By John McManus

Inside the shabby tent that served as his command post on Peleliu, a despondent Maj. Gen. William Rupertus sat on his bunk, slumped over with his head in his hands. As commander of the 1st Marine Division, he had expected to take the little coral-reefed island in the Palau chain in a mere three days’ time. He had even been foolish enough to communicate that optimistic expectation during a pre-invasion speech to his men. However, when his three regiments stormed ashore on September 15, 1944, they found a much different situation awaiting them than the one the general had described.

The Japanese “Absolute Defense Zone”

Rupertus did not know it, but at Peleliu the Japanese were unveiling a new strategy. Instead of defending the island at the waterline and wasting their strength on futile banzai counterattacks, they prepared an inland defense amid ideal terrain for such a holding action and resolved to bleed the Marines into nothingness. The new strategy, devised by Japanese premier Hideki Tojo and Lt. Gen. Sadae Inoue earlier that year, was based on the recent string of American successes in the Pacific War. Realizing that Japan simply did not have the resources to stop American advances indefinitely, the pair decided on a plan to make U.S. troops pay dearly for every island they took. Perhaps a negotiated peace was still possible, one that would lock into place previous Japanese conquests in China and Southeast Asia.

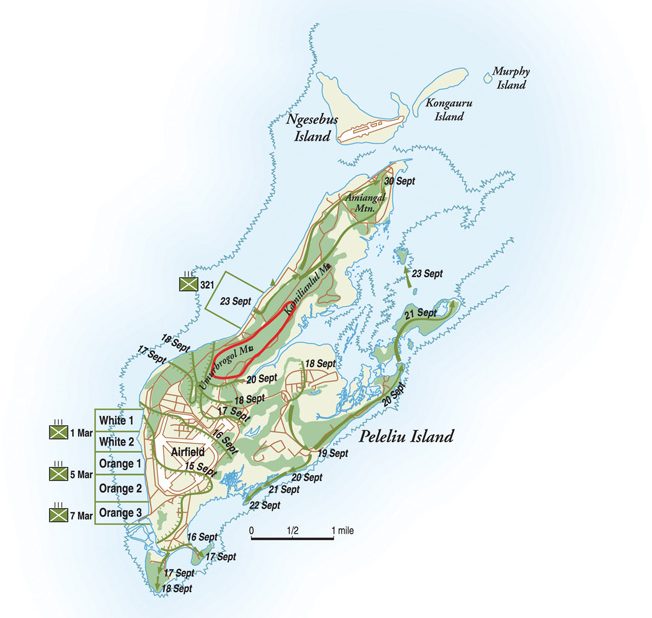

Tiny Peleliu, with its operational airfield, was designated as part of the Absolute Defense Zone, a last-ditch protective cordon safeguarding the Japanese home islands. Inoue handpicked an extremely competent and resourceful officer, Colonel Kunio Nakagawa, to take command of Peleliu’s defenses. Arriving on site in April, Nakagawa had immediately set to work strengthening the six-mile-long by two-mile-wide island, which was shaped like a lobster’s claw. The island’s natural topography favored the defenders. While the suspected landing beaches on the southwestern end of the island were fairly level, an imposing chain of craggy hills, abrupt drop-offs, and steep ravines, known collectively as the Umurbrogol Mountains, dominated the center of the island. It was there that the majority of Nakagawa’s veteran 10,000-man force would make its stand. The defense effort was given the optimistic title, “Palau Group Sector Training for Victory.”

The Japanese strategy seemed to be working all too well. Despite three days of thunderous bombardment from four American battleships and various cruisers in Rear Admiral Jesse Oldendorf’s Heavy Strike Force, the Marines had suffered 1,300 casualties on the first day of the invasion. In the following days, the fighting had grown even bloodier as the Marines attempted to take the Umurbrogol, which they nicknamed Bloody Nose Ridge. It was literally hellish work. “Along its center, the rocky spine was heaved up in a contorted mass of decayed coral, strewn with rubble, crags, ridges and gulches thrown together in a confusing maze,” an after-action report explained. “There were no roads, scarcely any trails. The pockmarked surface offered no secure footing even in the few level places. It was impossible to dig in: the best the men could do was pile a little coral or wood debris around their positions. The jagged rock slashed their shoes and clothes, and tore their bodies every time they hit the deck for safety.”

Even under ideal circumstances in peacetime, the ground would have been quite difficult to traverse. “There were crevasses you could fall down through,” Sergeant George Peto recalled. “It was a horrible place. If the devil would have built it, that’s about what he’d have done.” It was difficult to find cover, and the nature of the ground multiplied the fragmentation effect of mortar and artillery shells. “Into all this the enemy dug and tunneled like moles; and there they stayed to fight to the death,” an officer in the 1st Marine Regiment wrote.

To the Americans, the Japanese cave defenses were unbelievably elaborate. According to one Marine report, they were “blasted into the almost perpendicular coral ridges. The caves varied from simple holes large enough to accommodate two men to large tunnels with passageways on either side which were large enough to contain artillery or 150mm mortars and ammunition.” Some of the caves even had steel doors. All of them were well camouflaged, with nearly perfect fields of fire. Naval gunfire, air strikes, and artillery only had so much effect against these formidable hideouts. Only infantry and tanks could hope to destroy them, and this had to be done at close range, under extremely dangerous circumstances. It was a recipe for heavy casualties—if not outright disaster.

Operation Stalemate II

From the American perspective, the invasion of Peleliu had been snakebitten from the start. Ironically code-named Stalemate II, the seizure of Peleliu and nearby Angaur Island were aimed at protecting the right flank of General Douglas MacArthur’s long-envisioned return to the Philippines. Disagreements had flared between the Army and Navy over the ultimate goal of the operation. Navy Admiral Chester Nimitz favored bypassing the Philippines altogether to strike at Okinama, Formosa, and the Chinese mainland. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was forced to referee the dispute, coming down on the side of MacArthur. Peleliu suddenly emerged as the red bull’s eye in the center of America’s Pacific map.

Changes in the time frame, command structure, and combined Army-Marine unit cooperation further hamstrung the operation, to such a degree that Nimitz’s righthand man, Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, commander of the Western Pacific Task Force, recommended canceling the invasion of Peleliu altogether. For reasons never sufficiently explained, Nimitz overruled Halsey. The invasion continued apace.

Under the agreed-upon plan, the 1st Marine Division landed three regiments abreast on the southwestern beaches at Peleliu. The 1st Marine Regiment, commanded by Colonel Lewis “Chesty” Puller, landed on White Beach at the far left (or north) of the assault. The 5th Marines came in on the center at Orange Beach, and the 7th Marines landed farther south. From the outset, Puller’s regiment experienced the most difficulties. Given the assignment of wheeling left and attacking the high ridges of the Umurbrogol, the regiment advanced only 100 yards from shore before striking the 30-foot-high ridge rechristened “the Point” by the Marines.

The true horror of the fighting was almost indescribable. The ridges were steep, so much so that some were little more than sheer rock faces, dotted only with fortified caves. The rocky, crevassed ground was so unstable that troops could not hope to keep their footing, much less maneuver in any coherent fashion. Under perfect circumstances, it would have been difficult to overpower such a formidable network of caves. Under these conditions, it was a veritable impossibility, even for the gallant Marines. One of Puller’s battalion commanders, Major Ray Davis, who would later earn the Medal of Honor in Korea and command the 3rd Marine Division in Vietnam, referred to the Umurbrogol as “the most difficult assignment I have ever seen.”

“War is Terrible, Just Awful”

As was usually true in any ground attack, the riflemen led the way and faced the greatest dangers. They climbed the hills in small groups, supported at a distance by machine gunners and mortar men who generally fired from fixed positions. “As they toiled, caves and gulleys [sic] and holes opened up on them,” a Marine, observing from the vantage point of a machine gun post, recalled. “Japanese dashed out to roll grenades down on them, and sometimes to lock, body to body, in desperate wrestling matches.”

Many Americans were ripped apart by machine-gun bullets or fragments. Some died instantly. Others bled to death slowly while calling vainly for help. Lieutenant Richard Kennard, a forward observer with G Battery, 11th Marine Regiment, was just behind the lead troops, calling in supporting artillery fire, watching young infantrymen get hit. “War is terrible, just awful,” he wrote to his family. “You have no idea how it hurts to see American boys all shot up, wounded, suffering from pain and exhaustion, and those that fall down, never to move again.” Many times he came close to getting blown to bits by uncannily accurate mortar fire.

For the Marines, there was almost no way to avoid the accurate enemy fire. Anyone spending enough time on the ridges got hit sooner or later. Any movement drew fire. One tank platoon leader from the division’s 1st Tank Battalion watched helplessly as his tank’s supporting infantry squad was decimated by mortar fire. Later, with bitter tears streaming down his face, the platoon leader told his battalion commander: “We couldn’t do enough for them. We couldn’t reach the mortars which killed them like flies all around us.” This was why, in the recollection of another tank officer, “the infantry inspired all who witnessed its indomitable heroism to do one’s damnedest.”

After only a few hours, understrength companies of 90 men were down to half that size. Privates were leading platoons. Squads consisted of a few fortunate stalwarts. “As the riflemen climbed higher they grew fewer, until only a handful of men still climbed in the lead squads,” Private Russell Davis, a member of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, wrote. “These were the pick of the bunch—the few men who would go forward, no matter what was ahead. They are the bone structure of a fighting outfit. They clawed and clubbed and stabbed their way up,” Davis said. “The rest of us watched.”

Because of the Golgotha-like terrain, the terrible casualties, and the chaotic confusion of the fighting, units lost any semblance of organization, deteriorating into little more than random groups of survivors. “There was no such thing as a continuous attacking line,” wrote Lt. Col. Spencer Berger, whose 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines was also being chewed to pieces. “Elements of the same company, even platoon, were attacking in every direction of the compass, with large gaps in between. There were countless little salients and counter salients.” Commanders measured gains in yards. Anything in triple figures was a good day’s work. At night, Japanese infiltrators, sometimes operating in squads, counterattacked the fatigued Americans. The eerie ridges rang with the desperate, animal-like cries of men struggling to kill one another.

The Inspiring Lewis “Chesty” Puller

On the day of the invasion, Colonel Puller’s 1st Marines had numbered 3,251 men. Even before attacking the Umurbrogol the unit had already lost 900 men. By September 21, after just four days among the ridges, the 1st Marines had taken only a few hundred dearly won yards of the Umurbrogol, at the cost of nearly 2,000 casualties. Companies were down to 10 men. Few platoon leaders or company commanders were still standing. Most of the sergeants were dead or wounded as well. Puller had culled out his rear areas of cooks, bakers, signalmen, litter bearers, and engineers to refurbish his line companies, but the Umurbrogol had consumed them too. The 1st Marine Regiment was being destroyed.

Puller, shirtless in Peleliu’s 100-degree heat, was still carrying fragments from a wound suffered at Guadalcanal. The wound was infected, swelling his thigh to twice its normal size. He walked with the help of a rifle, a cane, or soldiers’ helping hands. Already he was a legend in the Marine Corps, a fire-breathing combat leader who exemplified everything a Marine officer should be. He had come up through the ranks, serving all over the globe with the Old Corps of the pre-World War II era. Basically, he was to the Marine Corps what George Patton was to the Army—a colorful, unforgettable household name who embodied the aggressiveness of total victory. As with Patton, Puller believed in leading from the front. He was a warrior in the truest sense of the word (his detractors saw him as a “warmonger”).

Diminutive and almost gnome-like, Puller always seemed to be wherever the action was thickest, talking to men, joking with them, inspiring them. His command post was usually close to the front lines, especially at Peleliu, where it was probably too near the fighting since his staff officers spent as much time taking cover as doing their jobs. To him, leading troops in combat was the highest calling. He had a special connection with enlisted men like Sergeant George Peto. At one point during the terrible fighting on Peleliu, Peto was feeling downcast, exhausted, and generally dispirited. Then he saw the colonel who greeted him amiably: “Hi son.” Peto instantly felt better. “That encounter did more for my well-being than a good drink of cool water, which I was in bad need of. I would have followed that man to hell and that’s exactly what we did at Peleliu.”

Others felt the same way. Pharmacist Mate 3rd Class Oliver Butler, a young Navy corpsman in E Company, 1st Marines, had been struggling for days to save countless numbers of badly wounded men. As the sun set one night, he saw the colonel strolling the front lines as if out for an evening walk. Puller stopped at Butler’s position and actually seemed to know him: “How are you doing, Butler?” Stunned and flattered, Butler replied: “I’m doing fine, Chesty, but we’ve sure lost a lot of men and I hope we get some replacements up here tomorrow.” Puller seemed to understand completely. “I know, son, but hang in there and keep your eyes open and your ass down.” Butler later wrote, “Among the reasons Chesty Puller’s troops liked him and admired him was the fact that he was a leader who actually and personally led and the fact that his personal courage was never in doubt.”

Puller’s Achilles’ Heel: “He Believed in Momentum”

Inspirational though he was, Puller’s leadership at Peleliu left something to be desired. His brother had been killed in another Pacific battle, and he burned with hatred for the Japanese, an enmity that perhaps took away some of his focus. He believed that the best way to win was through the pressure created by constant, unrelenting attacks. “He believed in momentum,” General Oliver Smith, Rupertus’s second in command at Peleliu, commented. “He believed in coming ashore and hitting and just keep on hitting and trying to keep up the momentum until he’d overrun the whole thing [island]. No finesse.”

Some members of the 1st Marines never forgave him for the losses the regiment suffered at the Umurbrogol. “Chesty Puller should never have passed the rank of second lieutenant,” Pfc. Paul Lewis later said of his colonel. Sergeant Richard Fisher thought of him as a tragic caricature of his own aggressive image. “All battles are ‘training exercises’ for men like Puller, and it was just another rung up his ladder. Puller was a man who could not live long without war.” Captain Everett Pope, one of his company commanders, was anything but a fan of Puller, whom he thought of as a mindless butcher. “I had no use for Puller,” said Pope, who would win the Medal of Honor at Peleliu. “He didn’t know what was going on. The adulation paid to him these days sickens me.” General Robert Cushman, who served as commandant of the Marine Corps, believed that Puller was a great combat leader who nonetheless could not understand anything except constant attacks, regardless of the circumstances. “He was beyond his element in commanding anything larger than a company—maybe a battalion—where he could keep his hands on everything and be right in the middle of it.”

After six days of fighting, the 5th and 7th Marines had largely achieved their objectives, but the 1st Marines were still locked in a hand-to-hand fight with Japanese defenders on the Umurbrogol. The legendary Puller was partly to blame. In his mind, the Japanese were no match for his Marines. He would defeat the enemy by overwhelming them. Although this aggressiveness was generally laudable, at the Umurbrogol it did not serve him well. By and large, he simply hurled his regiment into frontal attacks with few adjustments and little maneuvering, “like a wave that expends its force on a rocky shore,” in the estimation of one of Puller’s officers. Chesty did this with utter, sustained ruthlessness and not much in the way of fire support. To be fair, he did not have much of the latter to call upon, especially artillery. He might possibly have sidestepped the Umurbrogol, working his way up the west coast of Peleliu to encircle the Japanese in their caves, but that would have left the beachhead vulnerable to Japanese counterattacks.

Still, with all that taken into consideration, Puller seemed to have little grasp of the impossibility of what he was telling his men to do. Day after day, he cajoled, threatened and coaxed his commanders into launching more and ever costlier attacks. When Puller ordered his 2nd Battalion commander, Lt. Col. Russell Honsowetz, to take a hill one day at all costs, Honsowetz complained that he no longer had enough men. “Well, you’re there, ain’t you, Honsowetz? You get all those men together and take that hill.” Puller clearly wanted quick results regardless of the consequences. Amid the bloodbath, he simply would not admit to himself or anyone else that his regiment could not achieve the impossible. Nor did he have much appreciation for the challenging terrain. He even turned down an opportunity to fly over it for a better look, saying he had plenty of maps.

Sometimes positive characteristics can actually become a weakness. In this case, Puller represented aggressiveness, valor, and inspirational leadership, all ingredients that make the Marine Corps great. But he also demonstrated the tendency of Marine officers to overrely on these strengths to the exclusion of all else. His repeated, mindless frontal attacks were the American version of banzai—almost as costly, and every bit as fruitless.

The Disastrous Orders of William Rupertus

At the Umurbrogol, Puller was only following the orders of Rupertus. To the general went the lion’s share of the blame. “The cold fact,” one officer wrote, “is that Rupertus ordered Puller to assault impossible enemy positions daily till the First was decimated.” Puller might well have protested or demurred, but Rupertus probably would have relieved him. “It was more or less of a massacre,” Puller later admitted. “There was no way to cut down losses and follow orders.”

There seemed to be no end in sight to the carnage, and the longer it persisted the more heavily it weighed on the 54-year-old Rupertus, edging him toward a breaking point. A 30-year veteran of the Corps, Rupertus had once been a champion marksman (he even penned The Rifleman’s Creed). In the 1930s, while stationed in China, he had lost his wife and two of his children to scarlet fever. By most accounts, he was never the same after that tragedy. He grew more reticent, withdrawn, and dour. Earlier in World War II, he had served as assistant division commander of the 1st Marine Division until being promoted to the top job in late 1943. He was aloof from his men and frosty with his staff, especially the able Oliver Smith, whom he treated like an unwanted disease. Rupertus was a poor judge of terrain and tactics. He was rightfully proud of the Marine Corps but allowed that pride to morph into fierce contempt for the Army and the supposed incompetence of soldiers. At Peleliu, his men paid dearly for his interservice chauvinism.

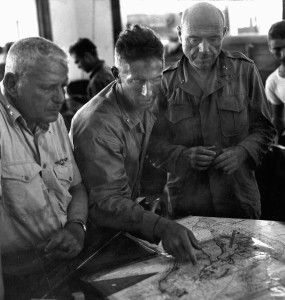

Rupertus was slow to react to the conditions on the ground. Denying the obvious reality that the battle would last longer than three days, he had dispensed unceasing orders to attack, particularly in the Umurbrogol. Because he had broken his ankle in a prelanding exercise, thus limiting his mobility, he was generally confined to his command post. Like some sort of latter-day chateau general, he had been spending much of his time on the phone, snarling at his subordinates to “hurry up” and capture the island. As the casualty numbers piled up, he seemed divorced from reality. One day, during the height of the 1st Marine Regiment’s struggle for the Umurbrogol, a newspaper correspondent came back from the front lines and told the general how many dead Marines he had just seen. At first, Rupertus tried to deny it, but realizing that the reporter knew what he was talking about the general commented, “You can’t make an omelet without breaking the eggs.”

Now, sitting on his bunk, Rupertus looked at one of his staff officers and said, “This thing has just about got me beat.” The general was thinking about stepping down and handing over command to Colonel Harold “Bucky” Harris, commander of the 5th Marine Regiment. But the staff officer, Lt. Col. Harold Deakin, sat down next to Rupertus, put his arm around his commander, and consoled him. “Now, General,” he said, “everything is going to work out.” Rupertus could only shake his head sadly and resume his brooding.

A War of Pride

The general’s main problem was narrow-minded, self-defeating pride. The 1st Marine Division was part of the III Marine Amphibious Corps, under Marine Maj. Gen. Roy Geiger. The other unit under Geiger’s command was the Army’s 81st Infantry Division. Even as the Marines struggled to secure Peleliu, elements of the 81st had overrun nearby Angaur. By September 19, the division’s 321st Infantry Regiment was available to reinforce the Marines at Peleliu. Rupertus knew how badly his division needed the Army’s help at the Umurbrogol. Yet, for days he refused to even consider this option. He was absolutely determined that his division would take Peleliu alone.

Contemptuous of the Army, Rupertus would not ask for help from mere soldiers, even as his own men died in droves. “This reluctance to use Army troops was very noticeable to the Corps staff,” Colonel William Wachtler, Geiger’s operations officer, later wrote. “It is probable that he [Rupertus] felt, like most Marines, that he and his troops could and would handle any task assigned to them without asking for outside help.” One Marine junior officer, writing to his family, put it even more succinctly. The brass, he said, “would never call in the Army like this, for it would hurt the name of the Marine Corps, I suppose, to let the world know that ‘doggie’ reinforcements had to be called in so early!!”

Geiger, however, thought differently. From D-Day onward, he was ashore at Peleliu. Brave and energetic, he roamed the battlefield, constantly gathering information on what was happening. He had a low opinion of Rupertus and had never gotten along particularly well with him. For several days, he watched as the situation at Umurbrogol grew worse. He considered relieving Rupertus but did not like the idea of firing a Marine division commander in the middle of a fight. Instead, on September 21, he finally took matters into his own hands after a visit to Puller’s command post. Shirtless, with a corncob pipe in his mouth, Chesty limped around on his swollen leg while briefing the corps commander. Colonel William Coleman, a member of the corps staff, had the impression that Chesty was completely exhausted. “He was unable to give a very clear picture of what his situation was.” Geiger asked him if he needed reinforcements and Puller “stated that he was doing alright with what he had.” This was a crucial moment when Chesty could have asked for the help he so badly needed but, like Rupertus, he could not bring himself to do so.

Puller’s condition and his tenuous grasp of reality were the final straws for Geiger. The corps commander believed that Puller should have flanked and enveloped the Umurbrogol rather than attacking it head on. Geiger proceeded immediately to Rupertus’s command post and told Rupertus that the 1st Marine Regiment was finished as a fighting unit. The regiment was to be removed not just from the line but from the battle altogether, and sent back to Pavuvu where the unit could be rebuilt for future campaigns. He told Rupertus he intended to replace them with the Army’s 321st Infantry. “At this, General Rupertus became greatly alarmed and requested that no such attention be taken,” Coleman wrote, “stating that he was sure he could secure the island in another day or two.” Geiger overruled him. The battle was over for the 1st Marines, and the Army would replace them.

The Costliest Amphibious Assault in Marine Corps History

The Marines of the 1st Regiment had literally given everything they could give at the Umurbrogol. They had fought, sweated, bled, and cried. They had performed with a gallantry that was nearly superhuman. Indeed, General Smith later wondered how they were able to capture as much ground as they did. Now, at last, thanks to Geiger’s intercession, their hell on earth was finally over. As they left the line, one of them said: “We’re not a regiment. We’re the survivors of a regiment.” Another one later added: “We were no longer even human beings.”

Geiger’s decision brought an end to the costliest amphibious assault in Marine Corps history. The Marines lost 6,786 men killed or wounded at Peleliu, including a staggering 1,672 casualties suffered by the 1st Regiment in 200 hours of fighting. The 1st Battalion, 1st Regiment alone suffered a 71 percent casualty rate. By the time it was withdrawn, only 74 men were left standing from nine rifle companies. Pfc. Eugene B. Sledge, author of the classic World War II memoir With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa later wrote: “We in the 5th Marines had many a dead or wounded friend to report about from our ranks, but the men in the 1st Marines had so many it was appalling.”

In some ways the divisional commander, William Rupertus, was the final casualty of Peleliu. After the campaign he returned stateside in November 1944 to become commandant of the Marine Corps Schools at Quantico, Virginia. Worn out and shaken by the meat grinder at Peleliu, Rupertus died of a heart attack in March 1945.

Rupertus should not be blamed. His superior noted the actions from the first day and he CERTAINLY knew what his Marines would do until they were dead or relieved. If he acted as he should have, the relief would have com much, much sooner and the tactics would have changed sooner. At this point in the war, even the most experienced Marines and Admirals would have know of the success of envelopment achieved by Douglas McArthur and the ease it could have been done on this island. In fact, I don’t know anyone who even considering the event in real time that would not feel that envelopment should have been the plan from Day 1. Someday when someone writes of the human choice of fame vs terrible hardship with same outcome that this battle will figure prominently.

I suppose it’s easy to stand back 50 years later & look at a battle & say well….we should’ve done this instead & done that.

Hindsight is 20/20

??

My father served as one of Chesty Puller’s radiomen on Peleliu He was on the landing craft with Puller in the first wave, second row. He stood next to Puller as the craft hit the beach. When they had moved far enough to dig in, a mortar hit in front of my dad, killing a friend sitting next to him in the foxhole they had just dug and the major speaking to them. Told to get medical attention, the beach had become a slaughter house and my dad decided to stay with the assault because it appeared safer. My dad was directly with Puller and I never heard him say anything but praise for Puller’s leadership and decisions. Over the years Dad heard criticism of the battle and felt that these analysts just were not there. Lives were lost at night and mortars rained down on encampments. My father described Puller as a person who did not try to be more than an ordinary man doing the best he could. He said there was absolutely no pretentiousness about him and that he was truly a great leader. My dad noted that he landed early and was the last marine to leave as he was assigned to drag in telephone lines. He may have been there longer than any other marine.

There are a number of military historians that believe this operation was unnecessary. Japan had essentially no way of getting troops to the Southern Philippines let along Leyte. After the experience at Tarawa, one would have thought an important lesson would have been learned in bypassing an ineffective enemy that could not further deploy.