By David A. Johnson

“Colonel, there’s about 3,000 Japs between you and me.” Sergeant Ralph Briggs telephoned the command post of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment at about 9:30 on the night of October 24, 1942, to report what he had just seen. Allied forces were in the thick of the Battle for Henderson Field. The telephone was picked up by Lt. Col. Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller, the battalion commander. Sergeant Briggs and 46 other Marines had been sent 3,000 yards in front of the American lines to warn of any movement by enemy troops.

Colonel Puller asked the sergeant if he was certain that the Japanese were on the move. “Positive. They’ve been all around us, singing and smoking cigarettes, heading your way.”

The Japanese had been trying to retake Guadalcanal’s airfield, which the Marines had named Henderson Field, ever since the Marines had captured the half-finished runway on August 7. The airstrip was named in honor of a Marine flier, Lofton R. Henderson, who had been killed at the Battle of Midway.

During the past 21/2 months, Japanese warships had bombarded Marine positions, and reinforcements had attacked the dug-in Marines throughout August, September, and October. The Marines always managed to hold off the Japanese attacks—at the Battle of the Tenaru, at the Battle of Edson’s Ridge, and in several other vicious encounters along the Matanikau River, which formed a natural defensive barrier protecting the western approaches to the airfield.

But the Japanese refused to be deterred and kept sending reinforcements by way of the nightly runs by Japanese destroyers, which the Marines nicknamed the Tokyo Express. Another convoy of reinforcements had come ashore on October 15. Everybody knew that it would just be a matter of time before the enemy launched yet another attack against the Marines defending Henderson Field.

“It Looks Like This is the Night”

The new Japanese offensive would be personally commanded by Lt. Gen. Harukichi Hyakutake, commander of the Japanese 17th Army. He had been on Guadalcanal for the past two weeks and had brought the 17th Army’s artillery with him, including 100mm cannon and 150mm howitzers. He was determined that this attempt to capture Henderson Field would succeed and intended to use all the forces at his disposal to overwhelm the Americans.

“The time of the decisive battle between Japan and the United States has come,” Hyakutake said on October 22. He was so certain that he would win this battle that he assigned his staff to begin preparations for accepting the surrender of all American forces on Guadalcanal. He wanted the surrender ceremony to be the envy of every unit throughout the Japanese Army.

Hyakutake’s first attack began at dusk on October 23. An artillery barrage lit up the sky, prompting a Marine officer to remark, “It looks like this is the night.”

Attacked by Japanese Tanks

After the artillery came the tanks, nine or 10 of them, depending on which source is consulted. The Marines could hear them before they actually caught sight of them, clanking and clattering eastward along the coast toward the river. The first tanks that came into view were two Type 97s. One of them was stopped by a 37mm antitank gun. The second managed to make its way through the Marines’ barbed wire, where it overran a machine gun position. But luck was with the Marines. The tank ran up on a tree stump and came to a complete stop, making it a stationary target.

A Marine private reached out of his foxhole and slipped a hand grenade under one of the treads. The explosion blew the tread right off, sending the tank reeling into the surf of the Sealark Channel. A half-track went after it and destroyed the tank with its 75mm gun.

The remaining tanks did not fare any better. A barrage of flares gave the Marine antitank gunners a clear view of the approaching armor. Every one of the advancing tanks, including two 71/2-ton Type 95s, were knocked out before they could do any damage to the defensive perimeter. In the morning, their burned-out hulks littered the sandbar.

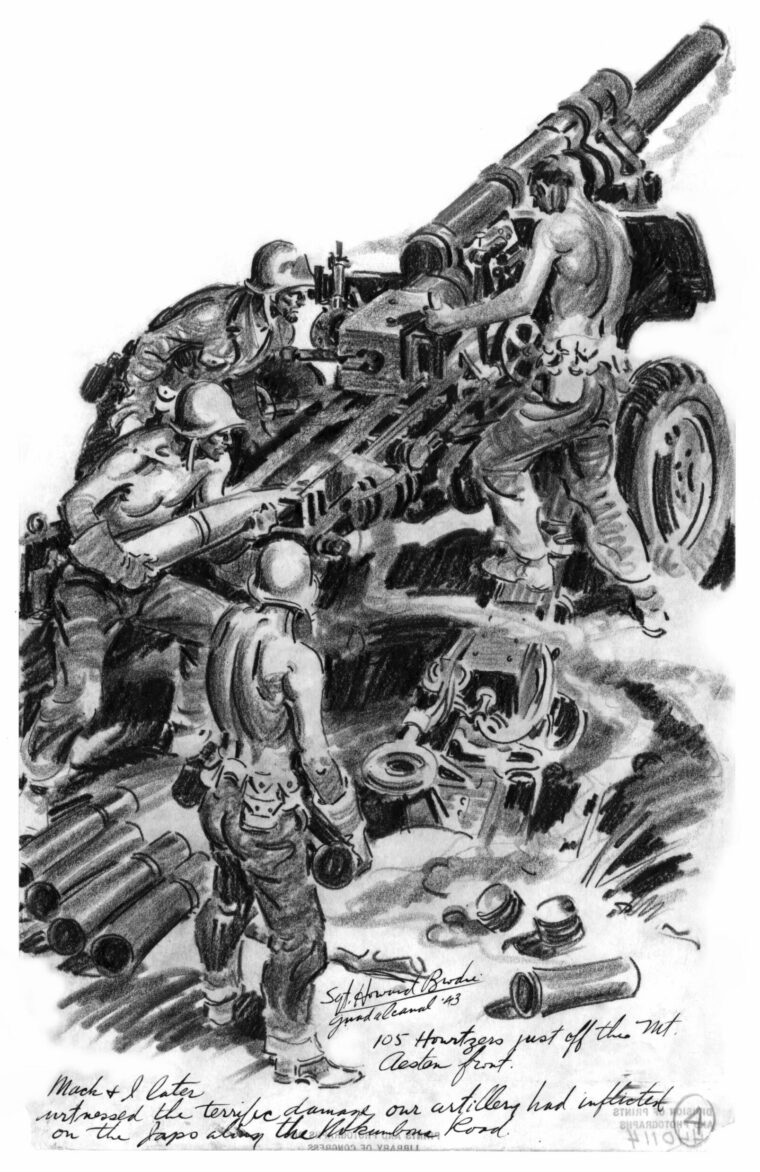

According to plan, two battalions of the 4th Infantry Regiment were to start their attack on the Marine lines behind the tanks. But the Marine artillery had the Japanese infantry zeroed in. A total of 40 howitzers supported by mortar fire had the range and dropped more than 6,000 rounds on the Japanese before they had the chance to mount any attack. The Marines could hear the screams of the Japanese during short lulls in the firing. Losses among the Japanese units were not detailed, but Marine patrols discovered about 600 dead when they examined the area the next day.

The attack of October 23 was over by midnight, a complete failure. The Marines knew that the Japanese were not about to give up and would almost certainly try again on October 24. This suspicion was confirmed when a Japanese officer was spotted studying the American lines through binoculars. The Marines spent the rest of the day repairing barbed wire around the perimeter and digging their foxholes a little deeper.

With the approach of dusk, General Hyakutake began moving again. He planned this attack to the west of the previous night’s action. The sector he had targeted was under the command of Lt. Col. Puller.

Chesty Puller: Banana War Legend

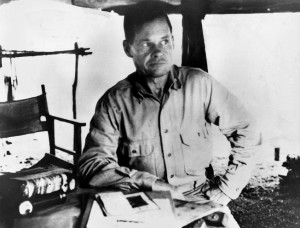

By the beginning of World War II, Chesty Puller was already something of a legendary figure throughout the Marine Corps and had already won two Navy Crosses. He had fought in more than 40 engagements during the “Banana Wars” in Haiti in the 1920s. Puller received his commission as a second lieutenant in 1924 and served two tours of duty in Nicaragua—in 1930 and again in 1932. In 1930, he was awarded his first Navy Cross. Two years later he received his second for showing “great courage, coolness, and display of military judgment.” He was called Chesty because of his massive barrel chest, although his most visible feature was his prominent chin, which one writer described as looking like “a bulldozer blade.”

“Blood for the Emperor! Marine, You Die!”

The Japanese force consisted of two wings that had a combined strength of three rifle battalions. This meant that Puller’s force was outnumbered three to one. The left wing, commanded by Maj. Gen. Yumio Nasu, passed within hailing distance of Sergeant Briggs’s outpost. The Japanese came so close that one soldier tripped over a Marine’s helmet. The right wing veered off to the west, and only one of its battalions made contact with the Marines. This unit, the 1st Battalion, 230th Infantry, began shooting at about 10 pm. After that, the firing was almost incessant.

Shortly after Colonel Puller spoke with Sergeant Briggs about the 3,000 Japanese, the telephone rang again. A company along the line reported that Japanese troops were cutting through the barbed wire along its front. Puller now knew that the enemy had made contact with his men, but he also knew that he had a problem. Sergeant Briggs and his detachment were still in position 3,000 yards to the front and would be directly in the line of fire when Puller’s Marines started shooting.

Puller telephoned Briggs to take his group to the left and to keep moving until they passed through the American lines. “Don’t fail, and don’t go in any other direction,” Puller warned. “I’ll hold my fire as long as I can.”

Briggs brought most of his men through the Marine lines the following day. Of the 46 men in his detachment, three were killed and 10 wounded. The last member of the unit turned up two weeks later.

While Puller held his fire, a shouting match broke out along the perimeter. A Japanese voice yelled, “Blood for the Emperor! Marine, you die!”

An American voice shouted back, “To hell with your Emperor. Blood for Franklin and Eleanor!” A tirade of insults and obscenities followed in two languages.

An Ill-Advised War Cry

Finally, Puller decided that he had waited long enough. “Commence firing!” he called over the telephone. Machine guns and rifles immediately opened up all along the perimeter, and artillery began firing from behind the lines. By this time, Japanese engineers had already begun snipping their way through the Marine barbed wire while infantrymen crawled toward the perimeter. In the excitement of the moment, some of the men stopped their silent crawl through the high grass and stood up. Others began shouting an edgy war cry.

This was exactly what the Japanese company commander did not want to happen. The shouting may have raised morale among the men, but it also called American mortar fire down on them. Machine-gun crews were also alerted by the noise. Blasts and fragments from the mortar shells combined with the massed machine guns killed most of the men before they could get near the barbed wire.

The machine guns that did the most damage were commanded by Sergeant John Basilone, who actually learned the finer points of handling the weapon during a stint in the Army. Because of his Army training, he was acknowledged as one of the outstanding experts of the .30-caliber machine gun in the Marine Corps. On this particular night, Sergeant Basilone needed every bit of his expertise and training. After the attack had been beaten off, Basilone had to send men beyond the perimeter to reduce the pile of Japanese bodies. The dead were stacked so high that they were blocking the line of fire of his machine guns.

“Give Us All You’ve Got”

The attack had been stopped. It was about 1 am when the firing slackened, if anyone had the time to look at their watches, but General Hyakutake was not about to give up.

A second attack began within the hour and lasted a frenzied 15 minutes. Captain Regan Fuller, commanding a battery of three 37mm antitank guns and two .50-caliber machine guns on the Marine left, could see Japanese troops massing for a charge, keeping close to the jungle for cover. His antitank guns fired one round of canister each, and the massed troops disappeared.

This was just the beginning of the Japanese attack. By this time, Puller realized that a major attack by seasoned, well-disciplined troops was under way. He telephoned the 11th Artillery several miles down the coast and told them, “Give us all you’ve got. We’re holding on by our toenails.”

“I’ll give you all you call for, Puller,” the artillery officer replied, “but God knows what’ll happen when the ammo we have is gone.”

“If we don’t need it now, we’ll never need it,” Puller insisted. “If they get through here tonight, there won’t be a tomorrow.”

“She’s yours as long as she lasts,” came the reply.

Artillery fire helped to keep the enemy attacks at bay for a short time, but the Japanese kept coming. The Japanese 29th Infantry Regiment, or what was left of it, kept up its attack against the men behind the barbed wire. Basilone made hurried visits to Puller’s command post several times during lulls in the fighting. Marines in the command post noticed that Basilone was barefoot. He reported that some of his machine guns were burning out from the almost constant firing and that his men were urinating into the water jackets to keep the guns from seizing up. When he left to rejoin his men, Basilone carried machine-gun parts and ammunition with him.

Reinforcements Arrive

At about 2 pm, Colonel Puller sent out a call for urgently needed reinforcements. After a brief delay at regimental headquarters, the 3rd Battalion, 164th Regiment—actually an Army National Guard unit with no combat experience—reached Puller’s area. A Navy chaplain, Father Keough, who had often visited the Marine positions and knew how to find them in the dark, escorted the men to the Marine lines through a tropical downpour. The Army troops were dispersed into the Marine lines by squads and platoons. By about 3:45 am, all of the reinforcements were in position.

Colonel Puller walked out of his CP in the rain to meet the incoming replacements. He did not have to go very far before the head of the relief column made himself known. Puller immediately recognized Father Keough and shook hands with him. “Here they are, Colonel,” Keough announced.

“Father, we can use them,” Puller drawled in his unmistakable Virginia accent.

Puller was not nearly as cordial with the 3rd Battalion’s commanding officer, Lt. Col. Robert K. Hall. “I don’t know who’s senior to who right now, and I don’t give a damn,” he told Hall. “I’ll be in command until daylight, at least, because I know what’s going on here, and you don’t.”

Hall understood. “That’s fine with me,” he said. “You lead on.”

“I’m going to drop ‘em off along the road,” Puller explained about the incoming troops, “and send in a few to each platoon position. I want you to make it clear to your people that my men, even if they’re only sergeants, will command in those holes when your officers and men arrive.”

Once again, Hall had no objection. “I understand you. Let’s go.”

Puller, Keough, and Hall made their way along the road in the dark and rain with the sound of gunfire on their left. Every 100 yards or so, a runner came up from the lines. Puller would assign a squad of men to go with the runner, who led the new men to the Marine lines. Within a short time, all the troops had been positioned to help fend off the next enemy attack.

A Battalion of 500 Men

When Puller returned to the command post, he was informed that regimental headquarters had telephoned. He immediately contacted the regimental commander. The officers in the CP heard Puller’s side of the conversation.

“What d’ya mean, ‘What’s going on?’ We’re neck deep in a fire fight, and I’ve got no time to stand here bullflinging,” Puller shouted into the receiver. “If you want to find out what’s going on, come up and see.” He turned to the other officers and said, “Regiment is not convinced that we are facing a major attack.”

The attacks kept coming with as much determination as before. The new arrivals got on well with the Marine veterans and were instrumental in holding off two or three more attacks. Their joining the battle was timely. Puller estimated that his battalion was down to about 500 men. When the 1st Battalion landed on Guadalcanal in September, it had a full complement of about 900 men. Before the attacks started, about 700 men had been available.

Some of the Marines relieved the new soldiers of their M-1 Garand rifles, which were semi-automatic and more suited to jungle fighting than the rifles they had been issued. The Marines had been equipped with the Springfield Model 1903, a bolt-action rifle. The Marines had not seen the M-1 before and immediately fell in love with the way the rifle fired and handled.

The colonel commanding the Japanese 29th Infantry Regiment led yet another charge against the Marine barbed wire. Machine-gun fire took its toll on the advancing Japanese. Marines armed with bayonets finished off most of the Japanese who had survived the machine guns. Another group, this time in battalion strength, began to mass for another attack, but by the time the troops were assembled, the sun had risen. Marine machine-gun fire stopped this charge at the edge of the jungle before the Japanese could even get close to the Marine lines. This was the seventh and last attack that Puller and his men had to endure on this long and brutal night.

A small contingent of Japanese troops, fewer than 100 men, had managed to break through the Marine lines. They punched a hole about 150 yards across and scattered in small groups behind the American machine guns and rifle positions. During the daylight hours of October 25, Marine patrols killed 67 of these stragglers.

Sergeant Briggs and his platoon had taken cover in the woods overnight, where they were surrounded by Japanese troops. “We gained cover in the woods where it was as cold as hell, and the Japs seemed to be all around us,” he later recalled. “We could hear them jabbering and walking so close that one Jap stepped on a Marine’s bayonet.”

When daylight finally came, Briggs and his men came under heavy Japanese mortar and machine-gun fire. Private Robert Potter jumped up and began running back and forth, deliberately drawing the fire of the enemy gunners. Most of the other men escaped while the Japanese were distracted by Potter, who was killed.

“The Night Attack is a Success!”

The commander of the Japanese 2nd Division, Lt. Gen. Masao Maruyama, had heard conflicting stories about the fighting. The first news he received was what he wanted to hear. “The right flank attacked the airfield,” an officer reported by field telephone. “The night attack is a success!”

As the night went on, Maruyama could hear the firing of American mortars and artillery, and the volume of fire seemed to be increasing. If the attack had succeeded, the enemy fire should be diminishing, not increasing. The general feared that something had gone wrong. These fears were confirmed by a telephone call from the same officer who had reported a victory earlier.

“It was a mistake about the success of the right flank,” the officer reported. “They haven’t reached the airfield yet. They crossed a large open field and thought it was the airfield. It was a mistake.”

Another officer heard about this mistake and said that he was struck with “an omen of doom.” As time passed and there were no more reports from the front, everyone’s feelings of foreboding increased.

Finally, around dawn, Maruyama received the news he had been dreading. Most of the 29th Regiment had been wiped out, and its regimental flag was missing. “That’s it,” Maruyama said.

During the daylight hours of October 25, Puller’s Marines counted 250 Japanese dead inside their lines. One of the officers, a major, had committed suicide. He felt that he had disgraced himself and his regiment. “I do not know what excuse to give. I apologize for what I have done,” he wrote in his diary, agonizing over the loss of his men and his regimental flag. “I am going to return my borrowed life today with short interest.”

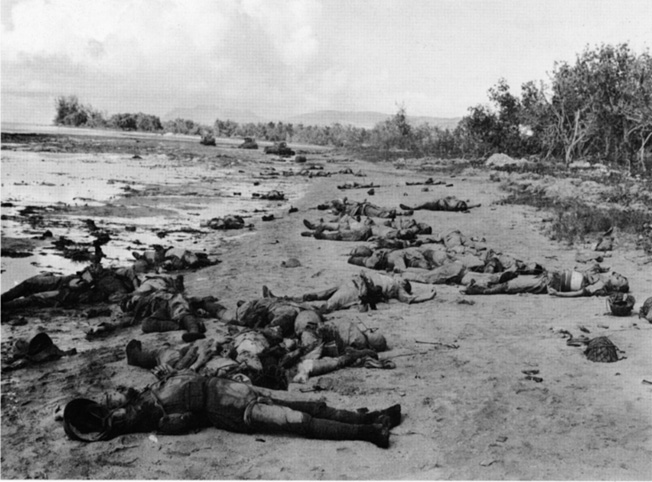

1,462 Bodies

A few days after the battle, with the bodies of the dead Japanese decomposing in the tropical heat, Puller convinced division headquarters to perform a body count. The detail that carried out the grisly assignment tallied 1,462 bodies as they buried the dead. Bulldozers dug trenches, and then the burial crew loaded the bodies into the ditches after they were counted. Finally, the bulldozers covered the trenches with fresh earth. This went on for two days.

There were also some happier moments for Puller. On the morning after the battle, the commander of the 164th Regiment gave Puller some words of encouragement. “Colonel Puller, I want you to know how happy I am to have my men blooded under you,” the officer said. “No man in my outfit, including me, had ever seen action, and I know our boys couldn’t have had a better instructor. I wish you’d break in my other battalions.”

If Puller was flattered, he did not let it show. Instead, he replied with a left-handed compliment. “They’re almost as good as Marines,” he told the bemused officer.

Medals for Puller and Basilone

Puller was awarded a third star for his Navy Cross for the night’s action. According to the citation for his decoration, “He prevented a hostile penetration of our lines and was largely responsible for the successful defense of the section assigned to his troops.”

Puller would receive two more Navy Crosses—at Cape Gloucester, New Britain, in January 1944, and at Koto-Ri, Korea, in December 1950. When he retired in 1955 with the rank of lieutenant general, Puller was the most highly decorated Marine in the history of the Corps.

Sergeant John Basilone received the Medal of Honor for keeping his machine-gun crews supplied with ammunition and for manning a machine gun himself. He was credited with stopping a Japanese charge singlehandedly and “gallantly holding his line until replacements arrived.” Basilone was killed on Iwo Jima in February 1945.

Guadalcanal: An “Island of Death”

The night had been a complete disaster for the Japanese. Not only had every attack failed to capture Henderson Field, but the failure of so many determined charges made by veteran troops began to wear away at morale throughout the Army. Reports that Guadalcanal was an “island of death” began to circulate even in remote outposts.

An interrogation session held after the battle gave a pointed indication of why Japanese troops had no success against the Marine positions in spite of their determination. “Why didn’t you change tactics when you saw you weren’t breaking our line?” Puller asked a prisoner. “Why didn’t you shift to a weaker spot?”

“That is not the Japanese way,” the prisoner replied. “The plan had been made. No one would have dared to change it. It must go as it is written.”

The inflexibility of the Japanese officers contributed to their loss of Guadalcanal. In February 1943, less than three months after Hyakutake’s disastrous attempt to capture Henderson Field, Japanese forces evacuated the island, abandoning Guadalcanal to the Americans.

Good reading.