By Eric Niderost

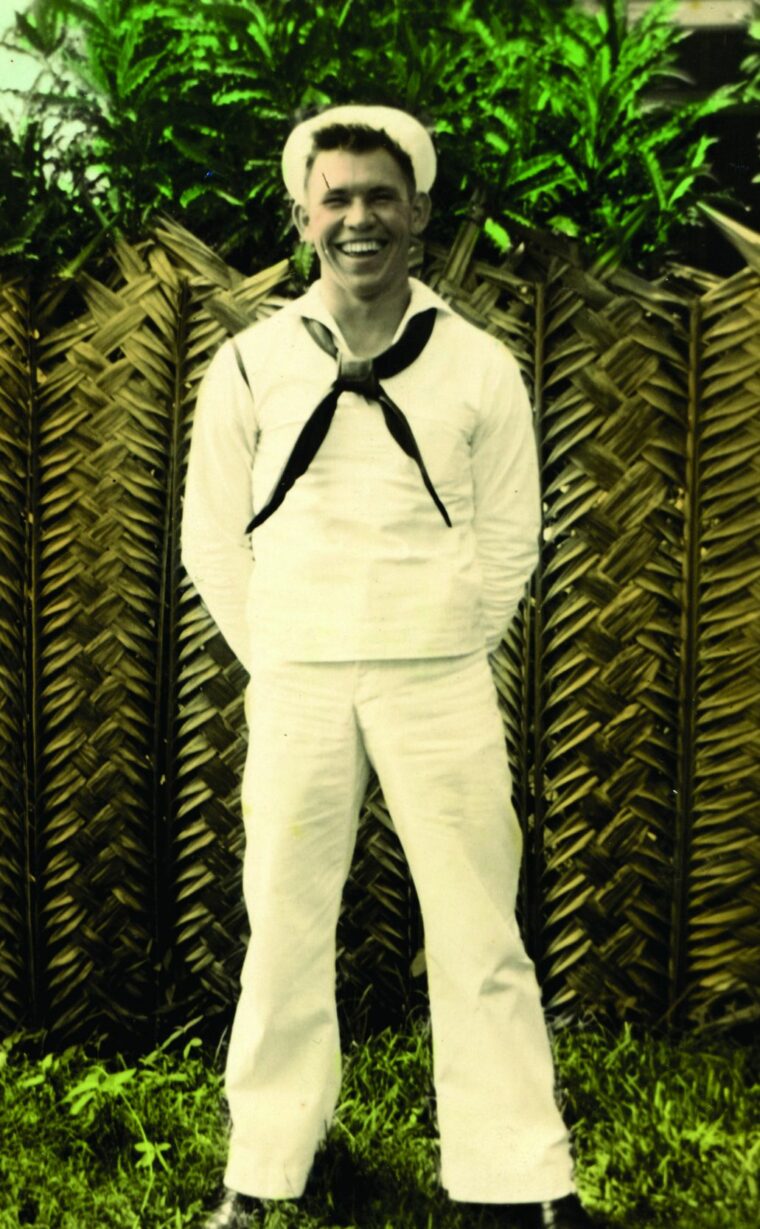

When Howard Brooks joined the United States Navy in 1939, the 20-year-old farm boy from Tennessee had no idea that he was going to experience one of the most harrowing adventures of World War II. In the early months of the war, Brooks and his fellow crewmen aboard USS Houston fought heroically against overwhelming odds, only to have their ship blown out from under them at the Battle of the Sunda Strait in February 1942. But the battle, horrific as it was, marked the beginning, not the end, of their ordeal. Houston survivors were captured by the Japanese and shipped to Burma, where they became slave laborers on the notorious “Railway of Death,” made famous by the Academy Award-winning (if rather inaccurate) 1957 movie, The Bridge on the River Kwai.

Houston (CA 30) was a heavy cruiser that became celebrated in the 1930s as President Franklin Roosevelt’s favorite warship. She was a thing of beauty, sleek and powerful as her graceful prow sliced though the water at speeds upward of 33 knots. Houston hosted Roosevelt four times, carrying him and his staff on long holiday cruises in 1934, 1935, 1938, and 1939. As the president later remarked, “I knew that ship and loved her. Her officers and men were my friends.”

Houston was in many ways a microcosm of the Depression-era Navy. Her crew was highly trained, her officers competent and professional, but the ship’s overall fighting ability was weakened by “penny-wise, pound-foolish” budget cuts imposed by Congress. As the flagship of the Asiatic Fleet in the early 1930s, Houston was a familiar sight in Shanghai and other Far Eastern ports of call. She returned to Asia in March 1941, just as Japan and the United States were teetering on the brink of war.

Houston was in the Philippines when war finally broke out. In January 1942, she became part of a hastily assembled and poorly coordinated combined Allied fleet. She escaped destruction several times, mostly from enemy air attacks, but her luck ran out at the end of February, when the Allies engaged an overwhelmingly powerful Japanese task force in the Battle of the Java Sea.

The battle was an Allied disaster, but Houston and the Australian light cruiser HMAS Perth managed to escape the debacle. Ordered to the Indian Ocean, the pair was caught by the Japanese in Sunda Strait. Perth was sunk by torpedoes, leaving Houston to fight alone in an epic, one-sided battle against an entire Japanese task force. After fighting desperately and valiantly, Houston was sunk. Of her roughly 1,100 men, only 360 survived the battle.

Howard Brooks was one such survivor, and eventually he found himself assigned to the infamous Thailand-Burma Railroad, the “Railway of Death.” The 257-mile-long rail line passed though some of the roughest terrain in the world, a nightmare of thick jungles, mountainous ridges, and treacherous streams. The tropical climate was unforgiving, and the half-starved, exhausted prisoners were all too susceptible to cholera, typhoid, malaria, and beriberi. Some 61,000 Allied POWs were slave laborers on the railway, including 30,000 British, 18,000 Dutch, 13,000 Australians, and 700 Americans. Of that number, perhaps 16,000 Allied prisoners died of disease, overwork, and maltreatment by vicious Japanese guards. Another 200,000 native Asian workers also were forced to labor on the line, and 80,000 of them lost their lives as well. Understandably, Brooks has vivid memories of the Railway of Death.

“A heavy cruiser was like a hotel, and I enjoyed it.”

Eric Niderost: Perhaps you could start by giving us some of your background.

Howard Brooks: I was born October 30, 1919, in Greeneville, Tennessee. I grew up on a farm, where we raised mainly tobacco and cows. I was one of eight children, but originally there were three more, two boys and a girl. They died in the great flu epidemic.

EN: Why did you join the U.S. Navy?

HB: One older brother had joined the Navy in 1927, and I was influenced by him. After graduating from high school in June 1938, I stayed on the farm for a time. On September 3, 1939, I went to town and signed up for the Navy. A few days later I got on a bus for the naval training center in Norfolk, Virginia. After boot camp I was sent to San Diego, where I arrived on New Year’s Day, 1940.

EN: Eventually you were sent to Hawaii, where you were given the heavy cruiser USS Houston as your permanent assignment. In time you became a ship’s electrician. What was life like aboard the Houston?

HB: A heavy cruiser was like a hotel, and I enjoyed it. After work or duty hours, a group of friends would chip in and go down to the gedunk [shipboard store] for some pogey bait [snacks], usually Coke and some kind of chips. We’d go to some breezy place topside and all sit down on a wool blanket, and then my best friend, Arnie Arnesen, would play the accordion. Our favorite place was the searchlight station, which was on our mainmast.

EN: How was the daily work routine aboard Houston?

HB: It was all spit and polish. All painted surfaces were kept squeaky clean, and all brass polished almost daily if you were at sea. We had lots of wood decking on the fo’castle quarter deck and fantail, and these would be holystoned first thing daily. Of course, there were a lot of gunnery drills.

EN: In the last months of peace, Houston’s skipper was Captain Albert Brooks, an Annapolis graduate who was known to do things by the book. What were your impressions of him?

HB: A fine man. I never really saw much of him until our first action on February 4, 1942. If we were not at battle stations, he’d come around and say a friendly word.

EN: Admiral Thomas C. Hart ordered most of the Asiatic Fleet to withdraw from China. The Philippines, then a quasi-colonial possession of the United States, would be the fleet’s main base. Houston was a magnificent ship, but her beauty and power hid some flaws. She needed modernization, and her fire control equipment was obsolete.

HB: Yes, and we had faulty antiaircraft ammunition, and we didn’t have the latest radar equipment. Yet, in my 22-year-old mind I felt very confident that we were going to have a short and successful war. We may not have been ready in a material way, but we were ready in a way that counted

“The [500-pound] bomb came though the deck at an angle, then entered the turret barbette and exploded immediately.”

EN: After the war broke out, Houston was mainly employed in convoy escort duties. But things changed on February 4, 1942, when Houston joined other Allied ships to try and intercept a Japanese force at Makassar Strait, north of Java. But then, formations of Japanese twin-engine bombers appeared. What was your battle station?

HB: I was with the after-damage control party. Our station was on the second deck in the area very close to the barbette of Number Three Turret [one of the eight-inch battery turrets].

EN: It was said that Captain Brooks maneuvered the 600-foot cruiser “like a motorboat,” dodging bomb after bomb. But finally, the Japanese scored a hit.

HB: The [500-pound] bomb came though the deck at an angle, then entered the turret barbette and exploded immediately. Most of the blast was inside the turret, but there was still enough outside to kill all of the damage-control party but two. I was one of them.

EN: How did you survive?

HB: Just a short time before the bomb hit, Boatswain Joseph Bienert, warrant officer and head of our damage party, had been asked to send two electricians to check on a problem on one of the five-inch ammo hoists. He sent me and Larry Wargowsky, and we found that the electrical problem was an overheated ammo hoist motor. But when we were there we heard over the PA system that a bomb had hit Turret Three, so we rushed back to our station. Most of the guys had been killed by concussion, but there was Bienert, sitting with most of his insides lying on his lap. He was conscious, aware, and talking, and when we were trying to put him on a stretcher, he asked us to leave him alone and help someone else.

EN: Houston had 48 dead and 20 wounded from that bomb blast. The light cruiser Marblehead also had been badly damaged in the same air attack.

HB: About the same time that we were hit, Marblehead was hit by one bomb on her fantail. There was damage to her steering gear and rudder, with about 13 killed and two dozen wounded. Houston and Marblehead headed to Tjilajap [Java] by way of Bali Straits. On our way to Tjilajap, a big work party was busy making plain wooden caskets. Twelve were from the damage-control party; the rest were from the turret crew.

EN: Once at Tjilajap, then part of Netherlands East Indies, there was an attempt to effect repairs. There was also a moving funeral ceremony for the casualties.

HB: A big dock crane repositioned Number Three Turret onto its base and spot-welded it in places so that it would be stable. It was at the shipside ceremony for our dead that I saw Admiral Hart, the only time I ever saw him. After the ceremony, the caskets were loaded onto what looked like Dutch Army trucks. The severely wounded from Houston and Marblehead were taken by Dutch medical vehicles to Dr. Wassell’s hospital [Dr. Corydon Wassell, portrayed by Gary Cooper in the Cecil B. DeMille movie The Story of Dr Wassell]. I didn’t actually go ashore at Tjilajap.

“Houston was alone in the midst of enemies, firing in all directions at her attackers.”

EN: Admiral Hart commanded the Asiatic Fleet before the war. He was the one who had to decide if Houston would stay in a deteriorating Southeast Asian Theater or head home for repairs. With some reluctance, but with Captain Rook’s wholehearted approval, he agreed Houston would stay.

HB: I have always wondered who made the final decision for the Houston to remain out there. Rooks and Hart knew beyond a shadow of a doubt that the situation with the Japanese was a totally hopeless one. The Japs owned everything from Shanghai to Singapore, and if they tried, they could have landed anywhere in northern Australia.

EN: Houston and Perth managed to survive the Battle of the Java Sea, an Allied debacle that saw the loss of two cruisers and three destroyers. Worse was to follow. Before going down on his flagship DeRuyter, Dutch Admiral Karl Doorman had ordered Houston and Perth to retire to Batavia [now Jakarta].

HB: We arrived at Tanjung Priok [Batavia’s port district] before sunset, tied up to a pier, and were soon taking on oil. I remember sitting on the searchlight platform looking down at the ship’s band as it was playing on the fantail. As I sat there, I heard a plane that sounded like it was near. As I looked up, it came directly over us, and I could see the big red sun under each wing. We didn’t see the plane anymore, but at about 11 o’clock that night we headed for the Sunda Strait.

EN: Houston and Perth were ordered by Dutch Admiral Conrad Helfrich to report to Tjilajap, on the other side of Java. This meant leaving the Java Sea and breaking out into the wide Indian Ocean via the Sunda Strait, the passage between the islands of Java and Sumatra.

HB: I remember, in our small talk, we all were looking forward to entering the Indian Ocean. My feeling was, we’re going to out of range of those planes that have been harassing us for so long. We’ll be safe. On the evening of February 28, I was fast asleep on the fantail-starboard, on my blanket near the water.

EN: The two cruisers had the bad luck to run into a major Japanese invasion effort, a landing force consisting of 56 transports and auxiliaries carrying the Japanese Sixteenth Army and its supply train. But the transports were guarded and screened by a formidable array of Japanese vessels, including two cruisers, one light cruiser, and three divisions of destroyers. How did the battle start from your perspective?

HB: The first thing I heard was the battle station gong. It was a little after 11 pm, and Perth had opened fire on something—at least we thought it was Perth. Houston picked up speed, and you could tell the captain [Rooks] was zigging and zagging to avoid torpedoes. We were doing this for a while—it seemed like minutes—when all hell broke loose. Strong lights began to shine on us, and we were keeping up a good speed and doing a lot of turning.

EN: After the gallant Perth was torpedoed and sunk, Houston was alone in the midst of enemies, firing in all directions at her attackers. The Japanese fired shells, launched torpedoes, and even raked Houston with machine-gun fire. What were the ship’s last moments like?

HB: I could feel the ship shudder, and at the same time I could hear what sounded like machine-gun bullets hitting the sides of the ship, so I disappeared real quick down the ladder that was nearby. A short time later, the PA system announced a torpedo hit forward-starboard, and a moment after that, there was another shudder. This time it was starboard-midship—the forward engine room.

“The PA sounded “Abandon ship,” and then, ‘Cancel abandon ship.'”

EN: Houston went down fighting, and by some accounts managed to hit three Japanese destroyers and sink a minesweeper

HB: The last thing I saw before going below was that searchlight on us, and I remember hearing an airplane overhead, and of course there was what sounded like machine-gun fire and heavier gun fire, too. The PA sounded “Abandon ship,” and then, “Cancel abandon ship.” I was confused, but continued to look for a life jacket, when over the PA came the final and definite call for “Abandon ship.” By this time I had reached the portside-aft and, sure enough, I found a life jacket. I could see that most of the ship from the quarterdeck forward was burning, the biggest fire coming from the bridge forward.

EN: The second order to abandon ship was at 12:33 am on March 1, 1942. The ship was in her death throes, listing hard to starboard and settling by the bow. How did you get into the water?

HB: Well, I did a stupid thing—I removed my shirt, pants, and shoes before putting on my life jacket. I had to get off the ship, and I figured the clothes I just removed would have become waterlogged and pulled me down. I jumped into the water, and I don’t know how many degrees the list was, but it did help me. As soon as I was in the water, I saw there was a life raft nearby, so I grabbed onto one of the rope side loops. When I grabbed on, I breathed a sigh of relief, since I was a nonswimmer.

EN: Did you look back toward the ship?

HB: Houston was all lit up by Japanese searchlights and, as we floated away from our sinking ship, she was engulfed in flames from the boat deck to the stern. The stern was fast approaching sea level by that time, and any guys that did not get out of the forward powder or ammo magazines were being drowned or suffocated. Those still on deck were being sprayed with machine-gun fire from Japanese tin cans and smaller torpedo boats. As we floated and watched Houston burn, those Japanese vessels were also firing into the water all around the sinking ship where we were.

EN: Houston’s final moments were at hand.

HB: As the fantail slowly disappeared into the brightly lit sea, our “Old Glory” still flapped defiantly to the last. To this day I have never seen a more beautiful display of a flag.

“We were put in a camp that had a boundary marked with a string attached to small sticks.”

EN: What happened immediately after Houston went down?

HB: Well, I remember there were several severely injured men in the center of the raft, and three other guys hanging onto the sides as I was. Later, we began to float near some Japanese transports, so close that we could hear them talking. Not long after that we saw what looked like a whaleboat being paddled by four Japanese sailors. They came near and took a good look at us, but then they kept going. We surmised they saw all the badly wounded guys and didn’t want to be bothered with us.

EN: You floated around for three days.

HB: Now, during all that time we were floating along we could see the shore line—at times we would be so near we could see the trees very plainly, but the current would always take us out of reach. On the second day we lost one of our injured sailors. He was gently slid into the deep on the morning of the third day. The other two wounded men followed the first. A lively breeze was blowing, and we were five hungry, thirsty, and awfully sunburned guys. The breeze was pushing us toward shore, and one of the guys weakly said he thought his foot had touched a rock. Sure enough, in just a very short time all of us were lying down on the sand, stretching our weak, hungry bodies.

EN: After capture on Java, you and other Houston survivors were taken to Batavia and placed in the so-called “Bicycle Camp.” There were occasional beatings, but on the whole—especially when compared with what was to come—conditions were fair.

HB: The food was nothing to write home about, but acceptable. They took us out on work details. Most of the work I had to do was at the Dutch Shell warehouses, where we handled truckloads of grease and oil. But after a few months [October 1942] the Japanese told us that we’d be taken to a beautiful vacation place where we would spend the duration of the war in pleasant surroundings. They put us in an old English freighter, and in a few days we were tied up in Singapore.

EN: Eventually you were shipped to Burma [January 1943] to begin work as slave laborers on the “Railway of Death.”

HB: We learned that we were to build a railway from Moulmein down to near Bangkok. We were put in a camp that had a boundary marked with a string attached to small sticks. There were strict orders not to go beyond that boundary. One evening some of us were standing near the boundary, and a guard accused us of trying to escape. Our punishment was to kneel with a three-inch-diameter piece of bamboo behind the knees. Soon your legs became numb and you could tolerate it better. I don’t remember how long they had us stay there, but when they let us go, we could not walk. We were also slapped many times—the officers did that to their own soldiers, too.

“It was shameful to all POWs, and glamorized by Hollywood to make money.”

EN: The Death Railway was done almost completely by hand under primitive and horrific conditions.

HB: It was very brutal work. Our first work was digging dirt and piling it on the railroad bed. A bamboo pole would be put through the loops of a burlap bag, a POW on each end of the pole. We’d walk to the digging area and lower the bag, where a digging guy would shovel soil into it. We’d then walk over to the railroad area and dump it. There was always a long line of POWs constantly filling the bags and dumping the dirt. Ants had nothing over us.

EN: What was the next step?

HB: After a section of railroad was filled to its proper level, the next step would be to add a surface of crushed stone. They would find outcroppings of stone as near as possible to the railroad, then use dynamite to loosen it. We would sit with a small hammer and break up the stone into smaller pieces, about the size of an egg, then carry it over to the leveled fill.

EN: What were the next steps in construction?

HB: A POW crew would lay ties down on the stone. These ties would have to be carried one by one, and they were not light. Many times we saw that the ties were made of beautiful teak or mahogany. The steel rails were next. The first ones were carried in a railroad flatcar. Later on, as we continued building, there was what looked like a truck, but had railroad wheels instead of tires, and it would push the rail flatcar along the newly completed sections of railroad.

EN: The terrain and climate must have been horrible, especially for abused, ill-fed men not used to the tropics.

HB: The construction process sounds simple, maybe easy, but there were many hills and valleys, and many of the hills contained solid stone that had to be dynamited and dug. This meant long, dreary, hard work days. To make holes for a Japanese engineer to put dynamite in, one POW would hold a long chisel and another would pound it with a 10-pound sledgehammer. During this process, little flakes of stone would fly around and, if it hit you, the wound would be the beginning of a tropical ulcer. Such ulcers were the cause of many lives lost.

EN: The famous 1957 film The Bridge on the River Kwai makes railroad construction a paradise by comparison. What do you think of the David Lean movie?

HB: It was shameful to all POWs, and glamorized by Hollywood to make money. I’ve talked with Aussie and Brit POWs, and they of course agree wholeheartedly. The Japanese government has had an ironclad position on their treatment of POWs, downplaying the barbarity, and I don’t think they will ever change. PBS has aired, and continues to air, a documentary on the Death Railroad that features an elderly Japanese who was an army engineer who worked on the building of the road. In the film he denies any harsh treatment of POWs. [Brooks was also featured in the documentary.]

EN: How long did you work on the railroad?

HB: Two and a half years. The food was absolutely terrible. That’s one of the reasons why so many of us died. The only time you’d see the food was at the midday meal. The other times it was too dark. We would eat in the morning, before it was daylight, midday, and then after sunset. At midday we’d get rice and “stew,” but the stew was mostly water and a few vegetables. Sometimes there were maggots in the stew, but if you couldn’t see them, you ate them.

EN: You had little or no medicine, and “hospitals” were really dumping places where the Japanese placed men too sick to work. It was a place to die.

HB: The worst thing about the experience was to see shipmates die of starvation. When one of us got sick, or was so malnourished they couldn’t walk, we knew it was the end. And if you got a tropical ulcer, it would just eat you away.

“’Are you ready to go home in the morning?’”

EN: How were you liberated?

HB: Near the end of 1944, I was taken with a group of about one hundred men and sent to Saigon, then part of French Indo-China. On August 15, 1945, a Japanese officer came and gave a speech that the war was over and that we’d go home. But we found out from some French residents about the A-bomb and what really ended the war. Then we saw three big four-engine American planes flying over Saigon. We later learned they were C-47s.

EN: It was then you realized liberation was at hand.

HB: A jeep came into camp, and in it were two American Army officers. “Are you ready to go home in the morning?” they said. They gave us candy and cigarettes, and then had us parade by the jeep and give them our name, service rank or rate, and our home address and telephone number. I don’t think many of the guys got to sleep at all that night.

EN: The next morning you were driven to an airfield, where C-47s were waiting.

HB: Those pilots looked not a day older than 19 or 20, but what a sight for our poor eyes! Needless to say, many of us were shedding a few tears. It just seemed too good to be true. We stopped in Bangkok and Rangoon for fuel. Late in the pm we landed in India, where we were trucked to the Forty-Second Army Hospital, Calcutta. We were all given new clothes, and in the dining room we all wanted to take pictures of the food. Some guys did.

EN: What happened next?

HB: That night we slept on snow-white sheets, and the next day we were given a quickie medical exam. After about two weeks we were off for home in a C-54. We stayed overnight at Cairo, Egypt, and at Casablanca, and also stayed at a base in Newfoundland before arriving in the United States. We did get to call our homes soon after arrival from Calcutta.

EN: It must have been quite a homecoming.

HB: I shall never forget meeting my parents, brothers, and sisters, and also our neighbors.

EN: Besides the obvious trauma, how did your experiences as a POW affect your life?

HB: You have a greater appreciation for the simpler things in life. You don’t have to be rich to be happy and satisfied.

My dad came home from the death camps after the sinking of the Houston, after the war.I was named after a man that was executed by the Japanese for trying to escape. Maybe Harold Brooks, don’t know never was told . Been researching as much as possible. Saw he was MIA and declared dead after the war. From what I’ve researched it’s a miracle any of you came home. May God bless all who have served.

My wife and I went to the real Kwai bridge three years ago. There is a ramshakle “museum” there with a few items and some some fading descriptions but a poor memorial to the men who died working on the railroad. There were quite a few tourists and it would certainly be worthwhile for the government to invest a little money in restoring the place.