By Arnold Blumberg

In their directive to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) in northwestern Europe, the Allied Combined Chiefs of Staff ordered Allied forces to land in France in June 1944, break out of Normandy, and mount an offensive “aimed at the heart of Germany and the destruction of her armed forces.”

To this end, Allied planners designated the first major target inside the Reich to be the Ruhr industrial region, an area of vital economic importance. An offensive against the Ruhr would compel the Germans to commit their remaining forces so that the Allies might bring them to battle and destroy them.

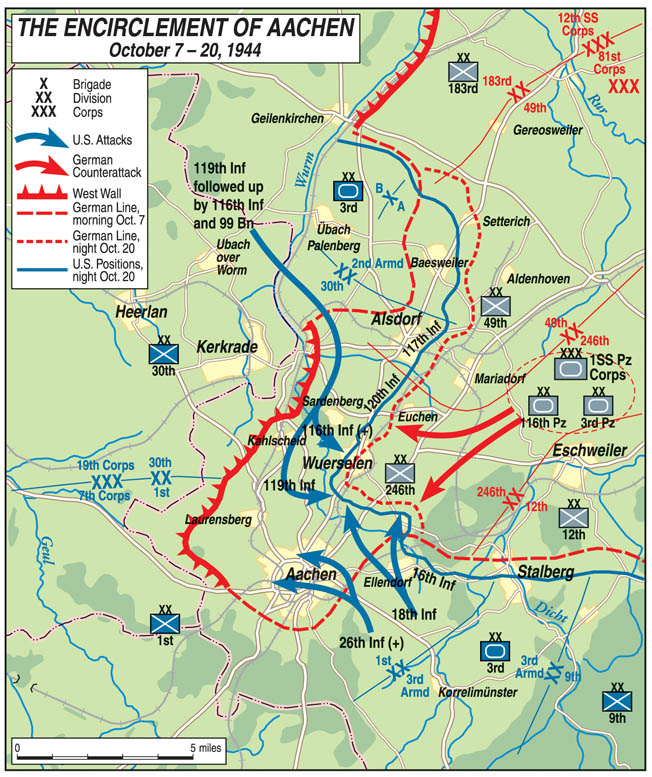

There were four major approaches to the Ruhr from France: the Plain of Flanders, the Ardennes Forest, the Metz-Kaiserlauten Gap, and the Maubeuge-Leige-Aachen axis north of the Ardennes. On September 5, 1944, Eisenhower chose the route the American armies would follow through the German defensive line known as the Siegfried Line or West Wall directly to the north and south of the ancient city of Aachen. Once Aachen and its environs were captured, the Allied high command envisioned a rapid advance to the Rhine and then on to the Ruhr with the end of the war in Europe soon following.

Militarily, Aachen had little to recommend it. Lying in a saucer-like depression surrounded by hills, it was not a natural fortress. This was surprising since in October 1944 the town lay between the twin bands of the Siegfried Line that split north and south of the city. To the west was the relatively thin Scharnhorst Line, while to the east and behind Aachen stood the more heavily fortified Schill Line.

Aachen itself was defended by the 246th Volksgrenadier Infantry Division commanded by Colonel Gerhard Wilck. The 246th had taken responsibility for this sector in late September 1944 from the 116th Panzer Division. North of the city were the 183rd Volksgrenadier and 4th Infantry Divisions, while to the south lay the 12th Infantry Division, collectively designated the LXXI Corps under the command of Lt. Gen. Friedrich J. Kochling.

Although the 246th Division had not engaged in any major combat within its own zone, Wilck’s troops had nevertheless been decisively weakened. In the desperate efforts to stem the American First Army’s recent breakthrough of the West Wall, Kochling had stripped his front of troops, including four of Wilck’s seven infantry battalions. The entire 404th Infantry Regiment and a battalion each of the 352nd and 689th Infantry Regiments had been attached to neighboring divisions.

On October 7, 1944, the U.S. XIX Corps entered Alsdorf, six miles north of Aachen, in an initial move to encircle the city and attack it from the rear. From there the Americans pressed southward toward Wurselen.

The prospects for keeping Aachen in German hands looked bleak, yet Kochling’s Wehrmacht superiors had not let him down completely. Their most immediate step had been to assemble an effective force to retake Alsdorf in hopes of preventing the enemy encirclement of Aachen. The main component of this force was the Schnelle (Mobile) Regiment von Fritzschen comprising three bicycle-mounted infantry battalions and an engineer company. In support was the 108th Panzer Brigade with 22 self-propelled assault guns.

Any genuine hope of denying Aachen to the Americans for an extended time lay not with the small Schnelle combat group but with a promise from Commander-in-Chief West Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt to commit his most potent theater reserves. These were the 3rd Panzergrenadier and 116th Panzer Divisions. Attaching these to the headquarters of the I SS Panzer Corps headed by General Georg Keppler, von Rundstedt intended to stabilize the front in the Aachen region. Since leaving the city in September, the 116th Panzer Division had been built up to 11,500 men but it fielded only 41 tanks out of an authorized armor force of 151 PzKpfw. IV and PzKpfw. V Panther medium tanks. Although the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division was in reality little more than a motorized infantry division, numbering 12,000 soldiers, 31 75mm antitank guns, and 38 field artillery pieces.

From October 5 to 7, Kochling waited in vain for the arrival of the promised reinforcements. They had been dispatched earlier, but disruptions by Allied air attacks on the rail lines had resulted in serious delays. In the meantime, Kochling feared Aachen would be lost. At the time, the number of German troops defending Aachen and its surrounding area was 12,000, including the reduced 246th Volksgrenadier Division, a battalion of Luftwaffe ground troops, a machine-gun fortress battalion, and a Landesschutzen Battalion, all under the command of Lt. Col. Maximilian Leyherr.

From the American viewpoint, the timing of the operation to encircle and reduce Aachen depended on the progress of the penetration of the West Wall north of the city. As soon as XIX Corps took Wurselen, three miles to the north of Aachen and behind the Siegfried Line, Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins’ VII Corps in the south was to attack from a jump-off point near the town of Eilendorf east of Aachen, seize Verlautenheide, a strongpoint in the second band of the West Wall, and connect with XIX Corps at Wurselen. With Aachen isolated, part of the VII Corps would reduce the town while XIX Corps and the rest of VII Corps drove east and northeast to the Roer River. Once the Roer was crossed, a quick thrust through the Cologne Plain would bring the U.S. First Army to the Rhine within easy striking distance of the Ruhr.

On October 7, with Alsdorf in American hands, Maj. Gen. Leland Hobbs, commander of the U.S. 30th Infantry Division, urged his XIX Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Charles H. Corlett, to order an immediate advance on Wurselen. Hobbs was confident he could join his division with those of the VII Corps in two days. With approval from Lieutenant Courtney H. Hodges, commander of the First Army, Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner’s 1st Infantry Division, VII Corps began its drive to Wurselen that afternoon.

The 1st Division’s 18th Infantry Regiment, under Colonel George H. Smith, was tasked with capturing Verlautenheide. For this job the regiment formed assault teams armed with flamethrowers, Bangalore torpedoes, and pole and satchel explosive charges to eliminate the German pillboxes guarding the objective. In support of the special attack teams, a self-propelled battery of 155mm field guns and a company of tank destroyers would direct fire on the enemy defenses. Air assets and 11 batteries of artillery would soften up Verlautenheide before the infantry went in. The division’s other two regiments were to aid the attack by making feints on their respective fronts. Once the town was captured, a company of tanks would join the infantry there.

Because the American attacks were confined to a combined front of only five miles, German shelling inflicted significant losses. However, simultaneous American assaults prevented the German defenders from mounting adequate counterattacks to meet the dual threat to their positions. As a result, by October 10 the 18th Regiment had reached its final objectives, including the Aachen suburb of Haaren a mile north of the city, and had cut the two main roads into Aachen. On the same day, 1st Division captured its initial objectives and 30th Division prepared to advance southward on the jungle of factory buildings lying just outside Aachen.

The same day the Americans were closing the ring around Aachen, lead elements of the 3rd Panzergrenadier and 116th Panzer Divisions reached the town and were committed to battle. However, Field Marshal Walter Model, commander of Army Group G, which included German forces in Holland and Belgium, did not feel he could launch any serious counterattack until October 12.

On October 11, the 26th Infantry Regiment initiated an attack on Aachen while the 18th held a line from Verlautenheide to Haaren. In response, a hasty but strong German counterattack by the 3rd Panzergrenadier led by 15 PzKpfw. VI Tiger and captured American-built M4 Sherman tanks was launched on the 15th. The appearance of Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter bombers and massive American artillery fire broke up the German attack the following day.

As the 1st Division battled outside Aachen, to the north Hobbs’ 30th Division started its run from Alsdorf to Wurselen, a distance of only three miles, on October 7. For the next nine days its advance was bathed in blood. Hobbs’ path south to Wurselen was impeded by numerous pillboxes even though his division had begun its advance beyond the West Wall. In addition, Hobbs had to navigate through highly urbanized coal mining country filled with slag piles, mine shafts, and villages all well suited for defense.

Further, on several occasions the Germans threatened the American advance. The first attempt was a move on Alsdorf by the 108th Panzer Brigade and the von Fritzschen Regiment against the division’s eastern flank on October 8. This effort was foiled by the American 743rd Tank Battalion, which drove the enemy out of Alsdorf after the Germans lost several tanks. On the 11th the “Old Hickory Division” clashed with the 108th Panzer Brigade again and stopped this second German counterattack, clearing the road to Wurselen with the aid of air strikes.

The following day the Nazis showed they still had fight left in them when they once more attacked the 30th Division. This drive was spearheaded by the 108th Panzer Brigade and supported by the newly arrived 60th Panzergrenadier Regiment and Kampfgruppe Diefenthal. After an all-day contest, the American line remained intact thanks in large measure to massive air and artillery support. However, Hobbs had suffered more than 2,000 casualties in six days of heavy fighting. He felt compelled to call for assistance in closing the gap around Aachen.

Reinforced with the 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Division and a battalion of Sherman tanks from the 2nd Armored Division, Hobbs’ men had battled their way by October 16 to Hill 194 on the southern fringe of Wurselen, 1,000 yards from the advance positions of the 1st Division’s 18th Regiment. The Aachen gap was finally closed.

When the American encirclement of Aachen began on October 7, the city was already a scarred shell. Of a prewar population of 165,000 souls, less than 20,000 remained there. By early October 1944, a number of Royal Air Force bombing raids had reduced Aachen to a sea of rubble. Few of its inhabitants could have doubted that the end was near when on October 10 the Americans delivered an ultimatum to the garrison commander to surrender. Dutifully, Lt. Col. Leyherr rejected the demand in accord with Hitler’s “last stand” order. Two days later, Wilck took over as the city’s military commander and established his headquarters in the Palast-Hotel Quellenhof in Farwick Park in the northern part of the town.

To storm Aachen proper, Huebner had only two infantry battalions of his 26th Regiment—less than 1,100 combat infantrymen under Colonel John F.R. Seitz. The rest of the division was spread out elsewhere along the front, and one additional battalion was his only reserve. Within the inner city defenses Wilck had 5,000 men, most of them from his division, as well as 200 police officers under arms. His armor strength was only five PzKpfw. IV tanks. The artillery consisted of eight 75mm, 19 105mm, and six 150mm guns. As long as he could communicate with the outside, Wilck could receive substantial additional artillery firepower.

General Huebner planned to cautiously attack Aachen because American positions at Wurselen and Haaren were so thinly held that German reinforcements from outside the city might break into the town from the northeast. As a divisional staff member put it, the 26th would have to attack “with one eye cocked over its right shoulder.” Yet in striking from the east through Aachen’s back door, the regiment had a distinct advantage since the German defenses in that area were understandably the weakest.

Prior to its attack on Aachen, the 26th Regiment had been chewing away at the eastern suburb of Rothe Erde. To reduce the regiment’s frontage, Seitz placed a provisional infantry company on his left facing the city and tied into the defenses of the 1106th Engineer Battalion positioned south of Aachen. Although the engineers were to keep contact with the attacking force, they were not equipped to participate in the assault. That attack was to be led by the 2nd Battalion, 26th Regiment under Lt. Col. Derrill M. Daniel. Its starting point was the ruins of Rothe Erde, and the battalion was to move westward through the heart of the city. The 26th’s 3rd Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. John T. Corley, stationed between Rothe Erde and Haaren, was ordered to attack north and west, take the factory district lying between Aachen and Haaren, and then move west to seize three hills dominating Aachen on the city’s northern edge. The bulk of the hill mass 3rd Battalion was to capture had been made into a public park known as the Lousberg. The high ground rose 862 feet and cast a shadow over the entire city. To the Americans it was known as Observatory Hill after an observation tower on its crest. A lower knob on the southeastern slopes of the hill was crowned by a cathedral and is called the Salvatorberg. Down the southeastern slope in Farwick Park stood the Palast-Hotel Quellenhof.

On October 11, the IX U.S. Tactical Air Force dropped 62 tons of bombs on the outer perimeter of Aachen. Twelve artillery battalions of the 1st Division and VII Corps then unleashed 4,900 rounds on the town. After the fire fell silent, American patrols entering still encountered strong enemy fire. Over the next two days more air raids were conducted, and another 5,000 artillery shells hit the town.

By nightfall on October 12, the 3rd Battalion had cleared the industrial area between Aachen and Haaren in preparation for the main assault. Moving through the center of Aachen on a 2,000-yard front, Daniels’ men had to plow through the maze of rubble and damaged buildings in their path and maintain contact with Corley’s command.

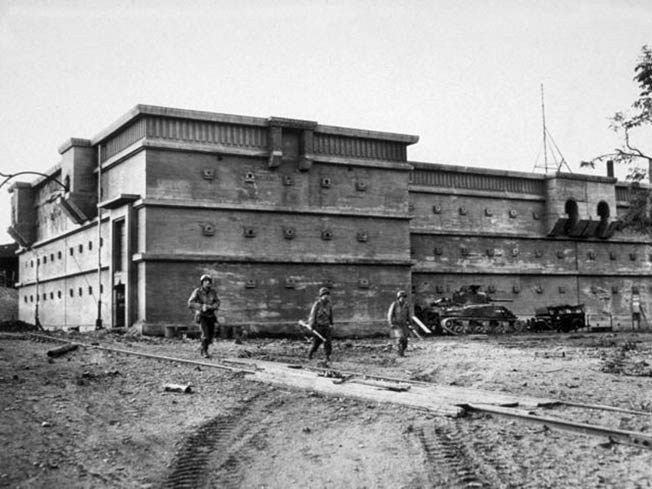

Dividing his men into small assault teams, Daniels sent one tank or tank destroyer with each platoon. The armor would keep the buildings under fire until the accompanying riflemen made their assault; the armor would then shift its fire to the next building. Augmented by light and heavy machine-gun fire from the streets, the tank shelling drove the German defenders into the cellars where the American soldiers would then attack using hand grenades. When they met strong resistance, the Americans used demolition charges and flamethrowers handled by two-man teams attached to each company. The men did not wait for actual targets to appear; they assumed each building held hostile forces. Light artillery and mortar fire swept forward several streets ahead of the infantry, while heavier artillery pummeled German positions farther to the rear.

To maintain contact between his units, each day Daniels designated a series of checkpoints based on street intersections and prominent buildings. No unit was to advance beyond a checkpoint until it had established contact with an adjacent unit. Each rifle company was given a specific site to advance to; company commanders in turn designated a street to each of their platoons. After a few bitter experiences of Germans bypassed in cellars and sewers emerging to attack the GIs from behind, the Americans learned that firepower and deliberate progress were more important than speed.

In the other half of the attack, Colonel Corley’s battalion driving west toward the high ground on Observatory Hill found its route blocked on the first day by stoutly defended blocks of apartment buildings. The men measured their gains in buildings, floors, and even rooms. Someone said after the battle that the fight was “from attic to attic and sewer to sewer.” As riflemen from Company K advanced down Julicher Strasse, a 20mm cannon opened fire from a side street, driving them back. Two American tanks were then knocked out by Panzerfaust shots. One of the steel monsters was remanded by Company K’s Sergeant Alvin R. Wise, who began to spray adjacent structures with the tank’s machine guns. He and two buddies got the engine started and drove the vehicle to safety.

Having discovered that some buildings and air raid shelters could withstand tank and tank destroyer fire, Corley called for 155mm self-propelled artillery support. The next morning the big weapons proved their worth by devastating a strongly built house. Impressed, the regimental commander sent one of these artillery pieces to his other battalion.

By nightfall on the first day, Corley’s men had reached the base of the Lousberg. The next day, October 14, a rifle company was able to reach Farwick Park. Yet the American hold on that objective was tenuous at best since the rest of the battalion was hung up battling defenders holed up in structures approaching the park. The Germans still held the hotel, the Kurhaus, the Orangerie greenhouse, and several garden buildings.

As early as October 13, Wilck had asked for reinforcements. That night 150 men from the 404th Infantry Regiment strengthened the defenses on Observatory Hill. SS Battalion Rink, part of Kampfgruppe Diefenthal, attempted to join the defenders but was sidetracked by an attack on Wurselen by the 30th Division. The next day, Kochling was able to slip eight assault guns into the city to help the garrison. On the 15th, SS Battalion Rink finally entered the town.

On the same day, Colonel Corley renewed his attack on Farwick Park. By noon, under cover of a mortar barrage, his men had wrested control of the garden buildings and the greenhouse from the enemy but were unable to capture the Hotel Quellenhof. Just as the colonel sent a company supported by a 155mm gun to flank the hotel, the Germans launched a counterattack. Made up of the remains of the 404th Regiment and SS Battalion Rink, the Nazi blow was parried by the an infantry company occupying the north edge of Farwick Park. The fight continued for an hour before the Americans had to fall back from the enemy advance, which was supported by several assault guns. By 5 pm, the steam had run out of the German attack.

As Corley’s men stopped the German attack near Farwick Park, Huebner postponed any renewed advance in Aachen, even as Corley confidently proposed the opposite course of action. The reason for the division commander’s reticence was the punishing blows the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division had been administering to the U.S. 16th Infantry Regiment near Eilendorf. He ordered Colonel Seitz to hold in place until the situation along the division’s eastern wing was stabilized. As it turned out, Huebner’s stay of any offensive action in Aachen lasted only a day. By October 16, the 16th Infantry Regiment had repulsed the efforts of the 3rd Panzergrenadiers to break the American line. Further, the long-awaited juncture between the 1st and 30th Infantry Divisions, which finally closed the Wurselen gap north of Aachen, allayed the American general’s concern for the safety of his southeastern flank. Huebner still held back the 26th Infantry Regiment for another 24 hours while he awaited the arrival of reinforcements from VII Corps before continuing the fight for Aachen.

General Collins had decided to reinforce the two battalions—one of tanks and the other of armored infantry from the U.S. 3rd Armored Division—that had been readied to counterattack any enemy penetration at Eilendorf. Thanks to the stiff defense put up by the 16th Infantry Regiment, this force, called Task Force Hogan, was no longer needed at Eilendorf. As a result, it was sent to fight on the north flank of Corley’s unit, launching a right hook against the Lousberg. Part of Task Force Hogan’s armor was also to occupy the village of Luarensberg, a key to the West Wall defenses north and west of Aachen and still in the hands of the depleted German 49th Infantry Division. In addition, General Collins attached to the 1st Division a battalion of the 110th Infantry Regiment, 28th Infantry Division. Huebner was to use this battalion strictly defensively to cover the growing gap between Daniels’ unit and the 1106th Engineer Battalion located south of Aachen. On October 18, with all the American forces in place, the 1st Division’s commander ordered his men to renew their attack on Aachen. At that time the German garrison had only 4,392 combat effectives.

In Farwick Park, Colonel Corley’s formation set out to regain the ground it had lost three days before, pass onto Observatory Hill, and help Task Force Hogan’s drive on the rest of the Lousberg. One platoon quickly recaptured the Kurhaus. While the enemy sheltered from an American artillery barrage in the hotel basement, a platoon under 2nd Lt. William D. Ratchford stormed into the hotel lobby. Hand grenade duels erupted at every entrance to the basement. With the threat of machine-gun fire directed at them, the Germans surrendered. Twenty-five defenders had died in the fight for the hotel. A search of the building revealed large caches food and ammunition, as well as a 20mm antiaircraft gun sited on the second floor.

With Farwick Park and its buildings firmly in American hands, Daniels’ men set course on a methodical sweep through the center of the city. On the 19th Corley’s troops captured Observatory Hill against light opposition as Task Force Hogan overran the heights of the Lousberg. Because the 30th Division had already occupied the village of Laurenberg, Huebner directed Task Force Hogan to sever the Aachen-Laurensberg highway a short distance from the village. By nightfall on the 19th, part of the task force had taken a chateau 200 yards from the road.

Meanwhile, in a written proclamation Colonel Wilck exhorted his command to “fight to the last man.” However, exhortations would do little to alter the city’s fate. By the end of October 19, the German high command had decided to withdraw. The headquarters of the 1st SS Panzer Corps was ordered to suspend any offensive actions to relieve Aachen, and the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division, down to half its original strength, was instructed to prepare to leave the Aachen front.

On October 19-20, resistance in Aachen rapidly crumbled as Daniels’ battalion, along with elements of the 110th Infantry Regiment, eviscerated the town. Soon Daniels and company cut off the residential section of the city from its western environs. The next day Colonel Corley’s battalion reached a large air raid bunker near Lousberg Strasse. Unknown to the GIs, this was Colonel Wilck’s command post. As Corley called up his 155mm self-propelled gun and used it to pump a few shells into the shelter, Wilck decided to end the fight for Aachen.

Using 30 American prisoners as go-betweens, Wilck requested they arrange the surrender of his garrison. Two members of the 1106th Engineer Battalion, who had been taken captive by the Germans in the early fighting for Aachen, and two German officers dashed into Lousberg Strasse as small-arms fire cracked around them. When American soldiers entered the bunker, Wilck and his staff had already packed their bags and were ready to go. As the Germans left the bunker, Staff Sergeant Ewart M. Padget, one of the former prisoners from the 1106th Engineers, nabbed the prize souvenir of the occasion, Colonel Wilck’s service pistol.

At Corley’s headquarters, the 1st Division’s assistant commander, Brig. Gen. George A. Taylor, accepted the German surrender, and at 12:05 pm on October 21 it was all over. By nightfall the Americans had completed a sweep of the entire city, rounding up 1,600 German soldiers.

The end of the battle for Aachen witnessed a city, as one America observer later wrote, “as dead as a Roman ruin, but unlike a ruin it has none of the grace of gradual decay…. Burst sewers, broken gas mains and dead animals have raised an almost overpowering smell in many parts of the city. The streets are paved with shattered glass; telephone, electric light and trolley cables are dangling and netted together everywhere, and in many areas wrecked cars, trucks, armored vehicles and guns litter the streets….” Fully 80 percent of the city had been destroyed by a combination of RAF bombing and American shellfire.

Although the Germans had failed to prevent Aachen’s encirclement and held out for only five days after it was surrounded by the Americans, the real measure of the fight from their standpoint was the telling cost to the Germans. The 30th Division took 6,000 German prisoners, the 1st Division another 5,637, including 3,473 captured within the city. The way the Wehrmacht units were squandered in the fight without any major achievement was indicated by the fact than an equivalent of 20 battalions had been used in counterattacks against the 30th Division. Yet in only a few instances had any of these involved more than two reinforced infantry battalions. A never ending compulsion to stave off possible future crises had sucked the defenders into the abyss of piecemeal commitment of their forces.

On the American side, the Old Hickory Division and its attached units had lost 3,100 men since the start of the West Wall Campaign on October 2, 1944. The Big Red One sustained 498 casualties from the two battalions of the 26th Infantry Regiment. Of these, 75 were killed and nine missing. With these divisions depleted and exhausted, Hodges and his boss, General Omar Bradley, commander of the American 12th Army Group, believed the U.S. First Army had to be reinforced before it could take offensive action again.

This was the achievement of the doomed German defense of Aachen.

Arnold Blumberg is an attorney with the Maryland state government and resides with his wife in Baltimore County, Maryland.

A lot of people died.