by David A. Norris

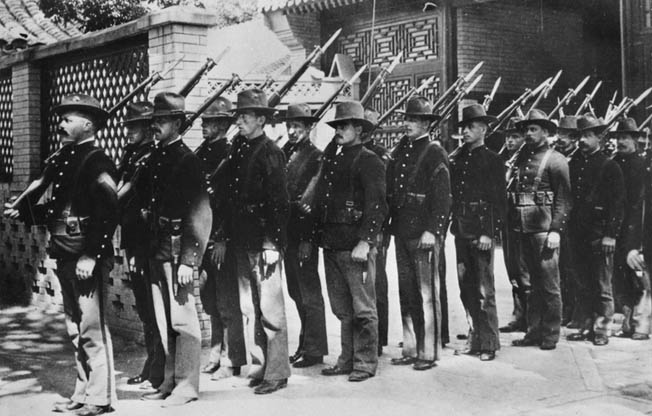

Captain John T. Myers’ detachment of U.S. Marines was far from home on July 3, 1900, in the thick of the Boxer Rebellion. Had it been daylight, their blue flannel shirts and wide-brimmed felt hats would have made them look a bit like American Civil War soldiers. A long way from Shiloh or Chickamauga, they stood atop what looked like a vision out of the tales of King Arthur, a mighty stone wall topped with battlements. Next to them were small detachments of British and Russian marines, waiting to charge a position held by Chinese troops. Myers’ men were part of one of the most surreal assortments of military forces ever seen. Never before had the flags of Japan, Germany, Russia, Great Britain, France, Italy, and Austria-Hungary flown with the Stars and Stripes over the same army. French colonial troops from Algeria and Indochina and the British Empire’s Sikhs, Ghurkas, and Bengal Lancers added even more variety. Such was the impromptu alliance of the marines, soldiers, and sailors of eight great powers that found themselves in China during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900.

Social upheaval, technical change, and international meddling were tearing apart the millennia-old Chinese Empire in 1900. Western powers expanding their empires in Asia turned their sights on China. Tottering under an inefficient government and militarily outclassed by European weaponry and steam warships, China lost several ports and pieces of territory through forced leases or outright conquest to Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and Russia during the 1800s. Even one Eastern power joined the fray. Japan, once more inward looking than China, embraced many Western ideas to build a formidable military. In 1894-1895, Japan won the Sino-Japanese War and gained control of Korea.

Bribery & Threats: The Way of Doing Business in China

Bribery and threats induced the Chinese government to grant mining, railroad, and other business concessions to foreign companies. The arrangements led to vast increases in unemployment. Chinese miners lost their livelihoods when their mines were given to European interests. A railroad from Peking to the coast threw thousands of river men and teamsters out of work. A severe drought in 1899 ruined crops and drove many peasants from their farms.

The Westerners who enforced their unwelcome presence in China enjoyed the privilege of extraterritoriality; that is, they were immune from Chinese laws and possible prosecution under the Chinese legal system. Foreign troops and police controlled railroad tracks, occupying port cities and other places on Chinese soil. Foreign missionaries were allowed to spread the Christian religion, bringing hope to many of China’s poor but alarming and offending traditionalists.

In the 1890s, the reformist-minded Emperor Kwang Hsu tried to strengthen his country through modernization similar to the path taken by Japan. The emperor’s accession to the throne was engineered by his aunt, the Dowager Empress Tsu Hsi. Starting as an imperial concubine, Tsu Hsi had used her formidable intelligence and political acumen to become the most powerful person in China. Unfortunately for the country, her considerable skills were employed in propping up the corrupt, inefficient, and conservative elite of the Manchu Dynasty. Opposing Kwang Hsu’s reforms, she had her nephew deposed and placed under house arrest.

Resentment For Foreign Influence Begins to Grow

Far from the imperial court and the foreign enclaves, resentment simmered across the countryside and villages of northern China against foreign influence and the hardships created by unemployment and famine. Angry and desperate Chinese flocked to a nationalist movement called I Ho Ch’uan, the Righteous and Harmonious Fists. Lashing out at change, their adherents attacked and killed missionaries and other Westerners and destroyed foreign businesses and property. Europeans scoffed at the movement, calling its followers the Boxers.

The Boxers mixed modernity with superstition. They mounted an effective publicity campaign with thousands of flyers and posters. They also claimed to their would-be followers that their special forms of martial arts and their ritual spells would deflect the lead bullets from foreigners’ guns. Demonstrations of invulnerability, arranged with rifles loaded with blank charges, convinced thousands to join them. The Boxers did not have uniforms but identified themselves by red sashes and armbands. Many of them spurned guns for swords, spears, and other traditional weapons.

The empress and the court watched the growing disorder with concern. There was no single leader of the Boxers who could be killed to stop the movement, which spread uncontrolled across northern China. Murders of missionaries and their families caused diplomatic pressure from the West that could easily turn into war. Even more worrying was the possibility that the violent new movement might blame the imperial family for China’s troubles and turn against it. Early in 1900, as attacks on foreigners increased, the empress revoked an earlier condemnation of the Boxers.

Peking: A City of One Million

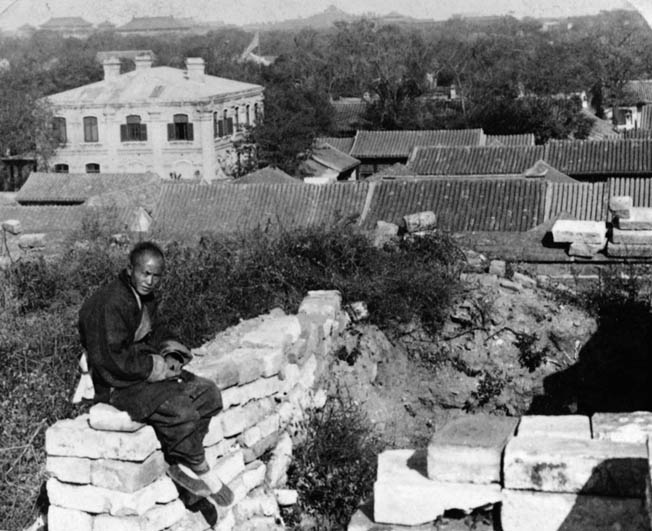

Peking (now Beijing) was then, as now, the capital of China. One million people lived in the city in 1900. Walls 30 feet thick and 20 feet high hemmed in the newer, southern section of Peking, which was called the Chinese City. To the north, the Tartar Wall, 40 feet high and 50 feet wide across the top, surrounded the older part of the capital, known as the Tartar City. This was the habitation of the nobility. Inside the Tartar City, within another set of walls, was the elite Imperial City. Inside the Imperial City was the inner domain of the imperial family, the Forbidden City. There, not even the highest aristocrats could enter unless invited.

Huddled between the Imperial City and Tartar Wall was the Legation Quarter, where foreign diplomats, merchants, and bankers lived. Most of the foreign establishments were arrayed along Legation Street, which ran east and west north of the Tartar Wall. The disused and shallow Imperial Canal, running north and south, bisected the area.

The British had the biggest legation, followed by the Russian and French compounds. The United States, Japan, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Spain, Belgium, and the Netherlands had smaller legations in the district. Each national legation was a combination embassy, residence, office, and social club for their ambassador (usually called a minister), staff, and visitors. Legations were not necessarily single structures. The British Legation was a walled complex covering three acres. The complex included the minister’s house, several office buildings, quarters for servants and employee, and a chapel, theater, bowling alley, surgery, and cemetery. Near the legations were several foreign-owned stores, businesses, and banks.

Inside the Bubble of the Legation Quarter

The diplomats and merchants in the Legation Quarter lived safely inside this bubble, but news about the slaughter of missionaries and the threats to their safety preyed on their minds. On May 27, on behalf of the Western community, British Minister Sir Claude Maxwell MacDonald asked for foreign troops. Although the army units of the great powers were too far away for timely help, marines serving aboard the Western naval vessels off the China coast could be deployed quickly. An emergency force was assembled from the warships of eight different nations off Taku at the mouth of the Pei Ho River 100 miles southeast of Peking.

Between May 31 and June 4, the scratch force of marines and sailors reached Peking. Among them was a detachment of U.S. Marines with a few American sailors from the battleship USS Oregon and the protected cruiser USS Newark, commanded by Captain John T. Myers.

Myers was born in Germany while his parents were traveling in Europe. His father, Colonel Abraham C. Myers, was a West Point graduate who also served as the Quartermaster General of the Confederate States.

Augmenting the international forces were some modern guns of varying degrees of effectiveness. The U.S. Marines brought an 1895 model Colt machine gun. Its firing system used a lever action device not unlike that of the Winchester and similar rifles but mechanized to fire 450 rounds per minute. The Marines’ Colt machine gun was mounted on wheels as if it was a miniature cannon. If these guns were not raised or mounted in some way, their gas-powered firing mechanisms gouged holes in the ground, spraying the gunners with dirt. This trait gave the gun its nickname of the Potato Digger. Another machine gun, a Maxim, came with the Austrian troops.

With the British was a Nordenfelt four-barreled, rapid-firing, 1-pounder gun. The Swedish-designed piece was originally made for naval use and was capable of piercing the boilers of attacking torpedo boats. As the Nordenfelt was prone to jam after every four shots, it was fortunate that the Italians brought another 1-pounder gun. The Russian contingent brought a shipment of 9-pounder shells, but their 9-pounder gun was accidentally left behind.

Boxers Appear Inside the City As Events Spin Out of Control

On June 5, insurgents cut the railroad to Peking. Boxers soon appeared in public in the city, inciting violence against the Westerners and provoking a mob to destroy a symbol of foreign influence, the Peking Racecourse. MacDonald got a message out to the Royal Navy’s Vice Admiral Edward Seymour, asking him to bring more reinforcements immediately. On June 11, Japanese minister Sugiyama Akira, on his way to a meeting with government representatives, was slain by Imperial Chinese troops.

Akira’s death was only the beginning. When hot-headed German minister Clemens von Ketteler shot a boy he believed was a Boxer, anger surged through the neighborhoods surrounding the Legation Quarter. On June 16, mobs attacked and burned churches, foreign businesses, and the homes of Chinese Christians.

On June 19, the Imperial government’s foreign office demanded that all the foreigners leave Peking. They were promised safe conduct, but the Westerners who crowded into the Legation Quarter placed little faith in the pledge. Stalling for time, they held out and waited to hear from Seymour.

Events spun out of control on June 20. An Imperial Army officer killed Ketteler when the German minister met with Chinese authorities. Boxer mobs opened fire on the foreign enclaves in the city, and they were joined openly by imperial troops. The Siege of the Peking Legations had begun. Trapped inside the Legation compounds were 473 foreign civilians, 407 military personnel from the eight nations, and approximately 3,000 Chinese Christians. One day later, the Dowager Empress announced a declaration of war against the foreign powers.

The British Legation Slated As A Last Stand

Chinese refugees who fled to the Legation compound were put to work building barricades of bricks and sandbags. The women trapped in the Legation sewed countless sandbags for the barricades. All sorts of materials went into them. Luxurious silk and satin tapestries, robes, and curtains were seized from Chinese mansions and palaces and the foreign stores surrounding the legations. They gave the sandbag barricades an incongruously bright and cheerful appearance.

To create a defensible perimeter, the outlying premises belonging to Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, and Austria had to be left out. Absorbed into the fortified areas were also parts of adjoining Chinese neighborhoods. A key section of the defenses was the segment of the Tartar Wall that ran from a ramp near the American Legation, east past the Imperial Canal, to a point near the German Legation. If enemy troops or Boxers possessed the high wall, they could rain their fire down upon the trapped Westerners.

The British Legation was selected as a fallback position for a last stand if the outer fortifications were breached. Their compound was surrounded by a 10-foot-high wall, and inside were several wells that provided pure water. Reflecting the early confidence of some of the British, brothers Nigel and David Oliphant, both of whom were civilian volunteers, went to work laying out a putting course on their legation’s grounds.

To strengthen the garrison, two bands of civilian volunteers formed. About 75 men, many of whom had previous military experience, were armed with spare rifles. Thirty-one of them were Japanese civilians. They stood watch and fought with the marines and sailors when needed. Another group of 50 men formed an irregular unit to guard the British compound and armed themselves with a motley variety of hunting weapons including an elephant gun. They affixed butcher knives to their weapons and so became the Carving Knife Brigade.

How von Thomann Lost His Command

The senior military officer present, Captain Eduard von Thomann of the Austrian cruiser Zenta, took command of the Legation forces on June 21. Von Thomann made a potentially fatal blunder on June 22. Hearing a rumor that the American Legation was abandoned, he ordered all international forces to retreat into the British Legation for their final stand. Amid the confusion, it was some time before it became clear that the captain had panicked and that the American Legation was still safe. Fortunately, the enemy did not realize the fatal advantage it had in its grasp. The defenders returned to their lines, losing only a little ground.

After this near disaster, all confidence in von Thomann was lost. As the senior minister in Peking, Great Britain’s Sir Claude MacDonald assumed military command with the consent of the Western ministers and officers. MacDonald was a capable leader with considerable military experience with the British Army in Egypt and West Africa. Herbert G. Squiers, secretary of the American Legation, served as MacDonald’s chief of staff. Squiers was a former officer of the 7th U.S. Cavalry with service against the Sioux in their 1890 uprising.

There was little time for MacDonald to settle into his new responsibilities. Some of the neighboring Hanlin Academy buildings were demolished to prevent the enemy from using them as firing positions. On June 23 and 24, the Boxers set several fires in the remaining buildings of the Hanlin Academy, the Mongol Market, and other locations adjoining the defenses. They hoped that the flames would spread into the international compound. Several of the legations had their own small fire engines, and with the help of bucket brigades fires inside the defenses were brought under control.

The Train Gamble

Outside the Legation Quarter, only one lone island held out against the Boxers. About two miles away, Bishop Auguste Favier led a small band of priests and nuns at the Peitang Cathedral, inside the walls of the Imperial City. About 3,000 people, mostly refugee Chinese converts, were packed into the cathedral precincts. For defense, there were 30 French and 11 Italian enlisted marines with one officer from each country.

Private John W. Tutcher of the U.S. Marines was shot in the right knee on June 24. Back on duty at the Tartar Wall, he was killed on the night of June 30. Tutcher and the other Americans who fell during the siege were buried on the grounds of the Russian Legation. None of Tutcher’s comrades could be spared from their posts to attend his brief funeral. His body was wrapped in a flag, but there was no coffin. An American, Mrs. W.S. Woodward, wrote that “a large Russian” [evidently a marine] interrupted the burial, saying in broken English, “He no comfortable.” The Russian stepped into the grave, patted and raised the earth under Tutcher’s head, and rearranged his arms and hands. “We brothers. We fought in the war together,” he said.

Cut off from the outside world as they were, it was just as well that the besieged foreigners at Peking did not know that their would-be rescuers were in little better shape than they were. Seymour set out on June 10 with a multinational relief force of about 2,200 men. To cover the roughly 100 miles from the sea to Peking, Seymour embarked his men aboard four trains at Tongku, the railroad’s coastal terminus. Armored flatcars carrying troops and machine guns or cannons were placed in front of each locomotive.

It was a gamble going by train through territory under Boxer control. Seymour mistakenly thought the train trip would be quick and that the imperial troops would side with them against the insurgents. Instead, the troops openly sided with the Boxers. Progress was slowed by constant repairs to tracks torn up by the rebels. When they reached Lang Fang about 40 miles from Peking, the trains could get no farther. Unable to proceed, Seymour tried to retrace his steps. The trains made slow progress until June 19, when they reached a bridge too badly damaged for them to cross. Seymour abandoned the trains and started following the Pei Ho River toward Tientsin, a major city at the intersection of the Pei Ho and the Grand Canal about 30 miles from the coast.

A Younger Herbert Hoover Trapped in Tientsin

As Seymour headed toward Tientsin, the Boxers captured the Chinese districts of the city. Then, as in Peking, insurgents and imperial troops laid siege to the city’s Western community.

A future president of the United States, Herbert Hoover, was among the Westerners trapped in Tientsin. About 2,300 troops, marines, and sailors, mostly Russian, faced Boxers and imperial soldiers more than 10 times their number. Hoover, as a civil engineer, was in charge of designing fortifications. Emptying the city’s warehouses, he directed the construction of a two-mile-long barricade made of bales of wool or camel hair and bags filled with peanuts, sugar, and rice.

Hoover’s wife Lou volunteered to nurse the wounded and tended some dairy cattle. Carrying a .38 pistol, she bicycled throughout the defenses each day on her errands. She had at least one close call when one of her bicycle tires was punctured by a Chinese bullet.

Aboard the foreign warships, the Allied commanders waited, not wanting to land troops and provoke more violent reactions. But worries over Seymour’s force and the fate of the foreigners in Peking and Tientsin led them to make plans to secure the route to Tientsin and Peking. To hold Tientsin it was necessary to take several Chinese forts that protected the Pei Ho River near Taku, close to the sea.

“A Hot Time In the Old Town Tonight”

After a flotilla of Western gunboats reduced the Taku forts, their relief force reached the International Settlement at Tientsin on June 23. Herbert Hoover later remembered his joy at seeing the U.S. Marines march into the foreign section as their buglers played “There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight.”

With Tientsin’s foreign quarter safely in hand, the next step for the Western forces was saving Seymour. By June 22, Seymour’s column had fought its way as far as Hsiku, only about six miles from Tientsin. There, the troops seized one of the country’s largest arsenals. The Hsiku Arsenal was a good defensive position and was packed with everything from modern Krupp guns to millions of rounds of rifle ammunition. Fending off counterattacks, though, left them burdened with wounded. Seymour elected to wait for relief. On June 26, a relief force of Russian, British, and other nationalities reached them, and they returned together to Tientsin. Among the British on the relief expedition was Commodore David Beatty of the HMS Barfleur. Beatty is better known as the vice admiral who commanded a fleet of British battlecruisers at the 1916 Battle of Jutland during World War I.

Up until mid-June, the United States had considered that dispatching marines from its warships off the Chinese coast was a sufficient response to the emergency in China. With the widening violence, Washington deemed it necessary to send troops as well. The Spanish-American War had given the Americans a launching point in the Far East with the acquisition of the Philippines from Spain. Large forces were tied up fighting the Philippine Insurrection, but the 1,300 men of the 9th Infantry were ordered to China. They began arriving in Tientsin on July 11.

Tientsin Falls With Heavy Casualties

With the arrival of the Americans and more foreign troops, the Allied commanders made a concerted attack on Tientsin to root out the Boxers. After two days of intense fighting on July 13 and 14, the city fell. Casualties were heavy as the imperial troops and Boxers put up heavy resistance. Among the dead was the commander of the 9th Infantry, Colonel Emerson H. Liscum. A Vermont native, Liscom was breveted a captain during the American Civil War after the 1864 Battle of Bethesda Church.

Even with Tientsin under control and Seymour’s expedition safely returned, the relief of the Peking legations seemed impossible without waiting several weeks to assemble a much larger force.

The allies in the Legation Quarter continued to hold off the attacks and wait for help. Their spirits held up well, and they eased their anxiety about the arrival of the rescue force with jokes about Admiral Seen-no-More.

Disaster threatened on July 1. The U.S. Marines were holding their position at a bastion on the Tartar Wall near the American Legation. Their line was poorly chosen, as it ran behind a barricade along the east side of the bastion, leaving the rest of the bastion’s surface undefended. Chinese forces seized the west end of the bastion and settled in behind improvised fortifications. Thus, each side held one of the two ramps giving access to the walls at that point. Unlike those firing at some areas of the defenses, the snipers peppering the marines on the wall were persistent and highly accurate. One advantage was that the rear of the American line was protected by German forces inside another barricade across the wall.

A Night Attack to Destroy The Tower

During the night of June 30-July 1, the Chinese brought up three field guns to their own barricade facing the Germans. The German detachment, a dozen men commanded by a corporal, withdrew from the wall. The German retreat exposed the marine barricade to enemy fire from the rear. Captain Myers ordered his marines to withdraw to their legation. After a quick consultation with Squiers and U.S. minister Edwin H. Conger, Myers saw that the wall must be held at all hazards. After about 15 minutes, Myers retook his old position on the wall with the aid of some Royal Marines.

Although the German position was lost, the Americans intended to hold their line on the wall. That night labor parties made up of refugee Chinese Christians built new barricades to shield the Americans from enemy fire.

By dusk on July 2, the Chinese had built a new wall beginning at the right flank of their barricade across the open surface of the bastion. At the far end, the new wall nearly touched the American fortification. With the protection of darkness and the new barricade, the Chinese worked on a new tower from which riflemen could pour an enfilade fire into the Marines’ line. The tower was “so close that one could touch it with a stick from the south end of the American barricade,” wrote Nigel Oliphant.

Myers Loses Men During a Boxer Rebellion Pushback

Myers planned a night attack to destroy the tower. Between 2 and 3 am on July 3, the tower was almost finished and the enemy were “amusing themselves throwing stones into our barricade.” With Myers were 14 U.S. Marines, 15 Russians, and 26 British marines and volunteers, including Oliphant. A civilian bank employee, Oliphant was a veteran of the British Army who had served in India.

Myers sent the Russians from his right across the bastion to the Chinese-controlled ramp on the opposite side. The Americans and the British would attack from their left, keeping on the south side of the new covering wall. Oliphant recalled the combined force “standing two deep on the ledge at the bottom of the barricade, which just enabled us to get out heads and arms over the top.”

Dropping down from the 10-foot-high barricade, Myers and his men rushed past the tower and hit the Chinese barricade on the far end of the bastion. They drove the enemy away from the barricade and the tents they had pitched behind it on the wall. Myers secured a much more tenable position by pushing the Chinese back more than 100 yards to their next barricade on the wall.

Myers was wounded in the attack, and “two of the best men” in his detachment were killed. At first, Myers’ wound, which was caused by an iron spear, seemed minor. But septicemia set in and he was hospitalized at the Russian Legation and relinquished command of the Marines to Captain N.H. Hall.

The Chinese Bring In Their Jingals

The Boxers and imperial troops tightened the siege. Snipers and artillery gunners found new firing positions atop sections of the wall or high buildings overlooking the legations. With the wide mix of ancient and modern weapons used by the Imperial Army and the rebels, the defenders were liable to have anything from arrows to Krupp shells slamming into their works. Some Boxers threw bricks and stones over the Legation barricades. Others set off firecrackers for the psychological effect of ratcheting up the noise and tension during attacks.

Among the Chinese weaponry were picturesque oversized muskets called jingals. Sometimes made as oversized copies of Western long arms, jingals could be more than six feet long with a .75-caliber barrel. The weapons were so heavy that they had to be balanced on a stand or swivel and fired by a two-man crew.

Nigel Oliphant wrote that in making his rounds on July 2 he was “much annoyed by a man who kept firing a jingal loaded with copper cash [small coins, with square holes in the center] and odd bits of metal onto the roof of the hospital.” Oliphant noted that although “the explosion and the flash both seemed to be close to us” the man firing the jingal was “really on the opposite side of the Mongol Market, and thus 300 yards away.”

On July 5, David Oliphant was mortally wounded by an enemy sniper while helping cut down some trees between the British Legation and the Hanlin College. Three days later, a shell killed Captain von Thomann. By an odd twist of fate, the Austrian captain had not originally been on a military assignment. He had come to Peking for a holiday and had been caught in the fighting when the rebellion broke out.

Their lack of heavy artillery constantly worried the defenders. When the Italian one-pounder piece ran low on shells, Gunner’s Mate Joseph Mitchell of the USS Newark manufactured new ammunition. Pails full of spent enemy bullets were gathered up and handed to Mitchell. Using discarded shell casings, he melted the bullets to make new projectiles. The little gun was kept busy, but as Nigel Oliphant wrote, “Such a little toy can’t do much. Oh! For a single 12-pounder.”

Mines Detonate Under the French Legation

On July 7, Chinese workers digging a trench dug up an old muzzle-loading bronze cannon barrel left by the Anglo-French forces during the 1860 fighting in Peking during the Second Opium War. Gunner’s Mate Mitchell and Herbert Squiers cleaned up the old relic and restored it to firing condition, mounting it on a spare Italian carriage.

Gunners found that the cannon could fire improvised grapeshot. They got a lucky break when they discovered that the useless Russian 9-pounder shells were a perfect fit for the new gun. To fire the modern ammunition in the antiquated cannon, the shells were taken apart and the charge and projectile rammed separately down the barrel. When fired from the Student Library in the British Legation, the gun’s vibrations shattered most of the windows.

Mitchell’s makeshift piece had many names, with some calling it Old Betsy and others, the Dowager Empress. Most of all, as it had a British barrel, an Italian carriage, and was fired by American gunners using Russian shells, it became known as the International Gun.

While the foreigners kept close watch from their barricades, underneath their feet grew a new menace. Chinese prisoners revealed that coal miners had been brought in to dig underneath the Legation Quarter. The Chinese converts, who had been pressed into service as laborers on the fortifications, dug deep ditches as countermeasures.

Despite the countermeasures, on July 13 two mines exploded under the French Legation. Two French sailors were killed in the blasts, which destroyed two buildings and some of the barricades. A large number of Boxers and imperial troops who were too close to the site of the explosion were also killed.

20,000 Troops To March on Peking

Arthur von Rosthorn, the Austrian chargé d’affaires, was trapped up to his waist in rubble from a collapsed roof and walls after the first blast. The second blast freed him by throwing him clear of the wreckage. Much of the property was abandoned, and the defensive line was pulled back to a trench the French had prepared as a fallback. German forces repulsed a simultaneous attack, killing a number of attackers in a bayonet charge across their legation’s tennis courts.

Until rains came in July, water was rationed in the Legation. To the stench of unburied casualties and horses was added that of the besieged themselves. There was not enough water to wash clothes, or to bathe. When rain came at last, wrote Oliphant, it “never seems to cool the air, but, instead, creates a nasty damp, muggy atmosphere.” A plague of flies drawn by the dead human and animal bodies made everyone miserable. “At night the ceiling and the tops of the mosquito-nets are black with the vile insects, and when a big gun goes off they all rise with a buzz loud enough to wake any but a heavy sleeper,” wrote Oliphant.

Far from Peking, false reports reached the outside that the Boxers had captured the Legation Quarter and slaughtered everyone inside. Newspapers printed alarming estimates that half a million foreign troops and two to three years would be needed to quell the fighting.

As the phony news stories spread, the allied powers assembled a larger force to march on Peking. Command went to Brig. Gen. Sir Alfred Gaselee of Britain. Of the 20,000 troops, 2,500 men made the U.S. contingent the third largest next to the Japanese and Russians. Additional French, British, German, Italian, and Austro-Hungarian troops joined the force. Maj. Gen. Adna R. Chaffee, a veteran of the American Civil War and the Apache Wars, commanded the American units: the 9th and 14th Infantry, the 6th Cavalry, and Battery F of the 5th Field Artillery.

The Legation Quarter swayed back and forth between violent attacks that drained shrinking stockpiles of ammunition and peaceful interludes during intermittent cease-fires. The Imperial Court declared a cease-fire on July 17, which held for over a week. In a surprising act of consideration, the Imperial Court sent shipments of sweet melons, flour, and ice, a welcome addition to the siege diet of horsemeat, rice, and condensed milk.

Firing again stopped on July 27, giving the legations a bit of a break until August 4. The mysterious maneuverings of the court reflected division among reactionaries who wanted the foreigners killed and reformers and realistic officials who feared devastating retaliation from the West if the foreigners were massacred.

The doubt and division at the highest levels made for a halfhearted effort. Even though

imperial troops fought openly with the Boxers, they never committed the full weight of the army for a final attack. They did not bring forward anything like a substantial portion of the modern European artillery pieces stored in their arsenals. Nigel Oliphant saw a batch of captured guns after the end of the siege. One, a 10-foot-long bronze 30-pounder, bore “a Dutch inscription which shows that it was cast in Rotterdam in 1606.”

News of the departure of a large Allied relief expedition reached Peking, sparking the renewal of hostilities on August 4. After three major battles and much skirmishing, the allies reached Peking from the east on August 13.

Gaselee drew up plans for a united attack, but they fell apart quickly. The Russians moved first, anxious to secure new business concessions and territory. Not only did the Russians move prematurely, they also marched in front of the Americans and attacked the Tung Pien Men, a city gate that had been assigned to the Americans. Not to be outdone by their Russian rivals, the Japanese forces moved in, followed by the other national contingents. The final assault of Peking began.

With the Russians bogged down at the Tung Pien Men, Chaffee turned his attention to a section of the city wall nearby. Two companies of the 14th Infantry reached the foot of the wall. “Heavy rifle fire” rained down from “a pagoda over the gate,” according to Lieutenant Joseph F. Gohn. Officers asked for a volunteer to scale the wall. There were no ropes or ladders available for the attempt, but musician Calvin P. Titus of the 14th Infantry answered, “I’ll try, sir.” Titus climbed up the stone façade at about 10:45 am, getting footholds in cracks and holes in the masonry. More men followed, and they lowered a rope made of rifle slings to pull up their weapons and ammunition. At 11:03 am the regimental flag became the first allied flag to fly atop the wall.

From the Legation Quarter just before 3 pm, a force of what seemed to be German cavalry was sighted nearing the Tartar Wall. When these soldiers grew closer, it turned out that the “Germans” were actually Gaselee and his staff officers accompanied by 60 men from the 7th Rajputs. They entered through the sluice gate of the nearly dry Imperial Canal with the Indian troops tearing at the bars of the gate from the outside as U.S. Marines worked from inside. After 55 days, the siege of the Legation Quarter was over.

Boxer resistance continued in the city, and the little garrison at the Pei Tang Cathedral had to hang on for two more days before it was relieved by Japanese troops.

The Dowager Empress escaped with the court on August 15, before allied forces broke through the gates of the Forbidden City. Mopping-up operations and reprisals continued for weeks in the city and then the region. More allied troops arrived, including an Australian contingent and several thousand Indian troops led by the maharajas of Jodphur, Gwalior, and Bikanir.

Doctor Gustav Velde, surgeon of the German Legation and director of the hospital during the siege, reported that 76 foreigners were killed and 169 were wounded in the siege at Peking. In addition, two Russians died of disease. Twelve of the dead and 23 of the wounded were civilian volunteers. Military casualties included over half the garrison.

Chinese losses were never firmly tallied. Many Chinese deaths were caused by inaccurate artillery and rifle fire in a densely packed urban setting. Stray bullets and shells often overshot the Legation and crashed down into Chinese military positions or civilian homes, shops, and streets some distance away from the fighting.

On September 7, 1900, Chinese officials signed the Boxer Protocol, in which China accepted blame for the Boxer Rebellion and agreed to pay massive damages. Not satisfied with the harsh monetary reparations, Russian forces moved into Manchuria, bringing them on a collision course with the Japanese, who also eyed the region.

In January 1902, the Dowager Empress returned to the Forbidden City. Adjusting to the inevitable, she agreed to some modern reforms. She died in 1908, one day after the young Emperor Guangxu. The ancient empire survived the Dowager Empress by only four years. On February 12, 1912, the Qing Dynasty ended when Emperor Puyi abdicated. China became a republic headed by its first president, Sun Yat-sen.

The ad hoc Eight Nation Alliance had less time left than the crumbling Chinese Empire. Two of its members were soon at each other’s throats in the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War. War broke out in Europe in 1914, eventually pulling in every one of the eight nations. Even Japan entered the war, taking German possessions in the Pacific. The German, Austro-Hungarian, and Russian empires, each of which sent troops into the Dowager Empress’s Forbidden City, collapsed in 1918. The imperial thrones of Berlin, Vienna, and St. Petersburg, which looked so invincible in 1900, lasted scarcely half a dozen years longer than the doomed court of the Forbidden City.

![An American, Mrs. W.S. Woodward, wrote that “a large Russian” [evidently a marine] interrupted the burial, saying in broken English, “He no comfortable.” The Russian stepped into the grave, patted and raised the earth under Tutcher’s head, and rearranged his arms and hands. “We brothers. We fought in the war together,” he said.](https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/Under-8-Flags-The-Boxer-Rebellions-Unlikely-Alliance-7.jpg)

Loved this article on a little-known piece of history. Thank You for it.