By Charles Hilbert

As converging columns of British and native infantry surrounded the inner palace of his capital, Seringapatam, Tipu Sultan did not hesitate. Around him all was chaos: the crack of muskets, the screams of dying men, the exultant shouts of their conquerors, the acrid smell of black powder, the confused mob of fugitives milling around the mounted sultan in the confined space between the inner and outer ramparts, all under the blazing heat of the Indian sun.

It would have been easy for him to spur his charger forward through the outer defenses to seek safety in the darkness of an impenetrable jungle, or he could have declared himself and surrendered to the approaching troopers. But the transient existence of a hunted fugitive was not acceptable to the Tiger of Mysore, nor was the notion of an honorable captivity. Without a second thought, he rode toward the Water Gate and the inner palace, there to make his last stand.

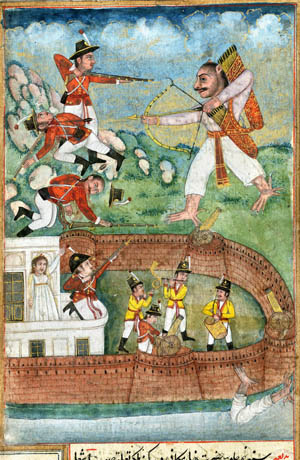

Tipu hated the British. He had been fighting them for 30 years. As a young cavalry commander in the army of his father, Hyder Ali, during the First Mysore War, he had led a lightning raid right up to the gates of Madras, capital of the Carnatic, which caused the panicked British governor to hastily embark on a short cruise in a rather small boat.

That war had ended favorably for Hyder Ali with a return to the prewar status quo, but animosities remained, and by 1779 Hyder and Tipu were again at war with the British East India Company. In 1780, they annihilated a contingent of 3,500 sepoys and Englishmen at Polilur, and though Hyder died of cancer two years later, Tipu fought the company to a standstill, signing the treaty of Mangalore in 1784, which once again restored the prewar status quo. To commemorate his victory at Polilur, Tipu made himself the present of a life-sized, mechanical, wooden tiger savaging a supine sepoy, complete with a bellows that produced roars and screams of pain.

Tipu experienced a serious setback in 1792 when Lord Charles Cornwallis, governor general of India, surrounded Seringapatam and forced him to give up half his territory. But the Sultan of Mysore was no quitter. He tried to arrange alliances with various Indian powers and with the French under King Louis XVI, and then Napoleon Bonaparte. This last bit of diplomacy alarmed the new governor general, Richard Wellesley, Lord Mornington, who had imperialistic plans of his own.

Tipu and Mornington spent the fall and early winter of 1798 exchanging letters, the former expressing his friendship for the English and hatred of the French, the latter his desire for peaceful relations between the company and Mysore. At the same time, both prepared for war. On February 3, 1799, Mornington ordered his forces to move against Mysore.

He had prepared a two-pronged attack. The Madras, or Grand Army, under the command of General George Harris assembled at Vellore, 100 miles west of Madras and less than 200 miles east of Seringapatam. The Bombay Army, commanded by General James Stuart, was marshaled at Cananore, about 100 miles to the west of Tipu’s capital.

Cornwallis’s campaign against Tipu eight years before had been plagued by supply problems. This time the English were taking no chances. When the 21,000 men of the Madras Army marched out of Vellore on February 11, they were accompanied by a crowd of camp followers 10 times their number, leading a noisy menagerie of more than 100,000 oxen, horses, donkeys, and elephants carrying supplies, ammunition, and ordnance. They did not make good progress. On February 13, Lord Mornington received a letter from Tipu asking him to send an ambassador to Mysore to discuss the situation. He dispatched his answer to Harris with orders to send it on to Tipu when the Madras Army crossed the boundary of Mysore.

Two weeks later, Harris was still plodding along when the Bombay Army, 6,500 men under Stuart, left Cananore. Expecting the British to attempt a repeat of their 1792 invasion, Tipu took up a position east of Seringapatam at Madur on the road to Bangalore, sending out raiding parties that devastated the countryside, burning anything that could be of use to the enemy.

The Nizam of Hyderabad, Tipu’s neighbor to the northeast, having lately allied himself with the English, sent 16,000 men to join the Madras Army. This detachment was under the command of the Nizam’s son, Meer Alum, but really took its orders from Lord Mornington’s 29 year-old brother, Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington. They met the Madras Army at Karimungalum, not far from Tipu’s eastern border, on February 28. On the same day, apprised by his spies of the advance of the Bombay Army, Tipu left Madur and marched west to attack Stuart.

Stuart’s advance post, commanded by Colonel John Montresor, was at Seedasere, about seven miles west of Periapatam and about 50 miles west of Tipu’s capital; the main body of his army was stationed at two towns, eight and 12 miles to the rear of the advance force. While Tipu was advancing on Stuart, Harris reached Ryacotta at the border of Mysore on March 4, from whence he dispatched Mornington’s letter to Tipu, which informed the potentate that his future correspondence should be addressed to Harris, who had full powers to negotiate a settlement.

The next day, Stuart’s scouts observed the arrival of Tipu’s army, which encamped between Periapatam and Seedasere. Stuart sent a battalion of sepoys to reinforce Seedasere. That same day, Harris crossed the Mysore frontier and began to capture various hill forts.

On the morning of February 6, barely visible through the mist and the thick woods that surrounded Seedasere, 12,000 of Tipu’s men gradually took up positions around the town. At 10 am, they simultaneously attacked the front and rear of Montresor’s position. Led by their British officers, the company’s sepoys fired disciplined volleys that cut down the advancing Mysore troops. By 2:30 pm, Stuart had reached the battlefield and attacked the rear of the force that had attacked the rear of the advance post. After a 30-minute firefight, the Mysoreans withdrew, and Stuart advanced to relive Montresor. By 3:20 pm, Tipu was retreating, and Stuart withdrew to Seedapore, 12 miles to the rear of the advance post, to secure his line of supply. “I myself saw at least Three Hundred men killed or mortally wounded laying on the Road and in different parts of the Jungle, where a great slaughter of the Enemy took place,” wrote Major Lachlan Macquarie, one of Stuart’s staff officers. Tipu returned to Periapatam. He left on February 11 and marched toward Seringapatam.

Harris’s huge army was advancing slowly, making many stops on the way. On March 14, his troops encamped within sight of Bangalore. Fearing that the British would make this their base of operations, as they had done in the previous war, Tipu’s cavalry commander ordered his men to burn the town and the surrounding villages. But Harris had other plans. He turned south on March 16 and took the road to Kaunkanully. Tipu, expecting Harris to take the northern and more direct road to Seringapatam, again took up position at Madur on the Bangalore road and laid waste the countryside along that route; however, he neglected to do the same to the southern road, upon which Harris was now marching. Learning of Harris’s southward movement, Tipu turned to his right and took up a strong position on the west bank of the Madur River on March 18. A detachment of the Madras Army arrived at Kaunkanully, a few miles east of Tipu’s army, on March 21, just in time to prevent Tipu’s men from draining the local reservoirs, or tanks. Two days later, Tipu inexplicably left the Madur River and made camp at Malavelly, about 30 miles east of Seringapatam. The next day, Harris crossed the river and camped on the ground lately vacated by Tipu. On March 26, the Madras Army halted in sight of Malavelly.

As the sun rose on the morning of March 27, Harris’s advance guard, five regiments of cavalry under Maj. Gen. John Floyd, came in sight of Tipu’s cavalry on the right, about a mile in front of Malavelly. Tipu’s infantry was drawn up on the high ground behind the town. Floyd could see them dragging cannons into position on their right.

Wellesley and Floyd were ordered to advance against Tipu’s right, while Harris led the rest of the army through Malavelly against the center of the Mysore line. As Wellesley advanced, supported by Floyd’s cavalry, Tipu’s gunners and infantry withdrew to another ridge in the rear of their original position. Seeing this, Harris ordered his quartermaster general, Colonel John Richardson, to prepare the day’s encampment. At this moment, Tipu’s guns opened fire at a range of 2,000 yards. Richardson carried on, and Colonel John Sherbrooke was ordered forward to take a village in front of the left of the enemy line. Sherbrook left the 25th Dragoons in the village to keep an eye on a large detachment of Tipu’s cavalry that threatened the British right. Harris then formed line of battle with Wellesley and Floyd on the left and Maj. Gen. David Baird on the right.

As the advancing British line crossed the first ridge, a gap opened between Baird and Wellesley. Hoping to exploit this tactical opportunity, Tipu immediately led his cavalry forward in two columns to the left and right of Baird’s position. The left column reached Baird first. He ordered three companies of the 74th (Highland) Regiment of Foot to fire and fall back, but after they fired they impulsively charged instead.

With the 74th out in front, the right column of Tipu’s cavalry charged their exposed flank. Baird spurred his horse and rode out between the lines to halt their impetuous advance. As Baird reformed the 74th, the 12th and the Scots Brigade on his right halted the advance of Tipu’s troopers.

Most of the Mysore cavalry wheeled to their left and rode along the front of the British line, exposed to the fire of the company’s sepoys; a few galloped through the interval between Baird and the brigade to his right. They charged straight at Harris and his staff, somewhat to the rear of the British line, and the Mysore troopers and British officers fired on each other with their pistols.

At the same time, approximately 2,000 of Tipu’s foot soldiers advanced in column against Wellesley and the Nizam’s troops. At 60 yards, Tipu’s men fired. Wellesley charged with the bayonet, and Floyd led a cavalry charge. The sudden impetus compelled the Mysore column to retreat. Harris did not pursue. The company lost 61 men killed, while Tipu left behind a thousand dead, scattered across the field of battle.

Back in 1792, Cornwallis had approached Seringapatam on the north side of the River Cauvery and camped at the village of Arakery on the north bank of the river. Expecting Harris to do the same, Tipu withdrew in the direction of Arakery. But Harris intended to approach Tipu’s capital from the southern side of the Cauvery. Once again he took the southern route, which, since Tipu expected him to take the northern and more direct road to Seringapatam, remained untouched and provided food and forage for the Madras Army.

Marching out of Malavelly on March 28, Harris sent a force to reconnoiter the ford over the Cauvery at the village of Sosilay, some miles to the southwest of his position and 15 miles southeast of Seringapatam. They returned that night and reported that the ford was practicable. The British reached Sosilay the next day and, after reassuring the locals that no harm would come to them, began crossing the wide Cauvery via a ford where the water was only three feet deep. It took two days for Harris to move the large column to the southern bank of the Cauvery, while Tipu waited for him on the wrong side of the river. When Tipu learned that he had been outmaneuvered, he assembled his whole staff. “We have arrived at our last stage; what is your determination?” “To die with you,” was the unanimous reply.

Tipu sent his infantry and artillery into Seringapatam and, on March 31, crossed to the southern bank of the Cauvery with his mounted troops. The huge Madras Army lumbered on, making about seven miles a day. Tipu shadowed them with his cavalry. He watched from a hilltop as they made camp five miles from his capital on the evening of April 2.

Tipu ordered his infantry and 20 guns to cross the river and join him, intending to occupy some high ground four miles south of the city. Something changed his mind, and he withdrew to Seringapatam, built on an island in the middle of the Cauvery River. Tipu’s gardens, including the tomb of his father, Hyder Ali, formed a triangle at the eastern end; the town lay in the center, and his fortress and palace occupied the western point.

For the next two days, the large column crawled eastward across the heights lately vacated by the Sultan of Mysore. On the evening of April 4, the column halted. Before it was a small grove of betel nut trees known as the Sultanpettah tope. The betel nut being an important ingredient in certain religious ceremonies, great care was taken to irrigate the trees, so the Sultanpettah tope was crisscrossed by wide ditches. Concealed among the tall, bamboo-like palms and irrigation ditches was a large body of Mysorean troops, including rocket men. Baird was ordered to clear the tope, and at 11 am on April 4 he advanced. Tipu’s men withdrew. Baird returned to camp, the rocket men returned to the tope, and Tipu’s infantry took up posts in a ruined village to the left of the tope.

On April 5, the army marched by the left, keeping under the ridges to the south and west of Sultanpettah to avoid the topes, which afforded cover for the enemy’s rocket men and from whence a number of rockets were thrown without effect. After a short march, the army took up its ground opposite the west face of the fort of Seringapatam at the distance of 3,500 yards.

The army encamped facing east, its right anchored on high ground, its left protected by an aqueduct that lay between the army and the city and curved around behind the rear of the encampment, affording an extra defense against any surprise attacks by a desperate enemy.

That night, Harris ordered Wellesley to clear out the tope once and for all. Colonel Robert Shaw was directed to take the ruins of a village northwest of the tope and 40 yards short of the aqueduct. At sunset Wellesley and Shaw advanced. Shaw carried the village but was fired upon by enemy infantry covered by the aqueduct. Wellesley’s company advanced into the black night, highlighted from behind by the lights of the British camp. Disordered by the deep irrigation ditches and dense vegetation as rockets exploded and musket balls slapped into the foliage around them, a dozen men wandered into the enemy’s position and were taken to the fort to be strangled later. The future Duke of Wellington got lost. After several hours of stumbling in the dark, he returned to camp.

At 9 am the next day, as Major Alexander Beatson relates, “Colonel Wellesley, with the Scotch brigade, two battalions of sepoys, and four guns, advanced to the attack of the tope; from which the enemy fired…. Their fire was returned by a few discharges of grape from the field pieces … parties were detached to take the enemy in flank, which soon threw them into confusion, and obliged them to retire with precipitation.” At the same time, Shaw advanced from the village and cleared the aqueduct in his front while another detachment under Colonel William Wallace secured the rest of the line of the aqueduct to Shaw’s left, causing the enemy to withdraw from their forward positions. Tipu’s cavalry left the island and took the road to Periapatam.

The next day, Harris sent Floyd and half the army to link up with Stuart at Periapatam. Tipu fortified a powder mill on the south bank of the Cauvery a little to the west of the end of the island, and he built entrenchments from the powder mill to the Periapatam bridge, which was near the southwest angle of the fort.

Two days later, Harris received a letter from Tipu, “I have adhered firmly to treaties. What, then, is the meaning of the advance of the English armies and the occurrence of hostilities?” Harris informed him that, in accordance with the terms offered in Mornington’s last letter, the price of peace would be half his kingdom, four of his sons as hostages, and a large indemnity.

On April 10, Floyd rendezvoused with Stuart at Periapatam and the next day set out for Seringapatam. “About 5,000 of the Enemy’s Horse made their appearance soon after we marched, within about half a mile of our Line on our Right Flank,” wrote Major Lachlan Macquarie. “They threw some Rockets at the Nizam’s Horse but did not attempt to attack them; they however hung the whole of our march on our Flanks and Rear.”

For the next two days the Bombay Army marched slowly, dragging its artillery pieces over rough ground. On April 13, the army found itself hard pressed by the enemy, which attacked the rear guard as it negotiated a narrow pass. Mysorean cavalrymen brazenly rode up to the rear guard and fired musket rounds while rockets burst among the sepoys.

Marching at dawn on April 14, the combined forces arrived at Seringapatam in the early evening. “We encamped immediately in the Rear of the Grand Army,” wrote Macquarie. “We were harassed during the whole of this Day’s march as usual by the enemy’s Horse.” On April 16, the Bombay Army crossed the Cauvery and took up a strong position on the north side of the river about 1,800 yards from the fort at Seringapatam. The Bombay Army’s right was anchored on the river, and its left extended to high ground facing east toward the fort. Floyd and his men got little rest, now being sent off to cover foraging parties.

Nineteenth-century tactics required that a breach be made in the fortifications of a walled city for infantry troops to make an assault. This was achieved by a slow advance of artillery batteries through a series of parallel trenches connected by zigzag trenches. According to Beatson, the southwest wall of the “north-west angle of the fort … a line nearly five hundred yards in length … exposed to a destructive enfilading fire from the north side of the river … totally exposed to breaching batteries from the westward,” would be the site of the breach, the Cauvery at that point being easily fordable.

On the night of April 17, the British established a battery of six 18-pounders 800 yards from the southwest angle of the fort. Tipu sent men down into the mostly dry bed of the Cauvery. From the cover of the bank they fired upon their enemies, who replied with grape shot, canvas bags full of lead balls that turned their two 6-pounders into giant shotguns. After an hour of this rather uneven conflict, the Mysorean infantry withdrew into the fort. The long-range firefight resumed the next day, Tipu’s snipers firing from the riverbed and his cannons from the fort, while the British continued to rake their enemies in the Cauvery with grape. During the day, Floyd returned to the camp, having rounded up quantities of grain and cattle. As the 18-pounders were being wrestled into position that night near the south bank of the Cauvery, Tipu’s cavalry and rocket men attacked the rear of the Bombay Army and were driven off by grape shot.

Dawn of April 19 saw the 18-pounders in action against the southwest bastion of the fort. The following day these cannons were turned against Tipu’s men in the powder mill, and by early evening the position was taken and work begun on the first parallel trench. That night Harris received another letter from Tipu offering to negotiate. Two days later, Tipu received Harris’ reply, reiterating his demands for hostages and the payment of a large sum of gold within 24 hours.

To position an enfilading battery that would be able to fire on the walls of the fort from the northwest, from which position their shot would travel the inside length of the walls, exposing the defenders to fire from their right, Montresor led the 74th Regiment of Highlanders against the village of Agarum, close to the north bank of the Cauvery. The fighting there was intense. The 74th carried the village but was driven out by a heavy fire of grape from the fort, followed by a general attack on the position; they returned, drove out the defenders, and spent the rest of the night warding off their relentless foes. By daybreak the attacks petered out, and the rising sun revealed numbers of the enemy dead lying close to the British position, among them several Frenchmen who had led the attacks. Tipu had long employed French mercenaries, and there were about 450 present at the final Battle of Seringapatam. During the night, the British emplaced a six-gun battery at the mill.

The next three days saw more attacks on the rear of the Bombay Army, while the 18-pounders and the enfilading battery kept up a heavy fire against the fort, which was answered just as enthusiastically by Tipu’s artillery. The artillery duel continued, with the British adding more cannons, and the firing from the fort slowly slackening as the British advanced their approach trenches, adding howitzers that threw shells over the walls into the fort.

On April 26, the picquets of the Bombay Army were attacked at 4 am by a fire of muskets and rockets. By dawn, their attackers were driven away, and the bombardment of the fort continued. That evening, troops of the Madras Army took Tipu’s advance positions south of the Cauvery in front of the southwest wall of the fort. Saturday saw more harassing attacks on the Bombay Army, while Tipu’s infantry attempted to retake the positions lost the day before, without success. The British emplaced more artillery batteries. A severe bombardment was opened on the fort, which was returned, and for the next three days the British and Mysorean artillery slugged it out. On April 29, Tipu wrote to Harris one last time, offering to send ambassadors. Harris replied that he was “prepared to reject any ambassadors who did not come fully prepared to agree to all the conditions of the treaty, and bring the money with them.” As Tipu continued his ineffectual correspondence, the British trenches inched closer and closer to the fort.

By May 1, with more British batteries emplaced almost daily, the fort’s guns near the intended breach were silenced. Fifty-two guns opened on the fort on May 2. “By Noon a very large Gap was made in the Wall and every shot striking the bottom of it brought part of it down … by Sunset a very large Breach was made in the South West Curtain,” wrote Macquarie.

On May 3 the breach in the southwest angle of the wall was deemed practicable. The order to attack the next day was given to Maj. Gen. David Baird, who was cranky and ill tempered at the best of times, and who had spent several years as Tipu’s prisoner, having been captured at the Battle of Polilur in 1780. The passage of time had not diminished his implacable hatred of the Tiger of Mysore. That night Lieutenants James Farquhar and John Lalor waded the Cauvery, jamming stakes in the river bottom to mark the path that the attacking columns should take. The troops destined for the assault were stationed in the trenches before daybreak. Baird was among them, assuring those who had been captured with him years before and had suffered alongside him in Tipu’s dungeons that they would soon be able to settle old scores.

Starting at dawn the next day, the breach was blasted again. At 10 am, a detachment of Tipu’s cavalry attacked the rear of the Bombay Army, but was driven off. A general bombardment of the town and fort at Seringapatam was begun. Beatson mentions that Tipu’s astrologers had warned him that May 4, 1799, would be “an inauspicious day.” As his cavalry was attacking the Bombay Army, Tipu was distributing largesse among the Brahmins as a spiritual defense against the ill-omened day. His spies and several of his officers, including Syed Goffar who commanded near the breach, informed him of a large number of the enemy in the trenches. For some reason, Tipu considered this unlikely and went off to have lunch.

Baird had divided his force into two columns, which would separate once they had entered the breach: the left, under command of Lt. Col. James Dunlop, would take the northern rampart; the right, commanded by Colonel Sherbrooke, would advance along the southern wall; they would meet at the eastern rampart and thus surround the inner town and palace.

As recorded in the Regimental History of the 73rd (Highland) Regiment of Foot: “At 1 pm by Baird’s watch, the huge Scot stood, his sweat-soddened uniform stuck to him as he climbed out of the trench; he drew his regimental claymore and bellowed, ‘Now, my brave fellows, follow me and prove yourselves worthy of the name British soldiers!’” Approximately 2,000 Europeans and 1,800 sepoys clambered out of the trenches and rushed the breach, the leading companies ordered to use the bayonet and refrain from firing unless it was absolutely necessary. Each column was preceded by a forlorn hope composed of a sergeant and a dozen Europeans. They were greeted by an intense fire of rockets and muskets.

Baird had decided to lead the left column, but the heavy fire of the enemy caused this column to incline away from the marked ford. The soldiers stumbled into deeper water under the high bank of the river, which protected them from the flaming rockets and spattering bullets. Baird, impatient to get to grips with his old enemy, leaped into the Cauvery and headed straight for the breach while leaden musket balls whizzed and splashed around him. He was hot on the heels of the forlorn hope. The warriors of Mysore met their attackers head on.

Macquarie tells how Dunlop, at the head of his troops, crossed swords with one of Tipu’s officers. He parried his opponent’s cut “and instantly making a cut with his sword at the Sirdar across the Breast, laid it open, and wounded him mortally.” Striking back as he fell, the Sirdar nearly cut off Dunlop’s right hand. Spouting blood, the colonel gained the top of the breach while his men bayoneted the recumbent and moribund Sirdar.

Six minutes after the commencement of the assault, the British colors waved in the breach, but only for a moment. “A sudden, sweeping fire from the inner wall came like a lightning blast, and exterminated the living mass,” wrote Lieutenant Richard Bayly. “Others crowded from behind, and again the flag was planted.”

“Colonel Sherbrooke was knocked down by a spent musket ball as he mounted the breach, but quickly recovered,” recalled Macquarie. Company troops now filled the 100-foot space between the ruined walls. After a moment’s delay in crossing an unexpected water-filled ditch, Baird ordered the columns forward. He led the right along the southern rampart while Dunlop, having collapsed from loss of blood, was carried off the field.

Tipu was having lunch in a small gateway under the northern rampart, which had been walled up years before, where he had been headquartered for the last two weeks. Hearing the sound of fighting, he left his unfinished repast and called for his sword and fusils. As he was strapping on his sword, someone ran up to him and told him that his friend Syed Goffar had been killed at the breach. Noting that Goffar was never afraid of death, the sultan instructed that Mahommed Cassim should take command of his division. Then, followed by four men who carried his fusils and by a fifth who carried a blunderbuss, Tipu mounted the northern rampart and headed toward the breach.

Many transverse walls obstructed the advance of the left column. Although the light infantry, led by Captain Thomas Woodhall, had penetrated into the town and was now flanking the transverse walls, the fighting was heavy, and all the officers of the left column were either killed or wounded. Lieutenant Farquhar took command and was immediately shot dead.

Tipu stood behind one of these transverse walls and fired at the advancing company troops as his servants loaded for him. Three or four Englishmen fell by his hand, but the rest came on relentlessly. Faced by the advancing troops and flanked by the light infantry, those of Tipu’s men who had not fallen began to flee. Unable to rally them, Tipu had no choice but to retreat, fighting from one transverse wall to the next with a small group of his most determined adherents. “A short fat officer” defended every traverse, according to the Regimental History of the 73rd (Highland) Regiment. The officer himself kept firing loaded weapons that were handed to him by his hunting servants. One of those who fell by this accurate fire was Lalor of the King’s 73rd. This description matches the observations of Allen, who would later be involved in the search for the sultan. Tipu “was of low stature, corpulent,” he wrote.

The right column led by Baird encountered less resistance, possibly because the Mysorean soldiers there did not have the encouragement of their sultan’s presence to inspire them. “We had a distinct view of every movement,” wrote Beatson. “The enemy retreated the moment our men advanced upon them with the bayonet … many of the fugitives in attempting to escape from the fort, by lowering themselves down with their turbans from the walls … were dashed to pieces on the rocky bottom of the ditch.”

Reluctantly retreating along the northern rampart, Tipu mounted his horse and rode eastward atop the rampart. As he rode down a ramp near the Water Gate, he was struck in the right side by a musket ball. This he seems to have barely noticed. To his right the Water Gate led to the inner town and his palace, where his family awaited the outcome of the battle. He headed toward the gate, which was crowded with fugitives. As he attempted to pass through, the left column caught up with him and at the same time the light infantry reached the interior of the gate. Tipu was now trapped between two hostile forces. The British opened fire; the close-packed soldiers and civilians of Seringapatam stumbled and fell as clouds of smoke rolled over them. Bullets ripped through Tipu’s fine garments. The gate was immediately filled with dead and dying. Tipu’s last remaining servant, Rajah Cawn, advised him to announce himself and be taken alive. “Are you mad? Be silent!” shouted the wounded sultan. Another burst of fire and Tipu’s horse was hit, and Rajah Cawn took a bullet in the leg. Horse, sultan, and faithful servant collapsed onto a pile of writhing bodies.

The Tiger of Mysore lay in the gateway upon a heap of the slain. As the British soldiers entered, one of them approached him and reached forward to despoil him of his rich accouterments. The bleeding, moribund sultan struck with what remained of his strength, cutting open the Englishman’s knee with his sword. The soldier stepped back, took aim, and shot him in the head.

The left and right columns met at the eastern rampart. The city had fallen. “The fortress now became one wild scene of plunder and confusion,” wrote Bayly. “The troops had filled their muskets, caps, and pockets with zechins, pagodas, rupees, and ingots of gold. One of our grenadiers, by name Platt, deposited in my hands, to the amount of fifteen hundred pounds’ worth of the precious metals, which in six months afterwards he had dissipated in drinking, horse-racing, cock-fighting, and gambling.”

The sultan’s palace was surrounded. Baird sent Major Allen with an offer of protection to Tipu and his family if he would surrender unconditionally on the spot, or “the palace would be instantly assaulted, and every man put to the sword.” Allen was admitted, and the sons of Tipu surrendered themselves, but they denied any knowledge of their father’s whereabouts. Baird, although disinclined to believe them, sent them off safely to the British camp and then tore through the palace in search of his old enemy. The governor of the palace, after some serious threatening by Baird, revealed the last known position of Tipu Sultan. He led Baird, Allen, and others to the Water Gate, where a pile of approximately 300 bloodstained corpses filled the archway.

At dusk the bodies were dragged out one by one and examined by the governor. This was a lengthy process, and as the evening darkened, torches were lit. Major Allen and the governor entered the gateway and continued the search in the flickering light. They came upon Tipu’s servant, who was lying wounded under the sultan’s palanquin. He directed them to the spot where Tipu had made his last stand. The body was carried out and recognized as the sultan.

“His eyes were open, and the body was so warm that for a few moments Colonel Wellesley and myself were doubtful whether he was not alive: on feeling his pulse and heart, that doubt was removed,” wrote Allen. “He had four wounds, three in the body, and one in the temple; the ball having entered a little above the right ear, and lodged in the cheek.” The sultan’s body was carried to the palace, and the next day Baird, in an effort to stop the looting, ordered that any man found doing so would be hanged. The looting stopped.

As a result of the fall of Seringapatam, Lord Mornington was made Marquess Wellesley; he appointed his brother the governor of Mysore. Baird, who was not pleased about Colonel Wellesley’s new command, was shunted off to Dinapore in Bengal. Tipu’s mechanical tiger (along with anything else of value) was shipped to England, where it and its unfortunate victim now silently occupy a case in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

The plundered Treasure, Gold and Other valuables must still be with British families, Descendents of East India Company soldiers. They must atleast return them to British Museum Or Indian high commission