by Paul B. Cora

Built in the mid-1930s as one of the famed Treasury class of large U.S. Coast Guard cutters, USCGC Taney had a distinguished career spanning five decades of continuous service. Taney’s remarkable history includes a significant combat record during World War II which placed the ship in harm’s way from the beginning of the Pacific War in 1941 through Japan’s surrender in 1945, with stints of convoy escort duty in the Atlantic along the way. Now preserved as a museum in Baltimore, Md., visitors to the historic vessel can gain a poignant appreciation for the actions and efforts of Coast Guardsmen in World War II while exploring one of the ships they took into battle.

When commissioned, the seven Treasury Class cutters were the largest and most capable ships in U.S. Coast Guard service, a distinction which Taney and her sister ships retained until the 1960s. They were built in the midst of the Great Depression at three U.S. Navy shipyards and benefited from exemplary workmanship, which partly accounted for their lengthy active careers. At 327 feet long with a beam of 41 feet and originally displacing 2,000 tons, they were steam-turbine driven, single-rudder, twin-screw vessels with stout hulls made from half-inch thick riveted steel plates.

Designed for peacetime missions of law enforcement, search and rescue, and maritime patrol, the Treasury Class cutters had a top speed of 20 knots and original armament consisting of two 5-inch deck guns and two 3-pounder saluting guns. As would be proved time and again, especially during World War II, the amazing adaptability of their basic design gave the “327s” an unsurpassed ability to meet changing roles and daunting challenges.

Taney’s keel was laid down at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on May 1, 1935. Built alongside three of her sister ships, Campbell, Duane, and Ingham, the new cutter was christened Roger B. Taney on June 3, 1936 (the name was shortened to simply Taney in 1940), for the chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court at the time of the famous Civil War era Dred Scott Decision. After commissioning that October, the ship transited the Panama Canal and arrived at her first duty station, Honolulu, Hawaii, the following January. Taney was destined to be known as “The Queen of the Pacific.” Most of her operational career would be in that ocean. In the years immediately before the outbreak of World War II, the cutter carried out search and rescue duties, chased opium smugglers off Hawaii, and supported American interests in the Line Islands along the Equator.

By 1940, the possibility of war sparked U.S. Navy interest in the Treasury Class cutters, and as a result, Taney and her sister ships received substantial armament upgrades, giving them antiaircraft and anti-submarine capabilities. During two successive refits in 1940 and 1941, Taney received a battery of .50-caliber antiaircraft guns, additional .50-caliber machine gun mounts, sonar equipment, stern depth charge racks, and depth charge throwing Y-guns. In July 1941, the 327s were transferred from the Treasury Department to the Navy in expectation of war, though they retained their Coast Guard crews. While Taney’s sister ships joined U.S. Navy units in North Atlantic patrols, “The Queen of the Pacific,” now resplendent in a coat of Navy gray paint and officially known as the USS Taney CG, began operations out of Honolulu as a unit of Destroyer Division 80, Inshore Patrol Force. If war broke out, the cutter’s primary duty would be anti-submarine patrol off the mouth of Pearl Harbor.

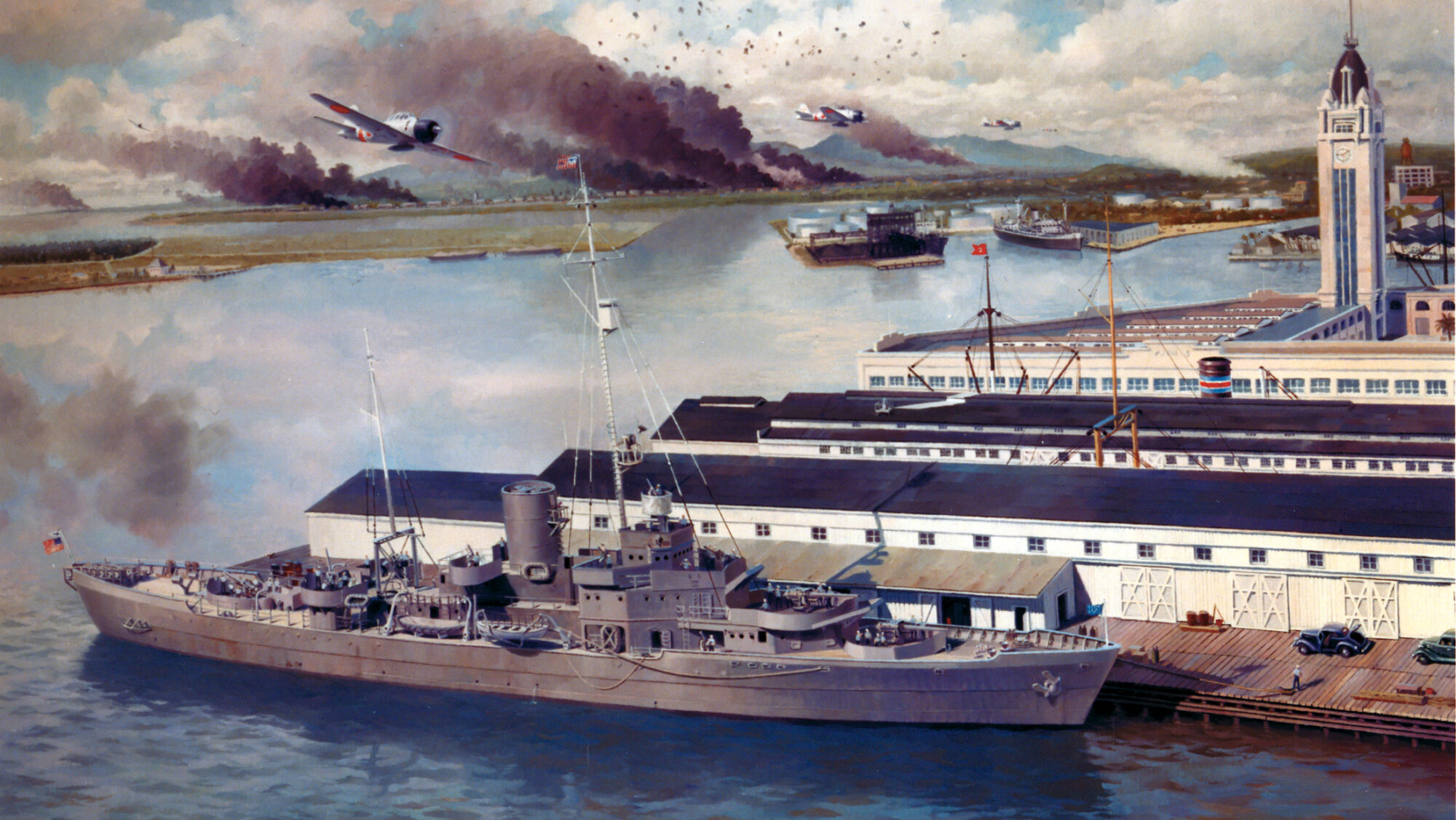

The morning of December 7, 1941, found Taney tied up at her home berth of Pier 6 near Honolulu’s Aloha Tower. The first inklings of what was in store came shortly before 7 am when operators on watch in the cutter’s radio room copied an unusual message from another unit of Destroyer Division 80: the USS Ward reporting that it had attacked and sunk an enemy submarine in the approaches to Pearl Harbor. Sensing from the message a dramatic turn of events, the officer of the deck (OOD) on duty that morning immediately recalled all officers from shore and had the crew stow the ship’s deck awnings, remove gun covers, and bring up ammunition from the magazine.

After clearing the ship for action, the Coast Guardsmen waited to see what, if anything, would happen next. Suddenly, around 8 am, the sky to the northwest came alive with antiaircraft bursts as Navy ships commenced a frantic defense of Pearl Harbor some eight miles away. Commander Louis B. Olson, USCG, Taney’s captain, gave the order to sound general quarters and then called for steam in preparation for getting underway. Though some of the ship’s officers had not yet made it back aboard, Olson later reported that the ship’s “anti-aircraft battery as well as all other guns were ready to fire with their full crew and three officers at their stations within four minutes.”

As the battle raged, the sky over the fleet anchorage turned black from the smoke of burning ships, and Taney’s crew waited for a chance to open fire should enemy planes approach Honolulu. An hour after going to battle stations at 9:01 and again at 9:15 several scattered formations of Japanese planes came overhead and Olson gave the order to commence firing. On Taney’s fantail, the ship’s two 3-inch antiaircraft guns went into action firing some 27 rounds of shrapnel ammunition at the raiders whose distance and altitude was just outside effective range. The remainder of the ship’s guns, though manned, stood in silent frustration—the forward 3-incher would not bear, and the 5-inch main armament was useless against aircraft.

Writing in his diary shortly after the attack, Taney radioman Maurice Thoresen recorded the uncertainty of December 7th’s morning hours. “We thought it was a drill as we have them frequently, but we heard gun fire in the direction of Pearl Harbor. That still did not give us a clue as to what was going on, because quite often the units practice firing at sleeves towed by planes. It was not until some planes approaching Honolulu were identified as Jap that we started firing on them. We did not know what this was all about. Everyone in the crew expressed their thoughts, but still couldn’t believe that we were being attacked… Sirens were wailing and we could see Army trucks speeding back and forth.”

During the morning, confusion reigned as Japanese aircraft not only attacked Battleship Row and the adjacent facilities, but also hit Army, Navy, and Marine Corps installations throughout Oahu. While the bulk of Japanese aircraft had completed their attacks by 10 am, small groups of planes continued to appear until almost noon. At Pearl Harbor, Japanese bombers were fired on by a number of U.S. ships between 11 and 11:35.

“The Officers and Crew Bore Themselves Well Although Most Members of the Crew had no Training Except Drill and had Never Seen Anything Above a .50-Caliber Fired.”

In Honolulu, Taney’s crew remained at battle stations throughout the morning in case the raiders reappeared over the city. Aside from the billowing smoke visible over the fleet anchorage in the distance, Honolulu took on an eerie cast as the smell of burning buildings and sounds of explosions hung over the city. Numerous antiaircraft projectiles from Navy ships at Pearl Harbor detonated after missing their targets.

At 11:35, a small formation of Japanese planes flew over Honolulu, and the crew of Taney’s forward 3-inch gun was able to sight in and open fire briefly, though to no avail. Finally, just before noon, the cutter’s gun crews were able to engage a target at close range. “At 11:58,” reported Commander Olson, “a formation of five enemy planes approached the vessel directly from the south southwest over the harbor entrance on what appeared to be a glide bombing or strafing attack on this vessel or more probably … the power plant which is located north of the vessel’s berth at Pier Six … ” Every gun that would bear opened up on the planes, which were “rocked by the fire and swerved up and away.” Olson was also able to report, “Several .50 caliber tracers appeared to pierce the wing and tail structure of one plane,” before the attackers changed course to avoid the barrage.

No further Japanese air activity was witnessed over Honolulu, and by afternoon Taney’s gun crews were permitted to relax at their stations. “The officers and crew,” reported Olson in the wake of the attack, “bore themselves well although most members of the crew had no training except drill and had never seen anything above a .50-caliber fired.”

As American forces in Hawaii sought to recover from the shock of the Japanese attack, the pre-dawn hours of December 8, 1941, found USCGC Taney bound for her pre-assigned anti-submarine patrol area between Honolulu and the entrance to Pearl Harbor. From December 8-14, the cutter made seven depth charge attacks on suspected Japanese submarines, including a notable one on December 10. That evening while patrolling with the USS Ramsay (DM-16), Taney picked up a strong sonar echo and dropped a pattern of depth charges on a spot some three miles off Honolulu. A short time later, a large oil slick appeared over the spot and remained for two days, leading to speculation that a sub may, in fact, have been hit.

In the weeks following the Pearl Harbor attack, the dramatic transition to combat operations required some adjustment for Taney’s Coast Guard crew. “The first few days were hard on all the crew due to all of the battle station alarms and the dropping of depth charges,” crewman Maurice Thoresen wrote in his diary. “We began to condition ourselves so that when the depth charges were dropped we could tell that it was not a bomb or torpedo hitting us. The depth charges go off with such a terrific explosion that the whole ship would shake and shudder. The ship also reacts the same way if we are close enough when the destroyers drop their depth charges.”

Taney’s patrol duties off Oahu eventually became routine for the ship and crew in between convoy escort duties and special assignments. As Robert Guenther, a Taney crewman who reported aboard as a seaman in early 1943, later recalled, the cutter was often “killing time in between assignments by being on what was called the ‘easy circle’ which was anti-submarine patrol between Barber’s Point and Diamond Head, and that covered both the entrance to Pearl Harbor and the entrance to Honolulu Harbor. We would go back and forth for 12 days and then have two days in port and then back again for 12 more days … on other assignments. We were taking supplies to what was called the Hawaiian Sea Frontier which was, on the northwest, Midway Island, south of that was Johnson Island, south of that was Canton Island, and then northeast of that was Palmyra Island, and then back to Honolulu. So the ship would escort supply ships and tankers to those outlying posts so that they could be supplied with food and with fuel and that would be about a three week trip each time around.”

On one special mission to the Line Islands, some 1,600 miles southwest of Hawaii, in July 1943, a Japanese patrol bomber nearly brought an end to Taney’s active career. According to Guenther, Taney was returning from Palmyra Island when the ship received orders “to take a surveying crew from the Seabees to a place called Baker Island to see if it was feasible to put an airbase … there to help with the invasion of Tarawa … And while we were getting ready to offload our Seabees on the island, we were discovered by a Japanese patrol plane.”

Homer Compton, a boatswain’s mate in Taney’s deck force, described years later the ship’s close encounter with Japanese bombs. “We arrived at Baker about two hours before sunset. The 5-inch gun crew aft was to make up the landing party (not knowing if the island was occupied by the Japanese). Rifles and grenades were issued. The power launch would tow the landing boat to the surf and then wait for their return… We were soon spotted by a ‘Mavis’ Japanese bomber. Needless to say at this point the landing was delayed. As our 3-inch guns put up a great amount of flak, the Mavis lined up for an aft to forward run.”

As the enemy bomber began a shallow dive, Taney used speed and evasive action to present a difficult target, causing the Japanese pilot to initially break off his attack. “Unable to get us in their bomb sights they circled for another run,” recalled Compton. “We made ready our guns and soon they were blazing away. Then the vapor streams and bombs away. With full steam ahead and left full rudder we knew it was a matter of seconds. Everyone that wasn’t on a gun hit the deck.” Though two explosions rocked the ship from near misses, the violent maneuvering paid off and the Japanese bomber eventually departed, as did the cutter in case additional planes should appear. Two weeks later, this time accompanied by air support, Taney returned to Baker Island to complete the assignment.

The men who made up Taney’s crew during World War II were mostly volunteers who joined the Coast Guard looking for something like the Navy, but more distinctive and close-knit. At its peak wartime strength of just over 214,000, the Coast Guard had only 16,000 draftees in its ranks. Depending on their “rate” or trained specialty, Coast Guardsmen assigned to the larger ships were often aboard for lengthy tours of duty and often came to look with unusual pride on their particular ship.

Guenther explains, “There was great pride because in the Navy, basically, you had an 18-month tour of duty and then you were transferred off. But many of us on the Taney stayed for up to three years because there was nowhere else to go with our rate—there was no place for a radarman to go except on a major Coast Guard ship. So, you became very, very close to your ship.”

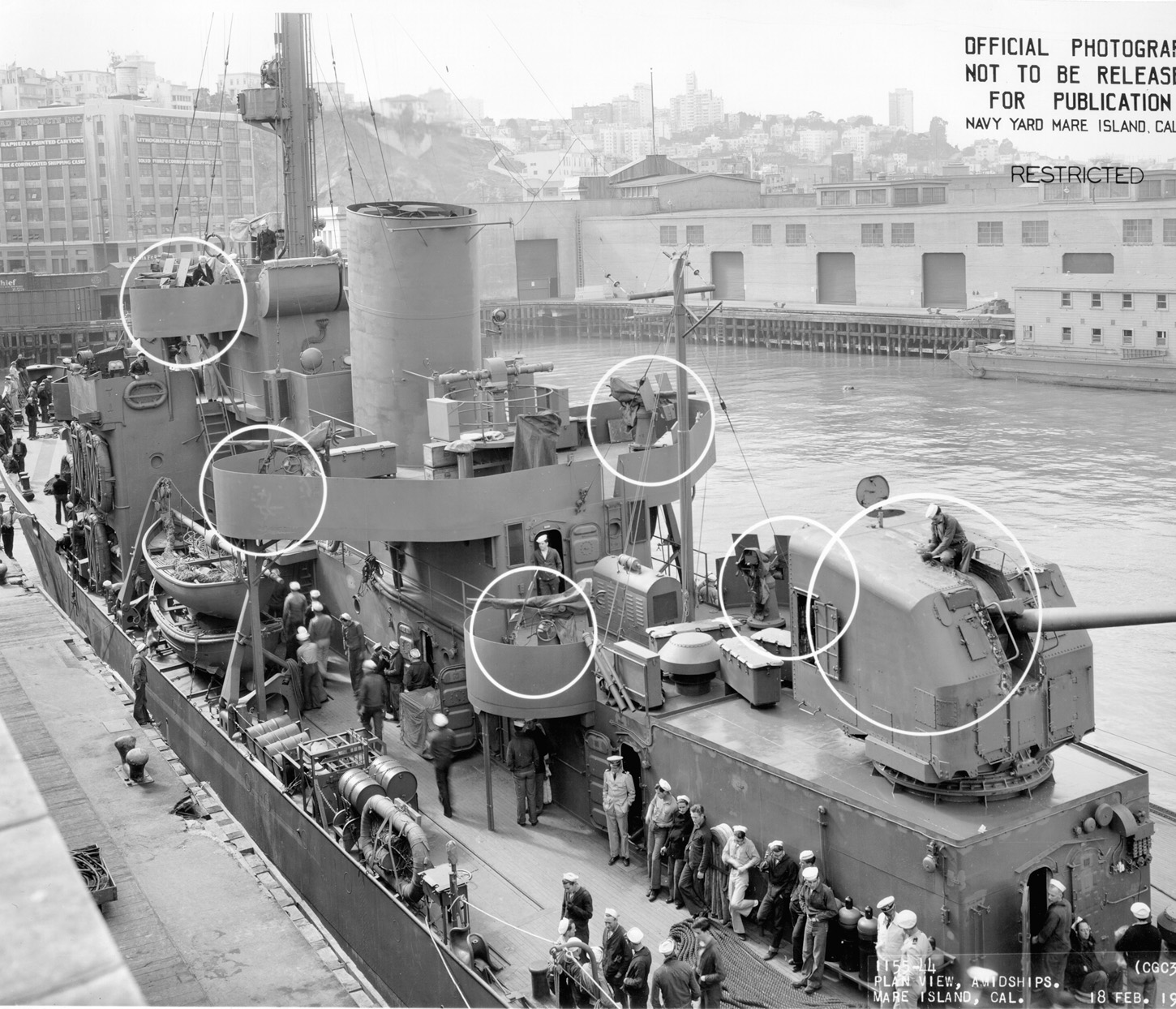

After almost two years of wartime operations, “The Queen of the Pacific” returned to Calif. to undergo another major armament upgrade. In refits carried out at Alameda, California, and later Mare Island Navy Yard, Taney lost her somewhat dated 5-inch and 3-inch guns, receiving in place four enclosed-mount 5-inch dual purpose guns usable against both surface targets and aircraft. For close-in antiaircraft capability, eight 20mm rapid-fire cannons were mounted throughout the bridge and superstructure, though later in 1944 two of these would be replaced by harder-hitting twin 40mm mounts. Depth charge racks and throwers were retained, and the ship’s anti-submarine capability was boosted by the addition of a forward-firing hedgehog anti-submarine weapon. Unlike depth charges, hedgehogs were fired ahead of the ship at an enemy submarine’s approximate position and were designed to explode on contact. Finally, Taney received new surface and air-search radars giving the cutter advanced detection capabilities.

Once finished at Mare Island, orders for the Atlantic awaited Taney, and after transiting the Panama Canal the cutter arrived at the Boston Navy Yard for an additional upgrade to the ship’s combat information center (CIC). After this work was completed, the crew carried out gunnery training at Casco Bay, Maine, before receiving its first Atlantic combat assignment. With excellent sea keeping qualities, speed, and armament, Taney’s sister ships had proved themselves to be first-class escort vessels and had borne the brunt of the convoy battles against German U-boats during the previous two years.

The Taney Slowly Made Its way Across the Atlantic, Continuously on Watch for German U-Boats and Aircraft Which Might Attack the Merchant Ships at Any Time.

Taney’s job in 1944 would be to lead a force of anti-submarine vessels assigned to convoys traveling between the East Coast of the U.S. and North Africa. “Most of them were destroyer escorts,” recalled Guenther, who returned to Taney in 1944 after training as a radarman. “[A] few of them were Coast Guard manned, a few of them U.S. Navy manned, a few of them from foreign countries… There were a total, on those major convoys, of 13 escorts and the Taney was in command of them.”

Throughout her Atlantic convoy stint, Taney served as flagship for Task Force 66, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, under Navy Captain W.H. Duvall. The first of six Atlantic convoy runs began on April 2, 1944, when 85 ships of convoy UGS-38 gathered off Hampton Roads Va. bound for the Mediterranean. Using Taney’s communications gear and powerful surface and air-search radars, Duvall could effectively keep track of the convoy’s merchant ships and coordinate the escorts. With Taney steaming 4,000 yards ahead conducting radar and sonar sweeps, the convoy slowly made its way across the Atlantic, continuously on watch for German U-Boats and aircraft which might attack the merchant ships at any time.

On April 20, the convoy had passed through the Strait of Gibraltar and was off the coast of Tunisia. That evening, at approximately 9 pm hours, a force of German Junkers Ju-88 and Heinkel He-111 bombers suddenly appeared out of the darkness and commenced torpedo attacks on the massed cargo ships and their escorts. Though enemy reconnaissance planes had been spotted earlier in the day and several suspicious radar contacts had caused alarm, the torpedo attack came without warning since the bombers approached at low level using the African coastline to screen their movements from radar.

As visual recognition of the German raiders was made, the sound of the general alarm sent Taney’s crew racing for its battle stations. Within minutes the sky suddenly erupted in blinding light as the merchant ship SS Paul Hamilton, loaded with ammunition and troops, exploded following a German torpedo hit. All eyes aboard Taney turned toward the spectacle as the ship disintegrated with a deafening roar, taking with it nearly 550 men. Taney’s 20mm and 40mm antiaircraft guns opened up on the raiders, which continued to make low-level attacks up and down the rows of ships. Although the 5-inch gun crews took their stations, they were not permitted to fire at the low-flying Germans for fear of hitting the other ships in the convoy.

Shortly after SS Paul Hamilton exploded, the destroyer USS Lansdale (DD-426) took two aerial torpedoes and broke in half with the loss of 47 of her crew. In subsequent attack waves Taney narrowly dodged a pair of torpedoes while two more merchantmen were hit. Anti-aircraft gunners throughout the convoy sent tracer ammunition arching in all directions, making the danger of friendly fire casualties suddenly very real. While shooting at the raiders, three Coast Guardsmen on Taney were hit by shrapnel from the fire of other ships during the 17-minute battle.

When the last of the enemy aircraft departed, damage was assessed and survivors were picked up from the water, including several German airmen from the estimated six planes shot down during the attack. In addition to the total loss of SS Paul Hamilton and the destroyer Lansdale, three merchant ships had been badly damaged. Once the elements of convoy UGS-38 broke off at their various destinations, Taney proceeded to Birzerte, Tunisia, picking up the U.S.-bound convoy GUS–38 on May 1, 1944. The 107 merchantmen of the convoy were delivered safely to American ports some two weeks later in spite of U-boat activity, which claimed several escort vessels along the way. On May 3, the Coast Guard-manned USS Menges (DE-320) was hit by an acoustic homing torpedo from a U-boat while investigating a radar contact several miles astern of the convoy. Twenty-six Coast Guardsmen were killed, though the ship was ultimately saved. Two days later, as convoy GUS-38 was approaching Gibraltar, the destroyer USS Fechteler was torpedoed and sunk with the loss of 29 crewman.

Taney continued to serve as the flagship for Task Force 66 on four more convoys between the U.S. and the Mediterranean during 1944, though none was as eventful as the first had been. On October 8, 1944, the cutter was detached from flagship duty and proceeded to the Boston Navy Yard for what would be her last and most dramatic wartime refit. When the ship emerged from Boston three months later, her appearance bore almost no resemblance to when she arrived; gone were the clean lines of a first-class escort vessel, and in their place the ungraceful and boxy silhouette of an amphibious command ship (AGC).

AGCs were designed to function as headquarters platforms for amphibious operations, and Taney’s modifications featured living and working spaces for an admiral and staff, as well as sizable communication facilities. The new command spaces were housed in a large superstructure section added behind the cutter’s bridge. Gone, too, were the 5-inch enclosed gun mounts and hedgehogs, though in their place was a sizeable antiaircraft battery composed of three twin 40mm guns and a multitude of 20mm guns arranged throughout the ship. Two 5-inchers were retained on the main deck forward and aft, but the splinter shield enclosures were removed to save weight.

Following sea trials out of Boston, Taney headed south to complete gunnery training with her new armament off Hampton Roads and then steamed for the Pacific via the Panama Canal. On February 22, 1945, the cutter arrived at Pearl Harbor and was quickly designated as flagship for Navy Rear Admiral Calvin H. Cobb USN. Once the admiral’s staff joined the ship, Taney’s complement reached its peak of 250 officers and men—nearly twice the number the ship was originally designed to accommodate.

36 Ships Sunk and Another 368 Damaged in What Became the Costliest Campaign in U.S. Navy History.

Underway from Hawaii again on March 10, 1945, Taney headed for the Western Pacific where the war’s last great battle, the invasion of Okinawa, was poised to begin. As commander of Task Group 99.1 and prospective commander of naval forces in the Ryuku Islands, Cobb’s role in the coming campaign would place USCGC Taney in harm’s way as never before. During the Okinawa campaign, Japan would unleash over 1,900 kamikaze planes against the U.S. fleet; 36 ships would be sunk and another 368 damaged in what became the costliest campaign in U.S. Navy history.

After a week spent waiting for orders at Ulithi, Taney weighed anchor on April 7, 1945, and in four days made her way to the Hagushi landing beaches on Okinawa’s west coast where Marine and Army troops went ashore on April 1.

On just their first day off Okinawa, Taney’s crew was called to general quarters three times when Japanese planes attacked the anchorage, setting the stage for the weeks to come. At 5:43 hours the next morning, the general quarters alarm sounded again as a twin-engine “Betty” bomber streaked over the anchorage at low level. The Japanese raider crossed Taney’s bow at only 1,200 yards range, and the ship’s forward 20mm gun crews opened fire, repeatedly hitting the plane which crashed into the sea nearby.

Except for periodic refueling at Kerama Retto off the southwest coast of Okinawa, Taney remained anchored among the transports at Hagushi for her first month in the campaign. Japanese air raids and kamikaze attacks took place daily, and in addition to putting up a great volume of antiaircraft fire, Taney and the other ships at anchor relied on heavy smoke screens for protection. After 27 days awaiting further orders off Hagushi, Taney weighed anchor on May 11, 1945, and proceeded to the southern anchorage off the island of Ie Shima, three and a half miles west of Okinawa. There, Rear Cobb relieved Rear Admiral L.F. Reifsnider as commander of Task Group 51.21 and senior officer present afloat (SOPA), responsible for directing all local naval activities off northern Okinawa.

Ie Shima’s southern anchorage proved to be a far more exposed location than Taney’s former position off Hagushi and in the coming weeks the ferocity of Japanese air activity would reach its peak. For the cutter’s first few days at Ie Shima, Japanese harassing raids took place every night bringing the crew to battle stations where they remained for long hours.

On May 18, air activity intensified, and in addition to several early morning alerts Japanese aircraft returned that evening to attack transport ships off Ie Shima. Shortly after going to general quarters at 7:30 am, Taney’s gun crews opened fire on a Japanese “Kate” torpedo bomber turned kamikaze sending it crashing into the sea nearby, the first of four kamikazes officially credited to the cutter’s guns. During the next four hours, the enemy raided the anchorage five more times and the Coast Guardsmen aboard Taney witnessed the destruction of the nearby LST-808 by torpedo planes.

After a relatively quiet day on May 19, kamikazes struck at Ie Shima again on the evening of May 20, 1945. During the attack, Taney’s gun crews added to the ship’s score when a pair of kamikazes attempted suicide runs on nearby transports. According to Taney’s war diary, the first plane “approached [the] ship from … an estimated altitude of 1,000 feet when taken under fire by main and secondary batteries,” after which the plane veered away in a tight circle. After leveling off, one kamikaze was suddenly rocked by a 5-inch burst and hit repeatedly by 40mm and 20mm fire, causing it to crash into the sea next to a Dutch freighter.

After splashing the first plane, Taney’s antiaircraft batteries immediately shifted to a second kamikaze, which was spotted boring in on the cutter from an altitude of just 800 feet. A well placed 5-inch round exploded immediately in front of the aircraft, and “[the] plane seemed to halt abruptly and then went into a steep dive,” crashing into the hulk of the LST-808 abandoned two days before.

Japanese raids continued in succeeding days, and with so much strain it is not surprising that at least one friendly fire incident took place. On the morning of May 21, a stray Navy F6F Hellcat unwisely approached the anchorage at Ie Shima from the same direction as several recent air attacks. Unable to identify the plane from head-on, Taney’s gun crews held fire until the last minute as the fighter inexplicably flew toward the ship at low level. Once Taney’s and the neighboring ships’ guns opened fire, the plane veered away revealing U.S. markings. Although fire was abruptly ceased, the fighter had been hit and crashed nearby. The pilot did not survive.

Japanese air activity reached its violent peak over Ie Shima during the last week of May 1945, and for three and a half days starting on the evening of May 24, Taney remained almost continually at general quarters in what became the most combat intensive period in the ship’s history. At sunset on May 24, raiders from mainland Japan came over Ie Shima, bombing the airfield and shore installations. It was a long night as 34 separate waves of planes streaked over the anchorage to bomb and strafe. Finally at 4:40 am on May 25, Taney secured from general quarters so that those not on watch could sleep.

Rest on Taney was short-lived that morning, and a furious series of attacks began at 7:55 am hours. Within five minutes of the alarm, Taney’s gun crews opened up on a kamikaze whose pilot had begun a suicide dive at the nearby merchant ship SS Brown Victory. Amid a hail of 5-inch, 40mm, and 20mm fire from the cutter, the plane was hit numerous times and swerved out of control, just missing its intended target as it splashed into the sea. There was little time for cheering as more kamikazes arrived.

At 8:04 am, Taney opened fire on another kamikaze, which crossed overhead, then dove straight into the nearby minesweeper USS Spectacle (AM-305), tearing a massive hole in the side of the small ship and knocking many of those crewmen who had been manning her guns into the water. A short time later, another suicide plane slammed into the landing ship LSM-135, which had begun picking up survivors from the stricken minesweeper, turning it into a blazing hulk. During a brief lull in the attacks all hands remained at battle stations tensely awaiting what would happen next. Shortly after 11 am, the anchorage suddenly came alive with antiaircraft fire, and at 11:20, Taney’s crew observed a large explosion in the distance as the small troop transport USS Bates (APD-47) fell victim to yet another Japanese suicide plane.

A short time after Bates was hit, the attacks subsided, but Taney’s crew remained at its stations, nervously searching the sky. The ferocity of the attacks had been enough to unsettle even the steadiest among them who could only wonder at the suicidal determination of the enemy pilots. Taney had been a very lucky ship so far, especially since a number of smaller vessels had already been singled out by kamikazes.

The morning of May 25 had been a costly ordeal for the American ships off Ie Shima. Japanese raiders did not return until the afternoon of May 26, and these were fortunately driven off by Navy planes of the combat air patrol. During the respite from the kamikaze attacks, signalmen on Taney received a message sent by flashing light from the SS Brown Victory referencing the cutter’s effective gunfire of the previous day, “Thanks very much for saving our fannies.”

Air attacks continued on the morning of May 27 when a group of 10 Aichi “Val” dive bombers raided the anchorage and were driven off by patrolling U.S. fighters. Sustained bombing attacks again started at sundown, and Taney’s crew remained at battle stations throughout the night, securing only at 5:30 the next morning. When the ship’s CIC finished adding them up, they calculated that 125 Japanese planes in 46 separate waves had come over Ie Shima during the night.

Most Agreed That Taney’s Luck Should Have Run Out Off Ie Shima.

Almost as soon as Taney secured from general quarters that morning, the weary crew was again called to battle stations as another attack wave approached the anchorage. A four-plane flight of Vought F4U Corsair fighters was spotted chasing a lone Japanese plane at 6:53, but it became clear that the Navy fighters would not catch it in time. Every gun on Taney that would bear opened fire as the plane went into a suicide dive. In spite of the hail of antiaircraft bursts and streams of tracers, which tracked the plane, the dive ended in a fiery crash onto a nearby merchant ship. SS Brown Victory’s luck had run out, and all hands aboard Taney watched in horror as the cargo ship, saved from a hit just days before, erupted in flames.

When the last of 15 separate raids abated at 9:30 on May 28, the weary Coast Guardsmen aboard Taney secured from battle stations in what became a two day respite interrupted only by the nightly harassing raids. The attacks of the previous days marked the end to the most desperate period in Taney’s wartime career, and statisticians later worked out that during the ship’s first 45 days off Okinawa the crew had been called to battle stations a total of 119 times.

On June 1, 1945, Cobb’s stint in command at Ie Shima ended, and the cutter Taney was given a period of comparative rest. Returning to the fleet anchorage of Hagushi, the ship saw nothing like an end to enemy activity, however, as Japanese raiders continued to attack targets in and around Okinawa on a daily and nightly basis. Throughout the summer of 1945, Taney remained at Okinawa, part of the time off Hagushi and later anchored in Buckner Bay off the eastern side of the island.

Manning the flagship for Cobb, Taney’s crew had little to look forward to but another role in an even bloodier campaign that would likely end the war—the invasion of Japan sometime that fall. By all estimates, resistance at Okinawa, suicidal as it had been, was merely a foretaste of that which could be expected in the coming campaign, and most agreed that Taney’s luck should have run out off Ie Shima.

The announcement of the Japanese surrender on August 15, 1945, brought preparations for another amphibious operation to an end. A week later, Cobb’s command, Task Group 95.5, was dissolved, and on August 29, he transferred his flag to the USS Texas after assuming command of Battleship Division 5. While the Coast Guardsmen in Taney’s crew looked forward to a return to the U.S., the cutter, which had seen action from the very first day of the war, was called on to carry out a final assignment. On September 9, 1945, Taney weighed anchor in Buckner Bay and steamed north, arriving two days later off Wakayama on the island of Honshu, Japan. There, the ship, which was the first Coast Guard cutter to enter Japanese home waters after the end of hostilities, assisted with the evacuation of Allied prisoners of war.

Finally, after serving as the headquarters for the Navy Port Director and weathering a major typhoon in the process, USCGC Taney steamed from Japan on October 14, 1945, bound for the U.S. When the cutter finally sailed beneath San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge some 15 days later, few who had seen the gleaming “Queen of the Pacific” before the war would have recognized the weary hulk that returned from Japan.

For the Coast Guardsmen who departed Taney at the end of the war, the ship they served on would always be remembered as “The Lucky Lady.” So often in the previous three-plus years of war, the cutter had steamed into harm’s way and had always returned with all hands, while others had assumed the same risks and had not.

After a major reconversion to her peacetime lines in 1946, USCGC Taney went on to carry out virtually every peacetime Coast Guard duty, including decades of ocean weather patrol and countless search and rescue and law enforcement missions. She even went to Vietnam for 10 months in 1969-70 where, for the first time since 1945, her 5-inch main battery fired in anger.

Forty years after America’s entry into World War II, Taney was still steaming the high seas, by which time the ship had acquired the distinction of being the last active U.S. warship to have seen combat during the December 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. In 1986, on the 45th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, Taney was finally decommissioned after a remarkable service career.

Unlike so many other ships of the same era that were sold for scrap or sunk as ordnance test targets, Taney received a second lease on life when, after decommissioning, the “Lucky Lady” was set aside as a floating memorial. Today, visitors to Baltimore’s Inner Harbor can walk decks where Coast Guardsmen who witnessed the “Day of Infamy” and braved the U-boat, torpedo, and kamikaze, once trod.

Paul B. Cora is the curator of the Baltimore Maritime Museum where he has been involved with the preservation of USCGC Taney since 1995. Mr. Cora holds a masters degree in history from the University of Maryland and is also an avid student of World War II Aviation. His published works include Yellowjackets! The 361st Fighter Group in World War II.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments