By Flint Whitlock

Thanks to the late historian Stephen Ambrose, his book Band of Brothers, and the HBO series of the same title, the legendary, extraordinary exploits of Easy Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), 101st Airborne Division, have become well known to a whole new generation.

And one of the most extraordinary men who served with that outfit is Lynn “Buck” Compton. His life story would make a great film or TV series in its own right. It has made for a great recently released book, Call of Duty: My Life Before, During, and After the Band of Brothers, written with Marcus Brotherton and including a foreword by John McCain.

From Lynn to Buck

To begin at the beginning, Compton was born in Los Angeles, California, on New Year’s Eve 1921. As might be expected, the young man hated his first name. “My mother’s father was from Lynn, Massachusetts,” he said, “and named Lyndley in honor of the town, so that’s where my name came from. But to me, Lynn was a girl’s name and always will be.”

He resolved to change it. Always a baseball fan, his favorite team was the L.A. Angels, a minor-league team in south Los Angeles. The team had a player named Truck Hannah, whose real name was James Harrison Hannah. Compton, at an early age, thought: “If he could have a nickname, why couldn’t I? One day in grammar school, I rolled around in my head the name—Truck Compton. Sounded tough, but I also sounded like a copycat. How about Buck? That was close enough for jazz. It was settled––Buck Compton was my new name. I informed all my friends that Buck was the only name I’d answer to. That was OK by them––nobody wanted a friend who had a sissy’s name.”

Growing up in Los Angeles, he also became a movie fan and a young extra in several films, even appearing in a few scenes with up-and-coming child actor Mickey Rooney. Unhappy with Compton’s efforts in the silent classic, Modern Times, star and director Charlie Chaplin fired him from the set. The Compton family lived a lower-middle-class existence during the Great Depression, and the loss of the meager movie extra income brought home by Buck was keenly felt. To take up part of the slack, he earned a few dollars a week as a caddy at a local golf course as well as a newspaper delivery boy.

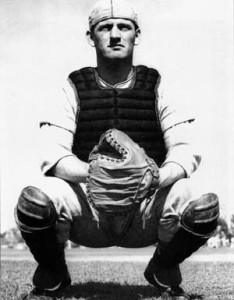

Besides being an avid baseball fan, Compton developed into a standout player. After he entered high school, he continued to pursue his interest in the game, becoming the all-league catcher his senior year. He also went out for the football team where the coach, a brusque, demanding man, never settled for less than 100 percent effort. It was a lesson Buck Compton never forgot. “Coach Bert’s voice helped push me through a lot of hard times, including the war years,” he said. “His presence became a part of me. Whatever mud or snow we were in, if our ammunition ran low or we didn’t eat for some time, Coach Bert was there. His voice ingrained its way into my head. I couldn’t shake that booming voice if I tried.”

ROTC at UCLA

In 1939, Compton graduated from high school and was offered a football scholarship to UCLA. But before he could enter college, tragedy struck; Buck’s father, plagued by feelings of inadequacy and alcoholism, committed suicide.

Crushed by the loss of his father and struggling to comfort his distraught mother, Compton said his high school football coach became a “tower of strength” for him and helped him get through that difficult time. He related, “Coach Bert became an example of what it means to be truly strong. Even when life throws you down, somehow you get up and continue; if you can help others in the process, you do that then, too.”

Compton then entered UCLA with his football scholarship but was required to work four hours a day on campus for 50 cents an hour. From 6 until 8 am each day, he picked up trash, then attended class, then spent his afternoons at football practice, then had another two hours in the evening picking up trash again. “Hoo boy,” he laughed, “I was really a big man on campus!”

During a meaningless game in his freshman year, while playing center, he was blindsided by an opponent with a block that nearly destroyed his knee. But he toughed it out and continued to play, albeit heavily taped up.

In his junior year, Compton went out for the UCLA baseball team and became the starting catcher (one of his teammates was Jackie Robinson). Compton was also named to the all-league team and later inducted into the UCLA Baseball Hall of Fame; he hoped that a major-league career was just around the corner.

While in school, Compton joined a fraternity. One of his fraternity brothers was Captain Dick Jensen, General George Patton’s personal aide who was later killed during the fighting in North Africa.

At UCLA, Compton was also enrolled in the ROTC program. “I didn’t know of anybody who was bothered by having to do two years of ROTC,” he said. “Our education was being subsidized by the American taxpayers, so none of us considered it unreasonable to give a couple of years’ military training in exchange for it. When I hear today of major state universities trying to bar armed forces recruiters on campus, that strikes me as unconscionable.”

Pearl Harbor

Although Buck Compton hoped to be playing major-league baseball when he graduated in 1943, life had other plans for him. On December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and other installations in the Pacific. Within days, the United States was at war with both Japan and Nazi Germany.

“After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor,” Compton said, “the climate in America changed almost overnight. There was a lot of concern that the Japanese would follow up Pearl Harbor by bombing the United States mainland. On campus, everybody’s outlook suddenly got very serious. We all knew active duty lay ahead. The only question was which branch of service a guy would go into.”

The war did not touch Compton immediately; he remained in school expecting to receive his draft notice any day. After playing against Georgia in the January 1943 Rose Bowl game (UCLA lost, 9-0), Compton received his induction notice; he was to report to the Officer Candidate School at Fort Benning, Georgia. As he waited at L.A.’s Union Station for the train that would take him and several hundred other recruits eastward, Compton mused that everyone seemed to be feeling a sense of duty. “We had been waiting for our call, and this was it. It was our responsibility to go and fight,” he said. “Young men heading off to war have no idea of the darkness that lies ahead. We certainly didn’t, anyway. The atmosphere on the train bordered on a party.”

The festive atmosphere vanished once the recruits reached Columbus, Georgia, on the outskirts of Fort Benning. Buck Compton was anxious to get into uniform, begin OCS, and prove that he had what it took to be an officer and a leader of men.

It would take a while. “Our status in Officers Candidate School felt strange,” he said. “We were neither fish nor fowl. We weren’t sworn in yet as soldiers, but we were officially on active duty with a unit. We didn’t have rank yet, and we dressed like privates. It would take the full 90 days at Benning until we received our commissions.” Finally, Compton and the others in his class received the gold bars of second lieutenants and eagerly anticipated their upcoming assignments.

Ballplayers in the Army

As it turned out, Compton received orders directing him to report to the 176th Infantry Regiment, a component of the Virginia National Guard at Benning, where his duty each day was teaching a one-hour class in aircraft identification. The rest of his day was spent sleeping late, eating, relaxing, eating, going for a swim at the officers’ club, eating, and just plain goofing off. If this was the Army during wartime, he was mightily bored by it.

Then one day Compton was assigned to play baseball for the regimental team. As the majority of major-league ballplayers were in the service, the regimental teams were quite good. “Nearly all baseball players were prevented from seeing combat,” observed Compton. “The great Joe DiMaggio, as well as Hank Greenberg, the Tigers’ star power hitter, were among the many ballplayers who asked for combat duty but had it denied.”

Also at Benning was Bob Waterfield, who had been the star quarterback at UCLA when Compton was there. Waterfield was in the process of organizing an on-post football team and wanted Compton to be his assistant coach. At the time, Waterfield was married to the sexy movie starlet Jane Russell, and they lived in on-post housing. When out in the field on maneuvers, Waterfield even requested that Compton escort his wife to dances and parties.

Compton recalled that one day, when he was visiting the Waterfield quarters, “Bob seemed totally engrossed in the playbook he was mapping out, and I remember thinking that if I were married to Jane Russell, I’d never give football a second glance.”

Compton continued to play baseball for the regimental team but was growing more discontented by the day. Although many soldiers would have given their eyeteeth for the privilege of playing baseball for the duration in a safe, cushy, stateside setting, he felt that there was a job to be done and a war to be won––and it would not be won on the baseball diamond.

The Airborne: Escaping the Baseball Diamond

Knowing that the regimental commander would likely quash his application to transfer to another outfit, Compton learned that transfers were being automatically approved for anyone wanting to become a pilot or join the paratroops. He noted, “Flight training took a full year to make it up the ranks from cadet to pilot. I thought the war would be over in a year––we all did. But jump training only took a month.” Compton put in for jump school.

“Overseas was where the action was. I wanted to be in the action. I wanted to win,” said the ever-competitive Compton, who looked forward to learning how to leap out of airplanes.

The parachute school was right there at Fort Benning, where Compton and several hundred others, officers and enlisted men alike, were put through the rigorous, physically and mentally demanding challenge of airborne training.

For four weeks Compton gutted it out, determined to earn the coveted, silver-winged badge of a paratrooper. At last the course was completed and Compton received his wings. He was then assigned to the 515th PIR, which would soon become a part of the newly formed 17th Airborne Division at Camp Mackall, North Carolina.

Shortly after joining the 17th Airborne, Compton received new orders directing him to report to the 101st Airborne Division, which was already in training in England. One of Compton’s former football teammates at UCLA had seen his name on a list of airborne officers, pulled a few strings, and had him sent to the 101st.

A “90-Day Wonder”

In December 1943, Compton and several thousand soldiers crossed the Atlantic on the former luxury liner Queen Elizabeth, which had been converted into a troopship. Once the ship docked in Scotland, Compton took a train southward to the small, picturesque English village of Aldbourne, where he found E Company, 506th PIR, commanded by 1st Lt. Thomas Meehan, encamped. They had been there since August 1942.

The officers of E Company were quartered in a large, two-story manor house located on Aldbourne’s town square, while the enlisted men were housed in stables adjacent to the manor house and also in Quonset huts. It was cold, wet, and clammy. Heat and hot water were in short supply, but there were gripes aplenty.

Compton was taken to meet the 1st Platoon commander, 1st Lt. Dick Winters, and his assistant, Lieutenant Harry Welsh. Winters impressed Compton greatly. “He was from eastern Pennsylvania,” Compton recalled, “and had grown up with a strict Mennonite background. He was a hard worker, serious, and had paid his own way through college.” He had also earned his commission through OCS and had been one of the original members of Easy Company, surviving all the hell that Captain Herbert Sobol, the company commander at Camp Toccoa, Georgia, could dish out.

Compton’s first job was as assistant platoon leader of the 2nd Platoon. He said, “This was it. This was why I quit playing baseball and volunteered to be a paratrooper.” He also noted that his life would never be the same. The company was made up of about 150 soldiers, and the 506th PIR had nine companies, or almost 1,500 men. In total, with all of its organic units, the 101st Airborne Division had about 10,000 soldiers.

Second Lieutenant Buck Compton also discovered that it was difficult for a newcomer, especially a “90-day wonder,” to be welcomed into the ranks of a proud, closely knit, and well-trained group of soldiers. As only one-ninth of the regiment, E Company, noted Compton, “still comprised a stalwart and elite group of men. I doubt if anyone would ever describe E Company as ‘average.’ Throughout the course of the war, the unit encountered situations that required extraordinary bravery, as many units did. I am honored to be included in their ranks. But when I joined the unit in December 1943, it took me a while to feel like I belonged.”

Fitting into Easy Company

Like many second lieutenants, Compton quickly learned that it was the sergeants who did much of the “leading” in a platoon and company, and he was blessed with having some exceptionally fine sergeants, men such as Don Malarkey, Bill Guarnere, and Joe Toye.

Compton said that he would tell one of his NCOs what needed to be done, and the sergeant would make sure it got done. “I just sort of stood around and watched them perform. I never found any occasion to administer any kind of discipline or chew anybody out, the way some officers do.”

He also ingratiated himself with his men by refusing to build barriers between himself as an officer and them as enlisted men; he enjoyed shooting the bull and playing poker with them. Lieutenant Winters disapproved of such fraternization, and he and Compton once got into a heated argument about such un-officerly behavior.

In the end, Compton realized the reason for such rules. An officer might be reluctant to order an enlisted “buddy” into carrying out a deadly mission but, as he said, “I’ve never found it easy to order anybody around. I’d rather ask someone for something than demand it. It was not in my nature to be anything other than myself. If I consider somebody a friend, enlisted man or otherwise, I don’t hide it.”

Compton’s easygoing attitude is probably one reason why so many of his men grew to have such affection for him. One of his men, Edward “Babe” Heffron, said later, “Buck is not only one of the nicest men I’ve ever known, a very humble man, but out of all the officers in Easy Company, Buck was closest to the guys.”

The “Big Step-Off”

During the first half of 1944, training for the invasion of the European continent continued at an ever-quickening pace. Several practice jumps a week were scheduled, and the airborne troops rarely went anywhere at a walk. It was always double time. When they weren’t jumping out of airplanes, the paratroops were on the rifle or grenade range, or the bayonet course, or improving their hand-to-hand fighting skills.

While training in England, Buck Compton broke an ankle, but it healed quickly and within a few weeks he was back taking part in maneuvers with the rest of his platoon. He knew something big was in the works; throughout the spring of 1944 huge swarms of B-17 and B-24 heavy bombers, on their way to bomb enemy targets, covered the sky above Aldbourne, and scuttlebutt was rife with speculation about the impending invasion of France. Compton could not wait for it to begin.

In May 1944, the division was alerted that the “big step-off” was imminent, and E Company was moved from Aldbourne to an encampment at Upottery Airfield near Devon on the southern coast.

“Tension grew in anticipation of what we knew would soon come,” he recalled. “We went through days of extensive briefings, and were shown maps and sand tables and told to memorize everything we saw.”

Their specific mission soon became clear. While over 150,000 seaborne troops were scheduled to hit five invasion beaches along the Normandy coast, three airborne divisions, two American and one British, would precede the beach landings and be dropped behind enemy lines to sow confusion, attack enemy positions from the rear, and seal off routes the Germans would likely use to smash into the flanks of the invasion sites.

The 101st Airborne’s mission was to drop in the vicinity of Ste.-Marie-du-Mont, seize four causeways behind Utah Beach at the base of the Cotentin Peninsula, and prevent any German incursions into the invasion area where the 4th Infantry Division would be wading ashore.

The paratroops knew that if they failed, the 4th could be driven back into the sea. They also knew that if the 4th failed to secure the beachhead, there would be no rescue for the airborne divisions. So both the airborne and seaborne troops were vitally dependent upon each other’s success. Delayed for a day by a major storm ravaging the English Channel, Operation Overlord got under way late on the night of June 5, 1944.

As troopships, support ships, and warships left their ports along the southern coast of England, the heavily laden airborne forces (each man carried between 70 and 100 pounds of equipment) were gathering at their airfields, climbing into hundreds of aircraft of the United States Army Air Forces Troop Carrier Command that would deliver them to hostile shores (it took two C-47s to carry one 40-man platoon), and taking off into the dark night.

Landing Without Equipment

The flight across the Channel was routine; the skies belonged to the Allies. About three-quarters of the way to France, Compton noted, “Our crew chief came back and took the door off the airplane, leaving a hole in the side.”

As the first man in his “stick” of paratroopers, Compton shuffled to the doorway and looked out. The black sky all around was filled with transport planes in formation. Down below, the French coastline came into view. Then, as they crossed the beaches, “tracer bullets and antiaircraft started to appear,” he said, “red, blue, and green tracers, spectacular and deadly against the night sky.

“As we neared our drop zone, the weather grew overcast, and more and more antiaircraft flak began to hit near our plane. Nothing ever hit our plane directly that I was aware of. Some flak I could see exploding outside the door in the fog bank. Mostly it was just a crackling sound. I had never met our pilot, so I knew nothing about him. I assumed he was on course and would slow down enough to let us jump. What else could I assume?”

The red light near the door went on, signaling the men that it was time to stand up, hook their static lines to the steel cable that ran the length of the interior of the fuselage, and prepare to jump. Stomachs tightened as the antiaircraft fire became more intense. In other planes, Compton learned later, panic ensued as bullets and shells and shrapnel ripped through the thin aluminum skin and the unprotected bodies of paratroopers. Some troops bailed out over the water while others, their planes on fire, rode their craft down to a fiery end.

Suddenly, sooner than Compton expected, the red light went off and the green “jump” light came on. Operating on instinct born of endless training, Compton and his men moved quickly and threw themselves out into the black, blazing night. He hoped that they were somewhere over their drop zone.

The C-47’s pilot had not, as Compton had assumed, throttled down. The plane was still rushing along at top speed. The shock of the prop blast was more than Compton expected; it broke the plastic chin cup off his helmet and ripped the leg bag containing his carbine, mortar rounds, and extra equipment off his leg.

As he descended, Compton could hear the sounds of gunfire below but none came close to him. “I drifted into an orchard––some sort of enclosed field with hedges all around it. My landing was good, a two-footer. Everything was eerily quiet. A few cows mooed in the distance. I was completely alone.” Compton did not find out until later that his company commander, Lieutenant Meehan, was killed when his transport plane was shot down.

While lying in the darkened field, Compton reflected that, except for his trench knife, a canteen, and a couple of grenades, he was completely without equipment of any kind. “Neither my first jump at Benning nor my first jump into enemy territory had gone anything according to plan. Nothing had been on schedule. Nothing had been smooth. What could possibly come next?”

He would soon find out.

Making Order from Chaos

The 101st Airborne Division’s first combat jump had been part success, part disaster. Like its sister airborne division, the 82nd, units were scattered far from their intended drop zones. Vital equipment was missing. Officers and NCOs were lost, injured, or dead. Thousands of men had no idea where they were, or where the other men in their platoons were.

As Compton learned later, “Some paratroopers were shot on the way down, and some fell into land that had been flooded by the Germans and drowned. Some fell on trees, buildings, or antiglider poles.”

The confusion did serve one good purpose. The Germans had little idea of the true scope and nature of what was happening. In addition to the widely dispersed paratroop landings, dummy parachutists had also been dropped by the Allies, giving the impression of a much larger airborne invasion than had actually taken place. German commanders did not know whether to send their troops in one direction or another, or to just sit tight and wait for further orders.

While trying to get his bearings in the dark, Compton could hear gunfire off in the distance, could see tracers still criss-crossing the night sky, could hear the steady drone of aircraft engines delivering more paratroopers, could see the dim forms of men floating down from the sky.

“Theoretically,” he said, “I should have been running into guys from my own platoon, but I wasn’t even running into guys from my own division!”

Suddenly another airborne soldier landed about 20 yards away from him in the orchard; he was from the 82nd. The two of them headed out in the direction they were supposed to go: toward the beach. As they walked, other stragglers from other outfits began joining them. They came across a lieutenant from D Company, 506th PIR, who had broken his leg upon landing. Seeing Compton without a weapon, he gave him his Thompson submachine gun and waited to be found by either American medics or German troops.

Compton’s First Kill

The ad hoc squad continued on. At times other American troops were added, and German troops, too, gave themselves up to the marching paratroopers. As the sky gradually lightened, the sounds of the battle coming from Utah Beach began to punch the air.

Compton remembered, “One shell from a ship flew in like a freight train and landed about 50 feet away from us. It thudded, shaking the ground, and stuck fast––a dud. If it had exploded, it would have killed us for sure.”

Compton’s group marched on, listening to the sound of the naval guns and outgoing German artillery becoming louder and more intense. Up ahead, taking cover beside a building, he saw Lieutenant Winters; Sergeants Malarkey, Guarnere, and Toye; and a handful of other enlisted men. Altogether the ensemble numbered about a dozen men. Compton breathed a sign of relief.

Pulling out a map, Winters told Compton that they were at an estate known as Brecourt Manor, about three miles west of Utah Beach. Suddenly, a battery of German 105mm guns began firing nearby, their rounds heading toward Utah Beach. Winters directed Compton to recon the area; Compton moved toward the sound of the guns while the GIs kept the Germans’ heads down with machine-gun fire. He soon discovered the battery of four guns, connected by trenches, firing on the causeways the 4th Infantry Division was using to march inland.

Compton jumped into one of the trenches, aimed his borrowed Thompson at two surprised, well-armed enemy soldiers, and pulled the trigger. Nothing happened. The firing pin was broken. The Germans prepared to fire.

At that moment, Sergeant Bill Guarnere, who without Compton knowing it had followed the lieutenant across the field and into the trench, blasted one of the enemy soldiers with his rifle. The other soldier scrambled out of the trench and began running away, but Compton lobbed a grenade at him.

“It detonated in the air right above the German’s head, killing him instantly,” he said. “That was my first kill. Ask me today what it’s like to kill a man in combat and I don’t say much. I have no idea who he was, what he did outside the war, or if he had a wife or family. You just don’t think. A man is trying to kill you, and you either kill him first or be killed waiting to assess the situation. I doubt if the choice I made to throw the grenade was even conscious. A sense of duty had long since taken over. We knew what our orders were, and we followed through as best we knew how.”

The battle for Brecourt Manor went on for hours, with both sides trading machine-gun fire. Compton said, “I don’t remember when victory was at last declared at Brecourt. All the German guns were eventually destroyed, and Winters must have ordered a fallback to our original starting point. History has shown that troops landing at Utah Beach had an easier landing due in part to what was accomplished at Brecourt. I’m happy about that. If our actions saved any of our boys’ lives, that’s part of what we were there to do.”

For his deeds at Brecourt Manor, Compton was awarded the Silver Star. It was only later that he discovered that the dozen Americans had taken on 60 Germans.

The Battle of Carentan

The days following D-Day were something of a blur for Buck Compton. He recalled surviving nearby grenade and mortar explosions without a scratch, but the exhaustion of combat has dimmed his memory of that period.

One painful incident stuck in his mind, however. He and a private were patrolling along a hedgerow and spotted two other soldiers skulking along another hedgerow about 50 yards away. Compton noticed that both were wearing German camouflage ponchos of the type usually worn by SS troops, and one was carrying a Mauser rifle.

Compton and the private opened fire, killing both men. It was only when they went to examine the bodies that they discovered the dead men were both Americans; why they were wearing German ponchos and carrying a German rifle Compton never knew, but the incident still disturbs him greatly.

“Out of all the horror of war,” he said, “the guilt of survival is one of the things that haunts me most to this day. I will never know why I survived when so many others did not. When it comes to understanding any of this, I have long since given up trying.”

One of the key cities in Normandy is Carentan, between Utah and Omaha Beaches. Whoever controlled Carentan controlled an important road network through Normandy. Both sides knew this, and the Germans were just as intent upon holding Carentan as the Americans were in taking it away from them. The tough German 6th PIR was securely entrenched in part of the city’s outskirts––the part that American troops were ordered to seize.

The battle for Carentan began with an American artillery bombardment that lasted several days. Then U.S. P-38 fighters worked over the town from the air. With Lieutenant Winters now in command of the cobbled-together E Company, the entire 2nd Battalion was ordered to make a night approach to Carentan, then was ordered to turn around and return to its positions.

The paratroopers, back in their foxholes, then began taking enemy artillery fire. After the shelling subsided, the battalion was ordered once more to advance into the city. Compton described the place as being “like a ghost town. It was a shambles––crumbled buildings, dead Germans lying all over. We walked down the main street and out the other side. I’d estimate we saw a dead body every 10 feet or less. Most of the bodies had been pretty well mutilated by our artillery. I didn’t see any townspeople; they may have been hunkered down in their basements.”

As they left the shattered city and reentered the rural area beyond, the paratroopers were sprayed with machine-gun fire. A pitched battle lasted a while, then some Sherman tanks arrived and silenced the enemy. E Company moved back into Carentan, where it stayed for a few days, awaiting new orders. But combat was finished for them. After a month in France, the 101st, along with the 82nd, was ordered to return to England to prepare for whatever new mission might emerge.

Preparing for a New Airborne Mission

While other Allied units crossed the English Channel to take part in Operation Cobra, the breakout from Normandy, and the dash toward Paris, the airborne divisions enjoyed a more-or-less “normal” military life of training, training, and more training.

Interspersed with the training periods, though, was plenty of relaxation and leave time. The soldiers explored London and other sites on their days off, even being invited to dinner at the homes of Aldbourne residents who, in spite of rationing and wartime shortages, were more than generous to the young Yanks far from home.

Several times during that summer the division was alerted for combat jumps, but the missions were cancelled; the Allies were making such swift progress across France that the land armies had secured the intended drop zones before the airborne troops could be dropped on them.

It was not until September 1944 that the airborne troops, still encamped in England, received another assignment. This one was code-named Operation Market Garden and had been devised as a way of avoiding the fortifications along the Siegfried Line. The plan called for airborne troops to land behind the defenses, secure bridges over the Rhine River in German-occupied Holland, and make a lightning thrust into the Ruhr, the industrial heart of Germany. There was even hope and speculation that, if successful, Market Garden could end the war in Europe before Christmas.

For this bold operation, the normally cautious British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery detailed three British and Canadian airborne divisions to take the bridge at Arnhem. Simultaneously, the American 82nd Division would grab the bridge at Nijmegen while the 101st would assault and hold the crossing over the Wilhelmina Canal at Eindhoven.

Operation Market-Garden: A Costly Failure

Just as almost everything went wrong during the first hours of Operation Overlord but turned out right, almost everything went right during the first phase of Operation Market Garden but then went horribly wrong.

The initial parachute landings were flawless. There was little enemy fire, and Dutch civilians cheered the arrival of the Allies in their towns. But then the whole plan started to unravel. There were more German units in the vicinity than intelligence had accounted for. Some airborne units dropped into the midst of enemy formations and were cut to pieces. Radios did not work. The armored columns that were supposed to arrive to reinforce the lightly armed paratroops were late and were decimated. Airborne units were surrounded and cut to pieces.

In a fierce battle in a farmyard at the village of Hegel during the German counterattack, Compton was hit in the buttocks by a bullet. He was evacuated to an aid station in Eindhoven on the hood of a jeep.

Compton realized the mission was a costly failure: “When E Company jumped on that sunny day in September, we had 154 men. By the time Easy Company left for France in November, 88 days later, a third of the company was either dead or wounded.”

After receiving initial medical treatment, Compton was sent back to a civilian hospital in Oxford, England, to recuperate. A little more than a month later he was back with E Company, now billeted in Reims, France. As he slowly regained his strength, the 101st continued to train for whatever new mission might come its way.

The Battle of the Bulge: Blunting the German Counterattack

A hard winter hit northern Europe, the worst, some said, in more than a century. The Allied operation ground to a halt along the German border with Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France. Everyone thought that they would just remain in place for the winter, try to stay warm, and then resume the offensive when spring came. It did not quite work out that way.

Adolf Hitler, with both his eastern and western fronts being squeezed by Germany’s enemies, decided to gamble on one last throw of the dice. He launched Operation Wacht-am-Rhein, the biggest German offensive since Barbarossa, the June 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union, in the middle of December 1944.

Hitler’s goal was the capture of the Allies’ chief supply port at Antwerp, Belgium, and to reach the city his troops would need to take the vital crossroads town of Bastogne, Belgium. The offensive would be known by the Allies as the Battle of the Bulge.

At first, the Germans’ surprise assault succeeded brilliantly. Caught totally unaware, American forces were forced to give ground. Thousands of U.S. troops, many completely raw and without prior combat experience, were killed or captured, or they fled for their lives across snowy fields.

With their lines shattered, the Americans needed to bring in divisions from other sectors to plug the gaps; the 101st Airborne was one of those called upon. The division boarded trucks at Reims and spent more than a day trying to reach the front near Bastogne. All along the highway leading into Bastogne, Compton and his men encountered long lines of panicked, demoralized American troops retreating from the enemy.

Without winter clothing and low on ammunition, the 101st was thrown into the breach. The paratroopers marched to the east of Bastogne and were told to dig foxholes in the frozen earth. A dark, damp fog settled over their positions. The temperature plunged to below zero.

Soon it began to snow. The sounds of German tanks could be heard. Sporadic small arms and artillery fire hit around paratroopers’ foxholes, but the anticipated big attack failed to materialize. The tension, though, continued day and night. Thanks to the cold and the noise and the German flares that lit up the dark sky, sleep was hard to come by.

Just before Christmas, the Americans got the word that Bastogne was surrounded by the Germans. Compton and his men went without shaving, without washing. He and many of his men came down with frostbite. Compton recalled, “We were alone, out in the woods, surrounded, desperately low on supplies. We were in day-to-day survival mode. Build the occasional fire. Melt some snow. Find something to eat. Cook it in your helmet. Stay out of harm’s way. Just do what you need to do to get through the day.”

The Germans sent a demand to Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, the 101st Airborne Division Artillery’s commander, that he surrender his forces in and around Bastogne. McAuliffe’s one-word reply has become emblematic of American fighting spirit: “NUTS!”

Then, two days before Christmas, the thick overcast that had kept Allied planes grounded finally lifted and the sun came out. American pilots hammered German formations from the air.

On Medical Leave

Yet the battle for Bastogne was not over. In fact, for Compton and his men, it had barely begun. In early January, a heavy German barrage shattered the trees in E Company’s position and threw branches and red-hot shrapnel around in deadly fashion.

Compton said, “Very suddenly, broad daylight, really bad shelling started coming in––big, heavy stuff. Landing on us was the most shocking display of firepower I had ever seen. It was absolutely merciless. Shrapnel flew and shredded every which way. Bursts of dirt and snow exploded all over. You could feel the ground bounce. You could taste gunpowder in your mouth. For some time, all was complete chaos. Then the shelling stopped almost as suddenly as it began.”

Compton’s platoon area was a complete shambles of shattered trees, downed limbs, smoldering ground, blood, and bodies. “It’s a terrible thing to see your guys like that,” he said. “Death was everywhere.”

Two of his NCOs, Guarnere and Toye, were badly wounded. Realizing that his portion of the front line would be unable to hold if the Germans launched a ground attack, Compton took off in a rage for the company command post in an effort to get medics and reinforcements to his position.

By this time, Winters had been promoted and reassigned to battalion headquarters. Taking his place as commander of Easy Company was a haughty lieutenant named Norman Dike; he and Compton had never got along, and Compton was furious that Dike was not at the company command post. Storming back to his platoon’s position, Compton could not contain his emotions any longer and broke down sobbing at the loss of so many of his men––many of whom he had been with since Normandy. When it had gone into the line around Bastogne, Easy Company had had 120 men; now, only half that number remained alive and capable of fighting.

A short time later, perhaps thinking that Compton was reacting to the strain of battle, the 506th PIR’s commander, Colonel Robert Sink, pulled him off the line and out of combat.

With frostbitten feet, Compton was evacuated to a hospital in a rear area, but he would not stay there. Somehow he managed to get back to his platoon; he wanted at least to say goodbye to his men. It was a short, bittersweet parting.

“Survival Seemed so Implausible”

By the time Buck Compton recuperated from his frostbite, the 101st Airborne was in Austria and the war was nearly over. A friend helped him get the job of running the Army’s athletic programs for the GIs in Paris.

It was a cushy job, and there is no doubt that Compton’s time in combat earned it for him. Yet, he was troubled that he had survived and so many others had not. “Survival seemed so implausible,” he said, reflecting upon that time, “but some had made it to the end. I was one of the lucky ones.”

In December 1945, Buck Compton came home from Europe. Discharged from the service, he returned to civilian life in California. But his military career had made a deep and lasting impression on him, and he joined the active reserves, retiring 20 years later as a lieutenant colonel. He reenrolled at UCLA to finish his college education, bought a used car with the money he had saved during the war, and even went out for the baseball team again. He looked up his old girlfriend, Jerry Star, and they married in May 1946.

Believing he had what it took to be a professional baseball player, he tried out for and made the AAA Pacific Coast League Spokane Indians. But his wife was not happy with his career choice. She pointed out that she wanted to live in Los Angeles, not Spokane, and the job paid only $300 a month. Reluctantly, he turned down the contract and looked around for something else to do. With school out for the summer in 1946, Compton landed a job with one of the movie studios as a laborer, but it was a dead-end job burdened by what he felt were senseless union rules.

One day a friend suggested that he apply to law school; a career in law was the furthest thing from his mind, but he decided to give it a go. Strings were pulled, and Compton soon found himself enrolled in Loyola University’s school of law; the G.I. Bill paid for his tuition and some of his expenses.

But, as one door opened, another closed; Compton’s wife left him, a not infrequent occurrence among returning veterans.

Compton Joins the Police Force

One day while in Los Angeles, Compton ran into an old acquaintance, Jack Colbern, a man who had umpired several of his baseball games at UCLA. He suggested that Compton apply for the police force, where his athletic talents could be put to use on the department’s semi-pro baseball team.

Intrigued by the idea, Compton applied, was accepted, and soon found himself on the force. For three months, while he underwent training, he also took night courses at Loyola law school and studied on weekends. In what little spare time he had, he played ball for the police team. He was also active in the Army reserves, spending one weekend a month and two weeks each summer drilling with an armored unit. It was a brutal schedule, but Compton loved it.

As soon as he graduated from the police academy, Compton was assigned to plain-clothes duty, an unheard-of first assignment in any police department today. He also switched his reserve military duty from armor to the Office of Special Investigations (OSI), a unit that had both criminal and counterintelligence functions, and was assigned to Maywood Air Force Base in Los Angeles County.

He noted, “I loved my job with the police department. I’ve always been very fortunate–– not everybody gets to work at what they like to do.”

Although he really had no time for dating, one day his uncle who worked at a movie studio fixed Compton up with a young lady who worked as a secretary there. Her name was Donna. The two of them hit it off perfectly from the first date, and they were married in October 1947. They had two daughters, Syndee and Tracy, and their marriage would last a lifetime.

Despite his very full schedule, Compton noted, “Donna hung in there and never complained once about the life we were leading. She always had a smile. If I lived another 80 lifetimes, I could never say enough good things about her.”

“Some of the Grimmest Work I Would Ever Encounter”

In June 1949 Compton graduated from law school and passed the bar exam, but he stayed on with the police department. He was transferred to the Detective Bureau, an assignment he called “some of the grimmest work I would ever encounter.”

After less than a year with the bureau, he was transferred to the Central Burglary Division, an assignment he thoroughly enjoyed for the next two years. With his law degree in hand, and through the connections he was making doing police work, Compton left the force in 1951 and was hired as a deputy district attorney for Los Angeles County, the first ex-police officer in L.A. to make such a switch. In this capacity, over the next two decades he found himself involved in a number of high-profile cases, but none more so than the trial of Sirhan Sirhan, the man who shot presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy in June 1968 at L.A.’s Ambassador Hotel.

Compton said, “The senator lived until the early morning hours of June 6, 1968. Ironic for me—June 6 would always be D-Day in my mind. Twenty-four years earlier, June 6, 1944, I had parachuted into Normandy.”

He also noted, “Because the crime happened in their jurisdiction, the LAPD was the primary investigative bureau responsible for the case.” Compton was put in charge of the investigative task force.

The massive investigation went on for months, and an insurmountable mountain of assembled evidence built up. Theories that the gunman was part of a larger conspiracy were shattered by the careful investigation by Compton’s team. On January 7, 1969, seven months after the assassination, the case went to trial. Fifteen weeks later, the case was handed to the jury, which came back with a guilty verdict; Sirhan Sirhan was sentenced to death in the gas chamber.

“We had won,” said Compton, “but I felt anything but triumphant. Justice was done. Sirhan Sirhan killed Senator Kennedy. Under laws established by a civilized society, a killer received the justice he deserved.” In 1972, however, California abolished the death penalty and Sirhan’s sentence was changed to life imprisonment.

Late Career and Retirement

In 1970, California Governor Ronald Reagan appointed Buck Compton to the position of Associate Justice of the California Courts of Appeal.

“I was ecstatic,” he said. “I never dreamed I would be offered such a position. It was very rare for someone who hadn’t served at a lower level such as Superior Court to go directly to the Courts of Appeal.” As far as he knows, he is the only ex-police officer ever to sit on the Appellate Court in California, if not the whole country. He remained on the bench hearing appeals and writing opinions until he stepped down in 1990 at age 68. He and Donna then moved to the San Juan Islands off the coast of Washington State and built a home to which they retired; their two daughters lived nearby. Sadly, in 1994 Donna developed serious medical problems and passed away suddenly. Compton was devastated.

“I only cry at three things: the death of my father, the love I have for America, and the memory of Donna,” he said. The island house became too lonely for him and so he moved in with his daughter Tracy and her family in their home on the mainland. Life, however, still held new opportunities for Compton.

Retelling the Past

In the early 1990s, he was interviewed by historian Stephen Ambrose for a book he was writing about E Company, 506th PIR; it was entitled Band of Brothers. The book became a best seller.

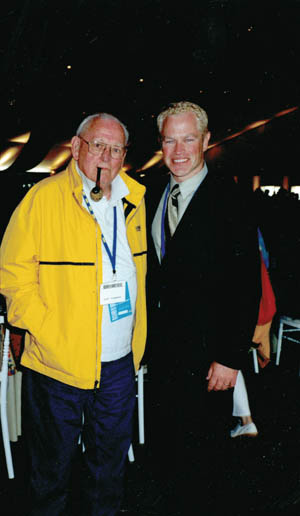

Then, after the stunning success of Steven Spielberg’s 1998 World War II epic Saving Private Ryan, which did much to rekindle public interest in World War II, plans were made to turn Band of Brothers into a 10-part miniseries for HBO. Along with several other E Company veterans, Compton became an unofficial technical adviser for the series, often conversing with and giving tips to actor Neal McDonough, who played him in the film.

Although he was not totally pleased with the artistic license that was taken for dramatic purposes, Compton realized that certain scenes had to be invented or reality altered for the sake of viewer impact. He was pleased, however, with all the attention and recognition that the book and series focused on the members of his old unit.

“The only downside,” he said, “is that not everybody who deserved recognition got it. The starting point of Easy Company was about 150 guys, maybe 200, while we were in combat in Europe. A lot of them did some pretty brave things and suffered a lot of hardship. Many were wounded and killed. All kinds of guys did as much as or more than I did, whose names were never heard of or mentioned.

“That’s not anybody’s fault. It would be simply impossible, if you were in Ambrose’s spot, to write a book that mentioned everybody. The book and the series had to be limited in scope. But I can understand that there are guys who feel left out. Like, ‘Why is Compton mentioned and not me?’ I don’t know the answer to that. But I hope people will take it that we were representatives of combat soldiers everywhere.”

In thinking of other “combat soldiers everywhere,” Compton acknowledged that there is a certain amount of “glamour” that attaches to paratroopers “due to the fact that we jumped out of airplanes. But we didn’t have it as hard, for instance, as the guys in the 1st or 4th or 29th Divisions, who were grinding it out day after day in Europe, many of whom were not pulled back from the line to England after 30 days like we were. Or beyond that, the poor guys who served in the Pacific. I wouldn’t have traded with the guys in the Pacific for anything. None of them got the recognition we did.”

Living today in Anacortes, Washington, Compton is a volunteer for the Skagit County Republican Party headquarters, gives a variety of lectures, and even has a radio commentary program.

Compton also remains fiercely proud of his military service, yet sincerely humble. When thanked for his service, he replies, “I spent three years on active duty, saw some combat in Europe, and suffered a minor wound. I got back in one piece and had the luxury of having a great family life and a rewarding career. I consider three years and a wound a small price to pay for the privilege of being born in America. The people to whom we all must pay our respects and honor for their service are those who gave life and limb in performing their duty.”

As he closes the story of his life, Buck Compton leaves the reader of his new book with one final thought: America is still the land of unlimited opportunity. “You can have anything or be anything you want in this country if you put your mind to it,” he says. “Don’t let anybody take that away from you.”

I can’t read enough about our soldiers who took it to the Nazi bastards that had bullied their way all across Europe! Those guys (and gals) in uniform and resistance fighters are and rightfully should be, regarded as our most precious National Treasure!! We must NEVER forget their bravery and sacrifice for all they did to put an end to the unimaginable suffering and twisted whims of Hitler and the like. They stared pure evil in the face and put them down like the rabid animals they were! Nothing but eternal respect and gratitude from this USAF vet and proud AMERICAN PATRIOT!

MAY GOD BLESS THEM AND OUR GREAT COUNTRY!

Every single year our entire family after Christmas meal binge watches the entire Band of Brothers series. Now there are additional sources that are great additions. It’s just a small way to honor these greatest of our American service people that ever lived.

Living in Oregon, a few years ago I had the greatest honor of meeting & visiting with TSGT Don Malarkey who was born & raised in Astoria, Oregon. He spoke unendingly of his strong feelings of Brotherhood with & among members of the 506 PIR. He has passed on now. But our short visit in his home remains one of my life’s most impactful times. Very special gratitude goes to each & every Member of the 506th.

Years ago a fellow WW2 reenaactor told me that Dick Winters was going to get a public talk. I drove from Pittsburgh to his home and we headed east, complete in airborne uniforms, where we met others of his unit. Mr. Winters spoke at a small high school in a town east of Harrisburg, talking about leadership. Every so often he’d stop, and part of the miniseries would play on the big screen behind him on the stage. It was a wonderful chance to listen to a true hero from the U.S.A. I’ll always be thankful to my friend for letting me know about the talk (the auditorium was packed) and a chance to actually see and hear Mr. Winters, one who truly knew about how to lead.

I was only 12 when the war was over. It was a great part of my life. One of my brothers was in the Pacfic and one in Europe. They both got home safe. Frank was a paratroper with the 17th airborne. He was in the gliders but, when they cracked up on landing in France he enlisted in the paratropers as it was safer. Every day I think of the boys in my home town that never made it home. Every one wanted to enlist. One man in my town had a natural limp. When he was check out he was turn down. He was told we need fighting men, you have a limp. That was the worst thing that you could tell him.He said to the Army doctor. “Come out side I show you if I can fight” Then he oftered any one out. They passed him just to keep him quiet. I have a picture of him in combat dress in Paris on his way back up. This was the men of the 1940’s

Long way to tipperay

Br .. …. …. ….