By Maj. Gen. Michael Reynolds

Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily, was the only operation in World War II in which generals Bernard Montgomery and George S. Patton, Jr., participated as equals. Monty was commanding the British Eighth Army and Patton the American Seventh. It is also noteworthy that the initial assault force, more than eight divisions, was in fact larger than that used in the invasion of Normandy, making Husky numerically, in terms of men landed on the beaches and frontage, the largest amphibious operation of World War II.

The basic plan included Monty’s Eastern Task Force of some 115,000 men with four infantry divisions, including one Canadian division; an independent infantry brigade; and a Canadian armored brigade. The main effort landed on a 40-mile front in southeast Sicily from the Pachino Peninsula to Syracuse. Patton’s Western Task Force of some 66,000 men with one armored and three infantry divisions was to land in the Gulf of Gela between Licata and Scoglitti and then move rapidly inland to seize the airfields just north of Gela.

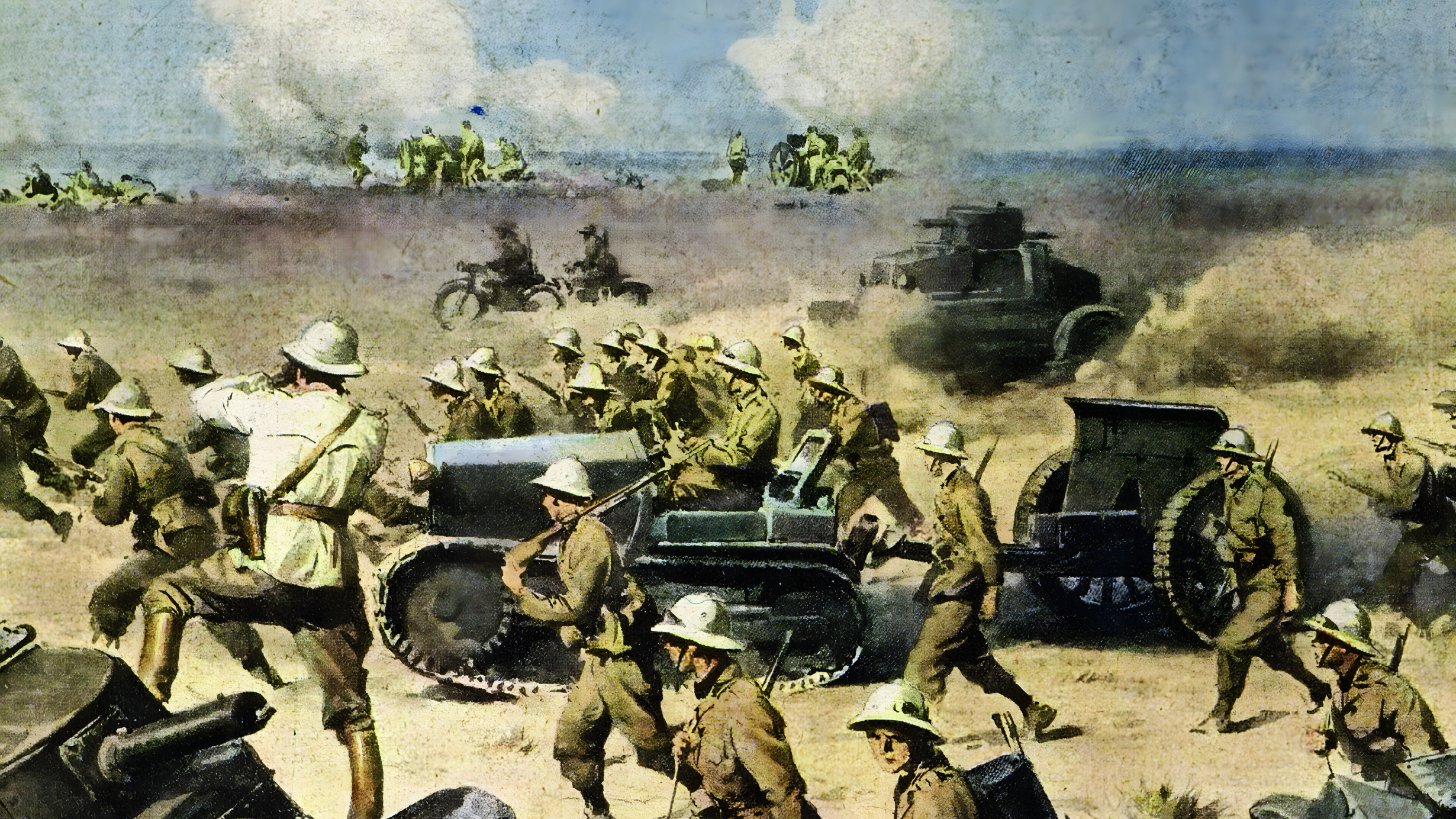

Monty and Patton had never met to discuss the overall plan, but they were both clear that the Seventh Army’s mission was to protect the Eighth Army’s left flank as it made the main thrust toward Messina. The opposition facing the Allies totaled 10 Italian infantry divisions, of which six were immobile coastal formations, the Hermann Göering Panzer Division, and two similarly reformed panzergrenadier divisions. Plentiful reinforcements were available from mainland Italy. It is also important to understand the topography of the island. “Sicily is very mountainous and [vehicle] movement off the roads and tracks is seldom possible,” described Montgomery. “In the beach areas there was a narrow coastal plain, but behind this the mountains rose steeply … It was apparent that the campaign in Sicily was going to depend largely on the domination of main road and track centres.”

To fully understand the difficulties facing the British, American, and Canadian troops, one has to go to Sicily and see the ground. Only then can one fully understand the extent to which Mount Etna dominates the northeast third of the island; and even then one has to remember that none of today’s highways with their wide surfaces, tunnels, and super viaducts existed in 1944. Of the four narrow roads that led north from the landing beaches, only two went all the way to Messina—one running along the eastern coast from Catania and the other turning east after reaching the northern coast. Monty planned from the outset to make his main thrust up the east coast, and it did not take long for Patton to realize that if he was to reach Messina before Monty he had no choice other than to strike north and then east along the northern coast road, Highway 113.

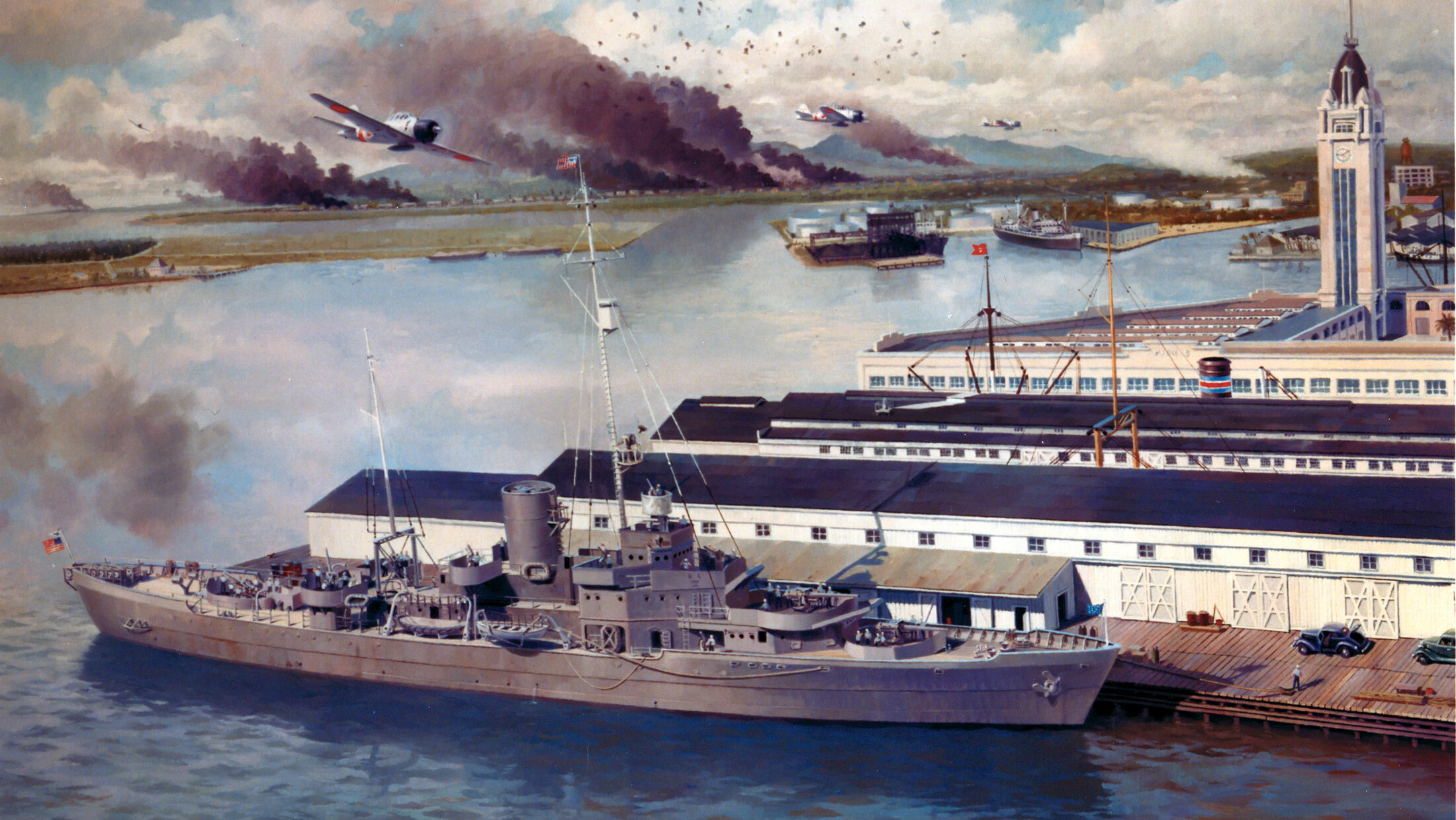

The 2,760 ships and landing craft carrying the two task forces came from as far afield as Scotland, the United States, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, and Lebanon. They rendezvoused off Malta, where General Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander of Allied forces in North Africa, Monty, and the commander of Allied Naval Forces in the Mediterranean, British Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, had located themselves. With the help of bad weather, which led the defenders to believe no landings were possible, the American and British troops stormed ashore against virtually no opposition some two hours before dawn on July 10, 1943.

Inevitably, many things failed to go exactly according to plan, particularly the airborne operations that had preceded the landings. The U.S. 82nd and British 1st Airborne divisions suffered very heavy losses due to badly trained pilots, high winds, and heavy antiaircraft fire, both enemy and friendly. Nearly 400 aircraft and 137 gliders were involved. Thirty-six of the gliders landed in the sea, drowning 252 men of the British 1st Air Landing Brigade, and only 12 gliders reached their objectives. Some 3,400 U.S. paratroopers, who should have been dropped northeast of Gela, landed over a 1,000-square mile area of southeastern Sicily. Their commander, Brigadier General Jim Gavin, came down over 25 miles from his intended landing site. Nevertheless, Monty’s insistence on an overwhelming concentration of ground forces ensured overall success.

Monty was so elated with the success of the landings that at 1030 hours on the 10th he went in person to see Admiral Cunningham to express his “great appreciation of the work of the Navy,” and he followed this up with a letter to British Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder, commander of the Allied Air Forces in the Mediterranean, congratulating him on the fact that “the Allied Air Forces had definitely won the air battle.” These were generous gestures since both men detested Monty and had vigorously opposed his plan for the invasion, Tedder on the grounds that air cover could not be guaranteed before the capture of the Gela and Comiso airfields, and Cunningham saying that he would not commit the navy without guaranteed air cover. Both had finally given way.

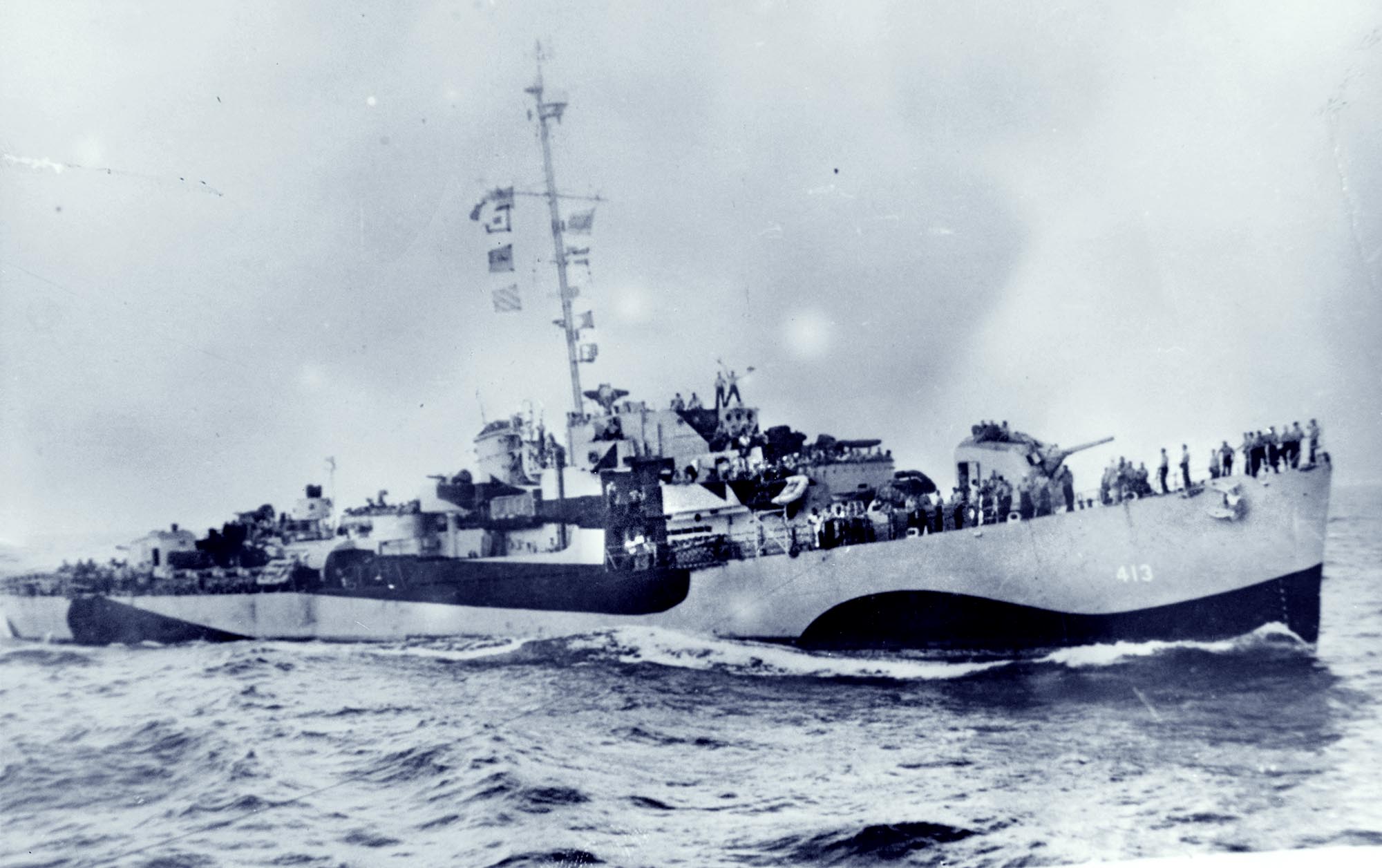

Monty’s enthusiasm was translated into firm directives that evening when he signaled both his corps commanders, General Oliver Leese of XXX Corps and General Miles Dempsey of XIII Corps, to “operate with great energy” toward Noto and Avola in the first case and Syracuse in the second. He then embarked in the destroyer HMS Antwerp and landed on the Pachino Peninsula at 0700 hours the following day. His morale received another boost when he learned that the whole peninsula was secure and that the port of Syracuse had been captured intact.

With an arrogance that would have caused problems with anyone other than British General Sir Harold Alexander, his boss and the commander of the 18th Allied Army Group, Montgomery signaled, “Everything going well here … No need for you to come here unless you wish. Am very busy myself and am developing operations intensively … Have no, repeat no, news of American progress … if they can … hold firm against enemy action from the west I could then swing hard with my right with an easier mind. If they draw enemy attacks on them my swing north will cut off enemy completely.”

Patton Gets into the Mix

It was clear that Monty was telling his commander how subsequent operations should be developed, and this did not bode well for future relations between himself and George Patton.

Patton had embarked in the American naval task force commander’s flagship Monrovia four days before the landings. He wrote in his diary on July 9: “I have the usual shortness of breath I always have before a polo game. I would not change places with anyone I know right now.”

Following the successful American landings, Gela was captured by midday. Patton remained aboard the Monrovia throughout July 10, but when the enemy launched a major counterattack in the Gela sector on the morning of the 11th he could restrain himself no longer and at 0930 hours he disembarked, wading ashore as one eyewitness recalled “resplendent in an immaculate uniform complete with necktie neatly tucked into his pressed gabardine shirt, knee-length polished black leather boots and his ever-present ivory-handled pistols strapped to his waist.”

Patton arrived at the Ranger headquarters in Gela just in time to witness a second enemy counterattack being beaten off. He then went on to see the commander of the 1st Infantry Division, Maj. Gen. Terry Allen. Needless to say he could not resist interfering and issued orders that the Division was to push inland, ignoring a strong German pocket of resistance to its rear. This was in direct contradiction of the corps commander’s orders. The latter, Maj. Gen. Omar Bradley, wrote later, “He countermanded my Corps order to the Div without consulting me in any way. When I spoke to him about it George apologized and said he should not have done that. But George didn’t like it.”

Thanks to a British newspaper correspondent who never even went ashore in the first two days of the invasion, the New York Herald Tribune Los Angeles Evening Herald-Express carried wildly exaggerated reports of Patton’s first actions in Sicily. “Patton leaped ashore to head troops at Gela,” trumpeted the former, while the latter ran the headline: “Patton led Yanks against Nazi tanks in Sicily.” Its subsequent story read that Patton had “leaped into the surf from a landing boat and personally taking command, turned the tide in the fiercest fighting of the invasion of Gela.” Nothing could have been further from the truth. The Rangers, the men of the 1st Infantry Division, and the tanks of the 2nd Armored Division beat off the counterattacks without any help from Patton. At 1900 hours he was back on the Monrovia. That evening he noted in his diary: “This is the first day in this campaign that I think I earned my pay.”

Monty Bypasses the Chain of Command

Patton was not alone in bypassing the normal chain of command and giving orders directly to divisional commanders. Monty went even further. The commander of the 50th Infantry Division recalled that on July 12, he “… got a message, return at once to your Headquarters, Army commander wants to see you … Monty explained to me that he was going to drop parachutists … and that I’d got to get forward as fast as possible to relieve them … Monty gave these instructions to me, not Dempsey [his corps commander] … ” Usually in an army, the army commander would give orders to the corps commander who would summon the divisional commander. Monty was determined to impress his personality on the chap who was doing the job.

The commander of the 51st Highland Division later remembered that during the same day Monty had gone even further and given orders directly to one of his “brigade commanders.

July 12 was a pivotal day in the relationship between Monty and Patton. At 2200 hours, the Eighth Army commander signaled Alexander. “My battle situation very good … Intend now to operate on two axes. XIII Corps on Catania and northwards. XXX Corps on Caltagirone–Enna–Leonforte. Suggest American Div at Comiso might now move westwards to Niscemi and Gela. The maintenance and transport and road situation will not allow two Armies both carrying out extensive offensive operations. Suggest my Army operates offensively northwards to cut the island in two and that the American Army holds defensively … facing west.”

It is quite clear from the above that Monty, having received no directions of any sort from Alexander as to how future operations should be developed, had decided to take matters into his own hands and do the commander’s job for him. In doing so, he uncharacteristically split his army and departed from his normal principle of concentration of force.

A look at the map shows that in fact Monty’s proposals made sound military sense—as well as thrusting directly toward Messina, he would, by cutting inland toward Enna, be outflanking the Axis forces facing the Americans north of the Gulf of Gela. Alexander, however, did nothing, and the U.S. 45th Infantry Division continued moving up the Vizzini–Enna road (Highway 124). Monty wrote later in his diary, “The battle in Sicily required to be gripped firmly from above. I was fighting my own battle and the Seventh American Army was fighting its battle; there was no co-ordination by 15th Army Group [Alexander].”

Inter-Army Boundary Change Peeves Bradley

Frustrated by the lack of response from his commander, Monty again took matters into his own hands and ordered the 51st Highland Division, 23rd Armored Brigade, and the 1st Canadian Infantry Division to move up Highway 124—right across the path of the advancing 45th U.S. Division!

On July 14, Alexander finally responded to Monty’s request and moved the inter-Army boundary, a boundary that had been agreed long before the landings. This resulted in the 45th Division being completely wasted; it was forced to pull back all the way to Gela and then move west to the left flank of the 1st Division.

Omar Bradley, commanding II U.S. Corps, was understandably furious. He recalled later, “We had a boundary for II Corps which went through Ragusa to the north to Vizzini … Just before we got there, we got [an] order changing the boundary—switching us off to the north-west and giving that road as boundary to the British including the road … I was peeved … They [the new orders] were so obviously wrong and impractical. We should have been able to use that road, even if we would have shifted to the left—used it to move to the left.”

Monty’s attempt to drive northwest and outflank the enemy in front of the Americans came to nothing. By the time the British, lacking mobility, reached Highway 124 and the sector south of Vizzini, the Germans had brought in armor and were able to hold on. Leese, the British XXX Corps commander, said later that he thought the decision to move the boundary and pull the 45th Division back was a mistake. “I often think now that it was an unfortunate decision not to hand it [the Caltagirone–Enna road] to the Americans … They were making much quicker progress than ourselves, largely owing, I believe, to the fact that their vehicles all had four-wheel drive … We were still inclined to remember the slow American progress in the early stages in Tunisia, and I for one certainly did not realise the immense development in experience and technique which they had made. . . I have a feeling that if they could … [have been allowed to drive] straight up this road [Highway 124], we might have had a chance to end this frustrating campaign sooner.”

Monty’s thrust toward Catania was also frustrated when the Germans suddenly and dramatically reinforced their defenses with a strong parachute force.

Patton is Slammed by Eisenhower; Blindsided by Alexander

But what was the reaction of the commander of the Seventh U.S. Army to these dramatic events? On July 12, Eisenhower had visited Patton, who was still aboard the Monrovia. Ike was in a bad mood and had already sent a signal blaming Patton’s command for a tragedy the previous evening when Allied naval forces had shot to pieces an aerial convoy bringing in a regimental combat team of the 82nd Airborne Division. Sixty pilots and 81 paratroopers had died. Ike demanded an investigation and ordered that action be taken against those responsible. Not content with that, he proceeded to castigate Patton for the inadequacy of his progress reports and, as if that was not bad enough, he left without saying anything positive about the successful landings in the Gulf of Gela. The following day Patton wrote in his diary: “Perhaps Ike is looking for an excuse to relieve me … If they want a goat, I am it.”

There is no doubt that the confrontation with Ike affected Patton deeply, and it may well have made him reluctant to challenge Alexander’s decision to change the inter-Army boundary. Maybe he would have done so if Alexander had come clean with him during a visit on the 13th. By then, the latter knew of Monty’s suggestion that the boundary should be changed, but he made no mention of it and, unforgivably, Patton was left in the dark for several more hours. He did, however, obtain the commander’s agreement to expand his operations to the northwest and take Agrigento, but only provided he continue to protect the Eighth Army’s left flank and did not get involved in a major engagement. Patton and the commander of the 3rd Division, General Lucian Truscott, agreed that a “reconnaissance in force” would meet Alexander’s requirement.

When Patton learned of the inter-Army boundary change on July 14, he determined that it was time to stop playing second fiddle to the British. This resolution was strengthened even further when on July 16, he received a message from 15th Army Group instructing him to occupy a defensive line running northward from Caltanissetta with the aim of protecting Monty’s XXX Corps as it swung east toward Leonforte. Patton knew that the Eighth Army’s several thrusts were in trouble after encountering strong German resistance, and with only relatively weak Italian forces on his own front he saw his chance.

Patton Heads for Palermo

“Monty is trying to steal the show and with the assistance of Divine Destiny [Eisenhower] he may do so,” Patton wrote in his diary that evening. The following day he arrived without warning at Alexander’s headquarters in Tunisia and suggested that his army should advance on two fronts with Bradley’s II Corps driving north to Termini, while a provisional corps made up of the 2nd Armored, 3rd Infantry and 82nd Airborne divisions under his deputy, Major General Geoffrey Keyes, cleared the western part of the island.

In fact, Patton’s eyes were not set on Termini, but rather on the capital of Sicily—Palermo. Alexander was clearly caught off guard. Instead of taking control of his two strong-willed subordinates and ordering Monty to concentrate on holding the Germans in place and Patton to forget western Sicily and drive north and then east to Messina to cut off the Axis forces in the northeast of the island, he agreed and the campaign dragged on for another month.

Although Brig. Gen. Maxwell Taylor, the artillery commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, described the provisional corps’ advance into northwestern Sicily as “a pleasure march, shaking hands with Italians asking, ‘How’s my brother Joe in Brooklyn?’ Nicest war I’ve ever been in!” it was in fact extremely unpleasant for many of the GIs who had to march over 100 miles through very rugged country in stifling heat and swirling dust. Nevertheless, Palermo fell to Truscott’s 3rd Infantry Division on July 21, and his men were greeted by thousands of flag-waving Sicilians.

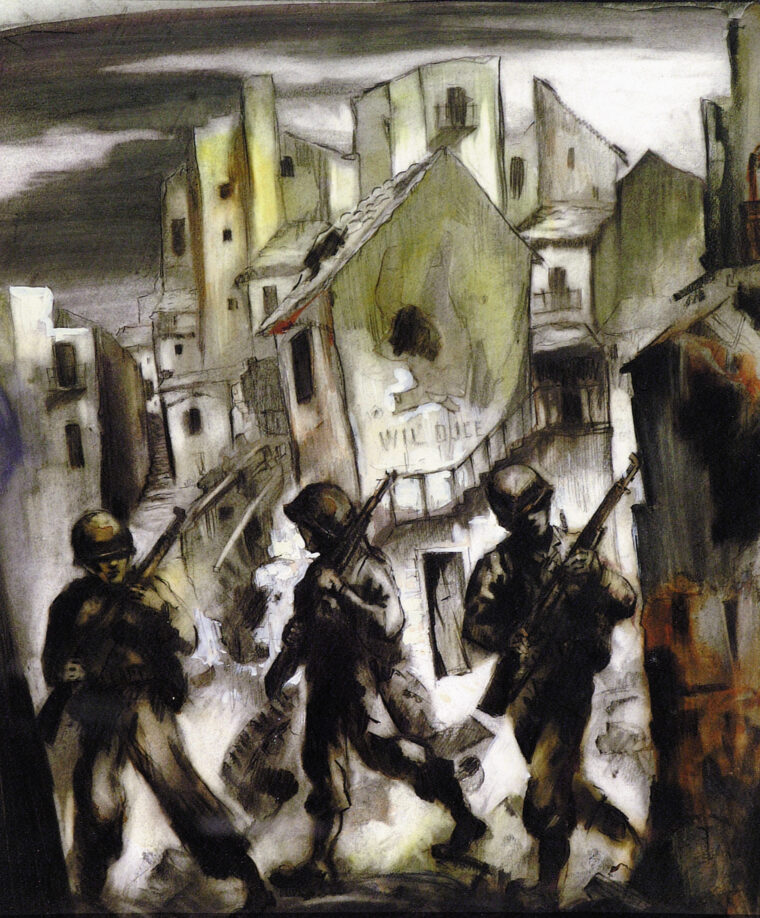

When Patton himself arrived in Palermo after modestly allowing Keyes, the provisional corps commander, to enter first, he was greeted with cheers of “Long Live America!” and “Down with Mussolini!” He quickly established his headquarters in the royal palace and “had it cleaned by prisoners for the first time since the Greek occupation [241 BC].” It was there that he was visited by the cardinal of Palermo’s representative, ate “K-rations on china marked with the cross of Saxony” and “got quite a kick about using a toilet previously made melodious by constipated royalty.”

On July 23, Bradley’s II Corps reached the northern coast at Termini and Patton lost no time in ordering it to turn east. He was determined to beat Monty to Messina.

Monty’s Momentum is Stalled

What did Monty make of the Seventh Army’s advances to Palermo and Termini? By the time Bradley’s II Corps reached the latter on July 23, Monty realized that his own dispersed thrusts, aimed at bypassing Mount Etna via Adrano on the west side and Fiumefreddo on the eastern coast road, were getting nowhere. The ground was the most difficult in the whole of Sicily, and the Germans were inevitably making good use of it. After the war he blamed a lack of coordination of the land, sea and air efforts for the delay in gaining “control of the island more quickly, and with fewer casualties … the Supreme Commander was in Algiers, Alexander … was in Sicily; Cunningham, the Naval C-in-C, was in Malta; whereas Tedder, the Air C-in-C had his Headquarters in Tunis. When things went wrong, all they could do was to send telegrams to each other.”

In fact, there were two basic reasons for this delay—one, Alexander’s failure to coordinate the Seventh and Eighth armies; and two, Monty’s failure to understand early enough the topographical difficulties involved in trying to advance past the east and west sides of Mount Etna. On July 19, Monty had signaled Alexander, outlining his axes of advance around either side of Mount Etna and suggesting that “when the Americans have cut the coast road north of Petralia, one American division should develop a strong thrust eastwards towards Messina so as to stretch the enemy who are all Germans and possibly repeat the Bizerta manoeuvre [i.e., cut them off].”

This made complete military sense, but by the 17th Patton had persuaded Alexander to allow him to drive toward the northwestern part of the island. When Alexander tried to restrain Patton by sending him a new directive on the evening of the 19th, it was too late. The directive, in accordance with Monty’s suggestion, ordered Patton to first cut the coastal road north of Petralia and only then to move on Palermo. However, the Seventh Army Chief of Staff, Brig. Gen. Hobart Gay, kept the first part of the message from Patton, ensured that the remainder took a long time to be decoded, and then asked for it to be repeated on the grounds that it had been garbled! By the time this problem had been resolved, the advance guard of Keyes’ provisional corps was already in Palermo and Monty’s idea of an American division helping him, at least in the short term, had been frustrated.

By July 23, Monty realized he had been overambitious and that the cost of trying to break through the German defenses astride Mount Etna, known as the Etna Line, was going to be too great. Two days earlier, he had closed down the XIII Corps drive up the east coast, and he now sent a message to Patton inviting him to come and discuss the capture of Messina. He offered, “Many congratulations to you and your gallant soldiers on securing Palermo and clearing up the western half of Sicily.” Privately, of course, he believed Patton’s Palermo escapade had been a completely wasted effort.

Why Did Monty Offer Patton the Prize of Taking Messina?

Patton met Monty at Syracuse airfield on the 25th. Expecting the worst and mistrusting his comrade’s intentions, he was astounded when Monty suggested that the Seventh Army should use both the major roads north of Mount Etna (Highways 113 and 120) in a drive to capture Messina. In fact, Monty went even further and suggested that his right hand, or southern, thrust might even cross the inter-Army boundary and strike for Taormina, thereby cutting off the two German divisions facing the Eighth Army; the latter would “take a back seat.”

That same evening, Patton wrote in his diary: “I felt something was wrong, but have not found it yet. After all this had been settled, Alex [Alexander] came. He looked a little mad and, for him, was quite brusque. He told Monty to explain his plan. Monty said he and I had already decided what we were going to do, so Alex got madder and told Monty to show him the plan. He did and then Alex asked for mine. The meeting then broke up. No one was offered any lunch and I thought that Monty was ill bred both to Alexander and me. Monty gave me a 5-cent lighter. Someone must have sent him a box of them.”

Monty described the ‘plan’ in his own diary: “… the Seventh American Army should develop two strong thrusts with (a) two divisions on [Highway 120] (b) two divisions on [Highway 113] towards Messina. This was all agreed.”

What is the explanation for Monty’s surprising generosity in offering the prize of Messina to Patton? A major factor was certainly his wish to avoid further British and Canadian casualties in an attempt to breach the Etna Line. By July 27, the Eighth Army had suffered some 5,800 casualties. Another was his wish that his army, not Patton’s, should mount the main invasion of the Italian mainland. As early as the 23rd he had signaled Alexander, “Consider that the whole operation of war on to mainland must now be handled by Eighth Army as once Sicily is cleared of enemy a great deal of my resources can be put on to the mainland. I will carry the war into Italy on a front of two Corps.”

By giving Patton the main role in finishing off the enemy in Sicily, Monty planned to rest the two corps just mentioned in preparation for the forthcoming invasion. They would then assault the toe of Italy in conjunction with a landing in the Gulf of Gioja by the X British Corps sailing directly from North Africa.

Patton and Monty Meet in Palermo

On July 28, Monty flew to Palermo in his Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress for further discussions with Patton. Unfortunately, the landing strip was too short. Montgomery remembered, “The pilot did the most amazing job … He put all the brakes on one side and revved one engine and swung the whole thing round—which wrote it off. That was the end of it.”

Monty emerged from the wreck seemingly unperturbed, to be met, not by Patton but, by an aide. It was Patton’s way of getting back at him for his rudeness in Syracuse. Nevertheless, he then put on a typical Patton reception with motorcycles and scout cars to escort Monty to the palace in Palermo where a band and guard of honour were waiting to greet him. After a formal lunch, the two men reviewed their future plans and Monty again emphasized the importance of the Seventh Army’s thrust to Messina.

He wrote in his diary, “We had a great reception. The Americans are very easy to work with. I discussed plans for future operations with General Patton. Their troops are quite first class and I have a very great admiration for the way they fight.”

Patton was still very wary of Monty’s intentions and sent a note to the commander of the 45th Division. “This is a horse race in which the prestige of the U.S. Army is at stake. We must take Messina before the British. Please use your best efforts to facilitate the success of our race.”

Patton’s Questionable Behavior

George Patton’s behavior during the last three weeks of the campaign in Sicily can only be described as extraordinary. He castigated Omar Bradley for the tactics being employed by his II Corps, telling him, “I want you to get into Messina just as fast as you can. I don’t want you to waste time on these maneuvres [outflanking enemy resistance], even if you’ve got to spend men to do it. I want you to beat Monty into Messina.”

On another occasion he allegedly accused the commander of the 3rd Infantry Division, Truscott, of being “afraid to fight.” Bradley stated later, “Patton was developing as an unpopular guy. He steamed about with great convoys of cars and great squads of cameramen … To George, tactics was simply a process of bulling ahead. Never seemed to think out a campaign. Seldom made a careful estimate of the situation. I thought him a shallow commander … I disliked the way he worked, upset tactical plans, interfered in my orders. His stubbornness on amphibious operations, parade plans into Messina sickened me and soured me on Patton. We learned how not to behave from Patton’s Seventh Army.”

The reference to amphibious operations was in relation to three landings made on the north coast of Sicily during the advance to Messina, known to the Americans as end runs. Patton did not in fact interfere in the first successful landing, but he ordered the second to take place earlier than Bradley and Truscott wished, ending in a minor disaster, and he ordered the third to take place despite the fact that the 3rd Division had already advanced beyond the landing site!

Patton Wins the Race to Messina

Patton’s “parade plans into Messina” again reflected badly on him as an army commander. Although a patrol of the 3rd Infantry Division had entered the city on the evening of August 16, Patton gave orders that no formed units were to enter until he personally could make triumphal entry. Bradley recalled that he “had to hold our troops in the hills instead of pursuing the fleeing Germans in an effort to get as many as we could. [The] British nearly beat him into Messina because of that.”

At 1000 hours on August 17, Patton led an American column into Messina. Ike’s liaison officer with Patton, Maj. Gen. John Porter Lucas, who was in the following vehicle, recorded in his diary: “We entered the town about ten-thirty amid the wild applause of the people … The city was completely and terribly demolished.”

German long-range artillery fire landed near the third vehicle, wounding its occupants, but this did not deter Patton, who proceeded on to the central piazza where he met British troops who had carried out an amphibious landing south of the city near Scaletta on the 15th. The commander of the British force, Brigadier J. C. Currie, saluted Patton “dazzling in his smart gabardines,” and is reported to have said, “General, it was a jolly good race. I congratulate you.” The film Patton gives a completely false version of this event. Monty himself is depicted leading a British column into Messina, only to be greeted by Patton with a smirk on his face, having beaten his arch-rival into the city.

Although Husky was successful, there is no doubt that bungling and lack of direction and coordination by both Eisenhower’s and Alexander’s headquarters allowed 40,000 Germans, 60,000 Italians and some 10,000 vehicles, including 47 tanks, to escape in a skilfully executed withdrawal across the Straits of Messina. Admittedly, the Axis forces had suffered 160,000 casualties, of which 140,000 were prisoners, but the cost to the Allies had been heavy—12,843 British Commonwealth casualties and 8,781 Americans. These figures can be doubled if one takes into account those who were evacuated with malaria. Monty blamed higher command for the failure to stop or at least heavily interfere with the Axis withdrawal.

As early as August 7, having seen the latest Royal Air Force reconnaissance reports and aware that the Etna Line had finally been broken by his XXX Corps, he noted, “There has been heavy traffic all day across the Straits of Messina and the enemy is without doubt starting to get his stuff away. I have tried hard to find out what the combined Navy-Air plan is in order to stop him getting away; I have been unable to find out. I fear the truth is that there is NO plan … The trouble is there is no high-up grip on this campaign … It beats me how anyone thinks you can run a campaign … with the three Commanders of the three Services about 600 miles from each other.”

Surprisingly, Monty did not include Ike in his criticism. It was after all the latter’s responsibility to coordinate the activities of his service commanders. Eisenhower finally did so on August 9, but even after that there was still no coherent interdiction plan and Monty could do nothing other than to watch the enemy escape and his rival claim the limelight.

Maj. Gen. Michael Reynolds was a graduate of the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst. He served in the British Army around the world and was seriously wounded during the Korean War. He was the former director of NATO’s Military Plans and Policy Division and the author of four well-received books.

Join The Conversation

Comments