By Duane Schultz

There was a time, in January 1944, when everyone in America had heard of Captain Henry T. Waskow from Belton, Texas. His story had been told by Ernie Pyle, the most revered war correspondent of the day, and it had become the most famous and beloved of all the columns Pyle wrote during World War II. Everyone who read a newspaper or magazine or listened to the radio knew about the 25-year-old captain and how his men mourned his passing. It moved the national conscience, capturing the attention of the American public to a degree that few stories ever had.

In the nation’s capital, The Washington Daily News put Ernie Pyle’s column on its front page, and all but 39 copies sold out in a day, an unheard of achievement. The editor of Waskow’s hometown paper wrote, “If it doesn’t touch you, your heart’s a little cold.” Time magazine reprinted the column about Waskow’s death, and two leading radio personalities, Arthur Godfrey and Raymond Gram Swing, read it on the air. Even the most hardened listeners were moved to tears.

“In this war,” Ernie Pyle wrote, “I have known a lot of officers who were loved and respected by the soldiers under them. But never have I crossed the trail of any man as beloved as Captain Henry T. Waskow.” One soldier in B Company said that he never knew the captain to do anything unfair to the troops under his command. Another remembered, “He never gave an order. He asked his men to follow him and they did and they all loved him.”

Lieutenant Ray Hood said simply, “His men would die for him.” Riley Tidwell, Waskow’s runner, who was 20 years old when Waskow was killed, described the 25-year-old captain as being “just like my Dad, or even better to me than my Dad.” A sergeant said, “After my father, he came next.”

The Moment Captain Waskow Died

Tidwell was with Waskow when he was killed. A few hours before, Tidwell had made coffee and toast for him by spearing a piece of bread on a bent coat hanger and holding it over a can of Sterno. Waskow really liked his coffee and toast, and one of the last things he said to Tidwell was, “When we get back to the States, I’m going to get one of those smart-aleck toasters where you put the bread in and it pops up.”

When he finished eating, they headed up the hill. Suddenly, they heard an incoming German shell. Waskow shoved Tidwell out of the way and yelled, “Hit the ground!”

“I did,” Tidwell recalled. “I hit the ground and the First Sergeant with me, he hit the ground, but the Captain didn’t make it. A piece of shrapnel caught him in the chest. It killed him right there.” It was December 14, 1943, on Monte Sammucro, not far from the shattered town of San Pietro, Italy.

Tidwell did not want to leave Captain Waskow’s body, but the battalion commander ordered him to get treatment for his trench foot. Tidwell sought shelter in a small wooden shack at the base of the mountain to try to get warm. There he saw a group of soldiers sitting with a man who was writing on a notepad. A fuzzy woolen cap was perched on his head. “I found out his name was Ernie Pyle, the correspondent. We sat and talked for a long time and I told him about my captain.”

“God Damn it to Hell Anyway”

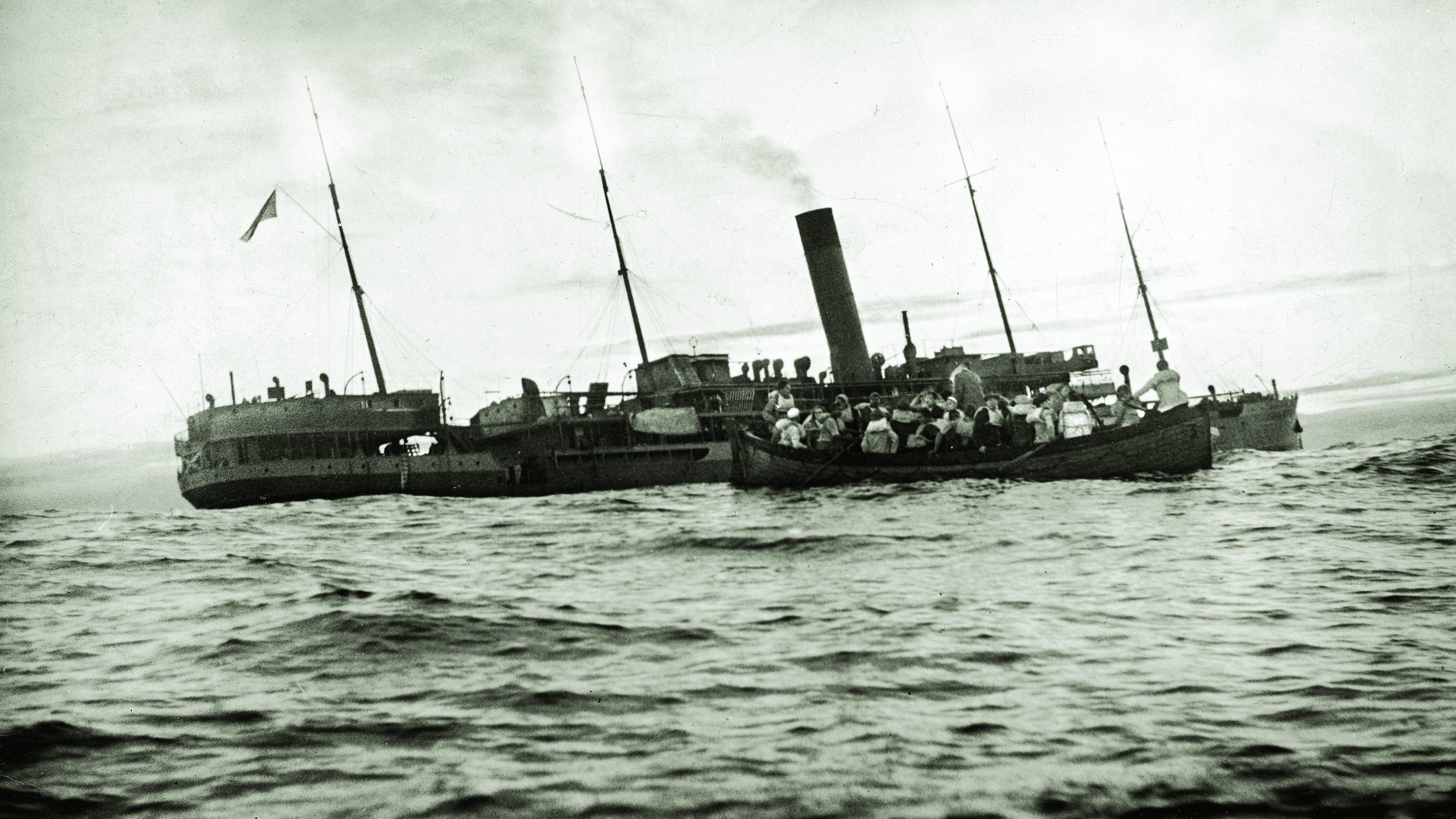

The next night, Ernie Pyle watched as five bodies were brought down the mountain strapped to the backs of mules. They were draped over the wooden saddles, heads down, legs dangling stiffly over the other side. The procession halted at the bottom of the hill, and the dead soldiers were untied and lifted off the mules. For an awkward moment, each body was held upright, as if the man was standing, until the detail could tighten their grip on the body and place it down gently on the muddy road beside a stone wall. A group of soldiers approached the bodies.

“This one is Captain Waskow,” one man said, gesturing to the first corpse. The others looked on silently. No one moved. No one spoke as they stared at the body of their company commander who had meant so much to them. “The men in the road seemed reluctant to leave,” Pyle wrote. “They stood around, and gradually I could sense them moving closer to Captain Waskow’s body. Not so much to look, I think, as to say something in finality to him and to themselves.

“One soldier came and looked down, and said aloud, ‘Goddamn it.’ That’s all he said, and then he walked away. Another one came. He said, ‘God damn it to hell anyway.’ He looked down for a few last moments, and then he turned and left.

“Then another man came; I think he was an officer. It was hard to tell officers from men in the half light, for they all were bearded and grimy dirty. The man looked down into the dead captain’s face, and spoke directly to him. He said: ‘I sure am sorry, old man.’

“Then a soldier came and stood beside the officer, and bent over, and he too spoke to his dead captain, not in a whisper, but awfully tenderly, and he said ‘I sure am sorry, sir.’

“Then the first man squatted down, and he reached down and took the dead hand, and he sat there for a full five minutes, holding the dead hand in his own and looking intently into the dead face, and he never uttered a sound all the time he sat there.

“And finally he put his hand down, and then reached up and gently straightened the points of the captain’s shirt collar, and then he sort of rearranged the tattered edges of his uniform around the wound. And then he got up and walked away down the road in the moonlight, all alone.”

An Unlikely Hero

Henry Waskow was an unlikely hero. He had been a quiet, serious, sober boy, the kind of kid who always did his schoolwork on time and tried not to make trouble for his parents or anyone else. His classmates remembered him as “a sweet little oddball.” One said, “He was never young, not in a crazy high-school kid way.”

He recognized that he was different from the other children, and he mentioned that in his “just in case” letter to be sent to his parents if he was killed in combat. “I guess I have always appeared strange at times; it was because I had weighty responsibilities that preyed on my mind and wouldn’t let me slack up to be human, like I so wanted to be. I felt so unworthy at times of the great trust my country had put in me that I simply had to keep plugging to satisfy my own self that I was worthy of that trust. I have not, at the time of writing this, done that, and I suppose I never will.”

Waskow was one of eight children of German Baptist cotton farmers. He was short and scrawny and wore the same striped overalls and blue shirt to school every day. He worked hard, was elected president of the senior class, and won second prize in a statewide public speaking contest. He graduated with the highest grades anyone had earned in 20 years. He even led the algebra class for a week when the teacher became ill.

A classmate recalled in 2010 that many of the girls at school were attracted to Waskow, but he did not have time for them. “He had a life to live,” she said, “goals to accomplish. Henry did what he was supposed to do because he was supposed to do it.” He did not smoke or drink and remained very much an introvert.

Waskow attended a local junior college for two years and then enrolled at Trinity College in San Antonio, working his way through school as a campus janitor. He joined the Texas National Guard because he needed the $1 he was paid for every drill session he attended. When the Guard was called to active duty in 1940 as the 36th Division, Waskow advanced quickly to the rank of captain. And just as quickly he became idolized by his men, some of whom were older than he was.

Waskow was killed on December 14, but his family in Texas was not notified until December 29. The War Department, in an effort to avoid dampening the holiday spirit, deliberately held up those dreaded telegrams announcing more deaths until after the Christmas holiday. Waskow’s mother had a premonition, and when the telegram finally arrived she simply said, “I was right, wasn’t I? Henry’s gone.” She died six weeks later.

“Ernie Pyle’s Movie”

Ernie Pyle was overwhelmed by the response to his column, which appeared on January 10, 1944. He had been suffering from exhaustion and anemia due to the long stint at the front and was also depressed, drinking too much and convinced he was finished as a writer. He believed that all his best work was behind him and that he would never write anything good again. Yet, in that same year Ernie Pyle was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished work as a frontline war correspondent. Many of his columns, including the one about Captain Waskow, were collected in a popular book, Here Is Your War. On April 18, 1945, Pyle was killed by Japanese machine-gun fire on the island of Ie Shima, 10 miles west of Okinawa.

Two months to the day after Pyle died, a movie had its gala premiere in New York City. Some people called it “Ernie Pyle’s movie” because so much of it was drawn from his columns. The Story of G.I. Joe opened to rave reviews, and audiences across the nation flocked to see it. Soldiers who had been in combat said it was the most realistic depiction they had ever seen of life at the front.

The closing scene was taken from Pyle’s most popular column. The only change was that the words “Goddamn it” had to be omitted, considered by the censors of the day to be profanity. The soldiers in the film, with the Ernie Pyle character observing them, stood by Captain Waskow’s body to say their farewells. One man knelt to straighten his collar and stayed quietly for a while, exactly as Pyle had described.

Ernie Pyle had spent two weeks in Hollywood “nosing into the picture” as he put it. “I did not like the title,” he wrote, “but nobody could think of a better one, and I was too lazy to try.” Actor Burgess Meredith played Pyle. “The makeup men shaved his head,” Pyle wrote in a column on February 14, 1945, “and wrinkled his face and made him up so well that he’s even uglier than I am, poor fellow.”

Robert Mitchum, then a relatively unknown actor, played Captain Waskow, but the name was changed to “Walker” in the movie to make it sound more ethnically neutral, more “American.” Army brass had insisted on the change. Reviewers called The Story of G.I. Joe a “hard-hitting, penetrating drama,” with “uncompromising realism.” They said it had “tremendous emotional impact” and was “humorous, poignant, and tragic.”

Chosen for the National Film Registry

In 2009 the film became one of 25 selected for addition to the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress, judged to be culturally, historically, and aesthetically important enough to be preserved for all time. In 2012, David Denby, film critic for The New Yorker, called it “probably the grimmest and most poetic” of all World War II films, “beautifully photographed,” possessing a mood that is “somber, slightly maddened, fatalistic.”

Captain Henry Thomas Waskow, U.S. Army Serial No. 0-407112, is buried in Grave 33, Row 6, Plot G, in the Rome-Sicily American Cemetery and Memorial. The cemetery is located outside the town of Nettuno, a few miles east of Anzio and 38 miles south of Rome. It contains 7,860 graves; the names of 3,095 American soldiers missing in action are engraved on the white marble walls of the chapel.

Ernesto Rosi has worked at the cemetery since 1979. In an interview in 2012, he said that Waskow’s grave remains “one of the most visited gravesites in our cemetery.” He often recounts Captain Waskow’s story for visitors, and when he does, they all want to see the resting place of the soldier Ernie Pyle made famous.

“If you get to read this,” Captain Waskow wrote in his final letter home, “I will have died defending my country and all that it stands for, the most honorable and distinguished death a man can die. I made my choice, dear ones. I volunteered in the Armed Forces because I thought that I might be able to help this great country of ours in its hours of darkness and need—the country that means more to me than life itself. If I have done that, then I can rest in peace, for I will have done my share to make the world a better place in which to live.”

Duane Schultz is a psychologist who has written a dozen military history books including Into the Fire: The Most Fateful Mission of World War II and Crossing the Rapido: A Tragedy of World War II. His most recent book is The Fate of War: Fredericksburg, 1862. He is currently working on a book on the Marine Raiders of World War II.

I like the article’s

Keep it up

Appreciate Captain Waskow’s service and sacrifice. Am also grateful to know there are other Captain Waskows in this world.