By John E. Spindler

Even in the dark days of March 1945, when the Third Reich was on the brink of collapse, its troops managed to exhibit that grim humor that enables frontline soldiers to endure the horrors of battle. As the panzer crews of mighty Tiger II tanks rumbled forward in the last German offensive of World War II in eastern Hungary, they joked about the difficulties they were having coming to grips with the enemy. A few of the 68-ton King Tigers sank up to their turrets in the mud produced by an early spring thaw. Making light of the situation, tank commanders quipped that they were steering tanks, not U-boats.

The Soviet forces gathering on the Oder River in early 1945 seemed not to bother Adolf Hitler. The German leader became fixed on the need to protect the Hungarian oilfields from Red Army tank and rifle units that had encircled Budapest in late December 1944. Hitler had sent the IV SS Panzer Corps against the forces threatening Budapest in three consecutive counterattacks in January 1945 that were known collectively as the Konrad Offensives. But the tenacious Soviet forces had repulsed each assault. On February 13, the city fell to the soldiers of Marshal Rodion Malinovsky’s 2nd Ukrainian Front.

The Hungarian oilfields at Nagykaniscza constituted the last major petroleum resources available to Germany. By early 1945, the Austrian and Hungarian oilfields furnished 80 percent of the oil for the German armed forces. Despite the setbacks of January, Hitler devised a new offensive called Operation Fruhlingserwachen (Spring Awakening) that had both economic and military objectives. Hitler wanted to stem the Soviet tide in Hungary. He envisioned a larger offensive that would roll back the gains of Marshal Fyodor Tolbukhin’s 3rd Ukrainian Front in Hungary. If all went according to plan, the Germans would inflict severe distress on the Russian marshal and his forces in the upcoming campaign. Hitler hoped that his panzer forces would be able to establish bridgeheads over the Danube River and perhaps even retake Budapest. In so doing, the Germans would secure the oil resources needed to feed their war machine.

Although Operation Spring Awakening officially began on March 6, 1945, the planning began as early as January. The Supreme High Command of the German Army issued orders on January 16 to SS-Oberfruppenfuhrer Sepp Dietrich to bring his Sixth Panzer Army back to Germany from the Ardennes region to rest and refit for a new operation. Although Dietrich’s command is commonly referred to as the Sixth SS Panzer Army, it was not officially known as such until it was transferred to the Waffen SS on April 2, 1945.

Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army comprised Generalleutnant Hermann Preiss’s I SS Panzer Corps and Generalleutnant Willi Bittrich’s II SS Panzer Corps. Preiss’s corps was com- posed of the 1st SS and 12th SS Panzer Divisions, and Bittrich’s corps was composed of the 2nd SS and 9th SS Panzer Divisions. To bring these battered units up to standard strength for an SS panzer division, the commanders filled the depleted ranks with raw recruits and support personnel from the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine. Unfortunately, time and fuel were in short supply, so the replacement personnel received no combat training. Nevertheless, the four panzer divisions did receive nearly all of the arms and vehicle production they needed to build up their tank, assault gun, and tank destroyer requirements. In the end, the Germans amassed 240,000 troops, 500 tanks, 173 assault guns, and 900 combat aircraft for the offensive.

Hitler and his advisers planned to make the main attack for Operation Spring Awak- ening with General Otto Wohler’s Army Group South. Wohler would have plenty of hitting power. His command would consist of General Hermann Balck’s Sixth Army, Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army, and the Hungarian 8th Corps. Wohler had a total of 10 panzer and five infantry divisions to hurl against the 3rd Ukrainian Front.

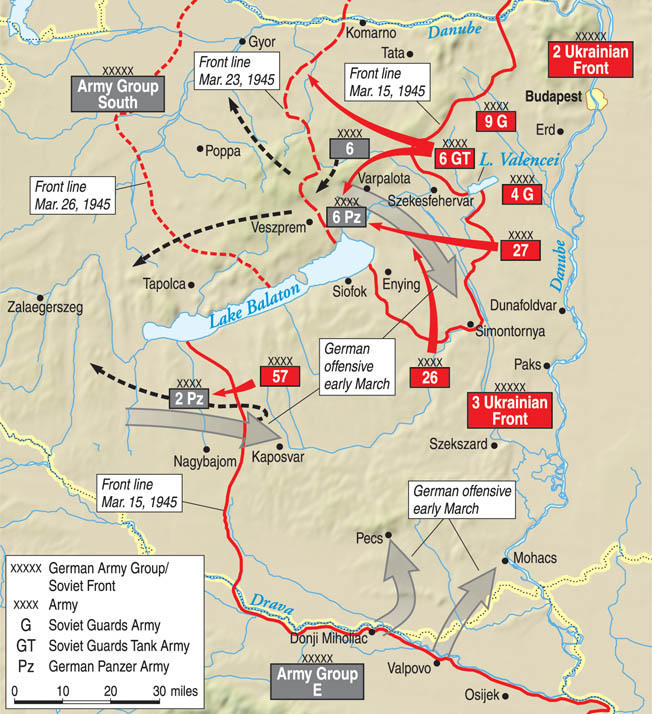

While Army Group South advanced south toward the Soviet forces between Lake Balaton and Lake Velencze to the east, other German armies would strike east against Tolbukhin’s left flank. Wohler’s attack would be supported by a secondary attack by Generaloberst Alexander Loehr’s Army Group E in Yugoslavia, as well as another minor attack by General Maximilian de Angelis’s Second Panzer Army.

By the start of Operation Spring Awakening, nearly 40 percent of the German Army’s heavy combat fighting vehicles in use on the Eastern Front were in Hungary. Under the strictest security measures, additional units made their way there. Col. Gen. Heinz Guderian, the German Army’s Inspector General of Armored Troops, disapproved of Hitler’s decision to send the Sixth Panzer Army into Hungary. Guderian believed its strength would be better employed behind the Oder River to slow the Red Army’s drive on Berlin. Hitler overruled Guderian, and the Hungarian offensive went forward as planned.

Hitler approved the final plan for Operation Spring Awakening on February 23. As part of the final preparations, he reinforced Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army with the I Cavalry Corps, comprising the 3rd and 4th Cavalry Divisions, and Generalleutnant Joseph von Radowitz’s 23rd Panzer Division. Radowitz’s troops would serve as a ready reserve to be committed at the most opportune time.

Dietrich assigned Preiss’s I SS Panzer Corps the center position, which stretched from Lake Balaton to a point west of Seregelyes. Bittrich’s II SS Panzer Corps took up a position on its left, and the I Cavalry Corps deployed on its right. Flank protection would be provided by the 44th Grenadier and 25th Hungarian Infantry Divisions. Dietrich’s first objective was to secure a crossing over the Sio Canal and capture the city of Dunafoldvar.

General Hermann Breith’s III Panzer Corps of Balck’s Sixth Army was to attack north of the Sixth Panzer Army from Seregelyes to Lake Valence. Its objective was to capture the area between Lake Valence and the Danube River. Two heavy tank battalions with King Tigers provided extra firepower for the III Panzer Corps and the Sixth Panzer Army. Generalleutnant Rudolf Freiherr von Waldenfels’ 6th Panzer Division would follow behind.

Guarding the left flank of the III Panzer Corps were the 3rd and 5th SS Panzer Divisions of SS- Obergruppenführer Herbert Otto Gille’s IV SS Panzer Corps. The IV SS Panzer Corps was badly depleted from the Konrad Offensives, but it would be sent into action anyway.

To the south, the Second Panzer Army held the front line south of Lake Balafon. By the time of the offensive, though, it could hardly be described as a panzer army. It consisted of four divisions equipped not with tanks, but with assault guns. Its best division was the 16th SS Panzer- grenadier Division. The Second Panzer Army’s objective was to capture Kaposvar. Army Group E was deployed south of the Second Panzer Army along the Drava River. Its objective was to establish a large bridgehead across the Drava near Donati Miholjac with its three divisions.

Although the Germans had employed strict security measures to disguise the transfer to Hungary, the Red Army knew a German offensive was brewing. As early as February 12, the Western Allies passed along intercepted communications regarding troop movements. Any doubt the Red Army commanders might have had was eliminated near the end of February when the last successful Waffen SS operation, known as Operation Southwind, went forward against the Soviet forces in Slovakia. In that offensive, the I SS Panzer Corps eliminated a Red Army bridgehead over the Gran River.

Tolbukhin’s 3rd Ukrainian Front would receive the brunt of the German attack. Created in October 1943, the units that constituted the front had participated in various Soviet offensives that had liberated Ukraine and Moldova from German occupation by August 1944. In the following months, the 3rd Ukrainian Front had invaded Romania, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia. Tolbukhin’s Red Army troops liberated Belgrade in October. Afterward, Stavka, the Soviet high command, shifted the front north to Hungary where it assisted Malinovsky’s 2nd Ukrainian Front in besieging Budapest and helped repulse German attempts to relieve the city.

While the Germans were clearing the Gran bridgehead, Stavka issued directives to Tolbukhin and Malinovsky to prepare for fresh offensives to capture Vienna and Bratislava, respectively. Soviet Premier Josef Stalin set March 15 as the start date for these offensives. Thus, Tolbukhin not only had to prepare for the upcoming offensive, but also establish a defensive plan for the forthcoming German attack.

Tolbukhin created a multilayered defense that stressed antitank obstacles and killing zones. Each layer had multiple fortified belts. The first two layers typically had two or more lines of trenches. Altogether, Tolbukhin had a defense in depth that stretched for 30 kilometers. But since the defenses were created in a short time, the soldiers only strung barbed wire in a few places and had not had time to construct concrete pillboxes.

The 3rd Ukrainian Front had approximately 406,000 soldiers and 407 tanks, assault guns, and tank destroyers. In addition, the Soviet 17th Air Army had 965 aircraft available to support the ground troops.

The 4th Guards Army held the 3rd Ukrainian Front’s right flank. The army comprised three rifle corps, each of which had three rifle divisions. The 4th Guards’ main task was to defend Szekesfehvar. Deployed on its right flank was the XXIII Tank Corps, which functioned as a mobile reserve.

To the left of the 4th Guards was Lt. Gen. Nikolai Gagan’s 26th Army, deployed directly in the path of the advancing Sixth Panzer Army. Gagan’s army was responsible for the area from Seregelyes to Lake Balaton. Because of the likelihood that it would be hit hard, the XXX Rifle Corps had half of the 3rd Ukrainian Front’s artillery and ample anti-tank guns.

The XVIII Tank Corps, another of Tolbuknin’s mobile reserves, was stationed in the Sarosd area where it could either assist the 4th Guards or the 26th Army as the situation developed. The I Guards Mechanized Corps also was deployed directly behind the 26th Army.

The 57th Army was deployed to the south of Gagan’s 26th Army. Comprising two rifle corps, its task was to guard a section of the front that stretched from the shores of Lake Balaton south to the Drava River. Although it had only six infantry divisions, each division had slightly more men than those in the other Soviet armies. It was deployed in the path of the Second Panzer Army. The V Guards Cavalry Corps was situated in the northeast area of the 57th Army in such a way that it might assist either the 57th Army or the 26th Army.

Stationed along the northern banks of the Drava River south of the 57th Army were the six infantry divisions that constituted the First Bulgarian Army. Although the Bulgarian divisions had a strength that was twice that of a Soviet division in numbers, its men had less combat experience. Stavka believed that a major enemy advance in the sector held by the Bulgarians was unlikely because of the difficulty the Germans would have striking across the Drava. Still, Tolbukhin was prepared to send elements of the 57th Army south to assist the Bulgarians if the need should arise. To the Bulgarians’ left was the XII Army Corps from the Third Yugoslavian Army, which was not part of Tolbuknin’s front.

Tolbukhin entrusted the 27th Army with his second line of defense. The 27th Army consisted of three Guards infantry corps, yet all of its divisions were significantly weaker in men and equipment than the 26th Army. The 27th Army held a section of the front from Lake Valence to the Danube River.

While it seemed as if the Red Army had an extraordinarily large number of troops in this sector, a typical Soviet unit was small in comparison to its German counterpart; for example, a Red Army tank corps in terms of men and equipment was equivalent to a German panzer division

Tolbukhin also had other units in his sector which, under orders from Stavka, he was forbidden to use. One of these units was the 9th Guards Army, which was slated for the drive on Vienna. Even if the 3rd Ukrainian Front’s situation grew critical, Tolbukhin knew from past experience that his request to use such units was likely to be rejected.

Overall, German intelligence had accurately estimated the number of Soviet armies, corps, and divisions against which the German forces would be attacking. But it failed to detect the guards mechanized and guards cavalry corps positioned in the assault route of the Sixth Panzer Army, failed to determine the location of two corps of the 27th Army, and failed to accurately assess the strength and disposition of the Soviets units.

Although the German intelligence omissions were important, they were nothing in comparison to other factors that would influence the Germans before and during the offensive. The security measures that the Germans employed in an effort to deceive the enemy, which in the end were futile, prevented orders from reaching anyone below corps level. This had a detrimental effect on final preparations for the offensive. In addition, some assembly positions were up to 20 kilometers from the actual starting points. To make matters worse, commanders were not allowed to conduct their own reconnaissance of enemy positions to their immediate front.

Dietrich and the staff of the Sixth Panzer Army had considerable concerns about the location chosen for the attack. In addition to being vulnerable to a Soviet thrust north of Szekesfehervar, several waterways and canals crossed the lanes of attack and threatened to slow the German advance. Moreover, only two of the roads were paved, and the dirt roads shown on the maps the Germans would be using were in reality no more than narrow paths.

Last but not least, the weather at that time of year was apt to hinder the movement of the tracked vehicles of the German panzer divisions. An early thaw in the spring of 1945 had turned the entire area into a morass. The region’s canals and drainage ditches had been unable to contain the runoff. During the first days of the offensive, the SS panzer divisions lost vehicles due to the saturated condition of the terrain. German tanks often sank in mud up to their turrets. The situation was particularly problematic for the King Tigers. Commanders of some units participating in the offensive requested a postponement of offensive operations until either the temperatures dropped low enough to freeze the mud or climbed high enough to dry the ground. Hitler and his advisers refused all such requests.

The effects of the bad weather delayed the II SS Panzer Corps to the extent that by March 5 some of its units still had not reached their starting points. Hitler was adamant that the attack begin on time, even if all participating units were not in place. The headquarters of Army Group South had experience with these conditions but still did little to assist with the requests. Rather than help those under his command, Balck echoed the orders coming from Berlin. Throughout the war he had always been overly optimistic about an operation’s potential outcome, and this operation proved no different than before. But Balck also had a tendency to blame others for shortcomings that ultimately were his responsibility. The situation was exacerbated by Balck’s disdain for SS officers due to previous experiences in the war. Specifically, Balck harbored a grudge against Bittrich for the failed relief of the Ukrainian city of Tarnopol in April 1944.

German corps commanders participating in Operation Spring Awakening distributed orders to their division commanders on the evening of March 5. With herculean efforts, most units had by that time slogged their way through the mud to their respective starting points. Hungarian liai- son officers had warned the Germans not to underestimate the mud season in their homeland, but their advice fell on deaf ears.

The II SS Panzer Corps, though, had not managed to reach its staging area. Bittrich made multiple pleas to have the offensive delayed until his divisions reached their starting points, but his superiors flatly rejected his repeated requests.

At 1 AM on March 6, Army Group E’s three divisions surged across the Drava in five places. Throughout the course of the day, the Germans consolidated their five small bridgeheads into two larger bridgeheads near Valpovo and Donati Miholjac. Not surprisingly, the Bulgarians were unable to repulse the Germans. Three hours later, the Second Panzer Army’s four divisions attacked eastward in a drive to encircle Nagybajom. Thirty minutes after that the 1st SS Panzer Division began a preplanned artillery barrage at 4:30 AM.

Other German units opened fire shortly afterward. Although the indirect fire did not have the results hoped for by the German commanders, German tanks and assault guns employed direct fire with good effect against the Soviet forces in the area. The I Cavalry Corps gained ground at the outset but was pushed back by the Russians.

Like the divisions of I Cavalry Corps, the 12th SS Panzer Division stalled after marginal advances, but it managed to hold onto its gains. The 1st SS Panzer Division made noteworthy progress when it exploited some weak spots in the Soviet defense; however, its gains were only two to four kilometers deep. As for the II SS Panzer Corps, its advance elements did not attack until evening and made negligible progress.

In concert with the Second Panzer Army, the Sixth Army established a bridgehead across the Hadas Ditch, which empties into Lake Valence. On either side of Seregelyes, the 1st Panzer Division and the 356th Infantry Division managed to advance only to the north end of the village by nightfall. The 3rd Panzer Division was unable to bring its full weight to bear as some of its units had not yet reached their jump-off positions.

By day’s end the attackers had advanced only three to four kilometers on a 3.5-kilometer front. It was fortunate for Tolbukhin that the damage was not more severe because III Panzer Corps had struck the seam between the 4th Guards and the 26th Armies. German air support was restricted on the first day due to inclement weather.

Tolbukhin and his staff had correctly predicted the German avenues of attack. The 3rd Ukrainian Front commander instituted measures designed to further strengthen the defense in the direct path of the German assault. He regrouped his artillery and shifted elements from the XVIII Tank Corps into the second defensive belt. In addition, the 27th Army’s XXXIII Rifle Corps was repositioned to block the I SS Panzer Corps, which had made significant progress on the first day of the operation given the weather conditions.

Rain mixed with light snow greeted the combatants at daybreak on March 7. The Germans renewed their attack across the entire front. Along the Drava River, Army Group E was unable to significantly enlarge its bridgeheads due to the mud. For the rest of the offensive, its divisions stayed on the defensive. Farther north around Nagybajom, the Second Panzer Army benefitted from captured enemy plans that detailed Soviet defenses. Based on the intelligence gleaned from the plans, the Second Panzer Army shifted the focus of its attack to its right wing.

A stubborn Soviet defense permitted little gain, and a stalemate ensued for the next few days. Between Lake Balaton and Lake Valence, the main attack pressed on as worsening terrain conditions trapped more German tracked vehicles, putting a strain on the already weakened infantry. Against the layered defense, the I Cavalry Corps made few gains. To its left the SS panzer divisions enjoyed some success. For example, the 1st SS Panzer captured Kaloz, and the 12th SS Panzer drove six kilometers into the Soviets lines. The II SS Panzer Corps, which was able to attack in force, also made significant headway, advancing six kilometers.

But the adjacent III Panzer Corps did not make any attempt to attack. Dietrich severely criticized its commanders for their lackluster performance. The IV SS Panzer Corps, though, did capture ground near Stuhlweissenburg that strengthened its defensive position.

An early morning frost on the third day of the offensive saw some road improvement. This was lost as temperatures rose, exacerbating the muddy conditions. The offensive finally looked like it might have a chance when the I SS Panzer Corps made the first real gains across a wide front when the 1st SS Panzer Division breached the enemy’s second defense line. Exploiting this momentum, the I Cavalry Corps also gained sig- nificant ground. The II SS Panzer Corps failed to follow up the gains of the previous day and became bogged down in heavy fighting near Sarosd. Orders were given for the 23rd Panzer Division to assemble behind the 44th Grenadier Division to be ready for a possible breakthrough. The 3rd Panzer Division was brought forward to attack Adony on the Danube River while the III Panzer Corps captured Seregelyes and an additional couple of kilometers.

These advances continued to be contested by the Soviets. Tolbukhin brought forward more of his reserves beginning on March 8, especially artillery and Katyusha rocket batteries. With the exception of XVIII Tank Corps, most of the Soviet mechanized forces had been held back. The following day major developments occurred between Lake Balaton and the Sarviz Canal.

The I Cavalry Corps made a surprisingly deep penetration with its 3rd Cavalry Division overcoming several defensive lines. These gains were assisted by the success of a night attack by the 1st SS Panzer Division. By the end of March 9, Dietrich had two corps through the Soviets’ primary defensive line. But the localized success had a drawback. The III Panzer Corps also enjoyed considerable success as its units advanced along the southern shore of Lake Valence before being stopped by Soviet forces at Gardony.

With his infantry suffering heavy attrition, Bittrich became deeply concerned over the losses suffered by his troops from combat and exposure to the elements. The 9th Panzer Division had lost more than a third of its strength by that point in the offensive.

Tolbukhin also became increasingly worried about the losses his units were incurring. The tempo of battle on March 9 compelled him to commit all of his reserves, except for a few small units. He informed Stavka that the situation was critical, and he asked if they would release to him the 9th Guards Army. His superiors flatly refused the request. They instructed him to make do with the forces at hand. As a result, Tolbukhin began to alter areas of responsibility along the front. He reduced the length of front for which the 26th Army was responsible. The result was that the 27th Army had to take up the slack. Its commander was startled to find that he was suddenly responsible for a critical portion of the front line. Tolbukhin also shifted units from the 4th Guards Army in the second echelon and placed them directly in the path of Dietrich’s advancing Sixth Panzer Army in an effort to slow the enemy’s momentum.

Frontline troops on both sides shivered in their positions on March 10 as the skies opened up and snow and freezing rain fell in western Hungary. This exacerbated the already poor road conditions. Nevertheless, the Second Panzer Army south of Lake Balaton experienced considerable success when the 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division exploited the seam between the Soviet 57th Army and the First Bulgarian Army. The panzergrenadiers advanced five kilometers, reaching the village of Kisbajom.

Meanwhile, the 25th Hungarian Infantry Division entered battle in the I Cavalry Corps’ sector. After a full day of savage house-to-house fighting, the understrength Hungarians captured the high ground around Enying. The 3rd Cavalry Division and the 1st SS Panzer Division reached the Sio Canal and secured sections of its bank in preparation for a crossing.

Elsewhere, the 12th SS Panzer, 2nd SS Panzer, and 44th Grenadier Divisions all made gains. In the Sixth Army’s sector, the 3rd Panzer Division surprised a pair of Soviet divisions by attacking amid a heavy falling snow. The panzer troops fought their way into the enemy’s second echelon of defense near Seregelyes. Its fellow division, the 1st Panzer, captured several villages. The pressure of battle compelled some of the German commanders to point fingers of blame at each other. Balck was accused of having misinformed Guderian about the status of the IV SS Panzer Corps. Balck reported that the corps had enough reserves to deal with a Russian counterattack when it no longer had such capability. As for Tolbukhin, he shifted units from relatively secure areas to critical ones to limit the enemy’s gains.

The weather improved on March 11, which enabled both Luftwaffe and Red Army ground attack aircraft to fly multiple sorties. With the support of their aircraft, Soviet troops were able to push back elements of the 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division around Kisbajom. The Second Panzer Army requested a change in the direction of its attack, but this was rejected by Wohler.

Instead, Wohler ordered the Second Panzer Army to renew its attack within the next 48 hours to keep Tolbukhin off balance and take the pressure off the Sixth Panzer Army. The Hungarians continued to advance along Lake Balaton, but they ground to a halt at Siofork. The German divisions that reached the Sio Canal spent the day securing its north bank and continued to search for crossing locations. While forward elements of the 12th SS Panzer Division were able to locate an intact bridge over the Sio, they were unable to exploit their discovery because it was blocked by burning vehicles.

The 23rd Panzer Division attacked Sar Egres, but it could not control the village. Despite the good weather of March 11, Dietrich sent a direct request to Hitler asking him to temporarily halt the offensive due to the rain and mud. Not surprisingly, Hitler rejected the request. Elements of the II SS Panzer Corps and the III Panzer Corps nevertheless managed to drive four kilometers into the Soviet 27th Army in some places.

The German armies involved in the offensive faced a determined, veteran commander. As Dietrich’s and Balck’s panzer divisions sought desperately to punch through the Soviet defenses, Tolbukhin masterfully shifted his resources in ways that prevented a decisive breakthrough. The Soviets’ defenses forced the Germans to make tactical adjustments. To catch the Red Army units by surprise, the Germans refrained from conducting preliminary artillery barrages before making an assault.

On the seventh day of the offensive, Army Group E ran out of steam. From that point forward its units did nothing more than hold their ground and fix the enemy units arrayed against them so that they could not be shifted to other sectors.

Tolbukhin, who already was deeply concerned over the condition of the 26th Army, watched in dismay as the German 4th Cavalry Division and 1st SS Panzer Division established bridgeheads across the Sio. These bridgeheads were approximately three kilometers deep and three kilometers wide. In addition, elements of the 1st SS Panzer Division entered Simontornya. On the opposite bank of the Sarviz Canal, most of the units of the II SS Panzer Corps could make no progress, although the redoubtable soldiers of the 44th Grenadier Division cleared the village of Aba. To the north, the three panzer divisions of the III Panzer Corps advanced two kilometers mainly because they benefited from the support of a heavy panzer battalion that used its King Tigers to blast Soviet positions. Despite the impressive gains made by the German forces that secured the Sio Canal bridgeheads, the soldiers of the 3rd Ukrainian Front had succeeded in preventing a breakthrough.

March 13 marked a week since the Germans launched what was to be their final offensive. The weather improved, and the roads began to dry out. Despite this, the Germans were unable to make any significant progress. There were two noteworthy exceptions. First, the 23rd Panzer Division captured Sar Egres. Second, the 1st SS Panzer Division occupied Simontornya. A change occurred in the nature of the fighting when the Soviet forces, which up to that point in the German offensive had only used self-propelled guns, introduced tanks to the battle.

The Soviets continued to hold their defensive lines, though Tolbukhin withdrew one division that had the potential to be encircled. The IV SS Panzer Corps reported increased enemy troop movement. If the enemy counterattacked, Dietrich believed his veterans would have sufficient time to establish strong defensive positions. German intelligence at the army and army group levels misinterpreted this activity in the 2nd Ukrainian Front as local reinforcement movement and not as preparation for a major offensive.

Stavka transferred Maj. Gen. A.G. Kravchenko’s crack 6th Guards Tank Army, which had approximately 500 tanks, and the 9th Guards Army from their positions near Budapest to the rear of the 4th Guards Army. The Germans did not detect the arrival of Kravchenko’s armored units.

On March 14, the German panzer forces were able to maneuver better than in previous days due to the arrival of better weather. But by that time, the panzer force divisions participating in the offensive had shrunk to 50 percent strength.

With the sun peeking out from behind the clouds, the 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division received orders to spearhead an attack that day, which only made limited progress in the face of heavy artillery fire from the Soviet 57th Army. Dietrich watched helplessly as his cavalry divisions lost all offensive capability. Although his panzer divisions were still able to make small gains against the enemy, it became increasingly apparent that there would be no armored break- through. Bittich’s II SS Panzer Corps held its ground in bitter fighting near Sarkeresztur. At that point Dietrich was greatly concerned about his flanks, which were vulnerable to enemy counterattack. Reports flooded into his headquarters about increased Soviet vehicle activity, particularly in the passes of the Vertes Mountains northwest of Lake Velencze.

Balck responded by frantically organizing every possible reserve unit to bolster the German and Hungarian forces in his sector of the battlefront. He reluctantly committed his last reserve, the 6th Panzer Division, to the battle. After making some initial headway, its attack was easily contained by the reinforced Soviet XVIII Tank Corps. Even the most optimistic of the German commanders realized by that time that the offensive had ground to a halt. Although they also were exhausted, the Russians sensed that they had won the battle. At that point, the armies of the 3rd Ukrainian Front began making preparations to resume offensive operations. Tolbukhin’s subordinate commanders ordered their units to move into the staging areas for the drive on Vienna.

The good weather held on March 15. The Second Panzer Army resumed its advance. To the north the Sixth Panzer Army and the III Panzer Corps of the Sixth Army tried to gain new ground on their respective fronts, but they had nothing appreciable to show for the blood spilled that day. The II SS Panzer Corps remained on the defensive. The only positive developments for the Germans were that the 1st SS Panzer Division slightly expanded its bridgehead and the 44th Grenadier Division erected a pair of pontoon bridges capable of handling tanks. Hitler and his advisers debated the merits of reorganizing their forces for a new direction of attack.

Unwilling to abandon his objectives, Hitler allowed the reorganization to proceed after an entire day was squandered in the debate. The upshot was that the lengthy delay put some of the units of the I SS Panzer Corps in greater danger from the looming Soviet assault than they would have been if they had received permission to adjust their positions.

March 16 dawned much like the previous 10 days. Heavy fighting occurred the length of the battlefront. Taking advantage of the good weather, the Soviet Air Force stepped up its operations flying numerous sorties against the Sixth Panzer Army and Sixth Army. On the southern end of the battlefront, the Russians attacked Army Group E’s bridgeheads. As for the Second Panzer Army, it only made negligible gains. Elsewhere, the I Cavalry Corps and II SS Panzer Corps remained on the defensive. The momentum had shifted by that point, and even the best plans for reorganization were nullified by the Red Army’s resumption of offensive operations. Both Ukrainian Fronts attacked in force on March 16. The 4th Guards Army and the 9th Guards Army, with the 6th Guards Tank Army and 46th Army following in reserve, struck the left flank of Balck’s Sixth Army northwest of Lake Velencze.

The Soviets targeted the Hungarian divisions, which were the weakest of the enemy’s units. In heavy fighting on the second day of the offensive, the Soviet 46th Army overran the 1st Hungarian Cavalry Division. Wohler responded by cancelling all offensive operations. The Germans had completely abandoned the Drava bridgeheads by March 20. The panzer troops fought tenaciously against the advancing Russians to protect a narrow escape corridor and avoid being surrounded and cut off. The fighting grew in intensity in the following days, and during that time the German retreat corridor narrowed to no more than two miles in width. Speed was of the essence, and the retreating German units abandoned their equipment and supplies as necessary to ensure their escape.

Some of the SS panzer divisions fell back without orders. Hitler threw a tantrum. He immediately dispatched a representative to Hungary to summarily strip the SS troops of their armbands, which had been bestowed upon them to signify that they were elite troops of the Third Reich.

As the Germans withdrew, low-flying Russian Ilyushin Il-2 Sturmovik ground attack planes pounded their columns from above and Russian tanks and tank destroyers pursued them on the ground. Dietrich’s and Balck’s panzer divisions fell back as quickly as possible given the conditions. Elements of Dietrich’s 6th SS Panzer Army fought for a short time on the outskirts of Vienna, but the weight of the Russian attack forced them to retreat to avoid being encircled. On April 2, the Soviet 57th Army and 1st Bulgarian Army captured the Nagykaniscza oilfields.

The Germans suffered 14,800 casualties compared to 33,000 Russian casualties. Malinovsky captured Bratislava on April 4, and Tolbukhin secured Vienna on April 13 after an 11-day battle.

In the final analysis, Hitler would have done well to heed Guderian’s advice to commit the Sixth Panzer Army to the defense of the Oder line to slow the Russian advance on Berlin. Georg Maier, deputy chief of staff for operations for the Sixth Panzer Army, offered a fitting summation of the failed offensive. “Time, pressure, poor weather, extremely difficult terrain conditions, [and] Hitler’s impatience joined forces with the well-prepared enemy defense to form a combined front,” he wrote.

In a way, it’s surprising the Germans had any success at all.