by Sam McGowan

If there is an American combat airplane that has achieved an ill-deserved reputation, no doubt it would be the much-maligned Bell P-39 Airacobra, a tricycle landing gear single-engine fighter whose reputation was greatly overshadowed by the more famous, and of more recent design, Lockheed P-38 Lightning, Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, and North American P-51 Mustang. (Read all about these and other planes from the Second World War inside the pages of WWII History magazine.)

In the minds of some, the P-39 was a practically worthless airplane, with few redeeming features.

They consider the nickname used by pilots of the Bell P-39 Airacobra—Peashooter—a term of derision that implies the airplane’s effectiveness as a fighter. But the P-39’s many detractors ignore the reputation of the Airacobra with the Soviet Air Force, and the important role it played in the Southwest Pacific Area of Operations in 1942, when P-39s were the only fighters available, thanks at least in part to the decision not to use them in large numbers in the European Theater. And if considering overall capabilities instead of concentrating solely on certain features, the P-39 comes off as a capable fighter.

Making Up for Low Altitude Performance

While it is true that the P-39 lacked the high altitude performance needed to excel as an interceptor, it had other attributes that made it a successful combat airplane. When Bell Aircraft was designing the single-engine fighter, U.S. defense plans centered around the possibility of repelling naval attacks and possible landings on American shores. Little attention was paid to the high altitude performance needed to intercept formations of enemy bombers, because the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans provided the best possible defense from foreign attack. No country possessed the capabilities of mounting a transoceanic air attack in 1935, and the United States had yet to seriously consider the possibility of combat in Europe or around what would come to be known as the Pacific Rim.

Consequently, the U.S. Army wanted airplanes that were more suitable for attacking invading ground forces and/or naval landing parties than for intercepting enemy formations at high altitude. So, Bell designed its new interceptor around the Allison V-1710 engine without turbochargers—even though the engine in the prototype was turbocharged—and concentrated more on low altitude maneuverability and firepower than high altitude or climb performance.

Thus, the Airacobra featured short wings that allowed it to turn on a dime but greatly reduced its climb performance due to their overall area. Its best speed of 368 miles per hour was reached at 13,800 feet. At higher altitudes, performance began to degrade rapidly and the airplane had reached its maximum ceiling by the mid-20s range. Unfortunately, developing events in Europe were soon dictating air combat at altitudes over 30,000 feet.

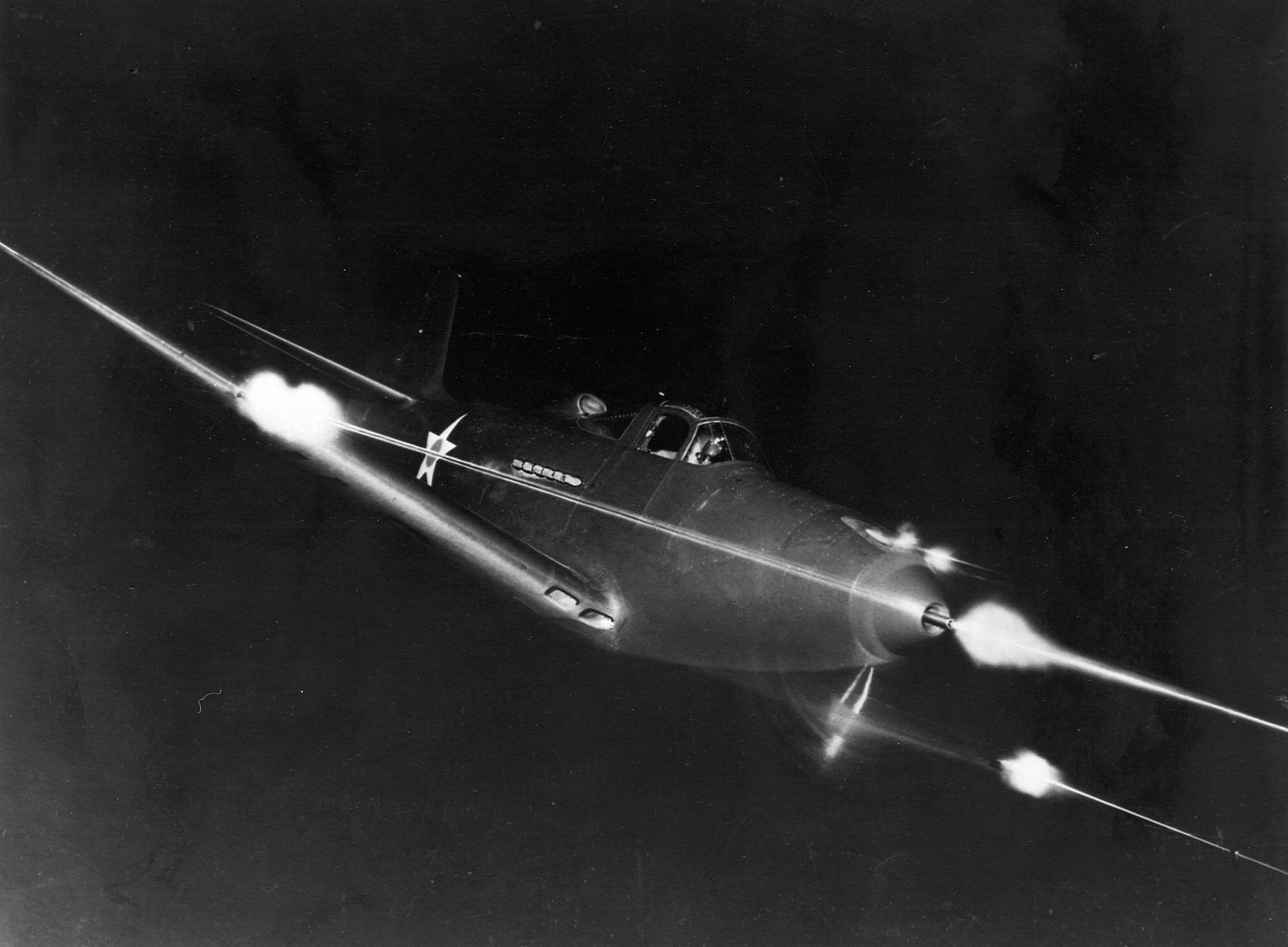

An Effective Cannon With a Unique Configuration

The Bell P-39 Airacobra was also unique. Not only was it the first operational tricycle landing gear single-engine fighter, it was the only U.S. manufactured military airplane with the engine located in the center of the fuselage instead of in the nose. The P-39’s pilot actually sat in front of the engine, directly over a drive shaft that was modified so that a 37mm cannon fired through the propeller hub. It was this feature that led to the peashooter nickname, a term that was already in wide use in the Army Air Corps long before P-39s entered combat in the Southwest Pacific. The cannon was an effective weapon that could be deadly against bombers and ground targets, although the 37mm shell was a bit small to do much damage to heavier armored vehicles such as larger tanks.

Additional armament consisted of a pair each of .30-caliber machine guns mounted on top of the nose, synchronized to fire through the propeller blades. Two .50-caliber machine guns were added in the wings for combat. The Airacobra’s armament was eventually increased to six .50-caliber machine guns, two on the nose and two in each wing, and the 37mm cannon, a powerful package that made the P-39 an ideal ground attack airplane. Hard points were added to allow the Airacobra to carry bombs. But it was not in the ground attack role that P-39s initially saw service.

Enjoyed by Some Pilots, Not by Others

The Airacobra was one of the first American fighters to be exported; an export version designated as the P-400 was produced for delivery to British forces, who called it the Airacobra I. The first P-400s were produced to fill a French order, but none had been delivered before France fell. Britain picked up the French orders for American aircraft, including the P-400. Compared to the P-39, the P-400 was lightly armed, with only a 20mm cannon and two .30-caliber machine guns mounted in the wings instead of on the nose. Beginning in October 1941, Royal Air Force fighter squadrons operated P-400s for a short time, but they were soon withdrawn from combat due to their lack of high altitude performance.

After having become accustomed to high altitude combat during the Battle of Britain, the RAF pilots were not impressed with the Airacobra, and the airplane’s disparaging reputation began (or at least that is the point at which some historians have decided it was a worthless airplane. Actually, many of the pilots who flew the P-39 thought it a joy to fly.)

Recommissioned in Australia and North Africa

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the U.S. took over the British contract. A large number of reclaimed P-400s saw service with U.S. Army Air Corps squadrons that were sent to Australia, where they proved inadequate as interceptors, while others served in North Africa. The Airacobra’s problems were due to the combination of the design’s short wings and the lack of a supercharged engine, which kept it from attaining more than medium altitudes.

Instead of electing to correct the problems and trying to turn the Airacobra into a high altitude interceptor, the United States Army decided to forego the addition of superchargers since new, high performance fighters such as the P-47 and P-38 were entering production. Those who flew the P-39 and P-400 would have to take them into combat as they were.

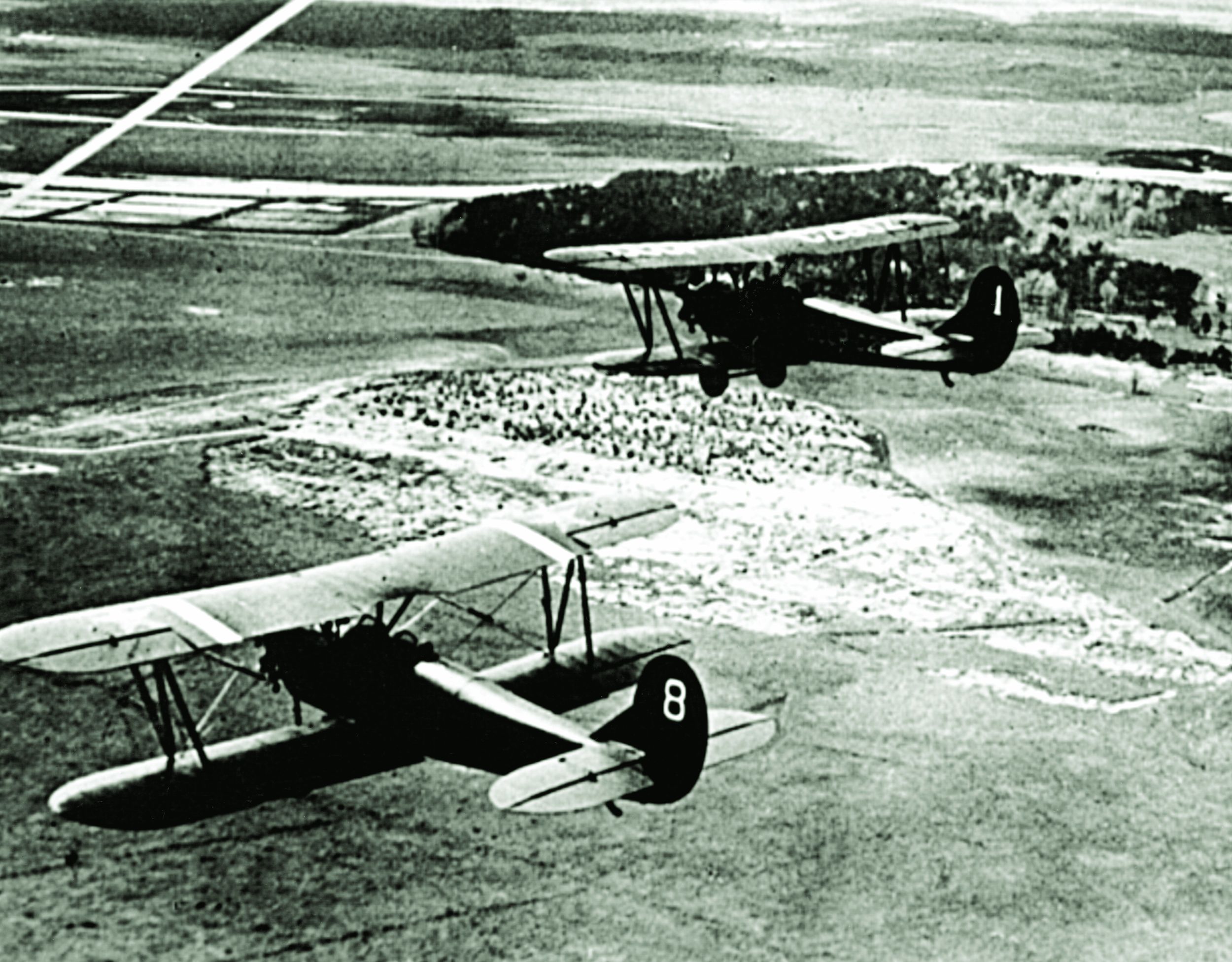

Airacobras went into combat without modifications that might have made them more suitable as interceptors for another reason. Along with Curtis P-40s, they were the only American-built fighters available in large numbers in early 1942 that were not obsolete, and they were badly needed in the Pacific.

Setting Sail for Manila

Immediately after Pearl Harbor, the Army Air Corps began dispatching Airacobra-equipped squadrons to Australia. The 35th Pursuit Group had actually set sail for Manila two days before the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the men of two of its squadrons were already there flying P-40s, but no Airacobras had reached the Philippines before the December 8 attack (the “pursuit” designation was changed to “fighter” when the Army Air Forces reorganized in early 1942).

After the attack the group headquarters returned to the U.S. for a few weeks, but was in place in Australia shortly after the first of the year. Many of the pilots who had gone to the Philippines rejoined the group there. The 35th Group’s squadrons began equipping with P-400s that had been delivered from the United States by ship and went into training for combat. The 8th Pursuit Group also moved to Australia and its P-39s were soon operating from forward bases in New Guinea.

Those two groups, along with the P-40 equipped 49th Pursuit Group, would constitute the nucleus of the soon-to-be-famous V Fighter Command, which would ultimately gain air superiority in the Southwest Pacific. But with the Airacobras, the pilots of the two groups would be at a distinct disadvantage in their initial role as interceptors. Early on, the Army planned to send Airacobras to England with the Eighth Air Force, and two P-39 groups were assigned to it in early 1942 when the Eighth was organized. At the time, the planned mission of the Eighth Air Force was to support the Allied landings in North Africa that were scheduled for later in the year.

Training With Bell P-39 Airacobras

The Allied defeat in Java, followed by the threat to the United States as the Japanese fleet steamed toward Midway Island, led to a cancellation of the planned invasion, although a revised plan was reinstated after the U.S. victory at Midway. The new Eighth Air Force lost most of its combat groups to the Pacific, then was selected to reorganize and go to England as the British Isles Air Force.

Two groups, the 31st and 52nd, trained with P-39s, but the problem of flying the single-engine fighters across the North Atlantic led to a decision to send the pilots and ground personnel to England by ship and to leave their airplanes behind. When they got to England, the two groups re-equipped with British Supermarine Spitfires. The lightweight Spitfires cost considerably less than the more rugged Airacobras.

Another group, the 81st Fighter Group equipped with P-39s and former RAF P-400s in England, then deployed to North Africa, as did the 68th Observation Group. The 99th Fighter Squadron, the original Tuskegee Airmen, trained in the United States with P-39s before going overseas and flew them in combat in North Africa and the Mediterranean.

Defending Australia

By mid-March 1942, ninety Bell P-39 Airacobras and more than 100 of the P-400 derivative had been shipped to Australia. The P-39s went to the 8th Fighter Group while the 35th, which was reorganizing in Australia with pilots who had come out of the Philippines, received the P-400s. Five squadrons of P-39s were also distributed across the South Pacific, with squadrons at Fiji, Christmas Island, Canton, New Caledonia, and Palmyra. Four of the five squadrons, the 67th, 68th, 70th, and 339th, would be formed into the 347th Fighter Group in October 1942, with the group headquarters on New Caledonia until it moved to Guadalcanal late in 1943. Another squadron of P-39s was part of the 18th Fighter Group. Some South Pacific squadrons would still be flying P-39s in early 1944. A P-39 squadron was also dispatched to Alaska. But it would be in New Guinea that P-39s would enter combat, and it was there and in the nearby Solomons that they would play their greatest role with U.S. forces.

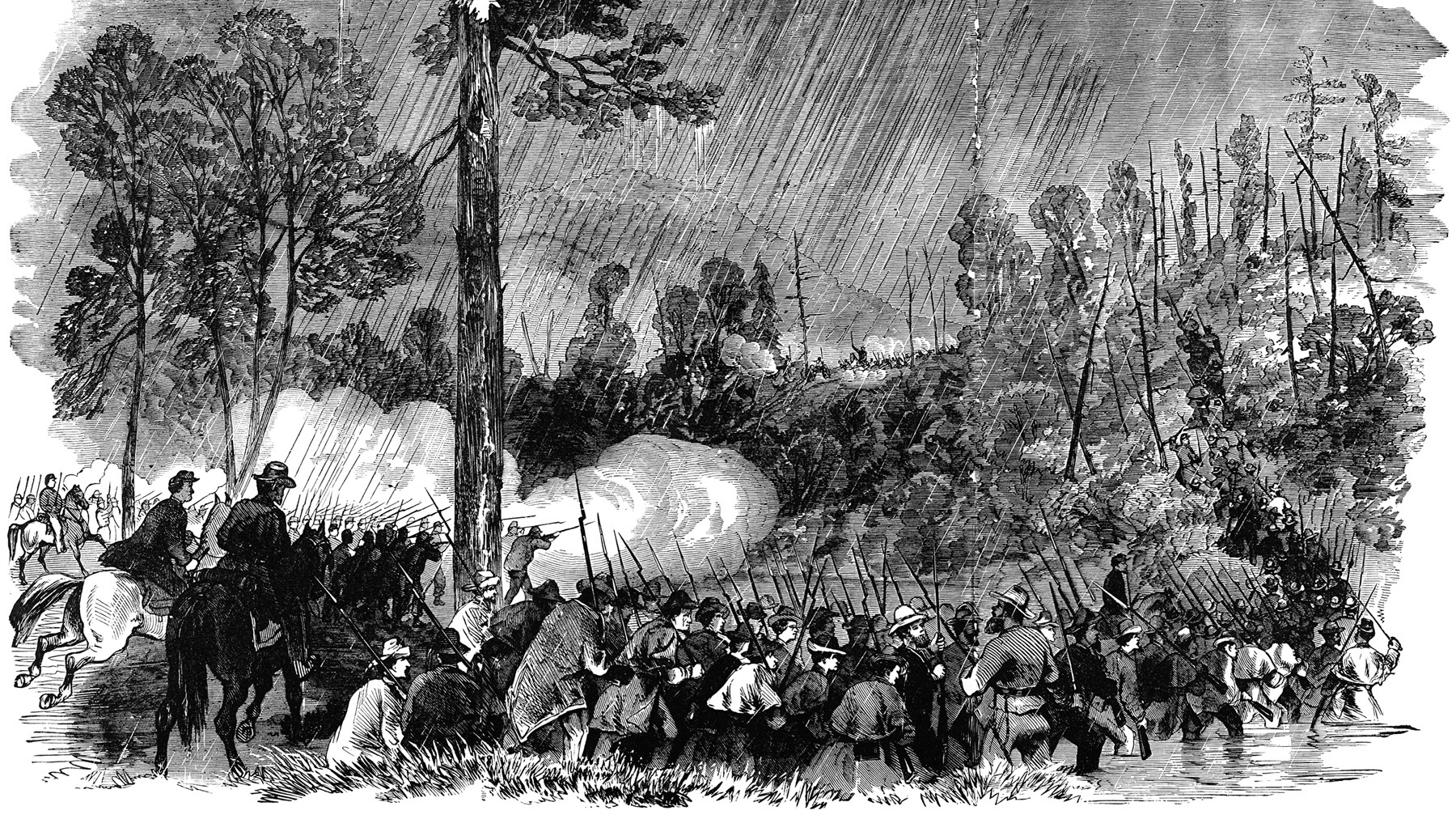

In the spring of 1942, the mission of Allied air forces in the Southwest Pacific was the defense of Australia. Immediately upon his arrival there from the Philippines, General Douglas MacArthur decided that the battle line should be drawn in New Guinea. The original Allied plan had been to withdraw south of a line in Central Australia and organize a defense of the more populated southern half of the country, but the idea of giving up more territory to the Japanese was anathema to MacArthur.

Holding Their Own in the Philippines

The loss of the Philippines had affected him deeply, and his every effort was devoted to offense, rather than a continuing retreat deep into Australia. He elected to defend Australia by holding the line in New Guinea until he had sufficient strength to go on the offensive and drive the Japanese off the huge island. While the 49th Fighter Group took its P-40s to Darwin, which had come under Japanese air attack from Java, an advanced echelon of the 8th Fighter Group moved its P-39s in April into Port Moresby on the south coast of Papua, New Guinea, and immediately began combat operations.

Although the pilots of the 8th Fighter Group were flying an airplane that lacked the performance to meet the Japanese at high altitude, their P-39s could hold their own at the lower altitudes and they were led by pilots with combat experience in the Philippines—where Army Air Corps pilots and gunners had destroyed as many Japanese aircraft in the air and on the ground as had been lost. Lieutenant Colonel Boyd “Buzz” Wagner was one such commander.

As a young lieutenant flying P-40s, he had quickly achieved a reputation for aggressive action in daring attacks on Japanese airfields in the first weeks of the war. An aeronautical engineer by training, he knew the capabilities of the Japanese fighters as well as those of his own aircraft, and his skill and knowledge quickly put itself to good use in New Guinea.

On the afternoon of April 30, 1942, Wagner led a formation of 26 Airacobras on their first combat mission, a strafing of the Japanese airfields and fuel dumps at Lae and Salamaua.

Facing the Japanese Air Force

They encountered Japanese fighters and engaged in an intense dogfight. Four P-39s were lost, but the Americans claimed three Japanese fighters shot down. Unfortunately, the losses were especially severe since eleven P-39s had failed to reach Port Moresby during the flight up from Australia and every airplane was badly needed. But there was a bright spot—all of the P-39 pilots were rescued and only one was seriously injured. In two months of combat in New Guinea, the 39th squadron shot down 12 Japanese aircraft for a loss of nine of their own—but did not lose a single pilot. The only serious injury came when a pilot bailed out at high speed and struck his airplane’s surface.

Intercepting incoming Japanese bomber formations was the pressing concern of the force at Port Moresby, but the P-39s and P-400s that constituted the bulk of the air defenses lacked the performance to reach the 22,000-foot altitudes at which the Japanese bombers came over in time to intercept them. It was not that the Airacobras were vulnerable to Japanese fighters. They simply lacked the climb performance to reach the altitudes at which the Japanese were operating!

During the month of July, P-39s only managed to intercept the Japanese formations four times during nine air raids. The P-40s had somewhat better high-altitude performance and attempted to intercept the Japanese formations, but most of their efforts were equally unsuccessful due to a lack of time to gain enough altitude. Furthermore, the P-40s of the 49th Fighter Group were needed to defend Darwin, which was becoming a major Allied base. So, the fighter role in New Guinea remained the responsibility of the P-39s.

Suited for a Ground Attack

If the Japanese dropped to lower altitudes, Bell P-39 Airacobras were more than up to the task of knocking them down, but a more effective method was to catch the enemy aircraft on the ground and take advantage of the P-39’s cannon and machine guns in strafing attacks. The P-400s were particularly ineffective as interceptors due to their lack of heavy armament, but with racks for bombs they were well suited for ground attack. On August 8, a 32-plane formation struck Japanese supply dumps on the north side of the Owen Stanley Mountains in one of the first ground attack missions in the theater.

On August 22, an advance element from the 67th Fighter Squadron arrived at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal with five P-400s. The remainder of the squadron arrived five days later, and the Army pilots began operations under the control of Marine Aircraft Wing One and became part of the Cactus Air Force. After initially attempting to intercept Japanese aircraft, the squadron only had three airplanes still in commission after only four days of operations.

I find your “Peashooter” tag EXTREMELY BOGUS!

All production Alison V-1710 engines had a GEAR driven single speed centrifugal flow turbosupercharger mounted at the usual rear of the engine block location. It was designed to be the second stage to the EXHAUST driven centrifugal flow turbosupercharger (since called TURBOCHARGER) combination that had been fitted to the P- 38 Lightning. The only V-1710 designed without a supercharger was the experimental was the model proposed for the new dirigibles being developed for the U S Navy. (airships routinely flew at lower altitudes); it was never produced since the Navy opted for their favored air cooled engines.

The P-39 was also employed in the U S occupation of Iceland, as a lower altitude air defense/ anti invasion fighter ( along side the P-38, in the high altitude interceptor role) in 1942. Coincidently, both aircraft had V-1710 engines, tricycle landing gear and cannon and machine gun armament. Contemporary photos show

both aircraft types on snow covered hard stands in Reykjavik…

The Airacobra played an important part in the Soviet Union’s defense against the Nazi invasion in 1942-3. It’s good lower altitude performance and M-4 37mm cannon with high explosive ammunition, allowed it to excel against the German fighter and attack aircraft over the battle front (the Bf-109 had little or no advantage over the P-39 below 10,000 ft) a, as well as in close air support and interdiction against artillery, supply and transport concentrations.