By William McPeak

The shafted ax has been around since 6000 bc, in both peaceful and warlike uses. The so-called battle-ax cultures (3200 to 1800 bc) extended over much of northern Europe from the late Stone Age through the early Bronze Age. The first ax heads were made of stone and used by hand; a wood handle known as the haft made ax wielding easier. Techniques of handle attachment included wedging, flanging, winging, and socketing. Socketing required the haft to be drilled with a hole to fit a shaped stone through the haft or on top of it. Many stony minerals were used for the head, and the edge was sharpened on both sides and double beveled.

With the discovery of metals came the various work of accommodating axes for warfare. From rather blunt faces in rectangular shapes, the ax head took on the familiar, slightly convex front edge and tapered back to the blunted butt. By the Iron Age (1000 bc), the wedge-shaped iron ax head was the standard form, drilled near the butt for hafting. For warfare, the battle-ax was most efficient in a light design. Axes with double front and rear edges cropped up in some ancient cultures but, realistically speaking, were too heavy for real efficiency.

The Francisca: Battle-Ax of the Franks

The single-beveled edge head was soon developed. Unlike its farm implement predecessor, the battle-ax was meant to cut flesh, not wood. Roman legionaries carried a standard pickax with a short edge on a 19-inch head and a 30-inch haft. By the fifth century, a battle-ax with a narrow, wedge-shaped head, usually a flat arch or S-shaped top side with a rather flat, beveled convex edge of approximately three inches turned back at the heel in a concave sweep at the underside, appeared in northern Europe in the hands of the Franks. This ax was called the francisca (from the Latin word for Frank). The Franks made up the western German confederation that would evolve into a multipart kingdom under the Merovingian rulers and then an empire under the Carolingian rulers of the seventh and eighth centuries, particularly Charlemagne.

The francisca was used both as a throwing and close-combat weapon. The Roman historian Procopius described its use as a throwing weapon by the Franks: “Each man carried a sword and shield and an ax. Now the iron head of this weapon was thick and exceedingly sharp on both sides while the wooden handle was very short. And they are accustomed always to throw these axes at one signal in the first charge and thus shatter the shields of the enemy and kill the men.” Procopius stressed that the Franks threw their axes immediately before hand-to-hand combat, for the purpose of breaking shields and disrupting the enemy line while wounding or killing enemy warriors. The weight of the head and short length of the haft allowed the ax to be thrown with considerable momentum to an effective range of about 40 feet. Even if the edge of the blade did not strike the target, the weight of the iron head could cause serious injury.

Another feature of the francisca was its tendency to bounce unpredictably upon hitting the ground due to its weight, unique shape of the head, lack of balance, and slight curvature of the haft, making it difficult for defenders to block. It could rebound at opponents’ legs or against their shields and through the ranks. The Franks capitalized on this by throwing the francisca in volleys to confuse, intimidate, and disorganize the enemy lines before or during a charge to initiate close combat.

The francisca, after undergoing changes of the length of edge, became popular with other Germanic peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons, and made its way farther north to become a basic template for the expeditionary Vikings. The Vikings extended the francisca ax edge downward a further inch, with the underside at the heel cutting briefly back horizontally and then turning up into a deep concave arc. Called the bearded ax, the weapon would undergo changes such as sweeping into an arc at the heel of the edge. Scandinavian smiths had been working iron-edged weapons, and they usually made the ax head of iron and forged the edge into steel to make it a superior cutting face.

The Norse Battle-Ax

Another Norse style of the ninth century returned to the full arc of convex edge, tapering both the top and undersides of the head backward in a concave sweep to the haft, sometimes known as the shaved ax. This was probably the earliest broadax form and enabled a more effective sweeping cut rather than a simple chop. Although there were variations, the broadax continued to be developed from a basic one- or two-pound weapon with a haft of about 1½ feet of ash or oak. This was the common form of the European single-hand battle-ax thereafter. The Anglo-Saxon invasions of the fifth century and Viking raids from the late eighth and ninth centuries brought these early forms of the battle-ax to Britain.

By ad 1000, the Danes were popularizing a shaved ax design with as much as 12 inches of curved blade but again with the inside edges deeply concave. This was the Danish ax, with a weight of as much as four pounds and requiring a longer haft of three or four feet for both hands. In 1066, the English met the Norman invaders near Hastings with their primary professional infantry wielding a Danish battle-ax called the English long ax, which was essentially an early poleax for two-hand use.

The Ax vs Armor

The progression of improvements in edged weapons followed the improvement in armor in general. By the late 14th century, plate armor of surface-hardened steel was so resilient that steel sword points and most concussion weapons grazed off its curved surfaces. Although defined as an impact or concussion weapon, the battle-ax had an advantage over others of its class, the war hammer and the various designs of the mace and flail. The battle-ax was also an edged weapon—a powerful one. The various lengths and arcing edges of its head could inflict some massive damage when striking well. The popularity of the Danish long ax came from the force of its sweeping and cutting blows. A horseman had even better striking ability.

Although the sword still reigned as the knightly weapon, by the 12th century a variety of single-handed battle-axes were adopted by the noble class of Europe as a horseman’s weapon. Manuscript miniature paintings of the medieval period show many a battle-ax cleaving into the helmeted head of a mounted knightly opponent. King Stephen of England took up the battle-ax after his sword was broken at the Battle of Lincoln in 1141. Richard the Lionheart was supposedly a famous wielder of the battle-ax. Thirteenth-century chroniclers made the point of noting the use of the battle-ax by the nobility. James, the second earl of Douglas of Scotland, son of the great patriot James the Black Douglas, used the battle-ax, although he perished at the Battle of Otterburn in 1388. Later, French marshal Breton Bertrand du Guesclin and his companion in arms Olivier de Clisson, future constable of France, both used the battle-ax.

By the late 14th century, the noble knight put aside the battle-ax as a backup to the sword, which had undergone improvements with more tempering and narrowing of the pointed blade. Then came surface-hardened steel. With steel armor to contend with, many returned to the usefulness of the battle-ax. By this time, a basic horseman’s ax evolved with the functional need of a longer haft to use while sitting astride a horse, where one could get the most out of it. The full convex edge and swept concave head of the broadax could be used to best advantage by performing the so-called draw cut on horseback. The draw cut was an arcing overhead stroke of the curved saber blade used by the light cavalries of Islam. The result was a deadly efficient follow-through. The forward momentum on horseback made the damage that much more efficient. The horseman’s ax had a haft of up to three feet, usually requiring two hands, and a hole bored at the butt of the haft for inserting a leather thong for carrying at the saddle and winding at the wrist.

Building a More Practical Ax

In the early 14th century, the battle-ax head was further modified—but at the opposite end. The butt of the battle-ax head was flared slightly out in a small hammer-like shape for more utility. Archers carried a short ax with a hammer-like butt to pound in and sharpen stakes for a trench palisade, and it was often preferred to carrying the usual short sword. Beginning in the late 14th century, the battle-ax began to appear adorned with butt-end alternatives similar to the war hammer to help puncture that impenetrable armor. The butt of the head was extended with a spike of up to about six inches, which was used as another puncturing option and counterbalance. A well-placed and powerful hit with the spike could puncture, but the ax’s worked steel edge could put a bigger slice in armor on its own. A further option was a vertical, four-sided spike of six inches extending above the center of the head. This rather awkward stabbing weapon was used mainly for delivering the coup de grace to a fallen opponent. Although the back spike became shorter, the vertical spike fell out of favor in comparison with battle-axes and the horseman’s ax.

More practical additions were at hand. By the early 14th century, some battle-ax heads appeared with short, downward extensions from the head and along the haft to further secure it. This idea was furthered by reinforcing the haft by riveting metal bands called langets, extending partially or fully down both sides of the length of the haft. The langets were a means of protecting the battle-ax head from being sheared from the haft. A more effective solution to that outcome was to put the ax head on an all-iron or steel haft. This appeared in cylindrical and polygonal forms around the middle of the 15th century. Although heavier, the all-metal ax was also efficient. For protecting the hand against glancing and sliding blows, a small metal disk guard was added at the top of the ax grip. Something smiliar in larger form regularly appeared on the two-handed poleax.

“My Kingdom for a Horse!”

At least one king favored the battle-ax to such extent as to gamble his kingdom on it. By the later 15th century, after 100 years of fighting between England and France, a civil war erupted in England between two houses of the Plantagenets and Lancastrians with a red rose symbol and the challenging Yorkists with a white rose. This was the War of the Roses. For more than 20 years, bloody battles pitting relatives against one another continued after the Yorkists effectively took power in 1461. In 1483 Richard III seized power, becoming perhaps the most reviled monarch in English history.

Revisionists, including William Shakespeare, made a concerted effort to discredit Richard. In his play Henry VI, Part 3, Shakespeare has Richard ready to do anything to grab the throne: “Or hew my way out with a bloody axe.” The ax reference is relevant for Richard because evidence showed that from youth he practiced particularly with the battle-ax—so much so that his right arm was supposedly much more muscular than his left, as was his right shoulder and back. This probably gave the impression that he was deformed—thus the hunchback tradition.

In August 1485 it all came to a head at Bosworth Field, where Richard was defeated by Henry Tudor and a large force of Welsh archers and French mercenaries. Richard had already successfully intercepted Henry’s reserve and after the first shock had entered a swirling melee. He cleaved his way with surprising speed toward the frightened Henry, who was surrounded by bodyguards, before his horse became mired in the mud and the king threw down the ax and drew his sword for better reach. He was finally surrounded by a great mass of Welsh spearmen and cut down. Richard died bravely on the battlefield, crying out: “Treason! Treason!”—not, as Shakespeare had it: “A horse! a horse! my kingdom for a horse!”

Replaced by the Sword and the Gun

Both all-metal and wooden haft battle-axes moved into the 16th century but were increasingly upstaged by more a versatile array of swords: infantry and cavalry sabers, curve-bladed short swords, and broad swords. But the all-steel battle-ax, usually without the vertical spike, did enjoy some splendor in the art of chiseled grips and engraved and etched blades for parade and ceremonial uses during the 16th and early 17th centuries. The battle-ax was still a popular secondary weapon in eastern Europe. Ornately chiseled all-steel battle-axes were popular cavalry weapons with the Ottoman Turks in the 16th century and into the 18th century in the Middle East and India. There they were called the tabar and had more curvature on the edge than Western designs. But for Europe as a whole, practicality centered on the battle-ax transformation into two-handed forms—the many pole arms and staff weapons with ax heads: poleax, Scottish lochaber ax, Russian bardiche, and various longer halberds.

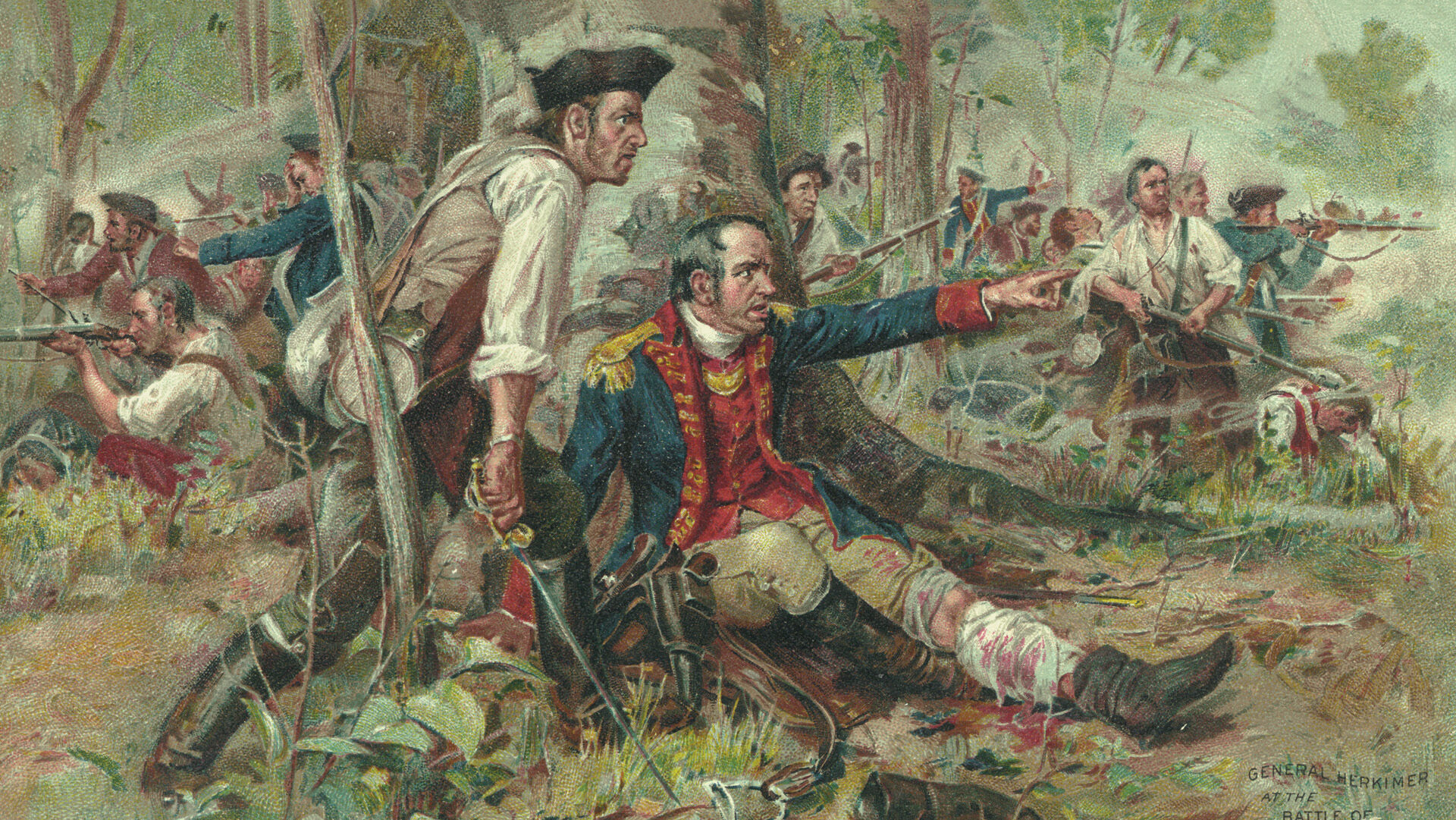

Similar weapons were still a choice on 17th and 18th century battlefields, although firearms now ruled the day. In North America, trade axes with the Viking head became the new weapon of choice for Native Americans, replacing their wood and stone tomahawks. Hand-to-hand combat with the tomahawk would by necessity become a skill developed by frontiersmen during the French and Indian and Revolutionary Wars. The U.S. Navy’s boarding ax of the late 18th century looked similar to a short bearded ax, with three or more sharp teeth at the bottom back side of the edge to rake up and clear downed rigging and burned wreckage. By the 19th century, the typical broadax tool was used in camps and on battlefields by sappers and miners and at sea for onboard tasks. In modern times it has chiefly been used for engineering tasks.

Of all the impact and concussion weapons of military history, the ax remains an important tool, whether on the battlefield, in the forest, at throwing competitions, or simply in the backyard for the more peaceable pursuit of gardening.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments