by Vince Hawkins

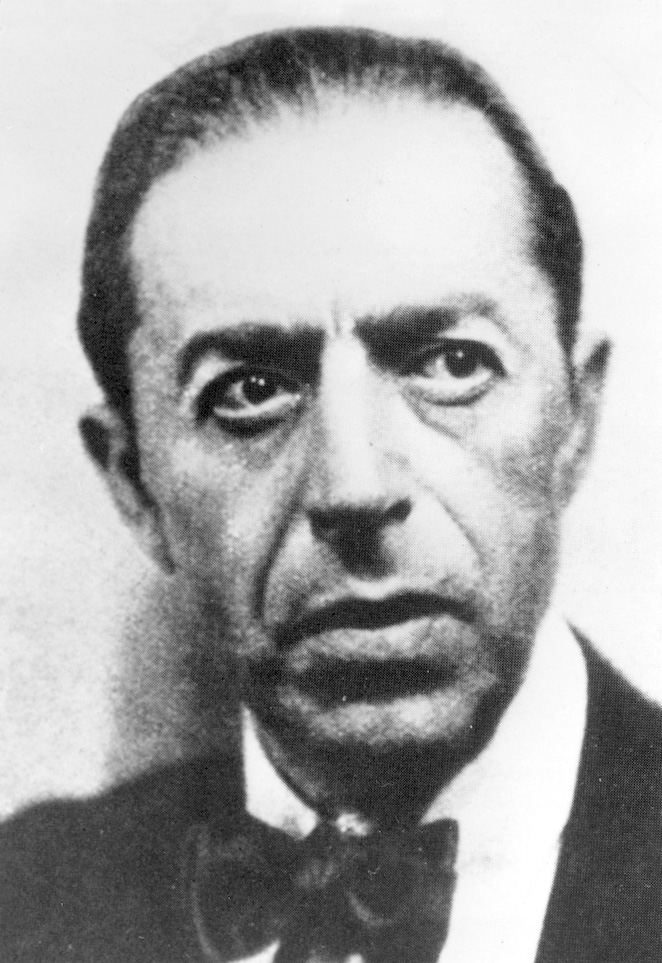

On the evening of November 5, 1925, Prisoner #73 was taken from his cell in the infamous Lubyanka Prison and driven to a woods in the Sokolniki district outside Moscow. In the car with the prisoner were three members of OGPU, the Soviet military intelligence service, who served as his escort. The car stopped along the Bogorodsk Road, just beyond a small pond, and the prisoner was let out of the car and allowed to take a walk in the woods. This was not an unusual occurrence, as Prisoner #73 had been on such walks many times before. This form of exercise was often granted to him after a long interrogation session by the OGPU and usually took place every few days. Tonight, however, was to be different. The prisoner, having just begun his stroll, was roughly 30 to 40 paces from the car when the driver, OGPU officer Ibrahim Abisalov, drew his pistol and shot him in the back. Prisoner #73 never saw it coming, nor could he have escaped it had he known. Despite any personal feelings the OGPU officers may have had concerning the prisoner, the orders for the execution were not to be questioned, for they came directly from Stalin himself. The end result was that Sidney Reilly, the man once known as the British Secret Intelligence Service’s “ace of spies,” was dead.

Or was he? There have been numerous reported “sightings” of Sidney Reilly alive throughout the 1920s and 1930s, during World War II, and even as late as 1960! Even the sequence of events concerning his murder contains some elements of inconsistency. One version of the story claims Reilly was shot once in the back, and when found to be still alive, his body was rolled over and he was shot again in the chest. Another claims he was shot once in the back by Abisalov, while yet a third states he was shot several times in the back by both Abisalov and Grigory Syroezhkin, another of the OGPU officers who were with him in the car. Even the spelling of Abisalov’s name, by the same person recounting the events, is different. In one version, it is spelled “Abissalov,” using a double “s.”

A Man of Mystery and Intrigue

While these inconsistencies are relatively minor points, they do make for a very interesting end for the man whose passion for intrigue, obfuscation, double-dealing, and outright lying about his past made him famous during his life. One cannot help but think that the lack of irrefutable evidence surrounding even the events of his death would probably bring a smile to the face of Sidney Reilly.

The exact date of his birth and even his true name are in question. Most fairly reliable sources give his birth date as March 24, 1874, and the location as in or somewhere near Odessa, in the Ukraine. Other sources state he was born in 1873. His name has alternately been given as Georgi Rosenblum, Sigmund Rosenblum, Shlomo Rosenblum, Salomon Rosenblum, and even Sigmund Georgjevich Rosenblum. Supposedly, Reilly himself claimed that Rosenblum wasn’t his real name, but that when his father—a Russian Army colonel with connections at the Czar’s court—died, he learned the dreaded family secret that he was the progeny of an affair between his mother and her Jewish doctor, named Rosenblum. Little wonder that with such auspicious beginnings his entire life would be one of uncertainty and confusion concerning his true past.

As a young university student, Reilly purportedly became involved with an early Marxist group called The Friends of Enlightenment and acted as a courier for them. He was arrested by Czarist police and thrown into jail. When he was released, he learned of his mother’s death and the secret about his real father. Apparently embarrassed by his Jewish parentage—like most Russians at this time, he was virulently anti-Semitic—and upset by both his mother’s death and her betrayal, Reilly fled from his family and stowed away on a British ship bound for South America. (There is also the story that he feigned his own death by drowning to make a complete break from his family.) Under the name of Pedro, he pretended to be South American and got a job as a cook for a British mission in Brazil.

During an attack by a local tribe, Pedro is said to have saved the lives of the mission group. One of them, a British agent named Major Fothergill, gave Pedro £1500 out of gratitude. When Fothergill learned who Pedro really was, he arranged both a passport and passage for him to England. A different account of Reilly’s arrival in England says that his knowledge of languages—he was apparently fluent in seven—impressed some British Army intelligence officers visiting Brazil, and they arranged for him to go to England where he was later recruited as a spy for the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS). Yet a third story has Reilly in Paris, working for the Okhrana, the Imperial Russian Secret Police, spying on Russian radicals. In 1895, Reilly and his case officer appear to have murdered two couriers carrying money for a Russian revolutionary group, and with his share of the money, Reilly went to England.

”Miracle Cures” and Murder

However he got there, Reilly did arrive in England in 1895 and set himself up in London. By 1896, he had started a business as a consulting chemist under the name of Rosenblum & Company. Within nine months he was a fellow of the Chemistry Society and a member of the Institute of Chemistry. It seems that, instead of actually being a chemist, he was manufacturing and distributing patent medicines or “miracle cures” to an unsuspecting public. It was around 1898 that he married his first wife, a widow named Margaret Thomas, who had inherited a small fortune from her late husband, Hugh Thomas. It has been suggested that Reilly and Margaret were involved in an affair, and that Reilly, or both of them, murdered Margaret’s husband so they could marry and inherit Hugh’s money. It is even suggested that Reilly impersonated the local doctor and signed the death certificate, thereby removing suspicion from himself.

Following the marriage, Sigmund Rosenblum changed his name, taking the Irish surname Reilly, which was Margaret’s maiden name, and became Sidney Reilly, also known as Sidney George Reilly. There are several plausible reasons for the name change, but the most revealing is what Reilly himself said, “In Europe, only the British hate the Irish, but everyone hates the Jews.”

Margaret was the first of an unverifiable number of wives and mistresses credited to Reilly. Estimates of Reilly having three or four wives and at least six mistresses are about the average. At least two of Reilly’s marriages were witnessed by members of the SIS, who knew them to be bigamous but said nothing because Reilly was working for them. One of his reputed mistresses was Ethan Lilian Voynich, author of The Gadfly, a novel published in 1897. According to the book Reilly, Ace of Spies by Robin Bruce Lockhart, the son of a British agent named Robert Bruce Lockhart who worked with Reilly, “He [Reilly] was not angry when she later published a novel, much praised by the critics, which was largely inspired by his early life.”

“Trust No One.”

Considering the times and the nature of his work, it is not all that surprising that Reilly would have had several wives and mistresses. Nor is it unbelievable that Reilly would have had such an effect on women that he could have so many wives and mistresses. By the accounts of those who knew him well, Reilly’s character left an indelible impression. He was suave, debonair, self-confident, and able to “charm the pants” off both women and men alike. He was overtly generous with his friends and those rare family members with whom he associated. He enjoyed gambling with both his money and his life and often gave his friends bags of gold sovereigns with which to gamble against him. He could also be cold and pragmatic, capable of using any and every means to get what he wanted. On his personal stationary was the motto Mundo Nulla Fides, translated as “Put no faith in the world,” or more simply, “Trust no one.”

Richard B. Spence, the author of Trust No One—The Secret World of Sidney Reilly, described Reilly as “a mercenary of a rather specialized sort … a freelance entrepreneur in the business of information and influence.” Commenting on his character, Reilly described himself as “a practical man.”

The patent medicine business not bringing in the kind of money he wanted, Reilly began to work as an informer for Scotland Yard’s Special Branch, supplementing his income by spying on radicals and revolutionaries among the Russian émigré community. When his name was linked to an Okhrana investigation of a London-based counterfeiting ring producing fake Russian rubles, the head of Special Branch decided Reilly should leave immediately. With a new passport, Reilly and his wife hurriedly left London in June 1899 and headed for the one place no one would think to look for them—Russia.

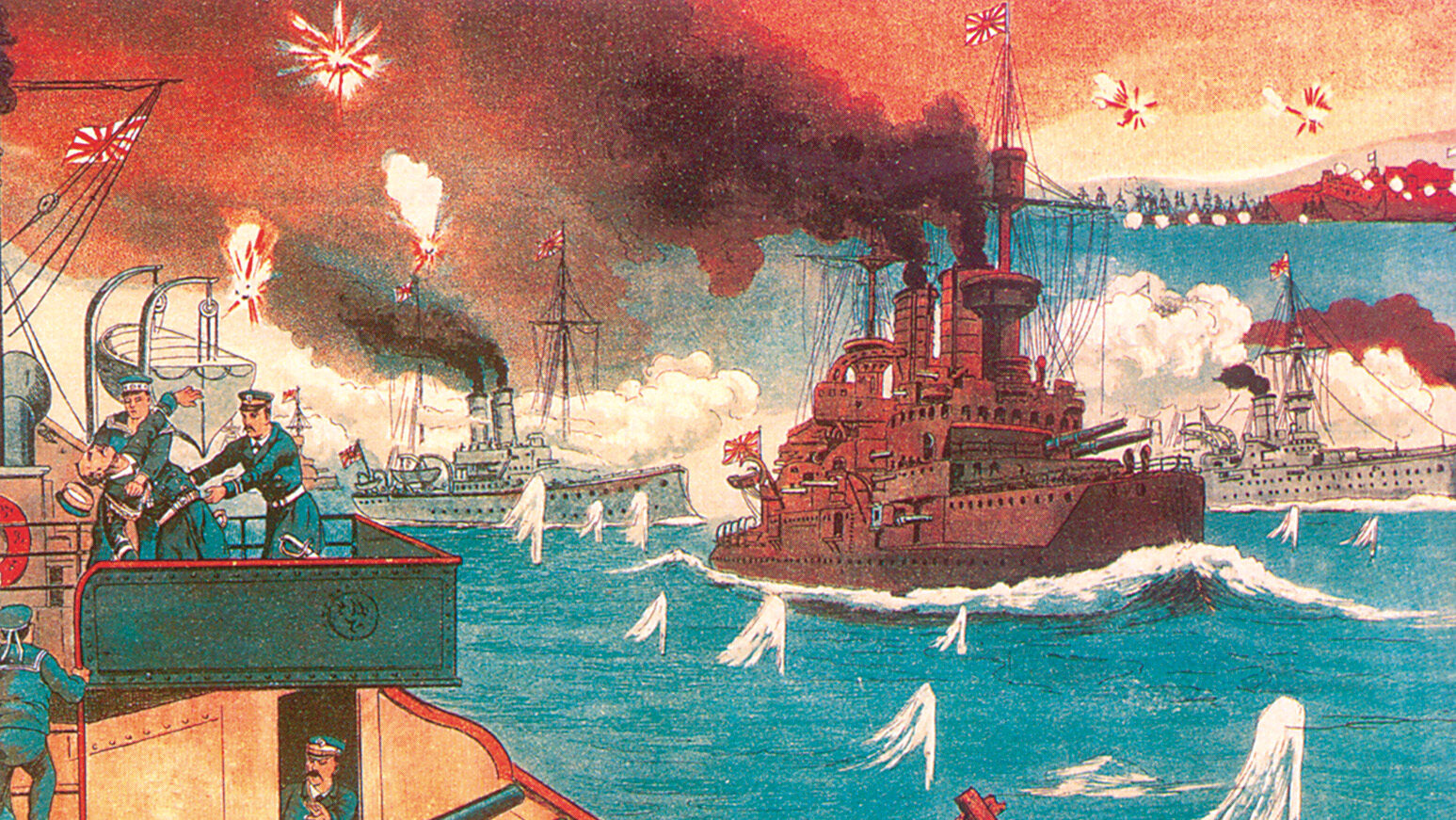

The timeline of his life and activities becomes rather fragmented over the next several years, but existing records seem to indicate that Reilly was working for British intelligence during this period. During the Boer War, he is reported to have been in Holland where, portraying a Russian arms merchant, he reported to London on Dutch armaments shipments to South Africa. Reilly then traveled to Port Arthur in Manchuria, disguised as a timber salesman, to spy on the Russian’s new naval base. He apparently sold information regarding the base to the Japanese as well as passing it on to British intelligence. The whole time, he continued to work his own schemes and businesses—to his profit and his unfortunate client’s regret.

It was his involvement in the d’Arcy affair that earned Reilly his greatest notoriety to date and the thanks of a grateful British government. At the instigation of the First Sea Lord, Reilly was sent to the Middle East to investigate reports about large oil resources discovered in Persia. The Royal Navy was contemplating modernizing the fleet by changing from coal to oil for fuel and these resources, if they existed, would be vital to those plans. Reilly reported that the information was factual, but that an Australian, William d’Arcy, had been granted the development concession by the Shah. d’Arcy needed substantial financing to develop the oilfields and was in Cannes working a deal with France and the Rothschilds when Reilly turned up. Disguised as a priest collecting donations for charity, he barged his way onto the Rothschilds’ yacht where the negotiations with the French government were under way.

Taking advantage of the disruption he had caused, Reilly lured d’Arcy away for a private conversation and convinced him on the spot that he could make a better deal with the British government. D’Arcy agreed, and in May 1905, the agreement was made, resulting in the British government holding major shares in the British Petroleum company.

Reilly’s next big assignment was in 1909 in Germany, where he took a job as a welder in the Krupp armament works. Volunteering for the night shift, he was easily able to break into the company’s files and copy the plans for their newest weapons at his leisure. With the situation in Europe worsening, this information on Germany’s armaments industry was of great value to the future British war effort.

Reilly’s Problem Solving Methods Were Nothing Short of Genius

Of equal interest to the British was information concerning Germany’s rapidly expanding fleet. Once again, they turned to Reilly, whose methods in solving the problem were nothing short of genius. Instead of going to Germany to acquire the information, Reilly traveled to Russia, where he managed to persuade agents of the German shipbuilding firm of Blohm & Voss to take him on as a partner. After their disastrous war with the Japanese, the Russians were looking to rebuild their fleet, and in 1911 they began soliciting contract proposals from several foreign shipbuilders. For his plan to work, Reilly needed to establish a good relationship with Russia’s Minister of Marine. He did so by first sleeping with the minister’s wife to gain ready access to their home. Once “inside,” he was able to convince the minister with relative ease to award the building contracts to his firm. As Blohm & Voss’s shipbuilding plans for the Russian fleet were very much similar to those used by the German Navy, Reilly had no difficulty in acquiring copies of German Navy plans without raising German suspicions about his true designs.

When several British shipbuilding firms discovered that Reilly had gotten the contracts for the Germans instead of the British, they considered his actions to be bordering on treason—that is, until the Admiralty began receiving copies of German naval plans. To top it all, with the substantial commissions Reilly received for acquiring the Russian contracts, he paid the Russian minister to divorce his wife, whom Reilly then married. Nadine was apparently Reilly’s second wife and his first bigamous marriage.

His new wife on his arm, Reilly is said to have become a member of the Allied Entente and moved to Japan, where he worked as an agent for the Russo-Asiatic Bank, purchasing Japanese supplies for the Russian Army. In 1914, they moved to New York, where Reilly is known to have had an office at 120 Broadway. While in New York, he is alternately credited with countering German attempts to sabotage American efforts to supply the Allies during the war and purchasing and transporting American supplies for the Russian Army. With the beginning of World War I, Reilly’s services were in high demand. The operations he performed during this time were literally the stuff of legend and have added greatly to his reputation. One of the most amazing was when he disguised himself as a German officer on Prince Ruprecht of Bavaria’s staff and participated in a meeting of the Chiefs of the German High Command with Kaiser Wilhelm himself in attendance!

From New York Reilly moved to Canada, where in October 1917 he joined the Royal Flying Corps. Back in England, Reilly volunteered his services to MI-1c (which became MI6 in 1921) of the British SIS and was accepted as an agent on March 15, 1918. He was given the agent number ST1, which simply meant that his handlers were from the SIS’s Stockholm, Sweden, office. Reilly later claimed to have been working for British intelligence shortly after arriving in London in 1895, but according to MI6 documents, he was not officially hired until 1918.

Reilly Preferred to Have Them Humiliated Than Killed

The Russian Revolution of 1917 had overthrown the Czar, and the British government was concerned that the new regime would try to make a separate peace with Germany. Reilly was subsequently sent to Russia in May 1918 with instructions to try and keep Russia in the war, a seemingly impossible task, especially for one man. In grand fashion, Reilly developed a plan of operation, though it went somewhat beyond what the British government had envisioned. Using British funds, he would buy off the Latvian mercenaries—the only disciplined, well-armed force the Bolsheviks could rely on—who safeguarded Lenin and Trotsky. With the Latvians under his control, Reilly would capture Lenin and Trotsky and then parade them through the streets of Moscow in their underclothes! Reilly did not want them killed —he was afraid that would make martyrs of them—just humiliated enough to break their power. At the same time, he organized a group of socialist counterrevolutionaries who would step in and establish a new government, while Reilly would in fact run the new government from behind the scenes.

Reilly’s operation was proceeding according to plan, generating confusion and casting doubts on the loyalty of the Latvians, when Dora Kaplan’s attempt to assassinate Lenin brought everything crashing down. To further complicate matters, a French journalist sympathetic to the Bolsheviks revealed the plot, putting the British in a very bad light. The Bolsheviks reacted violently, arresting everyone suspected of being an enemy and initiating what became known as the Red Terror. A wanted man, Reilly was forced to flee for his life. “Hiding in plain sight,” he avoided arrest by posing as a member of the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. Despite several close calls, with some assistance he managed to escape Russia and return to England, where he supposedly was awarded the Military Cross for his efforts.

In 1919, he was back in New York, still working against the Bolsheviks. That year, a number of mail bomb explosions took place in the United States. These terrorist acts were said to be the work of the Bolsheviks and a “Red Scare” panic spread throughout the country. Between the time of the mailings and when the bombs detonated, Reilly reportedly left the country. Although there is no concrete evidence, it could be surmised that Reilly may have been involved. At this point the SIS had had enough of Reilly’s anti-Bolshevik actions and in 1921 he was fired from the service. That same year, he and Nadine divorced. Although Reilly was still legally married to Margaret, his first wife, in 1922 he committed his second bigamous marriage, to a young actress he had met in Berlin named Pepita Bobadilla.

For the next several years, Reilly used his numerous connections and literally all of his substantial wealth to help organize and fund anti-Bolshevik resistance groups inside Russia. In 1922, an organization called the “Monarchist Union of Central Russia” (MUCR), which claimed to be a resistance group of prominent White (noncommunist) Russians, was established. The MUCR, known simply as “The Trust,” solicited the financial and moral support of White Russian émigrés throughout Europe and several prominent White Russians were members. The ability of Trust members to come and go through Russia’s restricted borders and their apparent power within the communist regime lent credibility to the organization. The Trust was in fact a cover for an OGPU operation whose purpose was to discover from its unsuspecting members the names of agents inside Russia, identify and neutralize its opponents outside Russia, and control foreign or White Russian agents and propaganda coming into Russia.

Murder or Suicide?

The Trust sent out invitations to leading anti-Bolshevik figures to return to Russia to meet and confer with Trust officials, claiming they had nothing to fear from the Bolsheviks. One such invitation was sent to Boris Savinkov, a former Minister of War, and the man whom Reilly was counting on to lead the counterrevolution he was organizing. Savinkov accepted the invitation and in 1924 reentered Russia at an often used and usually safe entry point along the Russian-Finnish border known as “The Window.” He was promptly arrested by the OGPU, imprisoned, and then killed a few months later. His death was reported as a “suicide.”

Upon hearing of Savinkov’s betrayal and capture, Reilly immediately began looking for a way to strike back at the Bolsheviks. His opportunity came with the Anglo-Soviet Treaty, an agreement initiated by Britain’s first Labor government, which would recognize the Soviet Union and arrange for substantial British loans to help prop up that government. Reilly forged a document addressed to the British Communist Party. Known as the “Zinoviev Letter,” after the head of the Third Communist International, it called for British communists and Labor Party sympathizers to prepare for a communist revolution in Britain. The Zinoviev Letter was released by MI-1c to the local papers a few days before the national elections. It caused an immediate uproar and no end of trouble for the Labor government, which lost the election by a landslide. The letter also caused Anglo-Soviet relations to collapse and even delayed the United States’ recognition of the Soviet Union. The Zinoviev Letter was one of Reilly’s greatest triumphs, and he purportedly said of the affair, “It’s a fake, but it’s the result that counts.”

This was to be Reilly’s last notable success against the Bolsheviks. In September 1925, for reasons that are still unclear, Reilly accepted an invitation from The Trust to come to Russia for a meeting. He crossed the border at the Window and arrived in Moscow, where on September 27 he mailed a postcard to a colleague in the SIS simply stating that “all was fine.” No further communication was received and his whereabouts caused a stir within the SIS. Reilly’s disappearance was front-page news in Britain for several days and numerous attempts were made to discover what had happened to him. The Bolsheviks eventually claimed he had been shot trying to escape over the Finnish border. He had in fact been arrested by the OGPU, interrogated for five weeks, and then murdered.

The Original James Bond?

For years, the search for Reilly continued, with people claiming they had seen him alive in various parts of Europe. Some in the intelligence services even contemplated the possibility, not unthinkable knowing Reilly’s capabilities, that he had cut a deal with the Bolsheviks and was now secretly working for them. His wife, Pepita, believing him still alive and a prisoner of the communists, wrote a book telling his story in an effort to keep the search going. Published in 1933, Sidney Reilly, Britain’s Master Spy: His Story, revealed many of Reilly’s escapades, both real and fictional, and greatly perpetuated his already growing legend. Moscow continued to hide the truth, sticking by its lie that he was killed trying to escape. In 2002, a former OGPU colonel, Boris Gudz, gave an interview to Andrew Cook, author of On His Majesty’s Secret Service: Sidney Reilly ST1, in which he claims to have been part of the unit responsible for interrogating and then murdering Sidney Reilly on November 5, 1925.

Master spy, high-stakes gambler, lothario, and confidence trickster are just some of the names, or perhaps talents, that can be applied to the astonishing Sidney Reilly. In his time, he was undoubtedly the finest intelligence agent in the world, and the British press described him as “the greatest spy in history.” There can be little doubt that he revolutionized espionage, changing it from a “gentleman’s game” to one of harsh reality and cold practicality. Winning at any cost was what was important, the new “name of the game.”

Perhaps the best compliment that could be given him, especially in today’s world, comes from Ian Fleming, who based his creation, James Bond, on Reilly’s exploits: “James Bond is just a piece of nonsense I dreamed up. He’s not a Sidney Reilly, you know!”

A version of the Reilly story was presented as a mini-series on public television in 1983. This was before the fall of the Soviet Union and much of the film was a combination of fact and conjecture. Still, it was quite interesting. A few of the blank spaces in his life have been filled in since but the full story will probably never be told.