By Robert F. Dorr

A man who was close to Adolf Hitler and hardly impartial later saidthat the Führer had “a mood of merriment” for a brief period that day.

It was Friday, November 26, 1943. A carefully arranged collection of the Third Reich’s most advanced weapons stood ready—almost—to be demonstrated to Hitler. The location was the German military airfield at Insterburg in East Prussia.

Traveling to Insterburg from Berlin with his leader aboard a Junkers Ju-52 tri-motor transport plane, Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring hoped his orders to set up an impressive display had been followed to the letter.

Göring was in disfavor with the Führer even though the German air force, the Luftwaffe, of which he was in charge, was shooting down American bombers right and left. A month ago, during one mission, Luftwaffe pilots had shot down 60 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses, each with a 10-man crew. Göring kept telling the Führer that the Americans would not be able to continue to lose bomber crews at this rate, that the Allies would never be able to launch an invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe because German fighter pilots commanded the sky. Hitler heard this, was encouraged by it, but saw Göring, grotesquely overweight and addicted to morphine, as an asset of declining value. The Führer ardently hoped that he would ensure that Germany’s battle-hardened airmen would continue to command the skies despite the growing strength of the U.S. Eighth Air Force.

Göring saw this as his day to shine. Göring looked “like a child with a new toy,” one observer commented, as he prepared to claim credit for Germany’s recent scientific advances. The Führer was especially interested in a new jet aircraft called the Messerschmitt Me-262, the reason for his “merriment.” Today Göring would be certain the Me-262 was showcased to good advantage. This was his chance, he believed, to restore his on-again, off-again status in good standing with the Führer. It was also a grand opportunity to outshine his rival, Field Marshal Erhard Milch, who held the title of Air Inspector General.

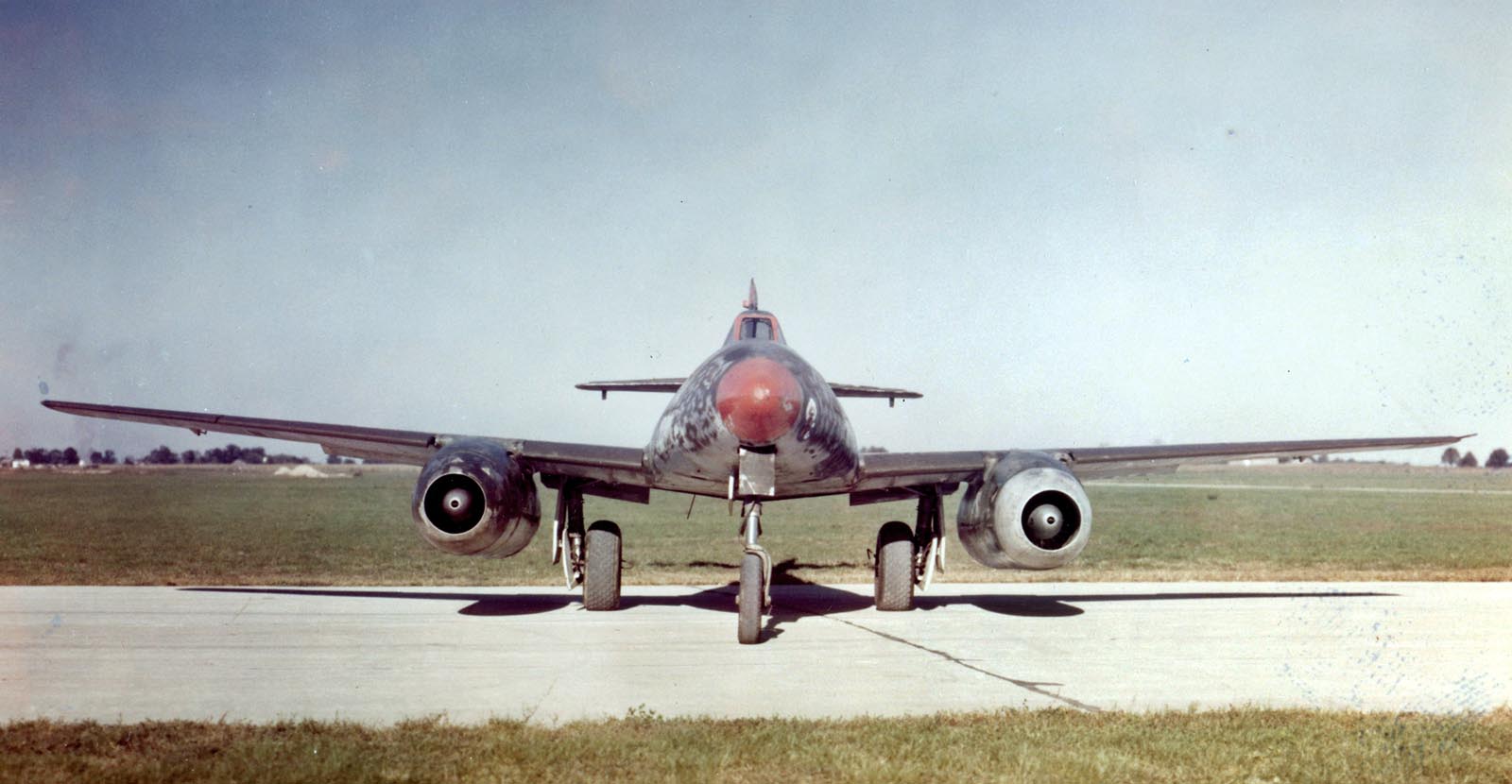

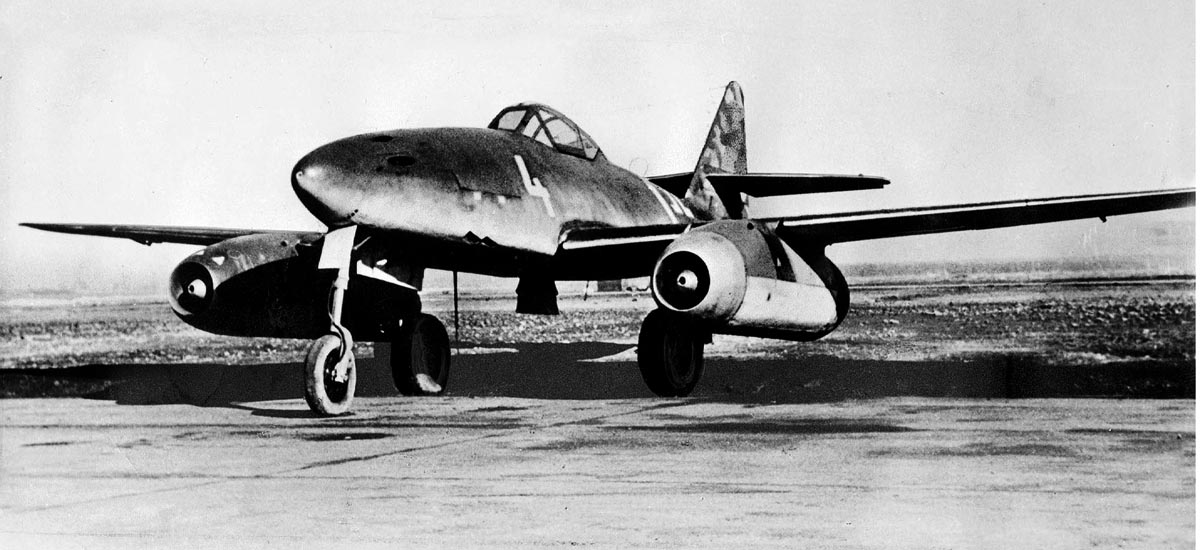

Several “black,” or secret, aircraft and items of equipment were ready for Hitler’s inspection. None looked more deadly basking in the winter sun than the Messerschmitt Me-262 Schwalbe (Swallow), the wunderwaffen,or “wonder weapon,” that was soon to become the world’s first operational jet fighter. Although he was his country’s highest ranking military officer, wearing an elaborate uniform of his own design dripping with awards and decorations, Göring was not as well informed about the Me-262 as he thought.

This was soon to be apparent as the Ju-52 landed at Insterburg just past noon, taxied to a halt in front of the top brass at the military airbase, and disgorged its very important passengers. Emerging from the transport were Hitler, Reich Minister of Armaments Albert Speer, Göring, Milch, and an entourage of officers of the Luftwaffe. Hitler’s personal pilot, SS Major General Hans Baur, said that he flew from Berlin, taking off from Tempelhof airport and making the short flight in good weather, so there was no problem in having the transport plane overloaded with so many notable persons.

Hitler, it should be noted, did not like flying on a crowded plane and always kept a seat for himself and his painting of Frederick the Great in a case. He did not talk during flights, since flying scared him. Baur’s recollection notwithstanding, some of the other luminaries may have traveled from Berlin aboard other airplanes.

Waiting to greet them on arrival was Germany’s most important aircraft designer, Professor Willy Messerschmitt. The tall, thin, balding Messerschmitt wore his title handily even though he possessed no academic degree. He had made certain his name was indelibly attached to the new Me-262 jet, even though he had not worked on the engineering team that designed it. In fact, Professor Messerschmitt had had almost nothing to do with the plane, a Messerschmitt that was going to ensure the Reich’s deliverance.

Other aircraft and weapons were ready and on display around the airfield. Pilots were preparing to fly in a demonstration for the Führer. It would not be an exaggeration to say that every man on the airfield on that bright November day was looking to ingratiate himself with the leader and chancellor of the Reich.

Adolf Hitler was 54 years of age. He was five feet, eight or nine inches in height with a manner that often seemed unfeeling or callous, a likely defense against his discomfort with virtually every other human being in his circle. He began the afternoon at Insterburg in the subdued and businesslike way that was often his manner while his temper was in check. No photograph appears to have survived of his visit to Insterburg, but it seems certain he was wearing a peaked cap and his gray winter military overcoat without the swastika armband. He had rarely worn the coat since the war began.

There is every reason to believe that the Führer was here only because of his interest in the Me-262; the other weapons were of little or no interest to him. Göring had asked Milch to organize the display and did not include the He-280 jet among the exhibits because Milch himself had struck the Heinkel from the development list in favor of the Me-262 eight months earlier. Göring had “nationalized” the Heinkel airplane company and detained Ernst Heinkel, who would not be fully rehabilitated until the postwar era, and had also seized the Arado company, maker of the Ar-234 jet bomber, after its chief, Heinrich Lübbe, refused to join the Nazi Party. It was up to Willi Messerschmitt, the perfect sycophant, to surpass the Reich’s other planemakers by putting on a good show for the Führer.

Hitler was initially curious and inquisitive when Willi Messerschmitt and others began showing him around, but he soon began to appear impatient. Hitler may not have been that interested in the V-1 robot bomb, two anti-shipping missiles called the Hs-293 and Fritz-X, and film of the new panoramic radar sets and the Korfu receiver stations tracking British bombers by their radar emissions during a night attack on Berlin a few days earlier.

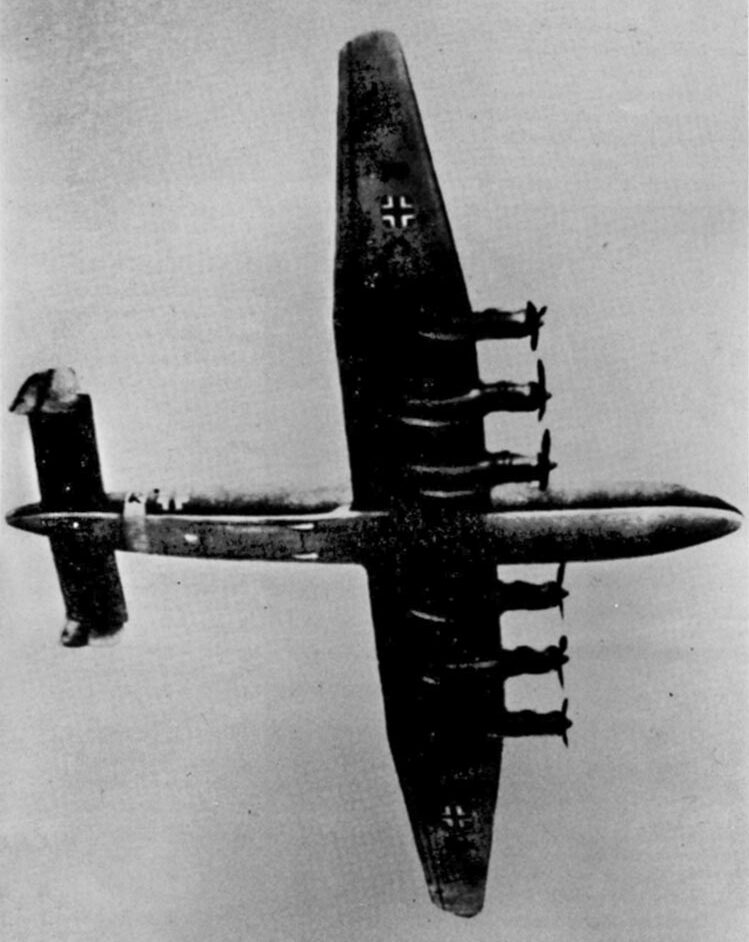

A six-engined Junkers Ju-390, the largest land plane ever built in Germany, was on display and was mostly ignored. Baur later said that it clearly involved developmental and operational costs that were unrealistic.

A four-engined Junkers Ju-290A-5 (werke no. 0170, marked KR+LA), an early version of a big plane that could be used as a transport or a bomber, was part of the display. Bauer later wrote in a German-language memoir, “ For my needs, the Ju-290 was especially suitable. I was just then inside the aircraft and was taking a good look around when Hitler stuck his head in the door. I called to him and asked him to come inside. Hitler noticed immediately the advantage of this ‘Pullman Wagon’ with which without difficulty up to 50 people could be flown around. In addition, the aircraft was excellently armed with 10 super-heavy machine guns.”

Hitler said, “I want one for my personal use.” It would happen a year later when a similar Ju-290A-7 was assigned to his personal flight unit as a Führermaschine—although Hitler would never fly in it.

The Ju-290 in which Hitler never flew had a special passenger compartment in the front of the aircraft for the Führer, which was protected by a half-inch (12mm) of armor plate and two-inch (50mm) bulletproof glass. A special escape hatch was fitted in the floor, and a parachute was built into Hitler’s seat; in an emergency it was intended that he would put on the parachute, pull a lever to open the hatch, and roll out through the opening. This arrangement was tested using life-size mannequins. The escape seat for the Führer has appeared several times in speculative fiction.

Hitler never assigned a high priority to large aircraft and seemed to have no further interest in this one. The Third Reich would reach the end of the war without ever having any significant number of four-engined bombers, while the United States and Britain would employ more than 60,000. At this juncture in the war, those Allied four-engined bombers were nothing more and nothing less than fat, inviting targets for German fighters, and Hitler had no reason to think that would change.

Eager to increase Hitler’s interest and to upstage Milch, Göring attempted to take the Führer’s arm. Hitler shook off the gesture but could not prevent Göring from acting as chief guide, speaking loudly, claiming credit for many of the technical achievements for his own staff. Göring talked while Milch looked on, infuriated and embarrassed.

In the book The Rise and Fall of the Luftwaffe, David Irving described the debacle that followed. The Reichsmarschall “took the printed program out of Milch’s hands [Irving wrote] and began introducing each aircraft to Hitler, working his finger down the list. He was unaware that one of the fighter prototypes had had a mishap at Rechlin [the German flight test base on the south shore of the Müritzsee] and as a result one aircraft was missing; the remaining aircraft had each been moved along one place in the line. Milch saw what was going to happen and took his revenge: he stepped tactfully back into the second row. Where the missing fighter should have been, there was now a medium bomber. Göring announced it to Hitler as the single-seater; for several more exhibits this farce continued until the Führer decided that enough was enough and pointed out Göring’s error.”

The star of the show was the Me-262 jet fighter, but the Insterburg exhibit also included an Arado Ar-234 twin-jet reconnaissance aircraft and bomber, which was transported to the event with great difficulty. While the Me-262 was at the event to show its flying skills, the third airframe in the Arado jet series, the Ar-234V3, was dismantled and transported by road to Insterburg, where technicians hurriedly pieced it back together for static display. The Arado was parked unceremoniously between a pair of Junkers Ju-88 twin-prop warplanes, one of which carried special equipment for laying smoke screens.

According to Arado company records, Hitler immediately gave the planemaker Arado—now nationalized—carte blanche to obtain factory personnel, raw materials, and funds so that the company could build 200 Ar-234s by the end of 1944. Some former members of Luftwaffe bomber units, who had been scheduled for reassignment as ground troops, possibly to the horrors of the Soviet front, were diverted to Arado to become workers on the project.

It did not help that an Me-262 took off as part of the demonstration, flamed out, and had to limp back to the runway for a dead-stick landing with pilot Fritz Wendel at the controls. Hitler appeared impatient as a second Me-262, with Gerd Lindner in the cockpit, took off with its imperfect Jumo 004 turbojet engines howling, circled over the visitors, and flew overhead with no apparent flaw. This was the moment when Hitler’s face changed and his eyes brightened.

One member of Hitler’s coterie who knew nothing about aviation, Hitler Youth leader Artur Axmann, later wrote of a “sparkle” in the Führer’s eyes.

Hitler had had a question in mind ever since he learned about the new weapons. Now, he posed the question not to Göring but to the ever servile Messerschmitt. The pair walked side by side. “Tell me,” Hitler said. “Is this aircraft able to carry bombs?”

Messerschmitt was clearly uncomfortable and seems to have improvised with his quick answer. “Yes, my Führer. It can carry for sure a 250-kilogram bomb, perhaps two of them.”

No one involved in the design of the Me-262 had ever considered such a thing.

“Well!” Hitler beamed. “Nobody ever thought of this!” He was certainly right on that point. “This is the Blitz bomber I have been requesting for years.” Another listener heard Hitler used the word Schnellbomber,or fast bomber, a concept that had been on his mind for some time.

It was the right moment for Messerschmitt to say, “This aircraft is a fighter my Führer. It has the potential to reinforce our command of the air over the Reich.”

But Messerschmitt said nothing.

“No one thought of this,” the Führer repeated. “I’m going to order that this 262 be used exclusively as a Blitz bomber, and you, Messerschmitt, have to make all the necessary preparations to make this feasible.”

Watching this exchange, Maj. Gen. Adolf Galland, one of the Reich’s most experienced combat pilots, felt his heart sink. Galland had met Hitler previously and knew the Führer wanted a Blitz bomber that would halt an invasion by the Western Allies. Willi Messerschmitt, who knew less about the aircraft bearing his name than Hitler realized, was making it sound all too easy. Converting the Me-262 into a bomber required structural changes, a relocation of its center of gravity, and new internal wiring. It was not easy, but it was also not quite so much a challenge as the engines. Messerschmitt’s engineering team already knew and had demonstrated that day that the Jumo 004 turbojet was cantankerous and unreliable. The fixes were going to take longer than anyone imagined.

Very likely the highest ranking 31-year-old officer in any military branch in the world, the tough-minded and often argumentative Galland was approaching the end of a prolonged period when he believed the Luftwaffe could prevail and Germany could win the war. The previous month’s Luftwaffe triumph at Schweinfurt had been a devastating blow to the Eighth Air Force, to the daylight bombing campaign, and to Allied hopes for an invasion to liberate Nazi-occupied Europe.

With that recent success in mind and with wonder weapons arrayed all around him and Adolf Hitler talking of support for the military, Adolf Galland should have been riding high and thinking big. Although he was relatively young, Galland was, like many of his peers, very tired. As long ago as the Battle of Britain more than three years earlier, the Luftwaffe had sustained enormous losses. Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union two years earlier, although easy at first, became a meat grinder. The sheer number of aircraft the Russians kept throwing at them was beginning to wipe away some of the Luftwaffe’s best.

This very month, November 1943, the Americans were beginning to field a new fighter that they had not planned for, had not wanted at first, and did not yet quite know how to use. The North American P-51 Mustang was not a wonder weapon, but it was an accidental triumph of engineering. Galland watched the Insterburg display, saw the Führer’s smile, and was quietly grim.

Gifted with a more cheerful personality was Hans Baur, the air ace from the Great War who was Hitler’s personal pilot. A lifelong aircraft fanatic, Baur was savoring the display of new flying machines.

“Baur was a decent person in many ways,” said his biographer, G.G. Sweeting, in an interview for this article. “He was a good husband and loyal family man with a pleasant disposition, but he never wavered in his stalwart support for National Socialism and for Hitler. He was busy running his private squadron, which was not a part of the Luftwaffe. He told me he was really impressed by the jets, especially the Me-262, but also by the Ju 290A-5 transport.”

Baur’s outfit was dubbed Die Fliegerstaffel des Führers, or the Führer’s personal squadron, and was marked with a special insignia that was painted on the nose of all planes, a black eagle head on a white background, surrounded by a narrow red ring. Unlike Galland, Baur was still optimistic about the war. He pictured himself squiring Hitler about in the transport in a sky made safe by the shark-like, jet-propelled Me-262s.

In The Me-262 Stormbird,authors Colin D. Heaton and Anne-Marie Louis recount what Baur told them. “Hitler was always excited about new things, like a child at Christmas, you could say. If there were any new ideas in tank, U-boat, or aircraft designs, he wanted to see all the blueprints and have them explained to him. His memory was photographic and he forgot nothing.”

As the event at Insterburg drew to a close, Hitler returned with Baur and Axmann to the Ju-52 for the flight back to Berlin. Before turning to the plane, Hitler chatted with Speer on possible production figures, and Speer told him that he would have to research that. Hitler told him to make it quick and appointed Speer as overseer on the Me-262 project.

In the meeting, Göring expressed support for the Me-262 and named some prominent German pilots who might conduct test flying of the revolutionary jet. Speer pointed out that the Reich was facing a shortage of raw materials for war projects. There was a particular concern about the supply of nickel, needed in jet engines. It would probably not have occurred to Speer to mention the American daylight bombing campaign, which, so far, was achieving little in its own efforts to stymie aircraft production. Hitler told Speer that he would have a letter prepared authorizing procurement of whatever was needed to acquire the materials. Speer concurred.

As Bauer recalled, “I then remembered that the next day Hitler called his secretary, Fraulein [Traudl] Junge, into his study where he composed the letter. Later Speer came by, picked up the letter, gave the party salute and left. The funny thing was that later that day some gauleiter [district leader] from somewhere had called, demanding to speak with the Führer. Well, Bormann took the call and I remember him telling the man on the other end of the line to just ‘shut his mouth and give Herr Professor Speer whatever the hell he wanted,’ and his life would be much easier. ‘Bothering the Führer with this complaint would not be advised.’ And then he hung up the phone.”

In a Monday, December 20, 1943, speech to Wehrmacht officers, Hitler revealed the priority he placed on the Me-262 as an anti-invasion weapon: “Every month that passes makes it more and more probable that we will get at least one group of jet aircraft. The important thing is that they [the enemy] get some bombs on top of them just as they try to invade. That will force them to take cover, and in this way they will waste hour after hour! But after half a day our reserves will already be on their way. So if we can pin them down on the beaches for just six or eight hours, you can see what that will mean to us.”

This was the speech in which Hitler predicted an Allied invasion two or three months hence, much sooner than it actually happened. This was also the date of a letter in which President Franklin D. Roosevelt agreed with Prime Minister Winston Churchill that an announcement could be made at the first of the year that General Dwight D. Eisenhower would command Operation Overlord, the code name of the invasion for which the Führer was preparing.

Hitler’s fixation on using the Me-262 to carry bombs may have delayed the jet’s entering service, but technical glitches with its jet engines were probably equally responsible. Galland believed that if the Me-262 could have been gotten into battle a year earlier (its first combat mission was on July 25, 1944), it would have swept the skies of Allied bombers and forced a postponement of Overlord. But was a single conversation with Willi Messerschmitt at the big weapons display the reason the Me-262 did not arrive sooner? It was not.

There were other repercussions after the big weapons display for the Führer at Insterburg. One was a difficult experience for unrepentant Nazi and personal pilot Hans Baur. Sixteen months later, one of Baur’s last wartime acts was to fly the Ju-290 intended for Hitler’s use to Munich-Riem airport on March 24, 1945. Baur parked the aircraft in a hangar and went to his home. The next morning, he learned that Allied bombing had destroyed the magnificent four-engined transport and its hangar.

The Third Reich soon suffered a similar fate, despite the wonder weapons that so infatuated Adolf Hitler during his big weapons display.

The merriment was over.

Join The Conversation

Comments