By Phil Zimmer

The tennis-shoed soldiers emerged from the darkness on July 6, 1953, like a “moving carpet of yelling, howling men [with] whistles and bugles blowing, their officers screaming, driving their men” against the Americans as they swept up Pork Chop Hill (Hill 255), recalled Private Angelo Palermo.

The lead elements of the Chinese infantry were loaded down with grenades, but they carried no rifles or submachine guns in their assault on the nondescript hill made famous by the 1959 film Pork Chop Hill, which was based on military historian S.L.A. Marshall’s book. They were trained to pick up and expertly use weapons dropped by their enemy as they rushed relentlessly forward like a large wave to engulf and overpower everything before them. Palermo and his U.S. Army buddies in Company A were outnumbered four or five to one by the Chinese assaulting the Americans’ recently shored-up trenches.

The Chinese knew what they were doing and were determined to advance over the covered trenches separating the 1st and 2nd Platoons and make a beeline toward the company’s command post located just east and below Pork Chop’s highest point. Near that point they would enter the open trenches and cut the defenses in half just below the two high points on the hill.

Once in the covered trenches, they could continue their rapid-fire advance to the command post and seize the secondary crest while the largest group of fighters, estimated to be a company strong, would take the hill’s crest. Two more Chinese platoons would roll over the crest, one intending to penetrate the rear and the second running to take the evacuation landing zone.

The Chinese had done their homework during the 10 weeks the Americans had taken to reconstruct Pork Chop Hill’s defenses since the failed April attempt to take the hill. The Communists under General Deng Hua, deputy commander of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army in Korea, were the experienced and well-trained 141st Division of the 47th Army and the 67th Division of the 23rd Army. The battled-hardened Chinese knew how to conduct fierce, head-on infantry assaults and were well versed in mountain warfare. They were pitted against Maj. Gen. Arthur G. Trudeau’s fairly equal-sized 7th Infantry Division of 19,000 men, which included a battalion of armor and six battalions of artillery. Both sides knew the coming battle might influence the peace discussions that appeared nearing conclusion.The Chinese knew what and where the obstacles were, and they had come well prepared with bazookas, satchel charges, automatic weapons, hand grenades, and flamethrowers. Some in the assault force even came equipped with sulfur sticks to create acrid fumes to force the Americans from their bunkers.

Private Harvey Jordan and his machine gun crew survived a direct-fire round, either from a recoilless rifle or from a Soviet-built T-34 tank, which struck an adjacent bunker, killing two Browning automatic riflemen and severely wounding their squad leader. Both heavily fortified bunkers partially collapsed as the squad leader continued to scream in pain.

As the air cleared, Jordan checked his weapon and attempted to fire at the oncoming red tide. It spit out one bullet and then the machine gun stopped, damaged by the explosion. Jordan and his South Korean ammunition bearer started throwing grenades in a desperate effort to ward off the attackers. An incoming hand grenade knocked the American across the floor, spraying him with shrapnel and wounding one eye. He was saved by his body armor, but his Korean helper lay dead. By now the Chinese were on them, spraying the bunker’s walls and floor with their burp guns from the lip of the trench before Jordan fell unconscious.

In a nearby bunker, Private George Sakasegawa and his squad leader held their fire until the oncoming Chinese tide was nearly on them. Then they let loose with everything they had as the enemy hurled grenades, one exploding near Sakasegawa and causing shrapnel wounds to his buttocks and legs. The Chinese continued forward in their saturation attack, quickly dividing and isolating the defenders on Pork Chop Hill. Simultaneous diversionary attacks were occurring at outposts Snook, Arsenal, and Arrowhead.

Company A on the right shoulder of Pork Chop Hill came under severe mortar and artillery attack as the Chinese swarmed into the trenches in the center between the two high points of the hill. That isolated the 1st and 2nd Platoons as a major force of the enemy swept over the crest toward the rear slope, heading toward Company A’s command post.

Lieutenant David Willcox of the 2nd Platoon headed out of the command post toward bunkers 53, 54, and 41, which were under heavy attack. He became separated from the two troopers with him and Willcox found himself engaged in the fight of his life. He came well prepared to the fight. He had emptied his .38 and .45 caliber pistols, killing a dozen of the enemy at close range, when another Chinese soldier came at him before he had time to reload. Willcox grabbed one of three knives he had on him and killed his opponent, who turned out to be a fresh-faced teenager.

Willcox made it to Bunker 53 and took cover there with a handful of others. Although wounded in the back, Willcox stationed himself at the bunker’s entrance where he tossed grenades at the advancing enemy. An incoming grenade wounded him in the leg. He was helped inside by his men, and they sandbagged the entrance and successfully held off repeated enemy assaults over the course of the next two and a half days.

The Americans on the hill had a difficult time fending off the enemy’s steady attacks. Several bunkers and trench systems already had been taken by the enemy in bloody hand-to-hand combat between individuals and small groups of soldiers.

Lieutenant Dick Inman of Baker Company rounded up his troopers in an effort to reach the 2nd platoon’s supply bunker near the command post where they could find a fresh supply of much-needed ammunition and grenades. The Americans fought their way along the trench, dodging enemy grenades while throwing their own and firing their weapons at close range as they advanced. They came to a stop near Bunker 54, which had been seized and was heavily defended by the Chinese. Two efforts to retake the bunker proved futile, and many of the weapons carried by Inman’s men had jammed, grenades had been depleted, and ammunition was running desperately low.

The situation was nearly beyond desperate at that point. Inman took the men with operating weapons and divided them into two groups in a continued effort to get through to the supply bunker. Two men, one armed with a Browning Automatic Rifle, were to run on the upper side of the trench to lay down covering fire as they ran past Bunker 54. Inman, with a carbine in hand, and a soldier with a rifle were to make a similar dash along the lower side of the trench.

The Chinese had other thoughts. Their heavy fire injured and forced the two men back from the upper side. Inman, on the other lip of the trench, took a round to the head. Sergeant Alfredo Pera and Corporal Harm Tipton made a fateful decision to retrieve Inman under fire and carry him toward safety. An enemy grenade exploded, wounded both rescuers, and forced them to leave the mortally wounded Inman behind as they staggered dazed and wounded downhill to a supply point where they were treated and evacuated.

For the men on the hill, the Chinese kept coming, isolating them from their units and leaving them in a desperate struggle often with jammed weapons or no ammunition. Men on both sides often resorted to knives or fists in the swirling, confusing melee on the darkened hill. Communication with the outside world was often impossible because of damaged radios, cut field telephone lines, and heavy rain that shorted out equipment.

American soldiers yelled at each other to take cover because U.S. artillery fire with proximity fuse shells had been called on the position. This kind of artillery fuse was set to explode in deadly air bursts above the fighting, covering the area with red-hot shrapnel. Only those in the bunkers or covered trenches would survive this type of artillery shell, which was coupled with a close-in curtain of fire around Pork Chop to protect the defenders from additional waves of incoming Chinese troops.

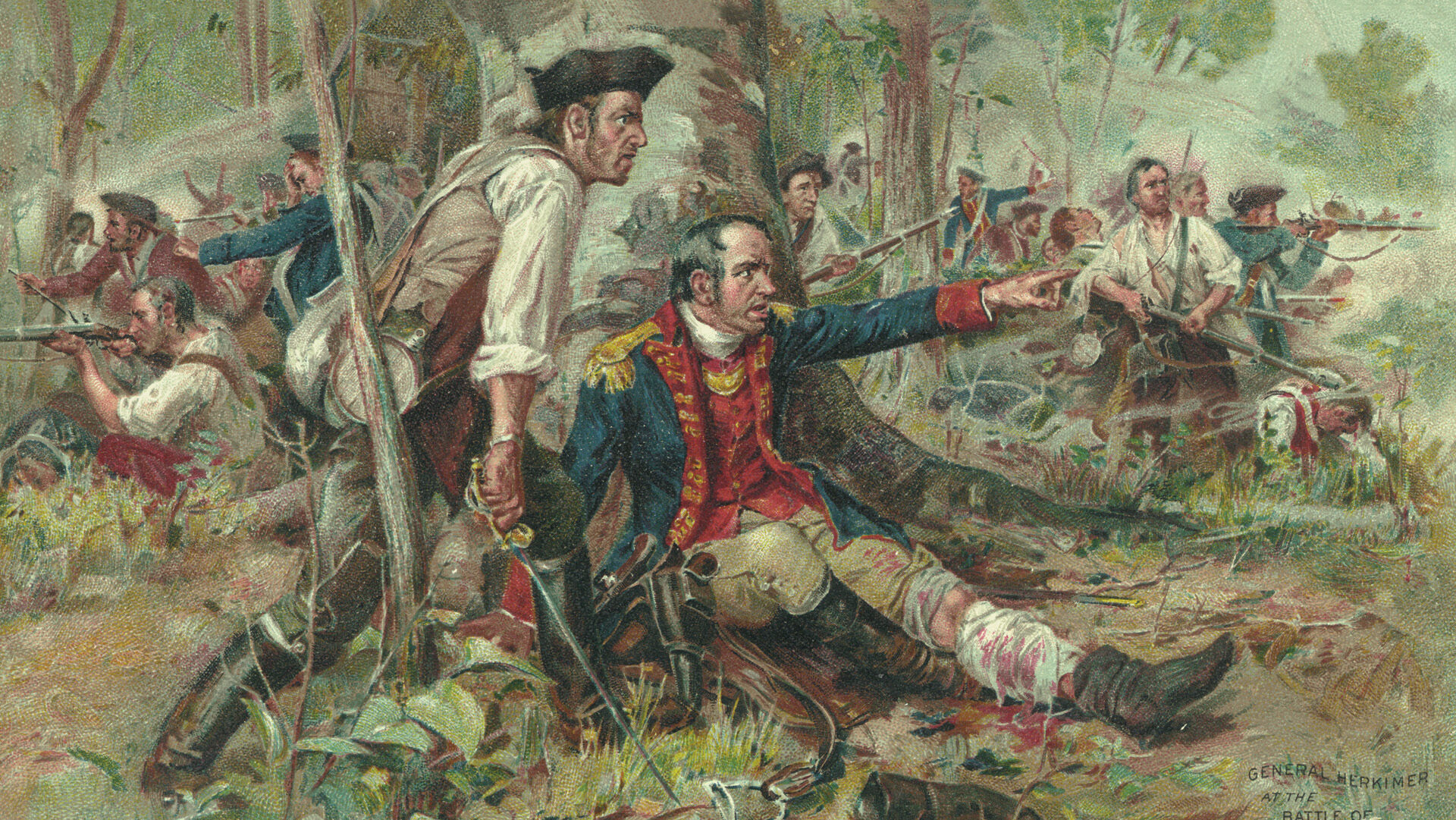

The bitter struggle over Pork Chop Hill was part of a larger effort of the so-called Battles of the Outposts that ran roughly from July 1951 until the armistice that halted the fighting in the Korean War was finally signed in late July 1953. This was a comparatively static phase of the war with bitter regiment-sized or battalion-sized attacks limited in scope by key tactical terrain along a front that had been stabilized north of Seoul.

During the Battles of the Outposts, both sides maintained sizable opposing forces behind their outposts and along their respective main lines. The extensive use of heavy artillery and mortar barrages was reminiscent of World War I, and the relatively static situation stood in sharp contrast to the first year of the war, which had been characterized by the sudden sweep southward by the North Koreans followed by the push north to the Yalu River by U.S. and United Nations forces and the enemy’s subsequent push southward with the assistance of the Red Chinese.

The outpost battles, including the struggle for Pork Chop Hill, were often exceptionally fierce and bloody with nearly half of America’s 140,000 casualties occurring during that time period. The heavy fighting was fostered, in part, by an earlier understanding that the peace line would be drawn along the fighting line when the final agreement took effect.

In the fighting that occurred on Pork Chop Hill in mid-April 1953, hundreds of Chinese were killed and thousands wounded in a failed attempt to take the hill. Seventy-three Americans lost their lives during the two-day battle in April that did not draw much attention, probably in part because it was largely an artillery duel between the two sides.

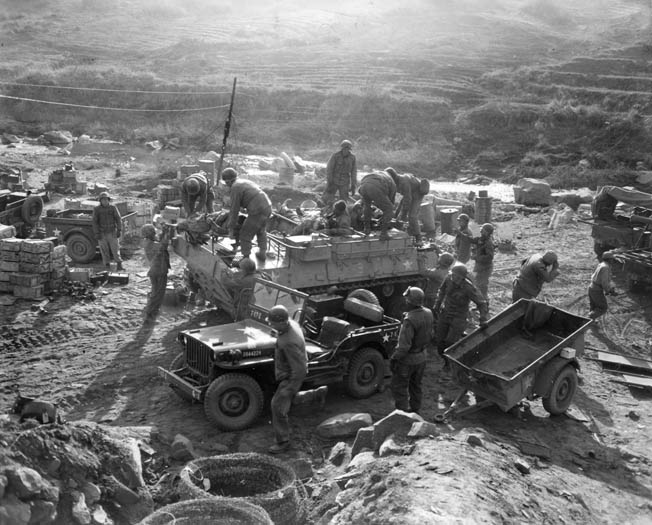

Following that successful defense, American engineers and others were brought in to reinforce the bunkers and strengthen the trenches on Pork Chop Hill. One of the men, Private James Reardon, was called in to help manhandle large ammunition crates into position in the deepened bunker system. The work took its toll on the men, including Reardon, who suffered triple hernias and was evacuated to Japan for a painful round of operations. That may have saved his life because he missed the far more deadly July battles on Pork Chop Hill and only managed to return to Korea after the armistice.

The Chinese meant business in the July 6 attack. Despite the proximity fuse artillery fire throughout the night, nothing stopped the determined offensive. By 11 pm, only minutes after the initial attack, the enemy fire was striking the evacuation point near Able Company’s command post and its supplies. The Chinese had reached the rear of the defensive system, temporarily cutting off Pork Chop from friendly forces. Within another few minutes the enemy was around the command post and on the crest of the hill above it.

The determined Americans fought on, sometimes singly and at other points in small groups. Master Sergeant Howard Hovey, a World War II veteran who was soon to go home to retirement, ran to the trenches near Able Company’s command post to direct fire against the oncoming Chinese. Hovey twice left the relative safety of the trenches to use his carbine and grenades to turn back the enemy before dying under fire. His aggressive actions enabled the Americans to evacuate the command post and set up another one near the evacuation landing zone.

Although attacks occurred all along the Americans’ main lines that night, the focus was clearly on Pork Chop Hill. Fortunately, Baker Company had been kept in reserve nearby and was called into action shortly after 11 pm to reinforce Company A. Despite the noise and artillery, the troopers coming to the rescue had no idea how desperate the situation was on the hill.

Company B approached the rear slope and fought onto the hill by 12:30 am but at first was not able to make contact with the men of Company A who were close enough to see the Chinese silhouetted on the crest against the flame-lit sky as the enemy worked feverishly to gain control of the trench and bunker system.

Company B commander Lieutenant William J. Allison, unaware of the enemy’s approach from the west and their seizure of the hill’s east crest, ordered an immediate attack. Meanwhile, American artillery continued to lash the hill with fierce curtains of fire while sending counterbattery fire on Chinese artillery and mortar positions. Allison and his men had marched into the jaws of death that would grip them and the others over the course of the next grueling, life-threatening 40 hours.

Allison learned that the Chinese had taken the crucial trench between the two sectors of the American defense system on Pork Chop Hill. Ordering his men forward up the hill, he could see the enemy sweeping over the crest from the back portion of the hill. They put heavy fire on the Chinese, but as their ammunition diminished he ordered the men in his company back to hold the main supply bunker. They used their time wisely, caring for the wounded and resupplying themselves with ammunition just before Allison was struck and killed by a sniper’s bullet.

Company B eventually made contact that night with Company A as they fought to regain bunkers held by the Chinese. By 3:30 am on July 7, they were calling for reinforcements to man the bunkers that had been cleared of the enemy. A bit later the company swept over the hill, retook eight or nine bunkers on the left sector, and cleared the central part near Company A.

The Chinese still held a good hand; they commanded three bunkers on the rear slope in the right sector and were in good position to rake the evacuation area and the access road with heavy machine-gun fire. Acting platoon leader Tony Cicak safely threaded his way from the trenches down to the access road, took temporary command of an American T-18 armor personnel carrier with its mounted .50-caliber machine gun, and directed it toward the Chinese guns. He managed to fire off three or four rounds before the gun jammed and the crew hurriedly backed the vehicle from the scene.

Company E had been on standby, and shortly after 4 am on July 7, its first platoon had arrived on the hill. They reported that more infantrymen were needed to hold the cleared bunkers and to evacuate the dead and wounded. Once that was accomplished, the remainder of Company E reinforced the hill by 5:30 pm.

The battle for the hill became, in many respects, a campaign dominated by artillery, mortar fire, and tactical air strikes. Within the first few hours of the July 6 attack, the enemy had lobbed approximately 20,000 artillery rounds onto Pork Chop and the surrounding hills. Not to be outdone, U.N. forces resorted to similar weapons along with tank and recoilless rifle fire, antiaircraft weapons, and lead poring forth from quad .50-caliber machine guns.

The Chinese held the higher ground around Pork Chop Hill and could drop fairly precise heavy fire on the besieged hill and its environs. And once they had gained the hill’s crest, the enemy artillery and mortar rounds became even more deadly for the Americans. The Chinese were not averse to raining heavy fire down on their own soldiers if their positions were on the verge of being retaken by determined American troops.

The Chinese had learned Soviet maskirovka, or deception tactics, used effectively in World War II against the Germans. They employed extensive camouflage and night movement and rolled artillery back into deep and well-hidden caves after firing. Much of their artillery and other heavy equipment had been brought south over Soviet-designed invisible bridges, constructed so the bridge surface was approximately one foot below the water so that it could not be spotted by U.N. aircraft.

The heavy artillery and mortar pounding contributed to the turmoil on Pork Chop Hill. Gravely wounded and dying men from both sides littered the hillside while small groups of men struggled for survival in hand-to-hand combat on the exposed, rain-swept terrain and in the covered trenches and bunkers. Some of the wounded Americans moved to the evacuation landing during lulls in the fighting. On the desperate east shoulder of the hill, the injured huddled together, often cut off from the others, pinned down by Chinese snipers.

Early on the morning of July 7, Lieutenant Dick Shea, Company A’s acting commander, was in the trenches when Chinese soldiers rushed forward, seemingly out of nowhere. He shot down four or five of the enemy, and when he ran out of ammunition pulled his knife, killing two more of the attackers, causing the others to flee. He rallied his men and led them down the trench line, forcing the Chinese back even farther. Their courageous efforts netted the defenders a better view of enemy-held areas and improved fields of fire.

Reinforcements came that morning with the arrival of Lt. Col. Rocky Read, 1st Battalion commander, and a platoon from Company E, which set up a command post in reinforced, two-room Bunker 45, located on the hill’s reverse slope.

The remainder of Company E was brought up as the dead and wounded were taken from the hill. Lieutenant Macpherson Connor’s platoon was assigned to hold the engineers’ tunnel, Pork Chop Hill’s crucial main trench. A series of trenches radiated from the tunnel, and there were vertical shafts leading topside where the Americans could hear Chinese voices. Connor and his men desperately set about reinforcing the tunnel, using sandbags to block trenches that had been taken by the Chinese. They also dug recessed positions along the tunnel walls in case the enemy gained access and started firing down the trench line.

At noon the Chinese made a bold attempt against the north end of the tunnel and were forced back by Connor’s men. He rallied his troopers and counterattacked to drive the Chinese away from the command post. The fighting was chaotic and confusing with the Americans holding the eastern and part of the central sector while the Chinese tightened their grip on the western sector. The Americans did retake several bunkers but could advance no farther without additional men.

Hand-to-hand fighting continued throughout the day as both sides filtered reinforcements onto the hill. The armored personnel carriers continued to resupply the hill and evacuate the wounded. Lt. Gen. Arthur Trudeau arrived for a personal look around noon on July 7 and came away convinced the hill could be held if the men received additional ammunition and communications equipment.

Rather than face a daytime counterattack in full view of enemy observation and artillery, the Americans opted for a surprise nighttime attack to sweep the Chinese from the bunkers on the highest points of the hill. The enemy had plans of its own and at dusk attacked nearby Hill 200 and the evacuation landing zone, using the attacks as diversions as they worked to reinforce their position atop Pork Chop Hill.

The Americans previously had made plans for the men on Pork Chop Hill to take part in a counterattack that would be supported by the 32nd Infantry’s Company F. The latter would sweep down from nearby Hill 347, cross the valley with its swollen, waist-deep stream, and then work its way up the south slope of Pork Chop Hill in the surprise counterattack to retake the hill’s crest. It would be an exceptionally dangerous nighttime effort, with Fox Company crossing unfamiliar wet and steep terrain, but the audacity itself would add to the surprise. The night of July 7-8 would prove to be a very long one for those men.

As Company F reached the hill and started to move upward, the Chinese worked to infiltrate the American positions from atop Pork Chop Hill, getting on top of the American-held bunkers and tossing hand grenades inside. Exhausted from slogging five hours to reach the western trenches, Company F, still undetected, then received new orders. It was to sweep and seize Pork Chop Hill’s crest. The Chinese fought back furiously, throwing grenades, mortars, and artillery at the advancing Americans. A second Chinese battalion reinforced existing units throughout the night.

Fox Company regained some trenches but was not able to force the determined Chinese from their fiercely held positions at the crest. Company F was ordered to pull back at 4:25 am July 8 and fight toward the evacuation landing zone, taking its wounded along under exceptionally heavy enemy artillery fire. Upward of five enemy artillery rounds per second were striking near the crest at that point, according to one American officer.

Against tremendous odds, the remnants of Company F dodged the artillery and enemy hand grenades to make it off the hill safely. Armored personnel carriers loaded with wounded took them to a collection point behind Hill 200. One injured trooper made it off the hill using his arms and one good leg to move slowly backward down the hill. Another reported seeing an American standing shell shocked near the stream with both eyes blown from the sockets and dangling on his cheeks.

Fox Company’s failed attack did manage to foil the Chinese effort to take the crucial evacuation landing zone and its connecting road. That would have isolated the defenders of Pork Chop Hill and prevented them from receiving badly needed ammunition, supplies, and reinforcements. The 13th Engineers, in a little noted heroic effort, managed to keep the supply road open with a 60-foot long Bailey bridge constructed and put in place at night over the swollen stream despite significant enemy opposition.

The Americans now recognized that it would take more than a solitary rifle company to reinforce and fully retake Port Chop Hill, which stood in the way of a Chinese breakthrough to the American main lines. Plans were quickly made for a two-company daytime counterattack shortly before 4 pm on July 8.

It would be a rather complicated combined attack preceded by heavy artillery and mortar fire to dampen resistance and knock out enemy mortar and artillery positions. Company G of the 2nd Battalion was to take the high ground on the east side of Pork Chop and Company E was to follow the streambed, attack up the western side of Pork Chop, and link up with Company G on the hill’s high ground. Plans were also made to remove Companies A and B from the hill before the attack.

The situation on the hill was confusing with American and Chinese troops intermixed in the dense warren of bunkers; each side was struggling to ward off attacks and maintain their tenuous hold on the hill. The Chinese continued to possess the high ground near the crest, lobbing hand grenades and directing automatic weapons fire on anything that moved their way.

By mid-afternoon, Company E had moved into position and relieved the two companies that then vacated the hill. Company G moved downward from Hill 200 and toward the back slope of Pork Chop Hill, where it planned to consolidate on the hill and attack west. Ideally, the two companies would link up once the Chinese were swept from the crest and cleared from the bunkers and trenches.

The fighting became reminiscent of World War I. Company G went over the top of the trench and started toward Pork Chop as enemy machine-gun fire cut down the advancing troops. The shellfire was intense on both sides as the men made their way through the barbed wire on their way toward Pork Chop Hill. Chinese observers on the higher surrounding hills continued to call down artillery and mortar rounds on the advancing Americans.

Those who made it that far started climbing the hill, heavily loaded with equipment and ammunition, as the incoming fire further intensified. They were forced to move west through the trench line, caved in in many places by the heavy artillery fire. It was a grisly scene with American proximity fuse shells exploding above them as they crawled along the trenches, littered in many places with several layers of the dead.

Men all over the hill had become separated from each other and their leaders as the struggle degenerated into small insolated groups desperately fighting similarly struggling groups of the enemy. The bunkers presented difficulties as well; those held by the Chinese were well manned and bristling with machine guns. The bunkers were well built, too, and the incoming artillery and mortar fire made it difficult for American sappers to get near those held by the enemy.

Corporal Dan Schoonover, a demolitions specialist in Company A’s 13th Engineers, overpowered one Chinese-held bunker by dashing forward, hurling grenades into an aperture, and then running to the doorway and emptying his pistol to silence the opposition. Despite all efforts on the part of the two companies, the attack had stalled by 6 pm. Company G had suffered the loss of most of its officers and nearly half its enlisted men with the survivors isolated and largely leaderless on the battlefield.

Company A’s 2nd Platoon remained isolated and bone weary after nearly 44 hours of fighting on Pork Chop Hill. And nearly 80 percent of those able to fight were wounded to boot. Shea realized those men could not be rescued unless Company G’s survivors rallied and took the pressure off the beleaguered platoon. He swung into action and led a number of successful attacks to take the pressure off the 2nd Platoon. As daylight approached on July 9, Shea led a bold attack from above the trenches to force the Chinese from the bunkers and trenches they had seized.

As he and his men rushed forward the Chinese repositioned for the counterattack and overwhelmed Shea and his exposed men. The Chinese continued to infiltrate, reinforced their positions, and apparently prepared to launch a counterattack of their own. And the Americans were laying plans to launch Company F of the 17th into the battle at 1 pm on July 8 to reinforce the elements already in place on the hill. The Chinese relished shelling the fresh troops during their four-hour march toward the hill, causing 40 casualties. The Americans climbed aboard armored personnel carriers for the final run at 6 pm to Pork Chop Hill. The Chinese responded quickly to the assault on the south side of the hill, welcoming the intruders with a hail of grenades and machine-gun fire.

Despite the fireworks, the Americans advanced and took a crucial bunker before reaching the crest. Ammunition was running low as dusk fell and the Americans could see additional enemy fighters coming over the north slope, lobbing hand grenades as they advanced. The remnants of Fox Company formed a defensive perimeter and remained in place until morning when they were ordered off the hill.

The Americans were not done yet and had already laid plans for another counterattack by the 3rd Battalion’s 17th Regiment. The plan called for the unit’s Companies K and I to attack south to north over Pork Chop’s crest. The Chinese struck first, creating further havoc on the hill for Companies E and G still positioned there. The Chinese moved forward, battalions strong on the west shoulder of the hill during the evening of July 8, despite the combined heavy artillery, mortar, and small arms fire from the Americans.

Over the next several hours of darkness, the area became a living hell for everyone on the hill. Friendly and enemy forces were intermixed on Pork Chop Hill as both the Americans and Chinese pummeled the hill with heavy artillery and mortar fire. The Chinese continued to heavily reinforce the hill, burrowed deeper into the terrain for cover, cut or jammed American communications, lobbed hand grenades into the covered American trenches, and infiltrated snipers into the rear. All the while the enemy continued to maintain its strong grip on the north slopes and Pork Chop’s crest throughout the night of July 8-9.

Throughout this stage of the battle, the American commanders were faced with trying to figure out how best to bring additional men into the battle without weakening the main line positions located behind Pork Chop Hill. Causalities were climbing and ammunition was running low, creating logistical difficulties for the Americans at both aid stations and resupply points.

Company K started for Pork Chop at 3 am July 9, headed toward the east shoulder of the hill, followed shortly thereafter by Company I, headed farther west to assist Fox and Easy Companies. The Chinese spotted the advance and brought intense artillery and mortar fire down on the exposed Americans. They made it to their positions on the hill. Heavy fighting renewed at sunrise as the combined American units made an effort to force the heavily defended and determined Chinese from the hill’s crest. That effort, too, came to naught when the enemy inflicted heavy causalities on the advancing Americans. Those on the scene noted that by this time the American bodies were lined up like cordwood at the evacuation zone, awaiting a final ride from the fighting.

The American commanders, observing the battle from afar, believed that bringing an additional company to bear might break the will of the Chinese atop the hill, who had faced three solid days of close-in fighting and heavy pounding from American artillery and mortar fire. These additional Americans made little impact in the face of continued Chinese reinforcement and renewed attacks, and the night of July 9-10 was little different than those that came before. The Americans remained on the hill, isolated in the dark, struggling moment to moment to remain alive in the hell of the artillery and deadly fighting that engulfed them.

Early on the morning of July 10, the call went out for further American reinforcements, and an additional two companies were moved into position for entry into the battle for Pork Chop Hill.

The Americans had another card to play as the continuing peace talks started to take on a life of their own. Trudeau argued that a surprise battalion-sized force taking nearby Old Baldy would relieve pressure on Pork Chop Hill and force the Chinese to divert their manpower and artillery. And the Chinese would no longer have their observation posts atop Old Baldy to call in artillery on the shorter Pork Chop Hill. This, in turn, would further block Chinese efforts to penetrate the American main line of resistance just as the peace talks were starting to show promising signs of a potential breakthrough.

Trudeau’s bold plan was disrupted by renewed Chinese counterattacks atop Pork Chop Hill and hindered by more timid officers above him in the chain of command. His superiors reluctantly gave the go ahead, but with only one rifle company to be called into play. Trudeau knew that even if the single company did manage to take Old Baldy at rather great odds it could not hold the objective against the sizable nearby enemy forces without substantial follow-on American reinforcements. He did not want to commit a single company to such an objective, knowing that even if successful it would have to pull off Pork Chop Hill in a potentially deadly fighting withdrawal. With a heavy dose of realism and some disappointment, Trudeau called off the planned assault.

Back at Pork Chop early on July 10, Company I of the 3rd Battalion, 32nd Infantry prepared to relieve the east portion of the hill, while its Company K made it onto the hill. Among those coming off the hill was Company K of the 32nd with only 12 men remaining among the 188 that had fought themselves into position only 36 hours earlier. Similarly, a platoon from Company H came back with 15 to 18 men, out of the 50 active when the platoon hit Pork Chop Hill.

The evacuation was completed by evening with Companies I and K of the 32nd well in position on Pork Chop. The Chinese sent a welcoming committee at 8:50 pm with a fiery attack against Company K on the west shoulder of the hill. The attackers were beaten back in a 40-minute fight, and Company L was called into position as possible reinforcement. Shortly after 3 am on July 11 a battalion-sized Chinese force struck Company I and overran two platoons. Company L was called to assist in successfully retaking of many of those positions.

Battalion Commander Lt. Col. Royal R. Taylor was with the men throughout the ordeal, including when an incoming enemy phosphorous round set off an ammunition storage area near the command post. He ordered his men out, helped wounded soldiers to safety, and quickly reestablished a new command post. He exposed himself repeatedly to enemy fire to support and protect his men and directed counterattacks. When the sun rose, there was again a need to evacuate the dead and wouned, and then start resupply in preparation for yet another night of onslaughts by the Chinese.

The struggle for Pork Chop Hill had raged nonstop for five days. The Chinese had committed at least a full division to the taking of Pork Chop Hill with two battalions occasionally assigned to a single assault. The Americans, commanded overall by Lt. Gen. Maxwell Taylor, met to weigh the pros and cons of continuing the fight for the outpost. After much hesitation and debate, the decision was made to pull the troopers from Pork Chop Hill in a daytime withdrawal.

The decision was based on the notion that an armistice was near and that additional bloodshed was not warranted, in part because the enemy had committed such large forces to the effort to seize the hill and suffered 4,000 casualties in the process without pause in sending more men forward toward death. The Americans on the hill were somewhat dumbfounded yet relieved by the decision to give up the tactical advantage of holding Pork Chop Hill after suffering so many losses. They had taken 243 killed and 916 injured compared to an estimated 1,500 Chinese killed and 4,000 injured in the July fighting.

In reality, the brass contended, there really was not much to save at the outpost, which would be given up anyway according to agreements reached before the armistice. The bunkers and trenches that had been painstakingly rebuilt after the April battle were now nearly in ruins thanks to the five-day, around-the-clock battering taken from exceptionally heavy artillery and mortar fire from both sides.

The Americans planned the pullout in a meticulous manner to deceive the Chinese about their intentions and thereby avoid a possible massive enemy attack on the exposed soldiers as they moved back toward the American main lines. American artillery fire was planned for protection during the delicate maneuver, armored personnel carriers were called into action, and tanks from the 73rd Tank Battalion were moved into position to help cover the withdrawal and make the operation look like an attack. Volunteers from the 13th Engineers were pressed into service to mine and booby trap Pork Chop to ensure that it would be a useless prize for those taking possession.

The carefully planned effort worked out with the Chinese led to believe that the hill was being reinforced in preparation for yet another American counterattack. Rather than reinforce the positions, the covered armored personnel carriers were used to pull the American troops off Pork Chop Hill, and the withdrawal was completed by late evening on July 11 without the loss of a single soldier.

As additional Chinese began filtering onto the hill, they triggered the booby traps left by the Americans. Once the Chinese were fully on the hill, the Americans opened fire with all the artillery they had at hand, using thousands of proximity fused rounds and heavier rounds to destroy the remaining bunkers and trenches. The rounds had a devastating effect and were supplemented with bombs dropped by U.N. aircraft. Capping it off was a large timed explosion set earlier by the engineers.

With the July 27, 1953, signing of the armistice, the war officially ended. The U.S. and U.N. troops had thwarted the naked thrust of communist aggression in Korea; in the end, South Korea remained free.

SERVED WITH THE 32ND INF. REGT., 52-53, 8 MOS. AND 20 DAYS ON THE FRONT LINES. APRIL OF 53 I WAS ON PORK CHOP HILL AND LATER ORDERED OFF THE OUTPOST…I DO NOT REMEMBER ANY OF THE TIME I SERVED ON THE HILL, ONLY THAT I WAS TOLD TWO OF OUR MEN SHOT THEMSELVES TO GET OFF THE OUTPOST. I KNEW THE TWO MEN BUT I WAS NOT THERE, THAT I REMEMBER, WHEN THEY SHOT THEMSELVES. COMING OFF THE OUTPOST I HAD A VERY FUZZY FEELING IN MY HEAD, NOT REMEMBERING ANYTHING ABOUT THE FIGHTING. WE WERE ALL PULLED OFF PORK CHOP AND I ASKED SOMEONE WHY WE WERE BEING PULLED AND WAS TOLD THAT WE WERE PULLED AT THE DIRECTION OF A PSYCHIATRIST. AT THE TIME, LIKE I SAID A FUZZY FEELING IN MY HEAD, WITH NO FEELING OF FEAR, JUST NOT REMEMBERING ANYTHING AT ALL ABOUT ANY FIRE FIGHTS OR OTHER POSSIBLE CONTACTS WITH THE CHINKS. NEVER COULD FIGURE OUT WHAT HAPPENED ON PORK CHOP HILL. ANY HELP I WOULD APPRECIATE AN ANSWER. THANK YOU AND GOD BLESS

John,

My uncle, Bill DeBiase was with the 32nd regiment on Old Baldy and Pork Chop. I’m thinking he was in B Company since he mentions Lt. Vahlsing who was killed on Pork Chop. I am writing a book about my uncle and his time in Korea and would like some additional input from veterans such as yourself. Could you email me your phone number so I can follow up. Thanks.

Joe Kolb