By Christopher Miskimon

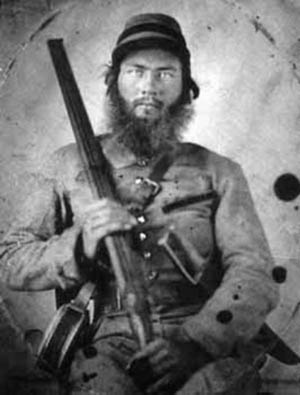

Coming upon the enemy’s rear guard outside the western Kentucky village of Sacramento, four days after Christmas 1861, Confederate Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest ordered his cavalry to advance. Ahead of them, a line of Union soldiers started to form, bayonets gleaming. Quickly, the bluecoat infantry formed its ranks and prepared to fight off the enemy cavalry, which had taken them almost unaware. Two lines of men formed the defense; the first line knelt, planting the stocks of their rifles firmly onto the ground, bayonets pointed out toward Forrest’s men. The second stood behind the first and aimed their weapons over or between the heads of their comrades. By the time they were ready, Forrest’s cavalry was a scant 20 paces away. The Union line presented a serious obstacle; the bayonets would impale horses and riders alike. Luckily for his men and animals, the wily and fierce Confederate officer had something other than an outright charge in mind. Almost as one, his horsemen raised double-barreled shotguns and fired at the enemy in a near-simultaneous volley.

The effect was shattering. Huge gaps were torn in the Union ranks. Each barrel had been loaded with 15 to 20 buckshot that crashed into the hapless infantry in wide, jagged patterns. One Confederate veteran later wrote in his diary that the carnage reminded him of “a large covey of quail bunched on the ground and fired into with a load of birdshot. Their squirming and fluttering on the ground would fairly represent that scene in that blue line of soldiers.” As many Union soldiers dropped to the ground dead or wounded, the effect on the rest of the unit was electric. Every man who was still standing turned and fled, many leaving their own weapons lying on the field among the bodies of their fellow soldiers.

The decimation of the Union infantrymen highlights the prime advantage of the shotgun: devastating close-range firepower. Not normally thought of as a military weapon, the shotgun has nevertheless found a useful place in the hands of soldiers worldwide. While its lack of range renders it nearly useless as a standard-issue firearm, when soldiers are fighting in close terrain in jungles or clearing enemy defensive works such as trench lines, many will reach for a shotgun whenever one is available.

The first shotgun widely used in warfare was the blunderbuss, distinctive for its flaring muzzle. This early weapon equipped European regiments from Great Britain, Prussia, and Austria. In 1781, General Sir John Burgoyne, famous to Americans for his role in the Revolutionary War, raised and equipped a Light Dragoon Regiment of the British Army and armed it with the blunderbuss. This early shotgun also served in contemporary navies, where its short-range firepower was effective in boarding actions.

The first shotgun widely used in warfare was the blunderbuss, distinctive for its flaring muzzle. This early weapon equipped European regiments from Great Britain, Prussia, and Austria. In 1781, General Sir John Burgoyne, famous to Americans for his role in the Revolutionary War, raised and equipped a Light Dragoon Regiment of the British Army and armed it with the blunderbuss. This early shotgun also served in contemporary navies, where its short-range firepower was effective in boarding actions.

Military use of the shotgun is generally considered an American phenomenon. While other nations have employed them in warfare, the American experience with shotguns is by far the largest and best documented. This is due to the widespread use of shotguns by civilians in North America, beginning with the colonial period. Shotguns have been used for hunting, self-protection, and recreation by generations of Americans. It is perhaps the quintessential utilitarian firearm, useful for hunting anything from squirrels and rabbits to birds and deer. The shotgun is relatively easy to use, requiring less precise aim than a rifle. This made it ideal for rural families trying to feed themselves. When these same Americans went away to war, their experience with shotguns went with them. Military shotguns soon followed.

Although not purposefully designed as such, the first common military shotguns in America were actually standard muskets charged with a load called “buck and ball.” This was a musket ball of the appropriate caliber for the weapon, with a few (usually three to six) buckshot added for additional firepower. This, in effect, made every firearm on the battlefield a shotgun. Since muskets had a smooth bore with no rifling, the addition of buckshot was easily accomplished and made tactical sense, given the short ranges at which armies fought during the Revolutionary War period. Buck and ball was popular with the American Army during the Revolution for the higher hit probability it promised.

Not surprisingly, the American affair with shotguns continued through the 1800s. Shotguns found use in the Texas War of Independence, where Colonel William Barrett Travis carried one at the Alamo. Americans also took them along when war broke out between the United States and Mexico in 1846. During the Civil War, buck and ball still found widespread use in units equipped with smoothbore muskets and cavalry units favoring purpose-built shotguns. With the advent of rifled muskets firing a bullet that spun to increase accuracy, separate shotguns were required.

While shotguns appear in a wide variety of barrel lengths, actions, and designs, a typical military shotgun of the 20th century is a firearm that, rather than firing a single spinning bullet like a rifle, instead projects a number of small usually round projectiles called shot. They gradually spread out after leaving the barrel. In a modern shotgun, at short ranges of 20 to 25 yards the shot will stay close together, most or all of them striking a man-sized target. Beyond this range the shot will disperse, until at long ranges of 75 yards and more a hit becomes a mere matter of chance. Shot large enough for use against humans is referred to as buckshot and comes in several different sizes. The most common load is 00 buckshot (pronounced “double-ought”), which typically has nine to 12 pellets of .32- to .34-caliber size.

The single- and double-barrel shotguns popularized in Western films saw occasional military use in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but this was most often because a soldier carried his own weapon rather than an Army-issued weapon. Some shotguns were issued as foraging weapons and doubtless some saw combat use. Most commonly used are pump-action and semi-automatic types commonly called riot or trench guns. While regular shotguns have barrels of 30 inches or so in length, military weapons for frontline use have their barrels shortened to 18 or 20 inches to make them easier to use in close quarters.

By far the most common caliber for a military shotgun is the 12-gauge, meaning that 12 lead balls the diameter of the barrel will equal one pound. This translates to roughly .72 caliber. While a few shotguns have been designed with detachable magazines like the modern assault rifle, most have tubular magazines that run under the barrel and hold between four and eight shells. Designs adapted to warfare are often modified to take a bayonet and have a ventilated hand guard on the barrel to keep the user from burning his hands if he has to use the weapon in close fighting.

The first major use of issued shotguns in the American military came during the Philippine Insurrection following the Spanish-American War of 1898. There, U.S. troops engaged in fierce close combat with Moros, indigenous tribesmen who fought a ferocious guerrilla-style war. Sometimes Moros would disguise themselves as civilians to get close to American soldiers before bursting upon them in hand-to-hand attacks with knives and swords. A shotgun was perfect for this sort of point-blank fighting. The U.S. Army purchased about 200 Winchester Model 1897 shotguns in 1900 specifically for use in the Philippines. This weapon, often called the M97, is probably the weapon that most people think of when they envision a military shotgun, although it was only one model among many that would serve the American military over the years. The Winchester M97 would go on to serve through the Vietnam War.

The shotguns in the Philippines were effective, as at least one officer who served there, John “Blackjack” Pershing, remembered when the United States embarked on its next major war. As commander of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in World War I, Pershing was determined to break the deadly stalemate in which the warring European nations had been locked since 1914. Shotguns were ordered to equip the American doughboys; the crowded trenches used by both sides were ideal territory for their short-range firepower. The Winchester was selected as the shotgun of choice, but that company was also producing other weapons for the American war effort and could not make enough M97s to meet demands. To fill the requirement, the Remington Model 10 was also adapted. Although experts still debate which was the better overall weapon, the two were essentially similar. They shared one real difficulty with the ammunition—many of the shell casings were paper, which quickly absorbed moisture in the trenches, causing them to swell. The solution was to switch to casings made entirely of brass.

Once in the hands of American troops, the shotguns quickly proved their effectiveness, and units requested more of them. Their compact firepower proved to be just what was needed to clear enemy trenches, giving rise to the “trench gun” and “trench broom” nicknames. Shotguns were a preferred weapon for raids and patrols and caused great fear among the Germans. One American sergeant single-handedly captured 23 German soldiers after bursting into their pillbox and firing just two rounds. In another instance, a massed German infantry assault was broken up by an American unit that had equipped 200 of its men with shotguns. The Americans poured buckshot into their opponents, leading one witness to recall: “The front ranks of the assault simply piled up on top of one awful heap of buckshot drilled men.”

Such effectiveness caused the Germans to take official notice. Newspapers decried the American use of the shotgun, comparing U.S. soldiers to savage Indians in the Old West. Others insinuated that the doughboys were simply inferior soldiers and could not use rifles accurately. The German government charged that the use of shotguns violated the Hague Decrees (ancestor of the Geneva Convention), which prohibited the use of any weapon “calculated to cause unnecessary suffering.”

Eventually, the situation became serious enough for the Germans to send a telegram to the U.S. State Department in September 1918 complaining that “the German Government protests against the use of shotguns by the American Army and calls attention to the fact that according to the laws of war every prisoner found to have in his possession such guns or ammunition belonging thereto forfeits his life.” The Germans threatened to summarily execute any American caught with a shotgun. At the time the telegram was sent, at least two U.S. soldiers had been captured by the Germans with shotguns in their possession, one from the 77th Division and the other from the 5th Division.

The American government denied that shotguns were prohibited by the treaty and threatened stern reprisals if a single American was killed for carrying one. The Germans took the threat to heart; there are no known instances of the Germans executing a captured American shotgunner. Since the weapon so frightened German troops, it is likely that some of its users were killed by their enraged captors on the battlefields, similar to the fate that often befell captured machine gunners or flamethrowers, two other weapons the World War I soldier had ample cause to fear.

A number of observers have questioned why Germany, the nation that introduced the horror of poison gas to the battlefield, so despised the relatively innocuous shotgun. The simple answer is because it worked. A man hit by a shotgun at close range was in serious trouble, since he would suffer up to nine .32-caliber buckshot wounds. If the shot spread out, several soldiers could be struck by one shot. Many decried the horrible wounds that shotguns caused, although a solid hit by a supersonic rifle bullet could be just as catastrophic. The war ended less than two months after the German telegram was sent. The Germans never sent a reply to the American response, and the argument quickly faded away. The shotgun remained in the American arsenal.

There the majority of them sat until the outbreak of World War II. The U.S. military’s weapons stocks were inadequate in almost every category, and shotguns were no exception. Some 30,000 shotguns had been purchased in World War I and what was left of these made up the entire supply. There were also shortages of rifles, and many National Guard units were given shotguns when their M1917 Enfield rifles were collected and issued to the regular army or sent to England under the Lend-Lease arrangement. Some of the weapons were hastily procured single-shot and double-barreled models bought because nothing else was available. As American forces entered the fighting in the Pacific, shotguns went with them; Winchester, Remington, Savage, Stevens, and Ithaca all made repeating shotguns for the war effort. They were perfect for the close jungle terrain the soldiers and Marines encountered. By war’s end, around half a million shotguns of all types had been purchased for military use.

While Army units in the Pacific used shotguns, the U.S. Marines are the most closely identified with the fighting shotgun. Tales abound of their exploits with the weapons and their ingenuity in obtaining them. The Marines often stole them outright from the arms lockers of naval vessels the night before an amphibious assault. At least one Marine unit issued its shotgunners birdshot so that they could blast Japanese carrier pigeons out of the sky. Trench guns also proved useful against snipers, who hid in the foliage of trees or other jungle growth. Even if the weapon did not kill the sniper, a few rounds of buckshot would shred the concealing branches and greenery around him, revealing whether or not he was dead. When Japanese soldiers tried to infiltrate American lines at night, shotguns were handy because the spread of the shot required less precision in hasty aiming. A shotgun-armed sentry with the 26th Marines on Iwo Jima once saw two figures in the dark casually moving into his perimeter. When they failed to respond to his challenge, he fired, dropping them both. Morning’s light revealed them to be enemy troops.

A lesser-known role for shotguns in World War II was in the training of pilots and aerial gunners manning machine guns for defense on aircraft. Shooting skeet, or clay pigeons, requires the ability to lead a target by aiming ahead of a flying object so that the shot will intersect its path. The shotguns used in training gunners were mounted on a pedestal similar to that used on actual machine guns so that recruits could learn as realistically as possible. While the aerial gunners had a low hit ratio, the tactic seemed to help the pilots. Former Ohio senator John Glenn stated that shooting shotguns helped him prepare for air-to-air combat.

The smaller conflicts of the Cold War saw just as much need for the shotgun. Again, many of them took place in places where the terrain was covered in jungle or thick growth. In the 1950s, the British Army found shotguns extremely useful in Malaya, purchasing several thousand Remington and Browning weapons. In a later study, the British concluded that the shotgun was highly effective up to 75 yards and within 30 yards was superior to assault rifles and submachine guns in hitting human-sized targets. Malaysian irregular troops were often armed with shotguns of various types.

The effectiveness of shotguns in jungle was not lost on the American troops in Vietnam. At first, leftover World War II models were used, but eventually new weapons were acquired. Leftover ammunition was used as well, although much of it had been rendered useless due to corrosion. By the 1960s, plastic-cased shot shells were available, although one account still favored the old brass shells, claiming that the plastic round would melt in the jungle heat, jamming the weapon. Besides infantry use, shotguns were widely used for base security. A shell-type round was also developed for the M79 40mm grenade launchers carried by U.S. troops. The ultimate Vietnam shotguns were the cannons of tanks firing “beehive” rounds that were loaded with thousands of needle-like flechettes.

In the first decade of the 21st century, the shotgun’s role has not diminished. American troops in Iraq use shotguns for combat and as breaching weapons to destroy door locks and hinges for entry into buildings. There is also increased use of more specialized munitions such as slugs, a solid projectile used in place of buckshot or as shells to hold tear gas or other riot control agents. Less lethal rounds containing rubber pellets or projectiles designed to incapacitate, nicknamed beanbags, are increasingly popular for use against crowds of rioters. These have given the shotgun a new versatility that makes it more attractive for operations in urban terrain where the objectives might be controlling civil disorder instead of taking lives. The U.S. military’s latest shotgun design is a compact model that fits under the barrel of the standard M16 rifle or M4 carbine, giving the user the option to unleash shotgun or rifle fire as needed.

The use of the shotgun in warfare dates back centuries. Particularly in the modern era, when small arms can achieve considerable range, the weapon fills no more than a specialist position for employment under only specific conditions. Still, when soldiers want devastating firepower at short distances, they often reach for a weapon their great-grandfathers would instantly recognize—the combat shotgun.

The so-called Philippine Insurrection should more properly be called the Philippine-American war. The Filipinos were in revolt against Spain when the US tipped the scales. The Filipinos declared independence while the US, having paid Spain $20 million for the archipelago, claimed ownership. It was a conflict between a nascent state and a replacement colonizer, and not an “insurrection” against lawful authority.

The Moros, so called by the Spanish (“Moors”), are a Muslim ethnicity in the south of the Philippines, and their fight against the Americans was tangential to the Fil-Am war.