By Michael D. Hull

After the Battle of the Bulge delayed their advance by six critical weeks, the British, U.S., and Canadian armies went on the offensive in mid-January 1945 and pushed toward the German frontier.

They lined up on a broad front from north to south, with the British and Canadians in the north, the Americans in the center, and the Free French in the south. It was tough going as the enemy—retreating but fighting more desperately than ever—forced the Allies to pay dearly for virtually every yard gained. At the gates of their homeland, the German forces made full use of natural defensive barriers, including such rivers as the Rhine, Main, Ruhr, Maas, Weser, Elbe, and the Roer. They destroyed bridges and caused widespread flooding.

Defending a 38-mile front along the fast-flowing Roer River, from north of Monschau to north of Linnich, the powerful U.S. Ninth Army—a comparative newcomer to the European Theater—faced a daunting challenge early in 1945. Two days after the U.S. First and Third Armies had linked up at Houffalize on January 16, Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery, commander of the British 21st Army Group, ordered the Ninth Army to cross the Roer in Operation Grenade, the southern pincer of a two-pronged attack on the Rhineland. The jump off was tentatively set for February 10. Monty had assumed operational control of the Ninth Army on December 20 while supporting American units in the Ardennes offensive.

Simpson’s Army Sitting on the Roer

Grenade was planned to coincide with the Canadian First Army’s launch of Operation Veritable, the northern pincer, on February 8. Detailed planning for the Roer crossing had been started in early December, but everything hinged on the First Army’s securing the Roer’s seven dams. Before this was achieved on February 9, however, the Germans jammed open the dams’ discharge valves to cause a sustained overflow of the river, widening it to between 400 and 1,200 yards and rendering it almost impassable.

General Henry D.G. Crerar’s Canadian and British units attacked on schedule, but the Ninth Army had to wait impotently for the waters of the Roer to subside while their allies were left to fight alone. For 11 frustrating days, 56-year-old Lt. Gen. William H. Simpson, commander of the Ninth Army, kept a close watch on the water level. His combat engineers calculated that the Roer would be at its lowest level around February 25, but Simpson wanted to take the Germans by surprise, so he planned to launch his attack just before that date. A meticulous planner like his boss, Montgomery, Simpson decided that the river level would be low enough on the morning of February 23 for his troops to cross and for bridging operations to be undertaken.

His northern XIII Corps, led by Maj. Gen. Alvan C. Gillem Jr. and comprising the 29th, 84th, and 102nd Infantry Divisions, was to head east across the river, swing northward to link up with the Canadians, and then turn east toward the Rhine. Maj. Gen. Raymond S. McLain’s southern XIX Corps (8th, 78th, and 104th Infantry Divisions) would move northeastward and clear the Rhineland. A third corps, the recently activated XVI led by Maj. Gen. John B. Anderson, comprised the 8th Armored Division, the British 7th Armored (the famed Desert Rats), and the 35th Infantry Division.

While waiting for the Roer level to moderate, Simpson was able to build up his army to more than 300,000 men, 1,000 tanks, and 2,000 field guns in three corps totaling 11 divisions. He marshaled men and equipment under cover of darkness. While other U.S. Army formations were by then suffering a critical shortage of artillery ammunition, Simpson secured almost 46,000 tons and the largest concentration of firepower yet fielded by an American army on the Western Front. Montgomery, with his emphasis on “colossal cracks” of artillery, had ensured this.

The Ninth Army’s Breakout

At 2:45 on the gray, chilly morning of Friday, February 23, 1945, a tremendous artillery barrage lit up the dark skies as 1,500 guns of the Ninth, First, and British Second Armies hammered suspected German strongpoints across the River Roer. When the shelling died down after 45 minutes, Simpson started his assault across the river on a 14-mile front. The infantry of six divisions dragged their 15-man assault boats across the muddy shores and into the river.

The most northerly of the assault formations, Maj. Gen. Alexander R. Bolling’s 84th Infantry Division, jumped off from the center of Linnich across a relatively narrow section of the Roer. Leading troops of the 1st Battalion of the 334th Regiment paddled across the swollen river. The swift current swept away broadsiding boats, but the first infantry waves made it across with few casualties. Successive assault waves were peppered by enemy mortars and small arms fire until they reached the far side, but the casualties were still relatively light.

The orderly initial crossing was followed by chaos and delays. Boats were stuck on the far shore, some drifted downstream, and hastily laid wooden footbridges were broken up by enemy fire. Bolling’s 3rd Battalion was not able to start across the river until 6:45 am. Using a shuttle service of boats, the battalion completed its crossing at 10:35 am.

German planes and artillery homed in and pounded the crossing site, but the gallant infantrymen and combat engineers persevered. New treadway spans were laid, anchored to trees and assault craft, and more troops made it across the river. The 84th Division’s 1st Battalion took the enemy by surprise, captured the village of Korrenzig, and carved out a 4,000-yard bridgehead. Bolling’s entire 334th Regiment was over the river by 2:50 pm.

The Americans pressed on, and by the end of the day 28 of Simpson’s infantry battalions had crossed the Roer. Because of elaborate security precautions, he had caught the enemy by surprise and unable to mount a major counterattack. The construction of heavy bridging across the river was completed the next day, and on February 25, the Ninth Army linked up with Lt. Gen. Courtney H. Hodges’s U.S. First Army to form a 25-mile-long bridgehead from Baal to Duren.

Infantry and armor of the XIII, XIV, and XIX Corps, meanwhile, began pushing eastward and branching out. The Ninth Army linked up with the Canadians at Geldern on March 3, after reaching the Rhine opposite Dusseldorf the previous day.

Operation Grenade, which ended on March 5 and cost just over 1,400 casualties, was the Ninth Army’s outstanding contribution to victory on the Western Front. It inflicted 16,000 casualties on the Germans and captured 29,000. The action placed Simpson in the front rank of American field commanders, though he had been fortunate in facing 30,000 Germans in four understrength divisions and only 70 tanks, while Crerar’s Anglo-Canadian force battled 11 enemy divisions and suffered 15,634 losses in Operation Veritable. As Montgomery had planned, Crerar drew the German strength onto him, as General Sir Miles Dempsey had done at Caen, leaving Simpson to break through, as General Omar N. Bradley had done in Operation Cobra, the breakout from the Normandy beachhead, in July 1944.

“Texas Bill” Simpson: A “General’s General”

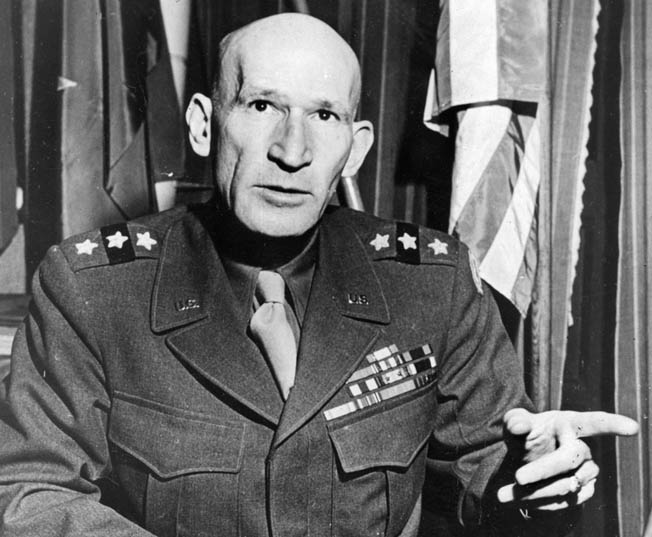

Simpson was justifiably proud of the performance of his army at the River Roer. A classic feat of maneuver, Operation Grenade had succeeded, with relatively light losses in men and equipment, in striking the enemy at vulnerable spots on his flank and rear. General Bradley, commander of the 12th Army Group, called the February 23 crossing “one of the most perfectly executed of the war.” Simpson, he said, was “steady, prepossessing, well organized, earthy, a great infantryman and leader of men,” and his army “a first-rate fighting unit.” General Ernest N. Harmon, the tough commander of the 2nd Armored “Hell on Wheels” Division, viewed Simpson as a “general’s general.”

Six feet, two inches tall, rawboned, and bald as a billiard ball, “Big Simp” also earned the praise of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Allied supreme commander. Citing Simpson’s “brilliant service,” he said later, “If he ever made a mistake as army commander, it never came to my attention…. Alert, intelligent, professionally capable, he was the type of leader that American soldiers deserve.” Respected by his men, his superiors, and his allies, General Simpson had many admirers and no detractors. Yet he remained one of the most astute but least known senior U.S. Army commanders in the European Theater. His army was the last American field army to be continuously deployed in northwestern Europe and the first to reach the Rhine and the Elbe.

Simpson in the Punitive Expedition and the Western Front

The son of a Tennessee cavalry veteran of the Civil War, William Hood Simpson was born on Saturday, May 19, 1888, in the little town of Weatherford, 40 miles west of Fort Worth, Texas. After attending the local school and playing football there, he secured an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at the age of 17. He attained the nickname of “Texas Bill” at West Point. He did poorly as a student and graduated second from bottom in the class of 1909, which included future generals George S. Patton, Jr., Robert L. Eichelberger, and Jacob L. Devers.

Commissioned a second lieutenant, Simpson joined the 6th Infantry Regiment at Fort Lincoln, North Dakota, and trooped with it to the Philippines for two years. After serving at the Presidio of San Francisco from 1912 to 1914, he was ordered to his home state on a border patrol assignment. Returning to his regiment after duty at the Panama Pacific Exposition in 1915, Simpson took part in Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing’s punitive expedition into Mexico in 1916.

After promotion to first lieutenant, Simpson served as an aide to Maj. Gen. George Bell, Jr., commander of the 33rd Division at Fort Logan, Texas. Promoted to captain in May 1917, Simpson accompanied Bell on an observation tour of the British, French, and U.S. armies in France later that year. The up and coming young officer returned to France when the 33rd Division embarked for the Western Front in April 1918. Receiving temporary promotions to major and lieutenant colonel, Simpson advanced to divisional chief of staff and attended the American Expeditionary Force General Staff School at Langres, France.

The lanky Texan saw action in the autumn of 1918. After training with Australian troops, the 33rd Division fought in the big American offensives at St.-Mihiel on September 12-16 and the Meuse-Argonne from September 26 to November 11. The division was inspected by King George V of England, who decorated some of its officers and men. Simpson earned the Distinguished Service Medal for his staff work and the Silver Star for gallantry. After occupation duty in Germany, Simpson returned home and became chief of staff of the 6th Division at Camp Grant in Rockford, Illinois, in May 1919. He reverted to the rank of captain on June 30, 1920, but was promoted to major the following day.

Between Two Wars

Early in 1921, Simpson began a two-year tour of duty at the War Department. That December, meanwhile, he took time out to marry Ruth (Webber) Krakauer, an attractive widow from London whom he had first met at West Point. They were wed in El Paso, Texas. After his Washington stint, Major Simpson entered the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia, graduated in 1924, and went on to the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He ended the course as a distinguished graduate in June 1925.

After spending two years commanding a battalion of the 12th Infantry Regiment in Maryland, Simpson entered the Army War College in August 1927. He graduated the following year and then taught military science and tactics at Pomona College in Claremont, California, from 1932 to 1936. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1934 and to colonel in 1938, and instructed at the Army War College from 1936 to 1940. He briefly led the 9th Infantry Regiment at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, rose to temporary brigadier general, and became assistant commander of the 2nd Infantry Division there.

Simpson in World War II

From April to October 1941, Simpson commanded Camp Wolters, Texas, was promoted to temporary major general, and took the helm of the 35th Infantry Division at Camp Robinson, Arkansas. Shortly after America entered World War II, he led the division to a training site in California. After further command assignments and promotion to temporary lieutenant general in October 1943, Simpson took over the Fourth Army at San Jose, California. He moved with it back to Fort Sam Houston in January 1944 and braced for a role in the century’s second European war.

Simpson and his able chief of staff, Brig. Gen. James E. Moore, flew to England on May 6 to organize a new army, the Eighth. Simpson attended the final SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) briefing for the Normandy invasion at St. Paul’s College in London on May 15 and reported to Eisenhower the next day. His former War College classmate told him that his Eighth Army would become the Ninth to avoid confusion with the British Eighth Army of Western Desert fame. Simpson set up a command post at Clifton College in Bristol, Somerset, and began readying the new army for movement to France, where it would join General Bradley’s powerful U.S. 12th Army Group.

The Ninth Army’s headquarters moved to France, became operational at Rennes on September 5, and assumed command of Maj. Gen. Troy H. Middleton’s Eighth Corps, which had been part of the Third Army and was engaged in besieging the French port of Brest. After a full-scale ground and air assault on September 8, followed by 12 days of fierce action, German resistance ceased. The port had been demolished, but it was no longer needed by the Allies. To Simpson, it was a hollow victory.

The Ninth Army moved eastward, and Simpson established his headquarters in Maastricht, Holland, where he built up his command to six divisions in preparation for Operation Queen, a major 12th Army Group effort to cross the Rhine and capture Cologne. Supported by artillery and a strike by 3,000 bombers, the First and Ninth Armies jumped off at noon on November 16. Moving out on a narrow 12-mile front, Simpson’s force encountered fierce resistance, heavy rains, and record flooding as the battle devolved into a 23-day struggle of attrition. The Ninth Army incurred 10,256 casualties while covering only six to 12 miles, but by December 9 it had cleared the western bank of the River Roer. The Ninth had advanced more rapidly than the First.

Although his army had been in action for only three months, Simpson was now well known as the ideal field commander. Quiet spoken, unassuming, and always immaculate, he had a warm smile, was quick witted, and possessed a good sense of humor. He had a knack for making others feel comfortable and enjoyed the confidence of both his officers and enlisted men. He seldom raised his voice, even when rarely angry.

Texas Bill cared about his soldiers’ well-being and had a rule drilled into his subordinate officers: “Never send an infantryman to do a job that an artillery shell can do for him.” He relied heavily on his loyal staff and, unlike many of his peers, was not afraid to delegate responsibility. He let his aides deal with their assigned tasks without checking them at every turn, and, as Field Marshal Sir Archibald P. Wavell said of Field Marshal Edmund Allenby of Palestine fame, did not “devil his staff to death.”

Simpson and Monty: Two Generals Alike

After relocating to the northernmost 12th Army Group sector shortly before the Germans broke through thin American lines in the Ardennes Forest on December 16, 1944, Simpson’s Ninth Army sat out the Battle of the Bulge. It dispatched seven divisions to the threatened area, including Maj. Gen. Robert W. Hasbrouck’s 7th Armored Division, which valiantly defended the town of St.-Vith.

On December 20, Field Marshal Montgomery took command of the northern flank of the Bulge in a bid to “tidy up” the battlefield, and the Ninth Army passed under the operational control of the British 21st Army Group until April 4, 1945, after the encirclement of the Ruhr Valley pocket by the First and Ninth Armies. It was a controversial move because the eccentric, egotistical Monty had rankled many, from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to Eisenhower and Bradley.

But Simpson, a good subordinate who kept himself above politics and personalities, was unfazed. He had told Ike, “You can depend on me to respond cheerfully, promptly, and as efficiently as I possibly can to every instruction he gives.”

Monty was initially politely aloof and skeptical of Simpson’s ability as an Army commander, but the big Texan won him over. He and Moore soon enjoyed a cordial relationship with the wiry, birdlike British officer, whom Simpson admired for his calmness in the Bulge and as an example of military professionalism. Moore described Montgomery as “a feisty little somebody, and he pulled things together down there for First Army during the Battle of the Bulge.”

Simpson and Monty had much in common. Both were energetic, charismatic leaders who kept in close touch with the lower ranks, and both were meticulous planners who strove to keep the battlefield orderly and conserve manpower. What Simpson particularly liked was that Monty left him alone and permitted freedom of action in planning and execution. And he was delighted that his army was built up to 12 full divisions while with the British.

Operation Plunder: The Ninth Army Crosses the Rhine

After crossing the Roer, Simpson pushed his army hard eastward against stiff resistance and then took part in Operation Plunder, the massive assault across the Rhine by Montgomery’s 21st Army Group. He had lined up a quarter of a million men for the biggest operation since D-Day. After an hour-long artillery barrage and 7,500 sorties by Allied planes, the crossings between Rheinberg and Rees got underway at 2 am on Saturday, March 24, 1945. The Ninth Army was on the right and General Sir Miles Dempsey’s British Second Army on the left. Anderson’s U.S. XVI Corps crossed north of the Ruhr.

Prime Minister Churchill and General Eisenhower joined a bevy of war correspondents to watch the crossings. The British leader exulted to Ike, “My dear General, the German is whipped. We’ve got him. He is all through.” Eisenhower, who walked among the assault troops shaking hands and encouraging them, observed, “Simpson performed in his usual outstanding style.” Although fierce fighting followed, Operation Plunder went well, with only 31 casualties. By the end of the day, the Allied bridgehead was more than five miles deep.

Prime Minister Churchill, who had experienced action at Omdurman, in Cuba, in South Africa, and on the Western Front in 1915-1916, was exhilarated to be on the front lines again, and, against Ike’s advice, went across the Rhine on the afternoon of Sunday, March 25. Accompanied by Montgomery, Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and Simpson, he rode a Buffalo amphibious tractor to the outskirts of the occupied town of Wesel. Simpson was nervous about having the three most important British figures of the war so close to the enemy. His concern grew when Churchill, with a cigar clamped in his teeth, dashed forward 40 yards and scrambled onto a destroyed bridge while German shells fell 300 yards downstream.

General Simpson appealed to him. “Prime Minister,” he said, “there are snipers in front of you, they are shelling both sides of the bridge, and now they have started shelling the road behind you. I cannot accept the responsibility for your being here, and must ask you to come away.”

After putting his arms around one of the twisted girders of the bridge for a final time, Churchill quietly withdrew. Sir Alan Brooke reported, “The look on Winston’s face was just like that of a small boy being called away from his sand castles on the beach by his nurse…. It was a sad wrench for him; he was enjoying himself immensely…. However, he came away more obediently than I had expected.” The following day, Alan Brooke watched the prime minister wander off and solemnly urinate into the Rhine as General Patton had done at Oppenheim two days earlier.

“You Must Stop on the Elbe”

The Ninth Army battled on across Germany. The 2nd Armored Division battered through Haltern to the Dortmund-Ems Canal on March 30, beginning what Simpson called “the breathless race” to the strategic Elbe River. On April 1, leading elements of Gillem’s XIII Corps reached the outskirts of Munster while Harmon’s tankers linked up with the First Army’s 3rd Armored Division at Lippstadt, completing the encirclement of the Ruhr.

Three days later, the Ninth Army reverted to the command of the 12th Army Group. Infantry and armor of the XIII and XIX Corps rolled on through crumbling resistance to capture the cities of Hannover, Hildesheim, and Brunswick in quick succession, and on April 11, the 2nd Armored Division raced 52 miles to gain a bridgehead on the River Elbe near Magdeburg. The following day, the 83rd Infantry Division of the 19th Corps and General Gillem’s 5th Armored Division reached the Elbe, followed by the 84th Infantry Division.

By April 15, the XIX and XIII Corps were closed up on the Elbe. Simpson was elated, the Ninth Army’s morale was high, and he reasoned that he could forge on and reach Berlin, 60 miles away. Since his army had advanced 226 miles from the Rhine to the Elbe in 19 days, he was confident that his forces—spearheaded by the 2nd Armored Division—could get to the German capital well before the Soviet Red Army. But Texas Bill’s euphoria was swiftly shattered that Sunday after he was ordered to fly to the 12th Army Group headquarters at Wiesbaden.

“You must stop on the Elbe,” General Bradley told Simpson. “You are not to advance any farther in the direction of Berlin. I’m sorry, Simp, but there it is.” Simpson asked, “Where in the hell did you get this?” Bradley replied, “From Ike.” Simpson was unaware that Ike had decided on March 28 not to go to Berlin, but to link up with the Soviets along the Erfurt-Leipzig-Dresden line.

Simpson was stunned and “heartbroken.” He recalled later, “I got back in the plane in a kind of daze. All I could think of was how am I going to tell my staff, my corps commanders, and my troops? Above all, how am I going to tell my troops?” He insisted then and long after that his army could have reached Berlin in 24 hours. General Gillem said, “Forty-eight hours. That’s all it would have taken.”

The Ninth Army “Performed Magnificently in Europe”

The last few weeks of the European war were an anticlimax for the disappointed Simpson as his army mopped up pockets of enemy resistance, made contact with Soviet troops near Zerbst on April 30, and assumed occupational duties. The war was over for the Ninth Army, much praised by U.S. and British commanders. The army had “performed magnificently in Europe,” said Colonel Jerry D. Morelock, director of the Winston Churchill Memorial and Library at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, later.

Simpson’s forces were transferred to Lt. Gen. Alexander M. Patch’s Seventh Army on June 15, and the gallant Texan returned to America. After being feted in Fort Worth and his Weatherford hometown, he flew to China to serve as deputy to Lt. Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer, the commander of U.S. forces in the China-Burma-India Theater. While arranging for his Ninth Army headquarters to join him, Japan surrendered, so Simpson returned home again.

The Ninth Army was deactivated at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, on October 10, 1945, and Simpson took charge of the Second Army at Memphis, Tennessee, that month. He retained the command until June 1946. Suffering from ulcers and a hernia, he was forced to retire that November 30. He lived in San Antonio, Texas, from December 1947 and was promoted to general on the retired list in July 1954. General Simpson died at the age of 92 in the Brooke Army Hospital on August 15, 1980, and he and his wife were buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Although Simpson’s personal performance during World War II and the combat record of the Ninth Army are often overlooked, they are nevertheless worthy of high praise.

Was it not the ninth that captured the bridge at Remagen?

It was the 9th Armored Division that captured the Remagen Bridge.They were part of Hodge’s First Army.

Good article

No, the bridge at Remagen was captured by elements of the 9th Armored Division of the First Army.