By R.J. Seese

While making business calls in Tampa, Florida, during the summer of 1980, I spotted a strange looking tracked contraption atop an overgrown pedestal in front of the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve Center. Business was temporarily forgotten as I inspected and photographed the deteriorating remains of what was clearly a machine originally built with precision and purpose.

I learned it was the third prototype of a hurricane rescue vehicle designed and built by Clearwater, Florida, resident Donald Roebling and that it had been on display in that location since being donated by the builder’s widow in 1965. Further, after being modified to military specifications as an amphibious ship-to-shore tracked vehicle the Marines called an amtrak, it spearheaded the amphibious landings on numerous Japanese-held islands in the Pacific during World War II.

The amtrac became such an important component of American amphibious tactics in the Pacific that Vice Admiral E.L. Cochrane, chief of the U.S. Navy Bureau of Ships during World War II, noted, “There is not the slightest shadow of a doubt that the overwhelming victories of our forces at Tarawa, Kwajalein, Saipan, Tinian, Guam, Palau, and Iwo Jima would not have been possible without the amtraks.”

Millionaire philanthropist Donald Roebling made these victories possible. He was the great grandson of John Augustus Roebling, who invented “iron rope” and incorporated it into his design of the Brooklyn Bridge, and grandson of Washington Augustus Roebling, who supervised construction of the bridge. As millions of Americans struggled through the dark Depression years Donald, heir to the Roebling fortune, led a life of luxury on his seven-acre estate in Clearwater, Florida.

Born in New York City on November 15, 1909, Donald Roebling’s stature was as excessive as his life. He fueled his well over six feet and 350-pound frame with rich foods and chocolates. His girth tended to overpower his handsome features, and he suffered from diabetes and related health issues. Seeing therapeutic qualities in the warm Florida climate, he chose the little community of Clearwater as the place to build a palatial home for himself and his new bride.

Donald was educated as an electrical engineer but instinctively understood and loved mechanical engineering principals. Much of his time was spent tinkering in his machine shop, but he was also extremely interested in radio technology and the study and collection of postage stamps.

The Need for a Rescue Vehicle

The story of the amtrac begins with the catastrophic South Florida hurricane that smashed ashore at Miami on September 18, 1926, with winds in excess of 150 miles per hour. As the storm left Miami and tore across huge Lake Okeechobee, it created a storm surge that breached the lake’s dikes, flooding several hundred square miles of land. The death toll from the storm was estimated at 2,000. Many in the flooded areas perished because they could not be rescued from higher ground or buildings and trees.

For Donald’s father, financier John Augustus Roebling II, the hurricane was a personal tragedy. He had a winter home near Lake Okeechobee and was well acquainted with South Florida. As John Roebling reflected on the fact so many deaths had been caused by the inability to rescue people from areas made inaccessible by floodwaters, he concluded there was a humanitarian need, and perhaps even financial potential, for a rescue vehicle that could traverse both land and water.

When a less devastating but still destructive and life taking hurricane struck South Florida in 1933, he decided it was time to act. John Roebling chose a Machiavellian approach; he would harness the mechanical creativity of his nonconformist and to that point relatively unproductive son to build a rescue machine.

Donald Roebling’s Designs

Donald seized the challenge with gusto and with the dedicated assistance of associates Earl Debolt, Warren Cottrell, and S.A. “Al” Williams, set about designing and building the first version of an amphibious rescue tractor.

Donald Roebling concluded there were two primary challenges to overcome. The first was to create a vehicle light enough to maintain buoyancy without sacrificing the strength needed for overland travel through difficult terrain. The second was to design a single propulsion system for both land and water. Roebling’s answer to the first was to use a relatively new lightweight material called Duralumin. His answer to the second was an ingenious system of bogie and idler wheel-driven tracks for land with T-shaped cleats attached for movement in water.

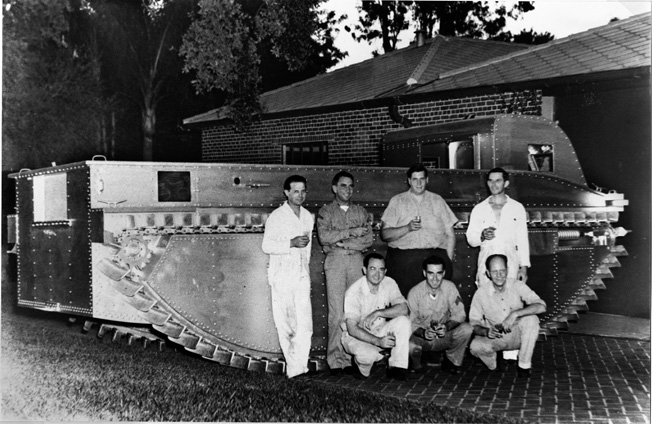

While the forming of the large Duralumin structural parts was sublet to the Bushnell-Lyons Iron Works in Tampa, the machining of most other parts and all final assembly was accomplished in Roebling’s machine shop and garage. Testing of the machine at various points throughout the development involved clinking around the mansion’s brick driveways and plunging into its huge swimming pool. Following two years of design and construction work, a first model of what Roebling had decided to call “The Alligator” was deemed ready for field testing.

This first machine looked like a huge shoebox. It was 24 feet long, nine feet, 10 inches wide, and weighed 14,350 pounds. Power was provided by a 92-horsepower, six-cylinder “flat head” Chrysler marine engine. Crawling over the mangrove swamps and open plains that surrounded Clearwater in the 1930s, the land speed of 25 miles per hour was deemed satisfactory.

Donald and his team knew they could do better and set about more versions of the machine. Completed in early 1937, their third design was four feet shorter and almost 8,000 pounds lighter. The width remained nine feet, 10 inches. Roebling would later explain that while the length was based on reasonably solid engineering principles the width was based on the fact that the doors to his garage were only 10 feet wide.

“Roebling’s Alligator for Florida Rescue”

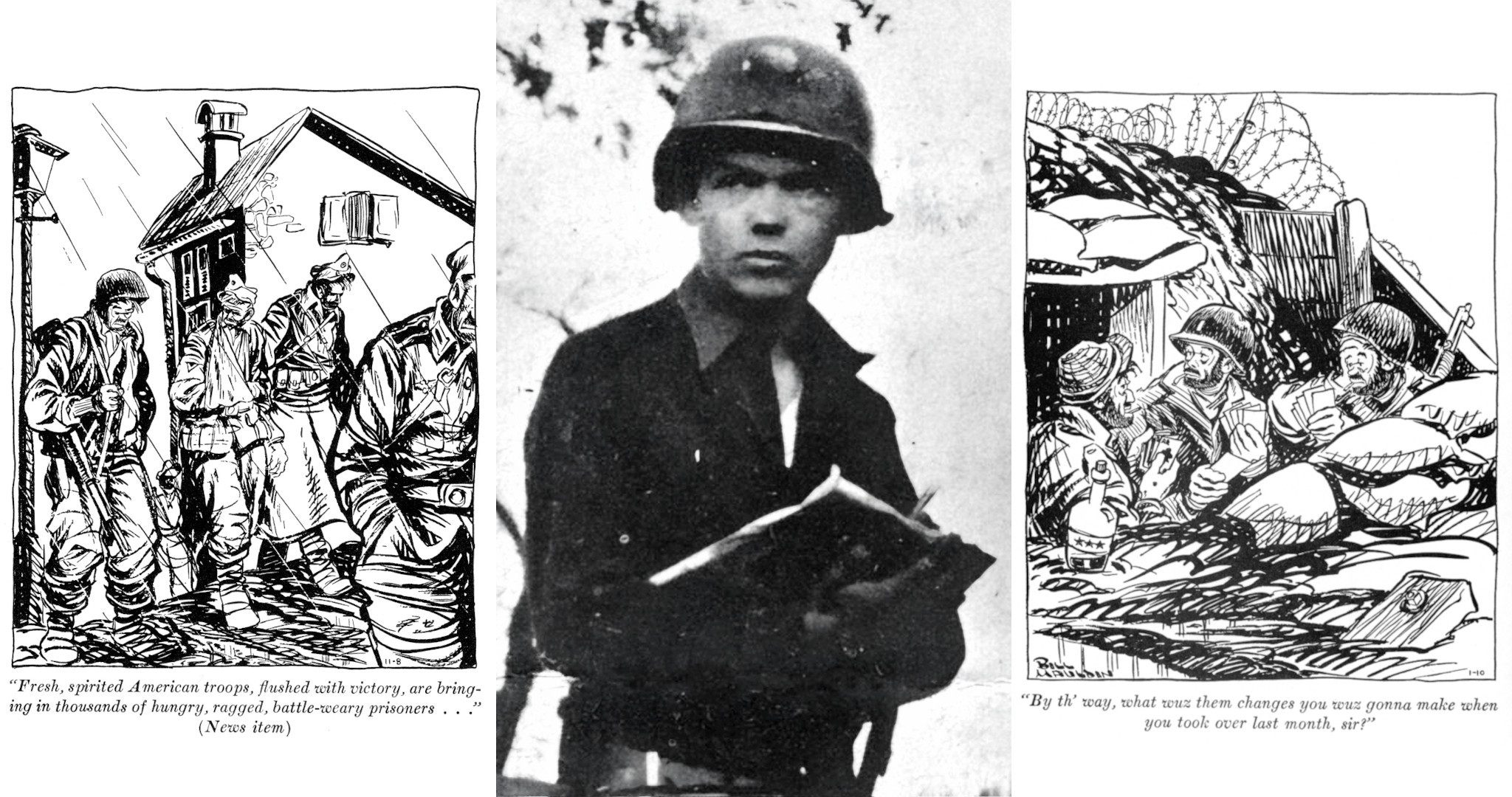

In mid-1937, Life sent a team to Clearwater. The resulting pictorial article in the October 4 issue was titled “Roebling’s Alligator for Florida Rescue.” It is fortuitous for America that the article was read by Fleet Battleship Force Commander Rear Admiral Edward C. Kalbfus. With the thought that Roebling’s invention might hold military promise, Kalbfus brought it to the attention of Fleet Marine Commander Major General Louis McCarty Little, who sent a copy to Commandant of the Marine Corps Major General Thomas Holcomb.

Japanese imperial expansion had made possible war in the Pacific a primary focus of Navy planning. Amphibious assaults were a key element of such planning, and there was at that time no adequate transport for the mission of landing troops on Japanese-held islands. General Holcomb recognized the potential of Roebling’s amphibious machine and directed Brig. Gen. Frederick Bradman, president of the Marine Equipment Board at Quantico, to evaluate the Roebling vehicle and make recommendations. Bradman assigned Major John A. Kaluf to investigate the military potential of the Alligator.

Adapting the Alligator for Military Purposes

Kaluf observed and took 16mm movies of the Alligator performing on land and water and even personally operated the Alligator in both environments. His enthusiastic recommendation to the Marine Equipment Board was that Roebling’s machine was precisely what was needed to transition fighting troops from sea to land.

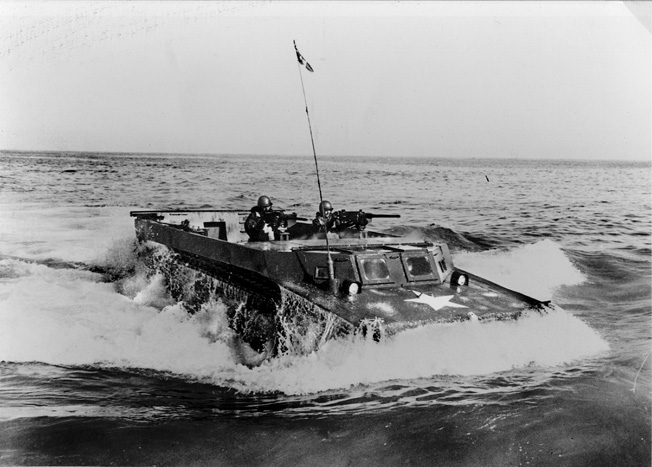

Major Kaluf was able to convince Roebling to construct a completely new Alligator that satisfied initial military specifications. A fourth-generation Alligator was delivered in May 1940 and the redesigned militarized (fifth-generation) Alligator was delivered to the Marine Corps five months later. It had a far sleeker and decidedly more military appearance. It was powered by a Lincoln-Zephyr engine rated at 120 horsepower. Combined with other design improvements, this new Alligator produced a speed of 29 miles per hour on land and just short of 10 miles per hour in water. Following extensive testing at Quantico and participation in a fleet exercise in the Caribbean, the Navy Department asked Donald Roebling if he could make this model of what they now termed an “Amtrak” (Amphibious Vehicle-Tracked) stronger by constructing it from steel.

Lacking the capability to produce Alligators in volume, Roebling, due to some combination of friendship and confidence in their ability, employed the Food Machinery Corporation (FMC) plant in Dunedin, Florida. FMC made agricultural and food-processing equipment, but with war clearly on the horizon agreed to work with Roebling and the government to develop and build a steel-hulled Alligator.

Landing Vehicle Tracked (LVT)

Within just a few months, two steel Alligators were delivered for military evaluation. When a $3.3 million government contract for 200 more amtraks followed, FMC began immediate conversion of its new citrus sprayer and turbine pump manufacturing plant in Lakeland, Florida, to the exclusive construction of the LVT (Landing Vehicle Tracked).

This first military Alligator was identified as LVT-1. It had no armor plate and only light armament consisting of two .30-caliber air-cooled machine guns. An enclosed two-man crew cab was forward on the hull. Instrumentation and controls were rudimentary. Movement was accomplished very much as in automobiles of the era. The right foot operated the accelerator and the left foot operated the clutch as the transmission was hand-shifted through a series of three gears. Push the reverse levers forward, and the LVT backed through the same three-speed transmission. Two steering levers controlled the power output drive-track clutches and brakes on land and water. Full forward on both levers engaged the tracks at full power. The lever on the side to which a turn was to be made was pulled part of the way to slow or full back to stop that track. The opposite track maintained power to drive the LVT through the turn on land or water.

The LVTs Find Combat

The first overseas deployment of a LVT detachment was in May 1942, when Company A, 1st Amphibian Tractor Battalion, 5th Marines left Norfolk for New Zealand. It arrived just in time to be included in the plan for landings on Guadalcanal and the adjacent islands of Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo. The Alligator LVT-1 saw use in that operation, which commenced on August 7, 1942, but only as a logistical support vehicle carrying cargo and ammunition to the beach and evacuating wounded.

The first actual combat use of the LVT-1 was at Tarawa November 20, 1943. Of 125 amtraks deployed only 35 were still operational at the end of the first day. This made it obvious the LVT-1 was not quite ready to assume an offensive role. Yet, its ability to deliver troops directly to the shore was of such critical importance that it gained the support needed to fund a succession of improved models.

The larger and more powerful LVT-2 Water Buffalo entered the war as a lightly armored 32,500-pound assault amphibian at Bougainville on November 1, 1943, followed by Kwajalein Atoll in February 1944. It carried a crew of six and was armed with machine guns and a 37mm howitzer mounted in a tank-type turret. It still had no ramp, making it necessary for the 24 troops it could carry to continue going over the side and recover from an eight-foot drop to the ground to meet the enemy.

Island Hopping With the LVT-3 and 4

The LVT-3, which was to have a much improved drivetrain, remained in development while the LVT-4, a larger and more powerful version of the Water Buffalo, finally equipped with a stern ramp to deploy troops, landed at Saipan June 15, 1944. Providing clearing firepower was the new, 20-ton LVT-A4 armored amtrak carrying a 75mm howitzer. These two vehicles performed admirably at Saipan and in the invasions of Guam and Tinian in July, Moratai and the Paulaus in September, and Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945.

On Easter Sunday of 1945, the Japanese at Okinawa were introduced to the 38,600-pound stern ramp LVT-3 Bushmaster. Its two Cadillac V-8 engines produced a combined 220 horsepower. They were coupled to the tracks with a Borg-Warner automatic-shift fluid-drive transmission designed to maintain peak power under all conditions.

Like the LVTs themselves, the tactics for deploying them were continually refined. LVTs that had required an hour or more to unload from a ship were now launched in just minutes from the bow doors of the Navy’s versatile LST (Landing Ship, Tank). Communicating by radio, the launched LVTs maneuvered into a standard assault formation line of departure.

At the signal, all LVTs headed for the beach with the invading troops crouched below the protective sides of the open cargo compartment. The cacophony of roaring engines, bursting shells, and bullets pinging off the armor combined with the pitching and rolling that quickly produced seasickness, caused most of the troops to welcome the crunch of contact with the beach, despite the fact it signaled they were about to enter the fury of battle.

LVTs would see service in all branches of the services and in all theaters in World War II, but their greatest contribution to victory was the role they played in securing the Pacific islands so strategically critical to any invasion of the Japanese mainland. These islands could be shelled from the sea and bombed from the air for days, but in the end they had to be secured by ground forces landed from the sea. Landing boats could not circumvent the reefs and sandbars that fringed most Pacific islands. This forced the landing troops to disembark and wade long distances to the beach, often under heavy enemy fire. Without the ability of the tracked LVTs to land troops directly on the shore, causalities in the Pacific would have been much greater.

20,000 LVTs

Nearly 20,000 LVTs were produced during World War II. When the atomic bomb ended the war, negating the need to invade the Japanese mainland and what would have without question been the war’s most horrendous and costly campaign, surplus LVTs were eagerly accepted into the armies of other countries. Hulking descendants of the original Alligator with far advanced engine, drive, navigation, and weapons systems continue to serve the Marines to this day.

Donald Roebling died August 29, 1959, from complications following gall bladder surgery. His multifaceted legacy is one of extreme generosity with his time and wealth to positively influence the interests of mankind—but never without emphasis on his invention of a machine meant for humanitarian purposes that saved military lives and helped shorten a war.

In 1984 the prototype Alligator was moved from the Marine Reserve Center in Tampa to the United States Marine Corps Museum at Quantico, Virginia, where it was placed on display following an extensive restoration.

Is there any information on Company “C” 4Th Motor Transport Battalion, Attached To 23Rd Marines, 4Th Marine Division, F.M.F., Camp Pendleton, Calif, during WWII?