By Al Hemingway

When the United States was plunged into World War II on December 7, 1941, more than 16 million Americans answered their country’s call and donned a uniform. Of that number, approximately 12 million would serve overseas for an average of 16 months. Nearly four years later, almost 300,000 would be dead or missing and another 671,000 wounded in action.

They fought on beachheads, went house-to-house, waded through unforgiving jungle streams, flew threw murderous enemy antiaircraft fire, and braved the incessant attacks of the dreaded Japanese kamikazes, to finally defeat a determined foe. Most did not see their homes and families for years, but they had a strong sense of duty that pushed them onward. It was their numerous sacrifices that saved the world from fanatical despots bent on global domination.

Most World War II veterans today are in their mid-80s. Unfortunately, they are dying at a rate of approximately 1,100 a day nationwide. Although many consider World War II the defining event in world history, it took U.S. veterans nearly six decades to have a memorial that they could call their own.

On that dedication day in May 2004, President George H.W. Bush said, “These were the modest sons of a peaceful country, and millions of us are very proud to call them ‘Dad.’ They gave the best years of their lives to the greatest mission their country ever accepted. They faced the most extreme danger, which took some and spared others for reasons only known to God. And wherever they advanced or touched ground, they are remembered for their goodness and their decency.”

On that dedication day in May 2004, President George H.W. Bush said, “These were the modest sons of a peaceful country, and millions of us are very proud to call them ‘Dad.’ They gave the best years of their lives to the greatest mission their country ever accepted. They faced the most extreme danger, which took some and spared others for reasons only known to God. And wherever they advanced or touched ground, they are remembered for their goodness and their decency.”

The images below were taken by Los Angeles-based photographer Thomas Sanders. He is committed to photographing as many veterans as possible until his ultimate goal of compiling a book of his work can be accomplished. “I would love to travel the United States, and the world for that matter, to photograph these men and women,” he said. “I think it would be wonderful to publish a book and have an image of an American veteran on one page and the image of a veteran of another country on the next.” See more of Tom’s veteran photos at www.tomsandersphoto.com.

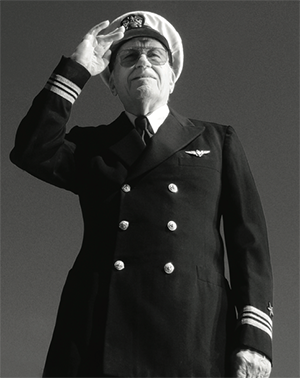

Lt. Commander Ted Reinhardt, U.S. Navy (Ret.)

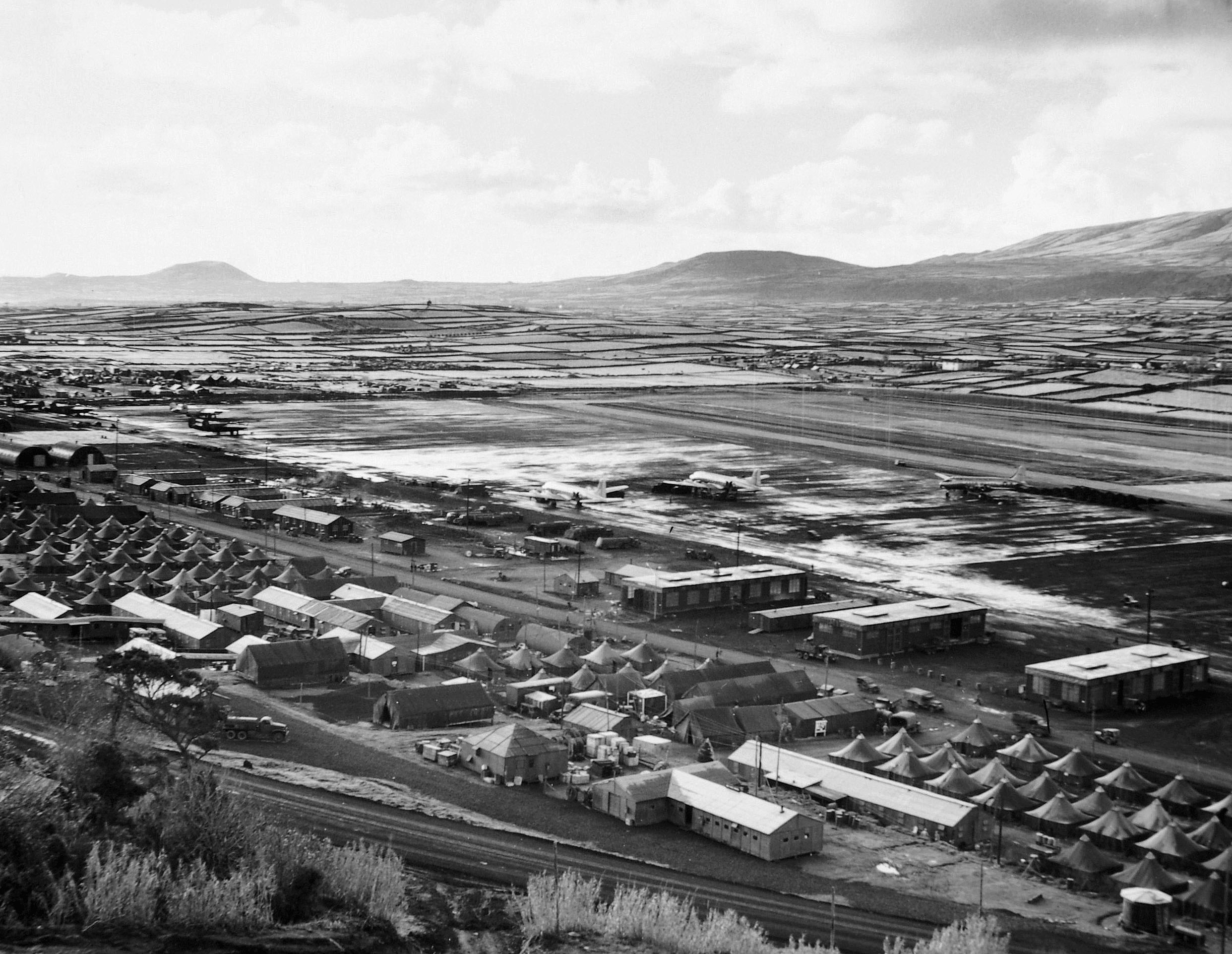

The naval air station (NAS) at Corpus Christi, Texas, was built in 1938 to train naval aviators to meet the increasing demand. By the start of the war, 800 instructors were training an average of 300 cadets per month. In June 1943, former President George H.W. Bush was the youngest pilot ever to graduate from the school. By war’s end, more than 35,000 cadets had graduated from the air station. According to their website: “Corpus Christi was the only primary, basic and advanced training facility in existence in the United States. At one time it was the largest pilot training facility in the world.”

The naval air station (NAS) at Corpus Christi, Texas, was built in 1938 to train naval aviators to meet the increasing demand. By the start of the war, 800 instructors were training an average of 300 cadets per month. In June 1943, former President George H.W. Bush was the youngest pilot ever to graduate from the school. By war’s end, more than 35,000 cadets had graduated from the air station. According to their website: “Corpus Christi was the only primary, basic and advanced training facility in existence in the United States. At one time it was the largest pilot training facility in the world.”

Ted Reinhardt was an instrument instructor with 12 Dog Training Squadron during the war.

“I also taught primary and advanced training at that time,” he said. “I met my wife Em there, and we were married in a military wedding. I was supposed to receive orders to the fleet, but they were cancelled when the war ended. I stayed in the naval reserve and retired in 1972.”

Pfc. Sam Simon, U.S. Army

There isn’t a more illustrious division in the United States Army than the famed 42nd Infantry Division. Nicknamed the “Rainbow” Division because of its distinctive shoulder patch, the unit fought in both world wars serving in the European Theater.

There isn’t a more illustrious division in the United States Army than the famed 42nd Infantry Division. Nicknamed the “Rainbow” Division because of its distinctive shoulder patch, the unit fought in both world wars serving in the European Theater.

Sam Simon was assigned to Company H, 2nd Battalion, 242nd Regiment of the division.

He landed in Marseilles, France, in December 1944, and was immediately sent to Strasbourg in the Alsace region. Simon’s regiment successfully defended a 31-mile line to prevent the Germans from breaching their perimeter. Given the codename “Task Force Linden,” after their assistant division commander Brig. Gen. Henning Linden, Simon’s unit repelled savage German counterattacks and by late January 1945 went on the offensive.

By mid-February 1945, the 42nd Division had pushed through the Hardt Mountains and breached the Siegfried Line. From March 15-31, the unit had seized Dahn and Busenberg, crossed the Rhine River, and taken the historic town of Wertheim am Main. From April 9-19, Simon was engaged in house-to-house fighting with fanatical troops from the SS as his company advanced, capturing the industrial towns of Schweinfurt and Furth.

On April 25, 1945, Simon was involved in heavy fighting in the town of Donauworth, Germany. “I was assigned to a heavy weapons section as a machine gunner,” he recalled. “The major wanted us to have our guns pointed in a certain direction. We fired all our ammunition, and I ran back to get more. Mortars started landing in a field about a quarter mile in front of us. The next batch landed right in the middle of us. The sergeant in front of me was killed, as was the guy behind me. I caught some steel in my throat and left knee.”

The war was over for Simon. He was sent to a hospital for a long recovery. He was awarded a Bronze Star with “V” device and a Purple Heart medal. To this day, he is intensely proud of being a member of the 42nd “Rainbow” Division.

1st Lieutenant Robert Covey, U.S. Army Air Corps

Arriving in the Pacific Theater in 1944, Robert Covey was a pilot with the 90th Bomber Squadron, 3rd Attack Group. His plane, the Douglas A-20 Bomber, called the Havoc, was the most manufactured attack bomber of the war.

“It was very dependable,” remarked Covey. “It was a twin-engine, mid-wing bomber that could carry a large bomb load and napalm.”

When the Allies invaded the Philippines to liberate the islands from the Japanese, Covey’s unit was right there flying air support missions. From Leyte, Luzon, and Mindoro, the 90th Squadron led the way in the Pacific Theater by participating in 10 campaigns.

“We flew a lot of ground support in the Philippines,” remembered Covey. “We dropped smoke to mark locations but it was really hard to see in that dense jungle. I came back to the airfield with a few holes in my aircraft at times.”

After the war, Covey continued with his love of aviation by becoming a flight instructor. When he retired, they gave him an old prop from a plane that he proudly displayed over his fireplace.

“I sold the house, so it stands in a corner now,” he said. “I’ll probably give it to one of my grandkids. When that picture was taken, I held the prop looking skyward.”

1st Lieutenant Harley Beam, U.S. Army Air Corps

Harley Beam is a very lucky man. As the pilot of a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bomber, Beam flew 28 combat missions without a scratch, quite a feat when one considers that more than 10,000 of the aircraft were lost in the European Theater.

Harley Beam is a very lucky man. As the pilot of a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bomber, Beam flew 28 combat missions without a scratch, quite a feat when one considers that more than 10,000 of the aircraft were lost in the European Theater.

Assigned to the 570th Bombardment Squadron, 390th Bombardment Group, he joined the unit in Framlingham, England, in May 1943. The group compiled quite an illustrious record during the conflict. On August 17, 1943, they bombed the Messerschmitt plant in Regensburg, Germany, and were awarded a Distinguished Service Citation for their efforts. A Presidential Unit Citation was presented to the group for striking the antifriction bearing plants at Schweinfurt, Germany, while dodging German fighter planes. “I flew bombing missions over France, Denmark, Holland, Austria, and Germany,” said Beam. “The B-17 was a good plane. It was reliable and durable. I was lucky. I never got wounded.”

At war’s completion, the 390th Bombardment Group had flown over 300 missions and released 19,000 tons of ordnance over enemy targets. They had 377 confirmed kills, 57 probables, and 77 damaged enemy aircraft.

But the cost in war is always high. The unit lost 181 planes with 714 crewmembers killed. Harley Beam was indeed fortunate.

Ensign Em Reinhardt, U.S. Navy

“I always wanted to be a registered nurse,” confessed Em Reinhardt. “So right after I graduated from my class I was commissioned in the U.S. Navy. They were so eager to get nurses, and we didn’t have much training in protocol. There was not much saluting going on. When a sailor saluted me I just laughed!”

“I always wanted to be a registered nurse,” confessed Em Reinhardt. “So right after I graduated from my class I was commissioned in the U.S. Navy. They were so eager to get nurses, and we didn’t have much training in protocol. There was not much saluting going on. When a sailor saluted me I just laughed!”

Reinhardt went to St. Louis, Missouri, for nurse’s training and then was assigned to the naval hospital at the Great Lakes Training Center in Benton, Illinois. From there, she was sent to the naval air station (NAS) at Corpus Christi, Texas, to work with psychiatric patients.

“What a change from Great Lakes,” exclaimed Reinhardt. “One minute the wind is howling and you’re freezing and the next the temperature is over 100 degrees.”

While stationed at Corpus Christi, Em met her future husband, and they were engaged. They had a military wedding because her spouse had received orders to go overseas.

“It was quite an affair,” she laughed. “We had a military wedding, and the head psychiatrist gave me away. Most of the reception was attended by the nurses, pilots, and patients. They made quite a punch—there were no ration cards for punch—but there was a lot of booze in it.”

The newlyweds only had two days for a honeymoon. Their first night was actually spent apart—he in the bachelor officers’ quarters— and she in the nurses’ quarters.

“I can’t wear my uniform anymore after three children,” she said. “But I enjoyed it. We had a good life.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments