By Roy Morris Jr.

In December 1941, after four decades of play in the same sixteen eastern and midwestern cities, major league baseball was finally coming to the west coast. Saint Louis Browns owner Donald Barnes had a surefire plan: he would relocate his financially struggling team to Los Angeles and take over the local franchise rights and ballpark currently held by Chicago Cubs owner Phil Wrigley for a one-time fee of $1 million. The move would help everyone—Barnes, Wrigley, the St. Louis Cardinals (who would no longer have to share a stadium with the Browns), and major league baseball itself, which in one fell swoop would extend its reach from the Atlantic to the Pacific. At long last, baseball would truly be a transcontinental business.

Barnes intended to present his plan, complete with an intricate new schedule designed to limit cross-country train trips for opposing teams to two apiece during the season, at the annual meeting of the sixteen major league owners in Chicago on December 8. While waiting, Barnes decided to attend a professional football game between the Chicago Bears and the Chicago Cardinals at Comiskey Park. He was sitting in the stands with club general manager William DeWitt on Sunday, December 7, when the first news flash came across the radio that Japanese warplanes had bombed Pearl Harbor. In that instant, everything changed. There would be no baseball on the West Coast in 1942, and Barnes, DeWitt, and the rest of the major league owners, executives and players instead would find themselves struggling to adapt their sport—and their lives—to the unprecedented needs of a country that suddenly found itself at war.

In the massive confusion following the attack at Pearl Harbor, there was good reason to believe that the upcoming baseball season would be cancelled altogether. Many big- league players, like the rest of their outraged fellow-countrymen, were already flocking to enlistment offices across the nation. One of the first to go was 23-year-old Bob Feller, the fireballing pitcher for the Cleveland Indians. Feller, who had won 25 games for the Indians in 1941, had been en route to Chicago from his father’s farm in Iowa to attend the winter meeting when he heard the terrible news come over the radio. Although he had previously been classified 2-C (farmer) by his local draft board, Feller did not feel that it was right to retain his off-season exemption. Instead, he drove directly to the federal courthouse in Chicago, where he was sworn into the Navy by former heavyweight boxing champion Gene Tunney, who was serving as a lieutenant commander in charge of the Navy’s physical fitness program. The swearing-in ceremony was carried live on the radio throughout the country and filmed for use in motion picture newsreels. Feller shrugged off any praise for his quick enlistment. “We needed heroes,” he remembered later. “I thought I could help.”

Another American League superstar also acted quickly to enter the service. Detroit Tigers slugger Hank Greenberg had already been drafted in a special peacetime draft the previous May. Exchanging his $55,000-a-year salary for the $21-a-month stipend of an Army private, Greenberg was discharged two days before Pearl Harbor (all draftees over the age of 28—Greenberg was 30—only had to serve 180-day tours of duty). Not waiting to hear again from his draft board, the home run-hitting outfielder immediately reenlisted at his last rank of sergeant. “We are in trouble and there is only one thing for me to do—return to the service,” Greenberg said at the time. “All of us are confronted with a terrible task—the defense of our country and the fight of our lives.” Being Jewish, the war would have particular significance for Greenberg, although no one yet knew how heinous Nazi atrocities against Greenberg’s fellow Jews in Europe would prove to be.

Perhaps fittingly, the first major league player drafted after President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Selective Service Act of 1940 was Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Hugh Mulcahy. Nicknamed “Losing Pitcher” Mulcahy for the abbreviated way he was usually listed in the morning box scores, Mulcahy would eventually spend five years in the Army—unlike Greenberg, he was too young to receive an early discharge. The lowly Phillies put a photo of Mulcahy, wreathed by a “V for Victory” arrangement of bats, on the cover of their 1942 team yearbook. They had already shown how much they missed his pitching prowess by finishing 57 games out of first place in 1941, after finishing a mere 50 games out of first the year before. Mulcahy, too, downplayed his sacrifice. “I might have got hit with a line drive if I spent six more months with the Phillies,” he joked. Given the Phillies’ congenital ineptitude, that might have been more of a danger than it seemed at the time.

Baseball officials were unsure, at first, how to proceed with the season. National League president Ford Frick sent President Roosevelt a telegram pledging that “individually and collectively, we are yours to command.” And baseball’s unofficial Bible, the Sporting News, editorialized in its first post-Pearl Harbor edition that the sport was ready to close down, if need be, for the duration of the war. But FDR, heeding the hardly disinterested advice of his close friend Clark Griffith, owner of the Washington Senators, sent a letter to baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis in January 1942, clarifying the government’s position on the immediate future of the game. “I honestly feel that it would be best for the country to keep baseball going,” the president wrote. “There will be fewer people unemployed and everybody will work longer hours and harder than ever before. And that means that they ought to have a chance for recreation and for taking their minds off their work even more than before.” American League president Will Harridge eagerly accepted the morale-boosting mission. “Baseball,” he said, “may be approaching the finest opportunity for service to our country that the game has ever had, providing a recreational outlet for millions of fans who will working harder than ever to help achieve our common cause of victory.”

“No Nation Which has had as Intimate Contact with Baseball as the Japanese Could have Committed the Infamous Deed of the Early Morning of December 7, 1941″

Roosevelt’s so-called “green light” letter did not exempt players from fulfilling their military obligations, and during spring training in 1942 there were a few ostentatious hints of things to come. In Miami Beach, the luckless Phillies were put through a series of short-order drills by visiting Army officers, and the players dutifully shouldered their bats like rifles to march in step prior to an exhibition game with the Boston Braves. The drills were the brainchild of Philadelphia manager Hans Lobert, who recalled a similar stunt during his playing days in World War I. Farther west, in Pasadena, Calif., Chicago White Sox pitchers warmed up for games by chucking fastballs through a cardboard caricature of a leering, bucktoothed Japanese soldier. Meanwhile, the Sporting News urged that major league baseball somehow “withdraw from Japan the gift of baseball which we made to that misguided and ill-begotten country.” While acknowledging that the sport was wildly popular in Japan, the magazine conjectured that the true meaning of baseball had never really caught on in the island nation. “They may have acquired a little skill at the game, but the soul of our National Game never touched them,” publisher J.G. Taylor Spink wrote dismissively. “No nation which has had as intimate contact with baseball as the Japanese could have committed the infamous deed of the early morning of December 7, 1941, if the spirit of the game ever had penetrated their yellow hides.” Japan, for its part, outlawed baseball as an insidious American influence on its time-honored culture.

Despite such outward trappings as a newly stitched flag insignia on all players’ uniforms and the required playing of “The Star-Spangled Banner” before all home games, the 1942 baseball season was not greatly affected by the onset of the war. Few major league players were called up that first year, and the overall quality of play did not suffer noticeably. While the United States Navy was decisively defeating the Japanese at the naval battles of the Coral Sea and Midway, and American marines were landing on the island stronghold of Guadalcanal, baseball went about its morale-boosting business. The New York Yankees, as expected, repeated as American League champions, while the St. Louis Cardinals, with the help a well-stocked minor league farm system directed by general manager Branch Rickey, surprised the defending champion Brooklyn Dodgers to win the National League pennant by two games. In the ensuing World Series, which the British Broadcasting System beamed to American servicemen stationed in Ireland and England, the upstart Cardinals spotted the Yankees the first game of the Series, then swept the next four games in a row, including two complete-game victories by rookie righthander Johnny Beazley from Nashville, Tennessee. Another prized rookie, Stan Musial, batted .315 for the Cardinals in 1942, the start of a storied Hall of Fame career for the Donora, Pennsylvania, native.

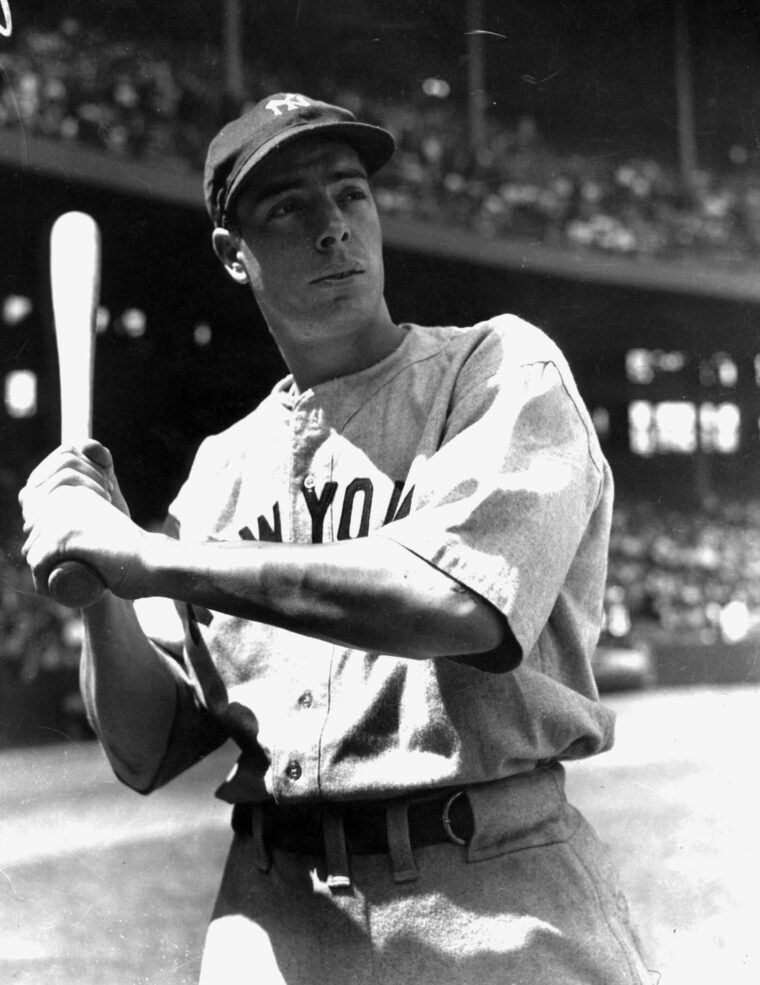

Musial was a notably healthy 23-year-old, but he was also married, with a son, and was the primary financial support for his parents (his father was a retired coal miner who suffered from black lung disease). In the off-season, Musial worked in a war-related assembly plant. As the 1943 season began, he remained undrafted, but the same could not be said for dozens of other talented major league players. Musial’s own Cardinals lost starting outfielders Terry Moore and Enos Slaughter and ace pitcher Johnny Beazley. Their World Series opponents the year before, the New York Yankees, lost superstar Joe DiMaggio, outfielder Tommy Henrich, shortstop Phil Rizzuto, first baseman Buddy Hassett, and pitcher Red Ruffing, who was taken by the Army despite being 38 years old, missing four toes from one foot, and supporting a wife, several children, and a mother-in-law at home.

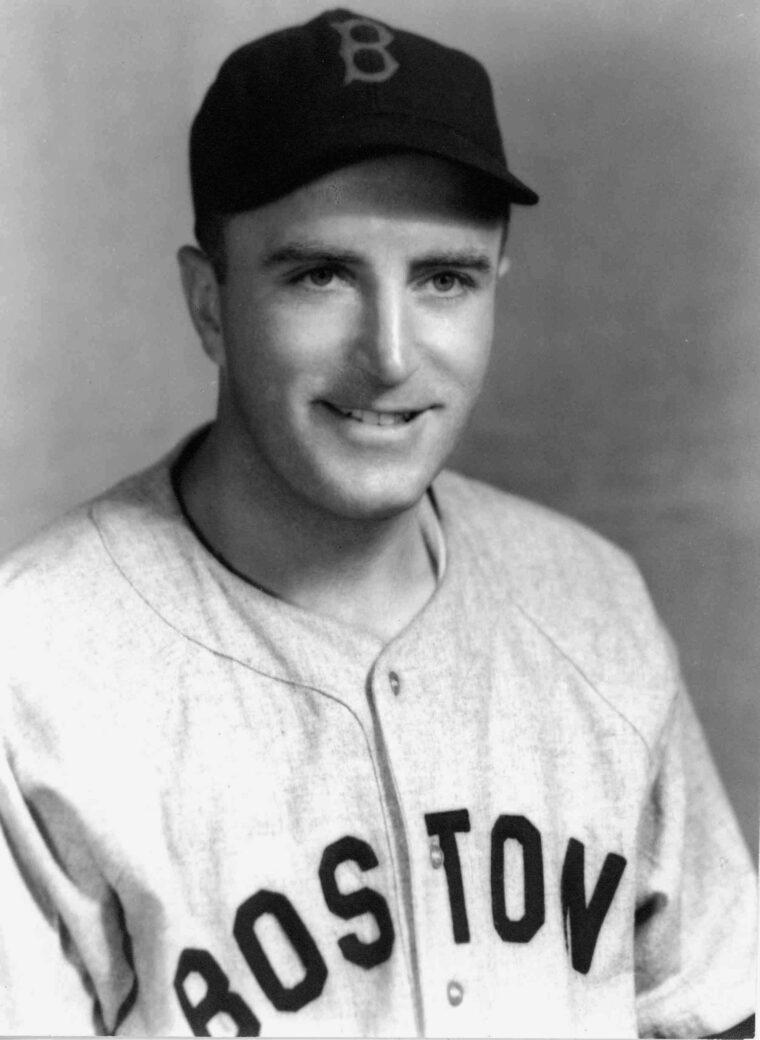

Other star players entering the armed services prior to the 1943 season included Ted Williams and Johnny Pesky, both of the Boston Red Sox, Johnny Mize of the New York Giants, Johnny Sain of the Boston Braves, Bob Lemon of the Cleveland Indians, and Charlie Gehringer of the Detroit Tigers.

The two biggest names on that list, of course, were Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams. Both men had been widely criticized for accepting exemptions the previous season. New York Times sports editor M.M. Caretti complained in a scathing column: “It seems to me that men well known in sport should take the lead in volunteering for their country in time of need and not wait to be drafted, much less accept exemption.” Williams, who won the Triple Crown in 1942 after hitting .406 in 1941, rejected the criticism. “I have as much right to be exempted as anybody else,” he said. “I have my mother to support. Before my status was changed to 1-A, I made commitments which I must go through with. I can do so by playing ball this year [1942]. When the season is over, I’ll get into the Navy as fast as I can.”

Williams made good on his promise, entering the Navy and training as a pilot. DiMaggio, likewise, enlisted in the service in early 1943—in his case, the Army. Miffed at being offered a pay cut by the Yankees, the star centerfielder did not even bother to notify the club of his enlistment.

In all, some 219 major league players were members of the armed services in 1943, along with hundreds of topnotch minor league players, necessitating a frantic search by teams for adequate frontline replacements. Old-time stars such as former Pittsburgh Pirate outfielder Paul Waner, now a glasses-wearing 40-year-old, were brought back to the big leagues for another tour of duty, and journeymen players like Oris Hockett of the Indians and Nick Etten of the Yankees suddenly found themselves stars for the first time in their careers.

The manpower shortage was so severe that Chicago Cubs general manager James T. Gallagher proposed that the clubs pool their remaining players to create more parity among teams, a suggestion that St. Louis Cardinals owner Sam Breadon called “unthinkable, unworkable … an offspring of socialism that has no business in baseball.” Instead, Breadon, a committed capitalist, ran a two-column want ad in the Sporting News under the headline: “Cardinal Organization Needs Players.”

For his part, Yankees’ general manager Ed Barrow made public a letter he had received recently from a fan. “I am ready to play left field for the Yankees,” the note read. “I am a fine fielder and a good hitter and could easily make good. I also am free from draft or war work call. I have a recent discharge from the state hospital for the insane at West Haven, Connecticut.” Barrow turned down the offer, but allowed that if the man had still been confined to the insane asylum in West Haven, “I would write him to move over. The situation in baseball is enough to drive anybody daffy.”

McCarthy Added Patriotically That the Team was Willing to “Do All in Our Power to Cooperate with the War Effort”

Adding to the daffiness was a decision by baseball commissioner Landis to require the major league teams to forego their annual spring training sessions in Florida and California. Instead, as part of a nationwide move to curtail train travel for all non-essential individuals, Landis ordered 14 of the 16 big- league teams to hold spring training in an area east of the Mississippi River and north of the Ohio and Potomac rivers. The two St. Louis clubs, the Cardinals and the Browns, were allowed to continue training near their homes. The decision led to a number of ridiculous sights. Dodger players arrived on skis for spring training at the Catskills resort of Bear Mountain, New York, where they found the local groundskeeper hard at work building a fire at first base. The Boston Braves made camp at the exclusive Choate School in Wallingford, Conn., where they bedded down in vacant dormitories—the students were away on spring break—and manager Casey Stengel, nicknamed “the Ol’ Professor,” obligingly conducted drills in a site-appropriate cap and gown.

The New York Giants set up camp on the former estate of tycoon John D. Rockefeller in Lakewood, New Jersey, playing their games on a ballfield carved out of the oil baron’s private nine-hole golf course. Other teams trained indoors at school gymnasiums or local Army bases, and Chicago White Sox pitchers sometimes warmed up inside their hotel ballroom at French Lick, Indiana, propping mattresses against the walls as backstops.

The cold weather outside and the limited space indoors induced some teams to hire special physical fitness instructors to help their players get ready for the upcoming season. The Cincinnati Reds’ instructor, Bill Miller, raised eyebrows when he had players at the Indiana University spring training camp warm up to rhumba music provided by Tommy de la Cruz, a Cuban-born pitcher whose brother sang with Xavier Cugat’s Latin band. Passing soldiers en route to their own physical fitness programs at the university gave the gyrating players a long, loud horselaugh as they passed. The training session was not completely wasted for the Reds, however, as they signed a hulking IU student named Ted Kluszewski to a minor league contract. After the war, “Big Klu” would become a fixture at first base for the Reds for the next decade and a half.

Baseball executives worried that the unconventional training conditions would leave players unprepared for the rigors of the regular season. Yankees manager Joe McCarthy complained, “the sport is essentially an outdoor one and indoor training is of little help.” McCarthy added patriotically that the team was willing to “do all in our power to cooperate with the war effort,” and asked reporters not to construe his remarks as “any sort of beef.”

Chicago Cubs manager Jimmy Wilson was less diplomatic. “Calisthenics stink as a baseball conditioner,” he said. “A player goes through all those monotonous drills and when he gets through he’s sore all over. He has exercised muscles he never knew he had, muscles that won’t help him one bit when he’s out there in a game.” The chilly conditions also contributed to several players getting severe colds before the season got underway. “An awful lot of us got sick there,” St. Louis Cardinals outfielder Danny Litwhiler recalled of the team’s makeshift camp on eastern bank of the Mississippi River at Cairo, Illinois.

“It was just so damp and so cold there,” Detroit Tigers pitcher Virgil Trucks, describing the Tigers’ camp at Evansville, Indiana, summing up the unique spring training experience for all big league players. “It was quite cool, it was always wet, it wasn’t anywhere near like Florida weather, but you could train, you could do running,” Trucks said. “It wasn’t an ideal area for spring training, but since the circumstances called for that, nobody complained about it. We all went about our jobs.”

Once the regular season got under way in 1943, the players faced an additional challenge, one that made Trucks’ and other pitchers’ jobs much easier—a newly designed baseball, the much-derided “balata ball.”

The new ball was made necessary by the Japanese seizure of key rubber producing plantations in Malaya and the Dutch East Indies, which forced the government to ration existing rubber supplies for use in the construction of tanks and airplanes. The A.G. Spalding Company, which had made every major league baseball since 1877, went through 16 different variations before coming up with a new design that replaced the traditional cork-and-rubber center of the ball with a center composed of two layers of balata, a hard rubbery substance made from tropical trees and ordinarily used in golf ball covers and telephone cable insulation. The new ball was noticeably less lively than regular baseballs—tests conducted by the Cooper Union Institute of Technology found the balata ball to be 25.9 percent less resilient than a regulation 1942 baseball. Players did not need scientific tests to tell them what they could see with their own eyes.

“The ball wouldn’t ride,” said Cincinnati Reds first baseman Frank McCormick. “If you hit it on the end of the bat, or even if you got good wood on it, it felt like you had a handful of bees. It was like hitting a piece of concrete.” Stan Musial, watching his best drives fall several feet short of the fences, said the experience made him understand what it must have been like to play during the deadball era, before Babe Ruth ushered in the dawn of the tape-measure home run.

With the help of the new balata ball, big league pitchers threw 11 shutouts in the first 29 games of the season, and no home runs at all were hit in the first 11 games. Detroit Tigers manager Steve O’Neill, who had played as a catcher with the Cleveland Indians during the first two decades of the century, observed sourly, “any ball club would be lucky to get two runs in a game with this new ball. It’s deader than the one in use when I was playing.” And Cincinnati Reds owner Warren Giles, watching the Reds and the Indians get a grand total of one extra-base hit in 21 innings of spring training play, grumbled that the baseballs made by Spalding had used “ground-up bologna instead of balata and cork.”

Making a suitably martial analogy, Giles complained that “asking big leaguers to play with the sort of ball with which we are opening the season would be like asking our soldiers, sailors, and marines to win the war with blanks instead of real ammunition.”

National League President Ford Frick was so alarmed by the lack of offense that he ordered Senior Circuit teams to play with leftover 1942 baseballs until they were used up. “Baseball faces a tough enough year as it is, without continuing play with a dead ball and thus alienating the spectators,” Frick said. “You can imagine the fans’ reaction to going to a game and watching well-hit balls plop feebly into fielders’ hands.” Stung by the protests, Spalding hastily redesigned the balata ball, replacing the center with unhardened rubber cement. The first day the new ball was used, six homer runs were hit as opposed to only nine home runs in the first 72 games of the season.

Along with the new ball and bats made from inferior quality wood, major league players had to contend with such familiar homefront viscidities as stadium dim-outs during air-raid drills, food rationing, room shortages, and severely overcrowded passenger trains. Players accustomed to traveling in Pullman car luxury and dining nightly on T-bone steaks had to make do with sleeping on train benches and choking down a spartan menu of fish and macaroni. Soldiers traveling by train to their military bases had first dibs on sleeping accommodations and dining cars.

After Winning the Title, the Yankees Took Full Advantage of Draft-Exemption Loopholes

Many players’ wives went on voluntary diets to save their ration cards for their husbands. “They kept fit and we ate good,” Philadelphia Phillies outfielder Danny Litwhiler remembered somewhat unchivalrously. The crosstown Philadelphia Athletics had it slightly better. Third-string catcher Tony Parisse’s father owned a meat market three blocks from Shibe Park, and players’ wives could shop there more freely than they could at other tightly rationed stores.

Owing in part to their vast farm systems, and in part to the number of superb players they still retained—for one more year, at least—the Yankees and Cardinals repeated as league champions in 1943. Travel limitations mandated that the first three games of the World Series would be played in New York, the remaining games in St. Louis. As it was, there were only two games played in St. Louis, with the Yankees closing out the series, four games to one, to avenge their 1942 defeat.

In winning the title, the Yankees took full advantage of draft-exemption loopholes. Only two Yankee players were bachelors in 1943, pitcher Atley Donald, who was 4-F due to a variety of eye and back problems, and infielder George “Snuffy” Stirnweiss, who was the sole support of his mother and sister and also suffered from a stomach ulcer. Midway through the season, the Yankees sold second baseman Gerry Priddy to the Washington Senators primarily because, although he was married, he had no children and thus was prime draft material.

Such considerations entered into the thinking of all the major league clubs, with 4-F players who could actually play being more highly coveted than draftable players. Three of the best of the 4-Fs were Cleveland shortstop Lou Boudreau, who suffered from heel spurs; St. Louis Browns shortstop Vern Stephens, who had allergies; and Detroit pitcher Hal Newhouser, who had a congenital heart murmur. All performed at a high level despite their handicaps—much to the displeasure of opposing fans whose own less athletically gifted sons were serving overseas in North Africa, Sicily, New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands.

By the spring of 1944, there were 12 million Americans under arms, including 340 major leaguers and over 3,000 minor leaguers. The defending champion Yankees were hit hardest of all. Before the regular season started, they lost regulars Billy Johnson, Charlie Keller, Joe Gordon, and Bill Dickey, plus pitcher Marius Russo and outfielder Roy Weatherly. In addition, ace relief pitcher Johnny Murphy had taken a job in a war plant, and general manager Ed Barrow would not allow him to pitch part-time.

“A man is either a major league player, or a war worker or bricklayer,” Barrow said. “I think that using part-timers would demean big league ball. It would give it a semi-pro tone.” Manager Joe McCarthy refused to name a starting lineup in the press, lamenting, “How could I possibly do that? I couldn’t tell you who will be here next Tuesday.” Chicago White Sox manager Jimmy Dykes had scant sympathy for his New York counterpart. “I feel sorry for that McCarthy,” he said sarcastically. “Now the poor guy will have to have a thought now and then instead of pressing a push-button every time he wants a DiMaggio or a Keller or a Gordon to hit a home run.”

With the war hitting a peak in Europe and the Pacific, the major league teams continued to lose players in 1944. Yet again, the two St. Louis contingents lost fewer than the rest. Stan Musial, the 1943 batting champion, retained his cushy deferment. He was joined by third baseman Whitey Kurowski, who was 4-F after a bout of childhood polio; pitcher Mort Cooper and shortstop Marty Marion, deferred with bad knees; and catcher Walker Cooper, who suffered from a variety of non-debilitating ailments.

The Cardinals’ longtime rival, the Brooklyn Dodgers, were not so lucky. They lost their last two starting infielders, second baseman Billy Herman and third baseman Arky Vaughn, and were reduced to using 16-year-old Tommy Brown and 17-year-old Eddie Miksis as a teenaged double play combination during the season. Even so, Brown and Miksis were older than Cincinnati Reds pitcher Joe Nuxhall, who was only 15 when he made his major league debut on June 10, 1944. Nuxhall pitched two-thirds of an inning against the Cardinals in a 19-0 blowout, giving up five runs on five walks, two singles and a wild pitch. It would be the lefthander’s last appearance in the major leagues until he was recalled from the minors in 1952, the true start to a solid professional career in which he would win 135 games and post a lifetime earned run average of 3.90.

Even luckier than the Cardinals were their longtime Sportsman’s Park roommates, the Browns, who entered the 1944 season with the oldest and most 4-F laden team in the American League—13 players in all, not counting catcher Frank Mancuso, who had already been honorably discharged. Capitalizing on their experience, the downtrodden Browns snared their first and only pennant by one game over the Hal Newhouser-led Detroit Tigers. Unlike his counterpart on the New York Yankees, Browns general manager William DeWitt had no qualms about using part-time players. Pitcher Denny Galehouse won nine games for St. Louis in 1944 while working at a Goodyear aircraft plant in Akron, Ohio.

Typically, Galehouse would work all week building planes, then take an overnight train to whatever city the Browns were playing in that weekend. After pitching the first game of the traditional Sunday doubleheader, Galehouse would rush back to Akron to rejoin the assembly line on Monday. Another Browns player, outfielder Chet Laabs, worked at a Dodge factory in Detroit, making jeeps for the Army. With the help of his father-in-law, Browns’ manager William DeWitt, Laabs obtained a transfer to a St. Louis pipe plant, where he helped make pipes that were later used in the Oak Ridge, Tennessee, plant where the first atomic bombs were constructed. Laabs was available for home games and weekend trips to other midwestern cities. Although he never fully developed his batting eye in 1944, Laabs hit two home runs against the Yankees to clinch the pennant for St. Louis on the final day of the season. Reverting to form, the Browns lost the ensuing “Streetcar Series” to the Cardinals, four games to two, and soon receded into comfortable mediocrity before moving to Baltimore and becoming the Orioles in 1953.

That autumn Franklin Roosevelt was reelected to an unprecedented fourth term as president, and Allied forces drove eastward toward Germany and prepared to breach the Nazis’ supposedly impregnable Siegfried Line. Meanwhile, in the Far East, General Douglas MacArthur fulfilled his pledge to return to the Philippines, trudging through the surf at Leyte Gulf. With casualties rising, James F. Byrnes, head of the Office of War Mobilization and Reconversion, sent a letter to General Lewis B. Hershey, director of the Selective Service, urging that professional athletes with medical discharges be recalled to military service and that players holding 4-F exemptions be carefully reexamined.

“If Baseball has a Morale Value, it can be Just as Great Played in the Army. Let Those Fellows Play Their Baseball with the Japs and the Germans.”

“It is difficult for the public to understand, and certainly it is difficult for me to understand, how these men can be physically unfit for military service and yet be able to compete with the greatest athletes of the nation in games demanding physical fitness,” Byrnes wrote. “They prove to thousands by their great physical feats upon the football or baseball field that they are physically fit and as able to perform military service as are the 11 million men in uniform.”

Hershey agreed, directing local draft boards to take another look at the professional athletes under their authority. Roosevelt, too, got into the act, reiterating his call from the previous year for a national service act aimed at utilizing the country’s five million 4-Fs “in whatever capacity is best for the war effort.” Kentucky Congressman Andrew J. May, charged with drafting new “work or fight” legislation, was equally resolute. “Any man who is able to play baseball is able to fight or work in a war plant,” May said. “If baseball has a morale value, it can be just as great played in the Army. Let those fellows play their baseball with the Japs and the Germans.” No one had the nerve to point out that the sports-loving Nazis had never played baseball.

With more and more major leaguers being drafted into the service, the quality of play suffered noticeably during the 1945 season. A full 60 percent of the players on the last pre-war rosters four years earlier were now in the military, and sportswriters joked with some accuracy that the rosters of such service teams as the Great Lakes and Norfolk Naval Training Stations constituted a third major league. But while Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Stan Musial, Bob Feller, Phil Rizzuto, Pee Wee Reese, and dozens of other big league stars played for the military, the civilian leagues prepared to mount their last wartime season.

Teams took players wherever they could find them. Forty-six-year-old pitcher Hod Lisenbee, who had given up Babe Ruth’s 58th home run in 1927, toiled on the mound for the Cincinnati Reds alongside teammates Guy Bush, 43, and Boom-Boom Beck, 40. Eddie Basinski, a concert violinist with the Buffalo Philharmonic, traded his bow for a fielder’s glove as a shortstop for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Old-time stars such as Jimmy Foxx, Red Ruffing, and Babe Herman were pressed back into service, and Foxx, in particular, amazed fans by taking his turn on the mound as well as at the plate, appearing in nine games, winning one and losing none, with a sparkling earned run average of 1.59.

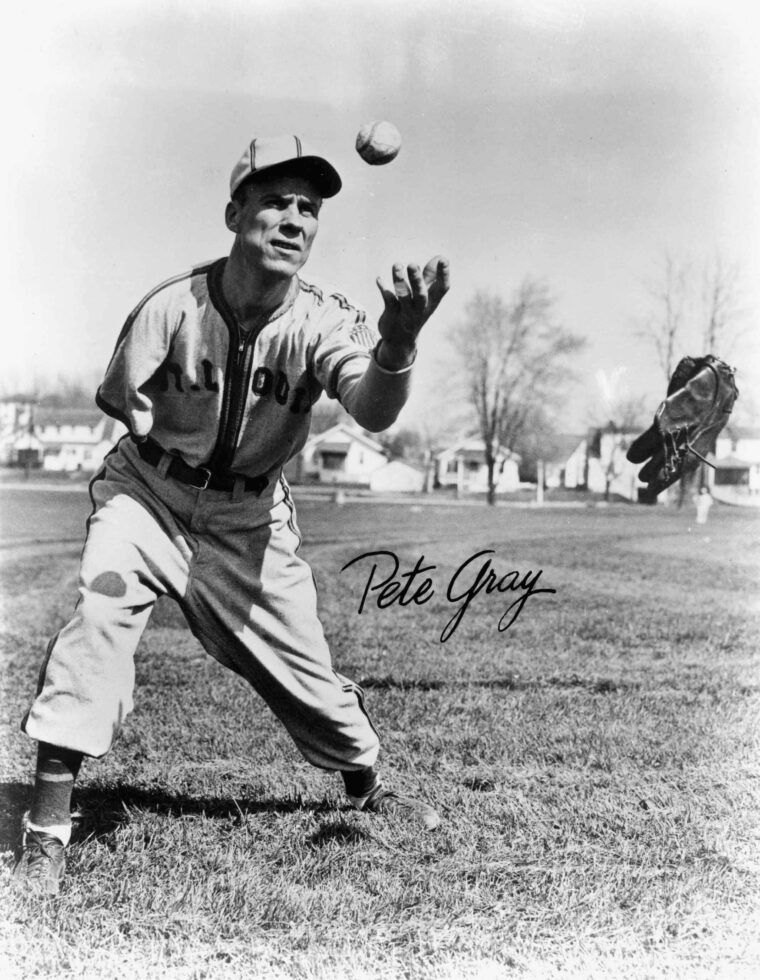

No one better symbolized baseball in 1945—and indeed all the war years—than St. Louis Browns outfielder Pete Gray. It is his photo that adorns the covers of various books devoted to World War II baseball, and he has a secure place in baseball history in general. Gray’s fame has nothing to do with his lifetime batting average of .218, his 13 career-total runs batted in, his six doubles and two triples. His notoriety is based, instead, on the simple fact that he played in 61 major league games with only one arm (he had lost the other in a childhood farming accident).

Gray’s brief stint in the big leagues was more a publicity stunt than a true indication of his abilities, and his teammates on the Browns bitterly resented his presence on the team. Former starting centerfielder Mike Kreevich abruptly quit midway through the season, declaring, “If I’m not playing well enough so that a one-armed man can take my job, I quit.” Teammates estimated, perhaps unfairly, that Gray personally cost them eight to 10 games in 1945, enough to give the pennant to the Detroit Tigers by a six-game margin. The Tigers, in turn, were sparked by star Hank Greenberg’s unexpected return to the team in July, after more than four years in the Army. Greenberg homered in his first game against the Philadelphia Athletics and won the pennant with a dramatic grand slam home run against the Washington Senators on the last day of the season. The Tigers went on to defeat the Chicago Cubs in the 1945 World Series, the last time the Cubs have appeared in the Series.

Gray’s brief duty with the Browns and Greenberg’s 11th-hour return to the Tigers highlighted baseball’s final wartime season. By the time the season was over, President Roosevelt had died, the Germans and the Japanese had surrendered—the latter only after forcing the United States to drop two devastating atomic bombs on their homeland—and the Allies had persevered to a gallant if exhausting triumph. Baseball had done its part, sending thousands of players into the armed forces, while carrying on as best it could with rosters dotted with ancient mariners, service rejects, beardless teenagers and a one-armed man.

In the end, only two major league players were killed in World War II, Washington Senators outfielder Elmer Gedeon, who died in France on April 14, 1944, and Philadelphia A’s catcher Harry O’Neill, who was killed at Iwo Jima on March 6, 1945. Fifty-seven minor leaguers also gave their lives.

Dozens of major leaguers, including such reigning superstars as Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Hank Greenberg and Bob Feller, lost at least three years of playing time in the prime of their careers. If they ever regretted their military service, none of them said so publicly. World War II, after all, had been “the good war,” and baseball and its players, at home and abroad, had helped to fight and win the good fight. Some victories never show up in the box scores.

Roy Morris Jr. is the editor of Military Heritage magazine and the author of several well-received books. He resides in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments