Raymond E. Bell, Jr.

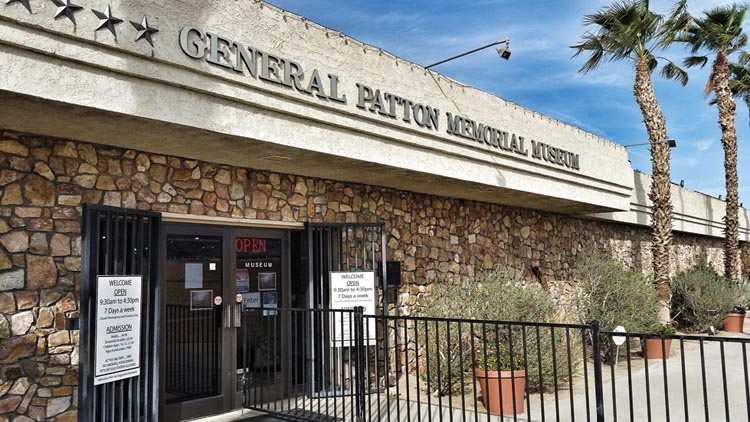

Thirty miles east of Indio, California, is the General Patton Memorial Museum, a special museum dedicated to General George S. Patton, Jr., who was responsible for determining the location of and establishing the Army’s Desert Training Center in southern California and parts of Nevada and Arizona. He chose a vast area of high plateau desert which he felt mirrored the terrain characteristics of North Africa where it was determined that American troops likely would see combat before the European continent itself was invaded.

The General Patton Memorial Museum is built around the two-year desert warfare training experience but encompasses a great deal more which is expressed in literature as “A Military History Museum Honoring America’s Veterans.” Outside walls consisting of special bricks honoring participants in conflicts to include the world wars, Vietnam, and Korea frame the building’s entrance and make a statement about the museum’s inclusiveness.

The museum’s general appeal for visitors therefore spreads to those interested in military exhibits extending from World War I to the present day. What makes the museum unique, however, is its coverage of the military activities that took part in the desert training area from its establishment in 1942 to its inactivation in 1944.

On February 5, 1942, the War Department approved the creation of a large area for specialized desert training, with the implication that conditions would be harsh to reflect those which might be found in North Africa. As noted, Patton then surveyed parts of southeast California and western Arizona for suitable sites that would offer the terrain and weather conditions necessary in which to conduct appropriate training.

In Before the Colors Fade, by Fred Ayer, Jr., a Patton nephew, described those conditions under which Patton wanted to train his men to fight effectively. Ayer described the temperature in summer as reaching 120 degrees Fahrenheit, with a brutal sun bearing down on the troops and no trees present to provide shade.

The dust from blinding storms also made it uncomfortable for the troops, and flash floods roared out of the mountains through deep gullies, posing a serious danger to unwary soldiers. Snakes and scorpions were in abundance. Boots and sleeping bags had to be closely examined for the scorpions before being occupied, while trips to the latrines at night held the danger of rattlesnake encounters.

Patton was only present in the area for four months before he went off to prepare for the November 1942 invasion of Morocco. But during his time at the training center, Patton drove himself relentlessly, sharing the hardships with his men. But, according to Ayer, the men came out “tough, dehydrated and leanly stripped of all excess flesh. They were as nearly ready combat-trained as is possible for troops who have not yet been fired upon in anger.”

Standing outside the air-conditioned museum building is a large statue of General Patton and his dog Willie. In a way, the size of the statue characterizes the vastness of Patton’s undertaking in choosing and laying out the training area; for almost as far as one can see from the museum it is endless and monotonous terrain.

To begin one’s visit, there is a 45-minute film which is an excellent introduction to the exhibits. The film gives context to what little is generally known about the activities that took place at the site in the early stages of the United States’ participation in World War II. The presentation helps the visitor understand the importance of the desert training area, the development of the center, and the conditions under which the troops trained. Soldiers training there, for example, were allocated only one canteen of water a day, which was certainly less than what today’s troops fighting in similar conditions are allotted.

A wide range of exhibits beckon. One of the more unique is the piano which was donated for entertainment at the Camp Coxcomb officer’s club by Patton’s wife, Beatrice. Outside, the tank park has vehicles from World War II to Desert Storm, including an M4 Sherman. Wall tablets and panels display memorabilia and photos that explain different aspects of training and camp life. Two rooms are dedicated to Medal of Honor recipients and the World War II Holocaust. The gift shop offers a plethora of armored vehicle models and books on military subjects.

Although the focus of the museum is on the DTC, the displays are not limited to training in the area, which began in the spring of 1942. In addition to the DTC focus, weapons and equipment from the various wars are displayed inside. A sign at the entrance to the park warns of rattlesnakes and reminds visitors of the desert environment which soldiers training in that environment encountered.

While General Patton’s stay at the DTC was short, the museum named for him perpetuates the efforts he made to train soldiers to fight in the desert, and beyond. For anyone with an interest in World War II and Patton, a visit to the museum is an enlightening one.

The museum is readily accessible from the highway and its presence is a welcome stop at Chiriaco Summit for anyone traveling east on Interstate 10 from the town of Indio.

When one sees the statue of General Patton and Willie beckoning from Interstate 10, one is compelled to stop and visit the museum bearing the general’s name.

GENERAL PATTON MEMORIAL MUSEUM

Interstate 10, Exit # 173, (Chiriaco Summit Exit) California

(760) 227-3483

www.generalpattonmuseum.com

Hours: Open 7 days a week – 9:30 am – 4:30 pm

Admission: By donation. Active-duty military enter free.