By Colonel John P. Sinnott AUS (Ret.)

Seldom was the hand of fate so clearly exposed in the affairs of men as it did during the French and Indian War when Maj. Gen. Edward Braddock faced a military disaster before the gates of Fort Duquesne, today’s Pittsburgh. Braddock overcame daunting obstacles and handled his campaign “by the book” until the very end, that end being a massacre of his troops. The debacle was not supplanted in the American imagination for more than one hundred years, until George Custer fell at Little Big Horn.

Illustrative of destiny’s intervention is the contrast between the fates of British General Braddock and his Virginia Militia aide, Lt. Col. George Washington, on the banks of the Monongahela River during that terrible afternoon of July 9, 1755. Braddock died of a wound received in the battle; Washington, his clothing pierced by French and Indian bullets and with two horses shot out from under him, received not a scratch. Braddock’s name became synonymous with avoidable disaster while Washington emerged from the action with a hero’s stature.

Yet, Braddock and his men deserved a victory, if by no other means than their preparatory exertions. They hacked and blasted, with muscle and gunpowder, a 12-foot wide road through 110 miles of wilderness from Fort Cumberland (now Cumberland, Maryland) to today’s town of North Braddock, a Pittsburgh suburb. The road was completed, up to the site of the battle, between late May of 1755, when the first detachment of Braddock’s force left Fort Cumberland to hack out the road, and July 9, 1755, the day of battle.

Opposing Colonial Goals

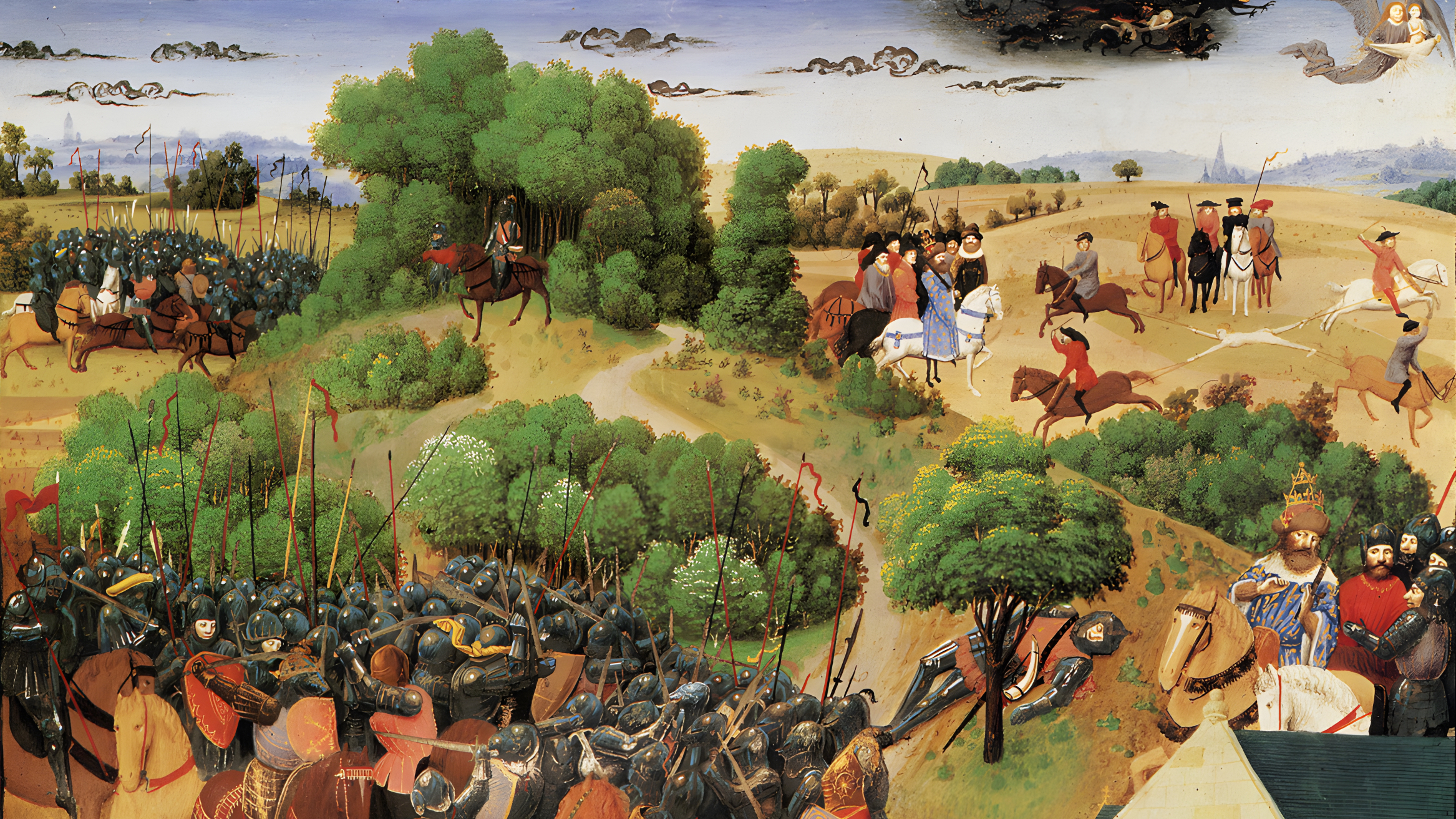

Very likely a substantial clash between the French and the British in North America was inevitable. Each had opposing colonial goals, and each wanted to control the continent. Owing to geography—generally the orientation of the lakes and rivers between the mouths of the Mississippi and the St. Lawrence, plus the run of the Appalachian Mountains paralleling the seacoast—the French had access to the heart of the continent and might use the mountains as a barrier to farther westward expansion by the British. By the 1750s, the French were exploiting this geographical advantage by means of a chain of settlements and forts that extended from New Orleans up the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys to Quebec.

The irreconcilable nature of the conflicting French and British colonial goals, the British expansion westward toward a line of French strongholds, and the French effort to prevent that expansion, created an issue of ethnic survival for the Indians. As a general matter, the French came to North America largely as missionaries, traders and trappers. Thus, the French were essentially visitors who lived among the Indians. The British, in contrast, came to supplant the Indians and repopulate a continent.

Thus the war, when it came, was made all the more savage because the Indians felt that only by eradicating the British could they have a chance to culturally survive. The French, being the lesser of the two evils to the Indians, drew the natives to their side who, in return, gave the French a major initial advantage over their European rivals.

The issue was finally joined in 1753, about two years before Braddock’s march. George Washington, then a 21-year-old major in the Virginia Militia, was detailed by Virginia’s Governor Robert Dinwiddie to deliver a letter demanding a French withdrawal from western Pennsylvania. The French at that time were expanding their control of that region eastward into the Appalachians, a migration that was in obvious conflict with British colonial objectives.

The French ignored Governor Dinwiddie’s order to vacate, compelling the governor in 1754 to organize an expedition of 180 troops under Washington’s command to support the small Virginian force building a redoubt at the site of present-day Pittsburgh, where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers join to form the Ohio River. This site, it might be noted, was selected by Washington.

In the course of executing this task, Washington, who had been promoted to lieutenant colonel, initiated a firefight with a French unit in the Pennsylvania wilderness on the morning of May 28, 1754, during which a French officer was killed. Thus, in one of history’s great ironies, George Washington’s skirmish in the Pennsylvania wilderness, near today’s Jumonville (named for the slain Frenchman), ignited the Seven Years War, or as it was known in British America, the French and Indian War. The consequences played themselves out over the next 45 years: first with the expulsion of the French from North America, then the expulsion of the British from North America south of Montreal, and even the French Revolution—all within George Washington’s lifetime.

Indian War.

A World War Begins

Following the May 28 fight, the French pursued Washington with a considerably larger force, compelling him to improvise a circular log palisade he called Fort Necessity. Soon besieged, weary, outnumbered and outgunned, Washington—for the only time in his life—signed an instrument of surrender. The French expelled the British force back toward eastern Virginia.

But the matter would not end there. A world war now had begun between France and England with the domination of the North American continent and the subcontinent of India as the goals. To prosecute the war the British needed a plan for their military operations in North America.

The Duke of Cumberland, as captain general of the British Army, approved a memorandum dated November 16, 1754 that committed two regiments of British regulars with artillery, supplemented by colonial militia, to break the part of the restraining cordon of French forts that extended from Nova Scotia to Fort Duquesne, the name given by the French to the redoubt at the fork of the Ohio River that they took from the Virginians and considerably strengthened.

Operations for 1755

To enable the British and colonial troops to take to the field as swiftly as possible in order to execute the plan, operations for 1755 were to begin first in the southern colonies, that is, Virginia, where it was believed the weather would be moderate. Fleet units of the Royal Navy deployed in the North American operation, moreover, were ordered to transport the two regiments with their equipment and stores from Cork, Ireland to Alexandria, Virginia and to further cooperate with Braddock’s force, as needed.

Braddock was to march westward through Maryland and Pennsylvania in accordance with the operation plan, reduce Fort Duquesne, after which he was to seize the French installations at Niagara and Crown Point in New York, near the southern end of Lake Champlain. This proposed campaign for the summer of 1755, although of large scope, was not unrealistic because Braddock’s augmented brigade of more than two thousand men was the largest European-style military force to assemble on the North American continent up to that time. Funds, moreover, were made available for the expedition and the colonial governments were ordered to provide the necessary horses, wagons and food supplies.

In its eventual composition, Braddock’s force included not only the 44th Regiment under Sir Peter Halkett and the 48th Regiment under Col. Thomas Dunbar, but also companies of Virginia Rangers and light horse with militia companies from New York, Maryland, and North and South Carolina. An artillery train was included, comprising a battery of no-less-than 29 field and siege guns from the Royal Regiment of Artillery. Also included in the British order of battle were 30 sailors from the fleet under a Lieutenant Spendelow (or Spendlowe) together with four midshipmen for handling the block and tackle needed to haul the artillery over the razor-back ridges that form the Allegheny Mountains.

Braddock’s efforts to attract Indians to this force, however, met with little success. Instead of a relatively large number of Indians for use in scouting, patrolling and screening, as proposed in the operation plan, only a few Indians stuck with him.

The colonies provided militia companies to reinforce Braddock’s brigade, but they failed—despite Braddock’s exertions—in their obligation to supply the horses and wagons that were essential to keeping such a large force in the field. Only through the direct intervention of Benjamin Franklin, who stretched his authority as Postmaster General, was Braddock equipped with marginally adequate supply transport. Rations, purchased from colonial contractors, were worse than a failure; a good portion of the provisions, for example, had to be condemned as unfit for consumption.

Nevertheless, Braddock was able to assemble the expeditionary force, with a minimally acceptable logistic support train at Fort Cumberland. The staff and line officers who accompanied Braddock in this campaign were particularly noteworthy. George Washington, for example, joined as an aide-de-camp to the general. Because he had traveled through the region several times, the last two times on military missions, Washington’s position on the staff was extremely important. Others under Braddock’s command were Sir John St. Clair, Braddock’s deputy quartermaster general; Captain Robert Orme, also an aide-de-camp and a personal friend of Washington; and Lt. Col. Thomas Gage (who, in 1775, became commander-in-chief of the British forces in North America). Daniel Boone also joined the expedition as a wagonmaster.

Most important for the march to Fort Duquesne, however, were the engineering officers who would choose the route and supervise construction of the road, the width of which was determined by the wagons and artillery. These officers were Patrick Mackellar, second ranking engineering officer in Braddock’s brigade and the senior engineer on the line of march; Harry Gordon, who was an engineer without a commission; and Lieutenant Adam Williamson.

Braddock’s Road

Braddock, in building this road from Cumberland, did not cut a trail through an entirely trackless wilderness. There was an earlier Indian path to the Ohio, named for a Delaware Chief, Nemacolin. A Virginia trading firm, the Ohio Company, in order to provide a route for company traders traveling to and from the Ohio River, had contracted with Cpt. Michael Cresap to improve this path through the wilderness, and it was generally over this trail that Washington traveled during his missions for Governor Dinwiddie in 1753 and 1754.

Nemacolin’s Path provided a route through the Allegheny Mountains, a barrier that is one of the most difficult obstacles to westward movement on the eastern seaboard. Seen from a few thousand feet in the air, the Alleghenies form a sequence of heavily wooded ridges that extend northwest-southeasterly through Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia. They were perpendicular to the British line of advance.

To cut and build a road 12 feet wide for 110 miles, generally following Nemacolin’s Path, in just a little more than one month using picks, shovels, saws, gunpowder, horses, oxen and human muscle, supported on a diet of rancid pickled pork and hardtack, certainly qualifies Braddock’s road as one of the great civil engineering achievements of the 18th century. Beyond question, this was a magnificent achievement, and tempts us to wonder if this task could be accomplished in the same time span today, with all of our modern technology.

To begin, a pioneer detachment set out from Fort Cumberland and Will’s Creek to Little Meadows, about 20 miles west. Expectation always exceeded performance in this campaign, and only two miles of the road were completed by the end of the first day. Because of the difficulty in building a road over Wills Mountain near Cumberland, Braddock personally surveyed the proposed route and decided to add an additional three hundred axmen to the job—until Royal Navy Lieutenant Spendelow found a pass through a valley at the foot of the mountain, enabling a good road to be built around Wills Mountain in less than two days.

As a general matter, Braddock’s engineers laid out the route in straight lines, except where the terrain required a deviation, for example, to reach a passable river ford.

Psychological Warfare

At the outset the French and their Indian allies made some effort to impede Braddock’s advance. For example, three British soldiers may have been killed by Indians near present-day Frostburg, Maryland, site of Braddock’s third encampment, and legend has it that they are buried at the campsite. Unfortunately for Braddock, this skirmish and the growing knowledge among the British troops of the brutal treatment awaiting soldiers captured by the Indians were not without a damaging psychological effect.

In this respect, the addition of colonial units to Braddock’s force may have been a mixed blessing. The colonials, it seems, reinforced and possibly embellished the terrors of Indian warfare in speaking with the British regulars. The brutality of the savages they faced was brought home most graphically not only through seeing the fate of the occasional straggler who fell into the hands of the Indians but also by means of the news of the massacre of two families near Fort Cumberland, the only survivor being a scalped child with two holes in his head. He died a week later in spite of the brigade surgeon’s best efforts.

Quite prophetically, the Duke of Cumberland specifically warned Braddock of the effect that this new form of warfare would have on his troops. The duke advised Braddock to cope with this likelihood in the following words:

“His Royal Highness does not doubt that officers and captains of the several companies will answer his expectations in forming and disciplining their respective troops. The most strict discipline is always necessary, but more particularly so in the service you are engaged in. Wherefore His Royal Highness recommends to you that it be constantly observed among the troops under your command, and to be particularly careful that they be not thrown into a panic by the Indians, with whom they are yet unacquainted, whom the French will certainly employ to frighten them.”

Braddock nevertheless failed to overcome this important morale problem. Possibly this deficiency may have had its basis in a disdain approaching contempt that he seems to have had for the troops in his command. There was, moreover, an officially countenanced lack of discipline among the troops during the march.

“Four Days in Getting Twelve Miles”

A great deal of urgency pressed the British forward. The accurate intelligence available to them indicated that Fort Duquesne was held by a small French force, but that a large reinforcement column of French troops, Canadian militia and Indian allies were on their way. Consequently, the British were eager to reach and reduce the fort before aid arrived.

As a result, the road-building progress seemed to Braddock and his staff agonizingly slow, a few miles being completed each day, in spite of the fact that judged objectively against the terrain in western Pennsylvania the rate of construction really was astonishing.

George Washington, for example, wrote:

“Instead of pushing on with vigor without regarding a little rough road, they were halting to level every mole-hill, and to erect bridges over every brook, by which means we were four days in getting twelve miles.”

To speed the advance, Washington proposed to Braddock that they hasten to Fort Duquesne with a smaller, lightly equipped and faster moving column. The slower moving train could follow in safety because the advance column would be between the train and the French. Eventually Braddock adopted Washington’s recommendation and selected 1,200 of his best men, most of the artillery, the naval complement, necessary stores and 51 supply wagons for his faster moving task force.

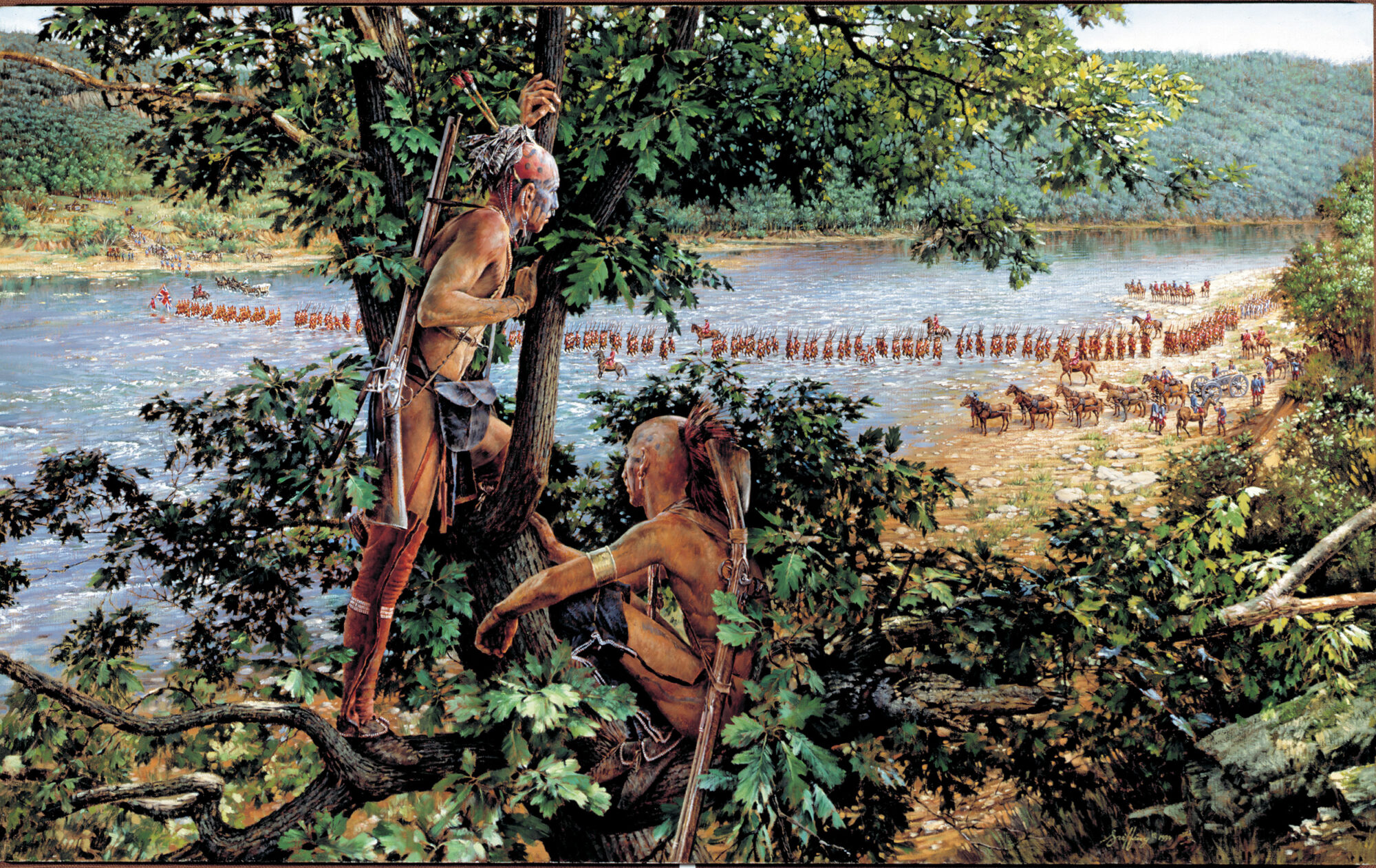

The task force moved on toward Fort Duquesne as swiftly as road construction permitted and stood on the banks of the Monongahela 20 days later. The French, perhaps in view of their numerical weakness, made no attempt to attack Braddock’s force while it was on the march, other than to keep it under close observation through their Indian allies. These Indian scouts naturally took advantage of opportunities as they occurred, taking eight or nine more scalps from the British in three weeks. Although these losses were considerably less than Braddock had anticipated, the conditions of these victims’ bodies must certainly have had a further unsettling effect on the British soldiers’ morale.

Another bit of bad luck took place during the march. Only eight Indians accompanied Braddock’s force. This small band was led by an Oneida sachem, Monakatooka. Monakatooka’s son, returning with a scouting party immediately after Braddock’s force had skirmished with some French-allied Indians, was shot and killed by “friendly” British fire. This loss, however, did not prevent Monakatooka and the six remaining members of his party from continuing on with Braddock.

In any event, the picked force eventually came within a few miles of Fort Duquesne. Still, steep ravines and ridges obstructed the approach. To Braddock, these topographical features were just more time-consuming obstacles. Accordingly, to avoid further loss of time, Braddock accepted a suggestion that the force camp at the present site of McKeesport during the night of July 8 and, early on the morning of July 9, ford the Monongahela River so as to reach the more easily traveled western side of the river at a place now known as Duquesne. Later in the morning, the Monongahela was to be forded once more just west of Turtle Creek in the present-day town of Braddock to enable the force to reach Fort Duquesne on the eastern bank of the river.

Forces Collide

Contrary to British expectations, the French did not contest either of these river crossings. This surprising inactivity on the part of the French seems to have fueled a degree of British overconfidence. The French, however, were not idle. A captain in the French garrison, Daniel-Hyacinthe-Marie Beaujeu, had been given command of a force of about 250 French and Canadian soldiers by the post commander, Cpt. Claude Pierre Pécaudy, sieur de Contrecoeur. Contrecoeur imposed the condition on Captain Beaujeu, however, that he must obtain support from their Indian allies before he could proceed with an attack on the British column.

Beaujeu, with 250 Frenchmen, seems to have shamed the 650 Indians—including Chief Pontiac—into joining him by threatening to attack without them. Around noon on July 9 Captain Beaujeu, stripped to the waist like an Indian, led his nine hundred men at a run toward Braddock’s second Monongahela crossing west of Turtle Creek. Between 1:00 and 2:30 pm, the two forces collided in the field.

Although Braddock’s rear guard had just completed its crossing, the whole British force was strung out over a little less than a mile on a forest trail (between the mouth of Turtle Creek and today’s Sixth Street in North Braddock). The path was flanked on both sides by ravines and at the middle and to the right of the British line by a commanding hill, unoccupied by either side at the time the engagement began.

The battle began not as an ambush, but as a meeting engagement in which the French, believing that Braddock was still at the second crossing, were as stunned to find the British so far advanced along the trail as the British guides and vanguard were stunned to meet any French at all.

Captain Beaujeu fell in the first exchange of fire between the British vanguard and the French party, but not before he ordered his force to run down the ravines that flanked both sides of the British line of march. The French command passed to Cpt. Jean Daniel Dumas who held command throughout the balance of the engagement.

In spite of the mutual surprise and the loss of the French commander, the war whoops of the Indians and their crossfire from concealment, combined with a muddle in the British line as the advance guard and pioneers fell back on the troops rushing forward in support, combined to give the initiative in the action to the French and Indians. Consequently, the French occupied the hill on the right flank of the British force early in the battle. By this time, however, the British formation could not be called a line; the men were huddling together in clumps, firing at random and frequently shooting their own comrades in the backs.

The militia companies, more familiar with Indian warfare than the British regulars, appear to have suffered severely from this “friendly fire” because they moved off the road, taking cover in the brush. They thus placed themselves between the enemy and the regulars who remained on the road.

Although the British and colonial officers attempted gallantly to rally the troops, they could not establish a coordinated and effective defense. Moreover, despite timely recommendations from his staff, it took Braddock a long time—as time is counted in engagements of this character—to recognize the tactical importance of the hill on his right flank. Unfortunately for the British, their troops’ morale had so deteriorated by the time Braddock ordered the hill to be taken that they could not be led by the surviving officers to assault the hill effectively.

The terrible crossfire continued from the front, the hill and the ravines to the front and both sides of the British force, a crossfire from an enemy that could not readily be seen.

“Sheep Pursued by Dogs”

Through the years Braddock’s decision to split his force has been criticized. The combined force, it has been argued, would have made a better stand against the French and Indians when the battle was joined. But in view of the fact that the British light column enjoyed a significant initial numerical superiority in the battle and that the unit left behind under the command of Colonel Dunbar was largely a supply train with additional pieces of artillery and troops not considered to be of the best caliber, it is difficult to understand how the addition of Colonel Dunbar’s unit could have changed the outcome of the battle beyond making the loss even greater.

More to the point is Braddock’s failing with respect to morale and discipline. Braddock’s inadequacy in addressing these problems probably gave victory to his opponents. It is clear, for instance, that during battle the British soldiers were generally terrified into inaction by the Indians’ frightening style of fighting and were incapable at a critical point in the engagement of following the orders they were given.

In the course of the battle, Braddock was seriously wounded by a round that entered his right arm and lodged in his lungs. This left the force essentially leaderless, the battle being continued by the British through the individual initiatives of the remaining officers and the degree to which these officers were able to influence the actions of the enlisted men in their respective immediate vicinities.

The young Washington fought gallantly, if horrified at what he was seeing. Two horses were shot out from under him. His coat and hat were pierced by bullets, but—as would be true to the end of his life—he was never wounded.

Eventually, after several hours of firing, the teamsters cut their horses loose from the wagons, mounted the dray horses and rode off. This caused a general panic among many of the soldiers who then ran back to the Monongahela River crossing. They ran, as Washington put it, “as sheep pursued by dogs.”

With all hope of resistance gone, Washington placed the wounded Braddock on a cart and, with some troops who remained under discipline, carried the general back across the Monongahela. A defensive position on the west bank of the river was swiftly abandoned as the troops slipped away from their assigned posts, thus continuing the general rout. All that remained, all that could be done, was to organize the rout into a retreat, in order to withdraw at least as far to the rear as Colonel Dunbar’s unit.

Death of a Major General

On the morning of the 10th, Washington reached Colonel Dunbar’s detachment, and by July 12, the final few wounded and stragglers joined the other survivors with Colonel Dunbar. Braddock, still in command, ordered the retreat to continue on July 13, leaving the destruction of most of the supplies, wagons and stores to be accomplished by the rear guard.

Braddock died on the evening of July 13 and was buried on the morning of July 14 in the road near the head of the column. The grave site was chosen so that the wagons, horses and troops marching over it would obliterate all indication of the place of the general’s interment to prevent the French and Indians from desecrating his grave.

Later, in the 19th century during some road repair work, workmen found a skeleton and insignia indicative of a high-ranking officer. The remains, assumed to be Braddock’s, were removed and reintered in a small knoll near his road. The grave is marked today by a monument on U.S. 40 between Farmington and Chalk Hill, Pennsylvania.

Savagery of the Victors

The losses sustained by the two sides were utterly disproportionate. The British suffered 456 killed (including two midshipmen) and 520 wounded from a total of 1,469 engaged, or 66 percent casualties. The French sustained 23 deaths and 16 wounded from an engaged combined force of about nine hundred French, Canadians, and Indians, or 8 percent casualties.

Ordinarily, a victory such as this, against the odds and with stunning results when defeat seemed inevitable, would have added much to the military glory of France. That it did not owes much to the savagery of the victors. The French and Indians pursued the retreating British only as far as the Monongahela River. Scalping both the dead and the wounded who were left behind was only to be expected from the Indians in the heat and intoxication of battle, although the French appear to have tried to stop the Indians from scalping the wounded during the pursuit.

What cannot be condoned, or even explained, is the Indians’ treatment of the British prisoners that a French captain named Contrecoeur permitted on the evening of July 9. Contrecoeur allowed about a dozen British prisoners to be stripped, tortured with firebrands and red-hot irons, and finally burned to death at the stake on the banks of the Allegheny River opposite the fort.

Aftermath of Fort Duquesne Battle

The French victory at Fort Duquesne had several notable consequences. The immediate result was a general uprising among the Indians, the burden of which was borne largely by British settlers in and west of the Allegheny Mountains. French prestige also was greatly increased among the Indians, causing more Indians to join the French cause. And, most certainly, the disaster turned the Duke of Cumberland’s carefully developed operational plan for 1755 into ashes.

But the British, indeed, lived up to their bulldog reputation. They persevered through other remarkable disasters until their effort eventually culminated several years later in the victory of Wolfe over Montcalm at Quebec, a victory that gave North America to Great Britain.

We can also reassess the ultimate effect of the French and Indian War from another standpoint. All too often this war is dismissed with the cliché, “We speak English today because the British won the French and Indian War.” On reflection, it must be acknowledged that quite a bit more was at hazard than the mere issue of language. Considering the fundamental difference between French and British colonization philosophies, how can we doubt that the missionary/trader approach of the French, as opposed to the Indian-supplanting British settler, would have resulted in a markedly different development for North America than that which it enjoys today?

The American and French revolutions, moreover, can also be looked upon as the manner in which unsettled issues arising from the French and Indian were finally resolved. Thus, the taxes imposed on the colonies to help pay for the war led directly to the American Revolution with its rallying cry of “Taxation without representation is tyranny.” With respect to the French, support for the American colonists against the British found some basis in a desire for revenge, or at least in a wish to recoup the losses that France sustained in the more general Seven Years War.

This support for the American colonists and their antimonarchical Declaration of Independence went a long way toward bankrupting the Bourbon monarchy. Apart from the revolutionary philosophical concepts expressed in the Declaration of Independence, the monarchy’s need for money led to oppressive taxation, a major contributor to the French Revolution. Sooner or later a French Revolution probably would have occurred. But the form of that revolution and its consequences for the course of European history, (the Reign of Terror and Napoleon) might have been considerably different if France’s transition from monarchy to republic had been a more gradual development.

Although the French and Indian War involved numerically small forces—even by the standards of the 18th century—this terrible struggle fought out in the grime, sweat and deprivation of a trackless wilderness was a profound historical event that shaped our world into what it is today.

Another result of the battle: The young George Washington, for all his admiration of the British army and officer corps, could readily see that its redcoated soldiers, even if so formidable on an open field in Europe, could be defeated by North Americans using new tactics. It was a lesson he would apply with telling effect 20 years hence.

In a final defense of Braddock, however, it must be said that his efforts did not end in a terrible waste. His road to the Ohio River became a primary route through which settlers from the east reached the fertility and riches of the Midwest, thereby populating and developing Ohio, Indiana, Michigan and Illinois. About 50 years after the great disaster on the Monongahela, in order to further promote settling the Midwest, Congress financed the first National Road, a byway that generally followed Braddock’s route and that eventually became, and still is, U.S. 40. Considered in the long term, although Braddock and his magnificent force met only with tragedy and defeat, he and his engineers built for a greater purpose than they ever could have imagined: they built the gateway to a continent.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments