By John Domagalski

Admiral Ernest King could not believe what he was reading. The graying 63-year-old chief of U.S. naval operations had been awoken from his sleep. An overdue message from the Guadalcanal battle zone had finally arrived at his headquarters during the early morning hours of August 12, 1942. It was three days after the sinking of the USS Astoria.

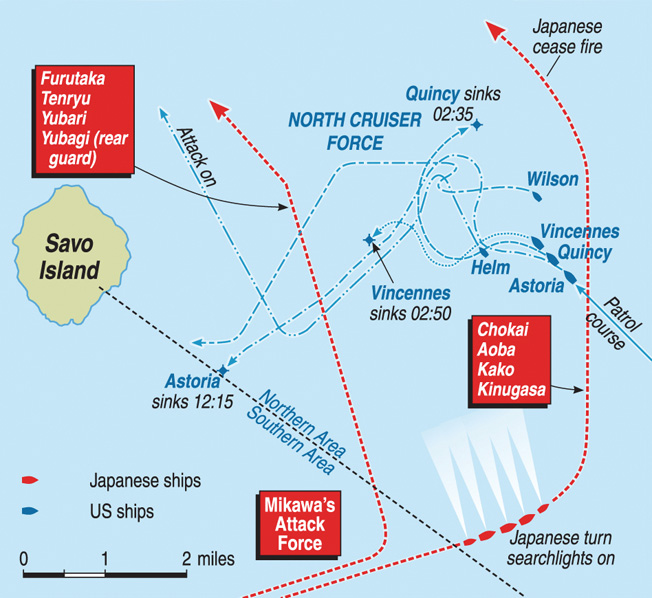

In showing King the memo, Captain George Russell simply said, “It isn’t good.” A naval battle had taken place off Savo Island near Guadalcanal. The American warships guarding the approaches to the landing zone on the island’s beaches had been surprised at night by a Japanese naval force. Four Allied heavy cruisers had been sunk. The nearby troop transports, still unloading precious supplies, were not harmed. However, they were being pulled back due to the imminent threat of additional attacks.

King would later consider the Savo Island battle the low point of the war. He said, “That, as far as I am concerned, was the blackest day of the war. The whole future then became unpredictable.” The last of the four cruisers to go down was the USS Astoria (CA-34). (You can more about the events of Guadalcanal and the Pacific Theater inside the pages of WWII History magazine.)

The History of the USS Astoria

Launched at the Puget Sound Navy Yard on December 16, 1933, the Astoria was the second ship of the New Orleans class of heavy cruisers. Among the last group of cruisers designed to be within the guidelines of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, the New Orleans class emphasized protection. Although slightly smaller than previous classes of “treaty cruisers,” the New Orleans ships featured thicker belts of side armor, increased protection around the magazine areas, and stronger deck armor. The Astoria as built had a main battery of nine 8-inch guns mounted in three turrets. Secondary armament consisted of eight 5-inch single-mount guns placed roughly amidships, four to a side, and eight machine guns. Wartime brought the addition of an assortment of antiaircraft guns mounted at various points around the ship.

The Astoria was no stranger to action prior to her participation in the Guadalcanal operation. She began the war cruising with the carrier Lexington on a mission to deliver planes to Midway Island. The task force was located about 420 miles southeast of Midway when Pearl Harbor was attacked. Subsequent months saw the Astoria involved primarily in carrier escort duties. She participated in the Battles of Coral Sea and Midway. During the latter battle, she briefly served as the flagship for Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher after the carrier Yorktown was abandoned. By late summer the Astoria was under the command of Captain William Garrett Greenman. The 53-year-old Greenman had taken over as the commanding officer of the cruiser on June 14, 1942.

Early August meant an exhausting stretch of long and difficult days for the crewmen aboard the Astoria. Since departing Koro Island in the Fijis on July 31, the crew had been in an almost constant state of readiness. The United States Navy was now on the offensive in the eight- month-old war with Japan, and the Astoria was in the thick of it. Since the landing of the Marines near Lunga Point on Guadalcanal and the smaller nearby island of Tulagi on the morning of August 7, the Astoria had helped fight off two Japanese air attacks and stood guard duty covering the approaches to the landing zone. More of the same routine was expected in the days to come.

Upon the initial approach to Guadalcanal, the Astoria had operated with her sister ships Vincennes and Quincy as part of a fire support group designated Task Group 62.3. When the fire support role ended, the cruisers became part of a larger screening group. Under the command of British Rear Admiral V.A. Crutchley aboard the cruiser Australia, the operations of the screening group centered on protecting the transport ships. Positioned off the landing zone, these were the ships that carried the Marines, equipment, and supplies that made up the invasion force. Their survival was vital to the success of the Guadalcanal operation.

During daylight hours the cruisers took up antiaircraft positions in close proximity to the transports. In the evening, the screening group guarded the sea approaches to the landing zone against the possibility of an attack by Japanese surface forces. To cover all possible points of entry to the area, Crutchley divided his screening force cruisers into three main groups; each was originally designated a name based on the lead cruiser of the formation.

Patrolling south and east of Savo Island, the Australia group comprised the heavy cruisers Australia, Canberra, and Chicago. The Australia group later became known as the south group of cruisers. The Vincennes group, later known as the north group, contained the Astoria and Quincy in addition to the name ship. Under the command of Captain Fredrick L. Riefkohl of the Vincennes, this group covered the east to west distance between Savo Island and Florida Island. Covering the eastern approaches to the landing zone were the light cruisers San Juan and Hobart. The latter area was deemed by Allied commanders as the least likely avenue for a Japanese surface attack. Each cruiser group was screened by two destroyers with additional radar-equipped picket destroyers stationed beyond the approaches.

The Night Watch

The night of August 8 began much like the previous night. At twilight the Astoria moved out of her daytime antiaircraft position and into her preassigned evening patrol area as part of the north group of cruisers. She took up position as the last ship in the column of cruisers about 600 yards directly behind the Quincy. The destroyer Helm was positioned 1,500 yards off the port bow of the lead cruiser, Vincennes. The destroyer Wilson occupied a similar position off the lead cruiser’s starboard bow.

The group patrolled the perimeter of a box that was roughly five miles per side. Turning 90 degrees in column to the right every 30 minutes, the group cruised at a speed of 10 knots, making the appropriate adjustments in time and speed to execute the corner turns as scheduled. Just before midnight rain squalls over Savo Island began to slowly move to the southeast, ultimately ending up between the north and south groups of patrolling cruisers.

The Astoria stood at condition of readiness two. Under this arrangement, normally used when the possibility of a surprise attack existed, the crew stood alternate watches of four hours’ duration. Two guns in each of the cruiser’s three 8-inch main turrets were manned. All nine guns were loaded with shells but were not primed. Lookouts scanned the horizon for enemy submarines, which were reported to be operating in the area. Captain Greenman was aware that a group of Japanese surface ships had been sighted earlier in the day some 400 miles away in the vicinity of Bougainville Island. Surely the picket destroyers or the south group of cruisers would sound an early alarm if and when the enemy surface ships arrived in the area.

The stroke of midnight ushered in the start of a new day—Sunday, August 9, 1942. The 12 to 4 am mid-watch had just begun aboard the Astoria. Men coming on watch settled into their positions across the cruiser. Weary sailors coming off watch set out for a brief four hours of rest before rotating back on duty.

Among those coming off watch was Seaman 2nd Class Norman Miller. He went below for a quick shower. Unable to sleep in his bunk, he decided to go topside. This was not unusual given the hot conditions that existed below deck. He ended up lying down on some life jackets near the 20mm guns that were located just above turret number three.

Lieutenant Commander J.R. Topper had begun his watch on the bridge as the supervisory officer of the deck just prior to midnight. A few minutes later Lieutenant (j.g.) N.A. Burkey, Jr., assumed his watch as officer of the deck. Among other sailors taking up their watch positions on the bridge were Quartermaster 2nd Class Royal Radke and Seaman 2nd Class Don Yeamans. Aboard the Astoria since June 1941, Yeamans was part of the quartermaster crew. Radke would serve as the lead quartermaster for the watch. Captain Greenman retired, fully dressed, to his emergency cabin located immediately adjacent to the pilot house.

Above the bridge, Seaman 1st Class Lynn Hager arrived for his watch at sky control. He put on his headset and tuned into the JV communications circuit. His first order of business was to test communications to the bridge. Everything appeared to be working properly. From the bridge came the following request: “Keep a sharp lookout on our own formation and all around.” He then moved over to his lookout station on the starboard side next to the 1.1-inch gun director, adjusted his binoculars, and began to search the horizon.

Deep below the main deck, Ralph Boone began his watch in the after engine room. The Machinist Mate 2nd Class had been aboard the Astoria since May 1940. He knew the ship well and soon went about his duties of conducting routine maintenance. In all parts of the ship, the men on watch went about their duties unaware that disaster lay less than two hours ahead.

Mikawa’s Bold Counterattack

The events that would lead to disaster for the men of the Astoria began to take shape shortly after the Japanese had learned of the American landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi. At about 2:30 pm on August 7, the Japanese heavy cruiser Chokai sortied from Simpson Harbor, Rabaul. Aboard was Rear Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, the commander of the newly formed Eighth Fleet. From the bridge of his flagship, Mikawa would personally lead an audacious counterattack. The bold plan called for a surprise night attack against American shipping in the Guadalcanal area about 675 miles southeast of Rabaul.

Mikawa had assembled a powerful force of five heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and a single destroyer. The attack force would enter the Guadalcanal area on the south side of Savo Island and move east to attack American shipping before departing the area by traveling north between Florida and Savo Islands. The journey south from Rabaul would take the Japanese force to the east of Bougainville and then southeast through a narrow passage in the Central Solomons known as “The Slot” that led directly to Guadalcanal. By the afternoon of August 8, the force had passed to the northeast of New Georgia on its final approach to Guadalcanal.

With scout planes launched in advance to reconnoiter the Guadalcanal area, the Japanese approached Savo Island at a high rate of speed. The scout planes reported the approximate positions of the two Allied cruiser forces positioned around Savo Island as well as the disposition of the transports. Just after 1 am on August 9, the force passed undetected near the destroyer USS Blue stationed northwest of Savo Island. Both radar and lookouts failed to spot the Japanese ships as they moved through the south passage around Savo and directly toward the south cruiser force. By this time Admiral Crutchley had already departed the area with the Australia for an urgent meeting of commanders off the landing zone.

“Strange Ships Entering the Harbor”

In a series of events that occurred in rapid succession, the Japanese force approached and surprised the unsuspecting cruisers on patrol southeast of Savo Island. Among the first American ships to sight the approaching Japanese was the destroyer Patterson. She immediately sent an emergency message over TBS (Talk Between Ships) radio, “Warning! Warning! Strange Ships Entering Harbor!” It was 1:46 am. Almost immediately, Japanese float planes dropped bright flares in the vicinity of the transports off Lunga Point, illuminating the cruisers Canberra and Chicago.

Then, the shooting started. Hit 24 times in less than five minutes, the Canberra was quickly turned into a blazing inferno. The Chicago, hit by a torpedo in the bow, failed to make contact with the Japanese cruisers as they sped past. Captain Howard Bode of the Chicago, left in charge of the south force by Crutchley, failed to send out a warning to Captain Riefkohl aboard the Vincennes.

At the approximate time of the Patterson’s warning message, Astoria’s Officer of the Deck Burkey was acknowledging a course change from the Vincennes over TBS radio. The cruiser group was turning slightly off schedule. As a result, the Patterson’s warning message was not received. A few minutes later Lt. Cmdr. Topper felt what he thought was a distant underwater explosion. Although he attributed it to a destroyer dropping depth charges, the noise was most likely torpedoes from the Japanese battle with the southern cruisers. Captain Greenman was not notified and remained asleep in his emergency cabin.

Lieutenant Topper was not the only one to hear underwater noises. In the after engine room, Machinist Mate Boone was in the process of checking the shaft alleys. The task, considered routine maintenance, was done to ensure that the shafts were properly turning. Boone suddenly heard strange noises in the water. He thought that there were problems with the shafts and immediately reported the sounds to the chief machinist mate who was in charge of the engine room. The chief promptly told him to check the shafts again.

At sky control, Seaman 1st Class Hager heard the distant sound of an airplane. Other lookouts soon reported hearing planes overhead. Hager twice reported this information to the bridge, and the latter report occurred at about 1:30 am. Lieutenant Arthur McLaughlin, the officer in charge of the six-man watch on duty at sky control, ordered sky forward and sky aft to keep a sharp lookout.

Upon hearing the reports of planes overhead, Topper immediately went to the starboard side of the bridge. Listening intently he could hear only the sound of the blowers that were located right behind turret one. He then went to the starboard window of the pilot house and looked forward and to the right. Nothing seemed amiss with the other ships in the formation.

Surprising the Allied Formation

The first indication that something was wrong appeared a short time later. Lynn Hager sighted a string of four or five flares from his post at sky control. He estimated the distance was 5,000 yards from the Astoria. A relative bearing of 180 degrees put the flares off the Astoria’s stern. Hager believed that the flares had been dropped from planes, and he reported his sighting to the bridge. At first the flares did not seem to be burning very well as they hung in the misty atmosphere. However, after lowering a short distance, the flares soon began to burn brightly. Lieutenant McLaughlin ordered Hager to report to the bridge the need to sound general quarters.

At about the time Hager’s report of flares reached the bridge, Topper yelled for Burkey to call the captain and stand by to sound general quarters. He then ran out the portside door of the pilot house and identified a string of four aircraft flares about 5,000 yards off the port quarter. It was about 1:50 am.

The gunnery department sprang into action at the first sight of the flares. Gunnery Officer Lt. Cmdr. William Truesdell, saw the flares just as a lookout reported the sighting of three Japanese cruisers. He immediately ordered all of the remaining main battery guns loaded and then requested the officer of the deck to sound general quarters. Sighting information was already flowing into the main battery plotting room where Lieutenant (j.g.) Dante Marzetta and his men were quickly calculating a firing solution. The enemy cruisers were thought to be 5,500 yards away at a target angle of 315 degrees.

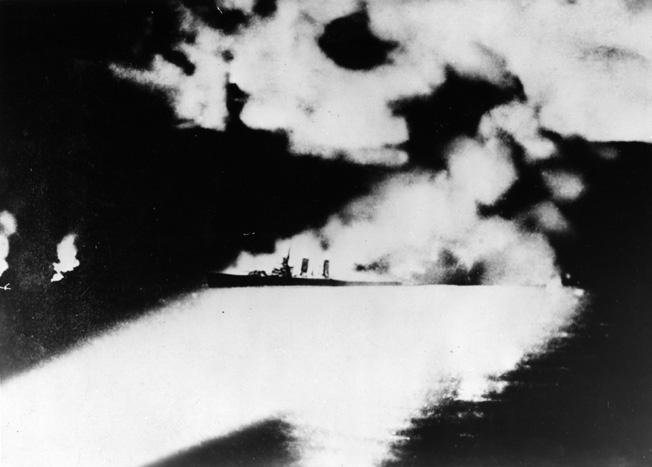

The Japanese cruisers, speeding northwest toward the Vincennes group, had their guns aimed at the American cruisers as early as 1:47 am. Lookouts aboard the Chokai could clearly see that the last ship of the American column, the Astoria, did not have her main battery turrets trained in battle positions. To the Japanese it appeared that the northern force of cruisers would also be surprised. With the command to commence firing given at 1:50 am, the Chokai immediately switched on her searchlight, illuminating the Astoria at a distance of 7,800 yards.

The Opening Shots

Within seconds the Japanese flagship’s first main battery salvo fell off the Astoria’s port bow, short and to the left. Following the lead of their flagship, other Japanese cruisers similarly opened fire against the Quincy and Yorktown. Less than two minutes later the Chokai’s second main battery salvo fell off the Astoria’s port side.

By this time Gunnery Officer Truesdell had requested permission to open fire. When no reply came from the bridge, he gave the order himself at about 1:53 am. The Astoria suddenly shook from the blast of an eight- or nine-gun salvo. Directed at the Chokai, all shots missed.

Confusion reigned aboard the bridge of the Astoria as the key officers of the watch were initially unaware that enemy cruisers had been sighted. Officer of the Deck Burkey, on the TBS with the Yorktown acknowledging a planned course change, had not carried out Topper’s request to call the captain. Quartermaster Radke observed a distant ship opening fire and immediately pulled the general quarters alarm without having the orders to do so. Noticing the absence of the captain, the junior officer of the deck, Lieutenant (j.g.) John Mullen rushed to get Greenman.

The fourth main battery salvo left the Chokai at about 1:53 am as the cruiser was almost 6,800 yards from the Astoria. Falling about 500 yards short, the salvo was correct in deflection. The Japanese gunners were close to having the Astoria’s number.

The USS Astoria Losing Guns

With the general alarm sounding, Captain Greenman entered the pilot house just as the main battery fired. Trying to grasp the situation at hand, he noted the flares in the distance and his ship being illuminated by a searchlight. He immediately questioned Topper, “Who sounded the general alarm? Who gave the order to commence firing?” Topper replied that he had not given either order. Concerned that the Astoria was firing on friendly ships, Greenman gave the order to cease fire. Truesdell immediately informed the bridge that he was firing at Japanese cruisers.

The gunnery officer requested urgent permission to resume fire. Captain Greenman looked up to see a salvo straddle the Vincennes off in the distance. Less than a minute later he saw the Chokai’s fourth salvo fall just short of the Astoria. He immediately gave the orders to sound general quarters and open fire. Greenman then ordered the ship to full speed and turned the Astoria slightly to port to better position her in relation to the targets and to keep clear of Quincy’s firing line.

The general quarters alarm sent sailors scurrying about the Astoria heading to their assigned battle stations. Men seemed to be racing in all directions on and around the bridge. Royal Radke stayed on the bridge as lead quartermaster, while Topper went to central station. Don Yeamans was in position on the port side pelorus, an extended point out from the bridge, with his headset tuned into the JV circuit. From his vantage point he observed the confusion on the bridge as the battle started.

He recalled, “Everyone was running around like the devil.” He turned to look out to sea. “I could see something on fire off in the distance.” The flames were likely the burning Canberra, whose men had already endured what the Astoria’s crew was about to experience. Also rushing to his bridge battle station was Ensign Thomas Ferneding. Aboard the Astoria for less than a year, Ferneding served as the cruiser’s signal officer.

At about 1:55 am, the Chokai’s fifth salvo hit the Astoria amidships, scoring at least four direct hits with 8-inch armor-piercing shells. The hits started fires on the boat deck and in the hangar area. The cruiser’s seaplanes, fully fueled in anticipation of an early morning launch, were quickly set aflame. The fires served as a target for Japanese gunners, who no longer needed the aid of searchlights.

The Astoria returned fire with a six-gun salvo. Fired from the two forward turrets, the shells fell short of their intended target. The two forward turrets now reached the limit of their turning radius on the port side and could no longer be brought to bear on the lead Japanese cruiser. The U.S. cruiser could now only return fire with turret three, which had temporarily lost power. A turn would later correct the situation and shift the firing to the starboard side.

Shortly after the Astoria fired her salvo, turret one was hit three times. Most likely coming from the same 8-inch salvo, one shell pierced the face plate while the two remaining shells hit the barbette. All personnel within the turret and barbette were killed. Another turn of the cruiser allowed her only available turret, number two, to fire its two guns.

“There was Just a Steel Wall Between Us”

The Astoria now came under extremely concentrated fire as additional Japanese cruisers directed their guns upon her. During a six-minute stretch beginning at 2 am, the Astoria was hit time after time by shells both large and small. During the onslaught the forward engine room was filled with smoke from a hit above and had to be abandoned. The number one fireroom was hit and all occupants killed. The main fire risers were severed, cutting off the water supply needed to fight the now raging fires amidships. An 8-inch shell pierced the protective shield around the number eight 5-inch secondary gun on the port side, hitting the ready service ammunition box and blowing a large hole in the deck. The fire in the hangar area now burned out of control. Most of the secondary 5-inch batteries eventually fell silent, with the majority of their crews killed at their battle stations.

During the hail of gunfire, a direct hit on the chart house killed the Astoria’s navigator, William Guy Eaton. The 42-year-old lieutenant commander was most likely killed instantly. Also felled in the same blast was Chief Quartermaster Leo Brom. The shell had hit just inside Don Yeamans’s position at the port side pelorus. “There was just a steel wall between us,” he recalled of the area. The force of the blast knocked him off his feet and ruptured his eardrums. The next thing he knew, two sailors were helping him up off the deck asking if he was okay.

Treating Casualties Under Fire

Ralph Boone never completed his routine maintenance. He was just about to start his second check of the shaft alleys when general quarters sounded. “I grabbed my lifejacket and flashlight,” Boone recalled as he raced to his battle station. At general quarters he would become part of a repair party that assembled in the mess hall. The room was located right above the after engine room.

Shortly after he arrived on station, the mess hall was hit by a Japanese shell. It caused a tremendous explosion and started a fire. Boone was not injured, but others around him were not so fortunate. Another machinist mate, A.L. McCann, was seriously wounded in the foot and ankle. Boone called out for a first aid kit. Ensign Hugh Davis immediately appeared with one in hand.

“I was preparing to put on a tourniquet when another shell hit nearby and destroyed the first aid kit,” said Boone, who decided to carry the wounded man to the after battle dressing area where he could receive better treatment. Passing through the crew quarters, he was stopped by Water Tender 2nd Class W.T. Duffy who had been on the JV phone. Duffy informed Boone that the after battle dressing area had been hit and was on fire. Unsure of what to do next, Boone gently laid McCann down into a bunk bed. He was soon recruited to help plug a shell hole one deck below and never saw the wounded man again.

In his position above the hangar, Seaman 2nd Class Miller had been seriously wounded in both legs. He was just about to fall asleep when the battle started. To escape his precarious position he was lowered by rope to the top of turret number three. Shortly thereafter, he was pushed off the turret and onto the main deck. With a life jacket on, he was lowered by rope into the water. Sometime later he was pulled aboard a life raft and was eventually picked up by a destroyer.

The Last Shots of the Astoria

The situation aboard the Astoria was getting worse. Throughout the stricken cruiser, a grisly scene was being repeated. Wounded men were clinging to life. Some had been badly burned, while others were missing limbs. The deck was slick with blood.

The bridge personnel still had control of both steering and engines. Communications lines were still open with central station, which was believed to be intact. There were no major fires reported below the main deck. However, the ship was on fire amidships, turret one was out, and most of the secondary gun batteries had been silenced. At about this time the engineering officer reported to the captain that there was serious trouble in the boiler rooms and that the ship had begun to lose power.

At this juncture the starboard side of the Astoria’s bridge was raked by gunfire, most likely from the heavy cruiser Kako. Among the bridge personnel who went down was the helmsman, Quartermaster 1st Class Houston Williams. Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class Julian Young, also wounded from shrapnel, made it to his feet and took the wheel. Just then the Quincy appeared off the port bow, a mass of flames. It appeared as though the ships would collide. Captain Greenman ordered a hard turn to port. Young threw the wheel to the left, and the Astoria passed safely astern of her sister ship.

The gunfire had also seriously wounded Ensign Ferneding in the right leg and heel. “I went to stand up and collapsed,” he would recall of the moment. Ferneding had been standing just inside the pilot house on the starboard side. Yeoman 2nd class Walter Putman propped him up against the bulkhead and gave him a cigarette.

After the hit on the chart house, Quartermaster Radke went about attending to the wounded as best he could. The captain’s orderly soon told him to relieve Young at the helm. The wounded boatswain’s mate was near the point of collapse. Someone needed to have control of the wheel to continue the zigzag movements that the captain had been ordering. Radke took the wheel and discovered that steering control had been lost. Steering was immediately shifted to central station. The speed of the Astoria was now seven knots.

Turret two trained out to the port side to take aim at a searchlight that was once again illuminating the ship. The source of the light was most likely the Japanese cruiser Kinugasa. With the main fire control system down, the turret fired under local control. These would be the last shots fired by the Astoria. The salvo missed the Kinugasa but scored a direct hit on the number one turret of the Chokai. The searchlight was soon extinguished. Enemy gunfire now began to subside. At last it appeared that the battle had passed by the Astoria.

Assessing the Damage

Above the bridge at sky control the situation was deteriorating as enemy gunfire exacted a heavy toll. The last order that Lynn Hager had received over the JV circuit from the bridge was to “Get those damn searchlights.” The communication circuit then went dead. Hager later reported, “Men up on the sky control kept dropping. They were scattered around the decks.” An officer left the position to try to bring some wounded men down to sick bay and returned reporting that the sick bay had been destroyed. Hager took off his useless headset and began to assist the wounded. When sky control was evacuated, he made his way down to the communication deck.

At about 2:15 am, the Astoria lost power. Moments later, Lt. Cmdr. Truesdell, coming down from the director high above, entered the pilot house and informed the captain that the ammunition clipping room directly above the bridge was on fire. With ammunition already starting to explode, he recommended that the bridge be abandoned. To those remaining on the bridge, it appeared that the entire ship aft of the main mast was a mass of flames. Greenman wasted no time ordering the abandonment of the bridge area. He passed word that all able- bodied and wounded men were to assemble at the forecastle, near the front of the ship. The captain himself took up station on the communication deck, just forward of turret two.

Truesdell stayed behind to direct the evacuation of the wounded from the bridge area. He searched all the upper levels to ensure that everyone was out. The able-bodied did the best they could to help the wounded down. Unable to leave under his own power, Ensign Ferneding was lowered to safety after a rope had been tied around him. Don Yeamans climbed down a ladder and made his way toward the front of the ship. Everything seemed to be on fire.

By 3 am, about 400 men, including many wounded, had gathered near the forecastle. Captain Greenman began to assemble the facts as to the status of his ship. It appeared that no serious fires existed below the second deck. The engine rooms were thought to be watertight. The ship had a list of three degrees to port, reason unknown. Large fires in the vicinity of the well deck, secondary gun batteries, and boat deck prevented access to the after part of the ship. Conditions near the stern were not known.

“Abandon Ship”

With all water mains ruptured, a bucket brigade was organized to attack the flames. It was hoped that the fires amidships could be beaten back. Sailors worked feverishly fighting the flames but with little success. The decks near the captain’s cabin became so hot that a plan to treat the wounded in that area had to be abandoned. Captain Greenman soon became concerned about the forward magazines. He ordered both the 8-inch and 5-inch magazines flooded. The flooding of the 8-inch magazine appeared to have been successful, but explosions heard in the vicinity of the 5-inch magazine cast doubt as to whether the flooding of that area worked. The captain became increasingly concerned that the 5-inch magazine would detonate.

Coming down from the bridge, Yeamans could feel the main deck getting hot. He knew that he was near one of the magazines but had no idea if it had been flooded. He thought that he heard someone yell “abandon ship” and quickly jumped over the side. It turned out that no such order had been given. He was picked up by the destroyer Bagley after spending three or four hours in the water.

At about 4:45 am, the captain decided it was time to abandon the stricken cruiser. The Bagley was requested by blinker to come alongside the Astoria’s starboard bow. Maneuvering into place, the destroyer nudged her bow right up to the side of the cruiser. Wooden planks, normally used for painting the side of the ship, were put in place to establish a crossing. Once the wounded were safely transferred to the destroyer, able-bodied personnel began to leave the Astoria.

As the Bagley pulled away, a flashing light was seen near the stern of the Astoria. The after portion of the cruiser did not appear to be on fire as first thought. The destroyer acknowledged the signal and then turned her attention to picking up survivors who were scattered about the sea.

Trying to Save the Astoria

Under the direction of Commander Frank Shoup, the cruiser’s executive officer, survivors had assembled near the stern of the ship. Commander Shoup had been forced to abandon his station due to intense fires. About 150 men, including about 30 wounded, gathered near the fantail. The 1.1-inch machine gun mounts on the main deck near the stern and turret three remained manned although the latter had no power. Looking forward, the men aft could see intense fires. They assumed that the entire forward part of the ship was ablaze.

Shoup ordered the wounded evacuated. Four life rafts filled with the most serious cases cast off from the Astoria’s stern in search of a destroyer. They were later picked up by the Wilson.

Commander Shoup then organized a bucket brigade. The group began to work at the starboard entrance to the hangar. Using buckets and 8-inch powder cans, they worked to beat back the flames. Their efforts were aided at about 3:00 am when a light rain began to fall. About an hour later the noise of a gas-powered pump was heard coming from somewhere near the forward part of the ship. Between 4:30 and 5 am, the bucket brigade had worked its way onto the well deck where progress was eventually blocked by an oil fire. About that time, the Bagley was seen departing near the Astoria’s bow and signaled by flashlight.

Taking stock of the situation, Shoup and the chief engineering officer, Lt. Cmdr. John Hayes, came to the same conclusion. The Astoria could be saved. They felt that there was a good possibility that the cruiser could even get under way on her own power. Shortly after daylight the Bagley pulled up close to the Astoria. A series of shell holes was observed just above the waterline on the port side of the cruiser. Captain Greenman soon reboarded his stricken ship.

Commander Shoup told the captain, “I think we can save her.” Greenman immediately formulated a plan of action.

After additional wounded were taken off the cruiser, a salvage crew of about 325 men began the effort to save the Astoria. The group consisted mostly of engineers, signalmen, and other specialists. Most of the officers also participated. The Bagley took off to transfer the remaining survivors to a transport just after 6 am. The effort to save the Astoria was soon in full swing. Three firefighting parties were organized to continue the work against the flames. Another group was assigned the grim task of collecting dead bodies and preparing the corpses for burial at sea.

Lieutenant Commander Topper, also the ship’s damage control officer, led a party below decks in an effort to determine the extent of the damage below the waterline. A 5-inch shell hole was found on the starboard side. It had been plugged and appeared to be holding. Several small fires were found and extinguished. The after magazines appeared to have been properly flooded. The group secured all watertight hatches and openings on the second deck and below.

Engineering personnel also went below to examine the various engine and fire rooms. Some of the rooms proved to be inaccessible due to debris or heat from nearby fires. Engineering Officer Hayes concluded that he could attempt to make steam from fireroom number 4 only. With both the forward and after batteries exhausted and the middle batteries destroyed near the well deck, all electrical battery power was found to be gone.

Explosions Below Deck

At about 7 am, the minesweeper Hopkins came to the area to provide assistance. An old destroyer converted to a minesweeper, the vessel transferred a gas-powered pump and hose to the cruiser to aid in the firefighting effort. A power cable was also passed over with the hope that it could be spliced into the Astoria’s system. Captain Greenman felt that the best chance to save the Astoria would be to get her into the shallow waters near Guadalcanal. He requested that his cruiser be taken under tow. Accordingly, the Hopkins backed her stern up to the cruiser’s rear so that a tow line could be passed between the ships. It took two attempts, but the Astoria was soon under tow. The Hopkins eventually was able to make three knots.

The destroyer Wilson arrived on the scene at about 9 am. Positioning herself off the Astoria’s starboard bow, she soon began to pump water into the fires. The stream continued for almost an hour. Around 10 am both the Wilson and Hopkins were called away. Captain Greenman was soon advised that the destroyer Buchanan would arrive to continue the firefighting effort. The transport Alchiba was also dispatched to take up the tow line

Although some progress had been made on the flames above deck, the fires below were increasing in intensity. A large fire was burning out of control in the wardroom area. Several small explosions below decks occurred, followed by a much larger one at 11 am. The larger explosion appeared to have originated below and just behind turret two. The Astoria’s list to port began to increase, first to 10 degrees and then to 15 degrees. The holes, which had been just above the waterline, were now taking in water. A failed attempt to plug them was made with mattresses and pillows.

Lieutenant Commander Topper was standing on the forecastle when he felt the rumble of another internal explosion. Looking over the port side he noticed yellow bubbles coming to the surface near turret two. He immediately ordered all personnel to leave the area and then rushed to report this information to the captain.

The Buchanan, now on station off the starboard bow of the cruiser, prepared to continue the firefighting effort. Captain Greenman made his way forward for a firsthand review of the efforts. The cruiser’s list was now increasing rapidly. The senior officers gathered to discuss the situation. Topper, Executive Officer Shoup, and Engineering Officer Hayes all felt that it was time to abandon ship once again. Captain Greenman readily agreed. Preparations were made for the Buchanan to move to the starboard quarter to take off personnel. All hands were ordered to make their way toward the stern of the ship.

Before Captain Greenman and his officers could make their way to the fantail, the Astoria’s list had reached 30 degrees. It became apparent that the cruiser was not going to stay afloat much longer. At noon Captain Greenman gave the order to abandon ship. Men began to jump into the water as the Buchanan stood about 300 yards distant. As Greenman and Shoup departed the ship for the last time, the list had increased to 45 degrees. The Astoria turned over to her port beam and began to sink stern first. Her bow rose slightly above the water, and she disappeared at 12:15.

Losing the Astoria, Winning Guadalcanal

One of numerous casualties suffered during the Battle of Savo Island, perhaps the most complete defeat of a force in combat during the proud history of the U.S. Navy, the USS Astoria was nevertheless a gallant ship whose crew labored long to save her. The sacrifice of one Australian and three American heavy cruisers off Savo Island, however, proved not to be in vain. Seven months later, the island of Guadalcanal was secured, and the long road to victory in the Pacific took a major step forward.

On July 27, 2005, the Clatsop County, Oregon, board of commissioners unanimously approved a resolution proclaiming August 9th of each year USS Astoria Day. Located in the northwest corner of the state, Astoria is Clatsop County’s largest city. The proclamation serves as a small but lasting tribute.

I have a letter my father wrote home after the battle. It was put in the Dallas, Tx newspaper and I will find it and send it to you for your files. It details his experience in the fight and is very interesting. He was blown into the water after one of the salvos from the enemy ships and was badly wounded. He was an enlisted man at the start of his tour but received a field commission to Ensign on the Astoria. He was, Charles E Kent Jr. from Richardson, Texas.

My uncle, Leland Charles Butler (Buddy) was aboard the Astoria when it was attacked. He was declared dead and his body was not recovered. Can you send a copy of your dad’s letter to

[email protected]? It would be so appreciated.

Thanks

My father was on the USS Astoria when it was attacked. He was one of the survivors.

My two older brothers Erwin (Jack) Frye & Edward (Eddie) Frye were both on the Astoria when it went down. Both enlisted in Salem, Oregon and were assigned to the USS Astoria (named after Astoria, Oregon)

My uncle Harry Dale Merrill of Gresham, Oregon served on board until 1939,then transferred to USS VINCENNES , part of the flotilla with Astoria and also sunk that night.

My Dad Thomas O. Storey served on the Nasty Asty during the Battle of Savo Island, he was a survivor.

My grandfather, now 96, served on the USS Astoria and was one of the survivor’s.

Amazing!

Two uncles served on the Astoria. Willis Darrell LaPaugh age 20 and older brother Forrest Delance LaPaugh approx age 26. Both from Elwell , Gratiot County , Michigan. We believe Willis was a gunner hit directly -dying immediately. We believe Forrest Delance sometimes called Mose, served below deck in the engine room. He was pulled from the water. Does anyone have anything they can add? We would be grateful.

My uncle, Leland Charles Butler (Buddy), from De Ridder, LA. was aboard the Astoria when it was attacked. He was a Gunner’s Mate 3c who was declared ‘lost at sea’ after the Astoria sank.

Does anyone have more information?