By Blaine Taylor

At the mention of the letters “SS,” an image springs to mind of ruthless German troops, the epitome of the Nazi/Aryan ideal: tall, strong, blond-haired, and blue-eyed, enthusiastically ready to fight and die for Germany and their beloved Führer, Adolf Hitler.

The typical SS man has also been portrayed as a hardened criminal, someone without moral scruples—someone happy to murder defenseless civilians simply because he was told that it was his patriotic duty to wipe out whole populations due to their ethnicity or religion that were deemed a threat to Germany and the “Ayran race.”

This image has been created by hundreds of books, films, and television documentaries, but what is truth and what is fiction? And how did a small unit originally created to serve as Adolf Hitler’s bodyguard become a much feared combat force? Perhaps these questions can be answered by briefly examining how the SS came into existence and looking at the men most responsible for its creation and deployment in combat.

As one of Hitler’s most faithful sycophants, Heinrich Himmler was rewarded for his loyalty when his Führer gave him the command of the SS (Schutzstaffel, or Protection Detail) in 1929—Hitler’s personal bodyguard. Almost immediately, the meek looking former chicken farmer began turning the small unit into an instrument of terror and military power.

The bespectacled Bavarian was born into a Catholic family in Munich on October 7, 1900. As he matured, Himmler became attracted to nationalist causes and racial theories that posited that Germans and other Nordic or Aryan types were the “master race” and destined to rule the world. In 1923, he joined the tiny Nazi Party and began rising in its inner circle. On January 6, 1929, Hitler appointed Himmler Reichsführer-SS, or National Leader, of the 280-man SS detachment.

Himmler used this appointment as an opportunity to develop the SS into what would become the elite corps of the Nazi Party. By the time Hitler became chancellor in January 1933, the SS numbered more than 52,000. As the nation slowly marched toward war, the SS was transformed from a small detachment whose original function was to protect Hitler at meetings, rallies, and public appearances into a full-blown army of fanatical soldiers wholly dedicated to the racial and political ideals of National Socialism.

Three men ultimately aided Himmler in this transformation of the SS: Josef “Sepp” Dietrich, Theodor Eicke, and Paul Hausser. Who were these men and other prominent SS leaders, and how did it happen that there were armed SS formations fighting at all in Poland in 1939—despite Hitler’s public pledge in 1934 that the regular German Army (Wehrmacht) was and remained the “sole bearers of arms” of the state?

In September 1934, the official announcement of the formation of the armed SS Verfuhrüngstruppe (SS Special Purpose Troops, or SS-VT) was made, and two units were established, one in Hamburg and the other in Munich.

Simultaneously, with the establishment of concentration camps to hold political prisoners, Heinrich Himmler reorganized all the camps’ SS guards into the SS Totenkopfverbande (SS Death’s Head Units), under Theodor Eicke, one of a trio of SS men who had executed Ernst Röhm, chief of staff of the Sturmabteilung (SA, also known as the “Brownshirts” or Storm Troopers) in his cell during the Nazi “Blood Purge” of June 30-July 2, 1934.

Also taking part in the overall “national murder weekend” or “Night of the Long Knives” was Josef “Sepp” Dietrich, commander of Hitler’s own security unit, the SS Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler (LSSAH, or SS Adolf Hitler Bodyguard).

In reward for getting rid of the leadership of the SA, whose growing size and influence threatened his rise to power and legitimacy, Hitler made all SS units independent from Storm Troop command for the first time, as units reported directly to Himmler. The LSSAH was a sole exception, however, as Sepp Dietrich reported to Hitler alone, thus bypassing a miffed Reichsführer-SS Himmler.

The weapons for the newly formed Armed SS troops (Waffen-SS) were provided by the German Defense Minister, Army Col. Gen. Werner von Blomberg, thus irking the nettlesome, aristocratic, prickly, monocled commander in chief of the German Army, Col. Gen. Werner von Fritsch.

Brought in to administer the new SS-VT were three men who, alongside Dietrich, would later write the combat historical record of the vaunted Waffen-SS across the length and breadth of conquered Europe: Paul Hausser, Felix Steiner, and Willi Bittrich. All three men would become high-ranking SS generals during the wartime years, as would both Dietrich and Eicke.

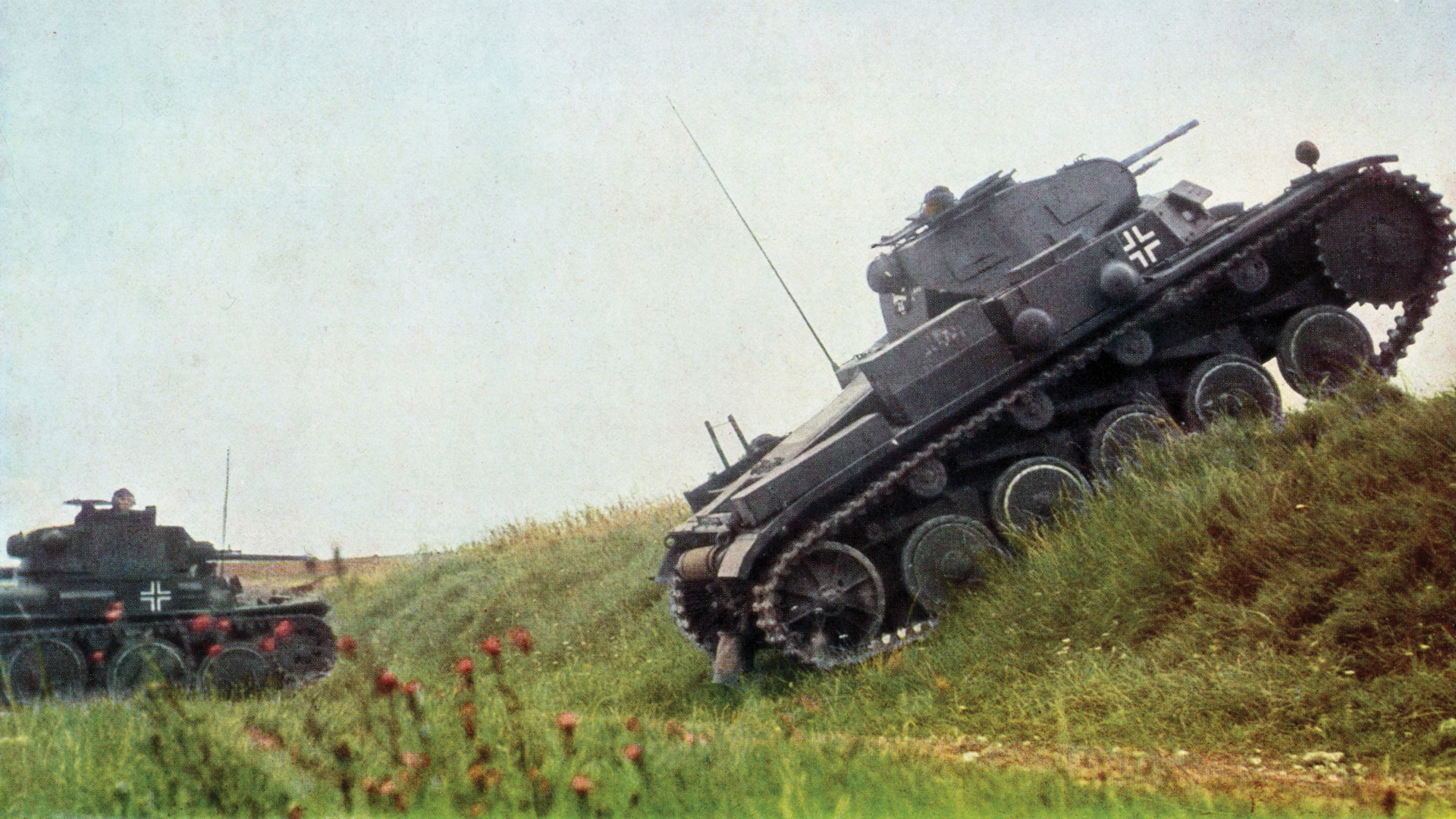

During the years 1934-1939, the old line, conservative “reactionary” generals of the regular German Army derided Hitler’s showboating, elite troopers in black—and later in field gray—as mere “asphalt soldiers,” good for effect but not for actual fighting. They were in for a surprise.

At the head of almost 1,600 men (including a motorcycle detachment), Dietrich led the way in 1935 into the delirious, formerly French-occupied Saarland and paraded his Leibstandarte there for the next five days. Hitler granted his beloved LSSAH several distinctions at this time: only it was allowed to wear white accoutrements with its black uniforms and bear the SS runes on its collar tabs without a unit number. According to his eldest son, Dietrich designed the new SSLAH uniforms himself.

As the showpiece unit of the Nazi regime, the Leibstandarte was gaining worldwide fame as an elite unit on par with the French Foreign Legion, the English Coldstream Guards, the Italian Bersaglieri, and the United States Marine Corps.

By the end of 1936, the LSSAH possessed both trench mortars and armored cars. Relations between the Army, the LSSAH, and the SS-VT remained good. Continuing his buildup of close ties with the Army, Dietrich developed a harmonious relationship with panzer leader General Heinz Guderian, who told him that the LSSAH would take part in the peaceful invasion of Austria—within 48 hours!

Beginning on March 12, 1938, it was an entirely pacific occupation with the vehicles even bedecked with flowers and greenery. By May 1938, SS Generals Dietrich and Hausser were feuding over the formation of a fourth SS-VT Standarte unit in newly Nazi-occupied Vienna named Der Führer (The Leader).

At the end of September 1938, the LSSAH took part in military training exercises at the Grafenwöhr training facility in southeast Germany. For his next “peaceful” occupation—that of Prague and the rest of Bohemia and Moravia on March 15, 1939—Hitler again teamed Guderian with Dietrich for the operation.

Parade ground troops, SA murderers, and occupiers of peaceful countries though they might be, how would the LSSAH and the SS-VT units, military analysts wondered, fare in actual combat? The answer was not long in coming. In Poland, as in the previous operations, Dietrich’s men were placed under Army command. Now the former NCO of World War I began World War II as a commanding general in the field.

Born at Hawangen in Upper Bavaria in 1892, Dietrich was a butcher’s apprentice who joined the Bavarian Army in 1911 and served in the Great War as a sergeant. A policeman following the war, he joined the SA in 1923, held a series of odd jobs, and then joined the Nazi Party in 1928.

Named an SS brigade leader in 1931, on March 17, 1933, Dietrich set up the Berlin SS Guard Staff as the new Chancellor Adolf Hitler’s bodyguards, the genesis of the later LSSAH, established in September 1933. (It should be noted that Hitler’s bodyguard prior to his becoming reich chancellor on January 30, 1933, was Party-funded. After that date, the SS unit went on the government payroll.) Dietrich remained its commander until July 1943, seeing it evolve into divisional and larger strength. He went on to become a highly decorated armored corps and panzer army leader.

Also born in 1892, at Hampont in Alsace-Lorraine, Eicke served as an Army paymaster during the Great War of 1914-1918. Afterward, he worked as both a policeman and businessman, as well as head of security for the German chemical firm I.G. Farben from 1923-1932.

Having joined both the Nazi Party and the SA in 1928, Eicke also entered the SS in 1930, where he, unlike Dietrich, enjoyed a good working relationship with SS head Himmler. In 1933, Himmler named Eicke commandant of the new SS concentration camp at Dachau, outside Munich. A decade later, Eicke had risen to become Inspector of Concentration Camps, as well as chief of the feared SS Death’s Head (Totenkopf) combat units. In 1939, these were combined into the Totenkopf Waffen-SS Division.

Paul Hausser was the third, and perhaps the most important, formative figure of the early armed Party formations. His biographer called him, “The singular greatest influence on the development of the Waffen SS.”

Born in 1880 at Brandenburg/Havel, Paul Hausser served as an officer on the staff of German Army Group commander Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria during World War I, and also saw combat in France, Hungary, and Romania. After the war, he served in the renegade Free Corps, then in the Weimar Republican Army, until he retired as a lieutenant general in 1931 at the age of 51 after 40 years of service. Thus, he had a far more exalted military record than Dietrich and Eicke combined, but he is less well known today in Nazi history.

Hausser joined the SS in 1934 after having been a member of both the Stahlhelm (Steel Helmet) veterans’ association and the SA. Appointed Inspector of SS Officer Schools in 1935, Hausser, as Himmler’s man, organized a trio of armed SS regiments: Deutschland, Germania, and Der Führer.

Under his leadership, SS armored tactics were developed and the first camouflaged clothing ever used by a military unit was introduced, made famous by the Waffen-SS during the war on fronts east, west, north, and south.

In Poland on October 19, 1939, the SS-VT was created as a full division with Hausser as its commanding officer. He lost his right eye in 1941 and commanded the first formed SS corps in 1942.

These, then, were the main figures who formed the new “combat” SS as it began to fight its first campaign when the Third Reich invaded Poland on September 1, 1939.

At the war’s outset, the German Wehrmacht consisted of more than 100 active and reserve divisions, plus a cavalry brigade. These included five panzer (armored) divisions of about 300 tanks each, or 1,500 in all; four light divisions of lesser numbers of tanks, and a quartet of motorized infantry divisions entirely equipped with motor vehicles; in 1939, the artillery and supporting weaponry were mostly horse-drawn. Overall, at the start of the war the Wehrmacht encompassed 2,500,000 trained soldiers, both on active duty and held in reserve units.

Conversely, the 1939 Polish Army consisted of but 280,000 men in 30 infantry divisions, 11 cavalry brigades, a pair of mechanized brigades, plus supporting specialist units. This peacetime force also drew on three million trained and partially trained reservists. Upon wartime mobilization, these reservists brought the standing units up to wartime strength and also potentially constituted an additional 15 reserve divisions.

The German Luftwaffe had an overwhelming superiority over the Polish Air Force, as did the German Navy in the Baltic Sea and elsewhere.

The Fall Weiss (Case White) provided an opportunity for the Germans to put their Blitzkrieg (Lightning War) concepts of coordinated air-ground operations to a test. More than 60 German divisions, the bulk of its fighting ground force, were duly committed to the campaign.

The general plan was to annihilate the Polish Army in the east before the French Army could intervene decisively in the west against the Siegfried Line. Hitler also knew that his secret, Nazi-Soviet pact ally—the Red Army—would invade stricken Poland from the east 16 days after the German campaign began on September 17, 1939. Thus, Poland would be crushed like a walnut between the nutcracker of two vastly superior forces.

At a top-secret meeting of his senior commanders on August 23, Hitler declared that Poland would not merely be occupied, but destroyed. The SS Death’s Head units were “to kill without mercy the entire Polish race” if necessary to force Poland’s quick surrender.

Indeed, stated Army Field Marshal Fedor von Bock later to his subordinate staff officer Fabian von Schlabrendorff, “At the same time, Hitler informed the generals that he would proceed against the Poles after the end of the campaign with relentless vigor. Things would then happen which would not be to the taste of German generals. By this Hitler meant to warn the Army not of the notorious liquidations, but of the destruction of the Polish intelligentsia, in particular the priesthood, by the SS. He required of the Army that the generals should not interfere in these matters, but restrict themselves to their military duties.”

These, then, were the atrocities mentioned in official after-action combat reports made by Army General Johannes Blaskowitz that began during the fighting and continued afterward as well.

On September 12, Armed Forces Intelligence Chief Admiral Wilhelm Canaris complained to Colonel General Alfred Jodl on Hitler’s command train, “They would have to accept the fact that the SS, the Security Police, and such organizations would be employed together to carry out these very measures. Thus, at the side of each military commander a corresponding civilian official would be appointed.”

Indeed, two days later an Army military police sergeant-major and a gunner from “the only SS artillery regiment which served in Poland” collected 50 Jews into a synagogue, where they were shot after having worked on a bridge as forced labor that day. Both soldiers were later acquitted under the terms of a general amnesty.

Asserted historian Gerald Reitlinger, “Such incidents were common during the 18-day campaign,” but the real “SS reign of terror,” in Ambassador Ulrich von Hassell’s diary entry words, began after the military campaign concluded. The actual combat fighting had begun it, however.

In all, 18,000 SS men in field gray uniforms fought in Poland, including the LSSAH, the Totenkopf, and the SS-VT units—all reformed and combined into full combat field divisions as the new Waffen-SS of October 1939. The Leibstandarte became the new 1st SS Field Division, and the Totenkopf the 2nd. In addition to SS General Reinhard Heydrich’s Einsatzgruppen (Special Action) killing groups, Himmler retained three full regiments in Poland of Eicke’s Death’s Head units—numbering 7,400 men in all—to “resettle” captured Jews “to the east,” from which they never returned.

Thus, these killing groups became the forerunners of later such factions in Russia, and after that, of the overall Holocaust death camps, all located in conquered Poland. Eventually, new Death’s Head killing units replaced the SS field combat divisions, which went on to fight more campaigns throughout 1941 in the Balkans and in the Soviet Union.

Speaking to senior SS commanders in 1943, Himmler marveled that the expansion of his units had been “fantastic,” and “at an absolutely terrific speed,” in the first year of the war, 1939-1940, with only, at the outset, “a few regiments, guard units, 8-9,000 strong––that is, not even a division; all in all 25-28,000 men at the most.”

Historian George H. Stein describes the contribution of the Waffen-SS as “modest, but not negligible.” The main body of the SS-VT was shipped to East Prussia during the summer of 1939 in regimental combat groups that were attached to larger Army units. These included the SS Regiment Deutschland, the just created SS artillery regiment previously noted, the SS Aufklärungs Sturmbann (Reconnaissance Battalion) that was linked to an Army armored regiment, to form the 4th Panzer Brigade under Army command.

In like fashion, SS Regiment Germania was connected to the German Fourteenth Army in East Prussia’s southern area as the jumping-off point from which to strike into Poland. A third SS regimental battle group included Sepp’s own SSLAH and the SS Pionier Sturmbann (Combat Engineer Battalion) within the German Tenth Army, which assaulted Poland without warning via Silesia.

The SS Totenkopf Sturmbann “Götze” morphed into the reinforced infantry battalion renamed Heimwehr (Home Guard) Danzig that fought both in and around the embattled former League of Nations’ Free City, today’s Polish port of Gdansk. One SS regiment that saw no action in Poland was Der Führer, due to unfinished training.

Without doubt, the SS-VT received its actual baptism of fire on the plains of Poland, yet it was given only grudging, backhanded Army praise afterward. Indeed, the regular Army generals noted that SS troops suffered “proportionately much heavier casualties than the Army,” and this was blamed on poor SS officer performance. The latter, in turn, blamed the Army’s scattered leadership of its troops in strange units “often given difficult assignments without adequate support.”

What the Army generals really wanted was the total disbandment of the Waffen-SS as a growing, Röhm/SA-like updated threat to them, but Himmler, with Hitler’s support, succeeded instead in acquiring a nearly independent SS army under the command of its own officers.

Thus, for the rest of the war Himmler and Hausser got their SS infantry and armored divisions, but they were divided among the larger regular Army and corps formations. Most importantly, they remained under Army command until the end of the war.

Had Sepp Dietrich won the Battle of the Bulge during 1944-1945, he might very well have become the first SS field marshal, in command of a fully independent fourth branch of the Armed Forces—an SS Army—but he didn’t.

The Leibstandarte suffered its first casualties: seven killed and 20 wounded. Hitler followed the unit closely from his train, marked “Sepp” on the maps wherever the LSSAH advanced, gave “his” unit the toughest assignments, and even visited it personally in the field at Guzow on September 25, 1939.

During 1936-1939, Dietrich had taken armored warfare courses both at Zossen outside Berlin and at the Wunsdorf Tank School, but Willi Bittrich later asserted that “the commander,” as he was called, couldn’t read a map properly. Nevertheless, the LSSAH performed well, at least militarily. SS troopers fought stiff Polish Regular Army resistance over a number of towns and villages.

In one battle, Sepp’s own forward command post was almost cut off but, reinforced, he went on to win the day. By September 9, his unit had been transferred to be in on the German drive on Warsaw at Hitler’s insistence, to reap even more Nazi glory.

Rudolf Lehmann, a veteran of the LAH, provided a dramatic account of his unit’s first battles: “On August 31, 1939 … the leading elements of the Regiment began to march toward the [Polish] border.… The mission for September 1, 1939 … was as follows: ‘To capture the bridge at Gola in a surprise attack, and to open the crossings over the Prosna at Bolesalwice, Wieruszow, and as far as Weglewice from the back. It is then to halt and secure the Prosna bridges until the arrival of the leading elements of the 10th and 17th Divisions.…’

“The attack missions were assigned as follows: ‘An advance detachment is to open up the crossing over the Prosna in a surprise attack beginning at 4:45 am, September 1, and then to proceed directly along the designated march route.

“‘Armed reconnaissance as far as the railway line to the east of Wieruszow, and as far as the crossing over the Prosna west of Wieruszow.… The reinforced armored reconnaissance car section’ and two other units ‘are to join the bulk of the unit, and follow the advance detachment.’

“‘Units of it are to move ahead to cover the right flank from Gola via Wojcin, the eastern edge of Wiewiorka, and Point 185 in the Sokolniki Forest. The first attack objective of the reinforced…car section’” included those key crossings.

When the attacks began, “After surprise fire on the [Polish] customs station by the light infantry, an assault detachment … waged a surprise attack on the crossing over the Prosna.

“Hand grenades exploded, several shots sounded through the air, and the obstacles were blown into the sky. The light armored vehicles entered at top speed into Gola, and the infantry assault troops seized the bridge over the river undamaged…. Heinrich Bauch of the Engineer Troops had removed the fuse from the pot filled with [demolition] explosives in time, and thus preserved the bridge for our advance.

“Ten minutes after the war started, it had already ended for the Polish company! The average age within our storm troops was 19 years, and their officers at 25.”

Officer Kurt Meyer—later nicknamed Panzer Meyer as the notorious commander of the 12th SS Panzer Division (“Hitler Jugend”)—recalled, “I was suddenly standing in front of the corpse of a Polish officer; a round in the throat had killed him. The warm blood was spurting from the wound. Yes, this was war!”

Lehmann continued, “The motorcyclists ground their way though the deep sand of the village streets of Gola and Chroscin under constant sniper fire,” as well as “thick morning fog and enemy contact along the southern edge of Boleslawez. The first heavy armored car rolled to a smoking halt; its wheels had hardly stopped when the second one was also destroyed. Both armored cars were about 150 meters in front of an antitank gun.

“The first heavy vehicle was hit by three antitank rounds from the southern edge” of the town, with one crewman slain. A later armored car casualty report listed a trio of dead, with another badly wounded and one but slightly.

Lehmann said that the Polish troops allowed “the spearhead of the advance detachment to pass, then opened fire on it, as well as SS infantry, from fortified field positions. Polish cavalry came galloping out of the smoke screen … charging directly toward the SS troops. It was only when the motorcycle platoon opened fire and brought down some horses that the fierce cavalry troop galloped back into the fog.”

At 9:20 am, the city of Boleslawice was captured by the SS after fierce street battles. “In the meantime,” said Lehmann, “the unit … assigned to protect the right flank had come into combat with the eastern extension of the Polish fortifications in Bolesawice, near Wojcin.…

“Both spearheads battled on until 12:55 pm … at first through Wojcin” where one SS trooper was fatally wounded, “and later through the terrain to the north across Wiewiorka; and to the left the bulk of a reinforced battalion … through the village along the roads … to the north edge of Kamionka.”

The Polish resistance grew more stubborn, “reinforced by high-angle and flat fire from the higher ground of the Sokoniki Forest, and from the commanding position at Meleschin.” There the German advance came to a halt due to a counterattack carried out by two companies of Polish soldiers.

Lehmann said, “With the brilliant support” from another LAH unit—“deployed for the first time—Point 185 was taken by 3:30 pm,” the support unit itself coming under Polish artillery fire. “Regimental headquarters followed to the western edge of Kamionka,” the veteran added.

The Polish forces fought with a tenacity that surprised many of the German commanders and inflicted numerous casualties on the invaders. Lehmann recalled that a machine gunner in one of the armored cars was killed in action. “By nightfall,” he said, “both Polish battalions left their previous positions in the dark and took up positions in the forest.

“The approaching darkness hid the day’s destruction. The battlefield’s misery was only visible in the illumination of nearby fires…. The Regiment had fought reinforced border patrols … that had been ordered to hold the major roads parallel to the frontier as long as possible, and to provide cover for the advance units of the Polish 19th Division and a cavalry brigade” operating in the contested area.

Of the later Battle of the Bzura River—reportedly the largest action of the entire campaign—Kurt Meyer recalled, “The finest Polish blood mixes with the water of the river. The Poles’ losses are awful.” The 10-day battle ended in a German victory on September 19, 1939.

Overall, many of the SS men considered that their Polish foe was more adept at hand-to-hand fighting than they were. One who had firsthand knowledge of this was Meyer, with one Polish soldier along foxholes on the edge of the Kampinos Forest.

“Another popped up behind me from the bushes along the bank,” Meyer wrote. “I had overlooked him.” But Meyer’s platoon messenger felled the attacker with a single round. “We were exhausted, physically and emotionally. Each man lay down and slept where he had been standing. Life is all-in-all, yet it hangs by one silken thread.”

Thus had the LAH helped stop in its tracks the Polish Army’s war cry of “On to Berlin!” But the Poles had, by their overall resistance, shaken Hitler’s belief that his nation’s military was an irresistible force and cost the Germans “an entire armored division.”

The German Army, wary of a separate SS army under Himmler, was reluctant to praise the wartime performance of the LAH. In fact, some historians have called the unit’s combat performance “slipshod,” with the regiment actually transferred from one Army command to another while in Poland during operations.

In addition, other sources provide impressive Polish accounts of civilians being shot out of hand by the LAH: “The participation of the LAH thus came to an ignominious end.”

Already, the LSSAH was gaining a reputation for erratic, “wild firing,” the excessive burning of enemy villages and, during the remaining battles, for being trigger-happy, wiping out the Polish forces on the Vistula River and around the city of Modlin.

By the time Warsaw fell on the 27th, the Leibstandarte had lost 108 killed, 292 wounded, 14 lightly wounded, three missing in action, and 15 from accidental causes. For his part, Sepp Dietrich considered the Polish Army to have been well led and praised the Poles as being “worthy opponents.”

Meanwhile, during the invasion, Theodor Eicke’s SS-VT “Death’s Head” units were reportedly slaughtering Polish intellectuals and Jews.

The SS-VT had no tactical input into the German victory in Poland. Instead, its military capabilities were used to terrorize the civilian population by hunting down straggling Polish soldiers, seizing farm produce and livestock, and torturing and murdering large numbers of Polish politicians, nobles, business figures, clerics, Jews, and the hated intellectuals.

Eicke’s trio of Death’s Head regiments—Oberbayern, Brandenburg, and Thüringen—were gathered as independent action groups in Upper Silesia before the invasion. The first two followed in the wake of the German Tenth Army, operating between the Vistula River and Upper Silesia south of Warsaw. Brandenburg followed General Johannes Blaskowitz’s Eighth Army over large tracts of Poznan and the full west-central part of the country.

Operating from Hitler’s command train, Eicke, as Higher SS and Police Leader, answered not to the furious Blaskowitz, but to Himmler alone and directly, in Poland as well as on his command train, code named Heinrich.

Following the conclusion of the fighting, Eicke’s three Death’s Head regiments, the regular SS, and Reinhard Heydrich’s SD all answered to Eiche when the Army relinquished control of the occupied Polish provinces of Poznan, Lodz, and Warsaw.

Villages were burned and Jews and others were shot “while trying to escape,” as well as “suspicious elements, plunderers, insurgents, and Poles,” in general. Savage SS measures were taken against the cities of Wloclawek (renamed Leslau in German) and Bydgoszcz (Bromberg). SS Regiment Brandenburg began a four-day “Jewish Action” on September 22 that included plundering Jewish shops, arrests, and burning and dynamiting synagogues.

As the war went on, additional SS units were raised and fought on virtually every front, gaining for themselves a reputation of being fearless, ruthless fighters.

With the Third Reich collapsing in the spring of 1945, Heinrich Himmler, in April 1945, asked Count Folke Bernadotte, the vice president of the Swedish Red Cross, to transmit an offer of surrender on the Western Front to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme commander of the British and American forces. When Hitler learned about Himmler’s “treachery” on the night of April 28-29, 1945, he stripped Himmler of all his offices and ordered his arrest.

But Himmler escaped from Berlin, headed north, and disguised himself as an ordinary soldier, hoping to blend into the tens of thousands of German prisoners of war. However, he was captured by the British. Before he could be made to stand trial for his crimes, he committed suicide on May 23, 1945, by taking poison.

As the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Holocaust Encyclopedia states, “A skilled organizer and a capable manager who understood how to obtain and use power, Himmler was the ideological and organizational driving force behind the rise of the SS. Moreover, he understood his SS men and knew how to secure their loyalty to his own person and to the concept of the Nazi elite to which they belonged.”

The SS suffered a high casualty rate during the war. One estimate says that 180,000 SS men were killed, 400,000 wounded, and 40,000 missing—over one third of its total number.

And what became of Himmler’s three main lieutenants?

After several postwar trials and imprisonments (he was sentenced to life for being in overall command of the SS unit that murdered U.S. prisoners at Malmedy, Belgium), Sepp Dietrich was released in 1958 and became head of HIPA, the Mutual Help Association of Former Waffen-SS Members, which was co-founded by Paul Hausser. Dietrich died of a heart attack in 1966 at age 73 and received a military funeral in Ludwigsburg that was attended by 7,000 of his old comrades. Hausser gave the eulogy.

Theodor Eicke was transferred from his position as overseer of concentration camp guards to command the SS Totenkopf Division in combat. While serving as the commanding general of the division, Eicke died when his light command plane was shot down by the Russians near Orelka, on February 26, 1943.

Paul Hausser led a corps at Kursk and, after taking command of the Seventh Army in 1944, he was wounded during the Battle of the Falaise Gap. He was later promoted and given command of Army Group G but was then relieved of his command. Hausser, unlike Dietrich, was not indicted for war crimes. Chairman of the postwar SS veterans’ organization HIPA, Hausser died as a successful author at age 92 in 1972.

As Ambassador Ulrich von Hassell so truly noted, “The SS reign of terror” in hapless Poland had begun, ending only when the Red Army liberated it in 1944-1945. After the war, apologists for the Waffen-SS like Paul Hausser tried to separate the twin records of the “combat” SS units from that of the Death’s Head camp guards. In reality, however, they were one and the same, with much crossover from one force to the other.

That debate, too, continues unabated.

The SS were very well trained soldiers who would give their lives for Hitler and fight to the death. They were very brutal during combat and most of the officers were cruel bastards. Some would not take prisoners or if they did they would be executed afterwards .

It astonishes me how so many evil Germans got off lightly and went on to lead successful lives after the war.

The allies in victory showed much more mercy than the Germans ever did.

I think the WAFFEN SS and other SS units were nothing but murderers, disguised, as soldiers they were a disgrace to the uniform,.

I believe that GOD has a special place in hell

For them for the atrocities they committed against the jewish people I think a lot of them got off easy for the evil they committed.

The SS units did very poorly against the Poles. The article cites SS Nazi German propaganda instead of actual historical research. The SS Germania regiment was decimated by a night attack by the 49th Hutsul Rifles on Sept. 14. One of its battalions was wiped out, its commander killed, and the survivors fled in panic leaving behind most of the regiment’s supplies and heavy equipment. LAH suffered heavy losses by repeatedly blundering into Polish defenses.

The main SS contribution was mass murder of Polish civilians. Despite this article, the majority of the killings in 1939 were of non-Jewish civilians and POWs, though Jews were also targeted. (The mass killing of Jews would ramp up later.)

The caption about the 7TP tank is also wrong. They were highly effective and superior to the PZ I and II, just not enough of them.

“peaceful invasion of austria….”

***sigh***

the overall casualty figures on the c. 30 Waffen-SS divisions are stuff-and-nonsense. SS divisions were routinely and repeatedly decimated as shock troops on offense and stand-and-die units on defense throughout the war. About 900,000 Germans AND other European volunteers served in these divisions; c. 500,000 were KIA. Battlefield and other atrocities? Waffen-SS units were little better or worse than regular Wehrmacht units; and the German Army as a whole no better or worse than American, British Empire, and Russian armies: remember, the victors put the defeated, not themselves, on trial….and the victors & their postwar collaborators write the history books.

That has always been factually incorrect. The first books in the western history canon were written by Herododus and Thucydides. Both were generals in the losing Athenian army. Numerous German generals wrote post-war books. Start with Guderian.

I think there is an error in the Paul Hausser bio paragraph where it states, “he retired as a lieutenant general in 1931 at the age of 51 after 40 years of service”. If he retired at 51 after 40 years of service that makes Paul Hausser 11 years old when he joined the Army. More likely he retired after 30 years service.