals and strafed every likely target. There was no shortage of planes, trucks, or buildings. I could see planes everywhere I looked—fat Bettys, hump-backed Tonys, delicate Oscars, twin-engine and single-engine, some in the open and others in revetments, most with camouflage netting over them. It was beautiful! What a field day!”

The Japanese gunners were at first caught off guard, with some of their guns even under cover. First Lieutenant Tom Jones of the 389th Squadron flying in an aircraft named Little Joe in the first wave noted, “Enemy aircraft circling above us were dropping phosphorous bombs in the midst of the formation. We raced across the target, made our right turn and headed down the Bataan peninsula for Manila Bay.”

The Japanese soon recovered as the first wave passed over the target, and the volume of antiaircraft fire quickly reached a crescendo. A 345th B-25, the Sag Harbor Express piloted by 2nd Lt. Arthur Browngardt, Jr., was hit by antiaircraft fire in the right engine. The crippled aircraft flew over the airfield, over the town of Angeles, clipped a church steeple, crashed, and exploded in flames. All six crewman aboard were killed on impact.

Another 345th B-25 from the 500th Squadron, piloted by 1st Lt. Howard D. Thompson, had its right side raked by antiaircraft fire. The tail gunner, Staff Sergeant John Regin, was wounded by shell fragments. The crippled B-25 was able to make a wheels up crash landing at Mindoro with the entire crew surviving.

As the first wave of 345th and 312th bombers strafed and bombed, they were attacked by six or seven Japanese Zero fighters dropping parachute phosphorous bombs while orbiting at 1,500 feet over the formation. No American bombers were struck. As the 501st Squadron departed the target area and just a few miles north of Subic Bay, a lone Ki-43 Oscar fighter made a tentative pass at the squadron. Alert B-25 gunners fired a few bursts, which deterred that pilot from further attacks.

Seconds after the Oscar, another fighter flew over the formation and dropped a phosphorous bomb that caused no damage. The first wave had damaged or destroyed several dozen bombers and fighters. Two aircraft were lost. Over half the first wave planes, 35 aircraft, received flak or small arms damage. Several aircraft made emergency landings on Mindoro rather than trying to fly all the way back to Leyte.

Second Wave Meets Heavy Resistance

The enemy defenses were thoroughly alerted and gave the second wave a hot reception.

The second wave took the full brunt of the Japanese fire. A plane from the 386th Bomb Squadron piloted by Captain Frank C. Hogan was struck by antiaircraft fire over the Macalabat East airfield and set ablaze. Hogan made a successful crash landing outside Clark Field in a rice paddy near the town of Magalong. Friendly Filipino guerrillas rescued Hogan and his gunner, Staff Sergeant Joseph Joyce. Joyce had suffered severe head injuries and had one of his legs severed in the crash. He died 15 minutes after being recovered by the guerrillas. The Filipino guerrillas eventually got Hogan back to U.S. forces after several weeks.

Another passenger aboard the A-20, 1st Lt. Isaac Lobell, the 312th Group photographer, died when he was forced to parachute at insufficient altitude. He died when he struck the ground. Another 386th Squadron bomber was also struck by fire. This plane, piloted by 2nd Lt. Rupert Perry, flew all the way back to Leyte but crashed into Leyte Gulf while trying to make the airfield. The gunner was rescued, but the pilot did not survive. A third 386th bomber had an engine shot out. This plane, piloted by 2nd Lt. Ormande Frison, made a successful crash landing at Tanauan airfield, saving himself and his gunner, Sergeant Alex Wasserman.

The 417th Bomb Group did not have an easy time in the second wave. While flying down the middle of one of the Japanese runways, a thunderous explosion rent the ground and the air. In a second, three aircraft from the 673rd Squadron crashed and were destroyed. One of the three A-20Gs to crash was piloted by 1st Lt. Rodney D. Beckel. His gunner was Staff Sergeant Francis L. Malone. After U.S. forces captured Clark, it was determined that the Japanese defenders had buried 110-pound aerial bombs under the runway and electronically detonated them from a gun position when the aircraft flew over. This was the first time in the Pacific Theater that this tactic had been encountered.

Finally, a fourth A-20 was shot down by ground fire over the target. There were no survivors from any of the 417th bombers that were lost. As the second wave departed, seven of its aircraft had crashed over the target before returning to base.

Breaking the Back of the Japanese Air Force

The results of the raid were considered successful. A total of 7,836 parafrag bombs and over 100,000 rounds of .50-caliber machine gun ammunition were expended on targets at the six airstrips and surrounding dispersed aircraft. Intelligence verified that dozens of fighters and bombers were destroyed and that scores more were probably destroyed or damaged.

Japanese suicide missions dropped off appreciably after January 7, and the U.S. Navy Lingayen Gulf invasion force received only sporadic attacks. The raid unquestionably saved hundreds, possibly thousands, of American lives.

On January 8, 1945, the day after the raid, Lt. Gen. Tominga took his remaining ground and support personnel and formed them into the Kenbu Composite Infantry Division. These former airmen would now fight as infantry since their aircraft and airfields now lay in ruins.

Vice Admiral Fukudome fled to Singapore by flying boat on January 15. Vice Admiral Onishi took his remaining 30 flyable aircraft, retreated to the town of Aparri in extreme northern Luzon, and ordered all the planes back to Formosa in mid-January.

The total cost to achieve this major success had been one aircraft destroyed and one seriously damaged in the 345th Bomb Group with six killed and three wounded. The 312th Bomb Group lost a total of five aircraft destroyed with seven killed and two wounded. The 417th Bomb Group lost four aircraft, eight killed, and three wounded. More than 65 aircraft from all the groups received some type of battle damage.

Considering the extent of the defenses and the results achieved, the losses were considered acceptable. General Kenney ordered a single mission Air Medal awarded to all participants. It was the January 7, 1945, raid that finally broke the back of Japanese airpower in the Philippines.

Does anyone know whether my uncle, 1st Lt. Willard C. Mogg, participated in this battle?