By Richard Statetzny with Ward Carr and Detlef Zer

BACKSTORY: Richard Statetzny was born on January 16, 1920, the youngest of five children, in Bieberswalde in the District of Osterode, East Prussia, Germany. According to the Treaty of Versailles, East Prussia was geographically separated from the Reich, but it was still German, and the former administrative structure remained.

Two of his sisters had earlier emigrated to the United States, one in the 1920s and the other in 1930, and both lived in Cleveland, Ohio. After Richard finished school, he did job training as a stage painter then volunteered for the Fallschirmjäger (paratroopers). However, he initially was not accepted because he was supposed to do his military service in East Prussia, and no paratroopers were trained there.

This is his story.

Because I could ride, I volunteered for the cavalry, but I was assigned to the mounted rifle platoon with the infantry regiment in Rastenburg. I did both my basic [riding] and advanced training there. After a half a year in Rastenburg, I was allowed to volunteer for the paratroopers because they were looking for recruits. I had another physical, was graded 1-A, and accepted. I entered the airborne school in Braunschweig in July 1940.

After four weeks there, we made our first jumps. They also trained us how to pack our parachutes. Then we reported to our regiment in the Lüneburger Heide [Luneburg Heath] about 40 kilometers south of Hamburg. Up until then, there had been only two parachute regiments in the Wehrmacht; ours was the third, the new one. My unit was 4th Company, 1st Battalion, 3rd Regiment, 7th Flieger (Airborne) Division.

After our training in Lüneburg, we moved to our garrison in the kaserne [barracks] in Wolfenbüttel near Braunschweig. It was then that the Wehrmacht marched through Yugoslavia and invaded Greece. [Editor’s note: During that time, Italy attempted to invade Greece, but the mountains, brutal winter weather, and stubborn Greek defenders stopped the Italians; Hitler came to the aide of Mussolini.]

So, we, too, were deployed. We boarded trains and traveled via Czechoslovakia and Hungary to Arat, Romania, where we detrained and boarded trucks. We went through Bulgaria and over the Thermopylae Pass through Greece and to the coast before reaching Athens.

We bivouacked in tents right on the coast and really had no idea what was going to happen next. But we could swim in the sea, and it was really relaxing. One evening we suddenly had to fall in, and our company commander addressed us. He said, “It was just announced––tomorrow we are taking off for Crete!” That was the first we had heard of Crete.

[To prevent the British Royal Air Force from knocking out German oil facilities at Ploesti, Romania, on April 25, 1941, Hitler ordered an all-out assault on British forces garrisoned on the Mediterranean island of Crete in an operation codenamed “Mercur” (Mercury). Richard’s 7th Flieger Division was a part of General Kurt Student’s XI Fliegerkorps. The first wave of paratroops dropped on Crete were carried by 493 Ju-52 transport aircraft.]

Right afterward, the planes were prepared for takeoff, and some of us were assigned to drive fuel to the more than 400 Ju-52s we had at different fields. That night we all checked our weapons one last time and put them in their cases.

Airborne Assault on Crete

Takeoff from Greece was scheduled for the crack of dawn [on May 20, 1941]. Just before we took off, we loaded our weapons and lifejackets on the plane. Actually, we were very well equipped to face everything but the blistering heat.

The planes could not take off quickly one after the other but had to wait for longer intervals than planned. This was because the planes created huge clouds of dust taking off, and this made it very difficult for the pilots to see.

We were in the first wave and were scheduled to jump over the road from Alikianou to Chania, near the Agya prison. We were still approaching the jump-off point when we came under heavy fire and suffered our first casualties.

Another thing was, back in those days, we couldn’t steer or control our parachutes because they only had suspensions, so the parachutes seesawed badly. Nowadays paratroopers can control their chutes, but back then we couldn’t.

I had no control at all over the landing and wound up on a roof, and a buddy landed on the roof of the next building. I hit hard and was pretty banged up. I jumped down on a parapet two meters below. Beneath that there was a horse hitched up to a cart full of oranges. Apparently the farmers had gotten up early to pick oranges that morning.

I jumped from the parapet, but instead of landing on the ground I wound up in the middle of the oranges. Right away the Greeks appeared with their hands raised and surrendered on the spot. Our unit encountered no other resistance.

The unit rallied and assembled at the prison. I brought the farmer’s horse, which I had managed to “organize,” and because I could ride the colonel immediately made me his messenger.

I was ordered to bring the message to a company to hold its position at all costs because the English were attacking heavily. On the way to the company command post, the English shot the horse right out from under me. Luckily I didn’t get a scratch, but the horse was badly wounded, so I had to shoot it. I managed to capture a second horse that was running around loose. I rode it, but it, too, was shot, so I had to continue on foot.

After I reported to the colonel, I was allowed to return to my unit. Then we got involved in heavy fighting with the English, who defended doggedly. Actually, the troops were New Zealanders and were well equipped. They even had tanks. We didn’t have any, so it was tough going.

At one point we had used up all our ammunition and had to get more from our ammo depot in the prison. The casualty station was there too, so we decided to check on two wounded buddies. In the cells we could see wounded English and German soldiers, often lying in the same cells together and being tended to by German medics.

The doctors had to do a lot of amputations. Because they did not have time, the medics had simply stacked amputated limbs on the stair landing right in front of the operating room. It was a shocking sight because blood was running down the stairs and it was hard to tell the original color of the doctors’ gowns due to the blood smeared on them.

One of our two buddies, the company commander, was dead already. Our first sergeant had a bullet lodged in his body but was soon evacuated to Germany. Completely depressed, we returned with the ammunition.

Finally, we managed to take the enemy position and secure it. The colonel ordered us to dig in and defend it at all costs. Before we could advance further, we had to wait for reinforcements. The airfield at Maleme was under heavy fire but was almost secured when an assault regiment of one of our mountain infantry units landed there.

A lot of them were shot as soon as they left the plane, but the others attacked immediately, and a short time later they secured the airfield. Then they moved to the mountains where they outflanked the English and forced them to give ground. Although the English troops were well trained and disciplined, they were forced to surrender in the end. They simply couldn’t resist any longer.

Afterward, we moved into Chania and took it. Two days later we had control of the whole island. Although the English were able to evacuate a large part of their troops, we still captured some 10,000 soldiers.

After the fighting was over, a provisional cemetery was made for the fallen comrades of our battalion. Because there were also English soldiers buried there, captured English officers and soldiers attended the ceremony. I saw the English and German officers shaking hands. Later the dead were reinterred in a large consolidated cemetery, which was organized by the Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge in Maleme on Crete.

[Editor’s note: The Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e. V. is a humanitarian organization charged by the government of the Federal Republic of Germany with recording, maintaining, and caring for the graves of German war casualties abroad––the German equivalent of the American Battle Monuments Commission and British Commonwealth War Graves Commission.]

On to Russia

We returned to Germany, where our battalion picked up replacements. In the Grafenwöhr Training Area, we trained them, and we went on maneuvers together.

One day in mid 1941, just after we had returned to the kaserne from training exercises, there was an alarm and we had to fall in at once. Our company commander announced the invasion of Russia and that we were to deploy immediately. We were to pack our equipment, board trains, and return to our garrison in Wolfenbüttel.

In the barracks there was a battery of heavy flak guns, and the fellows in the battery were ordered to belt the machine-gun ammunition for us and bring it to the train station. We boarded the train and went to Königsberg, East Prussia. The next day we flew to the front because the Russians were trying desperately to establish a bridgehead near Petroschino, and our units there were badly outnumbered and starting to give ground.

That night we landed at the Neva River and quietly approached the Russian lines where an allied French unit had taken up positions. It was one of the many volunteer units from France and the Netherlands that fought alongside us. This particular French unit was an artillery battery well known for being a top unit.

Their commander offered to support us with a sustained barrage before our attack.

Our commander replied, “I don’t want the artillery to fire because that would tip the Russians off. My troopers are used to fighting without artillery support because we don’t have any [in the table of organization and equipment]. We will just sneak up to the Russian positions and make a surprise attack.”

It was already cold out there at night. We had gotten so close to the Russians that we could hear the sentries talking and stamping their feet because of the cold. We were only about 30 meters from them, and they didn’t realize it.

Then we shot flares—green, white, green. That was our signal to attack. The whole front lit up, and then we broke through the Russian lines. They were so surprised that we rolled back their bridgehead within a half hour. The Russians suffered heavily because they could not leave their trenches.

At first we had almost no casualties because our attack was a complete surprise. But later on we suffered more and more losses as the Russians counterattacked five or six times that night and on into dawn. They were mostly drunk. They didn’t have anything to eat, but they did have vodka. Then they attacked. That was absolutely crazy. They didn’t all have weapons. And some had weapons that weren’t even loaded—they attacked with fixed bayonets. But Ivan couldn’t break through. We had MG 42s––the “Hitler Buzz Saw”—as well as other top weapons. Back then we were better armed than they were.

We were in Petroschino and Wyborgskaja a bit more than three months and were under heavy fire every day. The Russians fired their mortars continually, and we had a lot of KIAs. Many of the companies existed only on paper.

Return to Germany––and More Training

One day we were ordered to withdraw from the front line, and we were held in general reserve for some two weeks. Then we boarded trains in Puschkin (formerly Zarskoje Selo) and went back to Germany, where we were assigned to be a training battalion in Elsgrund, the troop training area in Döberitz. They had really nice barracks there. We tested and tried out new weapons, including a slightly heavier light artillery piece.

We also tried out the new steerable parachutes. When we first jumped back in 1940 we were equipped with the RZ 1 (Rücken-Zwangsauslösung 1). Now we tried the RZ 16, then the RZ 20. The RZ 16 had another type of harness, but it still had the simple suspension. When we jumped with that in the winter, we had quite a few injuries—broken bones and the like. Just part of being a paratrooper, I guess.

We trained our new replacements as well as troops from other units on heavy mortars and heavy machine guns. We also trained airborne combat engineers on them.

Whenever we came back from deployment, we got leave. And in 1941 we got Christmas leave. They even extended leave because we did so well on our last exercise.

In the winter of 1941-1942, we had an exercise at the Königsbrück Training Area near Dresden. We jumped against our infantry, who were playing the aggressors. Our mission was to keep a river ford open for our unit and to push back the “enemy” infantry.

There was snow on the ground, so we jumped with white parachutes for camouflage, and the infantry didn’t expect that. They had never seen anything like white parachutes before.

We flew over their positions at between 80 and 110 meters and jumped behind their lines. One guy crashed because his chute opened too late. And a weapons container crashed and was completely destroyed. But they didn’t halt the exercise.

Right after landing, we got under our white chutes which hid us and opened fire with blanks on the infantry unit. We did keep the river ford open for our unit, and we pushed back the “enemy” infantry, all with flying colors. It went so well that the commanding general sent us word during our Christmas leave that he had granted us four extra days of leave. Now that was a real Christmas present!

Afterward, we were at the Grossborn Training Area in Poland, where we trained Luftwaffe officers who were being mustered out of the branch. They were slated to be transferred to the infantry, and so they had to go through infantry officers’ training.

All of us paratrooper drill instructors were NCOs, and they were all officers. So to avoid any friction, and so that we wouldn’t hesitate to treat them like normal soldiers who needed a little guidance, they didn’t wear any insignia of rank. That really made things a lot simpler.

I remember one incident very clearly. We had an exercise for the officers to practice advancing underneath our supporting fire to get accustomed to it. So we covered the attacking officers with our machine-gun fire, and we were using live ammunition that day. The “cone of fire” of the heavy machine guns was normally at a range of around 3,000 meters, and it flew rather high before dropping.

In the exercise, “enemy” troops had advanced to about 800 meters from us, and the officers started to counterattack. We started firing over them while they advanced in scattered lines of skirmishers.

But, all of a sudden, they started jumping around and running away like rabbits. When they threw themselves to the ground, we saw that our salvoes were coming down right on top of them. Several of them were hit and fell down, but luckily they came away with only bruises.

An immediate cease-fire was ordered; the machine gunners were arrested and taken to the guardhouse. An investigation started right away to determine the cause. At first we thought that the gunners had changed the barrels too late and the machine guns were inaccurate because the rifling in the barrels had been worn out.

Later, however, our armorers determined the real reason. The Luftwaffe officers had to provide the ammunition for this exercise, and they had older ammunition from Czech armaments factories. Czech ammunition was much harder than the ammunition we normally used then, and that made our machine-gun barrels wear and burn out quickly.

The Czechs had good weapons. In Russia we preferred to use them instead of ours because Czech weapons didn’t rust so easily. Often our weapons got corrosion pits in the barrels, but if you pulled the ramrod through the barrel of a Czech weapon once, it was clean again.

To North Africa and El Alamein

In July 1942, we entrained and went to Greece, then flew in Ju-52s to Crete, where we stayed a day before flying on to Tobruk.

I don’t remember how long the flight to Tobruk was, but I do remember that we landed there in a sand storm. That was terrible. From there we had to hitch rides to the front because there was no transportation heading toward El Alamein. So we all lined up along the Via Balbia, which led to the front. We also stopped all the vehicles that were heading our way and asked them to take as many of us as they could. So it took a bit more than three days until we all arrived at El Dab’a, where we assembled and bivouacked by the sea.

We then marched to the front where we took up a position far to the south of the Qattara Depression. Its deepest point is below sea level, so the heat was scorching. It was a stone desert, so we couldn’t dig trenches; we had to make barricades out of stones. It was pretty exhausting, and we didn’t get any clean water. The water I did drink, I couldn’t keep down—I vomited it out again. It is a wonder that nobody got seriously ill.

But our cooks kept us fed. The field kitchens were located in a wadi [a dry stream bed] two or three kilometers behind the front. They cooked the meals there, and at night, usually around 11 pm or midnight, they brought the rations to the front and we ate then. They could only do this in the dark because the whole area was open terrain and was patrolled by English airplanes.

Then the nights weren’t cold yet. When winter began, it really got cold at night, and the days were also wet and cold. [Richard doesn’t say much about El Alamein, but his unit was not involved.]

After the Battle of El Alamein, we also had to withdraw. We had held our lines, and the English couldn’t get through. But they were able to break through in force near the coast. So we were ordered to disengage and withdraw to avoid capture. Despite this, a large number of our troops were captured. We were then ordered to withdraw so as not to be bypassed and surrounded; we retreated on foot. However, we did have a few vehicles for our antitank weapons, and they kept the English attacks at bay.

We were on the move with General [Hermann-Bernhard] Ramcke, and one morning [November 6/7, 1942, according to accounts] our rear guard reported that a large convoy of English vehicles had encamped and was being guarded by tanks very near us.

So General Ramcke ordered us to advance in small groups and see if we could capture the vehicles in the column without firing and drive them away at once. Believe it or not, we did it! We captured all the vehicles, along with the English drivers who were at the wheels and replaced some of them with our drivers. We started to move without the tanks noticing.

By the time they realized what was going on and started to chase us, it was too late. We zigzagged through the stone desert and obliterated our tracks so they couldn’t follow us. Our mixed English-Afrika Korps convoy got tangled up with an English convoy. But they didn’t notice that our column had different drivers, either. We managed to break though and reach our rear guard, which was right next to Rommel.

I saw Field Marshal Erwin Rommel several times in Africa, the first time in Marsa El Brega, behind Bengazi. We made our backup line there to stop the English advance. We were supposed to be the rear guard and were ordered to delay the English as long as possible to allow our troops to withdraw and form a new line of defense. Then we were to retreat past those lines; we were supposed to leapfrog rearward. We were too weak to stop the English completely, but leapfrogging would gain time for us.

In Marsa El Brega, Rommel flew in on a Fieseler Storch to check out our positions and to see how well—and how long—we could defend the position. Our battalion commander [Baron Friedrich August Freiherr von der Heydte] was there too. Rommel went straight to our positions, and each unit commander—me included—had to give him a report. That was the first time I saw Rommel personally, and I saw him two more times at the front.

Then we leapfrogged back to Tobruk and Benghazi. We continued retreating back to Tunisia, where we first occupied the old positions that the French had built. We were always deployed at the hot spots. Finally, we were in Hamam-Lif, a city right near Tunis. That was the end of our retreat.

The English attacked Hamam-Lif. They must have had 150 tanks, more tanks than we had heavy weapons. I was in position with my troops at the edge of the city. I ordered the NCO mortar crew chief to fire, then he said that all the ammo had been expended. So I told him to spike the mortar so the English wouldn’t get it and then to lead his men back to the battalion combat command post in the city.

As the highest ranking person remaining, I was now in command. When I reached the abandoned mortar emplacement, I also tried to reach the battalion combat command post. So I took off, and just before I got there I was running between houses and suddenly landed directly in front of an English tank. The officer in the turret looked at me and said in good German, “Go on in this direction and you will come upon English troops.” And—I will never forget this—“you will get a good meal and lots to drink.”

They didn’t disarm me, so they didn’t notice that I still had my pistol. Then they sent me on, but I wasn’t planning to go into captivity and become a POW. All at once I dashed into a house, ran to the other side, jumped out the window, and headed toward Grombalia, where I figured our troops were.

A bit later I came across some of our infantry grunts from another unit and went along with them. We were fired at and even shelled by artillery, but luckily no one was hit. We ran inland and into a wadi, but we lost track of each other later on. I had to climb over a mountain ridge.

Later that night I was hungry and really thirsty and came across an Arab tent. I went to the people in the tent and tried to explain that I only wanted some water. I tried speaking German mixed with a few words I knew in other languages. Suddenly, a well-dressed Arab appeared and said in fluent German: “You will get everything you need. Wait just a minute.” Then I got something to eat and drink. I asked him where he learned such good German, and he told me that he had studied in Germany.

Then I asked if he knew if there were still German troops around, and he said, “Yes, there are German troops near Grombalia, but you can’t get through. There are American troops blocking the way. If you want, I can lead you through their lines.”

So he led me though a mountainous area between two strongpoints and to a cave beyond them. When we were in the cave he showed me our exact location on one of the maps that I always carried as the leader of the HQ Company personnel.

I didn’t even need my prismatic compass to determine the route I had to take; he showed me that, too. “You have to go over the mountain ridge and you will most likely meet German troops.” I thanked him for his hospitality and help; then we parted.

I was on the move the whole night and kept climbing the whole time. At dawn I saw several fires. I didn’t believe there could still be German troops there, so I snuck up carefully. When I got up close, I heard a voice speaking in the Bavarian dialect. It was a master sergeant in an armored unit in the advanced covering position. Although I am from Prussia and had a completely different accent, hearing Bavarian made me feel right back home again. So I approached and identified myself.

After they fed me and gave me something to drink, I continued on my way and encountered paratroopers from Lt. Col. Walter Koch’s unit. [Koch was a Knight’s Cross recipent from his actions during the airborne assault of the Belgian fort of Eben-Emael in 1940]. His unit was not part of General Ramcke’s command but had been sent to help keep the English and American forces at bay. In the ensuing actions we fought alongside them both on their left flank and their right flank.

[In October 1942, Adolf Hitler issued his infamous “Commando Order,” which directed German soldiers to summarily execute any captured Allied commando troops. Koch publicly denounced the order and refused to carry it out. While in North Africa, Koch stopped another German officer from executing British POWs. Perhaps as a result, while on convalescent leave back in Germany after having suffered a head injury, Koch died in a “mysterious” car crash in October 1943. Some believe his death was authorized by Hitler for refusing his order to kill captured commandos.]

Of course, I reported immediately to the company commander of this section because I did not want to risk being arrested as a deserter. The first thing I did after that was go right to sleep. Later, a grunt woke me and told me to report to the company commander again, who told me that the game was up here.

He distributed everything the company and battalion had in the way of money or cigarettes to his troops. He told us, “If you are captured, maybe this will help you if you want to try to escape. You can bribe the English or the Arabs so they will give you a hand.” That was good.

Then a soldier arrived and said that vehicles from Brigade Ramcke had managed to get through and had just arrived and were heading toward Cap-Bon. The company commander said: “If you want, you can ride with me. I am going to the Luftwaffe Command, Africa. We want to see if we can get on a plane heading for Italy.” I took him up on the offer and went with them.

The command was located quite a way from Cap-Bon. When we arrived there, we actually saw our brigade staff vehicles and even the commander’s car. General Ramcke had already returned to Germany, but the driver took the car and was there with the remaining staff, all of whom I knew personally. They had come to see if they, too, could get on a plane heading out. So I joined them; there were maybe eight or 10 of us altogether.

The Luftwaffe Command even gave our battalion chief of staff a certificate stating that we were “essential training staff for paratroops and airborne units,” which allowed us to fly with the next departing plane. We took the certificate and drove to Cap-Bon, but the airfield had been badly bombed and strafed, and planes could no longer land there. We stayed at the field until we heard the radio announcement that the Afrika Korps had capitulated. So we knew the jig was up and that we were stuck there.

We put all the military equipment in the commander’s car, doused it with gasoline, ignited it, and blew it all up. We didn’t have anything left except for the rations we carried. It was May 13, 1943, when we became prisoners of war.

Prisoner a Second Time

Shortly afterward, English vehicles and an armored recon car with an officer arrived. We formed up, ready to surrender. Then our chief of staff gave a short talk and told us we only had to give our name, rank, and home town while in captivity. He said we should take leave of home and think about our families.

The English surrounded us, and an officer approached. He knew that we were the last remaining paratroop unit in Africa. He promised us that we would be treated fairly and that English vehicles would transport us to the POW camp. This combat unit treated us well; they even gave us tea. I have to say, they treated us fairly.

The officer stayed there for a few minutes. Then vehicles came and took us to the camp; it was there that things got bad. The English didn’t have much to eat and drink themselves, so we almost died of hunger and thirst. Later, the Moroccans took us by train to Constantine, Algeria. They were English allies in French military service.

When the train stopped at a station on the way, we paid the Moroccans to fill our canteens. They simply took our money and threw the canteens away. In Constantine things were not any better.

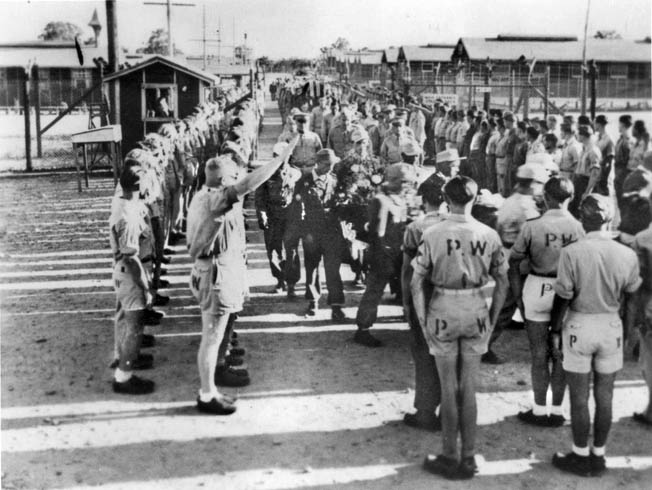

On June 7, 1943, we were brought to Schanzi in Tunisia and handed over to the Americans. The stockade was well-equipped. An American stood on a box and gave us a talk in perfect German—an American speaking perfect German!

I will never forget what he said: “Comrades, throw everything away that you still have. You will get everything you need new, and it will be better. You will even get as much as you want to eat and drink—or my name isn’t Mayer and I’m not from Dortmund.”

His parents had emigrated to the United States, so he became a soldier there. And he was as good as his word. We got new canteens and were fed so well that we couldn’t keep the food down because we weren’t used to eating so much. We all had the trots; that was really bad. But the American food really brought us around and pepped us up.

On July 13 they took us from Schanzi to St. Barbe de Djaladat. Two days later we started a long march to Oran, where we boarded the English ship HM Reina Del Pacifico and headed to Glasgow, Scotland.

On board, a buddy found a water faucet that we could drink from on the sly. We didn’t think we would be allowed to drink as much as we wanted, so we all agreed that we would only take a few swallows at first. Then, when the water supply held up, everybody drank his fill. Then all of us could fill our canteens. We were lucky—the water kept flowing until we reached Scotland.

On July 25, 1943, we disembarked and were transported by train to Oldham in England. In the camp, they immediately took away our canteens and locked them up, which caused a huge protest. After our experiences in the desert, we felt like we were being sentenced to death without our canteens.

A couple of days later we found out we were being shipped to America, and some of our group broke into the cellar the night before we were to leave and took a number of our canteens. They were able to overpower the English guards, who were somewhat elderly, and lock them in the cellar. (I didn’t hear about this until we were at sea.) The next day, August 2, 1943, we entrained and went to Liverpool, where we sailed to America on the James Parker.

On August 12, 1943, we arrived in New York, where we first went to a delousing station. We didn’t have lice, but we had to go through the procedure. Then we went ashore where they recorded our personal data again. Right after that we were loaded onto trains.

The trip was pleasant. The cars were Pullmans, and there were six seats in each compartment, but only four of us per compartment. We could fold down the seats to make beds at night, so we all had enough room.

We rode for what seemed like a long time through the country, and on August 16 we arrived in Roswell, New Mexico, where there were already German POWs. The camp officials asked us if we had any relatives in the United States whom we would like to contact. I gave them my two sisters’ names and their city of residence, Cleveland. But I didn’t know their street addresses. The camp officials got their complete addresses, and we started writing.

The Roswell German camp commander, a sergeant major in the paratroops, read us our Geneva Convention rights. One provision was that officers and NCOs did not have to work unless they wished. Those of us who chose not to work were sent by train to a special camp—the base camp in Brady, Texas, where our daily activities included sports and academic lessons organized by the POWs themselves. I started training as a forest ranger there.

One day in Brady, the camp authorities picked me up and took me to the American camp commander. A big package for me from one of my sisters had arrived, and I had to open and unpack it in the presence of the commander. It was like Christmas: several cartons of cigarettes—although I didn’t smoke—plus cookies, cakes, chocolate, and other candy. Best of all, I was allowed to take everything back to the barracks with me.

With all my buddies watching intently, I unpacked it again, and we divided everything up. My mouth was full, and I was still munching away when I was ordered to report to the commander again and pick up another package from my other sister.

While I was in Brady, I got several surprise packages like this—especially for Christmas. I had written my sisters and asked them to send me gym shorts, and I sent my measurements, waist, etc. But I forgot to mention the units of measure. So when the package came and I tried the pants on, the fellows were rolling with laughter. You guessed it—my sisters had simply used inches instead of centimeters. The pants were big enough for two or even three men!

In the letter that came in the package, my sisters explained how difficult it was to get pants that size. They couldn’t imagine that their “little” brother could be an athletic paratroop with a figure like that. Later, the camp tailor made me two pairs of pants out of it!

On May 25, 1944, trucks took us to Bowie, Texas, where we stayed until we left for Tonkawa, Oklahoma, on August 9 and arrived there two days later. We stayed in Tonkawa around nine months, and I continued my forestry training course there.

On June 1, 1945, we left for Florence, Arizona, via El Paso, Texas, and Casa Grande, Arizona. We stayed in Florence for about three weeks, and then, in July 1945, after the war in Europe was over, we went to Stockton, California.

A New Sport—American Football

When we arrived at the stockade, the other POWs were just coming back from their work details. When they saw us, they jeered and said, “Hey! Did we win the war after all?” because we were wearing our old uniforms, now freshly laundered, complete with rank and insignia.

At first we were assigned to clearing woodland and vegetation. Since Stockton was the biggest logistics and ordnance harbor for the Pacific Theater, most of us POWs were employed in various handling and trans-shipment stations.

One day they announced that all those interested in American football could join the team. Since I was sports-mad, I was all for it. They showed us a film and introduced the game to us. Then they wrote down all of our names and work stations. At the time, I was employed in the paint shop painting signs.

The very next day they picked up all the football players from their work stations and took us to the stockade, where our future coach, Sergeant J.P. Polczynski, greeted us. Then we enjoyed a hearty meal because “football players have to be full of energy and ready to go!” That was the procedure every day from then on—first a good meal, then practice. We each got a complete set of equipment.

At first only the players on the first string got a full set of equipment, including football shoes. All of the equipment was donated by American football teams; the second string had to make do as best they could.

The football shoes were made of very soft leather and provided our feet good, solid support. The quality was outstanding. I really took care of them. (After the war, I even took them back home with me. When I first got back to Germany, I lived with my sister in Dortmund-Lindenhorst and played in the local soccer club there. Nobody else had such top-quality shoes back then.)

Our three coaches explained the equipment to us. We had items in all sizes there, and everyone found the right fit. Nowadays all football players wear helmets with facemasks, but only Willi Scheuerer, from Heidelberg, one of our first-string players, got a facemask then.

At first the equipment was strange for us, but we didn’t worry about it. The equipment was part of the game we wanted to be successful at. We practiced in equipment from the very beginning, and none of us had any problems with it.

We had enough players for two complete teams, so the coaches could substitute during the game. We called ourselves Kiernan’s Krushers, after our backfield coach, Captain James M. Kiernan, Jr. Our head coach was Sergeant J.P. Polczynski, and the line coach was Lieutenant W.E. Brewer.

I played in the backfield on offense and carried the ball. There were three of us lined up in a row, and we exchanged the ball so that the defense couldn’t see it. After about a month of practice, we were ready to play the team from the other stockade, “Barager’s Bears.”

The “Barbwire Bowl Classic” was on Sunday, January 13, 1946—and it was the first American football game played by POWs in the USA. Therefore, it got lots of exposure in the local press. Big grandstands were erected for the spectators, who included the military brass and high-level officials with their wives. And, of course, all of our buddies from the stockade were there.

Before the football game, two teams of fellow POWs played a soccer game, our camp against theirs. And when the two football teams came out, the American spectators cheered us really loudly and enthusiastically, and during the game the American spectators cheered us on again and again. They even cheered us on by name, which they got when our coaches yelled instructions to us. Our fellow POW spectators, however, were a bit quieter because they didn’t really understand the rules of the game.

We won, 6-0. Unfortunately, I have forgotten who scored our touchdown and what kind of play it was.

Right after the game, both teams took a shower, then we put our military uniforms back on and went to the Officers’ Club, where each player was introduced individually by name and position to the assembled guests.

We sat down at a long table and were served a feast, which was so ample that we had enough left over to take our buddies in the stockade. As a memento, each player got a big team picture.

(Everywhere I went afterward, that photo was a real help. Whenever we were transferred to another camp, they searched our duffel bags. And I kept the team picture on top. It was like magic. As soon as the guards saw that, they stopped searching the bag and waved me on.)

Unfortunately, Barager’s Bears won the rematch, 20-0, two weeks later. It was played in the other stockade (The Fairground). Because I can’t remember too much about it, I suppose that it was not such a big event as our first game. I think that besides us, only our soccer team was there from our stockade and that they played a game against the Fairground team before our football game. But the POWs from the Fairground stockade were there as spectators.

After that, we did not have any more practices or games because they did not offer football anymore.

I remember one day, just as I was going out to play some soccer, they told me I had a visitor. It was my sister Gertrud, who had arrived from Cleveland after three long days on the train! We met at the gate in front of the guards’ quarters. It was a very emotional moment because it was the first time we had seen each other in 15 years.

In one of the barracks we saw Captain Kiernan who was on duty as Officer of the Day. A sergeant examined the gifts that Gertrud had brought me and did not want to hand out some of the items—underwear and a sweater. I protested and asked the sergeant to see what Captain Kiernan had to say. The sergeant came back and told me I could keep all the gifts.

For lunch I had to go back to the stockade. Captain Kiernan ordered the jeep to take my sister to Stockton for lunch and bring her back. Then we were allowed to spend the whole afternoon together. It was thanks to football that my sister and I had so much time together because normally visits were only one hour.

Back Home in Germany

I left Stockton at the end of February 1946, and—with stops in Benicia, California, and Rupert, Idaho—arrived at Camp Shanks, New York, in July 1946. On July 22 we boarded the Texarkana, the last ship to leave the camp, and arrived in Le Havre, France, on August 1. We passed through Camp Bolbec to Attichy, where we entrained for Frankfurt on August 13. From there we went to Munsterlager by way of Babenhausen. Finally, during the first week of September 1946, after more than 61/2 years in uniform, I was released.

I went to Dortmund, where I had relatives I could live with because I couldn’t go back to East Prussia. All of the family in Germany got regular CARE packages from my sisters in the United States, and this was really a great help.

There is a strong bond between paratroopers—even former enemies. After the war I joined the Bund Deutscher Fallschirmjäger—the Association of German Paratroopers, which was not politically oriented—where I got a chance to meet up with former buddies who had survived the war. A permanent feature of these meetings was a ceremony to honor the fallen paratroopers.

Later on, the wives attended, too. The meetings became more social occasions, at which people also talked about private matters such as family, work, and the like. Naturally, new friendships developed. Several people took group vacations on Crete and established contacts and friendships with the locals. They also visited military cemeteries on the island. The supervisor of the cemetery at Maleme was a former Crete partisan. When his wife got seriously ill, we raised money so she could go to Germany for treatment.

I was also made an honorary member of the New Zealand Crete Veterans Association; the New Zealanders got in touch with the Bund Deutscher Fallschirmjäger after the war and asked us to join.

Naturally I am proud to have been a paratrooper. We were elite troops, and during the war we were accepted and recognized by the citizens. We were welcomed everywhere we went in Germany. Often, when we went into a restaurant and people saw we were paratroopers, they didn’t let us pay the bill—they paid for us. We had a good reputation.

I am also proud of my comrades. During combat we could depend on each other 110 percent. I kept in contact with my paratrooper comrades by phone or mail until they died. The last other one died in 2015, so I am probably the last.

Postscript: After the war, Richard worked as a master painter, decorator, and varnisher in the company Johannes Rathgens GmbH & Co. KG, in Dortmund until his retirement. Today Richard is 96, in good health, and living in Dortmund. (Thanks to Detlef Zier, Richard’s son-in-law, for his invaluable help with this article.)

A nice essay. Thanks.

I lived in Tonkawa, Oklahoma when I was a young child in 1947-1948. I remember the abandoned POW encampment, as it was next to the cemetery where I have relatives buried.