By William J. McPeak

For Europe, there was great news from Malta in August 1565. The Ottoman Turks had lifted their siege and made for home. The attempt to capture Malta was the boldest move by the Turks since they had overrun the island of Rhodes in 1522 and moved permanently into the eastern Mediterranean. Although they had failed to gain a foothold in the central Mediterranean at Malta, their threat was bound to rise again. In order to meet it, the Mediterranean European countries would need to unite. But could they?

Pope Pius V and the Holy League

The question was valid. The great European powers of the Mediterranean—namely the Kingdom of Naples, Spain, the Catholic papacy at Rome, and the Italian mercantile states of Venice and Genoa—were acting as they had for centuries, that is, distrustful and jealous of one another. They were disunited in dealing with their common enemies, which since the mid-15th century was really a single enemy, the Ottoman Turks.

Indeed, they were locked in the usual self-interest quandary, and they had little reason to trust one another. Spain was the military dynamo of Europe, long involved in Italian politics through its claims on Naples, and possessor of a New World empire. Genoa and Venice had been trade rivals for centuries, and Venice, although losing its Aegean and Adriatic Seas territory to the Ottomans in the previous century, was nonetheless paying a huge yearly tribute to the sultan in order to maintain its profitable trade with Islam. The papacy was fractious, too, with a say in everybody’s politics. Nevertheless, fiery old Pope Pius V was determined to unite all concerned against the Turks.

He had his work cut out for him. Talk of an alliance meant a commitment of troops and fighting ships. Yet the various powers were stingy with both, even though they all had a stake in standing up to Turkish might. The Pope finally took the initiative by forcing everyone’s hand. He put his considerable influence forward in declaring that he meant to fight the Turks, and the powers of the Mediterranean had better join in the formation of a Holy League.

Then, whether by espionage or freak accident, in September 1569 an explosion and fire in the great Arsenal Shipyard of Venice prompted the end of Turkish hesitation to confront formidable Venice. The great Sultan Suleiman had died in 1566, and the counselors behind his second son, the new sultan and profligate Selim II, knew that to hold power and keep a stable empire, this weak leader would need military successes. The Turks’ military goal became invasion of the central Mediterranean; Venice, particularly, was in the way.

The Pope’s will and events on Cyprus in 1570 convinced Christians that the time had come to unite in common cause. That year Turks began to move on Cyprus, a territory of Venice. By September Lala Mustafa, land commander at Cyprus, ruthlessly took the capital of Nicosia and, after terms had been granted, permitted the massacre of its 20,000 inhabitants. Venetian procrastination, brought on by Turkish deceptions of peace, came to an end, and Venice joined the Holy League near the end of May, promising a hundred galleys. It was none too soon.

Don Juan of Austria

The matter of an overall leader became a sticking point among the League members—the papacy, Spain, and Venice. No great noble of the League could overcome the rivalry of the others. So an outsider was needed, somebody who was above self-interest and could be an inspiring leader. Don Juan of Austria was the man.

He was young but tested as a military leader. Born in 1547, he had been named Geronimo and brought up in Spain at the order of his natural father, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (also Charles I of Spain). His half-brother was Philip II, the legitimate son of Charles and heir to their father’s Spanish possessions. In 1567, Don Juan, aged 20, became Philip’s ”General of the Sea,” having recently commanded 33 galleys in action against the corsairs of North Africa. More importantly, Don Juan put down the Morisco rebellion in Spain in 1570.

Behind the scenes, Don Juan was considered a figurehead, while older heads would devise the League’s battle plan against the Turks. It was not, however, in Don Juan’s nature to stand by—his elders just did not realize it. Don Juan had long dreamed of leading a high stakes confrontation against a determined enemy. Like many young firebrands, Don Juan saw himself as the Christian soldier facing a just fight, with the fate of southern Europe in the balance.

A Turkish Strategy Around Leponto

While the League was gathering ships and men, Selim’s commanders were organizing a great Turkish armada at Lepanto, the fortified port on the Gulf of Patras off the Adriatic. Their present strategy was to keep the Europeans separate. The sultan’s favorite admiral was the young and charismatic Piali (or Ali) Pasha, commander of the Cyprus invasion in the summer of 1570. He was ordered to harass the Venetian possessions—the islands of Zante, Cephalonia, and, particularly, Crete—in an effort to keep the Venetian Adriatic galley fleet extended and unable to regroup, thus rendering them unable to assist the League.

In addition to its own navy, the Turks had the fealty of Muslim and renegade pirate seamen or corsairs of the Greek peninsula and the North African coastline. These had been organized early in the century by an Albanian-Greek, the dreaded Barbarossa, who warred with the Italian sea powers and Spain until his death in 1546. His lieutenant and successor was the Greek corsair Admiral Dragut, the “Drawn Sword of Islam,” who had been the scourge of southern Europe before he was killed by a freak bullet ricochet during the siege of Malta. Leadership was now in the hands of a renegade Italian known as Uluj Ali, or Ochiali, a name meaning “Scabbyheaded,” given due to a bout with ringworm in his youth. Ochiali had his eye on a higher position in an Ottoman world where an ambitious man could go a long way. He therefore joined Ali Pasha in harassing the Venetian fleet. From strongholds at Algiers and Tunis, the corsairs raided France and Spain, creating a feeling of vulnerability in southern Europe. The Turks were confident that their window of opportunity was at hand.

Meeting at Messina

In March 1571 the League agreed to rendezvous in Messina on the east prominence of Sicily. Each ally had its quota of ships and men to assemble there during the summer. Sailing from Barcelona on his command galley (called a capitana), the Real, with a Spanish fleet of 35 ships, Don Juan moved down the west coast of Italy toward Messina. Along the way he grilled Philip’s former naval commander, now retired, Don Garcia of Toledo, on naval tactics. He also met enthusiastic crowds. Diplomats of Genoa, Venice, and the papacy saw him as “a young prince, and so desirous of glory … he will think more of gaining glory than of saving his galleys … [Still he is] anxious to find the enemy.”

At Messina by August 23, Don Juan surveyed his developing fleet. His Spanish galleys were new and well armed with heavy cannon, though disturbingly undermanned. Already present when he arrived was a combined squadron of 45 ships under papal leadership and commanded by the affable veteran Marcantonio Colonna, who had commanded the proto-League fleet that attempted to relieve Cyprus in 1570. With him as his lieutenant was his son Prospero. The gathering at Messina included 40 of the total galleys promised by Venice, which were lighter and more maneuverable. At the time these were sparring with the Turks under the leadership of the septuagenarian war dog, Sebastiano Veniero, governor of Corfu and Crete. Finally, Veniero received the orders from the Venetian Senate to pull back for Messina and join the League fleet.

With Colonna were three galleys of the intrepid Knights of Malta, by far the most experienced in naval warfare, which was their stock-in-trade. More than a Christian counterpart to the Muslim corsairs, the Knights Hospitalers of St. John had been Europe’s ever vigilant force, warring against Turkish interests since the Crusades. Throughout the 15th century the Turks had been repeatedly foiled by the Knights, who held the strategic island of Rhodes and guarded the eastern Mediterranean with a powerful fleet of war galleys and the latest gunpowder and fortification technology. The Knights, greatly outnumbered as they usually were, conditionally surrendered Rhodes in 1522, and then relocated westward across the Mediterranean to Malta, a strategic island bottleneck between Italy and Africa, the key to the western Mediterranean. This they successfully defended in 1565. Don Juan had a veteran Hospitaler, Don Juan Vasquez Coronado, as his ship captain. Among the several Knights who served as papal galley commanders was Mathurin Romegas, whose galley-raiding exploits against the Turks were legendary.

Other components of the assembled League armada were a half-dozen galleys each from Savoy and Tuscany and a seasoned squadron from Sicily. In addition, Spain had hired 24 Genoese galleys commanded by the shrewd Genoese admiral and businessman Gian Andrea Doria. He was the great-nephew of the legendary Andrea Doria, naval hero of the first half of the century. Now Doria, having lost several recent sea encounters, constantly advised caution in the matter of committing galleys to battle, especially his own. This was because galley raiding was foremost a commercial enterprise, while pitched warfare could be dangerously unprofitable. Finally, at the beginning of September, 60 galleys pulled back from Cyprus, headed by Agostino Barbarigo with old Veniero.

Ships of the Fleets

Turkish galleys were basically copied from those of Venice. The Turks had even copied the Arsenal in their galley-building facility on the Galata shore of the Golden Horn. Built by Venetian and Genoese renegade shipwrights and often captained by freebooting Venetians, Genoese, and Greeks, the Turks followed a bias within the philosophy of Islam against mechanism and technology. As a result, the Ottoman Empire paid for western naval and gunpowder technology. Along with the ships, cannon were forged by renegade European founders. The Turkish penchant for wanting things done quickly sometimes resulted in mediocre galley construction, using unseasoned wood, for example. Muslim galleys were often made with shallower drafts than their Venetian progenitors, making them more maneuverable.

There were smaller ships on both sides as well. The corsairs used galliots, smaller than the usual galleys, but with a similar shallow draft. These were very good for the sort of shallow-water raids for which the corsairs were well known. The corsairs and Turks used the galliots to quickly surrounding an enemy ship then board from all quarters. Galleys on both sides also used low-profile skiffs, shallops, or long boats trailing behind. When galleys were in close combat, these smaller trailing vessels were meant to surprise an enemy galley from the flank or rear. There was also the European fregata, a pinnace with sail and oars, used for scouting and ferrying men and messages within the fleet.

The Venetians had the biggest ships of all. Along with the lighter shallow-draft war galleys, the Venetians brought to Messina six galleasses, each towed by two galleys. These were distinct hybrid ships, not “great galleys,” the 270-ton galleys used for trading, as was sometimes speculated. The galleass was considered a “hybrid” stamp because it had the characteristics of the high-sided, cannon-rich fighting galleon, but also used oars. Below the galleass’s main deck was the principal gun deck; below that was the oar deck (seven slaves to an oar instead of the usual three to five). The galleass had an enormous hull with an elongated oval shape for heavy cannon placement and, like a galleon, three large masts of sail.

Galleasses were meant to be ordnance platforms with proportionately more cannon arrayed on the gun decks. More so than galleons, they anticipated the massive man-of-war fighting ships of the 18th and early 19th centuries. Their function was to carry some 30 full-size guns: five light pieces at the bow and stern of the main deck with the remainder of heavy pieces essentially ringing the bow, stern, starboard, and port sides of the gun deck. The six Venetian galleasses at Messina were innovations and carried more than 40 guns. Some 30-pounder cannon were stationed on the main deck with 50-pounders on the gun deck below. The Venetians hoped that such firepower would inflict severe damage on the lighter-gunned galleys of the Turks.

To Fight Or Not?

While the League fleet was gathering in Messina, all manner of European volunteers had poured in. Because some were raw recruits, Don Juan ordered basic training and weapon drills. The chief weapon used by European infantry since the late 15th century was the matchlock firearm known as the arquebus. As it proved its effectiveness, the arquebus became the predominant infantry weapon, while the crossbow and older longbow faded from general military use in the early 16th century. Naval arquebus tactics developed earlier in the century included not only the use of single shot, but also the use of buckshot to more efficiently sweep an enemy deck before boarding. Don Juan considered the number of arquebusiers for each galley—a complement of at least 100 soldiers. Because Venetian manpower was low, he asked that they accept Spanish and other Italian infantrymen to fill out their ranks. The basic tally of infantry was 20,000 Spanish, 5,000 Venetians, 2,000 papal levies, and about 3,000 European volunteers—a total of 30,000 infantrymen.

Now assembled, the League pondered its next move—to fight or not? The Venetians, with Cyprus and their trading empire in the balance, were joined by the papal commanders in voting for an open fight. But others, including Doria and the more cautious of Philip II’s advisers, tried to procrastinate. Don Juan, however, asserted his authority and further attempts at dissuading the enterprise were overruled—the die was cast. In a final counsel of war, Don Juan, ready to risk all, spoke with optimism: “I take it for certain that the Turks, swollen with their victories, will wish to take on our fleet, and God—I have the pious presentiment—will give us victory.”

On September 14, an early storm blew over the fleet—a bad omen for some who doubted of the wisdom of sailing so late in the season. It was an old Mediterranean nautical rule to postpone voyaging with the coming of the stormy autumn weather. All sailors had heard reports of fleets wrecked in freak Mediterranean storms. Nevertheless, on the 18th the League fleet set sail eastward, as Don Juan said, “to seek them [the Turks] out.”

There was division in the Ottoman camp as well. Ali was for fighting and the certain glory that would come from destroying the Christian fleet and laying bare the whole of Mediterranean Europe. Older, cooler heads wanted to think things out. Hamet, the commander of the Turkish naval base at Negropont, cautioned that no matter how militarily uncooperative the Europeans had been in the past, they would unite for such a critical confrontation. In fleet command of the Turkish left, Ochiali always considered the risk/reward factors, but also cautioned restraint. He had brought 25 galleys from Tripoli and meant to return with them. Mahomet Scirocco, commander of the Egyptian fleet that would form the Turkish right, thought it best to nestle under the fortifications of Lepanto and let the League come to them. Lepanto was protected by two fortresses on opposing sides of the narrowing headlands at the east end of the Gulf of Patras.

The troop commander of the fleet was Pertev Pasha, and he was emphatic that the infantrymen given him for the battle did not inspire his confidence, remembering as he did the decimation of his troops at Malta. Hassan, arbarossa’s son, played to Ali’s low opinion of the League, declaring that their history of disorganization would again be their undoing.

The Challenge of Intelligence

Spies tried to keep each side apprised of general ship movements, but neither fleet was sure of the other’s specific location. The League had crossed the Ionian Sea to Venetian Corfu by September 27, making 240 miles in 10 days, a notable feat. On the way, Don Juan had sent out Hospitaler Gil d’Andrade with four of the fastest galleys to scout the Turkish position. They discovered devastation from a recent Turkish raid on Corfu and news of raids against the island of Zante. Were the Turks just raiding and wintering at Lepanto or warming up to meet the League?

As September ended, both sides were still unsure of the other’s strength. The League was led to believe the Turks had only 160 galleys. A corsair captain, Kara Hodja, had painted a longboat black (a ruse borrowed from the Knights for raiding at night) and actually floated among the League fleet at anchor near Gomeniza to get an accurate count. His total was 50 short; he took galleasses for nothing more than show.

The suspense continued to build and the weather was fitful, reminding League veterans how easily nature could defeat them without the presence of Islam. But the weather was also effectively screening their advance. The League continued to crawl southward down the west coast of Greece toward the Gulf of Patras. Again Don Juan called for some scouting and sent Don Juan Cardona and 10 galleys of the Sicilian squadron to find the Turkish fleet. That day brought the arrival of a brigantine from Crete with news of the outcome of the siege of Famagusta, a fortress city on Cyprus. Although terms were decided, Lala Mustafa had treacherously seized the city, then mutilated and flayed alive the Venetian senator and city commander Marcantonio Bragadino.

“The Time for Counsel has Passed; the Time for Fighting has Come”

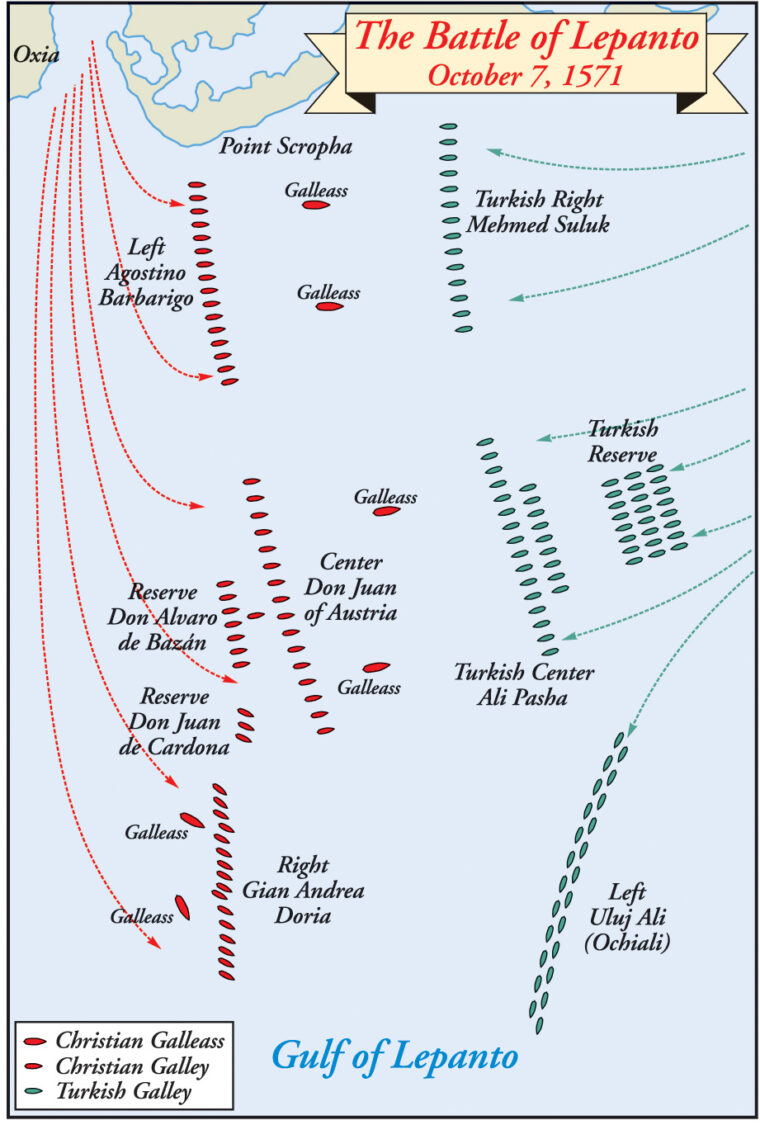

The League believed the Muslim fleet would approach them with their characteristic crescent-shaped battle formation (symbolic of Islam’s crescent moon flag). Such a formation could break a single line and indeed had undone the Europeans at Preveza in 1538. Muslim fleets used the ends of the crescent—the cusps—to engulf an opponent, so Don Garcia had suggested the League form three separate lines with space between to maneuver. This was accepted. The galleasses would be positioned a half-mile in front of the main fleet formation, two before each of the three lines, so as to fire into the passing Muslim ships heading for the main League line. Some 30 galleys would be held as a reserve behind the fleet. Thus, the Christian formation was cruciform.

Doria, seeing that the fight was inevitable, now came forward at the 11th hour with inspired tactical suggestions. Because the galley prow with its raised spur required the bow gunners to shoot at a high and ineffective trajectory, he suggested removing them to give point-blank accuracy to the cannon. Don Juan agreed. There were also far more arquebusiers than needed on the galleys. Doria suggested that because the galleasses were too high waisted for enemy boarding, massed arquebusiers should be placed on the galleasses’ decks to deliver volleys in coordination with the massed cannon. Don Juan again agreed and ordered 500 arquebusiers to the main deck of each of the galleasses.

The weather on October 6 was unsettled and the foes remained apart. Although Doria and a few others had once again remonstrated on the matter of coming to battle with the Turks, Don Juan cut them short: “Gentlemen, the time for counsel has passed; the time for fighting has come.” Before dawn on Sunday, October 7, he weighed anchor and moved due east through the Curzolaris Islands to deploy in the Gulf. Once there, the lines began to spread according to the battle array. No more than 100 paces were allowed between each ship so that no enemy vessel could slip between them. A watch phrase from the morning sermon was repeated as the time drew near: “No heaven for cowards.” Don Juan moved through the fleet in a fregata encouraging and exhorting, “My children, we are here to conquer or die. In death or in victory, you will win immortality.”

The Fleets Face Off

Dawn broke and the fleets came within sight of each other. The Turkish fleet was out of the haven of Lepanto and with the wind behind it, on its way to meet the League. The fleet comprised about 274 ships (some estimates are as high as 300): 215 galleys (as high as 235, probably including larger galliots) and regular galliots at the cusps of the long crescent formation. The right cusp neared the shallows of the Albanian coast while the left skirted the Morea (Peloponnesus) coast. At the center of the line rode Ali Pasha’s capitana, the Sultana, with 96 large galleys. Perhaps 25 to 30 of these with perhaps 10 galliots were just behind the front line as a reserve. On Ali’s right was Mahomet Scirocco with 56 galleys and perhaps 20 or so galliots. On the left was Ochiali with 63 galleys and over 30 galliots. This was significantly more enemy ships than the League commanders had surmised. Further, the Turks also had upward of 50,000 fighting men.

Ochiali had told Ali that the League was still in Messina. This misinformation, plus his cautions against outright battle, put him on ill terms with his commander. Ochiali did give Ali some important advice that went unheeded. Seeing the complex League formation, the corsair leader advised drawing back as a feigned retreat to lure the League into the narrowing Gulf, thus disrupting their formation. But Ali Pasha was too prideful, scorning any show of retreat as shaming the sultan.

At the League center with 64 galleys was Don Juan and the principal commanders: Veniero in the Venetian capitana to the left of Real and Colonna in command of the papacy at right. The generically heavier galleys in weight and firepower were of the lantern class, so named for the stern lantern display to mark a prime ship-of-the-line. These lantern-class galleys were for stability and served as a fulcrum in squadron maneuvering. About 25 lantern galleys were with the League: 10 concentrated with Don Juan (mostly to his right); one positioned at each end of the wings, three more at left, and four more at right on the wings. The left wing comprised 54 lighter and more maneuverable Venetian galleys with Barbarigo in command. Thus, the Christian left pitted the more flexible Venetians against the more maneuverable northern Muslim cusp; the Christian right had heavier firepower for dealing with the more populated corsair southern cusp.

On the League left closest to shore—at the point of greatest danger—was the lantern galley commanded by Marcantonio Quirini, who the previous month had outwitted the Turkish attempt to land on Crete and ran their blockade at Cyprus. On the right wing, Doria was in general command, but the principal combat commander was Hector Spinola on the capitana of Genoa. With him were about

50 Genoese, Venetian, papal, Neapolitan, some Spanish, and Savoyard galleys. Cardona and 10 galleys as a vanguard were to join him, but he stayed near the right flank of center to support the main fight there.

In the meantime, each galleass was towed by two galleys to the positions in front of the three lines. Those before the Venetian line were commanded by Bragadino’s kinsmen, the brothers Ambrosio and Antonio, who meant to avenge his foul death. In the rear was the most experienced admiral, the Spanish Marquis Santa Cruz, Alvaro de Bazan, who would assess the battle and send galleys to the points of greatest danger. Farther to the rear were some well-gunned galleons protecting the supply ships and acting as a boundary to catch any possible breakout of Turkish ships toward Italy.

The Holy League’s New Tactics

The Muslim armada came on with a shrill of cymbals, pipes, drums, and a guttural yodel (ululations) meant to unnerve their enemies. The clangor was punctuated by random arquebus shots. Stretched some 1,000 yards shorter than the Turk’s line, the League galleys and galleasses anchored ahead remained silent. They were not to attack until the order was given. Don Juan meant to get within point-blank range, firing only when close enough “to be sprayed by Muslim blood.” Meanwhile, League crews were finishing preparations that included spreading grease at points on the deck where the enemy would attempt boarding.

They were also checking a new innovation. The League’s galleys and galleasses sported the first checkered-design rope boarding nets (called ratlines) attached to the rigging both port and starboard that were meant to repel boarders. Crews were doing something extraordinary as well—unchaining all the Christian indentured and criminal galley slaves, handing them short swords and promising them freedom.

The all-important oarsmen who provided instant motive power were a strange mix of humanity, mostly galley slaves. They were captured enemy soldiers and sailors, sentenced criminals, debtors, and the poor. Free oarsmen were paid volunteers and were also drafted in times of need. For the Turks, it was a much easier equation to solve: They simply raided the islands and ports of the eastern and central Mediterranean, it not being unusual to carry off all of the inhabitants of a town to slavery. They also used volunteers. The slaves were chained naked three or five to an oar bench and lived in human waste for weeks at a time until making port, when all would be filed off for a short prison stay while the ship was washed down.

Suddenly, the wind fell away for the Turks, turned, and filled the League’s sails. Although four of the six galleasses reached anchor position, the two meant for Doria’s line were still laboring behind the main fleet as the wind came up, moving the fleet farther away from them. Then Don Juan raised the League flag—a giant crucified Christ. A great shout went up as all other League ships raised their flags and pennants. Don Juan ordered the Chevalier Coronado to steer for the Sultana, as the Sultana was already steering for the Real. Commanders usually stayed to the rear during the battle, but the test of combat was too strong an urge to keep these two apart. Don Juan fired a challenging shot from his big bow cannon so that Ali Pasha would know Don Juan awaited him. Some 14,000 Christian galley slaves in the Turkish fleet bent to their oars. It was near high noon.

A Bloody Duel: the Real Versus the Sultana

Because of the crescent shape of the Muslim line, Ali Pasha was not the first to discover the galleasses anchored like portable bastions before his fleet. The Turkish commander saw more than seven of his galleys sunk almost immediately as they crossed the galleasses’ line of fire. Massive broadsides erupted from either side of these ships, splintering Turkish hulls, and the sharp and unison crack of hundreds of arquebuses mowed down dozens of Muslim soldiers massed on the decks. The galleasses also harassed and damaged Turkish galleys that managed to pass them. Soon enough the Muslim ships were disrupted from their crescent formation by both the galleasses and their attempt to adapt to the League’s three-line formation.

The first fighting was at the League flanks, where the detached cusps of the Muslims outnumbered League ships. Scirocco’s shoreward line of shallow-draft Egyptian galliots worked inshore to turn the Venetian wing. Quirini at the end of that wing desperately staved off most, but not all, of these ships. With a timely reinforcement of 10 galleys from the ever-vigilant Santa Cruz to check the encirclement, Quirini, with his heavy galley as a pivot for the other galleys of the line, swept counterclockwise like a swinging gate to drive several galliots and galleys into the shore. Eight Egyptian galleys challenged Barbarigo’s Venetian capitana as the struggle for encirclement pitched back and forth. Barbarigo was mortally wounded by an arrow in the eye.

When the Muslim center reached face-recognition distance, the League center bow guns lit up the line with point-blank salvoes into the Turkish galleys. The League gunners were so practiced at gunnery that three of their shots were answered by only one from the enemy. Moreover, encumbered with their ram-prows, the Muslim shots usually sailed in high trajectories over their targets. Closer now, 75-year-old Veniero on his poop deck and wearing carpet slippers for comfort, made the first small arms shot from his ship, using a wheel lock blunderbuss. He fired at the Turkish bow gunners, then his men grappled with Pertev Pasha’s galley which was trying to follow the Sultana.

Then the commanders’ galleys came together, Ali Pasha’s ram chewing into Don Juan’s bow, thrusting it up into the Turk’s rigging. As in sea fights for centuries, crewmen along the decks of both vessels flung out grappling hooks to pull the two ships together. Arquebus volleys and showers of arrows were exchanged across the two decks. Turk infantry ran forward to board the Real but were blocked by the boarding nets. Simultaneously, 400 arquebusiers of the elite Sardinian regiment rushed onto the Sultana and were met by an equal number of Turkish infantry intent on flinging them back. Under a hail of arrows, the Sardinians’ initial push forced the Turks to their masthead, but they were parried back to the gunwales. The Sardinian attack and the counterattack of the Turks were played out a second time on the bloody decks of the Sultana. Finally, the Sardinians gave a third great lunge backed by Real’s armed galley slaves.

They pushed the Turks back to Ali Pasha’s poop deck, where the commander stood defiantly shooting arrows as fast as he could string them. From somewhere amid the constant crack of League arquebuses, a shot pierced his head. As he went down, a crazed Christian galley slave leaped forward and struck off his head. Jamming it down on a short pike, he took it back to the Real where it was hoisted up the mast. The soldiers and crew of Sultana saw it and quickly lost heart. Don Juan’s soldiers overran and looted the defeated galley. Among their prizes was the great green Turkish pennant with the name of Allah written in gold 28,900 times, supposedly a relic of Mecca that had never been captured in battle. The clash between commanders had lasted about an hour and a half. It was then 2 pm, and the battle at the center, with the added support of the League’s two center galleasses coming around, had been won by Don Juan. There were still the flank battles to settle, but the main concentration of Muslim heavy galleys had been at center and many were captured.

The Ottoman’s Right Routs

On the League left, six Venetian galleys had been sunk, but several of Scirocco’s galleys were sinking from the pounding being administered with merciless pleasure to the Turkish rear by the galleasses of the Bragadino brothers, who had come around to broadside the enemy. Then the League was suddenly given a gift. Some of the European galley slaves in Scirocco’s fleet had managed an uprising by passing smuggled files among them. As their chains dropped away, the slaves rushed the main decks and attacked from behind. Scirocco was killed in the hand-to-hand fighting that followed, his body falling overboard. He was quickly recognized, hauled out, and his head joined that of his commander hoisted up for all to see. Jarred by the slave attack and the death of their commander, the Muslim right folded, many ships going aground or purposely grounding so the crews could escape.

Ochiali Searches for a Prize

The battle on the League right was another story. As the fleets began to engage, Doria, like his old adversary Ochiali now before him, was more interested in maneuvering than fighting; his galley would emerge unscratched. Ochiali kept the galliots at the south end of the Muslim crescent reaching to encircle the League right. As he continued to extend his longer line, Doria tried to keep up, but soon he was overextending the distance between the center and right by 1,000 yards. Don Juan sent a message by a fregata ordering him to close up. But Ochiali’s bait had worked; he had all the room he needed to do what he intended. His intention, however, was not to take on the League center.

Having seen the outcome at the center, Ochiali, with typical corsair pragmatism, looked to the best advantage. Changing the course of the battle was untenable with the large League center still intact. The corsairs always attacked with the odds in their favor—or cut and ran to fight another day. But the sultan had ordered that no corsair commander should return home; instead, they were to proceed to Constantinople after the battle on pain of death. Ochiali could hardly go there empty-handed. He needed a prize to escape suspicions of not doing his utmost. In this he had conspired with half a dozen of his fastest galley captains to aid him. Clearly he was abandoning the rest of the Muslim left. He intended to use the gap between the League center and its right to swing around behind the Christian fleet for a surer purpose—to find a prize, take it, and make for safety.

Meanwhile, the League galleys on the right engaged the ships Ochiali had abandoned on the Muslim left. The Genoese capitana was carrying Alexander Farnese, Don Juan’s half-nephew, boyhood friend, and future general who had brought with him 202 comrade followers and 150 Italian soldiers. He enthusiastically led his men onto a corsair galley and quickly took it. Also on the right was the Spanish galley Marquesa with the regiment of the Marquis de Moncada, who was overall infantry commander. Among its companies was that of Captain Diego de Urbino with a young corporal named Miguel Cervantes, later author of Don Quixote. Although Cervantes had been sick below decks before the battle, he rose when the Turks came in sight. He volunteered for the dangerous duty of leading 12 soldiers in a long boat assault to board and surprise the enemy Muslim galley. He was wounded three times during the attack.

Other aid arrived to support the League right. The two tardy galleasses in the rear had come up and were delivering salvoes into the backsides of the corsairs grappling with the League right wing. Cordona’s 10 galleys joined the right and moved in to trap some 16 Muslim ships trying to turn out and escape along the Morea coast. But the price was high. Cordona’s ship alone had 450 of its 500 soldiers killed or wounded. The full complements of two of his galleys, the San Giovanni and the Piamontesa, would die to a man. To his relief came Don Juan himself, and soon the Muslim left broke. As on the Muslim right, some galleys beached on the coast so crews and soldiers could escape.

Ochiali had to move quickly to avoid the fate of his fellow commanders. He found what he wanted—a perfect trophy—the Maltese capitana that had come up from the reserve to aid the fight on the right wing. It was captained by one of the Order’s priors, Pietro Giustiniani, a personal enemy. Aboard with the prior were 30 Knights and 60 brother servants-at-arms. Ochiali attacked with seven galleys, surrounded the Maltese galley, and swarmed onto her deck. When it was over, Giustiniani remained alive, propped against the mast with five arrows in his body and two other Knights so severely wounded as to seem dead. Around them were their dead comrades surrounded by over 300 dead and dying corsairs; the Knights’ reputation was well founded. Ochiali took the galley in tow, but found the alert Santa Cruz had sent a reserve galley, the Guzmana, with Captain Ojeda to dispute the souvenir. Ochiali had the ship’s ensign, which was good enough, so he cut the towline and retreated with 13 galleys and some galliots, around 30 vessels total.

A Crushing Ottoman Defeat

It was now 4 pm—the sun was already red and sinking in a sea of wreckage with many more Muslim (over 25,000) than Christian dead (over 7,000, the Venetians suffering about 4,800). Ochiali had lost half his Algerian galleys but pounced on the lagging Venetian galley Bua to take back as the added physical proof of his loyalty. He was now dodging and weaving his way to Lepanto and then on to Constantinople to ingratiate himself and win a Turkish admiralty as the only important Muslim leader to survive.

More than 30 Muslim galleys and many of the galliots had been sunk. As many as 180 Muslim galleys—some ready for scuttling—had been captured. What was left of Turkish supply and reserve ships escaped with about 10,000 Muslim survivors. About 10,000 Muslims were taken prisoner, trading swords for chains to pull European oars, while about 12,000 Christian galley slaves were set free. Only 12 League galleys had been sunk, and though many had been damaged the battle was a resounding Christian victory. League firepower in cannon and arquebusier infantry had provided a great tactical advantage. Arquebus volley fire helped repel the typical Muslim infantry tactic of massed attack. Arquebusier close formations had effectively boarded enemy vessels. As a result, the Muslims lost nearly four times as many men killed—certainly partially to drowning. It was no piece of European propaganda but simple fact that in 1572 Ochiali, the new commander of the Ottoman fleet, ordered 20,000 arquebuses for his bowmen.

Sultan Selim was so enraged by the loss of so many ships and men that Sokolli, the Sultan’s Grand Vizier, needed all the tact he could muster to control the sultan’s threat to massacre every Christian in the empire. (There were at least 40,000 in Constantinople alone.) While Europe celebrated, Turkish officialdom succumbed to the fear that a League fleet would sail through the Bosporus and arrive at Constantinople’s door next spring. This plan was backed by Don Juan, but rejected by other League members. The Turks employed every human resource in the Ottoman Empire needed to rebuild the annihilated navy, if that was possible.

Yet, the old European rivalries and self-interests were back in play almost as soon as the battle was won. Even before the clash, greedy Venice was negotiating through the French with Constantinople for a peace, which was finally signed in 1573.

The regeneration of the Turkish navy of 1572 was actually only a mirage. It was surprising that the Turks floated a fleet of 150 galleys in the eastern Mediterranean in the spring of 1572, but it was a bogus fleet, a deception meant to save face and discourage the League’s frail unity. Such defeat-repair psychology was typical of the Ottomans. Given 16th-century naval technology, a full, even lighter-framed galley fleet could not have been battle ready in some five or six months’ time. Remaining conspicuously offshore, the sham Ottoman fleet was composed of unfinished ships of the smaller Algerine type made of green wood, carrying a minimum of inferior-cast cannon, and manned by skeleton crews and few soldiers. It spent the summer dodging a much-reduced League fleet. This was the devastating proof of the success of Lepanto on Ottoman ships and manpower.

As late as 1574, the still inadequate Turkish fleet would not commit to a substantial battle but paraded past safe ports to fling a rather safe challenge. The Turks stayed clear of naval confrontation with Venice for some 70 years. The victory at Lepanto had done its job, keeping the Turks from the western Mediterranean.

Taking one last command in the Mediterranean with the recapture of Tunis in 1573, Don Juan was thereafter a political pawn. A watchdog of Spanish interests in the rebellious Netherlands, he would die there unexpectedly of typhoid fever in 1578, only 31 years old. But his life and the victory at Lepanto were joined in epic history. Some 30 years after Lepanto, Cervantes, perhaps recalling that Don Juan had visited him as he convalesced on the Marquesa after the battle, summed up this decisive battle when his often incisive Don Quixote noted a perfect turn of phrase: “The best day’s work in centuries.”

Don Juan deserves much more fame than he has been given! He forged a historic change in the destiny of nations, stopped the Islamic invasion of Europe, in his twenties, an age when most of our children today are just “finding themselves.”

What could have been a follow up campaign against the Turks was stifled by the cited national rivalries, further complicated by Queen Elizabeth of England. The Queen desired trade relations with the Islamic world and because of the distance from them, had little to fear militarily. She had no desire to interrupt this arrangement, especially since it served as a counter to Catholic Spain which had tried to overthrow her. The mostly peaceful relations between England and Islam were to last for almost three centuries.