By Donald J. Roberts II

When the Civil War started in 1861, there were only two officers in the Union Army who had commanded a force in battle larger than a brigade. They were John E. Wool and Winfield Scott. At age 77, Wool was two years older than Scott and was showing the effects of his age. However, during the war, Wool served with distinction in the Eastern and Middle Departments. Winfield Scott was the general in chief of the army.

A major difficulty at this time was finding officers who were competent enough to organize, administer, and command large armies in combat. The vast majority of young officers—who had never seen a force larger than the 14,000-man assemblage Scott had commanded in the war with Mexico—had only limited experience in commanding small units. Most of these had attended West Point and, as a result, had been trained mainly in the areas of engineering, fortifications, and mathematics. Only a small portion of their schooling had been dedicated to strategic and tactical thought. At the same time, they received very little instruction on how to effectively administer an army or how to organize a group of officers for staff work.

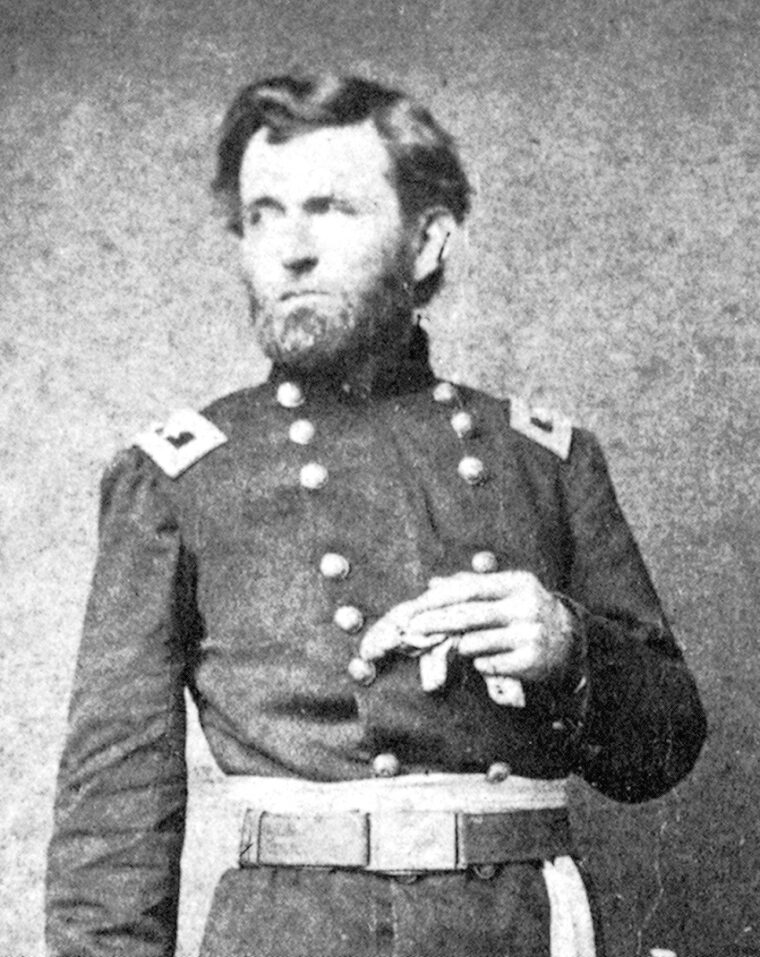

As the Civil War slowly expanded into a major conflict, a number of officers began to demonstrate skills that allowed them to persevere through the early period of the war. Eventually the innate qualities that are so important for good leadership began to propel these men into significant positions of command. Ulysses S. Grant was one.

When Fort Sumter was attacked by the Confederates in April of 1861, Grant was a clerk in his family’s leather business in Galena, Ill. Within one week he began helping the local militia company organize its ranks, and he instructed its officers in proper drill procedures. He even designed the unit’s uniforms. But when the men in the company tried to elect him their company commander, he refused. Grant felt that the rank of militia captain was beneath him because he was a graduate of West Point and had been a captain in the regular army with an excellent combat record in the Mexican War. Realistically, he was holding out for something more worthy of his status.

Grant Receives His First Opportunity of the War

When the Galena company moved to the militia camp of instruction at Springfield, Ill., Grant followed them. He was told at Springfield that there were no command positions available in any of the newly formed regiments. As a result, he accepted the only position he could find, that of a clerk in Governor Yates’ office.

Within a short time, Grant received his first opportunity of the war. John Pope relinquished his command of the instructional camp when a brigade he had been raising did not elect him its commander. With Pope leaving, Governor Yates did not take long to appoint Grant as the new commander of the camp.

As the newly appointed camp commander, Grant performed his duties in fine fashion. In fact, he carried out his responsibilities so well that the officers of the 21st Illinois Volunteers were impressed. The 21st Illinois was a newly formed regiment. Its colonel was incompetent, and the men in his regiment ran rampant around Springfield stealing, drinking, and brawling. Things were so deplorable that Governor Yates was forced to step in. He appointed Grant colonel of the 21st. By June Grant had been promoted to the rank of Brigadier General.

General Grant shaped the 21st into good order in a short period. In July he received orders to take his regiment to the rescue of another Illinois regiment that had become surrounded by a Confederate force in Missouri. Grant did march to the rescue, but it turned out to be a case of wrong information. There was no enemy formation. Later, Grant wrote: “My sensations as we approached what I supposed might be ‘a field of battle’ were anything but agreeable. I had been in all the engagements in Mexico that it was possible for one person to be in; but not in command. If someone else had been colonel and I had been lieutenant-colonel I do not think I would have felt any trepidation.”

Experiencing the Anxiety of Command

Grant’s anxiety about being in command may be best understood by noting that the American Civil War was very different from wars previously fought. Huge armies and advancements in technology combined to cause a tremendous number of casualties on the battlefield. At the same time, the Civil War was very similar to other wars in many ways. One was that commanders were forced to cope with the responsibilities of ordering men into battle (moral courage). Although these same commanders may have possessed high levels of physical courage (leading men into battle), many found it very difficult to send their men against the enemy and remain back to command the field. The commanders along the Illinois-Missouri border—Grant among them—were no exception. They had to come to grips with the issue of moral courage.

In a couple of weeks the 21st Illinois received orders to march again. This time Grant was told to take his regiment and attack a suspected Rebel camp 25 miles away. The enemy assembly was commanded by Colonel Thomas Harris. As Grant marched his regiment toward the enemy, he did not know exactly what was waiting for him: “As we approached the brow of the hill from which it was expected we could see Harris’ camp, and possibly find his men ready formed to meet us, my heart kept getting higher and higher until if felt to me as though it was in my throat. I would have given anything then to have been back in Illinois, but I had not the courage to halt and consider what to do; I kept right on.”

At the end of his march, Grant found that Harris had abandoned his camp. This one march, which resulted in no engagement with the enemy, had a lasting effect on Grant. Because Harris had withdrawn his force, Grant speculated that Harris was “as afraid of him as he was of Harris.” This train of thought deeply affected Grant, and it changed the way he approached battle for the remainder of the war. He would write later, “From that event to the close of the war, I never experienced trepidation upon confronting an enemy.… I never forgot that he had as much reason to fear my forces as I had his.”

As Grant wrestled with these issues, President Lincoln tried to decide who he should appoint to command Union forces along the Mississippi River. In July he decided on John C. Fremont. “The Pathfinder” had limited military experience, but he was a noted explorer of the day. Fremont, who was very well educated, was a hero to millions of Americans because of his exploits in the West. He had discovered Lake Tahoe, scaled the Sierras, named the Golden Gate, and written a book about Mormons moving into the Salt Lake Valley.

With the appointment of Fremont, the Western Department was created. It stretched from Illinois to the Rockies including all states and territories. Initially, a portion of Kentucky was included as well.

The ‘Anaconda Plan’ Aims to Strangle the Confederacy

Within days, Fremont, President Lincoln, and General Scott decided that Fremont’s main strategic objective should be to clear Rebels from Missouri. Once that was accomplished, the next objective (in accordance with Lincoln and Scott’s Anaconda Plan of strangling the Confederacy by controlling its riverine and coastal ports) would be to advance down the Mississippi River and capture Memphis, Tenn.

Grant’s early efficiency and drive had impressed Fremont. Consequently, on August 28 Fremont gave Grant command of the District of Southeast Missouri and Southern Illinois with headquarters in Cairo, Ill. Fremont ordered Grant to eliminate all Confederate forces from southeast Missouri.

During the summer, Kentucky, a slave state, remained “neutral.” In other words, it had not seceded with the original seven slave states that had created the Confederacy before the war’s beginning. Nor had Kentucky left the Union following the attack on Fort Sumter. President Lincoln, not wanting to violate Kentucky’s neutrality, did not want to take any offensive action within her borders for fear of “pushing” her into the Confederacy.

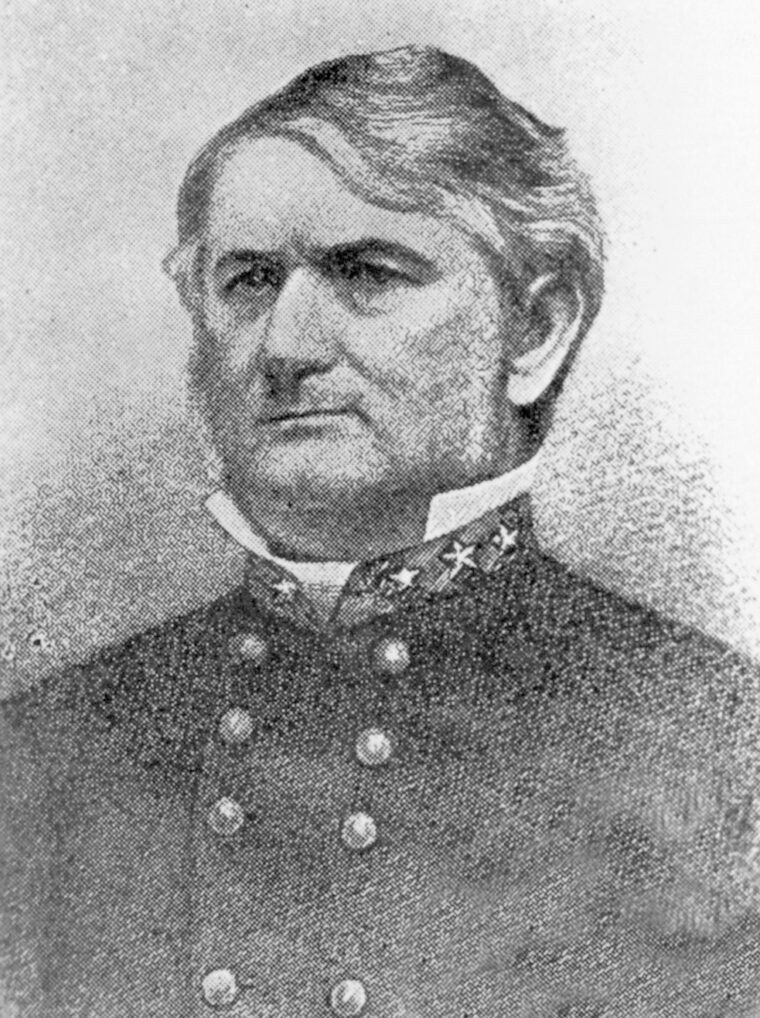

As it turned out, Southern forces were the first to infringe upon Kentucky’s nonpartisan position. On September 3, 1861 General Leonidas Polk ordered General Gideon J. Pillow to capture Columbus, Ky. Many on both sides considered Columbus critical for control of the Mississippi River.

Grant had not even settled into his headquarters at Cairo when he learned of the Rebel occupation of Columbus. He became extremely alarmed by the close proximity of the enemy—Columbus was only 20 miles south of Cairo. At the same time Grant was afraid the rebels would attempt to occupy Paducah, Ky., strategically located east of Cairo where the Tennessee River empties into the Ohio River. If Paducah were occupied by the enemy, Grant knew that the Rebels would be able to interdict all Union shipping along the Ohio River.

By the evening of September 5, Grant had organized a force for advancing on Paducah. Without waiting for orders, Grant loaded two infantry regiments onto local steamships for the move on Paducah. When the Federals reached their target on the 6th, they landed unopposed. Leaving General Charles F. Smith in command, Grant returned to his headquarters to find the orders permitting him to advance on Paducah.

The Rebels Increased Their Strength Daily

Grant’s move to occupy Paducah was a masterful countermeasure to the Confederate occupation of Columbus. In response, Polk ordered Brig. Gen. Frank Cheatham to attack Paducah and drive all Union forces out. General A.S. Johnston countered the order, believing that this move would separate Rebel forces, thus making it too difficult to mass their strength when necessary. Grant believed the same thing, recalling: “They [Confederates] are fortifying strongly and preparing to resist a formidable attack, and have but little idea of risking anything upon a forward movement.”

Rebel strength at Columbus grew stronger each day. This bothered Grant, as it would any commander, but he believed that both his and Polk’s forces were equal in strength and felt that because both armies were similarly disorganized, undisciplined, and untested, the advantage would go to the commander who was the “most active.”

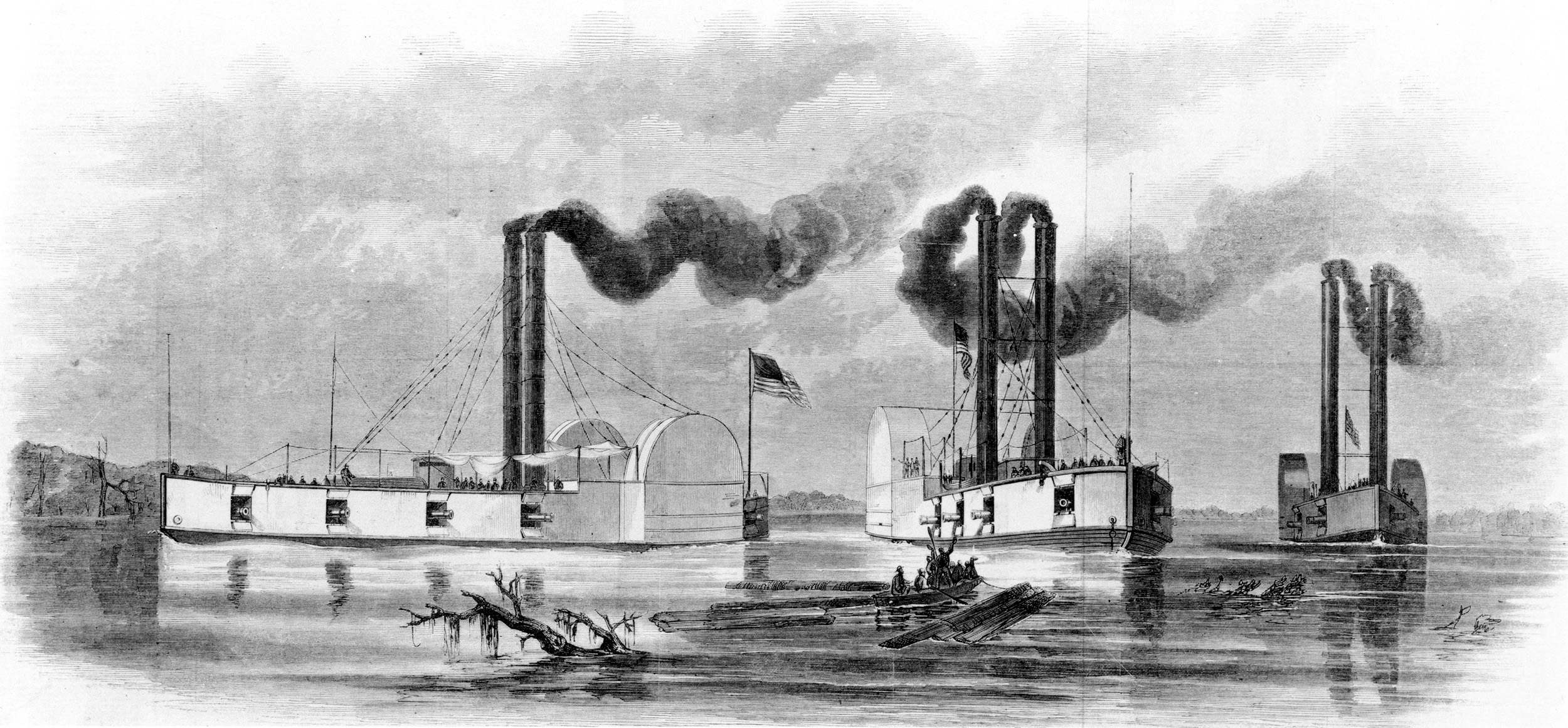

On September 8, Grant ordered the gunboat Lexington south from Cairo to make a reconnaissance of Confederate strength at Columbus. As the solitary Union gunboat steamed within range of the Rebel fortifications on the bluffs at Columbus, the defenders opened fire. Following an exchange of cannon fire, the Lexington withdrew northward back to Cairo.

During the weeks that followed, Grant continued to probe Rebel positions with naval and infantry forays along both banks of the Mississippi. His dislike of growing Confederate strength increased as fast as their reinforcements arrived. He wired Fremont in St. Louis for permission to strike Columbus and capture the Rebel stronghold.

140 Pieces of Artillery Trained on the River

On November 1, 1861, Grant received orders from Fremont. He was instructed to “demonstrate” against the Rebel stronghold at Columbus sufficiently to prevent Polk from sending any reinforcements to General Sterling Price in Missouri. From these orders, Grant decided to conduct full-scale offensive operations against the Confederate positions at Columbus.

Almost overnight, Columbus had grown into an overpowering Confederate position on the Mississippi River. The bluffs along the river soared nearly 150 feet high. Along the shoreline at the bottom of the bluffs, the Rebels had entrenched a number of 10-inch Columbiads and 11-inch howitzers. Halfway up the embankment the defenders had dug in a second line of artillery. On top of the heights, the Confederates had constructed a series of earthwork forts. One of the forts held the largest artillery piece in the Confederate arsenal, a 128-pound Whitworth rifled gun. The gun’s crew nicknamed the piece “Lady Polk.” These commanding bluffs became known as the “Gibraltar of the Mississippi.” There were nearly 140 pieces of artillery trained on the river, and the entire defensive position was garrisoned by 17,000 troops.

Grant’s gunboat forays against Columbus had given him a picture of his enemy’s strength. Owing to the rapid buildup, Grant decided to attack Belmont on the Missouri side of the river instead. Belmont was directly across from Columbus and was not nearly as well defended as the “Gibraltar of the Mississippi.” Grant hoped to surprise the small Confederate force there.

He decided to use two brigades of infantry for his primary attack. One brigade was under the command of Brig. Gen. John McClernand, and the other under Colonel Henry Dougherty. In support of the infantry were two companies of cavalry and a light battery of artillery. In order to transport his force down river, Grant gathered six steamers and two gunboats. In all, Grant’s force numbered 3,114 men.

Grant’s Gamble

Grant planned on implementing several secondary actions in order to try to confuse Polk. He realized he was dividing his command in the face of a formidable enemy, but he considered the reward worth the gamble.

On November 5, Grant put his plan into action. He cabled General Smith at Paducah ordering him to demonstrate toward Columbus. Grant wrote that a movement toward Columbus from Paducah “would probably keep the enemy from throwing over the river [Mississippi] much more force than they now have there, and might enable me to drive those they now have out of Missouri.” Grant believed Smith’s demonstration would prevent Polk from sending reinforcements across the river to fall upon his rear and cut his lines of communication with Cairo.

In order to coordinate his move with Grant’s, Smith prepared his command to move on the 6th. He sent one brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. Eleazer Paine toward Milburn, Ky. In order to cover Paine’s left flank, Smith directed one regiment under Colonel W.L. Sanderson to move toward Viola. Grant ordered a third diversionary force to move along the east bank of the river. These orders were sent to Colonel John Cook. His brigade was to demonstrate down the river but progress no closer than Elliott’s Mills.

On the west side of the river in Missouri, Colonel Richard Oglesby’s brigade was ordered to march his command from Sikeston south to New Madrid, which was located on the river south of Belmont. Grant directed Oglesby to “halt and communicate with me at Belmont from the nearest point on the road” as he marched toward New Madrid. To cover Oglesby’s left, Grant ordered Colonel William Wallace’s 11th Illinois to conduct the covering march.

All told, Grant’s total force numbered some 15,000 men. Virtually his entire command would be moving at once. Although his forces were separated, they were not divided so widely as to not be able to be massed together if the need arose. One thing was certain: The multiple columns that Grant put into motion certainly made it difficult for Polk to determine Grant’s main objective.

On the afternoon of the 6th, Grant prepared his force at Cairo for embarkation upon the steamboats that would transport his brigades to Belmont. By 3 pm, two of McClernand’s regiments, the 30th and 31st Illinois, began loading onto the steamer Aleck Scott. McClernand’s third regiment, the 27th Illinois, moved aboard the James Montgomery. Colonel Dougherty’s 7th Iowa loaded on the Montgomery with the 27th, and Dougherty’s second regiment, the 22nd Illinois, boarded the Keystone State. Grant’s artillery and cavalry loaded onto the steamers Chancellor and Rob Roy.

Green Soldiers Struggle to Sleep Before the Battle

Covering Grant’s waterborne force were the gunboats USS Lexington and USS Tyler. As Grant’s multiple diversionary units began to move toward their intended objectives, Grant’s force departed from Cairo for its journey south down the Mississippi.

The Union flotilla pressed south until 11 pm. Grant then decided to tie up along the eastern bank of the river about 11 miles above Columbus and wait out the night. He posted a strong guard on shore while the remainder of the men tried to sleep. Most of Grant’s men had never tasted battle; as a result, sleep for many was nearly impossible. To make matters worse, word had spread that they were on their way to assault the strong fortifications at Columbus.

On board the Belle Memphis, Grant received a message from Wallace, who was covering Oglesby’s eastern flank, that he “had learned from a reliable Union man that the enemy had been crossing troops from Columbus to Belmont the day before for the purpose of following after and cutting off the forces under Colonel Oglesby.” This message convinced Grant that he had made the correct decision in attacking Belmont.

In fact, Grant realized his campaign now had two objectives: protect Oglesby’s eastern flank and, as first understood, stop General Polk from reinforcing Price west of the Mississippi.

Grant immediately issued a Special Order. It read: “The troops composing the present expedition from this place, will move promptly at six o’clock this morning. The gunboats will take the advance and be followed by the 1st Brigade under the command of Brigadier General John A. McClernand, composed of all the troops from Cairo and Fort Holt. The 2nd Brigade, comprising the remainder of the troops of the expedition, commanded by Colonel John Dougherty, will follow. The entire force will debark at the lowest point on the Mississippi shore where a landing can be effected in security from the rebel batteries. The point of debarkation will be designated by Captain Walke, commanding Naval Forces.”

By 6:30 on the morning of November 7, the Union fleet released the lines holding them to the Kentucky shore and proceeded downriver toward the objective. Grant felt confident. He believed that any Rebel troops west of the river would be caught by surprise by his attack. If he was really lucky, Grant felt he might even take them in their flank. At the same time, Grant embraced the idea that his demonstration on the east side of the river (Paine and Sanderson) would prevent Polk from rushing too many troops across the river against him at Belmont.

Scattered Musket Shots Began Peppering Grant’s Men

As Grant’s naval force steamed southward, he went up to the pilothouse to inquire how close his landings could take place “out of sight of Columbus.” Pilot Scott replied, “About three miles north at a landing at Hunter’s Farm.” Scott emphasized, however, that the landing was out of sight, but it was not out of range of the guns at Columbus.

It was nearly 8 o’clock when the landing at Hunter’s Farm came into view, and the transports began tying up on the Missouri side of the river. Officers promptly began barking orders to disembark and form ranks on shore. Within minutes, scattered musket shots began peppering Grant’s men from a dense tree line. Heavy return fire from troops still on board the transports drove off the handful of enemy soldiers. As the unloading continued, Grant ordered Commander Henry Walke to proceed downriver with both gunboats in order to draw enemy fire away from the landings.

This Walke did by 8:30. Although heavily outgunned by the strong shore defenses, the Lexington and Tyler did draw some fire from shore. However, the majority of the Rebel fire was directed toward the transports. Concerned for the landing force, Walke withdrew back to Hunter’s Farm and ordered the transports out of range of Columbus’s guns as soon as the offloading was complete.

Soon Walke could hear firing from shore as the volume increased in intensity. He decided to make another run toward the “Iron Banks” at Columbus. This second attack lasted 20 minutes. The few shots his gunners fired at the hidden positions on shore were no match for the volume of fire Walke’s two gunboats received. Walke stated that it “would have been too hazardous to have remained long under [the enemy’s] fire with such frail vessals [sic].” Walke steamed upriver out of range once again.

The Battle of Belmont Begins

The beginning round of the Battle of Belmont had begun. Earlier in the morning, at 2 am, General Polk had been awakened and informed of Grant’s demonstrations east of the Mississippi. After dawn Polk was told that Union gunboats were on the river and that transports were unloading men on the west bank in “considerable force.” Polk decided to send General Pillow across the river with his division to “take charge of the situation.” But Polk remained convinced that the Union’s primary attack would be on the east side and that it would be directed at Columbus.

Fortunately for Pillow, there were a number of transports near Columbus available to ferry his men across the river to reinforce Colonel James Tappan, who commanded Camp Johnson at Belmont. Tappan had the 13th Arkansas, a battalion of cavalry, and a battery of artillery. Pillow was bringing across four regiments from Tennessee: the 12th, 13th, 21st, and 22nd. By 10:30 in the morning Pillow had all four of his regiments across and in formation. By that time Grant’s force had been on the move from Hunter’s Farm toward Belmont for nearly two hours.

Before moving on the Rebel camp, Grant quickly selected five companies of infantry from Dougherty’s Brigade to guard the landing and protect the line of communication. Grant had to position this force personally because he believed that he did not have a line officer with sufficient experience to command this “ad hoc” battalion.

Grant placed this group in an excellent spot. It protected his rear and flank from attack and provided cover from artillery fire from “Iron Banks.” Grant regarded this position as “a natural entrenchment” from which the battalion “could hold the enemy for a considerable time.”

Hoping that he could still achieve surprise, Grant formed his force for the march through the heavy timber and thick cornfields that stood between him and the enemy camp. As the Union forces moved through the warm morning sunshine toward Belmont, an occasional artillery round fired from “Iron Banks” would crash among the trees. Confederate gunners across the river were trying to find Grant’s column amid the dense river-bottom growth of forest and underbrush.

Except for the sporadic artillery fire, the march toward the enemy camp was fairly easy. Bits of marsh and swamp in the often-flooded terrain slowed the Union column at times; however, the road Grant’s men followed was in good shape overall.

As Captain James Dollins’ Union horsemen swept the line of march, Confederate cavalry from Lt. Col. John Miller’s 1st Mississippi Battalion engaged them and quickly broke away again. Dollins reported that the enemy seemed more interested in “observing than fighting.”

But as Grant’s force approached what appeared to be a large slough, Rebel defensive measures increased. Dollins reported that Confederate fire was heavier and that his men were seeing infantry for the first time, though he was continuing to push them as he advanced.

“My Heart Kept Getting Higher and Higher Until it Felt to Me as Though It was in My Throat.”

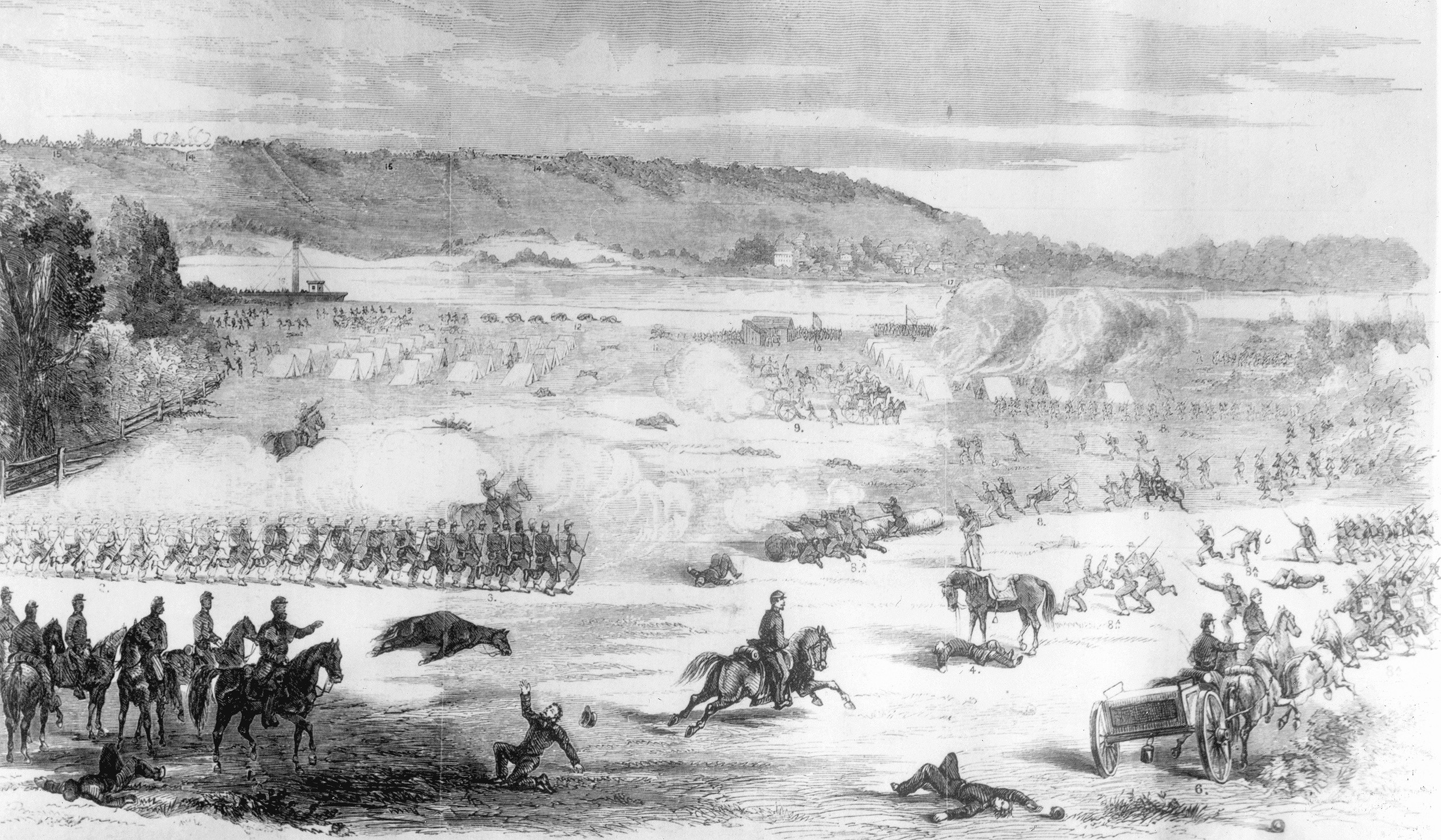

At this point, Grant met with McClernand and decided to deploy the column. A cornfield alongside the road was used to form the men into a battle line. At this location all that Grant’s men had to do was face left in order to face their intended objective, still about two miles away. Grant positioned Captain Ezra Taylor’s artillery pieces in the center and on the left flank of his line, which stretched for nearly half a mile.

Orders were then given to each regimental commander to deploy two companies forward as skirmishers. Specifically, they were “to seek out and develop the position of the enemy.” As the skirmishers advanced across the slough, they encountered thick woods on the opposite side. Confusion reigned. All of a sudden it became very difficult for officers to maintain alignment. Once inside the tangled woods, the inexperienced Union infantry began to hear the “long roll” of Confederate drums at the enemy camp ahead. Cautiously the Union line continued to move forward as best they could in the dense foliage. Grant himself remembered his feelings from July when he had maneuvered to attack Harris’s camp: “My heart kept getting higher and higher until it felt to me as though it was in my throat.”

The first portion of the Union line to receive heavy fire from the enemy was the right flank. Grant had assigned Colonel Napoleon Buford’s 27th Illinois to that section of the line. As the firing increased, McClernand ordered Colonel Philip Fouke’s 30th Illinois forward to support Buford’s 27th. Soon the firing became so heavy that Grant ordered his regiments on the left to alter their advance and move to “the sound of the firing.”

Within minutes, the firing became intense, despite the fact that owing to the dense underbrush and heavy woods, it remained very difficult for the armies to see each other. The fighting rapidly became very disjointed. Often command was maintained only within the smallest tactical unit within each company. Nevertheless, the nerves of Grant’s men “grew stronger” when they were told to “take trees and fight Indian fashion.”

Eventually, the fighting was so uncoordinated that McClernand stopped Buford’s advance and ordered him to maneuver farther to the right to “feel the enemy and engage him if found in that direction.” This left a gaping hole on the Union right, which was filled by the 22nd and 31st Illinois regiments and the 7th Iowa.

Pillow Attempts a Desperate Bayonet Charge

Although Pillow’s skirmishers held good positions in the dense woods, they were constantly being enveloped by the steadily advancing Yankees. By 11 in the morning Pillow’s men had all been forced to withdraw, reform their ranks, and rejoin the main Confederate defensive line along a low ridge between the heavy timber and Camp Johnson.

As the Union regiments began to advance out of the woods and toward the main enemy line, Confederate fire began to decrease. Pillow’s men began to run low on ammunition, especially along the Rebel right. As a result, Pillow ordered a bayonet charge.

General Pillow knew from his experiences in the Mexican War that the bayonet “had ultimately settled the issue on the battlefield.” But this time it did not; the Federals recoiled but did not flee. Following a brief Union withdrawal, Colonel John Logan’s 31st Illinois tried several times to turn the Confederate right flank. These determined Federal attacks forced the Rebels to drop back to their original line and forced them to use up more of their precious ammunition.

Slowly, the Union advance along the Confederate right began to push the defenders back toward their camp.

In the center of Grant’s attack, Colonel Jacob Lauman’s 7th Iowa and Fouke’s 30th began to break out of the heavy timber as well. This advance was answered by Lt. Col. Daniel Belzhoover’s Watson Battery. The Rebel artillery opened up on the advancing Union troops and forced them back into the tree line. Once back under cover, Lauman told his men to “fall on the ground.” He then shouted, “Crawl boys,” and the Union line began to advance again.

Because the Rebel artillery fire had only momentarily slowed the Union advance, Pillow rode up to the center of his line, held by Colonel Edward Pickett’s 21st Tennessee and Colonel Thomas J. Freeman’s 22nd Tennessee, and asked if “we could not charge and drive the rascals out.” The order of “Charge bayonets” filled the air.

In a rush, Rebel infantry charged the blue line and pushed them back into the woods. Although surprised and confused, the men of the 7th Iowa and 30th Illinois recovered and, through concentrated volley fire, forced the Rebels to withdraw in the center of their line.

Collapsing the Confederate Line

Beltzhoover’s guns raked the Union tree line, which allowed the 21st and 22nd to withdraw in good order. But just then Taylor’s Chicago Battery came up to the line. Within minutes, Rebel and Union artillery were engaged in a spirited exchange of gunfire that brought about the collapse of the entire Confederate line. With Pillow’s right already retiring, the heated artillery duel collapsed the remaining portion of the Confederate line.

As Pillow’s main line began to fall back into defensive positions at their camp, Buford’s 27th Illinois moved southward and came up on the extreme left flank of the Confederate camp in a classical envelopment maneuver. Slowing Buford’s advance momentarily was Company A, 13th Tennessee, which had been left back as a camp guard.

Pushing on, the 27th assaulted across the camp’s parade ground but then withdrew due to withering volley fire by the defenders. As Buford’s men prepared for another assault, the 7th Iowa and 22nd Illinois advanced and fixed themselves on his left. At the same time, Taylor positioned his battery in the center of Grant’s line and began to fire canister shot into the camp. Fouke’s 30th and Logan’s 31st advanced and began to envelop the camp on the north as well.

With Federals streaming into camp from three directions and a steady pounding by Taylor’s guns, Pillow had no choice but to order the retreat from Camp Johnson. Almost immediately, the entire camp began fleeing north along a lane that paralleled the river. As the retreating Rebels ran, they braved a gauntlet as “hundreds of Union muskets poured their deadly content.” Men from each of Grant’s five infantry regiments began chasing the Confederates in a loosely organized pursuit led by Colonel Lauman. It continued for nearly a quarter mile and then slowly stopped after Lauman was hit in a thigh by a musket ball as Rebel defensive fire increased along the riverbank.

Viewing the fight from across the river, Polk realized that he needed to send reinforcements quickly to support Pillow. One of the first units across the river was Colonel Knox Walker’s 2nd Tennessee, and it was Walker’s regiment that stopped the Union pursuit of the fleeing Rebels out of the camp. But as Walker began to pressure Logan’s 31st on the north end of the camp, Taylor’s guns came up once again and began to smash huge holes in Walker’s line of men. At the same time, Taylor’s guns began to pour their deadly fire into the Rebel steamers Prince, Hill, and Charm, which were all bringing reinforcements from Columbus.

By around 2 in the afternoon, all firing in and around the captured Rebel camp had stopped. Immediately, Grant’s men began celebrating their victory. All of a sudden, the atmosphere turned to one of hilarity with men running around searching for souvenirs, singing patriotic songs, and firing volleys into the air. General McClernand even found time to mount a tree stump and deliver an “impromptu victory speech.”

After Victory, the Union Troops Became an Uncontrollable Mob

As the minutes ticked by and the looting continued, Grant realized his fighting force had become an uncontrollable mob. In order to stop the looting and gain control once again, he ordered Camp Johnson to be burned. As the fires raged throughout the camp, officers began to organize their men into formations. Unfortunately for Grant, many of the burning tents contained sick and wounded Rebel soldiers who had gone unnoticed by Union torch bearers. Many of the Confederates burned to death. The horrible incident became a “rallying cry” for many Rebels for the remainder of the day.

On the heights across the river, General Polk had witnessed the Federal assault on Camp Johnson and the ensuing panic that had resulted in the hasty retreat northward along the river. After some thought, Polk decided to commit his reserves to the fight in order to somehow salvage the day. At the same time, he ordered a heavy bombardment upon the camp.

This accurate Confederate artillery fire from “Iron Banks” helped Grant to bring control to his force. Thinking that if they stayed around any longer, Rebel gunners from across the river would reduce their ranks in a short time, the men began to form their lines for the march out of the enemy camp.

To add to the reinforcements already sent, Polk ordered Brig. Gen. Frank Cheatham across the river with the 15th Tennessee and the 11th Louisiana in order to reinforce Pillow’s command. To avoid Taylor’s Chicago Battery, the Prince steamed upriver with Cheatham’s force to find a suitable landing somewhere between Camp Johnson and Hunter’s Farm.

“Anxious to Again Confront the Enemy”

Once across the river, Cheatham found that Pillow had organized a force, about brigade size, of elements from all his regiments. Cheatham had brought a large supply of ammunition with him, and it was quickly distributed throughout the ranks. All told, this “reconditioned” Rebel force numbered between 1,000 and 1,500 men, and they were “anxious to again confront the enemy.”

At Camp Johnson, Grant’s men were formed but still hiding in the trees from the gunners on “Iron Banks.” At a few minutes past 2 pm, a lieutenant from Fouke’s regiment reported to Grant that enemy transports were bringing reinforcements across the river. Grant, seeing the boats for himself, gave the orders to assemble and begin the march back to Hunter’s Farm.

Once assembled, McClernand’s Brigade took the lead followed by Dougherty’s Brigade. All at once, firing broke out on the Union right. The entire Federal column, almost to a man, was amazed that the Confederates could mount a determined counterattack since, only an hour before, they had been wildly running out of control along the river.

The spirited Confederate advance, organized by Cheatham, began to destroy McClernand’s hastily formed line. Shouts of “We are flanked” and “They’re surrounding us” began to ring out up and down the Union line. The 7th Iowa became nearly enveloped at the end of the Union column. Because Lauman was down with his thigh wound, Major Elliott W. Rice commanded the 7th and broke it out of the trap.

Grant Finds Himself Surrounded

Still trying to keep Rice pinned at the rear of the column, Cheatham swung his force around and tried to envelop the head of the Yankee column as well. Within minutes, cries of “Surrounded, Surrounded” filled the air throughout McClernand’s Brigade. It seemed like all eyes began to fall upon Grant. He simply stated, “We cut our way in so we can cut our way out.”

As Cheatham’s defense at the head of the Federal column stiffened, McClernand called up a battery of Taylor’s artillery. Within minutes, Taylor’s guns began pouring fire into the center of the Rebel line “with great spirit and effect.” Round after round of double canister was unleashed upon the enemy. McClernand shouted to Logan to take his regiment and “cut your way through.” With a flourish of his hat, Logan led his men forward, ordering the colors to the head of the column.

Logan’s 31st and Fouke’s 30th broke through the enemy line in good order. But as the Union men hurried onward, the column became fragmented. Grant rode to the head of the column at this point so he could personally alert the rear guard to action. They were nowhere to be found. As elements of the 30th and 31st began to hasten past, the rear guard had abandoned their position and had reembarked upon the waiting transports.

By this time, Cheatham’s men were cutting the 22nd Illinois and 7th Iowa to pieces at the end of the Union column. Taylor’s artillery tried in desperation to “make a stand” but they could not stop the pursuing enemy. Eventually, the 22nd and 7th were able to reach the Hunter’s Farm Road for their march back to the landing, but it was costly.

Most of Buford’s 27th Illinois left the retreating Union column and retraced its route from earlier in the day. Traveling on roads that the Rebels did not even know existed, Buford’s regiment came out of the woods three miles above Hunter’s Landing.

Across the river, Polk felt compelled to act further. He personally crossed the river and brought two more regiments with him to reinforce Cheatham. But not doing so earlier probably cost Polk the day. Although Cheatham and Polk got their men moving after the retreating Federals, it was not soon enough. The delay gave Grant the additional time he needed to embark his command at Hunter’s Landing.

“A Perfect Storm of Death”

But as the steamers began to pull away from the shore, the Rebels hotly increased their fire upon the departing vessels. In return the Lexington and Tyler came up and poured a murderous fire onto the bank. They “poured a perfect storm of death into the rebel masses.… whole ranks mowed down by a broadside.”

Onboard the Memphis, Grant heard the increase in fire and walked out on deck. All five transports were in line and the troops onboard were firing “with terrible effect” and “great spirit.” Even Taylor’s Chicago artillerymen had gotten into the action and were firing their guns from the deck of the Chancellor.

Except for picking up Buford’s 27th three miles upriver, the Battle of Belmont was over. During the dark trip back to Cairo, doctors onboard the transports treated the wounded as best they could. Many officers remembered the trip as “solemn.” Grant chose to remain by himself and “said not a word but to a waiter.” But when the Federal armada reached Cairo about 9:30 that night, the city was totally lit up in celebration. Later and into the next morning, Grant recalled all of his diversionary units from both sides of the Mississippi.

Both sides claimed victory following this battle along the Mississippi River. Discussions, arguments, and heated debate were to continue for many years about who won the fight.

Casualties on both sides were fairly even. Grant lost a total of 610 men killed, wounded, and missing. Polk lost 641.

Polk’s defense of Camp Johnson was deplorable. He left the most likely approaches to the camp almost totally unguarded and was not aware of other approaches used in Buford’s envelopment from the south.

There is little doubt that Grant obtained the element of surprise at Belmont. Many believe that Polk was completely confused by Grant’s diversions on both sides of the river. Whether by purpose or not, tying up on the east bank of the river the night before the attack was a masterful stroke by Grant. It was the main reason for the piecemeal reinforcement of Camp Johnson during the attack. Polk clung to the idea that Grant’s true objective was Columbus.

Artillery played a significant role. Although Beltzhoover’s Watson Battery did not distinguish itself on the field, Taylor’s Chicago Battery did. Taylor’s men demonstrated the advantage that may be gained from a highly mobile field artillery unit. During the battle, they seemed to be everywhere and were delivering decisive fire upon the enemy time and time again.

Reviewing Grant’s Mistakes

The Rebel guns at “Iron Banks” played an important role by keeping Walke’s gunboats away from supporting Grant’s attack on Camp Johnson. They also kept Walke’s gunboats from interfering while Polk sent boatload after boatload of reinforcements across the river into the fight.

Grant’s use of naval forces was good. Joint army and navy operations of transportation, embarkation, and disembarkation went as well as could be expected in these early days of the war. Perhaps the biggest mistake Grant made in the use of the navy was his failure to communicate effectively with Walke once Grant’s force had been put ashore at Belmont. If Grant had informed Walke of the heavy concentration of Rebel reinforcements coming across the river, Walke might have been able to disrupt this flow. In defense of Grant, however, Walke should have paid more attention to the fighting on shore and understood what the Confederates were doing.

Possibly the most significant outcome of the battle was bringing Grant’s name to the attention of President Lincoln. At a time when finding true leadership for his fighting forces was a definite concern, Lincoln was impressed with Grant’s initiative and speed of attack.

Grant did make mistakes, however. He violated a vital principle of the offense by not pushing through the objective (Camp Johnson) and then securing his prize. At the same time, Grant has been criticized for not maintaining tighter control over his command. For example, failing to utilize his boat guard (reserve) in the battle was a big mistake. And as already mentioned, tighter control of Walke’s gunboats could have been decisive. In addition, Dollins’ cavalry and Buford’s erratic maneuvers caused some concern during the battle. But again in Grant’s defense, Buford’s flanking move enveloped Pillow’s left at Camp Johnson and probably forced the Rebels to abandon their camp faster than any other aspect of the Union attack.

Preparing for Victory As Well As Defeat

Overall, Grant utilized his “volunteer” officers effectively, and they rose to the task many times during the battle.

General Grant came away from the Battle of Belmont with a better understanding of combined arms warfare. Although he made mistakes, he later proved he had learned from them. In addition, he discovered a new and profound understanding of himself, especially under the muzzle of his enemy’s muskets. But perhaps Grant’s greatest lesson was that a commander must always be just as prepared for victory as he is for defeat.

The battle of Belmont clearly indicated how important Columbus was. As long as the Rebels held the Iron Banks, they controlled the Mississippi. Belmont certainly served as a diversion that left the Rebels unprepared for General Grant’s attacks on Fort Henry and Fort Donelson.

When Fort Henry and Fort Donelson fell, Columbus became outflanked by the Union forces. As a result, the Confederates were forced to abandon their strong position at Columbus. Union forces moved in and occupied Columbus on March 4, 1862.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments