By Michael D. Hull

While America and Europe struggled through economic depression and nervously watched the spread of fascism in the second half of the 1930s, the situation was far more ominous in the Far East.

Expansionist Japan had sown the seeds of war in China early in the decade, and hostilities broke out in July 1937. By that autumn, Japanese troops were advancing. Drunken and undisciplined soldiers pillaged and burned towns and villages; civilians were captured and shot, and females of all ages were raped, murdered, and mutilated.

There were no limits to Japanese brutality; piles of Chinese bodies were even used for grenade-throwing practice. A Japanese general apologized to a Westerner by saying, “You must realize that most of these young soldiers are just wild beasts from the mountains.”

Japanese troops marched into the city of Soochow in eastern China on November 19, and the roads to the great cities of Nanking and Shanghai were open to them. When Japanese units approached Nanking on November 21, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s office notified the American Embassy that it should prepare to evacuate. Ambassador Nelson T. Johnson and most of his personnel left the next day aboard the gunboat USS Luzon. Chiang, his wife, and remaining members of the Chinese government fled from the threatened city on December 8.

Japanese diplomat Yosuke Matsuoka explained that his country was fighting to achieve two goals in China: to prevent Asia from falling completely under white domination and to stem the spread of communism.

Japanese troops soon triumphantly entered Nanking and began a month of unprecedented atrocities. They roamed the city looting, burning, raping, and murdering. Men, women, and children were “hunted like rabbits.” Wounded and bound prisoners were beheaded, and an estimated 20,000 men and boys were used for live bayonet practice. Even the friendly Germans in the city issued an official report branding the Japanese Army as “bestial machinery.”

The invaders were supported by a new policy ordering the sinking of “all craft on the Yangzi River,” regardless of nationality. The aim was to leave China’s principal waterway clear for Japanese operations. The order came from Colonel Kingoro Hashimoto, founder of the Cherry Society, the Army’s “Bad Boy,” and commander of artillery batteries along the Yangtze River. He told his men to “fire on anything that moves on the river.”

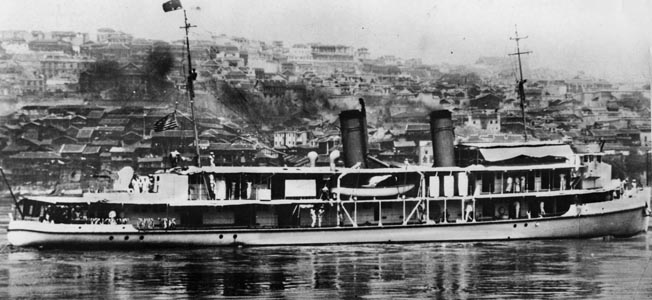

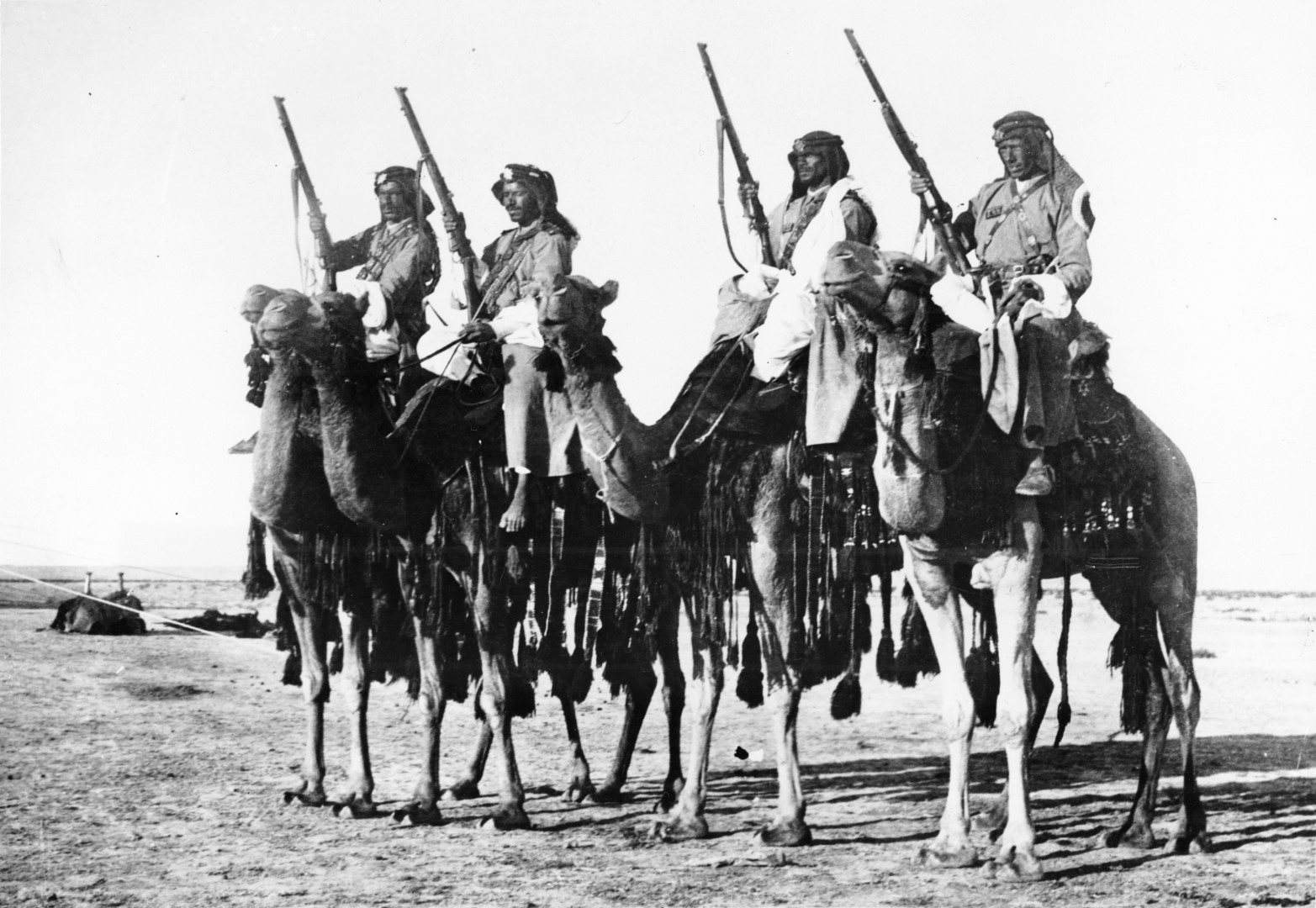

To protect Western citizens, legations, and business interests, the waterway and its tributaries had been continually patrolled since the 19th century by British and American gunboats. The U.S. Asiatic Fleet established supply depots in Tsingtao, Hankow, and Canton and organized gunboats, which had been operating on the river since 1903, into the famed Yangtze River Patrol (Yangpat) in December 1919. Its first commander was Captain T.A. Kearney.

The U.S. Navy’s presence in China was lengthy. In 1832, President Andrew Jackson sent the 44-gun frigate USS Potomac to defend merchant ships against piracy in East Asia. She was commanded by Captain Lawrence Kearny, a veteran of piracy patrols in the Caribbean and Mediterranean. Named commander of the Navy’s East India Squadron, Kearny sailed from Boston to Macao and Canton aboard the 36-gun frigate USS Constellation in March 1842, just as the British-Chinese Opium War was ending. A skilled diplomat as well as a gallant sailor, Kearny formed good relations with Chinese officials.

U.S. Navy vessels were thereafter regularly assigned to East Asia, and in 1854 the side-wheel gunboat USS Ashuelot became the first American ship to patrol the Yangtze River. The Sino-American Treaty of 1858 granted U.S. warships the right to navigate all Chinese rivers and visit all ports. U.S. naval activity increased significantly after victory in the Spanish-American War in 1898, which led to the annexation of the Philippine Islands, and American naval units served in the Boxer Rebellion of 1899 when Chinese insurgents besieged the foreign legations in Peiping.

The Yangtze Patrol comprised 13 vessels, including nine gunboats, and 129 officers and 1,671 enlisted men. In addition, 814 men of the 15th Infantry Regiment were stationed in Tientsin, 528 U.S. Marines in Peking, and another 2,555 Leathernecks in Shanghai.

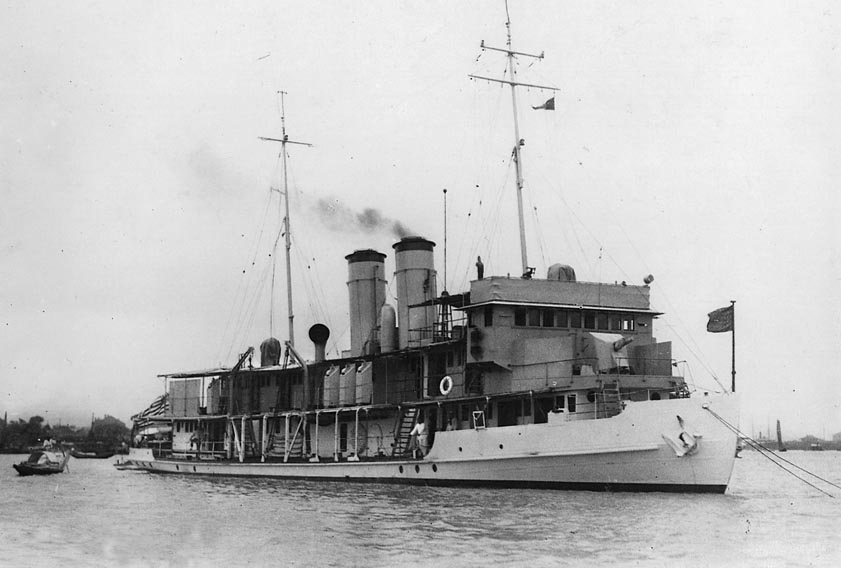

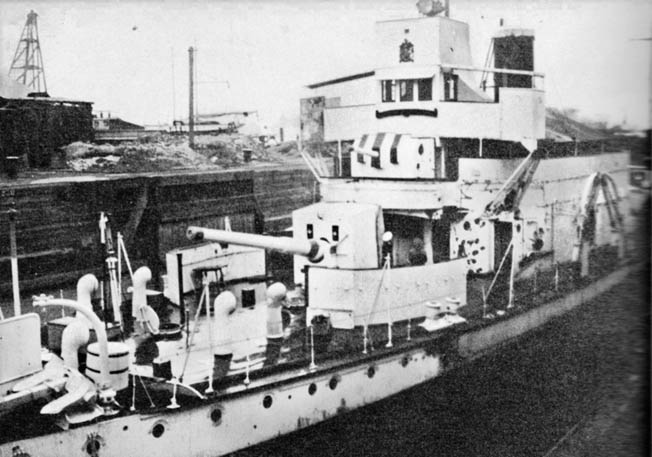

As revolutionary upheavals swept the country after World War I, the U.S. Navy beefed up its presence on the Yangtze in 1927-1928 by deploying six gunboats built in China and designed especially for river duty. They were the Guam, Luzon, Mindanao, Oahu, Tutuila, and the aging Panay.

The British and American sailors tensely plying the great waterway faced heightened danger as Japanese aggression mounted through the 1930s. The perceptive U.S. ambassador to Tokyo, Joseph C. Grew, reported that American-run churches, hospitals, universities, and schools across China had been bombed despite flag markings on their roofs, and missionaries and their families killed. Stressing that the attacks were planned, he loudly protested the pillaging of American property.

As Japan’s undeclared war intensified, focusing especially on Shanghai with its international business settlement, President Franklin D. Roosevelt warned Americans in China that they should leave for their own safety. If anything happened to them or their property, he said, “The United States has no intention of going to war either with China or Japan, but instead would demand redress or indemnities through orthodox, friendly, diplomatic channels.”

The man on the spot was Iowa-born, 61-year-old Admiral Harry E. Yarnell, new commander-in-chief of the U.S. Navy’s Asiatic Fleet. An Annapolis graduate and veteran of the Spanish-American War and the Boxer Rebellion who had successfully “attacked” Pearl Harbor during war games in 1932, Yarnell commanded only two cruisers, 13 destroyers, six submarines, and 10 gunboats. Yet, on September 27, 1937, he sent an order to his fleet contradicting FDR’s policy.

“Most American citizens now in China are engaged in businesses or professions which are their only means of livelihood,” said the admiral. “These persons are unwilling to leave until their businesses have been destroyed or they are forced to leave due to actual physical danger. Until such time comes, our naval forces cannot be withdrawn without failure in our duty and without bringing great discredit on the United States Navy.” Yarnell reported his fleet order to Washington and, surprisingly, it was not countermanded by Roosevelt.

Public opinion supported the admiral’s initiative, and FDR fell in line. In an October 5 speech, the president declared, “When an epidemic of physical disease starts to spread, the community approves and joins in a quarantine of the patients in order to protect the health of the community.” His listeners understood what he meant.

The uneasy quiet along the River Yangtze was shattered at 9 am on Sunday, December 12, 1937, when Colonel Hashimoto’s gun crews opened fire on the Royal Navy gunboat HMS Ladybird. Four shells struck the vessel, killing a sailor and wounding several others. A British merchant ship and four other gunboats were also fired on. Twelve miles above Nanking, a Japanese air attack missed the gunboats HMS Cricket and HMS Scarab, which were escorting a convoy of merchant ships carrying civilian refugees, including some Americans.

Alarmed by the attacks, Ambassador Johnson hastily composed a telegram that morning to the secretary of state in Washington, the embassy office in Peiping, and the American consul in Shanghai. Dispatched by the gunboat Luzon at 10:15 am, the telegram urged the State Department to press Tokyo to call a halt to attacks on foreigners in China. Prophetically, Johnson messaged, “Unless Japanese can be made to realize that these ships are friendly and are only refuge available to Americans and other foreigners, a terrible disaster is likely to happen.”

That same morning Admiral Yarnell sent a message to the USS Panay ordering her to get underway at the discretion of her skipper, Lt. Cmdr. James J. Hughes. Japanese shells had been landing regularly and close to the gunboat.

At 8 am the previous day, the Panay had embarked Ambassador Johnson, American officials, and some civilians and started upriver on a five-mile journey. The gunboat escorted three Standard Oil Co. barges, the Mei Ping, Mei Hsia, and Mei An and was followed by a few British craft. American flags were hoisted on the barges’ masts and painted on their awnings and topsides. For two miles, moving slowly against the current, the vessels were fired on by Japanese shore batteries. But the shooting was wild, and the little flotilla was able to pull out of range without suffering hits.

The Panay and the barges anchored near Hoshien, about 15 miles above Nanking, at 11 am on December 12. The berth was in a wide space that seemed secure, 27 miles away from the fighting around Nanking.

A veteran of service in the Philippines before World War I, the 450-ton Panay (PR-5) had been commanded in 1907 by a 22-year-old ensign named Chester W. Nimitz, later to gain fame as the commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet in World War II. The shallow-draft, two-funnel gunboat was capable of 15 knots, and her crew comprised five officers and 54 men. She mounted a main battery of two high-angle, three-inch guns and eight .30-caliber Lewis machine guns of World War I vintage. The vessel was painted white and buff, and two large U.S. flags, 18 feet by 14 feet, were painted horizontally on her upper deck canvas awnings. The flags were clearly visible from the air at any angle.

The mixed crowd aboard the gunboat that morning included several newsreel cameramen who had just completed a short documentary film about the Panay.

The day was sunny, clear, and still. The gunboat crewmen ate their noon meal, secured, and got ready for a peaceful Sunday afternoon. Eight bluejackets were permitted to take a sampan over to the Mei Ping for some cold beers, and others took naps. The Panay’s guns were covered and unmanned.

Meanwhile, an attack force of 24 Japanese naval bombers, fighters, and dive bombers had been formed up after the Army mistakenly reported that 10 ships laden with refugees were fleeing up the Yangtze from Nanking. It was a golden opportunity for eager young Navy pilots to attack ships instead of ground targets. The enemy fliers took off with such haste that no strike plan was set up. They roared toward the river.

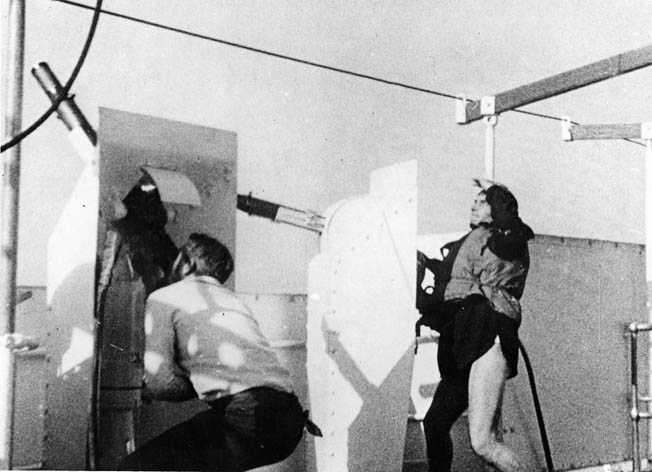

Suddenly, at 1:37 pm the Panay lookout reported two aircraft in sight at about 4,000 feet. Commander Hughes peered from the pilothouse door to see planes rapidly losing altitude and heading his way. Three Aichi D1A2 “Susie” dive bombers flew over the gunboat and released 18 bombs. Seconds later, an explosion threw Hughes across the pilothouse, breaking his thigh.

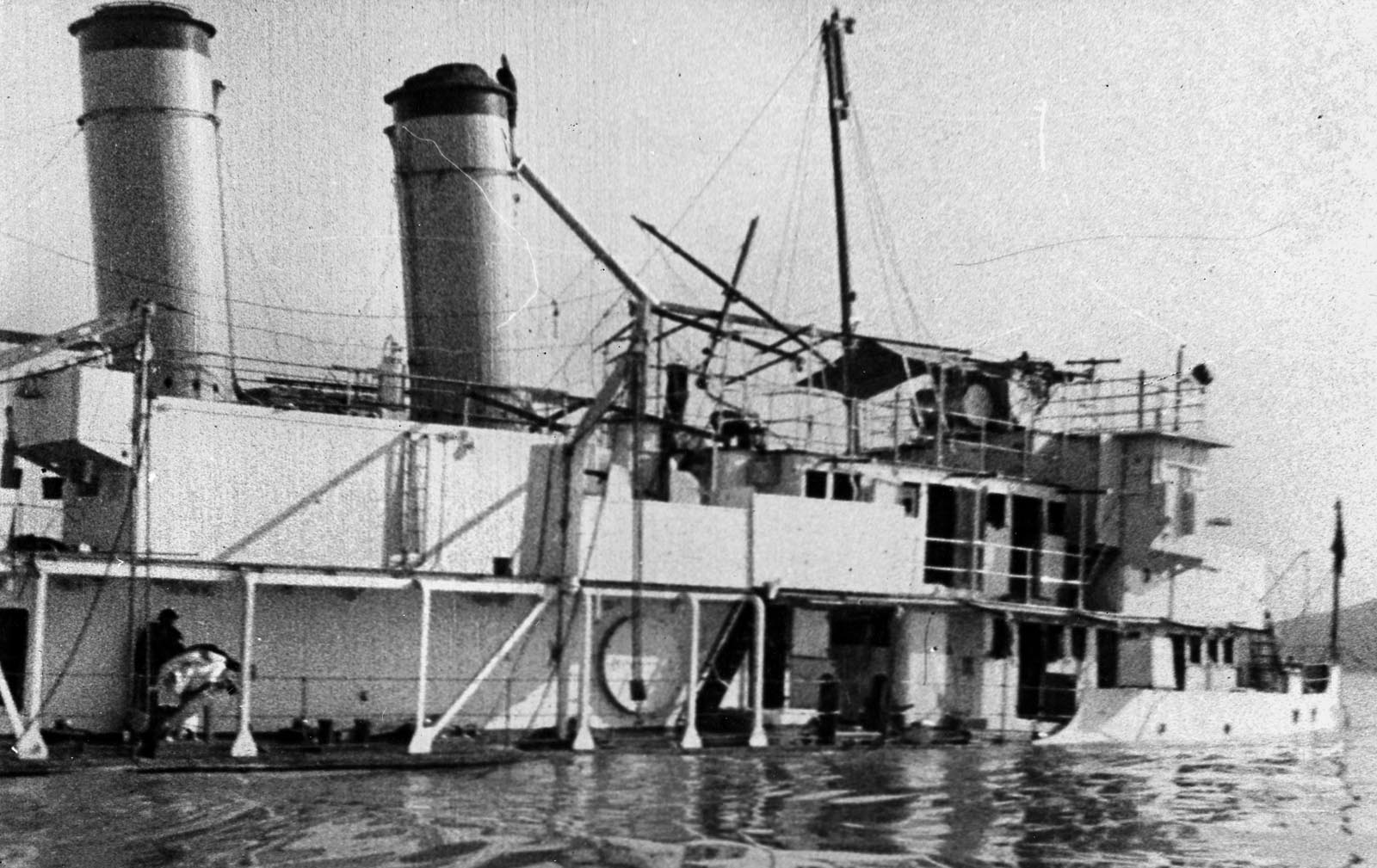

The bombs felled the gunboat’s foremast, knocked out the forward 3-inch gun, and wrecked the pilothouse, sick bay, and fire and radio rooms. When he regained consciousness, Hughes found the bridge a shambles. The quiet Sunday had erupted into a day of fury, and a Universal Pictures newsreel cameraman recorded it. His film showed the planes strafing at masthead level, so low that the pilots’ faces were seen clearly.

Soon after the first strike, 12 more dive bombers and nine fighters made several runs over the Panay, strafing for 20 minutes. She was riddled with shrapnel from near misses.

The response from the gunboat was immediate but ineffective. Crewmen tore the covers off their weapons, and the .30-caliber machine guns clattered away at the Japanese planes. The salvos were directed by Chief Boatswain’s Mate Ernest Mahlmann, who fought without his trousers. He had been sleeping below decks when the attack started and had no time to get dressed.

Ensign Dennis Biwerse had his clothes stripped off by the bomb blasts, and Lieutenant Tex Anders, the executive officer, was hit in the throat and unable to speak. He wrote instructions in pencil on a bulkhead and navigation chart. Lieutenant C.G. Grazier, the medical officer, heroically tended to the wounded during the ordeal. Suffering great pain and with his face blackened by soot, Commander Hughes lay propped up in the galley doorway. There was no need for him to give orders to his welltrained crew.

The Panay was soon helpless in the water. An oil line had been cut, so no steam could be raised to beach her or use pumps to cope with the rapidly rising water. By 2:05 pm, all power and propulsion were lost.

While the crew strove to save its gunboat, the Japanese raiders paid special attention to the three nearby oil barges. Half a dozen planes dropped bombs, but all missed their targets. Then six dive bombers and nine fighters bore down, bombing and strafing, but the oil barges were able to get underway. The eight gunboat bluejackets who had been drinking beer aboard the Mei Ping helped the panicky Chinese seamen fight fires and move the vessel out of range of the Japanese onslaught.

The Mei Hsia made a valiant effort to ease alongside the stricken Panay and take off survivors, but Hughes and his crew frantically waved her away. They did not want the highly flammable barge alongside while bombs were still falling. The Mei Hsia and Mei Ping then tied up to a pontoon on the southern side of the river, and the Mei An beached on the northern bank.

Less than half an hour after the first bomb hit, it was obvious that the Panay, listing and settling, was doomed. The forward starboard main deck was awash, and there were six feet of water in some compartments. Commander Hughes gave the order to abandon ship, and crewmen started making for shore in the gunboat’s two sampans. While two of the oil barges were being bombed and destroyed, other low-flying enemy planes fired at the sampans, stitching holes in their bottoms and wounding some of the occupants. At 3:05 pm, Ensign Biwerse was the last man to leave the gunboat.

Chief Mahlmann, still without his trousers, and a sailor gallantly returned to the gunboat to retrieve stores and medical supplies. While they were paddling back to the riverbank, two boatloads of Japanese soldiers machine-gunned the Panay, boarded her, and then quickly left. At 3:45 pm, the gunboat rolled over to starboard and slowly slid beneath the water bow first.

The American survivors spent the rest of that day hiding in eight-foot reeds and ankle-deep mud on the riverbank, while the enemy planes continued strafing. “Doc” Grazier did his best to make 16 wounded men comfortable. Because of Commander Hughes’s wounds, Army Captain Frank Roberts, an assistant military attaché who had been aboard the Panay, was put in command of the survivors. His knowledge of the Chinese language and the situation ashore proved indispensable.

With few rations and inadequate clothing for the near freezing nights, the survivors spent two grueling days wandering through swamps and along footpaths and canals to seek refuge away from the river. They were treated kindly by the Chinese and managed to get word of their plight to Admiral Yarnell. They reached the village of Hoshien and were taken aboard the gunboats Oahu and HMS Ladybird.

The Panay was the first American vessel lost to enemy action on the 3,434-mile Yangtze River. Two crewmen and a civilian passenger were killed, and there were 43 casualties, including 11 officers and men seriously wounded.

The loss of the Panay and British vessels, including HMS Ladybird and HMS Bee, and the bombing of the gunboat USS Tutuila at Chungking made headlines in the British and American press. Outrage was widespread. Even the Japanese people and government were aghast, yet the international community failed to take effective action. Remembering the sinking of the 6,650-ton battleship USS Maine in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898, Ambassador Grew at first expected his country to declare war. Prompt Japanese regrets and promises of reparation eventually turned away wrath.

In the Japanese capital, the government of 46-year-old Prince Fumimaro Konoye, the prime minister, was as shaken by the sinkings as were the Americans and the British. An embarrassed Foreign Minister Kiki Hirota took a note to Ambassador Grew expressing regret and offering full restitution for the loss of the Panay. “I am having a very difficult time,” said Hirota. “Things happen unexpectedly.”

The Japanese Navy high command showed its disapproval by dismissing the commander of the 38,200-ton carrier Kaga, who was responsible for the Panay attack. “We have done this to suggest that the Army do likewise and remove Hashimoto from his command,” said Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the naval vice minister, who did not relish doing battle with the U.S. Navy. After spending much time in America, he was aware of the country’s potential military strength. Following an investigation led by Yamamoto, the Japanese government was quick to apologize. Ambassador Grew was intensely relieved, but he wrote prophetically in his diary, “I cannot look into the future with any feeling of serenity.”

President Roosevelt called an immediate meeting of his cabinet, and Navy Secretary Claude Swanson, Vice President John Nance Garner, and Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes urged a declaration of war. “Certainly, war with Japan is inevitable sooner or later,” noted Ickes. “If we have to fight her, isn’t this the best possible time?” FDR replied that the Navy was not ready for war and that the country was unprepared. Senator Harry Ashurst of Arizona told the president that a declaration of war would gain no votes on Capitol Hill. Senator Henrik Shipstead of Minnesota spoke for many when he suggested that American forces in China be withdrawn. “How long are we going to sit there and let these fellows kill American soldiers and sailors and sink our battleships?” he asked.

The president directed Secretary of State Cordell Hull to demand an apology from the Japanese government, secure full compensation, and obtain a guarantee against a repetition of the Yangtze River attacks. FDR also instructed Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. to prepare to seize Japanese assets in the United States if Tokyo did not pay and considered the possibility of an Anglo-American economic blockade.

Intent on clamping a quarantine on Japan, Roosevelt summoned the British ambassador in Washington, Sir Ronald Lindsay, and suggested that the two nations impose a naval blockade that would deprive Japan of vital raw materials. Lindsay protested that such a move would lead to war but cabled London that his “horrified criticisms” had “made little impression upon the president.” The British Admiralty, however, approved FDR’s blockade plan. The president was resolute and briefed the cabinet about his quarantine plan on December 17.

Roosevelt’s stance was strengthened by a report from a court of inquiry called by Admiral Yarnell aboard the cruiser USS Augusta off Shanghai stating that the attack on the Panay had been wanton and ruthless. The president was also informed that a message to the Japanese Combined Fleet had been intercepted and decoded by U.S. naval intelligence indicating that the raid had been deliberately planned by an officer aboard the Kaga.

Foreign Minister Hirota informed Washington that orders had been issued to ensure the future safety of American vessels in Chinese waters and stressed that the commander of the force that had launched the Panay attack had been relieved. An official Japanese inquiry concluded that the attack was accidental and that the British and American vessels had been mistaken for Chinese. The Japanese naval aviators thought they were bombing enemy troops escaping upriver in Chinese merchant ships. Anxious to avoid a war for which it was ill prepared, the U.S. government accepted the “mistake” theory together with an indemnity.

The Japanese apology arrived in Washington on Christmas Eve, 1937, and was officially accepted on Christmas Day. Ambassador Grew believed that the timing was “masterly.” British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s government also gracefully accepted an apology for the sinking of HMS Ladybird.

Though it foreshadowed, generally unnoticed, what was to happen four years later, the Panay incident ended agreeably with a sigh of relief passing across America. It bolstered isolationist efforts to keep America out of war, and a Gallup poll conducted in the second week of January 1938 showed that 70 percent of voters favored a complete withdrawal from China—the Asiatic Fleet, Marines, soldiers, missionaries, medical personnel, and all.

Eventually, on April 22, 1938, the Japanese government complied with Washington’s claim by handing over a check for $2,214,007.36 as “settlement in full” for the Panay, three oil barges, personal losses, and casualties. Tokyo said that if the United States wanted a replacement gunboat for the Panay it would be glad to receive the contract. It also asked if it could salvage the gunboat and oil barges. Washington refused.

Despite the apologies and reparations, the Japanese—led by Emperor Hirohito and Premier Konoye—showed no remorse for the “China incident.” Colonel Hashimoto was not reprimanded and in fact was eventually awarded the Kinshi Kinsho Medal seven weeks after the December 7, 1941, raid on Pearl Harbor. Konoye denounced the Chinese government’s “anti-Japanese movement,” and the offensive continued in China. Aided by heavy naval air bombardment, fresh Japanese divisions assaulted Canton and the cities of Wuchang, Hankow, and Hanyang.

While European nations appeased Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler and America clung to neutrality in the late 1930s, war was a brutal reality in the Far East. Time was running out. In January 1938, Britain and the United States signed a secret agreement to the effect that if the Japanese made any southward move the U.S. Fleet would concentrate at Pearl Harbor while a Royal Navy battle fleet would be based at Singapore. That March, Representative Carl Vinson of Georgia forwarded a bill in Congress to increase the Navy by 20 percent over 10 years. The originator of an act to bring the Navy up to treaty strength, Vinson was the Navy’s best friend on Capitol Hill.

Only a few months after the loss of the Panay, a small-scale but shattering preview of things to come, omens of future threats were evident to perceptive Western observers. Through the spring and summer of 1938, information flowed into the Washington-based Office of Naval Intelligence from attachés in Tokyo and Berlin. The messages from each capital indicated that the Axis powers were arming but did not seek war with the United States. Some of the information received from Japan, however, was less than reassuring.

An April 13 report from the naval minister in Tokyo stated, “The [Japanese] Navy is not building any super-dreadnoughts and has at present no intention of doing so.” In fact, the building of the 72,000-ton Yamato had been started a year earlier, and her sister, the Musashi, was laid down in 1938. In the same report, a Japanese naval officer said, “A Japanese-American war is now out of the question.” However, he further remarked that “the present world situation may lead to a war between democratic and totalitarian states, and in this Japan would oppose America in the Pacific.” The officer “felt no doubt about the ultimate victory of the Japanese Navy.”

A June 1938 intelligence report from Tokyo declared, “The Japanese are going places. For the present, the United States has not much to fear. But when Japan has consolidated her gains in China several years hence, a clash with her is inevitable.”

In April 1938, meanwhile, Admiral Yarnell’s 1932 exploit had been repeated by Vice Admiral Ernest J. King, commander of the Aircraft Battle Force, as part of Fleet Problem 14. Taking advantage of foul weather, planes from the unnoticed carrier USS Saratoga north of Oahu made a successful mock raid on Pearl Harbor. After each of the war games, judges concluded that if the attacks had been real they would have succeeded. However, few people took the maneuvers seriously; they were just interesting exercises.

The growing list of Japanese war crimes in China had prompted a call from President Roosevelt early in 1938 for a “moral embargo” of Japan by American arms exporters, and this was made a policy that July after the bombardment of Canton. It was the first expression of American displeasure with Japan, and it proved moderately effective.

Secretary Hull sent a long letter in October protesting Japanese activities in China, and Tokyo responded the following month. Premier Konoye declared a “new order in East Asia” whereby Japan planned to entrench its domination of Manchuria and China regardless of anyone else’s “rights.” East-West relations inevitably worsened, and just over three years later the Imperial Japanese Navy sent its carrier planes against the U.S. Pacific Fleet, thrusting America into World War II.

Well written and accurate account of events. My Uncle Robert Breen was assigned to the Gun Boat USS Asheville. The Asheville has a interesting history… Unfortunately, she too was plagued with engine problems, that lead to her demise on 02MAR42