By David H. Lippman

The Germans could not believe it. Without suffering the loss of a single soldier or sailor, the German Army and Navy had sailed 1,500 miles through waters dominated by the British Royal Navy and captured Narvik without firing a shot, bagged nearly 500 Norwegian soldiers, seized one of Norway’s major military depots, and even taken five armed British merchant ships and their crews. The victory was virtually complete. Now all the German destroyers and the tough men of General Edouard Dietl’s mountain troops were taking on fuel, ready to return to Germany and prepare for new victories.

Instead, the Germans were about to face their first large-scale naval action since Jutland, and a massive defeat. Norway in general and Narvik in particular had been central to Allied and German strategic planning since the outbreak of war. The all-weather port was the route by which Germany received vast supplies of Swedish iron ore. The British wanted to shut down the route in order to cripple Germany’s economy, while the Germans needed to secure it.

At the same time, the German Navy, despite its small size, had great dreams. Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, who commanded the Kriegsmarine, saw in Norway’s vast coastline an opportunity to provide his ships with bases on the Atlantic and to prevent the British from repeating the deadly blockade of 1914-1918. The fact that Norway was an ardent neutral meant little to the great powers and their plans.

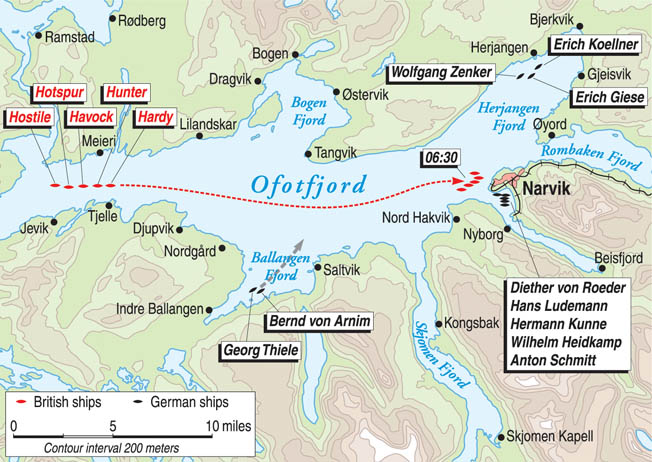

Both sides planned to violate Norway’s neutrality, the British by mining her waters and then landing troops at Narvik to cut the rail and sea line, the Germans by landing troops at key ports the length of Norway. The British laid their mines first. The Germans landed their troops at Norway’s ports first. The farthest one was Narvik, the target for the 139th Mountain Infantry and the 10 destroyers of Commodore Erich Bonte’s Task Group 1, organized into three flotillas.

The Defenses of Narvik

The German destroyers were modern vessels, all launched between 1935 and 1938, well equipped with five 5-inch guns, four 37mm antiaircraft guns, and eight 21-inch torpedo tubes. They could crack the waves at 38 knots.

The ground troops jammed on the destroyers came from the 139th Mountain Regiment of the 3rd Mountain Division, a tough force of 2,000 Austrians.

The German plan to take Narvik depended on force and guile. The Germans believed from the Norwegian traitor Vidkun Quisling that the Norwegians were ready to surrender and that the defenders were reportedly pro-German.

Narvik itself was a tough cookie to seize. The port lay at the base of the lengthy Ofotfjord, surrounded by craggy Norwegian mountains and conifers.

The war started at Narvik in the early morning hours of April 9, 1940, with the destroyers steaming up Vestfjord in a northwest gale under total darkness and relying on dead reckoning, a tough navigational feat. Weather conditions improved as the tin cans reached the Lofoten Islands. Task Force 1 entered Ofotfjord at 3:10 am on April 9. Dawn was breaking. A Norwegian patrol vessel reported foreign warships entering the fjord.

Norway’s primary naval defenses—two ancient coast defense warships named Norge and Eidsvold, both 40-year-old tubs armed with 8.3-inch guns—prepared to sail. But the Germans moved faster than the Norwegians, their ships fanning out through the fjord, unloading detachments of German troops at machine-gun nests and coastal batteries and seizing them before the surprised defenders could open fire.

Taking Narvik

While the mountain troops grabbed Norwegian positions, three destroyers of Bonte’s 1st Flotilla streaked in on Narvik and the two coast defense ships themselves. As they neared the harbor entrance at 4:15 am, the Eidsvold popped out of a snow squall and challenged the invaders. Bonte tried to negotiate his way past, sending over an officer to the Norwegian ship to tell them the Germans had come as friends to defend Norwegian neutrality against the British. The Norwegians were unimpressed and told the Germans they had orders to fire on the German destroyers. The German officer returned to his ship, and the Eidsvold squared off against the destroyer Wilhelm Heidkamp, flagship of the German force.

The German orders were to fire only if fired upon by the Norwegians, but the Eidsvold had more powerful guns than the Heidkamp. Bonte chose not to wait and fired four torpedoes at the oncoming Norwegian, which hit along her port side and set off the ammunition magazines. The explosion blasted the ship into two pieces. It sank within 15 seconds, and only six men of its crew of 181 were saved. Three swam to safety, while the others were picked up by the Germans.

With one coast defense vessel down, the other one was next. The Norge’s skipper was not sure if the two oncoming destroyers were British or German, so he held his fire for a few minutes. The Germans sailed straight for the Steamship Pier to unload troops, and Norge opened fire. The two German destroyers hit back with torpedoes. The first five missed, but the last two hit, one aft and one amidships. Norge capsized to starboard and sank with the bottom up in less than a minute. Out of 191 aboard, some 101 went down with the ship. Ninety men were saved, including Captain Per Askim, who was hauled unconscious out of the drink.

With its two largest ships sunk, 276 dead, and having accomplished nothing, there was little left the Norwegian Navy could do against the invaders. The Germans swiftly captured the surviving patrol boats, and one of the submarines based at Narvik was scuttled while the other two fled to sea. Its defenses disorganized and overawed, Narvik fell swiftly to the invading German troops. General Dietl, commander of the 3rd Mountain Division, impressed the Norwegian commander with the large force he had at his disposal, and the Germans came ashore.

Low on Fuel

The Germans were very pleased with themselves as April 9 wore on. However, the celebration did not last long. Dietl had to consolidate his positions, and the German destroyers had to refuel and return to Germany. And there was the first problem. The German tin cans were dependent on two large tankers that were supposed to be in Narvik ahead of the invaders, deployed in a “Trojan Horse” maneuver.

But while the tanker Jan Wellem had made it, the Kattegat did not, stopped south of Bodo by the British minefield, intercepted by the Norwegian patrol boat Nordkapp, and sunk in shallow water. The Norwegians salvaged most of her cargo.

Now Bonte required 600 tons of fuel for each destroyer to make the voyage home to the Fatherland, and he had only half the fuel the operational plan called for. He could mix diesel fuel with boiler oil to fill his tanks, but with only one tanker present, it would take twice as long to fill his ships’ bunkers. With one tanker, only two destroyers could refuel simultaneously, and each pair required seven to eight hours. Only three destroyers were refueled by midnight on April 9.

Bonte radioed his plight to his chain of command, saying he could not leave Narvik on the 9th as planned but would have to do so on the 10th. In the interim, he scattered his ships around the fjord to lessen the danger of aerial attack. The Germans deployed U-boats off Ofotfjord as a picket against British naval attack. They reported four British destroyers on a southwest course—away from Narvik.

Warburton-Lee: A “Man of Integrity, Honor and Ambition”

The four destroyers heading southwest were the 2nd Destroyer Flotilla, commanded by Captain Bernard Armitage Warburton-Lee, and they had orders to go to Narvik to ensure that no German troops landed in that city. They were heading southwest to await high tide and an opportunity to steam into the fjord.

Warburton-Lee was described by a British historian as a “man of integrity, honor and ambition; a dedicated man, intensely professional and although an excellent games-player somewhat aloof and single-minded.” He led four destroyers, Hardy, Hunter, Havock, and Hotspur, and was joined by a fifth, HMS Hostile.

Warburton-Lee was skeptical about the information forwarded by the Admiralty that the Germans had seized Narvik with only one ship and did not believe the Germans would use only a few troops to take the port. Operating without much intelligence, he sailed to Tranoy Lighthouse on the east side of Vestfjord at about 4 pm, to ask the Norwegians if they knew what was going on.

The British went ashore and did not speak Norwegian. The Norwegians spoke no English. Through sign language and a few words of English, they determined that at least six German destroyers had sailed into Narvik along with a submarine.

Warburton-Lee was now outnumbered, and there was a strong possibility the Germans had mined the narrows behind them. With the odds against him, Warburton-Lee could be justified in waiting for the battlecruiser Renown and her 15-inch guns. But he also had orders to act aggressively, and the Royal Navy had a tradition of victory and acting aggressively in the face of larger numbers.

For 30 minutes, Warburton-Lee agonized over what to do. He finally chose aggressive action, deciding to attack at “dawn high water.” A dawn attack at high tide would get him over the reported minefields (there were none) and gain maximum surprise.

The proposed attack was risky in the extreme—the German destroyers outnumbered the British and were better armed. But the British had to take action.

“We Shall Support Whatever Decision You Make”

Meanwhile, the Germans were enjoying a false sense of security. With Narvik in hand and no counterattack materializing on April 9, Bonte hit the sack before midnight. One of his last moves was to assign the destroyer Anton Schmitt to patrol the harbor entrance, with visibility only a few hundred feet in a continuous snowstorm.

Bonte was not the only one who was exhausted. The destroyer crews had been at action stations for 48 hours. Even the successful seizure of Narvik did not give them a break as the crews had to switch from action stations to fueling stations for the rest of the day.

At 4 am, Anton Schmitt was relieved of its patrol duty by the Diether von Roeder, under Lt. Cmdr. Erich Holtorf.

Meanwhile, the 2nd British Destroyer Flotilla proceeded up Vestfjord at 20 knots, everyone nervous. Visibility was nearly zero in the snowstorms, which prevented them from being spotted by German U-boats, but making it tough to spot rocks and shoreline. The British ships were forced to break radio silence and transmit navigational messages in the clear. Incredibly, the Germans were not scanning British frequencies for enemy tactical information.

At 1:36 am, the Admiralty radioed Warburton-Lee, “Norwegian defense ships Eidsvold and Norge may be in German hands. You alone can judge whether in these circumstances attack should be made. We shall support whatever decision you make.”

At 3:30 am, Diether von Roeder headed for the entrance to Narvik harbor after only 30 minutes on patrol. Holtorf figured this would bring him into the harbor at first light. She was supposed to remain on patrol until 4:20 am, but there seems to have been a misunderstanding of orders.

Either way, at 3:43 am, the lead British ship, Hardy, was one mile from Diether von Roeder. Warburton-Lee signaled his ships, “I am steering for the entrance of Narvik Harbor.” The British were on the same course as the German destroyer.

Attack at Daylight

The first light of dawn broke as land appeared off Hardy’s port bow. It was supposed to be Framnes Peninsula, but it was actually Emmenes, on the other side of the harbor entrance, a three-kilometer error caused by dead-reckoning navigation, but a fortuitous one for the British, as they avoided running into Diether von Roeder and giving the Germans warning of the impending attack.

The British adjusted course and raised speed to 12 knots, but Diether von Roeder entered harbor just moments before the British. In the dawn, the British spotted the collection of merchant shipping jamming Narvik harbor, but saw no sign of the German destroyers.

Warburton-Lee sent Hotspur and Hostile to the northeast to prevent any enemy ships that could be outside the harbor from interfering with the attack and entered the harbor alone on Hardy. He slid past the merchant ships and encountered two German destroyers, Anton Schmitt and Wilhelm Heidkamp, both stationary. Hardy raised her battle ensigns and fired torpedoes at 4:30 am. The first torpedo missed its mark and hit a merchant ship. The second one hit Wilhelm Heidkamp’s aft magazine, blowing off her stern, blasting her three aft guns. Bonte and 81 of her crew died instantly. Heidkamp’s skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Hans Erdmenger, secured his wrecked vessel next to a Swedish transport and began saving the wounded and some of the valuable equipment as the ship smoldered.

Meanwhile, Hardy exited the harbor at high speed, spotting two additional German destroyers refueling alongside Jan Wellem, the Hermann Kunne and Diether von Roeder. Hardy fired three torpedoes at the German destroyers but all missed.

Now Hunter entered the crowded harbor under her skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Lindsay de Villiers. He was less discriminating with his torpedoes, firing them at the same time he opened up with his 4.7-inch guns, targeting the Anton Schmitt.

On the Anton Schmitt, everyone thought the explosions were an air attack, but a shell hit the forward part of the ship, and everyone knew the truth. Bohme tried to leave his cabin when a torpedo from Hunter hit the ship’s forward turbine room. The resulting explosion jammed the cabin door, trapping him inside. The German ships began opening counterfire, and Hunter laid smoke as she exited the harbor.

Breaking the Anton Schmitt in Two

Next to attack was Havock, entering the harbor as Hunter exited. With the Germans now awake, her skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Rafe E. Courage, faced a tougher task. He spotted Hermann Kunne alongside Jan Wellem and opened fire on these two ships with no hits. The Kunne had steam pressure and was able to maneuver away from the tanker, leaving connecting wires and hoses still hanging in midair. There was no time for a proper disconnection.

Courage turned his guns and 21-inch torpedoes on Anton Schmitt and fired three fish at the German warship. The first two hit merchant ships, but the third hit Anton Schmitt in the aft boiler room just after Bohme was able to open the jammed door to his cabin and was on his way to the quarterdeck. The explosion hurled Bohme over the side. A torpedo hit Anton Schmitt amidships, and the destroyer split in two, sinking almost immediately.

Hermann Kunne had managed to back away from her tanker and was 50 meters from Anton Schmitt when the latter took her fatal hit. The blast sent shock waves roaring through the harbor and slamming against the destroyer’s hull, knocking out her engines. As the forward part of Anton Schmitt rolled over, her mast settled on Hermann Kunne’s deck, and the two destroyers were immobilized and entangled for the next 40 minutes.

The attack was sudden in its force and violence, making it hard for participants to record and realize what was going on. But the Germans were resilient and began opening fire with their guns. Commander Courage decided to break off his attack under fire from Hans Ludemann and Diether von Roeder. Havock was not hit, but Hans Ludemann sustained two damaging hits. Shells blasted apart her forward guns and started a fire in the aft part of the ship. The German crew flooded the aft magazine to prevent an explosion. German troops on shore poured rifle and machine-gun fire at the withdrawing British destroyer.

Hotspur, under Commander Herbert F.N. Layman, and Hostile, under Commander J.P. Wright, now joined the battle, and Hostile took on the still anchored Diether von Roeder. Under heavy smoke, the two destroyers traded salvos. Hostile took no hits, but Diether von Roeder suffered two damaging hits. Hunter fired four torpedoes into the harbor and hit two merchant ships, one of them the British Blythmoor.

Abandoning Ship

Narvik harbor was now a mass of swirling flame, blazing ships, and explosions, but the battle was not over. Three German destroyers were still slugging it out with five British tin cans in the snow and smoke.

Hostile tried to maneuver to launch torpedoes at Diether von Roeder, but the battered German fired first. So did Hans Ludemann and Hermann Kunne. The British now steamed to avoid the German torpedoes. Three of the destroyers would have been hit if the German fish had functioned properly, but the Reich was having trouble with its torpedoes at this time of the war and they did not stay at the preset depth.

Facing all five British destroyers, the blazing Diether von Roeder put up a massive fight. Her power supply to the electrically operated windlass was severed, so she could not hoist anchor, making her a stationary target. The British concentrated their gunfire. They set the boiler room ablaze, wrecked the fire control system, and one shell killed eight men and set the forward section ablaze.

British shells whistled home on Diether von Roeder, blasting Gun No. 3, killing six of its crew. Another shell ignited an ammunition locker, and a third blasted open the aft magazine. The crew flooded the magazine, preventing disaster for the moment. The German guns still fired under local control. Despite the barrage of shells and torpedoes, the engine room gang kept power going. Finally, Holtorf dragged his anchor and backed his battered ship toward the Steamship Pier, and there the ship remained with its bow facing the harbor entrance.

Shore-based firefighters showed up to help quell the blaze, but Holtorf saw that his ship was so badly damaged it was pointless to keep the crew aboard. He ordered all unnecessary personnel to abandon ship.

“This is Our Moment to Get Out”

Meanwhile, Warburton-Lee was plotting his next move. With no fire coming from the harbor, he had time to count German losses. He spotted five of the six reported destroyers he believed the Germans had. With 16 torpedoes left, Warburton-Lee figured he had the enemy at his mercy and ordered his ships to finish off the Germans.

The British destroyers regrouped and steamed back into the harbor in a line-ahead formation at 20 knots to avoid enemy torpedoes and circled in a counter-clockwise direction while raking all observed targets in the harbor with their guns. The British ships exited at high speed at 5:30 am.

The British ships headed westward at moderate speed, and Warburton-Lee met with his officers on the bridge to plan the next move. The staff all wanted to make another run into the smoking harbor to finish off the Germans. Warburton-Lee agreed and even ordered landing parties readied. But he did not know the Germans had 10 destroyers in Narvik harbor, not six, and the ships that had been scattered out of harbor were now racing down as fast as their Krupp engines could take them.

Warburton-Lee led his flotilla back into the harbor, past burning and sinking ships. Hermann Kunne and Hans Ludemann greeted the British with gunfire and torpedoes. All the fish missed, but Hostile took the first large-caliber hit by a British ship of the day. Hardy, leading the British ships, turned west to exit Narvik’s harbor.

Incredibly, the tanker Jan Wellem, at the center of the barrage of torpedoes and shells, had escaped damage. Her skipper feared the worst, though, and ordered the ship abandoned. The captain and crew remained aboard until the British prisoners the ship held were lowered safely away.

Now the three German destroyers hiding in Herjangsfjord raced in from the northeast, surprising the withdrawing British ships. Warburton-Lee estimated the enemy force was one cruiser and three destroyers. “This is our moment to get out,” he signaled at 5:51 am. “One cruiser, three destroyers off Narvik. Am withdrawing to westward.”

Warburton-Lee was mistaken about the enemy’s force size, but it was strong enough—three fresh destroyers leaping out of the morning haze, under Commander Erich Bey.

“Keep on Engaging the Enemy”

In an oblique formation, they opened fire shortly after they were sighted, and both sides exchanged broadsides at 7,000 meters with no impact.

Bey, now the senior German naval officer with Bonte killed, did not know what had happened in Narvik, only that Wilhelm Heidkamp was sunk and Bonte killed. But he was determined to fight it out. He signaled the other two unengaged destroyers, Georg Thiele and Bernd von Arnim, to save themselves by breaking out to the west.

The British destroyers raised to maximum speed to flee the fjord, making smoke as they went. The smoke hid them from Bey’s destroyers, but the other two were coming up from the western side of the fjord. As they steamed into view, Warburton-Lee thought they were the British cruisers Sheffield and Penelope sent to support him. When the two Germans were practically on top of him, he realized his error.

Lieutenant Commander Max-Eckhart Wolf, skipper of the Georg Thiele, was an aggressive officer bent on revenge. He crossed the “T” and brought his guns to bear on Hardy, the lead British destroyer. Warburton-Lee was now sandbagged between two destroyers ahead of him and three behind him.

Seeing that his ships were surrounded, Warburton-Lee signaled at 5:55 am, “Keep on engaging the enemy,” which became yet another part of the Royal Navy’s mythology. It was his last signal.

Moments later, Georg Thiele found the range with its fourth salvo. Two shells struck Hardy’s bridge and wheelhouse and other shells wrecked her forward guns. Everyone on the bridge was either killed or wounded. The only one left alive was Paymaster Lieutenant Geoffrey Stanning, and his leg was shattered. Out of control, Hardy was heading toward the rocky shore at 30 knots. Stanning ordered the helmsman to change course, but the wheelhouse was wrecked and nobody was at the helm. The rest of the British line obediently followed their flagship.

Stanning, despite his injuries, clambered down to the ladder to the wheelhouse and found the helm partially destroyed, but it still functioned when he turned what was left of the wheel. He altered course away from the shore and back toward the enemy. He corrected the course and found a seaman who took the wheel while he climbed painfully back to the flag bridge. He saw two German destroyers off his starboard bow firing salvos.

Incredibly, Stanning’s first thought was to ram one of the Germans, but a shell hit his boiler room and billowing clouds of steam rose over Hardy. There was no choice but to beach the battered destroyer to save the crew. The ship slid gently onto the rocky beach at Virek.

Stanning’s heroism saved the bulk of the crew, but 19 sailors including Warburton-Lee died on Hardy, and a dozen more were injured. Warburton-Lee’s heroism did not go unnoticed, though. On June 7, 1940, he was gazetted with Britain’s first Victoria Cross of World War II. Warburton-Lee is buried in Ballangen New Cemetery in Norway.

Cautious Kriegsmarine Doctrine

Meanwhile, the battle raged on. The other four British ships were still sandwiched. Georg Thiele and Bernd von Arnim turned around to stay ahead of the British ships off their starboard bows. The three eastern German destroyers struggled through the smoke unaggressively, battling mist and falling fuel gauges. The three German destroyers of Bey’s flotilla had not had their chance to refuel and were nearly empty.

German tactical doctrine stressed the importance of avoiding decisive combat in favor of preserving the fleet. Facing smoke, low fuel, and a tough enemy, Bey believed he could not catch up with the faster British force as it withdrew, so he pulled back.

That left two German destroyers against four British, now facing the lead ship, Havock. The British and Germans swapped broadsides and smoke shells. A Havock shell smashed into Georg Thiele’s forward boiler, leaving it inoperable. Another started a fire that forced the Germans to flood the aft magazine.

The Germans shot back, hitting Hunter and Hotspur. Blinded by smoke, Commander Courage decided the German shells were coming from his stern and ordered a 180-degree turn. The other British ships did not see this maneuver in the smoke and confusion, but the Germans did.

Racing down the line of his own ships, Courage saw that Hotspur was out of control and Hunter was burning from bow to stern and losing speed. As he reached the rear of the British line and exited the smoke, Courage saw what he thought were four enemy ships coming up fast. He planned to engage them to slow their pursuit but then changed his mind—his two forward guns had both been knocked out.

Courage turned around again and engaged the enemy with his two aft guns, and then flew into the smokescreen.

Closing the Distance

Georg Thiele now stood ahead of the British line. The Germans saw an opportunity to attack the wounded British. Georg Thiele turned to starboard and immediately took several damaging hits. One shell hit a forward gun, killing nine of its crew. Another shell passed through the bottom of the forward funnel and exploded above deck. Another blew up the fire control room. Georg Thiele’s skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Wolf, did not let these hits deter him from closing the British, running the range down to 1,700 meters.

At that time, the British ships Hunter, Hotspur, Hostile, and Havock, in order, were heading west at maximum speed. Georg Thiele opened fire on Hunter and set her aflame. The ship lost power and drifted to a halt.

Next up, 1,000 meters behind, was Hotspur, and she was unable to see through the smoke screens, which also protected her from German shells. Hotspur fired two torpedoes at Georg Thiele but both missed. Two shells from Georg Thiele hit Hotspur.

The German shells wiped out communications and hydraulic steering on Hotspur. The British ship took an uncontrollable turn to starboard and collided with Hunter’s amidships engine room. The two ships were trapped, easy targets for German shellfire. Hostile maneuvered out of the way.

On Hotspur, Lt. Cmdr. Layman left the bridge to reestablish verbal communications. He got his engines reversed, but while he was off the bridge a German shell hit it, killing most of the people present. Hunter righted itself as Hotspur backed away, but only for a moment. Hunter’s one remaining functioning gun was still firing as the British destroyer rolled over and sank.

Georg Thiele was not in much better shape as two of her magazines were flooded and her hull was ablaze. It was time for Wolf to leave the battle to others, and he withdrew.

The only German destroyer left was Bernd von Arnim, which tried to finish off Hotspur. But Layman established a double human chain of communications between the wrecked bridge and engine room. Under local control, Hotspur’s guns maintained fire, inflicting five hits on Bernd von Arnim as she passed to the north and then retired from the action.

That left two British destroyers, Hostile and Havock, heading westward. They saw Hotspur struggling west and steamed back to help their stricken sister.

That move turned the battle again. Bey’s three German destroyers, still hanging back, saw two British destroyers swinging around toward them at high speed. They backed off, enabling the three British destroyers to continue westward to safety.

Bey was satisfied with what his three destroyers had accomplished, and his fuel levels were near zero. He could just get back to Narvik and chose not to fight another stage of an already harsh battle.

Bey’s ships pulled back past the beached Hardy. Incredibly, the marooned destroyer spat defiance at the Germans, firing a shell at Erich Giese. The German sent a torpedo back, but it malfunctioned. The three German destroyers maneuvered to start searching for survivors from the area where Hunter sank, pulling 48 men from the freezing waters. Ten later died from wounds and exposure.

As the British warships cleared the fjord, they ran smack into the German supply ship Rauenfels, which was just entering harbor. Layman was in tactical command, but with his ship’s communications shattered he turned it over to Lt. Cmdr. Wright on Hostile.

The First Battle of Narvik Concludes

The British saw the German supply ship enter harbor and did not know its nationality. The question was answered when Rauenfels ignored signals to stop. Wright ordered two high-explosive shells fired into Rauenfels when she failed to obey the heave-to orders. The German ship started blazing, and the crew abandoned ship. Wright continued to escort the crippled Hotspur out of the fjord, while Courage in Havock disposed of the German ship.

Courage initially sent over a boarding party, but they decided to leave because of the danger of an explosion. The Germans actually had no idea the British had stopped; they missed another opportunity to further punish the British.

As soon as the boarding party came back, Courage ordered more shells fired at the hapless German, and the ship smoldered away. But the German crew reboarded the battered ship, managed to bring the fires under control, and beached Rauenfels to keep it from sinking. Of the 49 crew members, one was killed and the rest were captured by the Norwegians.

After that, Havock departed the scene and the First Naval Battle of Narvik was over. Both sides lost two destroyers, and three German ships were damaged. The British suffered 147 dead, the Germans 176. However, in overall terms, the battle was a British success, but not a victory as their official history termed it. The Germans were caught completely by surprise, their refueling operation was interrupted, six German iron ore ships (and one British) were sunk in the gunplay, and the German supply ship Rauenfels and much of her valuable cargo fell into Norwegian hands.

Both sides showed ample determination and courage in the battle, except perhaps Commander Bey, who held back his thirsty destroyers when he could have polished off the British ships.

Both sides also made mistakes. Warburton-Lee did not know it, but he was attacking a much larger force, taking a great risk not waiting for reinforcements. The Germans failed to maintain a proper level of alertness, and Bey dawdled when he had the enemy at his mercy, a character failing that would repeat itself in other German admirals in similar situations throughout the war.

Kriegsmarine Trapped in Narvik

But the First Battle of Narvik was not the end. Nor was it the deciding factor in the struggle for the priceless Norwegian seaport. There would be another round in the barren, smoking Ofotfjord.

The British sent another destroyer, HMS Bedouin, and the cruiser Penelope to probe the Narvik fjord to find out what had happened. Penelope’s Captain Yates recommended a dawn attack on April 12 against the German ships, noting no sign of submarines or mines in the fjord entrances.

That attack would have plenty to find. The German destroyers had not been able to refuel because of the battle. Bey signaled the bad news to Berlin: Wilhelm Heidkamp was sinking with 81 dead; Diether von Roeder was immobile and only usable as a floating battery; Anton Schmitt was sunk; two other destroyers were badly damaged; one mildly damaged; the remaining four undamaged but not refueled.

Berlin realized that nearly half of the German Navy’s destroyer force was trapped in Narvik’s desolate fjord without air cover, shot of ammunition. They had used up half their ammunition supply in the first battle. German hopes for resupply by sea were dealt another blow when the British destroyer Icarus captured the supply ship Alster in Vestfjord on April 11. Incredibly, the Jan Wellem was still intact and could still fully fuel the surviving destroyers.

Bey reported to Naval Command West on the afternoon of April 10 that none of his damaged destroyers would be ready to attempt a breakout in time to link up with two German battleships operating off Norway that evening. Only two could be refueled by dark, Wolfgang Zenker and Erich Giese.

Naval Group West told Bey at 5:12 pm on April 10 to leave with the two fueled ships as soon as it was dark. The two German destroyers ordered to break out did so at 8:40 pm. They spotted British ships in the distance and returned to Narvik.

“Clean Up Enemy Naval Forces and Batteries in Narvik”

By noon on April 11, four destroyers were ready to sail from Narvik, but Bey believed that conditions for a breakout were unfavorable. He requested permission to stay in Narvik.

That evening, things got worse for the embattled German destroyers at Narvik. Two destroyers, Erich Koellner and Wolfgang Zenker, ran aground in Ofotfjord while on patrol during the night. Koellner hit an underwater reef that left it unseaworthy. Zenker’s propellers were damaged, cutting her speed. Bey reported to Naval Group West that he had two operational destroyers, three that could do a maximum speed of 28 knots, one that could do 20 knots, and two so severely damaged they were no longer seaworthy. He planned to use Erich Koellner as a floating battery on the north side of Ofotfjord, just east of Ramnes, the Diether von Roeder in a similar role in Narvik harbor.

On shore, the shipwrecked sailors were mustered into ad hoc naval infantry battalions, equipped with recoverable weapons, equipment, and supplies from both the sunken German destroyers in harbor and Norwegian stores at a nearby depot. The Germans also continued to bring ashore and set up the heavy guns from the armed British merchant ships in the harbor.

Now the British showed determination. The Admiralty ordered the Home Fleet’s commander, Admiral Sir Charles Forbes, to “clean up enemy naval forces and batteries in Narvik by using a battleship heavily escorted by destroyers, with synchronized dive-bombing attacks from [the aircraft carrier] Furious.”

The action would be a purely naval continuation of the attack of April 10, only with overwhelming force. It was a risky operation sending a battleship into the restricted waters of Ofotfjord, which could still be full of mines and U-boats.

There was no land component with the assault. The British were not coordinated enough with their land and sea operations to bring in ground troops to secure Narvik and its premises. It would take weeks before the British troops headed for nearby Harstad would be able to attack Narvik.

The First Sinking of a German U-Boat by Aircraft

Still, the British were determined to finish off the German destroyers. The action opened on April 12 at 6 pm, when nine British Fairey Swordfish from Furious swooped in to divebomb the German destroyers. The rickety biplanes were configured to work as torpedo bombers, and the crews were not trained for this type of attack. From altitudes of 400 feet, the German destroyers were not hit. Instead, two captured Norwegian patrol boats were. Two aircraft were lost to intense and accurate fire. A third was lost in the night landing on the carrier.

A second wave of nine British aircraft ran into a snowstorm and had to head back to Furious. The attack did little damage, but it did slow up repair efforts on Erich Koellner, preventing it from taking up its floating battery position.

By listening to British radio signals, the Germans concluded the British would attack on the afternoon of April 13. Bey ordered all seaworthy destroyers disposed so that they could surround the lighter British naval forces as on April 10. The nonseaworthy ships were to go to action stations where they stood, and Koellner was to be placed at Tarstad east of Ramnes as a floating battery.

Appointed to command the British attack force was Admiral W.J. Whitworth, who flew his flag from one of the Royal Navy’s legendary warships, the battleship HMS Warspite, a veteran of the Battle of Jutland, under Captain Victor A.C. Crutchley, who held a Victoria Cross from the World War I raid on Ostende. Warspite was one of the “cocks” of the fleet, packing 15-inch guns and a well-trained crew. Escorting her were the destroyers, Icarus, Hero, Forester, Cossack, Kimberly, Foxhound, Bedouin, Punjabi, and Eskimo.

This time the British made no attempt at surprise, depending instead on massive force. The passage through Vestfjord took place in full daylight. Warspite launched one of her Supermarine Walrus seaplanes, which spotted, dive-bombed, and sank U-64 at the mouth of Herjangsfjord with a 100-pound bomb. It was the first sinking of a German submarine by aircraft during the war. Eight German sailors died in the attack.

Whitworth’s armada steamed into Ofotfjord. As Warspite entered the area, U-46 spotted the huge dreadnought and prepared to attack. Just as it was ready to do so, the submarine collided with an underwater ridge and had to surface; it managed to escape without being spotted. Only after the war did the British realize how close they came to losing Warspite.

“Just Like Shelling Peas, Sir.”

Erich Koellner, still capable of seven knots and carrying only a skeleton crew, was escorted by Hermann Kunne in Ofotfjord on its way to Tarstad when it spotted one of Warspite’s Walrus seaplanes. The German tin cans were three kilometers short of their goal. A short time thereafter, Hermann Kunne spotted nine British destroyers near Baroy and reported to Bey that the British had arrived.

The German destroyer spun around immediately, but the British opened fire. Zigzagging at high speed, Hermann Kunne evaded the British destroyers’ short-ranged guns and Warspite’s slow-firing 15-inchers.

Commander Alfred Schulze-Hinrichs, commanding what was left of the Koellner, decided to take his ship to Dujpvik on the southern side of the fjord, hoping to open a surprise barrage on the British destroyers with guns and torpedoes as they passed him. Erich Koellner opened fire at a range of only 1,500 meters at the first British destroyer that came in view, but it was too late. The British knew the ambush was coming. The German destroyer fired torpedoes against the British, but they missed or malfunctioned.

On Warspite, Lt. Cmdr. W.W. Fitzroy, the ship’s air defense officer, recorded his impressions of the scene. “As we passed into the narrows at the end of the long fjord I remember thinking that it was like a forward rush in rugger. We belted along at high speed, with the destroyers doing magnificent work ahead of us. The roar of our 15-inch guns reverberated from the steep, snow-covered sides of the fjord, but the explosions of the enemy torpedoes when they hit the rocks were even greater. Fortunately the enemy was prevented from firing across our track, and all the torpedoes ran parallel to us and missed. Tall columns of smoke soon marked the positions where the big German destroyers had met their end, and we passed quite close to one beached or burning wreck after another. After the battle was over Captain Crutchley jutted his beard out, removed his pipe from his mouth, and said to Admiral Whitworth, ‘Just like shelling peas, sir.’”

The British destroyers Bedouin, Punjabi, and Eskimo all had their guns trained to starboard and on Koellner as they rounded the Djupvik Peninsula and opened up on the lone German ship. However, it took shells from Warspite to silence the Koellner. She sank at 12:15 pm, riddled with hits. Thirty-one of her crewmembers were killed and 35 wounded. The survivors were captured by Norwegians.

Hermann Kunne continued toward Narvik on a zigzag course at 24 knots, laying smoke to shield herself and the other German destroyers exiting Narvik harbor to meet the British. Bey’s force consisted of Hans Ludemann, Wolfgang Zenker, and Bernd von Arnim. Georg Thiele and Erich Giese, unable to get underway, stayed behind in Narvik harbor.

Scuttling the Fleet

Knowing the British had brought in a battleship and her heavy guns, Bey would have been wise not to face the British in the relatively open waters of Ofotfjord but should have maneuvered into narrower areas, where Warspite could not sail.

But the British force was within range when the three German destroyers came abreast of Ballangen Bay. Hans Ludemann opened the gunplay at 17,000 meters, and the long-range gun battle that followed was ineffective on both sides. The Germans tried to close the range for a torpedo attack but were driven off by Warspite’s heavy guns.

The battle lasted an hour, and all five seaworthy German destroyers took part. British fire did not hit the fast-moving German destroyers, and the dive-bombers from Furious were ineffective, too, dropping 100 bombs to no avail. Two British aircraft were shot down.

But the Germans had given way, retreating down the fjord toward Narvik. Within an hour, they had exhausted almost all of their ammunition, and Bey’s mission went from holding off the British to saving the lives of his crew and preventing the British from capturing his vessels. He ordered his destroyers to withdraw under a smokescreen. Hermann Kunne failed to receive Bey’s order and withdrew under pressure into Herjangsfjord. After firing off her last rounds, the destroyer was scuttled.

Erich Giese exited Narvik harbor at the same time the other destroyers were withdrawing into Rombakfjord. Six British destroyers poured shells into her, which started uncontrollable fires. Lt. Cmdr. Karl Smidt, Erich Giese’s captain, ordered the ship abandoned at 2:30 pm. The destroyer sank quickly in deep water, and 85 men died. Just before going down, Erich Giese put a torpedo into Punjabi, forcing the destroyer to withdraw from the battle.

Diether von Roeder had engine problems and stayed tied up to a pier. Warspite and a group of destroyers approached the pier, and the German destroyer opened fire on them, putting seven shells into Cossack, forcing her to beach. After Diether von Roeder exhausted all her ammunition, her crew scuttled her with demolition mines. HMS Foxhound, coming alongside to board the German, just missed being incinerated by the blast.

Out of ammunition, Wolfgang Zenker and Bernd von Arnim retreated southeastward to the end of the fjord, called Rombaksbotn. There the ships were scuttled. Georg Thiele and Hans Ludemann still had some ammunition and torpedoes left and took up positions to strike a final blow against the British, which bought time for the crews from the scuttled ships to row ashore.

Warspite did not follow the German destroyers into Rombakfjord but stood off while the escorting destroyers steamed in, battle ensigns snapping from their masts. After firing its last shells, the crew of Hans Ludemann scuttled the destroyer.

“Stand by to Sinking Ship”

Georg Thiele was the last destroyer standing, and she fought on, trying to buy time for her sisters to scuttle themselves and send their crewmen ashore. When Eskimo steamed in at close range, Georg Thiele launched her very last torpedo, which hit the forward part of the British destroyer. The explosion ripped off the Eskimo’s forecastle, killing 15 sailors. Eskimo reversed course, which created a traffic jam of destroyers behind her, but their shells still whistled in on Georg Thiele, damaging her, killing everyone on the bridge except Commander Wolf.

Wolf logged in his combat report, “Our gunfire had become irregular and weak, consisting largely of single shells fired at random. Gun No. 2, with which telephone communication had failed, received orders by shouting from the bridge. Nos. 3 and 4 had suffered interruption in their ammunition supply, and No. 5 was running out. The forward position had received a hit, killing one man and wounding two. With the gunnery officer lying momentarily stunned on the deck, the fire-signaller ordered rapid fire on his own initiative. When nothing happened, the gunnery officer called the bridge and reported, ‘Am receiving no more ammunition!’

“At about the same time further hits were sustained on the W/T office, the bridge and the after superstructure.

“The captain gave the order, ‘Stand by to sink ship!’ and set the engine-room telegraph to ‘full speed ahead’—the operator being dead and the coxswain badly wounded—and ran his ship against the steeply rising rocks, the bows lodging amongst them. Then he gave the order ‘Abandon ship!’ Part of the crew then jumped into the water from the port side, while the rest landed directly over the forecastle. The captain himself left the ship after destroying the last secret documents. (depth of water 105 meters) The wounded were carried to land and taken to cover….”

Without shells or torpedoes left to fire, Wolf beached the destroyer at high speed near Sildvik. The tin can capsized, and the aft portion sank at 3 pm while the forward part remained beached. Some 14 crewmen were killed and 18 wounded.

With Georg Thiele’s grounding, the battle was over. At 5:42 pm, Whitworth reported to London that a German submarine and all German destroyers were sunk. He considered the idea of landing troops in Narvik but rightly determined that his landing parties would be outnumbered by the 2,000 German troops in the city. Narvik would have to wait until more ground troops were brought up.

He was right. The 24th Brigade, assigned to Narvik, was still headed for Harstad. It would be weeks before the British and French would be in position to attack the city. Whitworth also worried that his battleship would be an easy target in the fjord. It was time to go, and the force began withdrawing at 6:30 pm.

The German defenders were now in a desperate plight. Even with the addition of 2,100 shipwrecked sailors to the defense in an improvised regiment, Dietl’s men were on their own, far from home, blockaded by sea, and dependent on supplies brought in through neutral Sweden, the result of German diplomatic pressure.

A Crippling Loss For the Kriegsmarine

The loss of 10 destroyers would also cripple the German Navy. It was a staggering 45 percent of their destroyer force. For the duration of the war, German naval deployments would be tempered by the shortage of escorts for capital ships.

The victory was one of the few bright spots for the British campaign in Norway, which was otherwise a massive disaster. Warburton-Lee’s heroics and Whitworth’s overwhelming use of firepower resonated at home and abroad. The Germans would be far less aggressive with their navy in the future and show timidity in other battle situations, handing the British victories and infuriating Hitler, who had little use for the surface navy in the first place.

Such assessments lay in the future as Warspite checked her fire and began the withdrawal. The 140 survivors of Hardy were moved from the wrecked ship to the village of Balangen where they—along with 47 ex-prisoners freed from the Jan Wellem—were cared for by local Norwegians. British losses in Second Narvik were small: 41 killed (15 on Eskimo, 14 on Punjabi, 11 on Cossack, and one on Foxhound). No British destroyers were sunk, but most sustained minor damage from German shells. Eskimo, Cossack, and Punjabi were heavily damaged and required repairs. In the engagements, 276 Norwegians, 316 Germans, and 188 British were killed.

Also left behind as eyesores and hazards were the wrecks of the German destroyers, which remained for years, twisted metal lying half out of the waters of the fjord. Over time, the Norwegians scrapped the remaining ships one by one, so that the only remnant left lies 15 kilometers east of Narvik. The wreckage of the Georg Thiele, shredded, battered, and covered with rust, still sits where she was driven aground on the afternoon of April 13, 1940.

My father served on HMS F67Bedouin during the battle of Narvik.

He was nineteen years old and during the battle he was trainer on B gun.

The assertion in this article that U-64 was the first U-boat sinking by an aircraft alone is incorrect.

The sinking described in this article took place on 13 April 1940.

The first sinking of a U-boat by an aircraft alone occurred on 11 March 1940, just over a month before the action in this article. U-31 was sunk by an 82 Squadron Blenheim in the Heligoland Bight.

Uboat.net described the action.

“11 Mar 1940. U-31 was the first U-boat to be sunk by an aircraft in WWII. She was on sea trials in the Heligoland Bight following a refit when Squadron Leader Miles Delap came out of low cloud in his Blenheim and bombed her, sinking her almost immediately.”

The boat was subsequently raised and repaired, only to be sunk a second time in November.

https://uboat.net/boats/u31.htm