By Eric Niderost

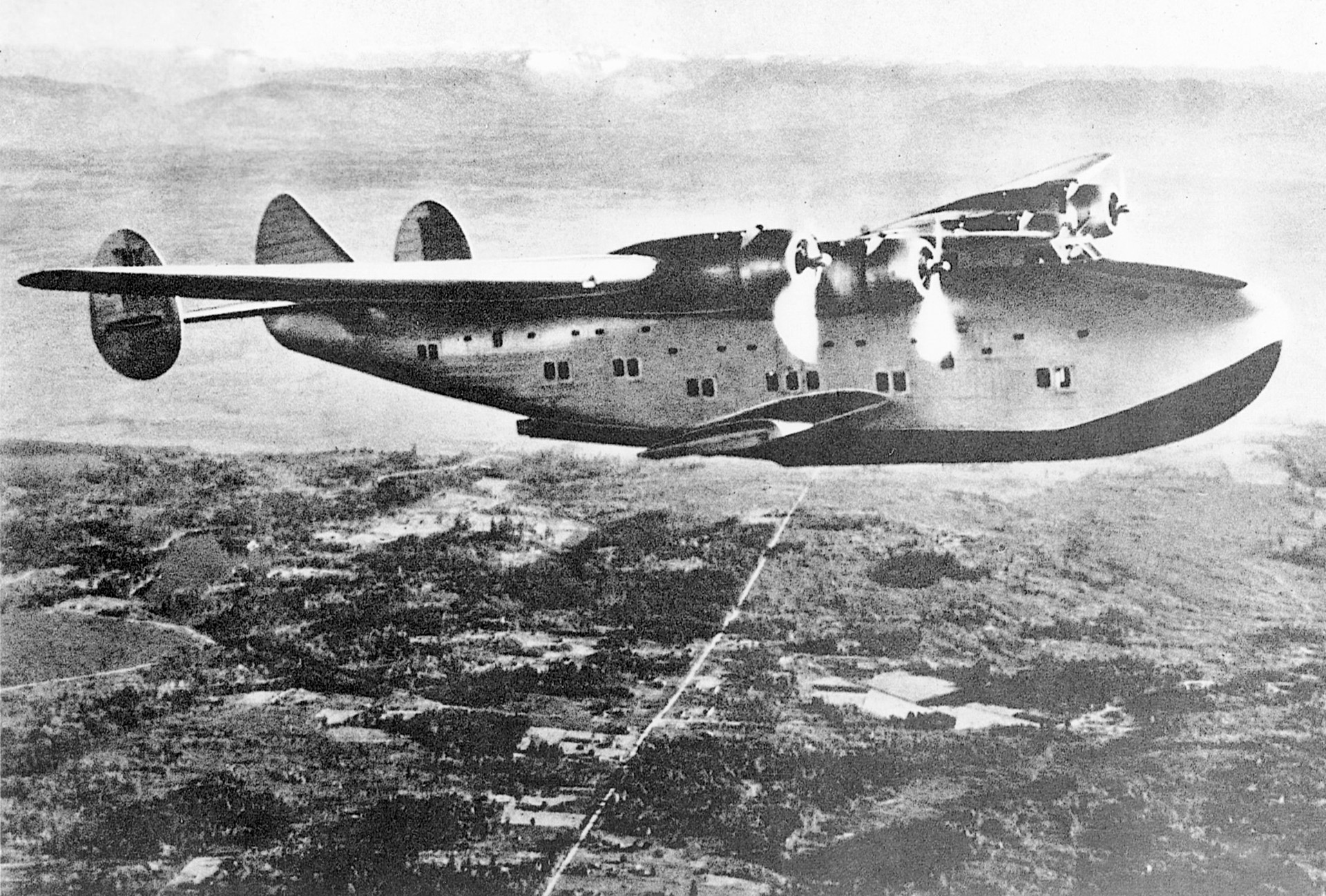

On the afternoon of January 7, 1943, Boeing 314s Dixie Clipper and Atlantic Clipper took off from the Marine Air Terminal, La Guardia Airport in New York, their destination Miami. Captain Howard Cone, Jr., was at the controls of Dixie Clipper and, as the veteran pilot eased the throttles forward, the giant seaplane began to lift its enormous bulk out of Riker’s Island Channel, long plumes of water trailing in its wake as it gained altitude. It was the beginning of what was to prove a very historic journey.

Both flying boats reached Miami safely after a 71/2-hour flight. Cone and Atlantic Clipper Captain Richard Vidal knew something was up, but they were deliberately kept in the dark for the time being. They knew the assignment was designated “SM 70,” the letters standing for “Special Mission,” but this appeared to be nothing out of the ordinary.

When war broke out in 1941, the United States had only 55 four-engine aircraft, mostly commercial airliners. But the Boeing 314 flying boats, together with the Martin M-130s, had the capacity for transporting large amounts of cargo and/or passengers across vast distances. This made them crucial for the war effort.

Pan American Airways teamed up with the U.S. military, a “marriage” of convenience that would last for the duration. It may have been a hasty union brought on by the exigencies of war, but it seemed to work well. Each of the 314s was sold to the War Department for $900,000. Then the flying boats were allotted to the Army and Navy. Although technically government aircraft, much would go on as before. Pan American would operate flight schedules and maintain the aircraft. Airplanes would be crewed by Pan American personnel, not the military.

In return for these concessions, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had originally wanted to requisition all commercial aircraft outright. Pan Am had to be ready to supply flying boats for special missions. The assignments varied. They might be used to transport vitally important cargo or to ferry “Priority One” passengers across the ocean.

Captain Cone and his nine-man Dixie Clipper crew wore tan naval reserve uniforms for the flight, abandoning their customary blue “sea captain” Pan Am garb. The stayover at Miami proved a busy one. The two flying boats were serviced and thoroughly checked, though both had earlier undergone major overhauls.

Captain Cone and Captain Vidal received secret orders during a flight briefing four days after their arrival in Florida. The itinerary was intriguing, but still unrevealing. The first leg of the journey would be to the Caribbean, namely Port of Spain, Trinidad. Belem, Brazil—a city at the mouth of the great Amazon River—would be the next hop. After that, the clippers were to proceed to Bathurst, Gambia, a British colony in northwest Africa.

After checking weather details and going over flight plans, Cole and Vidal were finally given passenger manifests. It was certainly a VIP roster, top-heavy with Navy brass such as Admiral William D. Leahy and Admiral Ross T. McIntyre. But the name “Harry Hopkins” gave the first real clue as to the importance of the mission, since Hopkins was a close adviser to President Roosevelt. Cone’s eyes were drawn to the top of the list, which mentioned a “Passenger No. One” but did not further identify the mysterious traveler. A final manifest changed “Passenger No. One” to “Mr. Jones.”

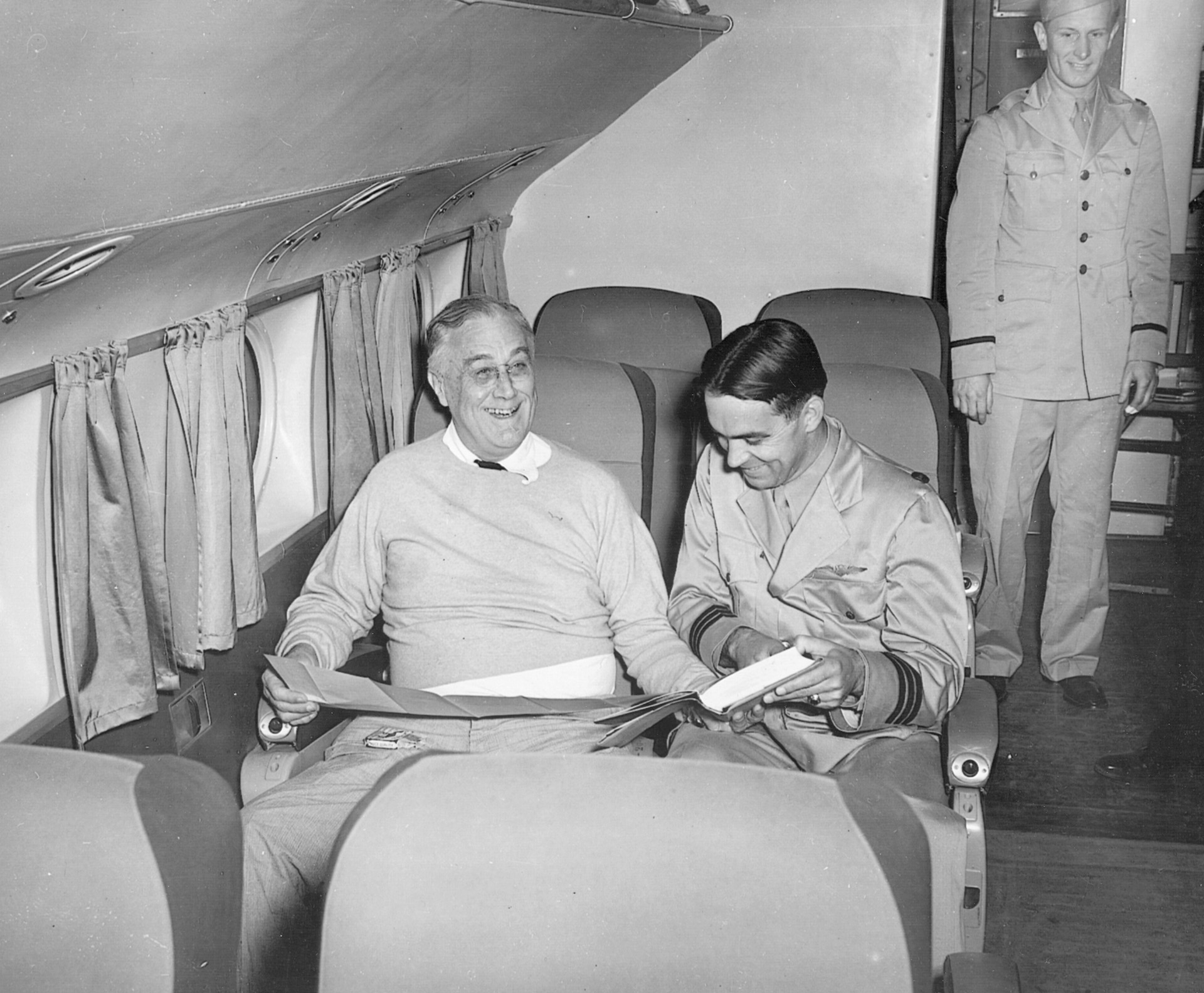

This was a transparent ploy that did not fool anyone, least of all the Pan Am veteran. Cone’s pulse must have raced faster as he grasped the heady implications: Right in the middle of a global war, Franklin Roosevelt would be the first American president in history to take an international overseas flight. While Cone reveled in his good fortune, some 2,200 pounds of luggage was being stowed aboard the two clippers. Red-tagged bags were earmarked for the Dixie Clipper, green-tagged for her sister flying boat moored nearby.

Every effort was made to ensure the comfort of the president and his entourage; nothing was overlooked. Inventory included 900 pounds of bottled water. Captain Cole carefully went over a final preflight check, then went down to Dixie Clipper’s spacious lounge to await his distinguished guest. Important journeys were usually carried out under the cloak of darkness, and this mission was no exception. During the chill predawn hours of January 11, 1943, all was in readiness for the arrival of the commander-in-chief.

President Roosevelt arrived by car, then was rolled down the dock in his wheelchair. He was then carried over the boarding ramp, and gently deposited in Dixie Clipper’s main lounge. “Mr. President, I’m glad to have you aboard, sir!” Cole declared, hand shading his brow in a smart salute. Roosevelt acknowledged the greeting with his customary charm, flashing a broad grin and extending his arm for a handshake.

When everyone was securely in their seats it was time to depart for Trinidad. Cole taxied the gigantic 314 out into Biscayne Bay, the Dixie Clipper plowing the waters into white froth as she lifted off. The Boeing 314 was the largest commercial aircraft in the world at the time, rising 28 feet out of the water and measuring 105 feet from nose to tail. To a first-time flyer it seemed impossible that the four propellers, each measuring 14 feet across, could lift the flying boat’s mammoth body into the air, but the corkscrewing props were driven by Wright double-row GR2600 Cyclone engines, powerful machines that could produce 1,600 horsepower.

As Dixie Clipper rose above Biscayne Bay, Harry Hopkins reported that the president was so excited he “acted like a 16-year-old schoolboy.” Commercial aviation was still new and wondrous, so there was little wonder why Roosevelt was so happy and excited. But why should the president undertake such a long, and despite all preparations, potentially hazardous journey?

Although it was known to few people, Roosevelt’s ultimate destination was Casablanca, in French Morocco. He was going to a high-level conference that would help determine the future course of the war. The idea for such a conference began in late 1942, after Anglo-American landings in Operation Torch had secured much of North Africa. German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps, defeated at El Alamein, was in full retreat to Tunisia. The campaign in North Africa was not over, but as British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill said, it was “the end of the beginning.”

Churchill favored a Mediterranean strategy, one that would “leapfrog” to Sicily, then establish a firm foothold on the Continent via Italy. The Americans themselves had divided councils, though they were generally united in their opposition to Churchill’s strategic vision. General George Marshall, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, favored a second front across the Channel into France, rejecting the prime minister’s notion that the Mediterranean was Europe’s “soft underbelly.” In contrast, Admiral Ernest King, chief of naval operations, wanted the bulk of American resources to be devoted to defeating the Japanese in the Pacific.

President Roosevelt wanted to iron out all these differences by arranging a top-level conference. It was deemed prudent to invite Josef Stalin, the other member of the “Big Three,” but the Soviet leader declined, citing pressing events at home. The epic Battle of Stalingrad was at its height, and though the Russians were probably going to achieve victory, Stalin did not think it was prudent to leave the country at such a time. Roosevelt understood, but felt the conference should go on, even without the Soviet leader’s presence. Churchill concurred, setting the stage for Casablanca.

Roosevelt’s daring transatlantic flight was a milestone for the American presidency, but it was not entirely without precedent. When America entered the war in 1941, Churchill went to Washington to confer with Roosevelt, sailing aboard the new battleship Duke of York. His stay included a short visit to Canada, but by mid-January it was time to go home. On January 14, 1942, the British prime minister flew from Washington to Bermuda, where the Duke of York and a destroyer escort were waiting to take him home.

Churchill traveled on a Boeing 314, which he admitted in his memoirs “made a most favorable impression on me.” The flying boats may have been stripped of some of their amenities for the sake of wartime efficiency, but they were still luxurious and unbelievably roomy. Churchill went on to say, “There is no doubt as to the comfort of these great flying boats. I had a good broad bed in the bridal suite at the stern with large windows on either side. It was a long walk, 30 or 40 feet, downhill through the various compartments to the saloon and dining room, where nothing was lacking in food or drink.”

The British prime minister visited the flight deck, then called the control deck, to have a chat with Captain Kelly Rogers. Churchill had an insatiable curiosity about this great airborne leviathan, and he asked the pilot a number of questions. Rogers divined the reason for the good-natured interrogation and offered Churchill his seat at the controls. Beaming with obvious pleasure, Churchill accepted with alacrity.

Churchill wanted to fly the airplane, so Rogers disengaged the automatic pilot, but not without a whispered aside to his copilot to step in and make corrections should the prime minister get in over his head. Such precautions, though understandable, proved unnecessary. Churchill was a quick study and actually made a couple of banked turns under Kelly’s deferential but still watchful eye. He was at the controls for about 20 minutes, smoke drifting through the flight deck from his ever-present cigar.

Once he arrived in Bermuda, Churchill, now thoroughly enamored with the flying boats, decided to fly home instead of sailing on Duke of York. His aides heard the proposal with some consternation; transatlantic flight was still so novel. Churchill felt the benefits outweighed the risks because he was anxious to return home as soon as possible. The news from the Far East was bad and worsening by the day—rapid Japanese advances in Malaysia seemed to presage disaster.

Churchill overruled any objections, and plans went ahead to continue the journey by Boeing Clipper. Captain Kelly was enthusiastic, assuring the prime minister that the approximately 3,500 miles from Bermuda to Great Britain was well within the 314’s range. The prime minister and his party departed Bermuda on January 16, 1942. Churchill outwardly radiated confidence but inwardly he was having second thoughts. He later admitted he was “rather frightened” at the prospect of a transatlantic flight, especially when he thought of the vast “ocean spaces” and the idea of not being “within a thousand miles of land.”

But Churchill being Churchill, he conquered his misgivings and forged ahead. The Boeing 314 landed safely in Plymouth, England, after a flight of 18 hours. There was an odd postscript to the flight that Churchill might have embellished for effect. When the Boeing 314 approached England, a course correction made it seem that it was coming from Brest, that is, German-occupied France. Supposedly, six Hawker Hurricane fighters were scrambled from Fighter Command to intercept the “enemy bomber,” but luckily failed to locate the target. The story is disputed, and sometimes attributed to Churchill’s flair for the dramatic.

Winston Churchill was the first Western leader to fly across the Atlantic, and certainly the first 67-year-old man to pilot a Boeing 314. In a way, he blazed a trail that his good friend and colleague Franklin Roosevelt was going to follow.

The Dixie Clipper’s departure from Florida was without incident, a good omen for the overall success of the trip. It took 40 minutes for the 314 to gain a cruising altitude of 9,000 feet. The president had breakfast, then changed into more casual attire with the help of his valet, Arthur Prettyman. Looking over some navigation charts, Roosevelt asked if the clipper could be diverted to fly over Henri Christophe’s Citadel off Haiti’s coast. Christophe had been a 19th-century Haitian dictator with Napoleonic pretensions. He built a large fortress to secure his rule, a huge pile that was the second largest masonry structure in the Western Hemisphere.

Roosevelt’s request was granted, and the Dixie Clipper flew over the fortress to give the president a unique, bird’s-eye view of the brooding battlements. After this brief diversion, it was off to Port of Spain, Trinidad, which was reached at 4:24 pm local time. Once the two clippers were safely landed and moored, Navy launches took the president and his party ashore. Roosevelt stayed at the Macqueripe Beach Hotel overnight before continuing the journey early the next morning.

Belem, Brazil, was the next stop on the itinerary. Dixie Clipper departed Trinidad at 5:57 am, crossing the equator seven hours later. A “King Neptune” ceremony initiated those crossing the equator for the first time. “Shellbacks,” veteran travelers who had already crossed that line of demarcation, welcomed the newcomers into their select fraternity. This leg of the journey was a long one, encompassing 1,227 miles from Port of Spain to Belem.

Roosevelt napped, played solitaire, and gazed out one of the Dixie Clipper’s square porthole-like windows. Far below him, the dense Amazon jungle stretched out like an emerald green carpet. What was he thinking about? The upcoming conference? Of family, or even politics at home? The whole course of American, and even world, history would be changed if Dixie Clipper went down in this impenetrable jungle.

Atlantic Clipper landed at Belem in the late afternoon, the Dixie Clipper setting down 50 minutes later. Roosevelt went ashore, to be greeted by such dignitaries as Vice Admiral Jonas Ingram, Navy commander of the South Atlantic forces, and General Robert L. Walsh, South Atlantic U.S. Army Transport Command (ATC). This stopover was brief, however. While Roosevelt visited, the two clippers were being prepared for the Atlantic crossing, the “great leap over the pond.”

The two Clippers took off from Belem at 6:30 pm for a flight estimated to be about 19 hours in duration. The presidential party dined on gourmet food served by attentive Pam Am stewards. During the night some rough weather was encountered at 7,000 feet. Fearful the turbulence might disturb the chief executive’s sleep, Captain Cone brought the ship down to 4,000 feet where the air was smoother.

The next morning Roosevelt awoke refreshed and tackled some preliminary conference work with aide Harry Hopkins. The atmosphere was more like a college fraternity than a presidential plane traveling to a diplomatic conference. Casual wear was the order of the day, and most wore pajamas, slippers, and robes until late morning. Almost as if to compensate for the lazy morning, a formal luncheon was held in the Clipper dining room that afternoon.

The African coast was sighted, and before long Dixie Clipper was circling in preparation for the final descent. Captain Cone lowered flaps and eased her in, the Dixie Clipper skimming the water with the grace of a swan landing on a millpond. It was around 4:30 pm Bathurst time, the trip taking about 18 hours. The USS Memphis, a light cruiser, was already awaiting the presidential arrival. The Memphis was going to lodge Roosevelt and his party overnight before their departure for Casablanca the next day.

Memphis skipper Captain H.Y. McCown took Roosevelt and the other VIPs for a 30-minute tour of the harbor facilities before returning to the ship. Since the president was paralyzed from the waist down, he had to be physically lifted aboard the waiting cruiser. One aide, no doubt nervous about the delicate transfer, lost his grip and dropped Roosevelt onto the deck. The president landed on his rear end but was unhurt. Roosevelt dismissed the incident, and no doubt put the mortified aide at his ease.

The presidential odyssey would continue, but without the Dixie Clipper or Atlantic Clipper. Eighteen miles from Bathurst, three Douglas C-54 aircraft waited at Tundum Field. These four-engine transports would carry the president and his entourage the rest of the way. Land planes were chosen because the route taken would be over vast stretches of the African continent. The planes took off at 9 in the morning of January 14, 1943. The route took Roosevelt past Dakar, Senegal, then inland across the dry, barren wastes of the Sahara. The C-54s passed the jagged, snow-capped peaks of the Atlas Mountains, climbing to 11,500 feet to do so, then descended to land at Casablanca’s Medouine Airport at 6:20 pm local time.

Casablanca had an air of mystery and romance, evoking images of smoky nightclubs, foreign spies, and the Foreign Legion. Medouine Airport had been the setting for the last scene in the movie Casablanca, where Humphrey Bogart had bid Ingrid Bergman a hearty “Here’s looking at you, kid” before nobly sending her off with her husband Paul Henreid. Perhaps some of the presidential party had seen the movie, which was then a current release, and contrasted the real Casablanca with the celluloid one.

Once the airplane touched down, Roosevelt was met by White House Secret Service Agent Michael Reilly and taken by car to Dar es Saada, the villa that would be his home for the next 12 days. Winston Churchill was already in Casablanca, having arrived a day earlier, and was holding court at his own “digs” at the Villa Mirador. Churchill greeted Roosevelt warmly, recalling later, “It gave me intense pleasure to see my great colleague….”

Churchill’s own flight from Britain had been plagued with bad luck, and he counted himself lucky even to be there in one piece. It was ironic, considering Churchill’s journey the year before, but the prime minister’s plane was not a Boeing 314 but a converted Consolidated B-24 bomber named Commando. It was comfortable enough, but had been designed for delivering bomb payloads, not VIP civilian passengers. Certainly, it could not match the spacious accommodations of the Clippers.

However, the trouble really began when Commando was already airborne. It was 2 am, and Churchill was sound asleep. He suddenly awakened with a burning sensation in his toes. A gasoline-fueled heater was going haywire and seemed on the verge of becoming red hot. If this happened, the prime minister’s blankets might burst into flames.

The cabin was heavy with the bitter stench of gasoline, and it was possible that a fire might lead to an explosion. Churchill woke up others in his party, and the heaters were all turned off. It was winter, and they were flying at 8,000 feet, which produced an intense cold that had everyone shivering. Churchill decreed that it was “better to freeze than to burn,” so the heaters were kept off. A midair explosion had been narrowly averted. Churchill, indulging in a bit of British understatement, later remembered the incident “struck me as a rather unpleasant moment.”

The Casablanca Conference was one of the milestones of World War II. Churchill was the leader of a country that had been taxed almost to the limits of its resources. By 1943, Britain’s manpower had been fully mobilized and could contribute nothing more. The immense power of the United States meant that Churchill, slowly but inexorably, would be reduced to a junior partner in the Allied coalition.

The prime minister had few chips, but he played his hand brilliantly. Roosevelt was inclined to favor Churchill’s ideas, but he still had to overcome the opposition of men like General Marshall and Admiral King. In the end, Churchill had his way. Sicily would be the next objective, not a cross-Channel invasion of France as many Americans had wanted.

Churchill was probably correct that the time was not yet ripe for a successful invasion of Nazi-occupied France. On the other hand, events did not bear out Churchill’s vision of Italy as the “soft underbelly of Europe.” The Italian campaign would prove a bloody nightmare for the Allies; the mountainous terrain favored the defense, and the Germans bitterly contested every inch of soil.

All this would be in the future. In January 1943, the Casablanca Conference was deemed a success by all parties. Roosevelt also declared the policy of unconditional surrender, Churchill readily agreeing. There would be no Western Allied negotiations with the Axis, a prospect that must have reassured the ever-suspicious Soviets.

When the conference business concluded, it was time for a little excursion. At Churchill’s urging, the two men motored to the famed oasis of Marrakech, about 150 miles from Casablanca. Ascending a tower, Churchill and Roosevelt viewed the snowcapped Atlas Mountains, dyed crimson by the rays of a setting sun. At last, though, it was time for Roosevelt to go back to the United States.

A C-54 transport arrived at Marrakech to pick up the president and take him back to Bathurst where the Dixie Clipper awaited him. Churchill was there to see him off, casually dressed in slippers and his famous ”zip” overalls. The C-54 taxied off the runway and lifted off at 7:45 on the morning of January 25. Roosevelt arrived at Bathurst safety, but was not quite ready to go back home.

The chief executive took a short excursion up the Gambia River, following up with a brief C-54 jaunt to Monrovia, Liberia. He visited various facilities and conferred with Liberia’s President Edwin Barley. This was fitting, since Liberia had been founded in the 1820s as a refuge for freed African-American slaves. The 690-mile round-trip flight from Bathurst to Monrovia, the Liberian capital, had taken seven hours.

Once the president returned to Bathurst, plans went ahead to take him back across the Atlantic. He boarded the Dixie Clipper in the evening, the massive plane lifting off a little after 11:30. The westward passage was not as smooth as the outbound journey. Captain Cone tried various altitudes in an effort to locate a patch of calm air, finally finding it at 1,000 feet. The Boeing 314 maintained this relatively low altitude for the remainder of the 1,841-mile trip from Africa to Brazil.

Indeed, Roosevelt needed all the rest he could get. A sick man, he was developing cardiovascular problems. The burdens of a presidency now entering its 10th year were beginning to take their toll. Roosevelt was tired from the long trip and hard work of the conference and had developed a fever on the return journey.

Dixie Clipper landed at Natal, Brazil, at 7:50 am local time. Roosevelt deplaned and was ferried to the seaplane tender USS Humbolt. Once aboard, he conferred with Brazil’s President Getulio Vargas. The two leaders were old friends, and they chatted amicably on deck while photographers recorded the historic occasion. During the trip from Africa to Brazil, the Atlantic Clipper had developed engine trouble. Number 3 engine had begun to spit oil, indicating a piston had blown. The engine was shut down, and though the Atlantic Clipper landed in Brazil safely it would have to undergo repairs. The American Clipper, another Boeing 314, was sent to replace the ailing flying boat.

Dixie Clipper and American Clipper were ordered to Port of Spain, Trinidad, to await further orders. The president and his party would join them there, taking C-54s from Brazil to Trinidad instead of the flying boats. The two C-54s did an admirable job, flying 2,135 miles in 11 hours and 15 minutes. After a brief sojourn at Port of Spain, which included the usual inspections and dinner, Roosevelt was driven to Cocorite Airport, where his old friend Dixie Clipper awaited him. Dixie Clipper and American Clipper lifted off at 7:10 on the morning of January 30.

January 30 wasn’t just any day, but Franklin Roosevelt’s 61st birthday. About noon the president was carried into the spacious dining salon and seated next to a window for a gala—and very unique—airborne birthday party. Bright red tropical flowers added vibrant color to the dining salon, and each table was covered with immaculate linen. Champagne was served, everyone lifting their glasses to toast the beaming chief executive. After a delicious luncheon of roast turkey, cranberry sauce, peas, potatoes, and coffee, the dishes were cleared for the president’s candle-laden birthday cake.

Roosevelt now took command, cutting the first slice of cake while traveling 8,000 feet above the sparkling blue Caribbean. The president was surprised by a series of unexpected birthday gifts, including rare Trinidad prints, a carved cigarette box, and two fancy egg cups.

The globetrotting Dixie Clipper touched down in Florida’s Biscayne Bay at 4:35 on the afternoon of January 30. Before departing for the train that would take him back to Washington, Roosevelt extended a warm and very sincere thanks to the Pan Am Clipper crews for a job well done.

Indeed, the Dixie Clipper had chalked up an impressive series of firsts as Roosevelt’s air carrier. It was the first airplane to carry a president across the ocean, the first to touch three continents by air, and the first to cross the equator four times. Of Roosevelt’s total journey, 70 hours and 21 minutes had been aboard Boeing 314 Dixie Clipper.

However, the era of the great flying boat would soon be coming to an end. As land planes extended their range and more airports of the world were surfaced to handle heavier aircraft, the advantages of flying boats were rendered nil. One cannot help but admire the magnificent achievements of Boeing flying boats like Dixie Clipper.

It should be remembered that at least some legs of the journey were aboard C-54 transport planes. The C-54s performed so well, it was decided that Roosevelt should have one as an officially designated presidential aircraft. Aircraft manufacturer Donald Douglas was happy to comply, creating a special version of his DC-4 (C-54 was its military designation). This C-54 Skymaster had a cruising speed of 250 mph and a range of 3,900 miles. It had some special adaptations, such as an elevator to lift the wheelchair-bound president on and off the plane.

This airplane was called Sacred Cow. Roosevelt used it only once, when going to the Yalta Conference early in 1945. He traveled to the island of Malta aboard the cruiser USS Quincy, then transferred to the Sacred Cow for the flight to Saki (near Yalta). Two months later he was dead, but his successor, Harry S. Truman, loved to fly and used Sacred Cow on a number of occasions.

The C-54 was an outstanding aircraft, but pride of place still belongs to the Boeing 314 flying boats. It can be rightfully argued that the Dixie Clipper was the first presidential airplane, ancestor in spirit if not in fact to the current Air Force One, a modified Boeing 747-200B.

Eric Niderost is a community college professor who writes from Hayward, California. He has written over 350 articles to date, including many on WWII. He is the coauthor of Civil War Firsts: Legacies of America’s Bloodiest Conflict.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments