By Mike Phifer

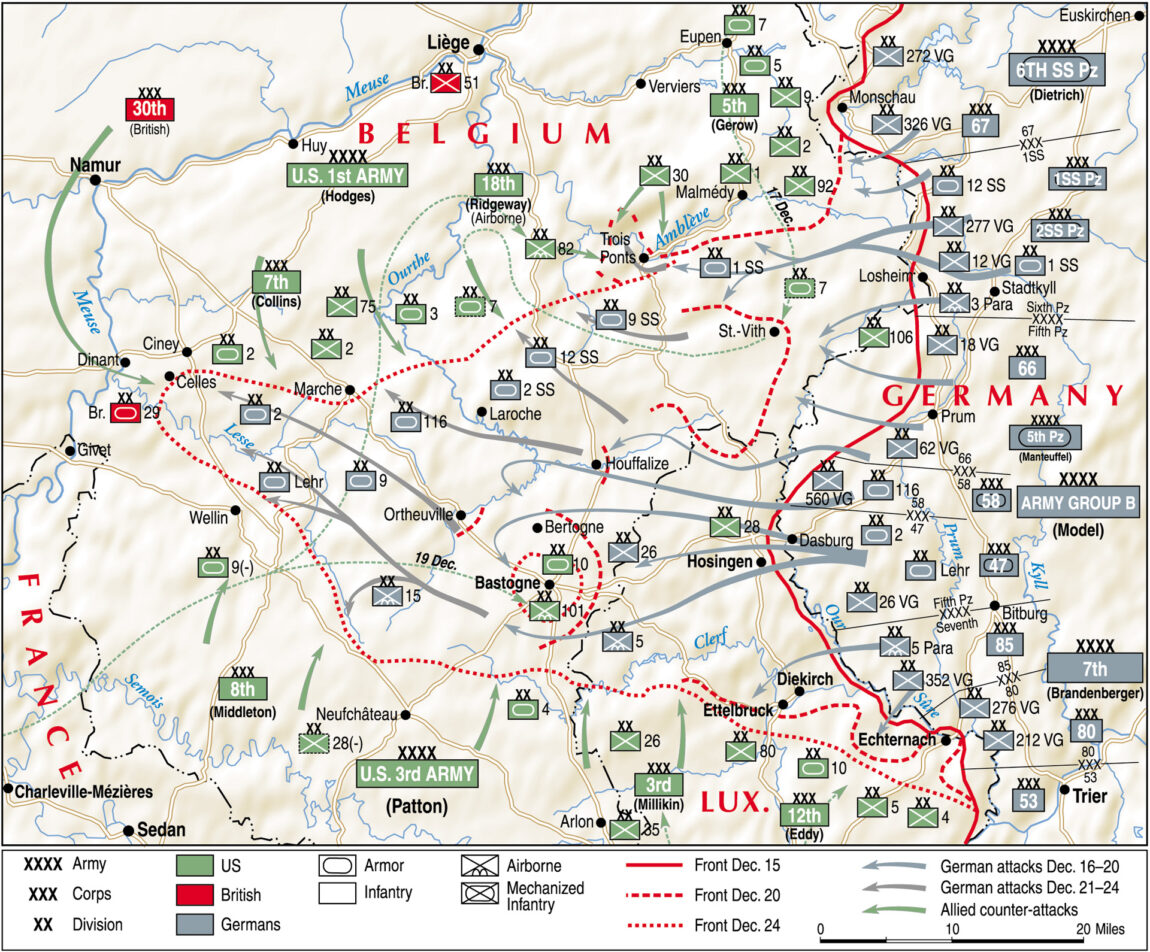

In the early morning of December 16, 1944, 80-man German shock companies from the 5th Panzer Army slipped toward the American lines in the Ardennes region under the cover of heavy fog. They intended to slip past the sleepy American outposts and get behind the Allied line in the mountainous region that straddled Belgium and Luxembourg. The shock troops cut any communication wires they found. When the main attack came, it was hoped these shock troops would be poised and ready to pounce on the American defenders before they had time to react. Behind them the rest of the 5th Panzer Army anxiously awaited the signal to attack.

German gunners readied their artillery pieces and looked at their watches. They were waiting for the order to unleash a heavy barrage on the American forces. Besides the 5th Panzer Army, two other German armies, the 6th Panzer Army to the north and the 7th Army to the south, were poised to attack the mostly unsuspecting American GIs. At 5:30 am, the order was issued for the artillery to fire. The German guns roared to life, spitting orange flames from their muzzles in the darkness. German leader Adolf Hitler’s desperate offensive gamble in the West to drive the Allies from Germany’s doorstep and possibly change the course of the war had begun.

The 5th Panzer Army was commanded by General der Panzertruppen Hasso von Manteuffel. A veteran of World War I, Manteuffel became an adherent of the concept of armored warfare in the 1930s while serving under then Colonel Heinz Guderian. Anxious to get into the war, Manteuffel saw action on the Eastern Front commanding a battalion, then a regiment, and next a brigade. Transferred to North Africa, Manteuffel proved himself a capable divisional commander in Tunisia. Evacuated in May 1943 just before the Axis forces there surrendered, a month later Manteuffel took command of the 7th Panzer Division in Russia and later the Grossdeutschland Panzergrenadier Division.

Hitler took a liking to Manteuffel, who had earned the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords, and he promoted him to full general, placing him in command of the 5th Panzer Army on September 1, 1944. Thus, Manteuffel found himself battling Lt. Gen. George Patton’s U.S. Third Army in the Lorraine region of northeastern France.

On November 2, Manteuffel was informed of the plan deceptively code-named Wacht em Rhein (Watch on the Rhine), which called for the 5th and 6th Panzer Armies, supported by the 7th Army, to smash through the weakly held American position in the Ardennes, cross the Meuse River, and drive for Antwerp. The goal was to isolate and trap the British and Canadian armies, as well the American 1st and 9th Armies. Manteuffel was shocked by the plan. As a realistic frontline commander, he believed the plan had little chance of success.

In late November, Manteuffel donned a colonel’s uniform to disguise himself and headed to the Eifel front to reconnoiter the sector he was to attack. In the rolling country of the Ardennes, heavily wooded and dotted with farmland, Manteuffel planned to make every effort to reach the Meuse River. In the northern part of Manteuffel’s sector lay the heavily wooded ridge of the Schnee Eifel where open ground existed on the northern end in the Losheim Gap. The Ardennes possessed an extensive network of roads, most of which were gravel. The twisting roads generally followed stream valleys, quite often running in a north-south direction.

Speaking with officers and soldiers manning the front line, Manteuffel was informed that in this quiet sector the Americans kept watch until about an hour after dark. Afterward, they headed to their huts to get some sleep. An hour before dawn, they returned to their positions. During the night German patrols had little problem slipping miles behind the American lines. Manteuffel believed a preliminary artillery barrage would only serve to alert the enemy of an attack. He wanted the shock companies to infiltrate enemy lines before the barrage. In a December 2 meeting with Hitler, Manteuffel obtained permission to infiltrate the American lines in his sector. Manteuffel also recommended bouncing searchlight beams off the clouds to give his troops artificial moonlight to help them move into position in the woods east of the Our River. Hitler agreed to the plan.

Using the dark forest of the Eifel for cover, the bulk of the assault divisions assembled about 12 miles behind the front on the night of December 12. Two nights later the troops moved closer to the front line. During the build up, Manteuffel issued instructions that vehicles should only move at night to avoid detection.

The 5th Panzer Army comprised the 66th Army Corps under General der Artillerie Walther Lucht, 58th Panzer Corps under General der Panzertruppen Walter Krüger, and 47th Corps under General der Panzertruppen Heinrich von Lüttwitz. Once the fighting began, Manteuffel planned to obtain Hitler’s Begleit Brigade, a division-size unit under Hitler’s direct control.

Manteuffel had some concern about the new Volksgrenadier divisions made up largely of Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe personnel who had seen little combat and had not been properly trained, although they were supposedly led by experienced officers. The 5th Panzer Army had about 396 tanks and self-propelled guns, 963 artillery pieces, four divisions of infantry, and three panzer divisions, totaling about 90,000 men.

The 5th Panzer Army was deployed north to south as follows: 66th Corps, 58th Panzer Corps, and 47th Panzer Corps. Krüger’s 58th Panzer Corps was to push west over the Our River and capture crossing points over the Meuse River between Namur and Andenne. Lüttwitz’s 47th Panzer Corps was cross the Our River, drive hard for Clerf, and then take Bastogne, an important road center, before finally pushing west to capture crossings over the Meuse south of Namur.

To the north of Manteuffel’s two panzer corps was the Schnee Eifel, which was held by the green 106th Infantry Division of the U.S. First Army. The division had recently moved up to the front line to get much needed experience, although in a quiet sector. As the area it held protruded through the Siegfried Line and posed a possible threat to the 5th Panzer Army, Manteuffel ordered Lucht’s 66th Corps to envelope and destroy the 106th Division and capture the key road hub of St. Vith. The other American units facing Manteuffel were two regiments from the veteran 28th Division, resting and refitting after suffering heavy losses in the Hürtgen Forest in November.

The Germans attacked on December 16. A report from an observation post of the U.S. 110th Infantry Regiment of the VIII Corps in Hosingen noted at 5:30 am that the entire German line was a series of pinpoints of lights. A few seconds later, shells began slamming down in the town and along the whole American line; they would continue to do so for 45 minutes, smashing buildings, splintering trees, and cutting telephone lines. A short time afterward, German armor and infantry units swept forward.

The 18th Volksgrenadier Division of Lucht’s corps, which had been posted on the Eifel salient since October and knew the terrain, was given the task of encircling two regiments of the exposed U.S. 106th Division east of the Our River. Two regiments of the German division and a detachment of self-propelled guns moved through the southern end of the Losheim Gap, while the third regiment attempted to encircle the American position from the south at the village of Bleialf.

Thirty minutes after the artillery barrage lifted, the village was attacked by the 293rd Regiment of the 18th Volksgrenadier Division. With a makeshift force of troops from the supply, headquarters, cannon, and engineer companies, Colonel Charles Cavender, commander of the 423rd Infantry, 106th Division counterattacked with support from artillery and two guns from the 820th Tank Destroyer Battalion posted nearby. Moving from house to house, the GIs drove the Germans out of the village except for a few buildings near the railroad. The Americans held the village for the rest of the day.

Things went better for the rest of the 18th Volksgrenadier farther north in the Losheim Gap. German shock troops had easily slipped past outposts of the U.S. 14th Cavalry Group posted on the border between the attacking 5th and 6th Panzer Armies and by daylight were pushing for the crossroads village of Auw to the rear of the 422nd Infantry Regiment, 106th Division. Cavalry outposts at the villages of Roth and Kobscheid north and east of Auw soon were under attack by dawn. Initially American shellfire stopped a company of volksgrenadiers at Roth. By 8:30 am, though, an urgent message reported the Germans were in the village and enemy armor was firing on the command post. It was the last message from Roth.

By 9 am, the Germans had infiltrated Kobscheid. The nearby village of Weckerath was under attack, too. The situation was becoming serious as the day progressed, and those outposts that were not already overrun were evacuated. This was part of the 14th Cavalry’s withdrawal first to the Manderfield Ridge and then two miles farther east to a ridgeline that stretched from Andler to Holzhiem. By nightfall, the 5th Panzer Army had achieved a breakthrough in the northern part of its sector.

Attacking south of the 18th Volksgrenadier was the 62nd Volksgrenadier Division, a green unit of the 66th Corps. Its objective was to breach the American line held by the U.S. 424th Infantry Regiment, 106th Division and reach Winterspelt and access to the macadam road leading to St. Vith before pushing farther west to the Meuse.

Out of the early morning mist shock companies attacked the 3rd Battalion, 424th Infantry at Heckhuscheid. In fierce fighting, the Germans were driven back as the American battalion threw in its reserve company, bagging 200 prisoners. At Eigelscheid, machine-gun and small-arms fire from a small band of GIs from the 424th cut down the inexperienced volksgrenadiers, who were attacking in bunches and firing their weapons wildly. American artillery fire added to the Germans’ misery. Despite the determined American resistance, the Germans had numbers on their side and managed to capture some of the buildings in the village. As the fighting raged the Americans were forced to give up the village and withdraw toward Winterspelt.

South of the 66th Corps, Krüger’s 58th Panzer Corps attacked on a front from Heckhuscheid to Leidenborn intending to capture bridges over the Our River. Blocking its way were two battalions of the U.S. 112th Infantry Regiment, 28th Division posted on the east side of the river. They were partially dug into foxholes and manning the captured pillboxes of the Siegfried Line. Another battalion of the regiment, which acted as the reserve, was on the west side of the river.

There was no artillery barrage in this area in the first moments of the attack. This was done to achieve complete surprise so that the Germans might capture the bridges intact. About 6:20 am, German artillery and nebelwerfers did open up attempting to knock out the Americans’ artillery and reserve positions. Despite the initial surprise and penetration by the 560th Volksgrenadier Division, which saw elements reach one of the bridges at Ouren, the GIs from the 112th Infantry forced the Germans back after bringing in their reserves and calling in artillery and mortar support.

Meanwhile, the 116th Panzer Division, attacking about 200 hundred yards south of the 62nd Volksgrenadier against the forward battalion of the 424th, was hit hard with small-arms fire. Five Panzer Mark IVs rolled into action. One was knocked out by a 57mm antitank gun, and a second one was hit with a bazooka round. The other three turned back.

Elsewhere other attacking elements of the 116th did little better, although one assault company did get behind the command post of the 1st Battalion, U.S. 112th Infantry. Daylight found the advance party of the assault company in the open. Interlocking machine-gun and small-arms fire quickly isolated them. By noon, the GIs facing them were rounding up so many prisoners they could not handle all of them. Some attacking Germans did manage to reach an American battery at Welchenhausen but were stopped cold by heavy machine-gun fire. By the end of the day the bridges were in still American hands. However, the GIs of the 112th Infantry Regiment in their exposed position east of the Our River knew the Germans would be back. One U.S. soldier scrawled in his diary: “This place is not healthy anymore.”

Attacking south of the 58th Panzer Corps was Lüttwitz’s 47th Panzer Corps. Assault companies from the 26th Volksgrenadier Division slipped across the Our River in rubber boats with orders to head west past a highway overlooking the river. Manteuffel wanted the 26th Volksgrenadier to reach the Clerf River by nightfall. Standing in his way was the U.S. 110th Infantry Regiment posted mostly in little villages which the Germans had orders simply to bypass, leaving them to be mopped up by following units. The Germans planned to capture the villages of Marnach and Hosingen, both of which controlled key roads.

South of Hosingen an American platoon was quickly overrun, while behind the village a battery came under attack. German shock companies were spotted near other villages and fired upon, and in some places pinned down by artillery fire. Bitter fighting soon raged throughout the day as the lightly armed 28th Volksgrenadier and panzergrenadiers from the 2nd Panzer Division fought for control of various villages. The GIs hung on, hammering the attacking Germans with machine-gun and small-arms fire. Mortar rounds and artillery shells came crashing down on the Germans, but they continued to fight desperately. Two companies of the 707th Tank Battalion arrived to buttress American positions in the sector.

At the Our River, German engineers struggled to construct bridges near Dasburg and Gemünd to allow the tanks and self-propelled guns of the 2nd Panzer Divisions and the Panzer Lehr Division, now bogged down in a traffic jam, to get across the river and help break through the American lines. By 1 pm, a bridge was completed near Dasburg. Ten tanks rumbled across before a following tank turned too short, hit the bridge, and plunged into the river. The Germans did not get the bridge repaired until 4 pm. By that time, the engineers had also completed a bridge at Gemünd.

With armor support and more firepower, the Germans were able to capture Marnach by midnight. The GIs still hung on in Hosingen. The 110th, heavily outnumbered, had done well, throwing the German timetable back. The 5th Panzer Army was off schedule, although it had managed a breakthrough in the Losheim Gap where it threatened to encircle the two regiments of the 106th Division. Although Manteuffel’s use of infiltrating troops had paid off in certain areas, it had not been a good day for the Germans.

On the morning of December 17, a counterattack by the 2nd Battalion, 110th Infantry Regiment at Marnach quickly bumped into advancing German infantry. Meanwhile, 18 light tanks from the 707th Tank Battalion came under fire from German self-propelled guns and panzerfausts. Eleven were knocked out. A small American force did manage to make it to Marnach, but it drew heavy German fire, and it became obvious it could not retake the town.

The Americans then shifted their focus toward halting the German advance west on the winding road toward the village of Clerf, which the 2nd Panzer Division needed to capture to reach Bastogne. About mid-morning two platoons of Mark IVs and 30 half-tracks loaded with panzergrenadiers from the 2nd Panzer Division approaching the town were met by a platoon of Shermans from the 707th Tank Battalion. Three Shermans were knocked out, while four German tanks were destroyed. The Germans diverted their column to another road.

Another platoon of Shermans moved into Clerf and knocked out the leading Mark IV, temporarily blocking the road. Nineteen more American tanks from Company B, 2nd Tank Battalion, 9th Armored Division rolled into town and were dispersed where needed.

Despite the reinforcements, the 2nd Panzer Division soon captured Clerf. Tank shells smashed into the command post of Colonel Hurley Fuller, commander of the 110th Regiment. Fuller attempted to escape with his staff but was soon captured. Clerf was in German hands, but American resistance was not done yet. At the south end of town in a chateau by the south bridge, a group of GIs held on before finally surrendering the following day.

Meanwhile, the 116th Panzer Division continued its assault on Ouren. After hammering the Americans at Ouren with artillery and nebelwerfer fire, the tanks and panzergrenadiers attacked. While the GIs staggered the infantry, the tanks pushed on, hammering the American foxholes with cannon and machine-gun fire. A platoon of self-propelled guns from 811th Tank Destroyer Battalion, Combat Command Reserve (CCR), 9th Armored Division, which had reached Harspelt, knocked out four German tanks. The return fire left only one self-propelled gun still intact. The German tanks continued to rumble toward Ouren only to come under howitzer fire from the cannon company of the 112th Infantry, which knocked out four of them.

Artillery fire from Battery C, 229th Field Artillery also helped slow the attacking German tanks, while antiaircraft half-tracks sporting quadruple mounted .50-caliber machine guns cut down the panzergrenadiers.

As the day wore on the Americans continued to hold Ouren, but their position was becoming tenuous with German infantry attempting to infiltrate and firing on their command post. The Americans received orders to evacuate the town but were unable to blow the bridges due the Germans being too close. It did not matter because the Germans later discovered that the bridges would not support the weight of their tanks. Manteuffel and Krüger had to divert the tanks south to cross at Dasburg in the 47th Corps sector. While the clock continued ticking for the Germans, more time was wasted.

The 112th Infantry ended up at St. Vith, where it joined other American troops preparing to defend the vital crossroads town. Bleialf finally fell to the southern battle group of the 18th Volksgrenadier at dawn on December 17. At about 9 am, the two German battle groups made contact, encircling two regiments of the 106th Division. The lead German battalions were then ordered to push west toward St. Vith, getting within a couple miles of the town by nightfall.

With no help available, the two trapped regiments of the 106th Division were ordered to break out toward St. Vith on December 18. In their retreat, they were advised to avoid the German buildup at Schönberg. It was on the road to this town, located about six miles east of St. Vith, that the German armor was bogged down in a huge traffic jam due to bad roads and mud.

At the same time, the 18th Volksgrenadier probed the American line a mile east of St. Vith on high ground called Prumerberg, where the 168th Engineer Combat Battalion was entrenching and waiting for the arrival of CCB, 7th Armored Division to bolster the line. Manteuffel needed the road network in St. Vith and the east-west rail line to keep German forces supplied once they reached the Meuse River. The Führer Begleit Brigade was to be brought in to help the 66th Corps take the village, but massive traffic jams to the rear of the 5th Panzer Army slowed the brigade’s advance.

To the southeast of St. Vith, Winterspelt finally fell to the 62nd Volksgrenadier. The advancing volksgrenadiers were bloodied at Steinebruck on the Our River by Combat Command B (CCB), 9th Armored Division. By late afternoon on December 17, the Americans were ordered back over the Our River. The next day they blew up the bridge at Steinebruck.

As St. Vith straddled the border of the 5th and 6th Panzer Armies, elements from the latter army threatened the village from the north. The Americans established a 15-mile horseshoe-shaped defensive position at St. Vith. On December 19, the Germans continued to probe the American defenses. Manteuffel wanted to attack, but traffic jams in the rear continued to bog down the Führer Begleit Brigade, allowing only advance detachments to arrive north of St. Vith. Concurrently, two of the 18th Volksgrenadier regiments were still focused on the two trapped 106th regiments. The commander of the 5th Panzer Army could do nothing but plan to attack early on December 20.

On that day the beleaguered 422nd and 423rd Regiments, 106th Division surrendered after a breakout attempt the previous day was stopped by German machine-gun and artillery fire. Meanwhile, Manteuffel’s main attack against St. Vith had to be delayed yet another day, for the rest of the Führer Begleit Brigade had not arrived yet. About midday a battalion of both tanks and infantry from the Führer Begleit Brigade attempted to capture Rodt northeast of St. Vith, but the U.S. 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion knocked out four of its tanks. Maj. Gen. Otto Remer, commander of the Führer Begleit Brigade, withdrew his men to wait for the rest of the brigade before attacking again.

The main attack finally rolled forward on December 21. The Germans had managed to get their artillery through the traffic jam, and at 11 am they began pounding the 7th Armored Division, parts of the 9th Armored Division, and other units holding the defenses around St. Vith.

Along the Schönberg road east of the town, the Germans advanced at 5 pm. Other assaults came down Malmédy road to the north at 6:30 pm and southeast of town at 8 pm along the Prüm road. An artillery barrage preceded each attack. Fighting was fierce as Lucht had told his division and brigade commanders to take the town no matter the cost. Multiple waves of volksgrenadiers supported by armor advanced against the American positions.

In the eastern sector, U.S. machine guns cut down many of the volksgrenadiers, but more followed. When the American machine-gun crews were killed, other GIs scrambled out of their foxholes to man them. By 7 pm, German rockets fell on the American positions and more panzergrenadiers advanced. In the intense fighting, American machine-gun crews and bazooka teams lasted only about 10 minutes before being wiped out and replaced by fresh troops.

At Prumerberg, six Panzer VI Tiger tanks rolled forward in the dark toward American tankers waiting for them to come over a rise. As they did, suddenly the night came alive with a blinding light as the Germans fired high-velocity flares. The German Tiger crews quickly knocked out the five silhouetted Shermans. The massive steel monsters then turned their attention to knocking out machine-gun crews. Volksgrenadiers soon overran the position.

By 9:30 pm, German tanks were in St. Vith, where scattered fighting continued for several more hours. With U.S. defenses breached at St. Vith, Brig. Gen. Bruce Clarke, commander of CCB, 7th Armored Division, ordered a withdrawal west of town, where new defenses were set up. But many of the American troops did not escape. Clarke estimated he had lost about half his command.

Lucht’s 66th Corps could not immediately pursue the Americans as St. Vith became a traffic bottleneck, and it took time to get the mess sorted out. Taking St. Vith had cost Manteuffel valuable time. “The delay imposed there put the entire German offensive plan three days behind schedule,” he said. “I didn’t count on such stubbornness.”

The Americans had set up a 10-mile-wide defensive position west of the town that they called the “fortified goose egg” due to its oval shape. A change of command had taken place in this sector as the U.S. XVIII Airborne Corps under Maj. Gen. Matthew Ridgway now took command of the 7th Armored Division. Allied Supreme Commander General Dwight Eisenhower was quickly sending reinforcements into the Ardennes to contain the bulge in the American lines. A change of command also took place as Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery took charge of the northern sector of the Ardennes on December 20.

Despite Ridgway’s determination to hold the goose egg until help arrived, Brig. Gen. Robert Hasbrouck, commander of the 7th Armored Division, and Clarke thought otherwise. Volksgrenadiers were already penetrating the goose-egg perimeter, and the commanders did not think it was possible to hold on. Not wanting to risk losing the 7th Armored and other defenders, Montgomery ordered them to withdraw, which they did on December 23.

Meanwhile to the south, by the evening of the December 17, Manteuffel had broken open a 10-mile gap in the American lines, and the 47th and 58th Panzer Corps poured through it toward Bastogne and the Meuse River. Manteuffel gave the task of quickly seizing Bastogne, which lay 30 miles east of the Our River by road, to Lüttwitz and his 47th Corps. Manteuffel’s orders stated, “In the case of strong enemy resistance, Bastogne is to be outflanked.” Capturing the town would then be left to the 26th Volksgrenadier and the Panzer Lehr Divisions.

The Germans were not the only ones racing to Bastogne. The paratroopers of the U.S. 101st Airborne Division, led by Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, were making a 100-mile journey by truck to Bastogne from the southwest. Through an intercepted radio message the Germans learned of the paratroopers’ pending arrival at the front. “We shall be there before them,” said Lüttwitz.

Not only was the 101st Airborne headed to Bastogne, but also the 10th Armored Division from Patton’s Third Army. General Troy Middleton, who was headquartered in Bastogne, divided the CCR, 9th Armored Division into task forces to slow the German advance.

The reconnaissance battalion of the 2nd Panzer Division encountered the first task force at a road intersection near Lullange, where it had set up a roadblock. A couple of probing attempts on the American position were beaten back. By about 11 am, Mark IVs began to arrive. Using the cover of smoke, they advanced to within about 800 yards of the Shermans of Company A, 2nd Tank Battalion.

By early afternoon more German tanks arrived and began pushing back the American infantry. The Shermans soon found themselves surrounded on three sides. By 2:30 pm, the roadblock had been overrun and Company A had been pushed back from the road junction with the loss of seven tanks. The remnants of the company escaped cross country during the night.

The bulk of the 2nd Panzer Division encountered the second task force at Allerborn, about halfway between Clerf and Bastogne, around 8 pm. Sweeping the area with machine-gun fire to drive off any infantry support, the German tanks quickly overran two platoons of Company C, 2nd Tank Battalion. The shattered survivors retreated to Longvilly, about five miles northeast of Bastogne.

A third U.S. task force positioned on high ground north of the Allerborn-Longvilly road found itself cut off. To avoid being encircled, the task force pushed northwest. On December 19, the task force reached Hardigny only to stumble into a German ambush that destroyed its vehicles and inflicted 600 casualties. About 225 GIs managed to escape the carnage.

Colonel Meinrad von Lauchert, commander of the 2nd Panzer Division, swung northwest on a poor secondary road toward Noville, bypassing Bastogne and following his orders to drive for the Meuse River. By this time CCB, 10th Armored Division had arrived in Bastogne and was quickly divided into three teams named after its commanders to defend the major roads leading into town. Team Cherry (commanded by Lt. Col. Henry Cherry) was sent to Longvilly, Team O’Hara (Lt. Col. James O’Hara) was to defend Wardin southeast of Bastogne, and Team Desobry (Major William Desobry) was sent to Noville.

The lead elements of Panzer Lehr, under Lt. Gen. Fritz Bayerlein, reached Mageret about three miles east of Bastogne around midnight. There Bayerlein was duped by a Belgian civilian into believing that earlier in the evening about 50 American tanks, 25 self-propelled guns, and numerous vehicles led by a general had passed through the village. No such thing had happened, but Bayerlein believed that Bastogne was held by a division and took up a defensive position northeast of Mageret, cutting the Longvilly-Bastogne road, and waited for morning before attacking toward the key town. That night the lead elements of the 101st Airborne, the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), reached Bastogne. The Germans had barely lost the race.

In the heavy morning fog of the 19th, Bayerlein sent a reconnaissance force toward Bastogne. The force soon reached Neffe, the location of Team Cherry’s command post. While the Americans put up stubborn defense from a stone chateau, the Germans soon discovered they had a more serious problem on their hands when columns of American infantry were spotted coming toward them from Bastogne. It was the 501st PIR probing east of Bastogne.

The aggressive paratrooper attack against Hill 510 overlooking Neffe and Mageret caused Bayerlein to believe he was facing a major American counterattack. Leaving a strong force to defend the Mageret-Neffe road and Hill 510, Bayerlein pushed southwest over terrible secondary roads to probe American defenses there.

Concurrently, Team Cherry at Longvilly was surrounded. Elements of the Panzer Lehr that had been delayed clearing a village east of the Clerf River on the 18th began to catch up with the rest of the division. Lead elements of the division, along with the 26th Volksgrenadier and six tank destroyers from the 2nd Panzer, advanced on Team Cherry, which was caught in a traffic jam consisting of vehicles from CCB of the 10th Armored, 9th Armored, and other units. Team Cherry was hit hard. About 100 of its tanks, half-tracks, and trucks were either abandoned or destroyed. Elsewhere, elements of Panzer Lehr drove Team O’Hara out of Wardin.

To the north, lead elements of 2nd Panzer struggling along bad roads reached Noville, held by Team Desobry. Receiving permission from Lüttwitz to bypass the town, a column of the division’s armor moved along a ridge to the southeast in the fog. The fog lifted, and American and German tanks began trading shots. The Americans were soon reinforced by a battalion of the 506th PIR and a platoon of the 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion. Fierce fighting broke out, but German tanks were reluctant to push into Noville due to paratroopers armed with bazookas. The German tanks that did move toward Noville were knocked out by the American tank destroyers. Noville remained in American hands.

The next morning, the Germans hammered the village with artillery fire followed by an attack by panzergrenadiers, which was hurled back. The situation was critical for Team Desobry. The road south of its positopn was cut. During the night, the Germans had captured the hills overlooking Foy, located south of Noville. McAuliffe and Colonel William Roberts of CCB, 10th Armored, who shared command in Bastogne, gave Team Desobry permission to withdraw. While paratroopers attacked Foy, Team Desobry fought its way out of Noville, reaching the safety of American lines around 5 pm. Meanwhile, German attacks to east of Bastogne were pushed back by the Americans.

While Lüttwitz began to shift his forces to the south and encircle Bastogne, the German high command persuaded Hitler to authorize reinforcing the 5th Panzer Army, which was showing the most progress of the three armies. Thus, 5th Panzer Army received the 9th Panzer, 15th Panzergrenadier, and 2nd SS Panzer Divisions. However, fuel shortages slowed their arrival. Lauchert pushed his 2nd Panzer Division west and captured a bridge over the Our River at Ortheuville. At that point, his tanks and vehicles sputtered to a stop when they ran out of fuel.

Lüttwitz reinforced the 28th Volksgrenadier with a contingent of the Panzer Lehr and ordered the rest of the division to head west for the Meuse. The 26th Volksgrenadier kept up the pressure on Bastogne, and by the night of December 20 the town was effectively surrounded, although the western sector was not strongly held by the Germans. Two days later Lüttwitz attempted to bluff the Americans in Bastogne by offering them the chance to surrender. McAuliffe simply replied, “Nuts.”

Americans in Bastogne by offering them the chance to surrender. McAuliffe simply replied, “Nuts.”

“If you don’t understand what ‘Nuts’ means,” said Colonel Joseph Harper, commander of the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment, to the two German officers who brought the surrender offer, “In plain English it is the same as ‘Go to hell.’” When Manteuffel learned of the surrender offer, he was furious at Lüttwitz for his unauthorized action.

Krüger’s 58th Corps, after breaking through the 112th Infantry, pushed west between St. Vith and Bastogne, encircling a battalion of the 3rd Armored Division at Marcouray. At Hotton in an attempt to capture the bridge over the Our River, the Germans met with a galling fire. The 116th Panzer was facing the 51st Combat Engineer Battalion and elements of the CCR, 3rd Armored Division. Believing he was facing a strong American force and that it would take too much time to force a crossing, Krüger ordered his panzer division to head south to cross at La Roche. Valuable time was wasted sorting out traffic issues and repulsing American attacks.

The 2nd Panzer received enough fuel to allow its reconnaissance battalion to continue the race to the Meuse, skirting between the U.S. 84th Division at Marche, where a blocking force was soon deployed, and Rochefort. The latter was captured by Panzer Lehr, which was supposed to secure the German left flank on its drive to the Meuse.

On December 23 the cold spell that had improved the roads also cleared the skies, allowing Allied planes to attack the Germans and drop supplies into Bastogne. That day the reconnaissance battalion of 2nd Panzer got within a few miles of the Meuse River. The advance guard of 2nd Panzer, which had received some fuel, soon arrived nearby the next day. Three Mark V Panther medium tanks from the reconnaissance battalion were knocked out by British tanks on patrol around Dinant as the British XXX Corps had been positioned to hold the crossings over the Meuse River. The Germans had reached their high water mark in the Ardennes offensive.

The Germans soon had other concerns when the 2nd Armored Division, VII Corps attacked, intending to cut off the 2nd Panzer’s spearhead on Christmas Day. Two days later the spearhead was crushed despite breakout attempts and failed efforts from the Panzer Lehr Division and the rest of the 2nd Panzer Division to break through. Six hundred troops managed to escape on foot during a snowstorm. It was now clear to Manteuffel that further attempts to reach the Meuse would be useless.

Things were no better at Bastogne, where early on Christmas morning the Germans made a large thrust under the cover of darkness to avoid Allied aircraft. The 15th Panzergrenadier Division, under Colonel Wolfgang Maucke, who had just arrived the night before, made the main attack between Champs and Hemroulle to the west of Bastogne reinforced with elements of the 26th Volksgrenadier Division. The tanks quickly overran two companies of the 1st Battalion, 327th Glider Regiment. Despite being overrun, these troops hunkered down in their foxholes until the German tanks had passed by and opened up on the next wave of advancing panzergrenadiers.

The German tanks split up. Some headed to Hemroulle and others toward Champs. Both these groups were shot to pieces by elements of the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment and 705th Tank Destroyers. When the smoke finally cleared, all 18 German tanks were knocked out, and supporting panzergrenadiers were either killed, wounded, or captured. Smaller infiltrating attacks by the 77th Grenadier Regiment, 26th Volksgrenadier had initial success around Champs, but these troops were soon pinned down.

The following morning a desperate effort in the direction of Hemroulle was repulsed by American artillery and tank destroyers. Elements of Patton’s Third Army pushing north through the German 7th Army made contact on December 26 with the determined defenders of Bastogne, thus breaking the siege. Heavy fighting continued in the sector throughout the following week as the Americans attempted to secure the supply corridor between the Third Army and U.S. forces in Bastogne.

Hitler was adamant that Bastogne be cleared. To do this, the Germans assembled an army group drawn from elsewhere in the Ardennes that included the battered 1st SS Panzer Division, 3rd Panzergrenadier Division, and the Führer Belgeit Brigade to help take the town. Eastern front veteran Maj. Gen. Karl Decker’s 39th Panzer Corps was brought in to handle the Bastogne operation. He attacked during a snowstorm on December 28 with no success. The following day Decker’s corps was put under the command of Lüttwitz, becoming Army Group Lüttwitz.

Manteuffel launched a major attack on December 30 with the 47th and 39th Panzer Corps against the supply corridor from both the northwest and southeast, which was proceeded by an artillery and rocket barrage. Patton launched an attack the same day. When the smoke had cleared after a day of bloody fighting, the Germans had failed. The corridor remained open, and Bastogne remained firmly in American hands.

Although fighting would continue into January before the bulge was erased, the German offensive was over. The Germans lost about 100,000 men killed, wounded, or captured. In contrast, the Americans suffered about 81,000 casualties. The 5th Panzer Army had advanced the farthest of the three German armies participating in the winter offensive. Still, the Germans gained nothing and lost a great deal. A high-ranking German officer said that the Ardennes campaign had “broken the backbone of the Wehrmacht on the Western Front.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments