By Keith Milton

First Sea Lord Admiral Sir Dudley Pound stopped tapping his pencil on the oaken desk and slowly leaned backward in the oversized leather chair. With his head now fully back, he closed his eyes and tried to relax his body even more. He had a tough decision to make about arctic convoy “PQ 17”. The room was quiet except for the ticking of the brassbound ship’s clock on the wall behind his chair. After a half-minute passed with no further sound from the supine admiral, one of the junior staff officers nudged his companion.

“His Lordship’s dropped off.”

No one knows if the whispered comment was overheard or not, but the admiral then leaned forward and picked up a message pad. As he began to write, he announced his decision. “The convoy is to be dispersed!”

A half-dozen jaws dropped collectively. Only one of Admiral Pound’s staff had been in favor of this action; his immediate second in command, Vice Admiral Sir H.R. Moore. All the rest had counseled keeping the convoy together, or at the very least, delaying the dispersal until more information became available. Admiral Pound completed his writing and then raised both palms from the wrist at the unspoken objections of his staff. The meaning was clear. The decision was his and was final. Thus was sealed what may have been one of the worst tactical blunders on the Allied side during World War II—it brought about the largest one-day ship loss on the high seas on either side during the war.

The Origin of the Name “PQ 17”

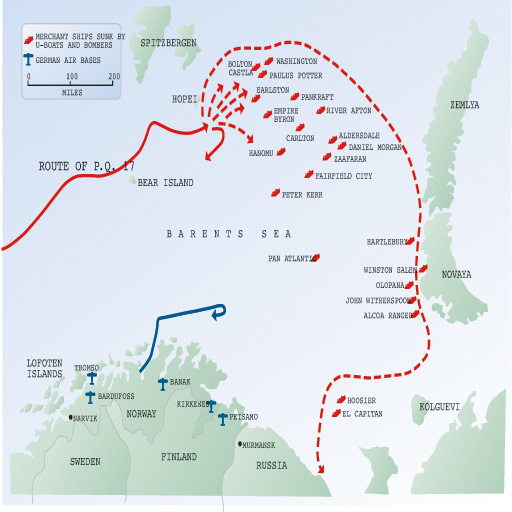

The decision to dispatch Convoy PQ 17 at all had been controversial. (P.Q. was the designation given to the Iceland-to-North Russia convoys, and were so called because Commander P.Q. Richards had the job of writing assembly and operations orders for them.) There was no sound military reason to continue the terrible losses being sustained by the North Cape runs. This had been a concern only since the beginning of 1942 when German presence began to make itself felt in northern Norway.

During the final six months of 1941, 12 convoys had made the passage with the loss of only one ship out of the 103 dispatched. It seemed too good to be true for the Allies, which in fact it was, because the German buildup in Norway intensified with the coming of spring weather. The Germans feared an Allied invasion of Norway, and they also wanted to choke off the flow of war materiel to Stalin’s Red Army.

For their part, the Allies had two principal reasons for continuing the flow. First and most obvious was the need to arm Russia’s huge manpower reserves, which would tie down large German armies. Second and perhaps even more important was the Allied fear that Stalin might conclude a separate peace with Hitler. The spring of 1942 saw the resumption of the German offensive in Russia, and it was going well for the Wehrmacht. In Africa Rommel had taken Tobruk and was inside Egypt. Alexandria was being evacuated and even Cairo was considered threatened. Should the Afrika Korps succeed in defeating the British Eighth Army, there would be nothing to stop a linkup through Palestine and Syria with the German Armies in the Caucasus. This would seal the fate of Russia, and Stalin was well aware of it.

The German Plan to Decimate Allied Merchant Fleets

The dire situation allowed Stalin to demand everything and concede nothing. He continued to press for the dispatching of the PQ convoys, but refused to provide air cover over the Barents Sea. He also refused to furnish destroyer escort from the Russian side of the North Cape to the Kola Inlet, or to allow the British to set up a command post north of Murmansk to co-ordinate the defense of the convoys. The Allies swallowed all this because they had no choice. They knew that Stalin was capable of anything, and even though he hated Hitler, he had signed a pact with him once—before the German invasion of Poland—and might well do so again if conditions proved advantageous.

Hitler believed that Germany’s best hope of victory lay in decimating the Allied merchant fleets. Britain was an island and depended entirely upon shipping for her conduct of the war, indeed for her actual survival. The new enemy, the United States, was three thousand miles away and could not bring her productive capacity to bear without ships. Churchill’s greatest fear was that Allied merchant tonnage might be sunk faster than it could be built, and thus leave the United Kingdom isolated.

Accordingly the German General Staff began the buildup of forces just after New Year’s 1942 by transferring the new battleship Tirpitz from the Baltic to Trondheim, Norway. She was sister ship to the now famous Bismarck and was considered to be one of the most modern and powerful warships afloat. The Royal Navy held her in even greater awe since their Intelligence had discovered that the Bismarck had gone down in May 1940, not as a result of the damage inflicted on her by the large task force sent against her, but by scuttling when she could no longer be steered. Her main armor was still intact when Admiral Lutjens ordered her scuttled to prevent capture by the British.

A month after the Tirpitz arrived in Norway, two more battleships, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, together with the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, were ordered to break out from Brest, France, and join Tirpitz. They made good their escape, steaming northeast through the English Channel, and managed to avoid detection by the Royal Navy. During the dash, however, both battleships struck mines and had to put in at Kiel for repairs. Ill fortune continued to dog the Germans as the Prinz Eugen, having been joined by another heavy cruiser, Admiral Scheer, had her steering gear damaged by a prowling British submarine and had to return to the Baltic for repairs. For the present, only the Tirpitz and the heavy cruiser Admiral Scheer along with their destroyer screen would be available for use against the Russia-bound convoys.

An Attack of 25 Albacore Torpedo Planes

On March 1, 1942 Convoy PQ 12 composed of 16 ships departed Iceland en route to Murmansk. Five days later Germans spotted the convoy nearing Jan Mayan Island and the Tirpitz was alerted. She sortied within 12 hours along with three destroyers but was detected almost at once by a British submarine on patrol, which reported her course and speed to Whitehall. The Admiralty notified Admiral Sir John Tovey, the Home Fleet Commander, at sea with his fleet, who had the tasks of both covering the North Cape convoys and preventing a breakout into the open Atlantic by German heavy ships. He sent the battleship King George V and the aircraft carrier Victorious eastward to meet the threat. An Arctic snowstorm moved in, and for three days neither side was able to locate their quarry. When the weather cleared, scout planes from the Victorious located the Tirpitz and called in a strike.

Tirpitz was already heading back to Norway, having been warned of the approaching heavy ships being sent against her. (Unknown to the British, the Germans had broken Admiralty ciphers as early as June 1940.) Captain Karl Tropp ordered his formidable flak batteries manned just as a swarm of 25 Albacore torpedo planes appeared and commenced their attack. Four separate ones were made, two of them simultaneously, through a veritable firestorm of flak from Tirpitz’s 16 four-inch, 16 twin 40mms, and 48 20mms. She seemed to be literally surrounded by torpedo tracks and on fire from the blaze of her own flak guns, but by incredible good fortune, she passed through unscathed.

The British dive-bomber squadron failed to link up with the slower Albacores for a coordinated strike, arrived too late, and lost the Tirpitz in a fog bank near the Lofoton Islands. It had been a near thing and was to affect the thinking of the German General Staff in the months to come. Hitler himself would order that no heavy ships should sortie without knowing the exact location of the British aircraft carriers and having sufficient air cover. Because the only German aircraft carrier, the Graf Zeppelin, was not yet fitted out, this would have to be done by the land-based aircraft from the North Cape airfields. More Luftwaffe Staffels were moved north as the weather improved.

Success Emboldens the Nazi Navy

U-boat activity was also ordered increased, and the famed Eis Teufel (Ice Devil) squadron was formed up to operate exclusively in the Barents Sea. On March 21, the new heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper completed her trials and left the Baltic to join Tirpitz at Trondheim. The next Russia-bound convoy in the series, PQ 13, was attacked on March 28 by three German destroyers, the heavier ships not being used owing to a fuel-oil shortage.

While the convoy escorts were busy fending off this surface attack, about a quarter of the merchant vessels were lost to U-boat and air attack. One British cruiser, Trinidad, was struck by a torpedo (one of her own as it turned out), and the British destroyer Eclipse was put out of action by surface fire. The Germans suffered no losses. Flushed with this success, they resolved to increase their efforts against the North Cape convoys.

PQ 14 sailed from Iceland on April 12, but 14 out of the 23 ships suffered ice damage and had to return. They had been trying to skirt the Luftwaffe circle of air superiority and had run into heavy field ice. PQ 15 had little better luck and lost five out of 20 ships. In addition, the British cruiser Edinburgh was hit and disabled by a U-boat while patrolling in advance of the convoy. She lay stopped as the convoy proceeded with its escort diminished by three smaller craft ordered to stand by the stricken cruiser.

The Germans learned of it and sent out three destroyers to finish her off. They found Edinburgh dead in the water with her turrets askew and her consorts circling nervously. As they closed in for the kill, Edinburgh’s turrets suddenly trained round and opened fire. The German command destroyer, Hans Schoemann, was hit by the first salvo and began to sink immediately. One of the others was badly damaged and had to be towed back to her base.

In the event, Edinburgh had to be abandoned and scuttled. The Admiralty now appealed to Prime Minister Churchill to call a halt to the PQ convoys until summer. They had lost two of their finest cruisers within a month and considered the North Cape runs “a millstone round our necks.” Churchill probably agreed, but the political pressure was too great. President Roosevelt and Premier Stalin were both clamoring for more convoys to be dispatched, and in the end they won out. Stalin even agreed to prior demands and started air raids on Luftwaffe fields in northern Norway. He also sent some destroyers to assist in escort duties and allowed the British to set up a command post north of Murmansk. The Admiralty’s advice went unheeded; Churchill ordered the PQ convoys resumed. He felt that “the operation is justified if half get through.”

Plans to Destroy the Entire Convoy to the Very Last Ship

The Admiralty did not agree but was bound to do as ordered. They decided, however, not to risk any more of their dwindling cruiser forces within the Luftwaffe air power circle or the Ice Devil operating area. The destroyers, corvettes, and trawlers would have to do the job alone.

PQ 16, dispatched on May 20, comprised 35 merchant vessels and the largest escort ever sent out. Five destroyers, four trawlers, four corvettes, and a minesweeper along with a CAM (Catapult Aircraft Merchantman), equipped with a Sea Hurricane fighter plane were to protect the convoy. They got their chance five days later as soon as they passed Bear Island when 30 torpedo planes and five dive-bombers attacked. So furious was the defense that this raid and over 220 more sorties flown over the next two days were beaten off with the loss of only six vessels. The Ice Devil U-boats got three more. A British cruiser force lay back out of sight but within easy call should heavy German surface units appear.

The German Naval Staff now decided that planes and U-boats could not do the job alone and that their surface units must join the action despite the critical fuel-oil shortage. (Aviation gas and diesel fuel were ample at that time.) Extra allocations were made so that all available forces could be sent against the next convoy, with the ultimate goal being the destruction of the entire convoy—“To the very last ship, including the escort vessels!” If this could be accomplished, it should stop the flow of supplies and materiel, regardless of political pressure. To add even further emphasis to the importance of the operation, it was given the ultimate badge: a code name. Henceforth, it would be known as Operation Rosselsprung (Knight’s Move).

When German Grand Admiral Raeder reported the plan to Hitler at his Berghoff headquarters, the Führer was not enthusiastic. He remembered the close call of Tirpitz in March and reminded Raeder of his standing order that heavy surface units should not sortie unless the whereabouts of enemy carriers was well established. Nor were they to engage equally powerful opposite numbers. The fact was, Hitler wanted to have his cake and eat it too. He always complained about the heavy surface units not pulling their weight for the resources they consumed while underway, but the restrictions he placed on them practically precluded their being used at all.

Beginning Operation Rosselsprung

Convoy PQ 17 departed Iceland on June 27. It comprised 34 freighters and tankers, six destroyers, two submarines, two antiaircraft vessels, and 11 tugs, trawlers, and sweepers. A covering force of two British and two American cruisers along with their destroyer screen was to hover just out of sight in much the same manner used for PQ 16, where they would be within easy call. Farther west was Admiral Sir John Tovey, Home Fleet Commander, with the battleships Duke of York and the brand-new USS Washington, along with three cruisers, the carrier Victorious, and their destroyer screen.

At the convoy conference held just before sailing, the merchant ship skippers had been impressed by “all that Navy brass,” and felt torn between feeling well protected and apprehensive about all the fuss.

While convoy PQ 17 was forming up, the brand- new Liberty ship Richard Bland ran aground and was damaged badly enough to force her return to port for repairs. Early next morning, in heavy fog, the convoy encountered heavy field ice and three more ships were damaged. One was forced to return and the other two were further slowed.

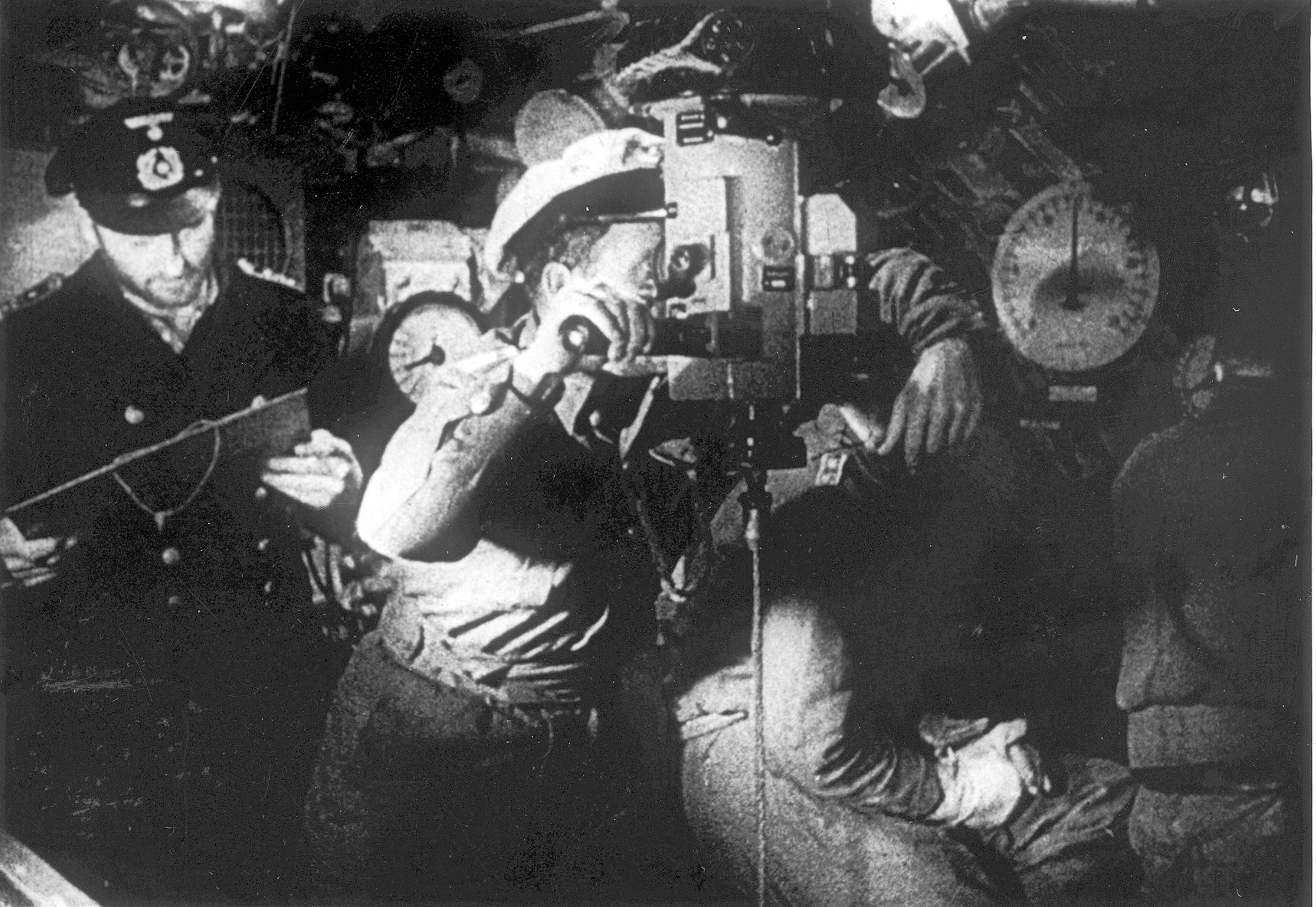

The bad weather prevented Luftwaffe patrols from detecting the convoy the first two days. The German Naval Staff suspected that it was at sea, however, because radio traffic around Iceland had petered out and had increased around the North Cape. Admiral Hubert Schmundt alerted his Ice Devil squadron of U-boats and had them form a picket line and dispatch two of their number out as scouts.

Confirmation came on July 1. U-456 made the first sighting. Then the first stages of Operation Rosselsprung were put into effect.

At Trondheim, the battleship Tirpitz and her cruiser consort Hipper were placed on three hours’ notice, as were both Scheer and Lutzow, which had just joined her at Narvik.

Next day (July 2), in late afternoon the weather cleared enough to allow the Luftwaffe to make its first attack on PQ 17. The U-boats that had been shadowing the convoy provided homing signals for nine Heinkel 115 torpedo float planes which appeared around 6:30. The Germans mounted a determined attack, but were beaten off by the concentrated fire of the entire convoy. The squadron commander’s plane was hardest hit and was forced down some distance ahead of the ships. As the escort vessels closed in on the downed bomber to finish it off, another of the Heinkels glided to a landing near the sinking bomber and scooped up the three German crewmen. Under the astonished gaze of the seamen, the float plane took off amid the geysers of shellfire and made good its escape. Grudging admiration for this feat of derring-do was coupled with satisfaction that convoy PQ 17 had come through it’s first test unscathed.

Later that day, the German heavy ships received their orders and made their way north toward Altenfjord. While negotiating the tricky entrance to the fjord, Lutzow ran aground, was extensively damaged, and had to be scheduled for repair. Several hours later, as Tirpitz and Hipper entered the sound, three of their guard destroyers, Galster, Riedel,, and Lody, also ran aground in the narrow channel and were damaged. The Germans had to adjust their plans to effect Rosselsprung without these four ships.

Radio Transmission From an Allied Traitor

Later that evening, RAF reconnaissance discovered that the heavy ship berths at Trondheim and Narvik were empty. The Admiralty then notified Admiral Sir John Tovey that Turpitz, Hipper, Scheer, and Lutzow were at sea. Accordingly, Tovey set a course for Bear Island, to put Home Fleet in a better position to cover the convoy against heavy surface attack. Rear Admiral L.H.K. Hamilton, commanding the cruiser covering force just out of sight to the north of the convoy, now swung south to get his ships into position.

Meanwhile, on the morning of July 3, PQ 17 had passed the Ice Devil picket line but the U-boats had been unable to mount an attack owing to bad visibility and the strong and alert escort. They were following along behind, several running low on fuel, and constantly reporting the convoy’s position.

In several radio rooms of the convoy, operators picked up a signal from the British traitor “Lord Haw Haw” broadcasting from Berlin. In it he promised the Americans in Convoy PQ 17 a lively fireworks display the next day, July 4, in celebration of their Independence Day.

About 2:30 am it looked as if the prediction would come true—aircraft were heard approaching the convoy. Although it was still daylight at this latitude, the heavy sea fog prevented most of the German planes from finding the ships. Finally one bomber flew beneath the overcast, located them, and delivered his attack. The torpedo passed between two vessels on the outside row and struck the lead ship in the next row, the Liberty ship Christopher Newport. Hit dead center, her machinery spaces flooded almost at once and she lay stopped. Her crew abandoned in two lifeboats and were picked up by the rescue tug Zamelek. The other German planes returned to their base without making an attack.

Convoy PQ 17 plodded on, now blooded by its first loss. At 8 in the morning, by pre-arrangement, all of the American merchant ships hauled down their ensigns, some tattered, some dirty and frayed, and replaced them with bright, spanking-new Stars and Stripes.

Decision Day for the German Admiral

For General Admiral Rolf Carls, head of the German Naval Group North at Kiel, it was decision day. He must know the whereabouts of the allied heavy ship forces, and in particular, the aircraft carriers. If the Luftwaffe could not locate them with certainty, he must at the very least be sure that they were not in the vicinity of the area in which he intended to operate his heavy surface ships. At around 1 pm, one of the U-boat scouts reported, in error, that Admiral Hamilton’s cruiser covering force contained one battleship, two cruisers, and three destroyers. Carls put Rosselsprung on hold.

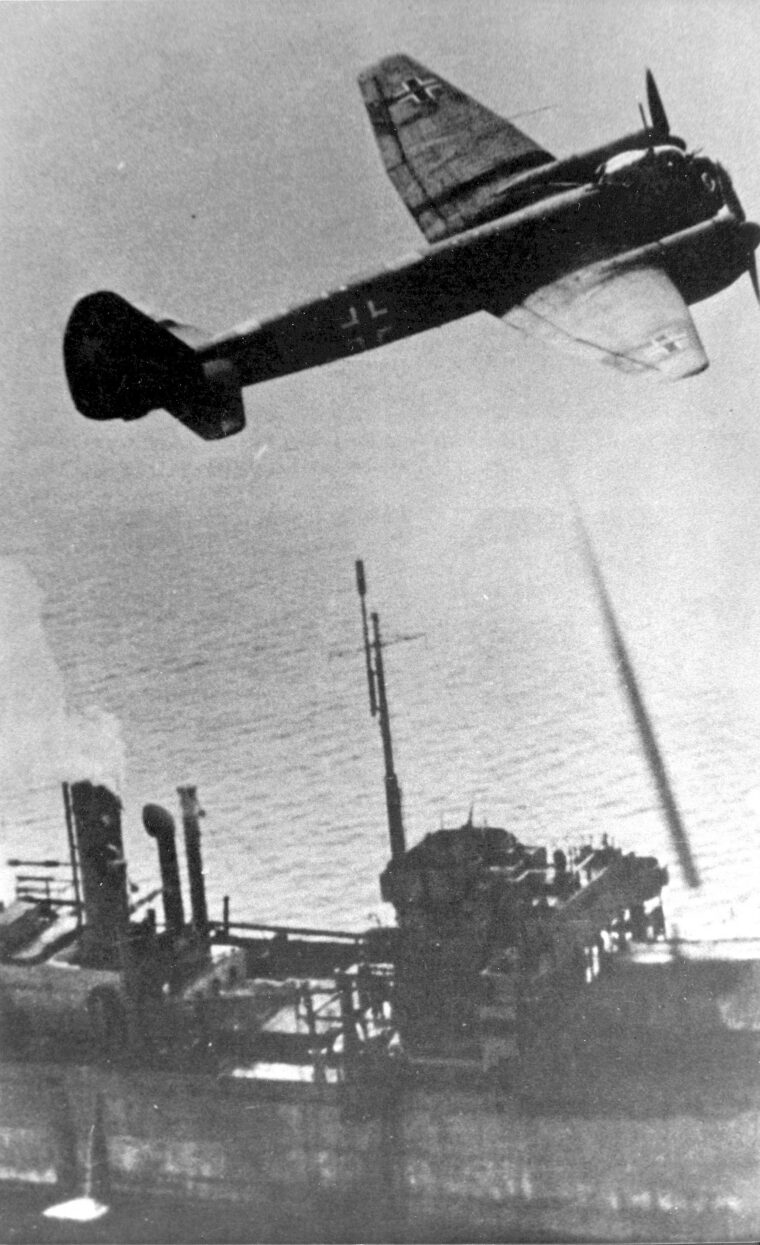

Because the Luftwaffe was under no such restrictions, Fifth Air Force Commander Colonel-General Hans-Jurgen Stumpff decided that he could wait no longer for the Navy to join in a coordinated strike. Further delay would put Convoy PQ 17 out of effective range altogether. Squadron 1 of KG 26 was alerted and briefed. Shortly after 6 pm they sortied with 23 Heinkel 111Ts (the T was the modified version of this twin-engined medium bomber and carried two naval torpedoes). Their attack was to be coordinated with Ju-88 dive-bombers, which were to draw the convoy’s gunners from the more vulnerable torpedo planes.

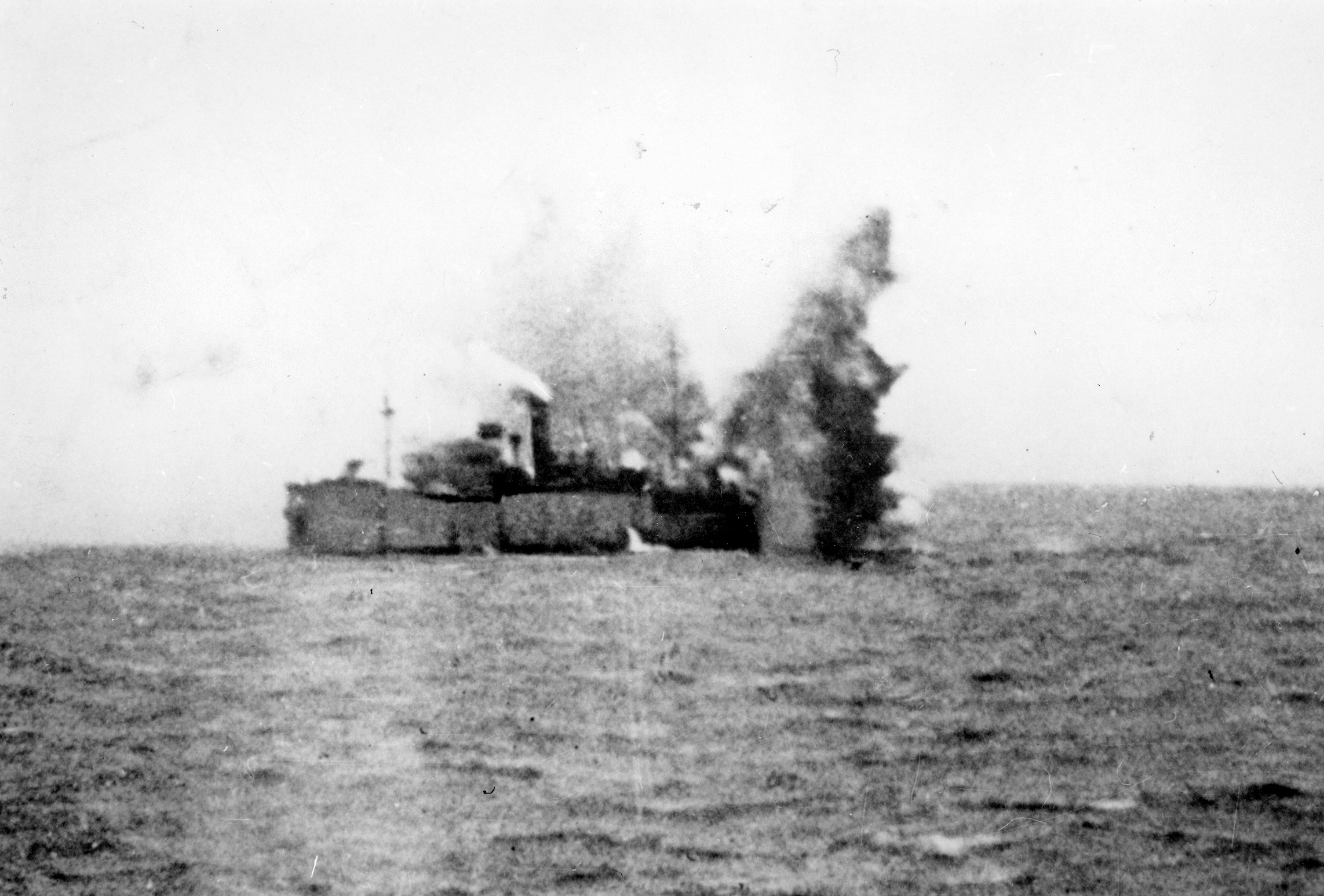

The German planes attacked at about 8 o’clock, although not exactly as planned. The Heinkels were late getting into position and the Ju-88s were given such a hot reception they could not complete their dives. By the time the Heinkels had formed for attack, all of the convoy’s guns were directed at them and only three completed their runs. Nevertheless the Germans made three hits: the American Liberty ship William Hooper, the British freighter Navarino, and the Soviet tanker Azerbaijan. As the convoy sailed past the three stricken ships, rescue tugs and minesweepers moved in to pick up the crews. Unknown to the convoy, two of the shadowing U-boats had also fired off torpedoes during the air raid, but all had missed.

During the next hour, the Azerbaijan signaled Commodore J.C.K. Dowding that her fires were under control, and that she was sufficiently repaired to make convoy speed. The three rescue vessels were now straining to catch up after hauling up survivors and finishing off the two freighters that were beyond salvage.

SECRET-MOST IMMEDIATE

Spirits were high after this latest action in which the convoy had come through well considering the forces arrayed against it. Then, shortly after 9, three bombshells of another type burst on the bridges of the command ships: signals from the Admiral.

The first arrived 9:11 pm. “SECRET-MOST IMMEDIATE. Cruiser force withdraw to westward at high speed.” Hamilton had been told two hours previous to expect further orders, but he had expected nothing like this.

Then at 9:23—another. “SECRET-IMMEDIATE. Owing to threat from surface ships convoy is to disperse and proceed to Russian ports.”

Before the shock of this could be digested or even discussed—another. “SECRET-MOST IMMEDIATE. My 21:23 of the 4h. Convoy is to SCATTER!”

To the commanders at sea, the startling messages, the sequence in which they were received, and their content could mean only one thing: The entire German High Seas Fleet must be just over the horizon. With misgivings, they went about putting the orders into effect, and the convoy of which they had all been so proud was soon nothing more than individual ships scattered as far as the eye could see.

Unknown to either the Admiralty at Whitehall or the commanders at sea, the German heavy ships were still at anchor at Altenfjord. Vice Admiral Otto Schienwind, commanding the fleet with his flag in Tirpitz, awaited orders from General-Admiral Carls of Naval Group North at Kiel, who in turn was waiting for authorization from Grand-Admiral Erich Raeder of the General Staff in Berlin. The entire chain of command suspected that no battleship was with the close covering force, and that the contact report was in error. Until this was confirmed, however, they dared not put operation Rosselsprung into effect.

In Whitehall, the indecision was almost as bad. Admiral Pound’s Intelligence Department could not state flatly that Tirpitz and Scheer were still at anchor. Nor could they state unequivocally that they were at sea, although they suspected not. Commander N.E. Denning, whose job it was to keep track of German surface units, told Admiral Pound that his operatives would probably not notify him if the ships remained in port, but surely would if they sailed or were preparing to sail.

Pound then returned to his office with his staff to render a decision. He listened to each officer’s opinion and then relaxed himself while he pondered a course of action. The German heavy ships could not be located with certainty. He would therefore assume the worst case—that they were either already at sea or would be shortly. He could see no good reason why they should not sortie—everything was apparently in their favor. In that event, the cruisers must be withdrawn because they would be heavily out-gunned. If Tirpitz encountered the convoy while it was still in formation, she could sink every one of them—it would be like shooting fish in a barrel. To Admiral Pound, his course was clear.

Two Vessels Sunk by the Ice Devils Before Breakfast

“The convoy is to be dispersed,” he announced as he wrote out the message and signed it.

Then he took it personally to the Communications Room and had it coded and transmitted. When he returned to his office, Admiral Moore had a thought. The message had said “dispersed,” which in the Mersig codebook meant to break formation and proceed at best speed to destination. This would leave the ships in more or less of a bunch, clearly not the admiral’s intention. Pound agreed.

“I meant them to scatter.”

In Mersig that meant to disperse fan-wise and proceed independently. He wrote out a correction to the former message and had it sent out straightaway.

Admiral Hamilton in the cruiser covering force ordered the destroyers in the escort to join him on his westward course and the balance of the warships to make best speed for Archangel. He had no instructions for the trawlers, tugs, and sweepers. They scattered along with the remaining merchant ships.

The U-boats and patrolling German aircraft could not believe what was happening. Nor could Admiral Schmundt. After receiving confirmation of the dispersal around 1 am on July 5, he ordered his U-boats to attack the lone ships as opportunities came. Before breakfast, two vessels had been sunk by the Ice Devils and the others were being hunted down.

When news arrived at Kiel that the Allied cruiser covering force was withdrawing westward, Admiral Carls put the heavy ships of Rosselsprung on one-hour notice. When the morning air patrols reported no Allied heavy ships in the operating area, Hitler’s approval was gained for the operation to proceed.

Admiral Schienwind, the German commander afloat, was already underway when authorization came to weigh anchor. By 2:30, Tirpitz, Hipper, and Scheer, along with their destroyer screen, were pounding northeast toward the scattered and helpless freighters. At the same time, the Luftwaffe’s Fifth Air Force flew off everything available to join in the attack.

At 5 in the afternoon the German heavy ships were reported by a Russian submarine on patrol off the North Cape and soon after by a British sub. Naval Group North at Kiel was now aware that their fleet had been discovered. An hour later, the Allies began jamming German wireless traffic. It was the first instance of this, and it convinced the General Staff in Berlin that the British Home Fleet heavy ships and carriers were being sent to cut off Schienwind’s return route. After an hour of hand-wringing, Grand Admiral Raeder canceled Rosselsprung. At around 10 pm Admiral Schienwind reluctantly reversed course and headed back to Norway.

153 Allied Seamen Killed, 150,000 Tons of Shipping Sunk

As it turned out, the battle fleet was not needed anyway. The Luftwaffe and the U-boats had a field day, hunting down and sinking the individual ships, now without any protection save their own guns. Fourteen were sunk the day after the scattering, and seven more over the next five days. Only 11 of the 35 merchant vessels made port, and 153 Allied seamen were killed. Also lost in addition to 150,000 tons of shipping, were nearly 3,300 trucks, 200 aircraft, 435 battle tanks, and 100,000 tons of other war supplies, ammunition, and foodstuffs, enough to equip an army of over 50,000 men. It was the largest single-day ship loss on the high seas for either side in World War II.

Although the news of this disaster was not revealed to the U.S. and British public until after the war, it became common knowledge among the seamen and the maritime community. An investigation was undertaken by the House of Commons, in which Admiral Pound admitted making the decision to scatter the convoy and also giving his reasons for it.

While the German heavy ships had not sortied until after the convoy had scattered, this was not known for certain until notes could be compared at war’s end. Even Pound’s critics admitted that the Allies had nothing in the area that could have stood up to the Tirpitz for very long. The Admiralty had, in fact, decided not to engage Tirpitz because the Home Fleet was low on fuel and was already heading for Scapa Flow when Tirpitz sortied.

Were the Allies Lucky to Have Not Lost More?

It is fortunate that the German General Staff also had bad information and withdrew the heavy ships before they could engage. Had Tirpitz and her consorts remained at sea, it is just possible that Rosselsprung’s objective may have been achieved, and that the 11 ships and their escorts that did survive might also have been destroyed.

The Russians were the most vocal critics and were scathing in their denunciation of Pound’s action. After all, it was their cargoes that were lost. Stalin began clamoring almost at once for more convoys to be dispatched, and President Roosevelt joined in. Vessels had been queuing up in Iceland since convoy PQ 17 had sailed, and now over 30 were waiting. Again the Admiralty was forced into action, but this time provided a “Jeep Carrierz” with the escort.

PQ 18 sailed on September 15 with 40 merchant ships. Ten were lost to Luftwaffe torpedo bombers and three more to U-boats. The PQ convoys were then canceled until mid-winter when darkness made the operation more feasible. When they resumed in December, they were designated J.W. in an attempt to negate the PQ stigma.

Admiral Hamilton had it right when he complained that the British War Office had neglected its Fleet Air Arm out of deference to the Royal Air Force. Any communication line operated without control of its airspace is foredoomed. History has borne him out.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments