By Michael D. Hull

None of the Allied services engaged in World War II was in action longer or suffered a higher percentage of casualties than the British Merchant Navy.

The unsung heroes who plied the world’s sea-lanes under the Red Ensign, nicknamed the “Red Duster,” were on the front lines from beginning to end. Their war began less than nine hours after Great Britain and France declared war on Nazi Germany on September 3, 1939, following the invasion of Poland.

The Perilous Atlantic Crossing

At 7:45 that fateful Sunday evening, the 13,000-ton liner Athenia of the Donaldson Atlantic Line was on course from Belfast, Ireland, to Montreal, Canada, with 1,418 passengers—men, women, and children. They included 316 American citizens. Zigzagging at 10 knots, the Athenia was steaming 250 miles west of Inishtrahull, Donegal, when she was torpedoed without warning by the German submarine U-30, commanded by Lieutenant Fritz Lemp.

The liner stayed afloat until early the next morning, by which time two Royal Navy destroyers, a Norwegian freighter, an American steamer, and a motor yacht had arrived to rescue the survivors. Eighty-three civilian passengers, including 22 Americans, perished in the sinking. The 18 crew members who died were the first Merchant Navy casualties of the war.

The first two weeks of the war saw 27 British merchant ships go down, and between September 3 and the end of the year, 215 merchantmen totaling 748,000 tons were lost. Yet, by the end of 1939, more than 5,500 convoyed Allied vessels had reached their destinations. In the first year of the war, 438 merchant ships were lost.

During the six years of hostilities between the Allies and the Axis powers, the war at sea never ceased. Late in the evening of May 7, 1945, the day of Germany’s unconditional surrender and the day before VE-Day, Kapitanleutnant Emil Klusmeier, commanding a new Type XXIII U-boat, sighted one last Allied convoy sailing out of Edinburgh, Scotland, into the Pentland Firth. All aboard the merchantmen were rejoicing over the end of the European war as the submarine skipper—in disobedience of German Navy orders—fired his torpedoes into the Canadian steamer Avondale Park and the old Norwegian tramp steamer Sneland I. Twenty-three seamen were killed.

Klusmeier was out of order; Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz had ordered all of his U-boats to cease fire and surrender. Thus, the German submarine service ended the war the way it had begun it, with the destruction of defenseless ships.

12 Million Tons Lost

The stormy years from 1939 to 1945 saw the loss of almost 2,500 British merchantmen and 116 fishing vessels, amounting to about 12 million tons. A further 900 craft were damaged by enemy action. Great Britain began the war with almost 9,000 merchantmen of all classes, amounting to 21 million tons. These were vessels sailing under the British flag and those on British, Commonwealth, Indian, Panamanian, or colonial registers, together with chartered or requisitioned foreign ships.

From the start of the war, the German Navy sought with every means at its disposal to destroy enough merchant shipping to starve the British and force them out of the conflict, as it had come close to doing in World War I. German surface warships, supported by a network of supply craft and often disguised as merchantmen, were deployed as long-range commerce raiders, while most of Admiral Dönitz’s 46 operational U-boats roamed the ocean approaches to the British Isles.

Almost 32,000 of the 185,000 British merchant seamen who served during the war either went down with their ships, died subsequently as a result of the sinkings, were otherwise killed in action, or succumbed while prisoners of the enemy. The Merchant Navy lost proportionately more men than did any of the three British armed services (Army, Navy, and Air Force). Moreover, more than a few of the seamen lost were barely 16 years old, and some even younger.

From the beginning of March to the end of May 1941, U-boats sank 142 merchant ships, 99 of them British. Another 179 merchantmen were sunk by enemy aircraft, 44 by surface raiders, and 33 by mines. The tonnage lost in those three months exceeded the existing rate of British ship production three to one, and the combined Anglo-American production two to one. It was not until August 1942 that the Allies’ combined ship production at first balanced the losses and then commenced to exceed them as month followed month.

The worst month for the merchant service was December 1941, when 120 vessels were lost, 98 of them seized or sunk in the South China Sea when Japan entered the war. The worst year was from June 1940 to May 1941, when 806 merchantmen were lost at the rate of more than two a day. The majority of them fell victim to U-boats in the North Atlantic.

Starving the British Isles

![Kapit‰nleutnant Kretschmer wurde nach Versenkung von ¸ber 200.000 BRT feindlichen und dem Feinde nutzbaren Schiffsraumes als 6. U-Boots-Kommandant vom F¸hrer mit dem Eichenlaub zum Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes ausgezeichnet. Die Aufnahme entstand nach der R¸ckkehr von der erfolgreichen Feindfahrt auf der die 200.000 Tonnengrenze ¸berschritten wurde. PK-Tˆlle 1468-40 Nov[ember] 1940](https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/W-BritMerchant-10-HT-May10-186x300.jpg)

As in the latter half of World War I, U-boats created havoc for the British and other Allied merchant fleets. The fall of Norway and France in 1940 transformed the strategic situation in the Atlantic. From newly acquired bases, starting with Lorient on the Bay of Biscay, U-boats could threaten all shipping passing south of Ireland, while their range and endurance were greatly extended. No longer confined to operations within range of bases on the North Sea and Baltic coasts, Dönitz’s lethal boats could now patrol for days far out in the mid-Atlantic.

In August 1940, Adolf Hitler ordered that the submarines set up a total blockade of the British Isles, freeing them to attack any merchant vessel approaching or entering British waters. The following month, Dönitz’s undersea fleet started using “wolf pack” tactics, with about 20 U-boats making mass attacks on single convoys.

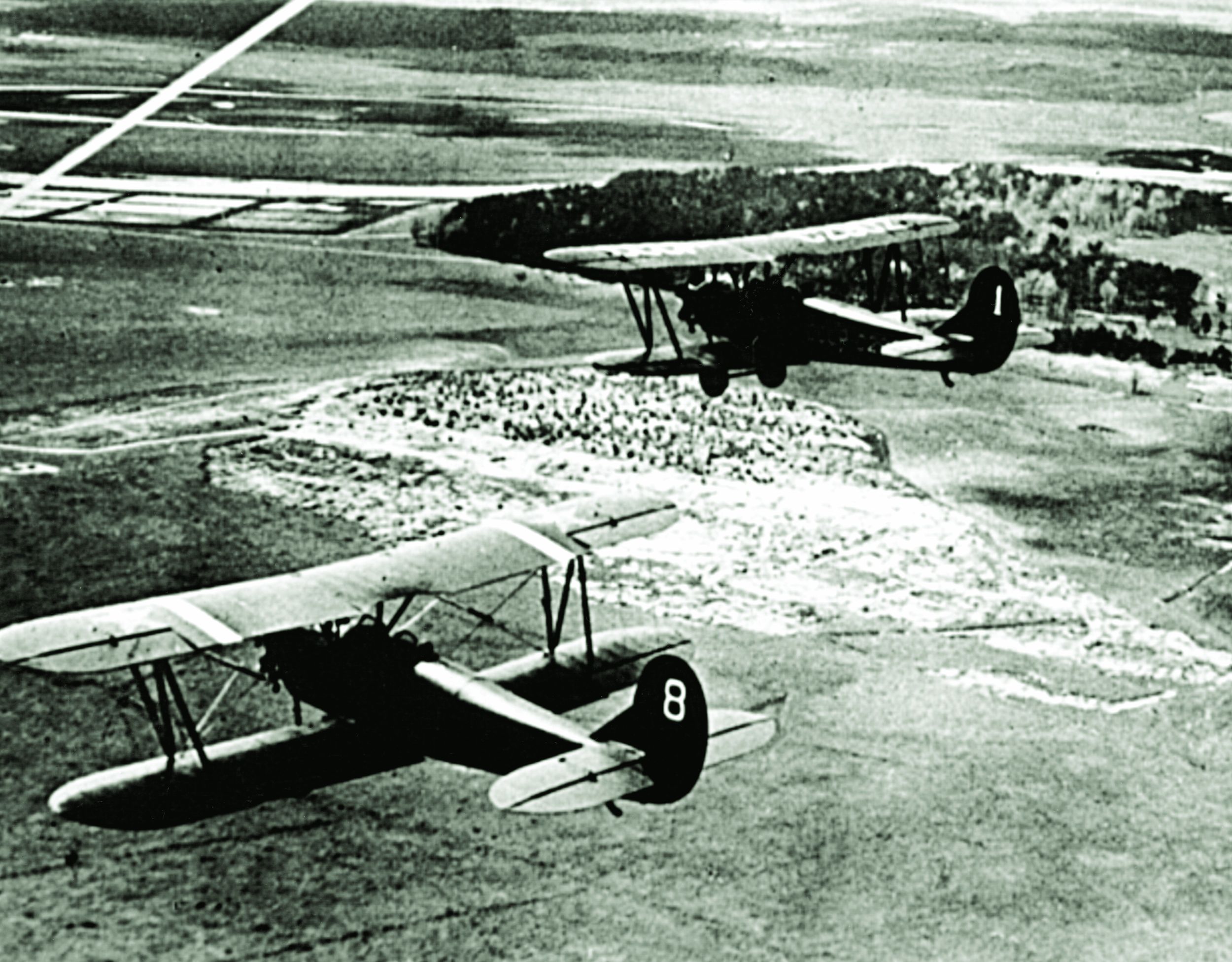

The same tactical flexibility was accorded the Kriegsmarine’s surface fleet, which was augmented by disguised auxiliary cruisers. At the same time, long-range Focke-Wulf 200 Condor reconnaissance bombers were used for missions over even the far northwestern approaches to the British Isles. The perils faced by Allied merchantmen and their escorts mounted.

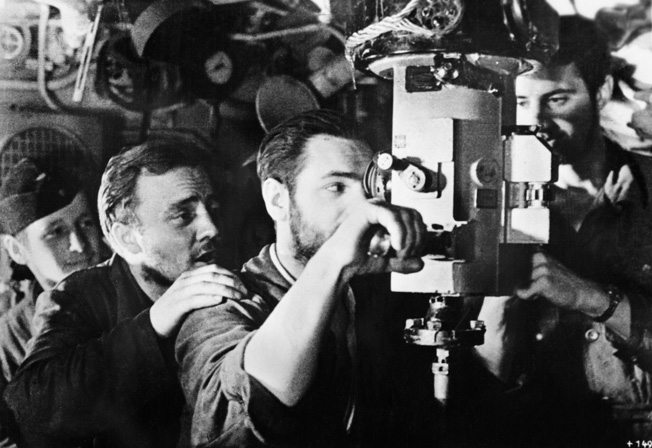

But the most dire threat came always from the U-boats, as exemplified by Otto Kretschmer, one of Germany’s ace submarine captains. Prowling in U-23 and later U-99 during 16 patrols in the first year and a half of the war, he sank 44 ships totaling 266,029 tons. For every day he spent at sea in that period, Kretschmer dispatched 1,000 tons of Allied shipping to the bottom, a record not equaled. Instead of firing salvos of four or six torpedoes from about 3,000 yards, Kretschmer preferred to act like a sniper, picking off individual ships at close range.

Yet, Kretschmer was chivalrous to his victims, sometimes providing the occupants of lifeboats with food, water, and course directions. Fortunately for the Allied seamen, however, U-99 was sunk by the destroyer HMS Walker in March 1941. Kretschmer and all but three of his crew were picked up and then interned in Canada.

“Happy Time” for the U-boats

Allied losses soared as the war progressed, and almost three million tons of shipping were destroyed between June and December 1940. During their “happy time” between July and October that year, U-boat crews in the Atlantic sank 217 ships for the loss of only two boats. Although surface warships, disguised raiders, aircraft, and mines all accounted for significant tonnage, German submarines claimed the lion’s share of losses to Allied shipping. Dönitz achieved this with only about 16 U-boats on station in the Atlantic at any given time. He pressed Hitler for more boats and for cooperation from a reluctant Luftwaffe. Dönitz dreamed of a fleet of 300 long-range submarines—with a third of them on station, a third going out or returning, and a third being re-equipped at base. But, fortunately for Britain, his demands were never fully met.

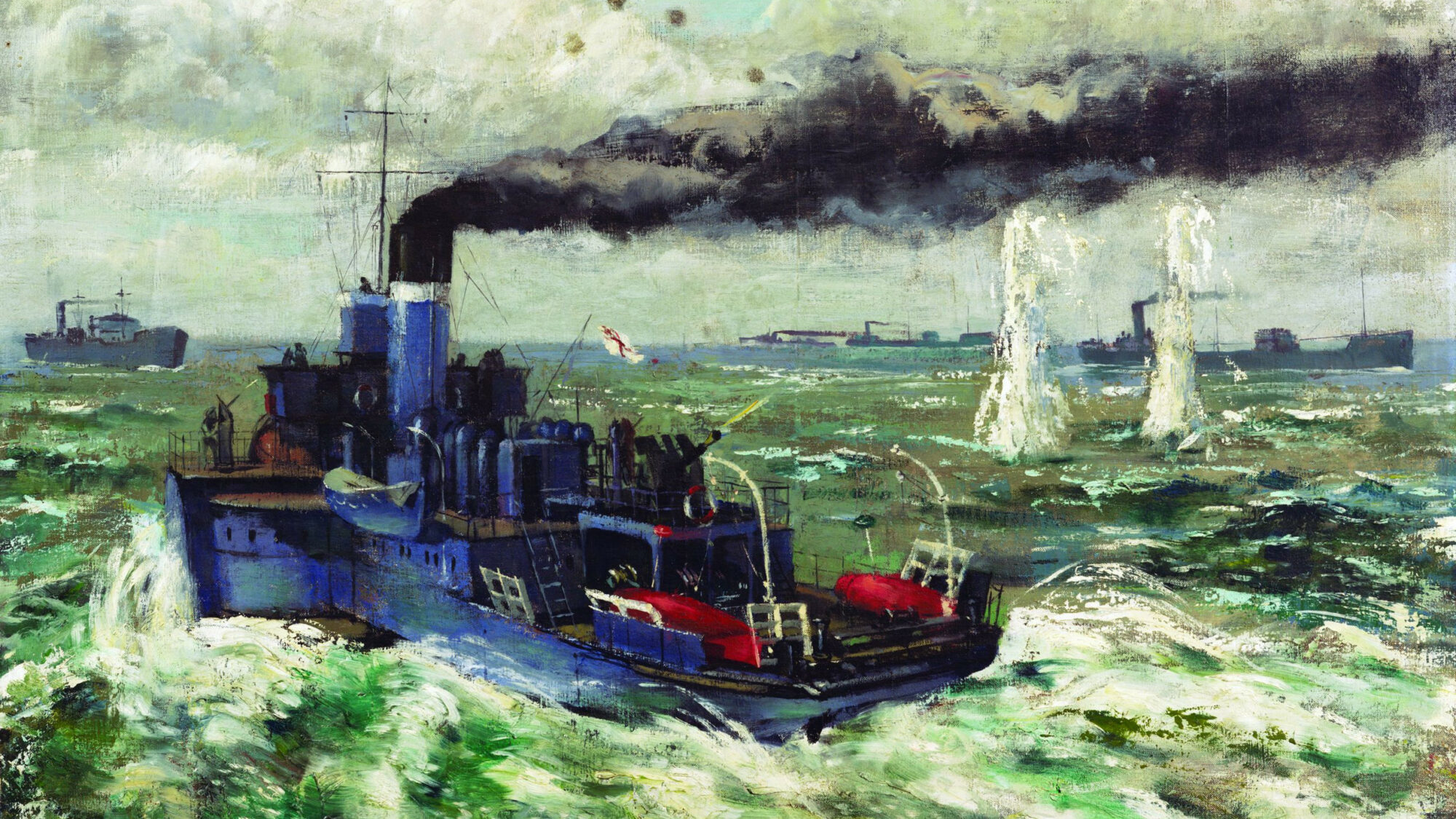

As the prospect of a German invasion of England receded after the Battle of Britain in 1940, more Royal Navy escort ships—destroyers, frigates, corvettes, sloops, and armed trawlers—became available and the British responses were better coordinated. Western Approaches Command was established at Liverpool and the Newfoundland Escort Force at St. John’s. The German Condor menace was reduced by the development of catapult-aircraft-equipped merchant ships and escort carriers.

But before adequate air cover and better defensive and detection measures could come into play, the Allied convoys remained intensely vulnerable. The first to have an escort through its entire voyage was Convoy HX-129, which crossed the Atlantic late in May 1941. During that year, the U-boats sank a total of 875 Allied ships (3,295,000 tons) in the Atlantic. By the first few months of that year, German submarine production steadily increased, with U-boats emerging from the shipyards at the rate of 10 a month. Their operational strength increased fourfold.

Dönitz’s fleet had grown to 331 boats in January 1942. By November, there were 42 U-boats deployed between Greenland and the Portuguese Azores, and 39 were active elsewhere in the Atlantic. After September 1941, when U.S. Navy ships started escorting convoys from a point 400 miles west of Iceland, Admiral Dönitz became increasingly frustrated and transferred his attention to the western coast of Africa. When America entered the war, he concentrated his efforts in the Western Atlantic, the Caribbean, and the Gulf of Mexico, and the result was a second “happy time” for the U-boat crews.

Dönitz’s undersea hunters sank 65 vessels in February 1942, 86 that March, 69 in April, and 111 in May. Total Allied losses for the year reached 1,664 ships, of which 1,160 were destroyed by U-boats. Many of the merchantmen were sunk in the first half of 1942 by U-boats roaming within sight of the American East Coast. Silhouetted against city lights along the New York and New Jersey shore, the merchantmen were sitting ducks for the German submariners.

U-boat offensive power reached its peak from January 1942 to March 1943. The United States finally adopted the convoy system and initiated blackouts along the Eastern Seaboard. In July 1942, all German submarines operating off the East Coast were redeployed to concentrate on traffic in the North Atlantic.

Eighty-Percent Losses

The year 1943 opened disastrously for the Allies, with Dönitz’s wolf packs sinking 203,000 tons of shipping in January, 359,000 tons in February, and 627,000 tons in March. This was twice the rate of Allied merchant ship construction, and for every U-boat sunk two were launched. Admiral Dönitz became commander in chief of the Kriegsmarine early in 1943 while retaining direct control of the U-boat force. The surface fleet had by now lost favor with Hitler, and submarine construction was given full priority.

The Battle of the North Atlantic reached its climax in May 1943 when Dönitz lost 41 submarines, making a total of 114 for the first five months of the year. By that July, the number of U-boats had begun to fall, and the tonnage of Allied merchantmen launched exceeded that lost for the first time in the war. Dönitz conceded that he was losing the struggle but refused to give up.

U-boats were equipped with schnorkel systems, which enabled them to run submerged while recharging their batteries, and their antiaircraft armament was augmented. And more sophisticated, powerful submarines were being developed. But the losses of operational U-boats at the hands of British, Canadian, and American naval and air units continued to mount, while the monthly sinkings of Allied ships diminished, only once exceeding 100,000 tons for the rest of the war. Meanwhile, Allied countermeasures—more convoy escorts; improved radar and sound detection equipment; new depth charges, rockets, and forward-throwing mortars; and extended air cover—had been deployed just in time to stave off defeat.

American-built, long-range Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers closed the air-cover gap in the mid-Atlantic, and big Short Sunderland flying boats of Royal Air Force Coastal Command ranged far out to shepherd the merchant convoys coming and going. There was now tighter protection for the convoys, and losses dropped dramatically. The merchant seamen could now breathe more easily.

The long, bitter Battle of the Atlantic proved costly for both the Royal Merchant Navy and Dönitz’s submarine force—785 U-boats sunk and 11,899,732 tons of shipping (2,232 vessels) lost. Eighty percent of all operational U-boats were sunk, with their crews suffering the highest percentage of fatalities among the German armed services.

Half the World’s Maritime Fleet

Britain entered the war as the premier maritime country, with about 50 percent of the world’s shipping tonnage under her flag. But, as with the other British armed services, the outbreak of war caught the Merchant Navy largely unprepared. It had suffered grievously from years of depression since World War I. Rivers and lochs were choked with laid-up, rusting ships, and many seamen had left the service. In some years, the loss in manpower exceeded 15,000.

In 1938, when a handful of unblinkered men in Whitehall saw the ominous portents of war in Europe, a register was compiled of volunteers ready to return to sea should the need arise. It was just as well that the precaution was taken. When war came in September 1939, about 12,000 serving merchant officers and men went at once into the Royal Navy. They were either in the Royal Navy Reserve; were serving in ships that became armed merchant cruisers, such as the Jervis Bay; or, in the case of the fishing fleet, were manning trawlers that were requisitioned as minesweepers.

The Navy, Britain’s long-established first line of defense, was stretched thin across the oceans and had to have manpower priority. But the Admiralty’s demand for officers in particular was such that it caused the Board of Trade—then responsible for the Merchant Navy—to urge a slowdown in the transfer of seamen into the Navy until the already depleted ranks could be made up.

Taken over by the Admiralty in August 1939, the Merchant Navy faced an immense and vital task in the war years. Yet, in the critical months of 1942 it numbered only about 120,000 officers and men. This number was small in comparison with the Royal Navy, for a merchant ship requires only a fraction of the complement necessary to man a warship. However, the total number of merchantmen vastly exceeded the number of fighting ships.

The Convoy System

To meet the U-boat threat, the Admiralty introduced a convoy system in the Western Approaches soon after the outbreak of war, and this was gradually extended to cover most major Atlantic shipping routes. By 1943, Atlantic convoy lanes formed a huge interlocking pattern. Linked to it was the convoy route through the Indian Ocean, from the Cape of Good Hope to the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, though in general most vessels traversing the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean were expected to sail singly.

On every ocean and every sea, from the Mediterranean to the Arctic, and from the North Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, British merchant ships formed the principal lifeline of the empire and its allies. The vessels were often required to carry cargoes for which they had not been built across oceans they had never been meant to sail. They traveled to and from Halifax and Liverpool, Cape Breton Island and Glasgow, Freetown and Valletta, Suez and Tobruk, Algiers and Casablanca, Reykjavik and Murmansk, and Rangoon and Singapore.

In any given period of the war, up to a dozen convoys were traversing the Atlantic, each numbering between 10 and 100 ships. Some were bound for Britain with vital war supplies, and others were heading outbound in ballast to collect the next consignment. The commercial fleets comprised many types of craft—fast and slow, large and small, old and new, coal-fired and oil-fired—manned by men of widely different nationalities, backgrounds, and faiths.

The bulk of the Merchant Navy’s sailors hailed from Merseyside, Clydeside, Newcastle, Hull, London, South Wales, and the English West Country, which had bred hardy mariners since the time of Drake and Raleigh. Many others were Lascars from India, West Indians, Chinese from Hong Kong, Somalis from Africa, Irishmen from Eire, Arabs from various parts of the British Empire, men from the Dominions, Jews from Britain and other lands, and citizens of enemy-occupied countries who had found themselves cut off in Britain or had escaped there.

Some Americans also served in the Merchant Navy. The best known was Richard Maury, a descendant of Matthew Fontaine Maury, the famed U.S. naval hydrographer and oceanographer, who joined the British service in 1940. He served until the Pearl Harbor attack, when he transferred to the U.S. Merchant Marine and helped to train crews in Canada.

Transporting and Evacuating Troops

Throughout the war, even after America’s entry, the British Merchant Navy served as the main conduit for Allied troops, tanks, aircraft, weapons, spare parts, oil, food supplies, and essential related matériel in every theater of operations except the Pacific, where the U.S. Merchant Marine played the predominant role. From September 1939 to June 1940, ships flying the Red Duster transported the British Expeditionary Force—with all of its tanks, guns, trucks, and other equipment—to northern France. Merchantmen kept the BEF supplied, often under fire, yet only one ship was lost during those nine months. The so-called Phony War was real for Britain’s seamen.

Along with Royal Navy units, merchant ships took part in several troop evacuations during the grim early years of the war when Britain suffered a string of defeats, from Norway to the Aegean. During Admiral Bertram Ramsay’s brilliant Operation Dynamo in May-June 1940, the Merchant Navy played a crucial role, with 36 prewar ferries, seven hospital carriers, three store ships, tugs, trawlers, and even cockle boats picking up British and French troops from the burning beaches of Dunkirk.

Merchantmen also took part in the costly evacuations from Greece and Crete in April-May 1941; the Anglo-American amphibious landings in North Africa in November 1942, Sicily in July 1943, and Salerno, Italy, in September 1943; and the greatest invasion of all, Operation Overlord. Two thousand merchant ships—most of them British—supported the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, with losses of barely 1 percent.

Most troop movements during the war were made by British merchantmen and converted liners, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill said that the transatlantic crossings of the big, high-speed Cunard liners Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth—ferrying Canadian and American troops to Europe—shortened the war by two years. Each ship sailed independently and carried 12,000 men at a time. Between January and June 1944, a million U.S. Army personnel were ferried to Britain.

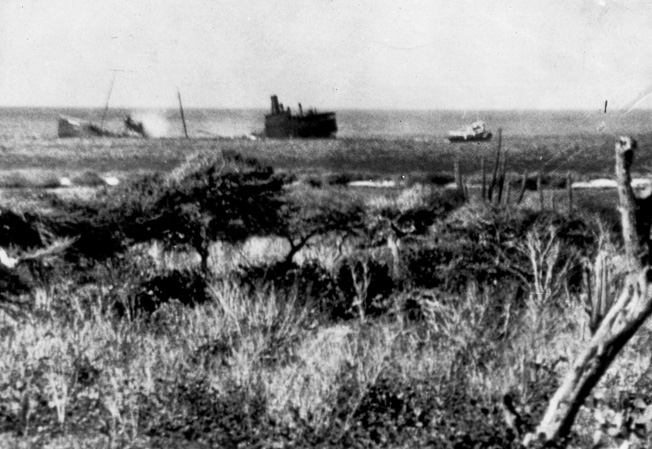

The survival of the strategic Mediterranean island bastion of Malta, bombed and besieged in 1940-1942, was credited to Royal Navy and Merchant Navy convoys that ran a relentless gauntlet of Axis air raiders and submarines. “The work which this magnificent service [the Merchant Navy] did, in conjunction with the Royal Navy, in bringing supplies to Malta cannot be overstated,” declared Sir William Dobbie, wartime governor of the island. “Without that help, Malta could not have held out…. The debt the empire owes to the Merchant Navy is immense.”

Life Under the Red Duster

Month after month through the war, in both fair and foul weather, the merchant ships and their crews plied back and forth, singly or in convoy. Day and night, lookouts and gun crews stood watch, eyes strained for black specks in the skies that could be enemy planes, and tirelessly scanned the waves for the telltale wake of a submarine periscope. It was harrowing, nerve-wracking duty as the seamen sailed on, living day by day and praying for a safe landfall.

At night, they lay in their bunks and hammocks trying to sleep but dreading the sudden thunder of explosions and clangor of bells that signaled a U-boat or air attack, injuries, breathless dashes to the lifeboats, or, at worst, a struggle to survive in frigid waters. Survivors of sinkings told of the fearful minutes between an explosion deep in the bowels of the ship and its final plunge to the bottom, the heartbreak of losing shipmates, and the frenzy of having to fight their way clear through twisted steel, scalding steam, and flames in a desperate effort to reach a lifeboat, sometimes only to find that it had been destroyed. When tankers were torpedoed, survivors who made it overboard found themselves struggling amid burning oil.

Even when in a lifeboat, the horrors were not yet over for seamen after their ships had gone down. Unless they were lucky enough to be picked up quickly by a shepherding destroyer or corvette, they watched helplessly as comrades died from injuries, exposure, or thirst. Many survivors crammed into lifeboats or clinging to rafts drifted in the ocean currents for days, weeks, and even months while their sparse rations and water dwindled. Then they tried to assuage gnawing hunger with raw fish or unsuspecting seagulls. Then there was the additional peril of being attacked by enemy vessels or planes. After sinking Allied merchantmen in the Pacific and other Far East waters, Japanese submarines regularly machine-gunned lifeboats and sometimes rammed them.

In the winter months, the merchant sailors endured snow, sleet, and raging mid-ocean storms as their heavily laden ships butted through towering waves and troughs. They shivered while scraping ice from decks, gun mounts, and superstructures, and then struggled to thaw out in cramped, fetid quarters below decks while off watch. Living conditions on the freighters, tramp steamers, tankers, and coasters were severely restricted and austere. Aboard a tramp steamer, only the master and chief engineer had cabins, with a toilet and bath; the deck officers shared cabins amidships below the bridge while the engineer officers’ quarters were above the engine room. The rest of the crew slept in two-tier iron-framed bunks below the forecastle head, not the most stable section of the ship. Firemen and greasers slept on the port side, and the seamen, boatswain, and carpenter on the starboard side. All had to queue up to use the head.

“It was the long Atlantic trips that were worst for cabin conditions,” reported one seaman, “especially on the lower decks, where the portholes couldn’t be opened. As many as eight men ate, slept, smoked, and broke wind, and generally lived in those ‘glory holes’ with their damp clothes. The air was thick and foul, like in a submarine. It was heaven to stand up on deck and breathe in the fresh air. There was no real recreation, only an occasional four hours on watch, eight hours off, with extra work like chipping, cleaning, and painting in off-duty hours. Any spare time was spent on private chores and sleep.”

The seamen sailing under the Red Duster during World War II earned every penny of their modest wages during long and perilous voyages. The pay for British merchant sailors was minimal, less than half that of their American counterparts. An able seaman earned 12 pounds a month, slightly more than half of that paid to a sergeant pilot in the RAF, and he had to provide himself with insurance.

The Arctic Convoys: Lifeline to the Soviet Union

Merchant ship duty was rigorous at all times during the war, but the most hazardous conditions of all were endured by the sailors manning the Arctic convoys. After the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Britain decided to help the hard-pressed Russians by dispatching war supplies—aircraft, Matilda infantry tanks, and trucks—that Britain could ill afford to spare. The first convoy, code-named Dervish, sailed for Archangel with seven freighters in August 1941, followed by a second convoy in September. By year’s end, eight British convoys had arrived in Russia without loss.

From August 1941 to the end of the war, 40 outward convoys were routed to the Arctic. The merchant sailors and their Royal Navy escorts faced pack ice, fog, and ferocious storms; perpetual night in winter and perpetual daylight in summer; and high latitudes that made even gyrocompasses unreliable, causing navigational errors—not to mention the menace of U-boats, land-based Luftwaffe raiders, and German capital ships sneaking out from Norwegian fjords. Ship superstructures, decks, and guns were constantly caked in ice, making the merchantmen and their escorts particularly vulnerable to mishap and attack.

Out of a total of 811 merchant ships that sailed from Britain to Russia, 33 returned to port with damage from weather or ice, 58 were sunk by the enemy, another five were lost in the Kola Inlet after arrival, and 720 reached port safely. The convoys carried four million tons of supplies, including 5,000 British and American tanks and more than 7,000 airplanes. Remarkably, only about 300,000 tons of supplies (7.5 percent) went down with sunken ships. Of 13 vessels that sailed independently from Iceland to Russia, five were sunk and three had to turn back. While the merchant losses on the Arctic convoys were comparatively light, the cost to the Royal Navy was high: two cruisers, six destroyers, two sloops, a frigate, two corvettes, four minesweepers, an armed whaler, and a Polish submarine.

Surviving a Submarine Attack

During the war, the Merchant Navy recorded many incredible sagas of survival by sailors after sinkings. One able seaman found himself drifting alone in the Atlantic, clinging to a substantial piece of wreckage, after his ship was sunk in the spring of 1943. All that he had was a raw cabbage and a snapshot of his wife. Occasionally munching a leaf of the cabbage, drinking rainwater and melted hail or snow, and talking to the photograph, he managed to survive for 18 days until a ship picked him up.

Even more remarkable was the story of Poon Lim, a young Chinese steward who took to a life raft when his ship, the Benlomond, was torpedoed on November 23, 1942, while sailing westward unescorted from Cape Town to Paramaribo, Dutch Guiana. He was the only survivor of a crew of 47. Subsisting on the small provisions he found on the raft, augmented by whatever fish and seagulls he could catch, Poon drifted for week after week. The combined effect of the equatorial sun, winds, and salt rotted his clothing to shreds and turned his skin into a mass of blisters, but he kept fighting to stay alive. He became so weak that he could not sit up, let alone catch fish with his makeshift line.

On the 133rd day, reduced to a scarcely breathing bundle of bones and in the last stages of starvation, Poon was spotted by Brazilian fishermen. They landed him at the port of Belem, where he was cared for at the Beneficiencia Portuguese Hospital. The Chinese sailor amazed his doctors and nurses by making a full recovery in just over two weeks. He was later decorated as a Member of the British Empire.

Ten months later, Poon Lim’s survival record was exceeded by two days. After discharging a cargo of ammunition in the Middle East early in September 1943 and bunkering at Aden, the freighter Fort Longueuil sailed for Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia. On September 19, she was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine south of the Chagos Archipelago. The ship sank in minutes, and only seven survivors managed to scramble aboard a life raft. The submarine surfaced alongside, but its captain said he could do nothing for the seamen. The raft carried only two days’ rations, and the men aboard died one by one.

By the 25th day, two Indian seamen named Mohamed Aftab and Thakur Miah remained alive. They rode the ocean currents for 3,400 miles, subsisting on raw fish and rainwater. On February 1, 1944, after 135 days aboard the raft, Aftab and Miah drifted ashore on the island of Sumatra. Natives found them and handed them over to the Japanese occupation forces, and the two seamen faced death. But the Japanese had second thoughts. They reasoned that the pair might be anti-British Indian spies and simply did not believe that they could have survived on a raft for so long.

So the two Indians were spared execution and held in a prison camp. Eighteen months later, at the end of the war, they were freed by troops of the British 14th Army, flown to Rangoon, and thence repatriated.

The Battle that Britain Could not Afford to Lose

For their staunch service as the very sinew of Britain’s survival and the Allied victory, officers and men of the Royal Merchant Navy were awarded five George Crosses, 213 Distinguished Service Crosses, 18 Distinguished Service Orders, 1,077 Orders of the British Empire, 1,717 British Empire Medals, 50 Commanders of the British Empire, and 10 knighthoods. They paid a high price—30,248 crewmen drowned or were killed in action. At the Merchant Navy War Memorial, a sunken garden walled with Portland stone close to the Tower of London, the names of 23,837 seamen who have no grave but the sea are emblazoned in bronze. The graves of another 8,000 of their shipmates lie in cemeteries scattered around the world.

In a strange turn of events, veterans of the Merchant Navy have never been invited to take part in the Remembrance Day (November 11) march-past at the Cenotaph in London’s Whitehall, during which the Queen and members of Parliament lay wreaths to honor Britain’s war dead. White-bereted veterans of Royal Navy escort ships in the Arctic convoys are present, but there is no one representing the ships they shepherded. At the poignant ceremony, which dates back to the end of World War I, the only recognition of the role played by the Merchant Navy in World War II is a wreath laid by a single representative who stands alongside the leaders of the armed forces.

Yet the Merchant Navy, along with British, Canadian, and American warships and aircraft, won the Battle of the Atlantic, possibly the most crucial campaign of the war. It was a battle that Britain could not afford to lose. Had it been lost, Britain’s capacity to wage war when it stood alone would have been irreparably damaged, the Allied buildup and invasion of continental Europe would not have been possible, and Hitler would have been free to concentrate all his resources against the Soviet Union.

Overlooked by the majority of historians, the sacrifice of Britain’s civilian fourth service in 1939-1945 has faded, sadly, from the national consciousness, although high tribute was paid to it when memories were clearer. During a speech in London in 1950, Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery, hero of the climactic Battle of El Alamein in October 1942, said, “Victory was won in Hitler’s war not only by the courage and skill of the fighting services, but also by the quality of the ships and men of the Merchant Navy who transported us to our overseas bases and battlefronts, and maintained us there till the job was done.”

Prime Minister Churchill wrote, “We never call on the officers and men of the Merchant Navy in vain,” and during his victory broadcast in May 1945 he declared, “My friends, when our minds turn to the Northwestern Approaches, we will not forget the devotion of our merchant seamen … so rarely mentioned in the headlines.”

On October 30, 1945, Parliament carried a resolution: “That the thanks of this house be accorded to the officers and men of the Merchant Navy for the steadfastness with which they have maintained our stocks of food and materials; for their services in transporting men and munitions to all the battles over all the seas, and for the gallantry with which, though a civilian service, they met and fought the constant attacks of the enemy.”

Well done. I love stories about the merchant fleets on both sides of the Atlantic. Esp. since they are stories seldom told.

Nice words but what did they give us? A wee button hole badge and no pay as soon as we took to the boats,

Rudyard Kipling would have written a fitting poem for the hardships that these men faced and the courage, devotion, and determination they displayed — day after day, year after year.