By John Wukovits

The haggard American sailors aboard the limping cruiser hoped that the journey upon which they had just embarked was the long-expected voyage back to the United States. After all, the USS Houston, flagship of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, had been stationed in the Far East for 17 straight months without respite. The vessel sorely needed repairing, while the men wondered how much longer they could effectively function without rest.

The battered ship and crew suffered not so much because of the extended sea duty, but because of when and where they were, late 1941 and early 1942 in the Southwest Pacific, where the Japanese directed some of their fiercest opening blows of the war. Consequently the ship and crew had seen some of the heaviest sea action of the strife.

Four times in less than three months, the Houston had been reported sunk. Japanese bombers struck her on the war’s opening day, December 8 (December 7 in Pearl Harbor, east of the International Date Line). On February 3, 1942, a total of 49 Japanese bombers plunged from the skies and bracketed the ship with bomb explosions that killed 48 men and wounded another 25. Although the Japanese departed with the assumption that they had mortally wounded the damaged ship, the Houston survived the ordeal.

Twelve days later, as the Houston escorted a convoy of four troop ships from Australia northwest to the island of Timor, 50 enemy aircraft pounded the Allied force. The American cruiser saved the four transports by circling away and drawing off the Japanese aircraft, and while she absorbed more blows from the enemy, the Houston once again survived.

Those actions served as preludes to the ship’s main ordeal: The February 27, 1942, Battle of the Java Sea. In a knock-down, no-holds-barred affair reminiscent of sea battles of old, Allied and Japanese ships stood toe-to-toe and fired at each other in a momentous battle. When the smoke cleared, 13 Allied vessels rested on the ocean’s floor, while the badly damaged Houston and the accompanying Australian cruiser Perth limped to the island of Java.

The American ship resembled a junkyard. Twisted guns nestled amid torn metallic sheets and mangled bodies. Books, personal effects, and wall fixtures lay in heaps on the floors of cabins, and water leaked from fissures in the ship’s plates caused by bomb concussions. However, those men who survived took solace that the ship had again withstood a furious enemy assault. Maybe the cruiser, already labeled “The Galloping Ghost of the Java Coast,” was meant to live to reach California.

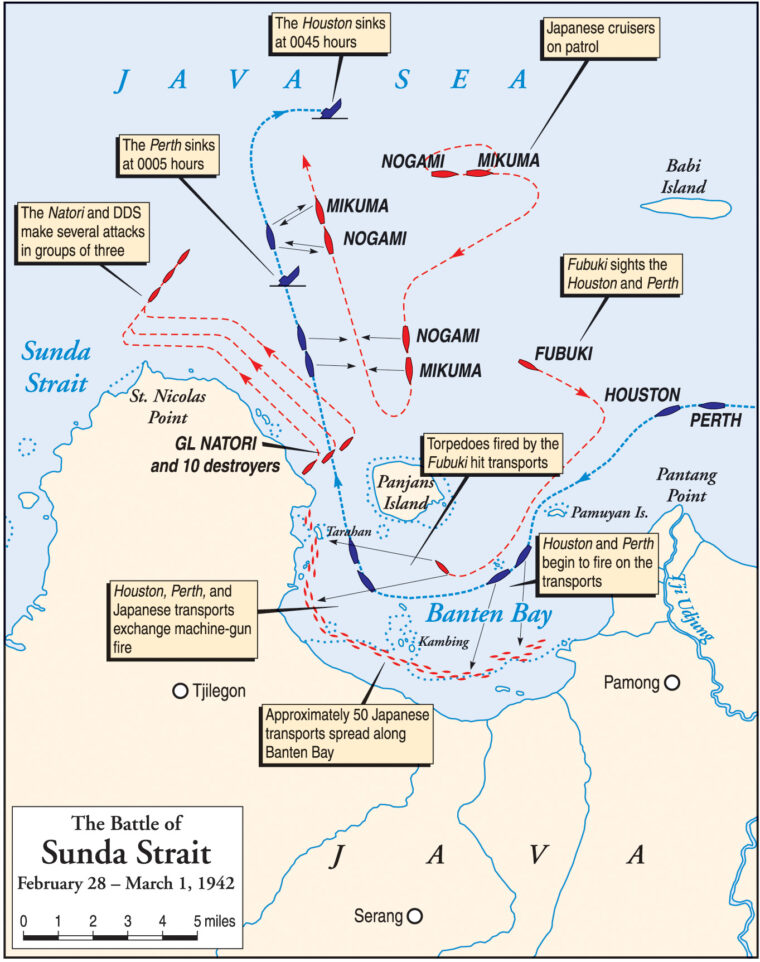

First, she had to safely exit the Java area, no small task in itself. Most of the Allied naval power had been eliminated in the Battle of the Java Sea, and Japanese ships were sure to be prowling the waters searching for any stragglers. The best hope for the Houston and Perth was to flee west to the end of Java, swerve south through the Sunda Strait, and burst into the Indian Ocean. Once there, the ships could set course for Australia and temporary safety. But questions nagged at everyone from the ship’s captain to the lowest seaman. Would the pair be able to avoid detection from an enemy intent on destroying them? Could they elude an enemy net being quickly drawn around the area?

The officer in charge of the American destroyers in the region, Commander T.H. Binford, doubted that enough time remained to salvage the few remnants of the Asiatic Fleet. On February 28 he informed his superior, Rear Adm. William A. Glassford, “The bottom’s dropped out. I want to get out of here and go to Australia. If we stay 24 hours, it will probably be too late to escape.”

At least the crew of the Houston, which was commanded by Captain Albert H. Rooks, had the comfort of knowing another ship would accompany them in the dangerous dash through Sunda Strait. The Australian cruiser Perth also benefited from the bold leadership of a man universally admired among the crew, Captain Hector Waller, a stocky, broad-shouldered man who issued orders crisply, fairly, and calmly. Nicknamed “Hardover Hec” and “The Fighting Fool” for his penchant in battle of maneuvering his large ship as if it were a smaller boat and charging directly at the foe, Waller treated everyone with respect and considered his crew his main responsibility.

As a result, the men placed their ultimate trust and faith in Waller. When he announced to them on February 28 that, after only a few moments in the port of Batavia to evacuate some troops, they would again head to sea, they believed they would emerge unharmed. Waller informed them that the possibility of action remained but that Dutch air reconnaissance reported Sunda Strait clear of enemy ships. Their faith faltered somewhat when the ship’s mascot, a cat named Red Lead, three times attempted to leave the ship when it docked at Batavia, actions considered bad omens, but Waller had pulled them through difficult times before and they believed the plucky captain could do it again.

They might not have felt so secure had they known what actually prowled the waters in their vicinity. Two immense Japanese invasion forces were headed toward Java, bristling with warships. While one force swerved toward the eastern edge of Java, Rear Adm. Takeo Kurita led the Western Attack Force toward Java’s west end, directly where the Houston and Perth hoped to exit. Kurita commanded four heavy cruisers and the aircraft carrier Ryujo, supported by another three cruisers and a destroyer squadron if needed. Once they left Batavia, Captain Waller and Captain Rooks would be headed directly into an overwhelming Japanese force.

Maybe Lt. Cmdr. Walter G. Winslow caught wind of something. An aviator aboard the Houston, Winslow looked at the beautiful wooden head he had purchased in Java six weeks earlier that rested on his desk in his room. He had nicknamed the figure Gus and had found the carving kept him company in those weary, solitary moments he spent in the cabin. Realizing the predicament they might now be in, Winslow stared at the wooden head and said aloud, “We’ll get through, won’t we, Gus?”

Gus had no reply, but the Japanese did. The two Allied ships quietly departed Java near sundown on February 28, 1942, and immediately set course to the west, still hoping to avoid enemy detection. That possibility dissolved when, around 10:50 pm, the Japanese destroyer Fubuki spotted the cruisers as they neared Bantam Bay to the west of Batavia. For a time the destroyer shadowed the unsuspecting ships as they steamed along Java’s northern coast, then closed on Bantam Bay and a collection of Japanese troop transports that lay temptingly offshore. The Allied commanders hoped to sneak in, create havoc among the transports, and still dash to Sunda Strait a short distance to the west. Unfortunately, as the ships swerved into the bay, the Allies spotted the Fubuki.

Waller at first thought the ship might be an American destroyer, but that illusion lasted only moments before he realized what specter charged toward him. “Jap destroyer. Sound the rattles. Forward turrets open fire,” ordered the veteran commander. Almost before the words had issued from his mouth, more Japanese ships were spotted converging on the two cruisers. Nine enemy destroyers and three cruisers rushed to trap the outnumbered vessels before they could burst out of the bay.

While the Japanese cruisers lurked at a distance, from where their powerful shells could do more harm while giving the Allied ships smaller targets at which to aim, the nine destroyers raced in and unleashed the first group of 87 torpedoes launched at the Houston and Perth. Rooks and Waller executed an intricate circle to avoid the flurry of enemy torpedoes, then headed west on a course paralleling the Japanese troop transports near the shores of Bantam Bay. Every missile in the initial batch missed its mark, although some continued on to smash into the surprised Japanese soldiers aboard the troop transports.

The Allied cruisers answered with everything they had, including the 6-inch guns on Perth, which erupted with such force that some of the Australian sailors near them were knocked to the deck. Main batteries boomed as they hurled their large projectiles, while smaller guns emitted sharp cracks or rhythmic rat-a-tat-tats. Noise, smoke, and confusion swallowed every man on both decks.

Aboard the Houston, Lt. Cmdr. Winslow jumped out of his bed and headed toward the bridge. As he made his way, Winslow stopped for a brief moment to witness the awesome spectacle that lit the nighttime skies as Allied guns put up a game answer to the hundreds of Japanese guns that shot at them. He watched the “fiery streaks of tracers hustling out into the night. How beautiful, I thought, these emissaries of death.”

Thinking that their only hope lay in reaching the open sea and its passage to Sunda Strait, Rooks and Waller altered course to the west to charge out of the bay, but this move only placed them in a more perilous predicament. By now two aircraft carriers, four cruisers, 13 destroyers, and a flotilla of torpedo boats waited for the trapped vessels.

So many enemy ships converged on the fleeing cruisers that the Allied ships could not possibly hope to fend them all off. Torpedo boats crept within 500 yards, while cruisers and an aircraft carrier worked from as far away as 12,000 yards. Three or four Japanese destroyers, working as a unit, would dash in as close as possible, fire their guns and launch their torpedoes, then scurry away.

The men aboard the Houston and Perth felt like farmers who had accidentally knocked over a beehive. While they swatted in one direction, more opponents streaked in from another. All they could do was pick a target—that was the easy part—and try to mount some sort of defense. Once the enemy found the correct range, the beleaguered ships would have little time to live.

Someone aboard the Perth yelled, “There are four [torpedoes] to starboard.” Another crewman hastily added, “There are five on our portside.” Finally, another man shouted, “By God, they’re all around us.”

N.E. “Tiger” Lyons on the Perth plotted at least 13 enemy ships closing on the two Allied cruisers. Ships darted so close that American, Australian, and Japanese gunners practically fired down one another’s throats. A turret captain on the Perth yelled to his gunners, “You can pick your own target. There are hundreds of the bastards.”

John Woods, a member of the Perth’s crew, momentarily halted his fighting to mutter a quiet prayer. “Look after the family at home, God, and try to look after me if you can.”

While the two Allied ships fired back, the Japanese illuminated the area with searchlights. Although the maneuver supposedly aided their gunners in spotting the quarry, it also handed the Allied cruisers a chance to get in a few licks of their own. Even that assistance, though, helped little, since two vessels firing from a limited ammunition supply could pose no effective answer against a superior foe bristling with armament.

Men aboard the Perth must have felt they stood on a floating bull’s-eye. Captain Waller muttered to Paymaster Lt. Cmdr. P.O.L. “Polo” Owens that he would rather endure “1,000 bombing attacks than to stand one enemy shelling” like this. Opposition came from so many different directions that gun crews on the Perth could do little but fire at the nearest enemy target and hope they did some good. When crews ran out of ammunition, they lobbed practice bricks loaded with extra cordite.

Japanese shells and torpedoes inflicted hideous damage aboard the Australian cruiser. A short distance from crew member William Davis, a gunner slipped a shell into his gun’s breech as a bright flash lit up the area. When a stunned Davis shook his brief stupor and again glanced toward the location of the gun crew, nothing remained. The entire crew, gun and all, had vanished in the explosion.

A torpedo plunged into the Perth’s starboard side forward engine room with such impact that it lifted the ship out of the water. Below decks N.E. “Tiger” Lyons lurched upward with the vessel, and while suspended wondered how long it would take for his ship to smash back into the sea. Hundreds of ship identification photographs crashed around Lyons, and when a fellow crew member asked if he thought they would make it out alive, Lyons shook his head no.

Three men stood on a grate above the engine room when a torpedo hit. Searing heat instantly engulfed the area, melted the metal grate, and sent the three to fiery deaths in the engine room below. Water that gushed in through the cracked hull merged with the incredible heat and boiled to death the few men still in the engine room.

The Perth, hemmed in on three sides by Japanese warships and subject to a horrific fire, absorbed blow after blow, finally forcing Captain Waller to issue the abandon ship order. One man struggled with a 4-inch shell when he heard the command and, acting instinctively, leaped overboard still clutching the shell. Some men below decks carefully walked around and replaced items in their appropriate cabinets before heading for deck.

Torpedo crewman Ian Smith’s actions undoubtedly saved lives. Smith delayed his departure from the sinking ship to check the Perth’s depth charges. He carefully pulled out the primer to each one to ensure the charges did not detonate as the ship descended to the depths. Had that occurred, some of the men in the water would have been killed from the ferocious shock waves.

Below decks, Lt. F.O. Gillan and three other men from the boiler room scrambled to reach the main deck and jump overboard before rushing water trapped them inside. With the ship settling on its side, corridors that normally could lead them to freedom now might direct them to a more precarious position or even impede their path, so the four had to exercise extreme caution in moving about.

During their frantic journey in the dark, the group came to a cross alleyway which, because of the Perth’s list, now blocked their way. If they were to have any hope of leaving the ship, the men had to leap across a 5-foot-wide abyss to the other side of the alleyway, a tricky maneuver. The first man slipped as he jumped and fell screaming into the pit, but the other three successfully landed on the other side and hastened onward.

Gillan’s two companions safely squeezed through a manhole to the deck, but before Gillan exited the ship’s bowels the Perth turned almost completely upside down and trapped the sailor under a torrent of water. The coolheaded sailor figured he had one chance to make it out alive. If he struggled to reach the surface, he would more quickly expend the air in his lungs. He also could be entangled in floating ropes or be smacked into heavy objects swirling about in the water. Instead, Gillan decided that as the ship headed downward, the rush of water leaving the doomed vessel might take him to the surface, so he lay still and trusted that the ocean would save him.

In less than one minute Gillan burst through 2 inches of oil to the surface, gasping for air as the rest of the ship’s debris bobbed about him. As he tried to regain some strength for the ordeal yet to come, he turned to watch the Perth’s propeller blades, hardly more than 30 yards distant, slip under the water. Gillan, grateful to be alive after such a harrowing trek, looked to the sky and whispered, “I’m the last man out of that ship alive. God, I thank you.”

A torpedo blast tossed Seaman H.K. Gosden in the air above the Perth and over the side. When he opened his eyes, blackness enveloped the sailor. Suddenly, he later recalled, he saw his mother crying as she opened the telegram informing her of her son’s death. The underwater imagery hit Gosden with such clarity that he even saw the words on the telegram bearing news of his death. That specter so energized him that he drew upon extra resources and finally struggled to the surface, short of air and gasping badly, but alive.

“Polo” Owens frantically tried to untie the ropes securing life rafts, but the knots proved too difficult for him to loosen. Knowing he had only moments to safely leave the dying ship, he ran to the rail, looked toward the water, and jumped before realizing he had forgotten to inflate his life jacket. After a failed attempt to blow air through the valve, Owens discarded the life jacket, removed his shirt and shorts to be more buoyant, and swam farther from the ship.

Finally, at around 12:25 am on March 1, the battered cruiser sank off Java’s northwestern edge, just as she neared the entrance to Sunda Strait. Men and debris floated in the water, their temporary home now that their ship had gone.

Now that the Perth had disappeared, the men aboard the Houston knew they would become the center of attention for every enemy gun, especially the deadly weapons aboard the cruiser Mikuma. The American cruiser had already taken on water and listed to starboard from previous hits, but what greeted her now made the initial moments of the battle appear like a cakewalk.

In the darkness, Japanese gunners had difficulty distinguishing ship from ship and had to take extra care not to target one of their own vessels. On the other hand, Houston’s gunners could fire at will, since everything around them was the enemy. At one instant during the battle, American sailors witnessed two Japanese ships unknowingly blast salvo after salvo at each other, and Houston’s gunners registered hits on three destroyers and sank one minesweeper.

At 12:15 am a salvo smashed into the after engine room, instantly scalding to death the men on duty there. Other shells blasted huge holes in the sides and deck, releasing searing steam that engulfed some sailors and threatened men at their battle stations. A torpedo plowed into the forward portion of the ship, wiping out an entire group of seamen at their posts. The stricken vessel slowed in the water from the succession of blows and from the subsequent loss of steam.

For 10 more minutes, the Houston absorbed hits from the enemy. Around 12:20 a Japanese shell destroyed the No. 2 turret, igniting the powder bags and creating a fiery beacon at which the enemy could aim. Japanese gunners wasted little time zeroing in on the range and pouring rounds into the helpless cruiser. Japanese cruisers increased their firing from a distance, while destroyers boldly moved closer to stage deadly torpedo and machine-gun attacks. The American cruiser faced such overwhelming opposition that an Army observer posted to the Houston recalled, “All communications which were still operative were hopelessly overloaded with reports of damage received, of approaching torpedoes, of new enemy attacks begun, or changes in targets engaged.”

The fires quickly spread, and when Captain Rooks feared the conflagration would reach the ammunition magazines, he ordered the magazines flooded to prevent a more serious eruption. This move briefly saved the ship, but it also drastically reduced the amount of ammunition the ship could expend toward the enemy. Limping along in the water at reduced speed and unable to maintain an effective response, the Houston sat like a dying animal surrounded by hungry vultures.

The Japanese sensed their quarry’s predicament and moved in to administer the final blows. As a flurry of shells, bombs, and torpedoes smacked into the Houston, Lt. Cmdr. Winslow thought the ship reminded him of a groggy boxer, harmed yet proud, trying to fend off the punches he knew would end the struggle.

A huge explosion from either a torpedo or a shell knocked Chief Boatswain’s Mate Otto C. Schwarz of the Houston unconscious. “When I came to, I was the only one left out of the 13 in my battery,” he recalled after the war. “I have no idea what happened to the rest. I’ve never seen them again.”

Lieutenant (j.g.) Lee Rogers, a 1938 graduate of the Naval Academy, sought cover from enemy ships that ventured close and raked the Houston from end to end. “The Japanese destroyers came alongside of us and were machine gunning the ship. They had search lights shining on us, and we would shoot out their search lights with our machine guns.”

Three more torpedoes transformed the ship’s starboard side into a landscape of twisted metal and dismembered men. Bullets from Japanese carrier aircraft ricocheted off the superstructure and pinged off sides. With dead and dying lying all over and with water pouring in below decks through gaping holes, at 12:25 Captain Rooks ordered abandon ship.

As Rooks said goodbye to some of his officers and wished them luck, a shell explosion propelled shrapnel in his direction. One piece badly mangled the captain’s chest, and within a few moments Rooks expired in the arms of another officer. The executive officer, Commander David Roberts, took charge and momentarily halted the abandonment until the ship settled lower in the water and reduced the distance men had to leap.

Ensigns Charles D. Smith and Herbert Levitt, who had been searching for wounded shipmates, came across Rooks’ Chinese cook, Tai Chi-sah, nicknamed Buddha, now clutching the captain’s body in his arms. Smith and Levitt tried to talk him into jumping overboard, but the grief-stricken Buddha gently refused. Tenderly holding the captain and swaying back and forth, Buddha said, “Captain die, Houston die, Buddha die, too.” The loyal Chinese cook went down with the ship and his captain.

The American crew continued to fire its weapons until the ammunition ran out. When the Japanese sensed their predicament, they moved in closer and raked the vessel with machine-gun fire. To avoid continued slaughter, at 12:33 Roberts reissued the abandon ship order.

The men had little time to depart the sinking ship. Already, they could hear grinding sounds emitting from below as large items shuffled from spot to spot. In an orderly procession, men filed toward the edge of the ship and plunged to the waters below. Japanese destroyers added to their miseries by spraying the decks and ropes with machine-gun fire until a handful of Americans began firing back. These few men remained at their guns while the other crew members scrambled toward the water, keeping the enemy destroyers at bay long enough for their mates to leave the ship. This unselfish act of heroism, however, doomed the unknown Americans to their deaths, as they went down with the cruiser.

Lieutenant (j.g.) H.S. Hamlin slid down the bow portion into the water because the ship listed so badly. When he reached the waterline he found, to his stunned surprise and relief, that he would not have to jump a long distance to the water—he stood on the ship’s bottom. As historian Dan Van der Vat recounted from Hamlin years later, “as I walked down the ship’s bottom toward the keel, I found myself rising out of the water to get over the bulge that the Houston’s bow had. I hit the water on the other side of that bulge and gave the best imitation of a torpedo that I could, trying to get away from suction.”

Hamlin swam as fast as he could from the ship, and when he reached a few hundred feet he turned for a final glimpse of what had been his home for such a tumultuous period. The sight almost overwhelmed him. Instead of a once-proud vessel, the ship had been transformed into a mangled, dying hulk. Hundreds of bullet and shell holes punctured the Houston’s sides and hull. The guns, previously capable of launching deadly missiles a great distance, now rested at twisted, silent angles, pointing in every direction.

“I couldn’t help think what she looked like when I first joined her, when she was the President’s [Franklin Roosevelt] yacht. She shone from end to end. I think I will always remember that last look, though. And as I watched her she just lay down to die, she just rolled over on her side and the fire went out with a big hiss.”

Winslow felt as if he were amidst a surreal setting, for illumination from the Japanese ships lighted the whole area and made everything visible in the darkness. Winslow swam away from the ship to avoid being pulled under by the suction as the Houston descended, and endured a succession of underwater shock waves produced by exploding torpedoes and shells. The waves smacked into him with such force that he felt he had been walloped by immense fists. “I shuddered to think of the havoc they inflicted on the poor souls closer to them,” he later wrote.

Winslow then halted to take a last glimpse of his ship. As the cruiser slipped underneath the water, Winslow noticed that a breeze suddenly filled the American flag, which seemed to snap defiantly as the Houston headed to her grave.

With the fighting portion of the battle now over, the men in the water faced another ordeal—survival from nature, from their fears, and from Japanese ships that crisscrossed their paths. Fuel oil floating on the surface matted in the men’s hair and clotted on their eyelids like weights. The thought of sharks and what they could do to the human body constantly hovered over them. “Tiger” Lyons, from the Perth, was paddling in the water when the concussion from a torpedo explosion caught up to him. The concussion forced a spurt of water up into his bowels and back out, making him feel as if his insides had been smashed.

Some men could not hold on for long. Lyons swam to a 44-gallon drum onto which two of his shipmates tenuously clung. When he neared the weary men, Lyons heard one of them mutter, “I’m leaving.” His companion, equally exhausted, added in a pained voice, “Oh, God.” The pair let go of the drum and vanished under the surface.

“Polo” Owen hung onto a large plank of wood with a petty officer and began wondering what drowning felt like. Near the limit of his strength, Owen decided to release his grip and drift away to a quiet death, but he was jarred back to reality by the petty officer, who pleaded with him, “For God’s sake, don’t leave me!” Owen, somewhat embarrassed, replied, “Sorry,” and hung on with a tighter grip.

The men, Americans and Australians alike, were physically and emotionally spent by their long struggle. Lieutenant Joseph Dalton of the Houston was floating in a raft with other American survivors when a Japanese landing craft started towing it to shore a half-mile away. Dalton noticed a group of Japanese officers vehemently arguing with each other, apparently over the fate of the Americans on the raft. One Japanese finally cut the raft loose, and as it drifted away another Japanese aimed his rifle at the group. Instead of ducking for cover, the weary Americans sat in the open, waiting for the burst that would take their lives. After a few moments, the Japanese soldier lowered his rifle and allowed the raft to float away.

Chief Boatswain’s Mate Otto Schwarz, along with others, spent 15 excruciating hours in the water. During that night, he heard constant screaming from men near him and the sounds of Japanese machine guns as the enemy moved from group to group, shooting the Americans and Australians as they floated in the water. “I thought, ‘Oh God, they’re machine gunning the men in the water,’” related Schwarz later.

When a Japanese torpedo boat inched toward Schwarz, he had to take quick action. “I didn’t know what to do. So I made an air pocket with the high collar of the life jacket, put my face in it and just bobbed up and down. The boat came up and I could hear them speaking Japanese on the deck of the boat. They put a search light on me, and I just kept waiting for the bullets to come.” The Japanese moved so close that Schwarz even felt a sailor poke him with a rifle to see if the floating American was dead. Expecting a flurry of bullets to terminate his life at any moment, Schwarz waited for what seemed hours but in reality was only a few seconds, until finally the Japanese craft backed away and departed.

Some distance away, a Japanese destroyer approached a group of survivors on a float, including Seaman H.K. Gosden of the Perth, and tossed down ropes in an effort to haul the weary men aboard. The bitter Australians were not about to accept aid from an enemy that had, only moments before, tried to kill them. “You know where to stick it, mug—we’d rather drown,” yelled one man. The destroyer left the men to their fates.

A short while later, as Gosden sat with his legs over the float’s side, he felt a pull at his legs. He peered toward the water to see a group of Japanese sailors and soldiers, obviously from the handful of troop transports that had been sunk, paddling toward his float in hopes of securing a spot. The enemy soldier tugging at Gosden’s legs muttered something unintelligible, but Gosden knew the man was begging for help. Instead, without saying a word, Gosden shoved his boots in the man’s face and kicked him away.

Other Japanese soldiers tried the same maneuver, but each time the Australians forced them back. “You killed my mate, you bastards, you killed my mate,” shouted one man.

Not everyone in the water reacted with anger. Commander G.S. Rentz, the gray-haired chaplain from the Houston, hung onto a raft with 12 other survivors when it began sinking under the weight of all the men. Without muttering a sound, the chunky Rentz swam away from the raft, but another sailor brought him back. Twice more Rentz attempted to leave the raft, but each time his companions halted him. Finally, the chaplain looked at his shipmates and said, “You men are young with your lives ahead of you. I’m old and have had my fun.” After uttering a brief prayer, Rentz removed his life jacket and disappeared, yielding his life so that others might endure.

Over the coming hours, groups of exhausted men, Australian, American, and Japanese, reached Java’s shoreline. Among them was the highest-ranking Japanese officer, General Hitoshi Imamura of the 16th Army, who had been aboard his headquarters ship, the transport Ryujo Maru, when a torpedo sank it.

Imamura jumped overboard and clung to driftwood for 20 minutes until he was rescued. As he bobbed on the surface, Imamura heard loud, scraping noises coming from a sinking transport. Automobiles and tanks had broken their bindings on the listing ship, scraped along the decks, and plunged into the water. Reaching shore, the drenched general slumped to the beach, exhausted from his rigors. His sour mood was not brightened when an aide rushed over and, in an effort to cheer the general, congratulated him for a successful landing.

The general’s ire would have soared had he known that he had been forced into the water by an errant Japanese torpedo instead of an American one. He never found out. When Commander Shukichi Toshikawa of the Japanese Navy was selected to apologize to Imamura for the mishap, Imamura’s aide canceled the idea. “Don’t tell General Imamura,” cautioned the aide. “He thinks the American cruiser Houston did it. Let her have the credit.”

After 18 hours in the water, Lt. (j.g.) Rogers of the Houston crawled ashore with other survivors. They carefully advanced inland toward a village, where natives placed the men in carts and took them to the village jail. The next day a squad of Japanese soldiers ended their hopes of freedom by taking them prisoner. When one of the Japanese discovered the captives came from the United States, he said, “Oh, Americans! Baseball, Babe Ruth.”

The Japanese who captured Otto Schwarz were not as kind. Since the horses intended to be used to pull carts had been lost with one of the transports, they forced the prisoners to pull their supply carts. For four days the tired men labored to move the carts along rough jungle roads. Whenever they faltered, a Japanese bayonet prodded them to further effort.

After their capture, the men from the Houston and Perth spent the remainder of the war years in a succession of dreary prison camps, where they endured the usual routine of beatings, inadequate food, and exhausting work. When war’s end arrived in 1945, only 368 men out of more than a thousand aboard the Houston, and 229 out of 682 men from the Perth, survived. The rest either perished during the battle, in the water afterward, or in prison camps.

The American military knew little of what happened to the Allied cruisers. Most U.S. naval authorities believed the Houston went down with all hands and listed the crew as missing in action. Families of the crew had to console themselves with the faint hope that their loved ones had somehow survived the mysterious encounter and would one day be reunited with them. More than three years elapsed before two crew members, after escaping from prison camp and safely reaching Allied lines, brought information of the battle.

The actions of the pair of cruisers had little effect on the outcome of the war. Their labors had not been in vain, however, for at least they had fought back. They had not been caught with their guard down or with their aircraft neatly aligned in rows, as had their American compatriots at Pearl Harbor and the Philippines. They had ultimately been sunk, but the Houston and Perth let the Japanese know that Allied opposition was much hardier than expected.

The American public reacted to the loss of the Houston with determination. The city of Houston, Tex., sponsored an emotional enlistment campaign. “Avenge the Houston!” urged a citywide slogan, which helped compel residents to build an 80-foot replica of the cruiser to attract enlistees. By Memorial Day 1942, less than three months after the battle, more than 1,400 men were sworn into the Navy in a mass induction ceremony. The Houston had departed, but her fighting spirit remained.

John Wukovits is the author of a forthcoming book on the battle for Wake Island. He has previously written Devotion To Duty, a biography of Admiral Clifton A.F. Sprague, hero of the Battle of Leyte Gulf, published by the Naval Institute Press.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments