By William E. Welsh

England’s long downward slide to defeat in the Hundred Years’ War began with the failed siege of Orleans in 1428. For the next 25 years, the English clung to their dwindling possessions in France like a parent to an only child, while French King Charles VII of the Valois dynasty slowly chipped away at them, one piece at a time. By 1440, the French had driven the English completely from the valley of the Loire, and the English retained only Normandy in the north and Gascony in the south. The Truce of Tours in 1444 gave the French a much-needed respite, during which time Charles completed some necessary military reforms and prepared for the final grinding campaigns in a conflict that had begun more than a century earlier—well before anyone’s living memory.

Soon, the war started up again. Under the weak kingship of Henry VI, England seemed powerless to stop the French offensive of 1449 to recapture Normandy. A three-pronged thrust led by John, Count of Dunois, better known as the “Bastard of Orleans,” vanquished the English from the duchy within a year’s time. Emboldened by his success in retaking Normandy so quickly, Charles immediately began plotting the conquest of Gascony. It promised to be more difficult than the Normandy campaign. The English had occupied Normandy for only three decades, but they had controlled the province of Gascony since the middle of the 12th century, when Eleanor of Aquitaine wed Henry, Count of Anjou, who subsequently became England’s King Henry II. Despite the capture by the Capetian dynasty of much of the Duchy of Aquitaine in the early 13th century, Gascony remained solidly under the rule of the English Plantagenets.

The French Invasion of Gascony

Using the same strategy that worked so well in Normandy, Charles mobilized three armies in 1450 to invade Gascony and bring about the final end of English rule in France. During the years immediately following the Truce of Tours, the French king had undertaken a major reform of his military forces. First and foremost, Charles forbade anyone other than himself to recruit French forces, a move designed to eradicate the bands of uncontrolled brigands that roamed the countryside during the frequent lulls in the conflict. He then formed a professional army that included infantry, cavalry, and artillery. The existing cavalry was combined into 20 compagnies d’ordonnance, each of which contained 100 “lances.” Each lance comprised one mounted man-at-arms and five more lightly armed auxiliaries. As for infantry, Charles required each parish to maintain and equip one archer, and he exempted all volunteers from any form of taxation. The professional horse and foot soldiers were augmented by the best artillerymen of the era, organized into a permanent force under the expert leadership of the king’s masters of artillery, Jean and Gaspard Bureau.

Charles would employ essentially the same strategy in loosening the English grip on Gascony that he had used to retake Normandy. Rather than invading with one army, Charles ordered his three small armies to advance on the region from different directions. In this way, he hoped to bait the English into fighting in the open rather than allowing the conflict to drag out into a series of costly sieges. Preparations were made throughout the first half of 1450, and the armies were ready to take the field by the end of the summer.

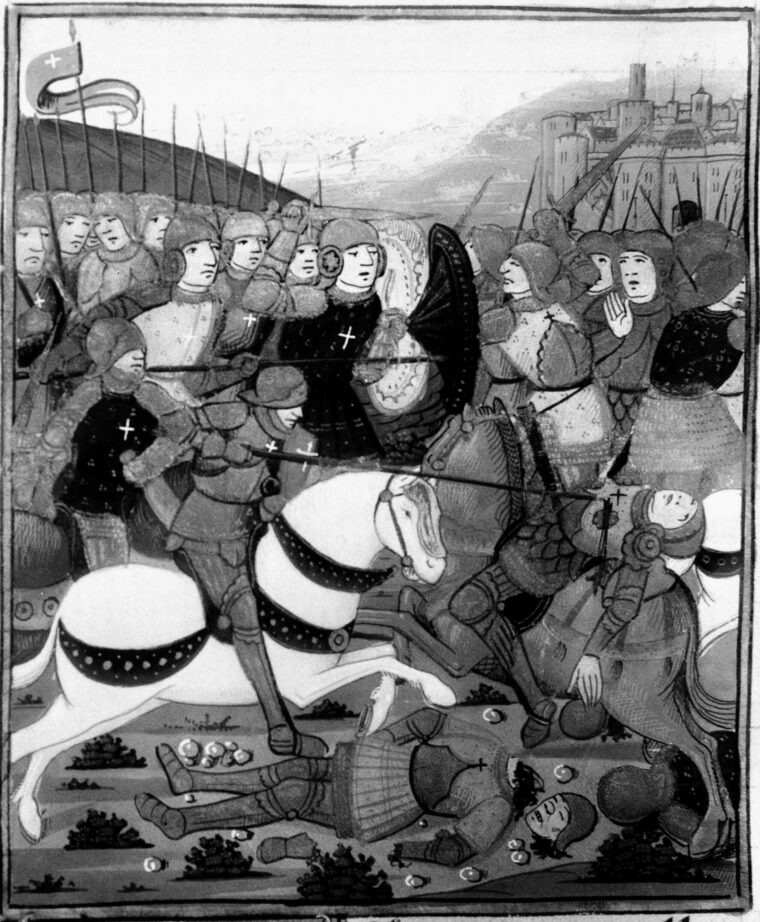

Following the king’s plan, the Count of Foix began the invasion with an advance up the Adour River toward Bayonne, while the Count of Penthievre led a Breton force along the Dordogne River valley. The Bretons reached Bergerac in Perigord in October and continued west to Bordeaux on the Gironde River. As the English seat of government in Gascony, Bordeaux was the most important objective of the French forces. The French laid siege to the city before the onset of winter. In the spring of 1451, Dunois marched south with a third army and joined the forces encamped around Bordeaux. A combined fleet consisting of French, Breton, and Spanish ships closed the mouth of Gironde, making it impossible for the English to resupply their beleaguered port.

Upon his arrival, Dunois demanded that the English garrison surrender at once. The garrison’s commander at the time, the Captal de Buch, whose ancestor John de Grailly had fought with the “Black Prince” Edward at Poitiers in 1356, told Dunois that he would surrender the city if no aid arrived from England by June 14. As the English were unprepared at the time to send a relief force, the garrison was left with no choice but to let the French enter the city, which they did on June 30. Less than two months later, Bayonne fell to Foix. It was the first time the French had controlled Gascony in almost three centuries.

Lord John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury

By retaking Gascony, it appeared that the French had finally managed to end the Hundred Years’ War. But it was not yet so. The pro-English population resisted Valois rule, using both overt and covert methods. On their region’s behalf, a number of Gascon exiles living in England pleaded with Henry VI to send an invasion force to liberate their homeland. Henry acquiesced and turned to veteran commander John Talbot, the Earl of Shrewsbury, to raise a relief force and transport it to southern France.

Lord Talbot, at age 65, was a veteran with more than three decades of experience fighting the French on the Continent. In his youth, Talbot had been well schooled in the art of warfare by his family elders, seeing action first at the age of 16 at the bitter Battle of Shrewsbury and helping suppress the Welsh rebellion begun by Owen Glendower in the first decade of the 15th century. In 1414, King Henry V appointed Talbot to serve as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. No stranger to partisan warfare by that time, Talbot became known for a method of fighting that involved rapid marches to surprise his enemies and keep them off balance. It was an age that required a strong measure of ruthlessness if a commander were to succeed in getting the better of his enemies, and Talbot took well to the task. One Irish nationalist said of Talbot that “from the time of Herod there came not anyone so wicked.”

Talbot joined the English war effort in France in 1419 and participated in a series of military actions in the Ile de France, the region surrounding Paris. He fought valiantly under John, Duke of Bedford, in the Battle of Verneuil in 1424. Throughout his service in France, Talbot’s role was that of a captain serving under the king’s lieutenant in France, the person charged with waging war on Henry VI’s behalf. Talbot excelled in raids that required stealth, but he was less successful in open battle. Following the English withdrawal from Orleans in May 1429, Talbot’s army was overrun by the French at the Battle of Patay. Talbot was captured during the rout and subsequently spent four years in captivity. He was captured again during the Normandy campaign of 1449-1450, when the French laid siege to Rouen in the first year of the campaign. Eventually Talbot and seven other English hostages were released in July 1450.

Neither his defeat at Patay nor his time as a prisoner of the French did anything to diminish Talbot’s fierce reputation. Indeed, his reputation as an enemy commander worth fearing remained intact even after the English lost their hold on Normandy. It was said that French mothers frightened their children into obedience by telling them that if they didn’t behave, “Le Tal-bote” would get them.

Taking Back Gascony

Talbot set sail in September 1452 for Gascony with an expeditionary force of about 3,000 men, many of whom he had recruited from his own estates at Whitchurch, Sheffield, and Painswick. Although looking somewhat askance at the “hedge-born swain” he was bringing with him from England, Talbot could count on such grizzled veterans as John Montfort, John Sterky, Thomas Dowe, John Hensacre, John Le Prince, Robert Stafford, and Richard Bannes to lead the troops into combat when the time came. On October 17, Talbot’s force waded ashore in the Medoc section of Gascony, northwest of Bordeaux. Talbot’s landing caught the French by surprise, as they expected the English to try first to recapture Normandy. The Gascons, who welcomed Talbot’s arrival, opened the gates of Bordeaux to the English on the night of October 22. Talbot spent the following weeks working with the Gascons to expel French garrisons scattered in fortified towns and castles throughout the region. By pushing into the Dordogne valley and retaking Libourne and Castillon, he set up a buffer zone against an expected French counterattack on Bordeaux.

By Christmas 1452, most of Gascony was once again under English rule. Some of the Gascons may have regretted the ease with which they allowed the English to resume control, as Talbot established a tax on the local population to pay for the cost of fielding his army. During the winter months, Talbot’s fourth son, Viscount Lisle, assembled about 2,300 reinforcements and sailed to Gascony to join the elder Talbot.

Determined to drive the English from Gascony, Charles VII devoted the winter of 1452-1453 to building up a force that would be large enough to defeat Talbot—“the English Achilles”—in open combat. The French king assigned overall command for the 1453 campaign to the Lord of Clermont. Jean Bureau would command the artillery within Clermont’s army, while the Count of Penthievre would lead the mounted lancers, or gens d’ordonnance. Once again the French split into three groups as they approached Gascony. This time, however, all three armies would slowly converge on Talbot’s position in Bordeaux, capturing strongholds occupied by English or Gascon forces as they advanced. Even as the French closed in on his army, Talbot launched a swift raid on Fronsac on the Isle River, a tributary to the Dordogne, but just as quickly fell back to the safety of Bordeaux. By early summer, Clermont had slipped past Talbot and was encamped in the Medoc section of Gascony.

Talbot’s Abandoned Strategy

On June 21, Talbot sent a verbal challenge to Clermont and the other French commanders to march out and meet him in open battle at Martignas. The French, however, were not ready to give battle, and for once they resisted the time-tested English tactic of baiting them into a headlong attack. Talbot determined that he was substantially outnumbered and returned to Bordeaux. The likelihood of a major clash between the two sides was inevitable, and the English veteran saw that his only hope of victory, in the face of an enemy twice his size, was to fall on the smallest French column first and defeat it quickly before it could be reinforced. Once again, it seemed that the French would oblige him. In early July, Bureau’s army marched down the Dordogne River and prepared to lay siege to Castillon, a small wine-trading town on the north bank of the river, 30 miles east of Bordeaux.

While Clermont remained in the Medoc, Bureau’s army advanced along the Dordogne like a dagger pointed straight at Bordeaux. His forces included the main French artillery train. While as many as a half dozen captains saw to the archers and the gens d’ordonnance, Bureau had complete authority over the siege operations necessary to reduce enemy strongholds. The powerful force reached Castillon on July 13 and immediately went into camp east of the city. A detachment of archers was dispatched to occupy the St. Laurent Priory north of the city, a position from which it could alert the main body to the arrival of an English relief force.

Bureau’s decision to establish his main force in an artillery park east of the city was a cautious move. By doing so, he hoped to avoid being trapped between a relief force led by Talbot, approaching from the west, and the town’s pro-English inhabitants. In keeping with the tactics of the day, Bureau’s artillery park would allow the French to develop a siege slowly and methodically without exposing their own forces to enemy attack in the process. Once the artillery park was established, the French could go about building trenches and moving up guns, knowing that they could retreat to the safety of the artillery park if the enemy attacked in force.

From the safety of Bordeaux, Talbot waited for an opportunity to strike and defeat the smaller French armies maneuvering toward the city. Once they were defeated, he planned to turn his attention to Clermont’s main army. As soon as the French arrived at Castillon, the townspeople sent a request to Talbot imploring him to come to their aid and drive off the besieging army before the town could be surrounded. The burgesses in Bordeaux joined a growing chorus of Gascon voices urging Talbot to drive the French from Castillon. Talbot explained his strategy at length to the burgesses of both towns, but they did not accept his rationale. Instead, the authorities in Bordeaux openly disdained Talbot for his inaction. Talbot took the rebuff badly, and after a few days he agreed to march to the aid of Castillon, even though it was against his better judgment.

Bureau’s Artillery Park

Seven hundred French pioneers toiled around the clock for four days to construct Bureau’s fortified artillery park east of Castillon. The park was roughly 700 yards long and 200 yards wide. The forces were tightly packed within its 30-acre interior. The site Bureau chose paralleled the Dordogne, which flowed less than a mile to the south and was anchored on the smaller Lidoire, a tributary of the Dordogne. On the north side, the Lidoire’s relatively steep banks served as a natural moat and wall against any attack from that direction. The pioneers dug a deep ditch for the other three sides of the rectangular artillery park. Behind the ditch they erected an undulating wall with a number of strongpoints to provide interlocking fields of fire. The pioneers also built a strong palisade, using excavated dirt and felled trees, behind the ditch to protect the men and guns. They put the main gate in the south wall opposite the Dordogne. By sundown on July 16, the fortification was complete and the French position secure.

The French had 6,000 to 7,000 troops inside the artillery park. Another 1,000 Breton gens d’ordonnance were stationed on forested ground about 11/2 miles to the north, on the opposite side of the Lidoire. All told, the French had nearly 300 guns of all sizes within the park, massed wheel to wheel. The ordnance included culverins, serpentines, arbalests, and projectile launchers (crude, hand-held forerunners of the musket). The most effective were the culverins, lightweight cannons capable of firing .30-caliber balls through their five-inch bronze barrels. Smaller hand and swivel guns were mounted along the wall, while the larger guns were concentrated in strongpoints. When the English finally arrived, they would find the earthen walls literally bristling with guns.

Bureau had designed the fort in such a way that an attacking force would find it hard to develop a successful attack. For one thing, an attacker would find it almost impossible to launch a frontal attack across the natural barrier of the Lidoire. Another poor proposition was an attack against the west wall’s extremely narrow front of less than 200 yards. And any attack from the south would mean that the attackers would have the Dordogne at their back. All three approaches carried high risks and seemed to offer little chance of success.

At dawn on July 16 Talbot marched his entire army through the gates of Bordeaux and east toward Castillon. Behind him was a combined force of 5,300 English and 3,000 Gascons. Talbot rode with a hand-picked vanguard of 500 men-at-arms and 800 mounted archers. Behind them trudged the dismounted troops and a smattering of artillery, panting to keep up. In the humid summer weather the English advanced along the north bank of the Dordogne, arriving at Libourne at sundown. After a brief rest, Talbot’s vanguard continued east on a forested path to Castillon.

After a 12-mile ride, the English reached Castillon just as the sun rose over the horizon. Under cover of darkness, the English had been fortunate not to encounter a single enemy picket on their march. Stationed within the buildings and on the grounds of the St. Laurent Priory, the 1,000 French archers were oblivious to the enemy’s approach. The only pickets they had posted were on the main road south toward Castillon.

On Talbot’s order, the English swooped down on the sleeping priory, catching many of the French archers still in their bedrolls. In a furious melee that ended almost as quickly as it began, the English overwhelmed the enemy detachment. The enemy archers who were not slaughtered on the spot fled to the artillery park a mile away. Talbot’s raid on the priory was a complete success. Bureau and the French captains in the artillery park made no effort to retake the priory. It had served its purpose as a forward observation post, even if it had fallen to the English in the process. Spirits soared among the English as they cleared the priory and secured the grounds for the rest of the troops, who were just then departing from Libourne at the time of the attack.

Talbot’s Gambit

After marching more than 30 miles from Bordeaux to Castillon, Talbot decided to rest the vanguard and await the arrival of the main body of troops. He allowed his men to help themselves to the dead Frenchmen’s food, and even ordered up a celebratory cask of wine for the men. Meanwhile, he sent a scouting party under Sir Thomas Everingham to reconnoiter the French position west of Castillon. The famished Englishmen were just beginning to consume their meal when Everingham returned to report that the main French force at Castillon was well protected behind a strong rampart.

A small number of burgesses and messengers made their way from Castillon to the priory as soon as it became apparent that the English had driven off the French archers. One messenger carried word to Talbot that a number of the townspeople had observed large clouds of dust to the east, from which they inferred that the French were withdrawing. In fact, what they were seeing was the attendants inside the artillery park moving their horses to another location to make room for the archers who had fled the priory.

Talbot heard the report just as his personal chaplain was preparing to say prayers before the meal. He had to decide whether to continue to press the attack before his men had finished their meal, or wait for the rest of his infantry to arrive. Everingham urged him to wait for reinforcements, but Talbot already had made up his mind. He ordered his subordinates to reform the vanguard for a fresh attack. He was taking a considerable gamble. If the French were indeed withdrawing, the English would probably be able to inflict considerable damage to their army. But if the information brought by the messenger was incorrect, Talbot would face the entire French army with only a fraction of his own command. He told his chaplain to delay saying mass—he would worship after he had beaten the French once and for all.

Talbot formed the English vanguard and led it east. The vanguard splashed through a ford of the Lidoire and rode onto the open plain between the artillery park and the Dordogne. The English men-at-arms and archers dismounted for a foot assault. As for Talbot, he remained mounted to control the deployment of his men. As one of the conditions of his release from French captivity, Talbot had agreed never to wear armor or take up arms again against the king of France. In keeping with this pledge, Talbot refrained from wearing any armor or carrying a sword into battle at Castillon. Astride a white horse, Talbot was one of the most conspicuous soldiers on either side of the battlefield. His shoulder-length white hair streamed from under a purple velvet cap, and he wore a crimson cloak to signify his rank and privilege. He was observing the letter, if not necessarily the intent, of his parole.

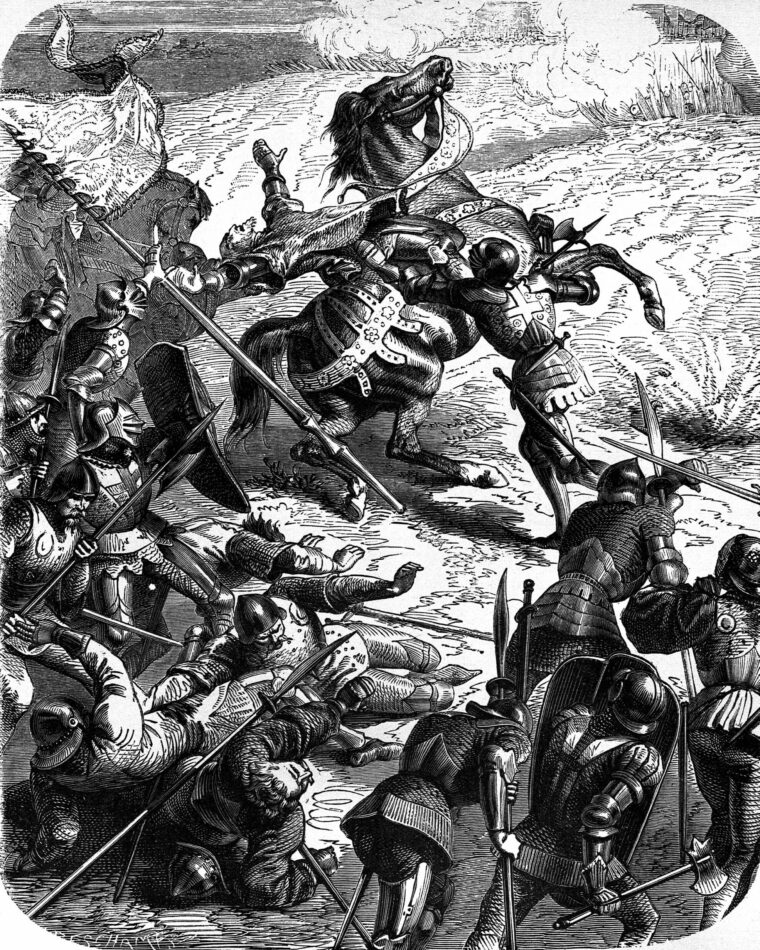

Talbot was shocked when he saw that the French had not fled, but were calmly awaiting his approach. Despite the fact that the enemy camp was bristling with cannons and men-at-arms, Talbot believed the sheer fury of his assault would either breach the fort or convince the French to retire. Against the renewed advice of Everingham to wait for the rest of the infantry to arrive, Talbot ordered his captains to organize the men into two equal-sized groups. Once the attack started, the men-at-arms would advance while the archers fired over their heads from a distance. Obediently, the vanguard advanced in two groups toward the palisade. The men stepped off briskly, shouting, “For Talbot and St. George!” They leaped into the wide ditch and scrambled up the steep dirt walls. One of the English formations slammed into the west side of the artillery park nearest Castillon, while the other charged the east side.

As the English advanced, the French unleashed a withering blast of cannonfire from their large and small guns, raking the enemy ranks and producing heavy casualties. Despite the accuracy of the nearly point-blank fire, the English closed ranks and pressed on. Those who managed to live through the first blistering fire from the culverins and swivel dove for temporary protection into the dry moat at the base of the palisade. The English rose again with a shout and scaled the rampart. Hand-to-hand fighting with swords and battle-axes broke out all along the wall. The French met the attackers with swords and primitive handguns.

One of the first attackers to reach the rampart was Everingham, who was serving as Talbot’s standard-bearer. Amid the swirling melee, he and a small knot of soldiers ascended the palisade, and Everingham plunged his banner into a section of the rampart nearest the fort’s entrance. He was killed almost immediately by a gunshot. The reinforcements he had urged Talbot to wait for before attacking arrived on the field in dribs and drabs and dashed pell-mell into the fray. French artillery raked the field, bowling over as many as six Englishmen at a time.

The French had deployed their guns along the irregular wall in a way that created interlocking fields of fire to break up attacking forces. They turned some of their bombards away from the walls of Castillon and toward the attackers. The larger pieces tore great swaths in the English ranks. “The artillery caused grievous harm to the English,” wrote a French participant, “for each shot knocked down five or six men, killing them.” The fallen lay wounded on the field, pleading for help as the dead piled up around them on the killing ground between the two armies.

By flinging his men against the French without any artillery of his own, Talbot had recklessly squandered the elite of his army. As more reinforcements arrived, Talbot waved them into battle. By the end of the fighting, Talbot probably committed 4,000 men—almost half of his entire army—to the ill-planned assault. His artillery, which was at the back of the army, did not arrive in time for the battle. The fire from the French guns continued to take a devastating toll on the English ranks as the battle wore on. The initial assault in which Everingham participated may have been the closest the English got to fighting their way into Bureau’s artillery park.

Crushing the English Flank

The battle had been going on for about 90 minutes when the French gens d’ordonnance suddenly appeared on the English right flank. Before the battle, the mounted Breton men-at-arms had camped atop high ground in the forest directly north of the artillery park. Unseen, the French cavalry forded the Lidoire east of the artillery park and reformed for a charge on the exposed English right flank. The French heavy cavalry easily rolled up the exhausted enemy flank in front of them. Talbot dispatched a body of soldiers to guard his unanchored flank, but they were forced to give ground to the cavalry. As the Bretons rolled up the English flank, men and banners alike were trampled under the horses’ hooves. The English broke and fled toward the Dordogne.

As soon as French inside the artillery park saw the flank attack was a success, they leaped over the parapet and advanced on the English. Talbot’s attack fell apart, and the English found themselves on the defensive. The French cavalry, assisted by the French archers now fighting hand-to-hand with the English, drove the English back toward the Dordogne. The French archers dispatched any wounded Englishmen unworthy of ransom with a knife to the throat.

Seeing at a glance that his army had no chance for success once the mounted Bretons arrived, Talbot began looking for a way out of his predicament. The French were driving the English south toward the river, which would make it difficult to withdraw west across the Lidoire, the route by which they had arrived on the battlefield. He and his captains searched frantically for a shallow section of the Dordogne that would allow them a chance to get away. Meanwhile, Lisle tried desperately to organize a rear guard to protect the crossing.

While the English were reorganizing, the French gunners continued shelling their ranks. One of the shells struck Talbot’s horse. Horse and rider toppled over, and Talbot found himself pinned beneath his mount. By that time, French archers and men-at-arms had infiltrated the English ranks. Talbot’s aides scrambled to reach their commander and take him to safety. An alert French archer named Michel Perunin also saw the English leader go down and rushed to the spot where the dreaded “Tal-bote” lay. Perunin reached Talbot first, dismounted, and casually dashed out the old man’s brains with a battle-axe. “Such was the end of this famous and renowned English leader, who for so long had been one of the most formidable thorns in the side of the French, who regarded him with terror and dismay,” wrote the contemporary French chronicler, Matthew d’Escoucy.

Cut off from their route of advance and with the river behind them, the English found it almost impossible to extricate themselves from the fight. The gens d’ordonnance surrounded any knot of resistance on the banks of the Dordogne. Those Englishmen who were still alive continued searching for a way across the Dordogne. A significant number drowned while attempting to swim or wade across the river. In the thick of the action, Talbot’s son, Lord Lisle, also became a target for the French lancers. He was cut down just as some of the English troops found a crossing known as the Pas de Rozan a short distance upstream. A small number of the English managed to cross to safety, but Talbot’s army was no longer in any condition to fight. The remainder of his defeated army, including those who had not joined the main battle before it was over, streamed west and did not stop until they reached the safety of Bordeaux. Part of the French army at Castillon pursued the English as far as Saint-Emilion before stopping to regroup.

One member of the English army stayed behind. The following day, Talbot’s herald received permission from the French to search the field for Talbot’s body. Although the body was badly disfigured, the herald was able to identify it by a missing tooth. That same day, the town of Castillon surrendered to the French and was spared the sword. Talbot’s body was returned to his family in Shropshire for burial. On the spot where he died, French noblemen erected a small stone chapel in his memory. It survived until the French Revolution 300 years later, when nationalist zealots tore it down. A new monument erected at the crossroads north of the battlefield gives a brief but pungent account of the battle: “On 17 July 1453,” it reads, “Gascony was delivered from the yoke of England.” In his own dramatic account of the battle, Henry VI, Part One, William Shakespeare adjudged it “a dismal fight/Betwixt the stout Lord Talbot and the French.”

During the following week, the French arrived in force on the outskirts of Bordeaux and laid siege to the city, where a garrison of 3,000 English and Gascon troops had taken shelter after the disaster at Castillon. They held out for three more months before agreeing to an unconditional surrender on October 19. Having lost all patience with the Gascons, Charles VII fined the city 100,000 gold crowns for resisting his authority. He also banished the nobles who supported the English. For his service to the crown, Charles appointed Jean Bureau as Bordeaux’s mayor for life. The Hundred Years’ War, once and for all, was over.

English territory in France, which had been extensive since 1066 (see Hastings, Battle of) now remained confined to the Channel port of Calais (lost in 1558). France, at last free of the English invaders, resumed its place as the dominant state of western Europe.